Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a peace treaty signed on March 3, 1918, between the new Bolshevik government of Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russia's participation in World War I. The treaty was signed at German-controlled Brest-Litovsk (Polish: Brześć Litewski; since 1945, Brest, nowadays in Belarus), after two months of negotiations. The treaty was agreed upon by the Russians to stop further invasion. According to the treaty, Soviet Russia defaulted on all of Imperial Russia's commitments to the Allies and eleven nations became independent in Eastern Europe and western Asia.

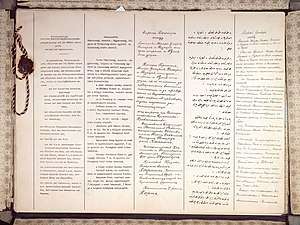

The first two pages of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in (from left to right) German, Hungarian, Bulgarian, Ottoman Turkish and Russian | |

| Signed | 3 March 1918 (during the First World War) |

|---|---|

| Location | Brest-Litovsk, Ukrainian People's Republic[1] |

| Condition | Ratification |

| Signatories |

|

| Languages | |

In the treaty, Russia ceded hegemony over the Baltic states to Germany; they were meant to become German vassal states under German princelings.[2] Russia also ceded its province of Kars Oblast in the South Caucasus to the Ottoman Empire and recognized the independence of Ukraine. According to historian Spencer Tucker, "The German General Staff had formulated extraordinarily harsh terms that shocked even the German negotiator."[3] Congress Poland was not mentioned in the treaty, as Germans refused to recognize the existence of any Polish representatives, which in turn led to Polish protests.[4] When Germans later complained that the later Treaty of Versailles in the West of 1919 was too harsh on them, the Allied Powers responded that it was more benign than the terms imposed by the Brest-Litovsk treaty.[5]

The treaty was annulled by the Armistice of 11 November 1918,[6] when Germany surrendered to the western Allies. However, in the meantime it did provide some relief to the Bolsheviks, already fighting the Russian Civil War (1917–1922) following the Russian Revolutions of 1917, by the renunciation of Russia's claims on modern-day Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Ukraine and Lithuania.

It is considered the first diplomatic treaty ever filmed.[7]

Background

By 1917, Germany and Imperial Russia were stuck in a stalemate on the Eastern Front of World War I and the Russian economy had nearly collapsed under the strain of the war effort. The large numbers of war casualties and persistent food shortages in the major urban centers brought about civil unrest, known as the February Revolution, that forced Emperor (Tsar/Czar) Nicholas II to abdicate. The Russian Provisional Government that replaced the Tsar in early 1917 continued the war. Foreign Minister Pavel Milyukov sent the Entente Powers a telegram, known as Milyukov note, affirming to them that the Provisional Government would continue the war with the same war aims that the former Russian Empire had. The pro-war Provisional Government was opposed by the self-proclaimed Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, dominated by leftist parties. Its Order No. 1 called for an overriding mandate to soldier committees rather than army officers. The Soviet started to form its own paramilitary power, the Red Guards, in March 1917.[8]

The continuing war led the German Government to agree to a suggestion that they should favor the opposition Communist Party (Bolsheviks), who were proponents of Russia's withdrawal from the war. Therefore, in April 1917, Germany transported Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin and thirty-one supporters in a sealed train from exile in Switzerland to Finland Station, Petrograd.[9] Upon his arrival in Petrograd, Lenin proclaimed his April Theses, which included a call for turning all political power over to workers' and soldiers' soviets (councils) and an immediate withdrawal of Russia from the war. At around the same time, the United States entered the war, potentially shifting the balance of the war against the Central Powers. Throughout 1917, Bolsheviks called for the overthrow of the Provisional Government and an end to the war. Following the disastrous failure of the Kerensky Offensive, discipline in the Russian army deteriorated completely. Soldiers would disobey orders, often under the influence of Bolshevik agitation, and set up soldiers' committees to take control of their units after deposing the officers.

The defeat and ongoing hardships of war led to anti-government riots in Petrograd, the "July Days" of 1917. Several months later, on 7 November (25 October old style), Red Guards seized the Winter Palace and arrested the Provisional Government in what is known as the October Revolution.

A top priority of the newly established Soviet government was to end the war. On 8 November 1917 (26 October 1917 O.S) Vladimir Lenin signed the Decree on Peace, which was approved by the Second Congress of the Soviet of Workers', Soldiers', and Peasants' Deputies. The Decree called "upon all the belligerent nations and their governments to start immediate negotiations for peace" and proposed an immediate withdrawal of Russia from World War I. Leon Trotsky was appointed Commissar of Foreign Affairs in the new Bolshevik government. In preparation for peace talks with the representatives of the German government and the representatives of the other Central Powers, Leon Trotsky appointed his good friend Adolph Joffe to represent the Bolsheviks at the peace conference.

Peace negotiations

On 15 December 1917, an armistice between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers was concluded. On 22 December, peace negotiations began in Brest-Litovsk.

Arrangements for the conference were the responsibility of General Max Hoffmann, chief of staff of the Central Powers' forces on their Eastern Front (Oberkommando-Ostfront). The delegations that had negotiated the armistice were made stronger. Prominent additions on the Central Powers’ side were the foreign ministers of Germany Richard von Kühlmann and of Austria-Hungary Count Ottokar Czernin, both the Ottoman grand vizier Talaat Pasha and Foreign Minister Nassimy Bey. The Bulgarians were headed by Minister of Justice Popoff, who was later joined by Prime Minister Vasil Radoslavov.[10][11]

The Soviet delegation was led by Adolph Joffe who had already led their armistice negotiators, but his group was made more cohesive by eliminating most of the representatives of social groups, like peasants and sailors, and the addition of tsarist general Aleksandr Samoilo and the noted Marxist historian Mikhail Pokrovsky. It still included Anastasia Bitsenko, a former assassin, representing the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries who were at odds with the Bolsheviks. Again the negotiators met in the fortress in Brest Litovsk, while the delegates were housed in temporary wooden structure in its courtyards, because the city had been burnt to the ground in 1915 by the retreating Russian army. They were cordially welcomed by the commander of the Eastern Front, Prince Leopold of Bavaria, who sat with Joffe on the head table at the opening banquet with one hundred guests.[12] As they had during the armistice negotiations both sides continued to eat dinner and supper together amicably intermingled in the officers' mess.

When the conference convened Kühlmann asked Joffe to present the Russian conditions for peace. He made six points, all variations of the Bolshevik slogan of peace with "no annexations or indemnities". The Central Powers accepted these principles "but only in case all belligerents [including the nations of the Entente] without exception pledge themselves to do the same".[13] They did not intend to annex territories occupied by force. Joffe telegraphed this marvelous news to Petrograd. Thanks to informal chatting in the mess, one of Hoffmann's aides, Colonel Friedrich Brinckmann, realized that the Russians had optimistically misinterpreted the Central Power's meaning.[14] It fell to Hoffmann to set matters straight at dinner on 27 December: Poland, Lithuania and Courland, already occupied by the Central Powers, were determined to separate from Russia, on the principle of self-determination that the Bolsheviks themselves espoused. Joffe "looked as if he had received a blow on the head".[15] Pokrovsky wept as he asked how they could speak of "peace without annexations when Germany was tearing eighteen provinces away from the Russian state".[16] The Germans and Austro-Hungarian planned to annex slices of Polish territory and to set up a rump Polish state with what remained, while the Baltic provinces were to become client states ruled by German princes. Czernin was beside himself with this hitch that was slowing the negotiations; self-determination was anathema to his government and they urgently needed grain from the east because Vienna was on the verge of starvation. He proposed to make a separate peace.[17] Kühlmann warned that if they negotiated separately Germany would immediately withdraw all its divisions from the Austrian front; Czernin dropped that threat. The food crisis in Vienna was eventually eased by "forced drafts of grain from Hungary, Poland, and Romania and by a last moment contribution from Germany of 450 truck-loads of flour".[18] At the Russian request they agreed to recess the talks for twelve days.

The Soviets' only hopes were that given time their allies would agree to join the negotiations or that the western European proletariat would revolt, so their best strategy was to prolong the negotiations. As Foreign Minister Leon Trotsky wrote, "To delay negotiations, there must be someone to do the delaying".[19] Therefore Trotsky replaced Joffe as the leader.

On the other side there were significant political realignments. On New Year's Day in Berlin the Kaiser insisted that Hoffmann reveal his views on the future German-Polish border. He advocated taking a small slice of Poland; Hindenburg and Ludendorff wanted much more. They were furious with Hoffmann for breaching the chain of command and wanted him dismissed and sent to command a division. The Kaiser refused, but Ludendorff no longer spoke with Hoffmann on the telephone, now communication was through an intermediary.[20] The German Supreme Commanders were also furious at ruling out of annexations, contending that the peace "must increase Germany's material power".[21] They denigrated Kühlmann and pressed for additional territorial acquisitions. When Hindenburg was asked why they needed the Baltic states he replied, "To secure my left flank for when the next war happens."[22] However, the most profound transformation was that a delegation from the Ukrainian Rada, which had declared independence from Russia, had arrived at Brest-Litovsk. They would make peace if they were given the Polish city of Cholm and its surroundings, and then would provide desperately needed grain. Czernin no longer was desperate for a prompt settlement with the Russians.

When they reconvened Trotsky declined the invitation to meet Prince Leopold and terminated shared meals and other sociable interactions with the representatives of the Central Powers. Day after day Trotsky "engaged Kühlmann in debate, rising to subtle discussion of first principles that ranged far beyond the concrete territorial issues that divided them".[23] The Central Powers signed a peace treaty with Ukraine during the night of 8–9 February, even though the Russians had retaken Kiev. German and Austro-Hungarian troops entered Ukraine to prop up the Rada. Finally Hoffmann broke the impasse with the Russians by focusing the discussion on maps of the future boundaries. Trotsky summarized their situation "Germany and Austria-Hungary are cutting off from the domains of the former Russian Empire territories more than 150,000 square kilometers in size."[24] He was granted a nine day recess for the Russians to decide whether to sign.

.jpg)

In Petrograd, Trotsky argued passionately against signing, proposing that instead "they should announce the termination of the war and demobilization without signing any peace."[25] Lenin was for signing rather than having an even more ruinous treaty forced on them after a few more weeks of military humiliation. The "Left Communists", led by Nikolai Bukharin and Karl Radek, were sure that Germany, Austria, Turkey, and Bulgaria were all on the verge of revolution. They wanted to continue the war with a newly-raised revolutionary force while awaiting for these upheavals.[26] Consequently Lenin agreed to Trotsky's formula—a position summed up as "no war – no peace"—which was announced when the negotiators reconvened on 10 February 1918. The Soviets thought their stalling was succeeding until 16 February when Hoffmann notified them that the war would resume in two days, when fifty-three divisions advanced against the near-empty Soviet trenches. On the night of 18 February the Central Committee supported Lenin's resolution that they sign the treaty by a margin of seven to five. Hoffmann kept advancing until 23 February when he presented new terms that included the withdrawal of all Soviet troops from Ukraine and Finland. They were given 48 hours to decide. Lenin told the Central Committee that "you must sign this shameful peace in order to save the world revolution".[27] If they did not agree he would resign. He was supported by six Central Committee members, opposed by three, with Trotsky and three others abstaining.[28] Trotsky resigned as foreign minister and was replaced by Georgy Chicherin.

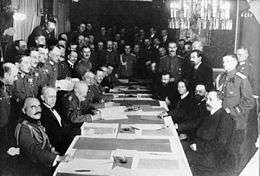

When Sokolnikov arrived at Brest-Litovsk he declared "we are going to sign immediately the treaty presented to us as an ultimatum but at the same time refuse to enter into any discussion of its terms".[29] The treaty was signed at 17:50 on 3 March 1918.

Terms of the treaty

Signing

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed on 3 March 1918. The signatories were Soviet Russia signed by Grigori Sokolnikov on the one side and the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and Ottoman Empire on the other.

The treaty marked Russia's final withdrawal from World War I as an enemy of her co-signatories, on severe terms. In all, the treaty took away territory that included a quarter of the population and industry of the former Russian Empire [30] and nine-tenths of its coal mines.[31]

Territorial cessions in eastern Europe

Russia renounced all territorial claims in Finland (which it had already acknowledged), Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), most of Belarus, and Ukraine.

The territory of the Kingdom of Poland was not mentioned in the treaty, because Russian Poland had been a possession of the white movement, not the Bolsheviks. The treaty stated that "Germany and Austria-Hungary intend to determine the future fate of these territories in agreement with their populations." Most of these territories were in effect ceded to Germany, which intended to have them become economic and political dependencies. The many ethnic German residents (volksdeutsch) would be the ruling elite. New monarchies were created in Lithuania and the United Baltic Duchy (which comprised the modern countries of Latvia and Estonia). The German aristocrats Wilhelm Karl, Duke of Urach (in Lithuania), and Adolf Friedrich, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (in the United Baltic Duchy), were appointed as rulers.

This plan was detailed by German Colonel General Erich Ludendorff, who wrote, "German prestige demands that we should hold a strong protecting hand, not only over German citizens, but over all Germans."[32]

The occupation of Western Russia ultimately proved a costly blunder for Berlin as over one million German troops lay sprawled out from Poland nearly to the Caspian Sea, all idle and depriving Germany of badly needed manpower in France. The hopes of utilizing Ukraine's grain and coal proved abortive and in addition, the local population became increasingly upset at the occupation. Revolts and guerrilla warfare began breaking out all over the occupied territory, many of them inspired by Bolshevik agents. German troops also had to intervene in the Finnish Civil War, and Ludendorff became increasingly paranoid about his troops being affected by propaganda emanating from Moscow; this was one of the reasons he was reluctant to transfer divisions to the Western Front. The attempt at establishing an independent Ukrainian state under German guidance was unsuccessful as well. Despite all this, Ludendorff completely ruled out the idea of marching on Moscow and Petrograd to remove the Bolshevik government from power.

Germany transferred hundreds of thousands of veteran troops to the Western Front for the 1918 Spring Offensive, which shocked the Allied Powers, but ultimately failed. Some Germans later blamed the occupation for significantly weakening the Spring Offensive.

Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine became independent, while Bessarabia united with Romania.

Russia lost 34% of its population, 54% of its industrial land, 89% of its coalfields, and 26% of its railways. Russia was also fined 300 million gold marks.

Territorial cessions in the Caucasus

At the insistence of Talaat Pasha, the treaty declared that the territory Russia took from the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), specifically Ardahan, Kars, and Batumi, were to be returned. At the time of the treaty, this territory was under the effective control of Armenian and Georgian forces.

Paragraph 3 of Article IV of the treaty stated that:

The districts of Erdehan, Kars, and Batum will likewise and without delay be cleared of Russian troops. Russia will not interfere in the reorganization of the national and international relations of these districts, but leave it to the population of these districts to carry out this reorganization in agreement with the neighboring States, especially with the Ottoman Empire.

Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia rejected the treaty and instead declared independence. They formed the short-lived Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic.

Soviet-German financial agreement of August 1918

In the wake of Soviet repudiation of Tsarist bonds, nationalisation of foreign-owned property and confiscation of foreign assets, the Soviets and Germany signed an additional agreement on 27 August 1918. The Soviets agreed to pay six billion marks in compensation for German losses.

ARTICLE 2 Russia shall pay Germany six billion marks as compensation for losses sustained by Germans through Russian measures; at the same time corresponding claims on Russia's part are taken into account, and the value of supplies confiscated in Russia by German military forces after the conclusion of peace is taken into account.[33]

Lasting effects

The treaty meant that Russia now was helping Germany win the war by freeing up a million German soldiers for the Western Front[34] and by "relinquishing much of Russia's food supply, industrial base, fuel supplies, and communications with Western Europe".[35][36] According to historian Spencer Tucker, the Allied Powers felt that "The treaty was the ultimate betrayal of the Allied cause and sowed the seeds for the Cold War. With Brest-Litovsk, the spectre of German domination in Eastern Europe threatened to become reality, and the Allies now began to think seriously about military intervention [in Russia]."[37]

Immediately after the signing of the treaty, Lenin moved the Soviet government from Petrograd to Moscow.[38] Trotsky blamed the peace treaty on the bourgeoisie, the social revolutionaries,[39] Tsarist diplomats, Tsarist bureaucrats, "the Kerenskys, Tseretelis and Chernovs"[40] the Tsarist regime, and the "petty-bourgeois compromisers".[41]

Relations between Russia and the Central Powers did not go smoothly. The Ottoman Empire broke the treaty by invading the newly created First Republic of Armenia in May 1918. Joffe became the Soviet ambassador to Germany. His priority was distributing propaganda to trigger the German revolution. On 4 November 1918 "the Soviet courier's packing-case had 'come to pieces'" in a Berlin railway station;[42] it was filled with insurrectionary documents. Joffe and his staff were ejected from Germany in a sealed train on 5 November 1918. In the Armistice of 11 November 1918 that ended World War I, one clause abrogated the Brest-Litovsk treaty. Next the Bolshevik legislature (VTsIK) annulled the treaty on 13 November 1918, and the text of the VTsIK Decision was printed in Pravda newspaper the next day. In the year after the armistice following a timetable set by the victors the German Army withdrew its occupying forces from the lands gained in Brest-Litovsk. The fate of the region, and the location of the eventual western border of the Soviet Union, was settled in violent and chaotic struggles over the course of the next three and a half years. The Polish–Soviet War was particularly bitter; it ended with the Treaty of Riga in 1921. Although most of Ukraine fell under Bolshevik control and eventually became one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union, Poland and the Baltic states re-emerged as independent nations. In the Treaty of Rapallo, concluded in April 1922, Germany accepted the Treaty's nullification, and the two powers agreed to abandon all war-related territorial and financial claims against each other. This state of affairs lasted until 1939. As a consequence of the Germans breaking the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union advanced its borders westward in response to the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 and taking a small part of Finland in November 1939 and annexing the Baltic States, and Romania (Bessarabia) in 1940. It thus overturned almost all the territorial losses incurred at Brest-Litovsk, except for the main part of Finland, western Congress Poland, and western Armenia.

The treaty marked a significant contraction of the territory controlled by the Bolsheviks or that they could lay claim to as effective successors of the Russian Empire. While the independence of Finland and Poland was already accepted by them in principle, the loss of Ukraine and the Baltics created, from the Bolshevik perspective, dangerous bases of anti-Bolshevik military activity in the subsequent Russian Civil War (1918–1922). However, Bolshevik control of Ukraine and Transcaucasia was at the time fragile or non existent.[43] Many Russian nationalists and some revolutionaries were furious at the Bolsheviks' acceptance of the treaty and joined forces to fight them. Non-Russians who inhabited the lands lost by Bolshevik Russia in the treaty saw the changes as an opportunity to set up independent states.

For the Western Allied Powers, the terms that Germany had imposed on Russia were interpreted as a warning of what to expect if the Central Powers won the war. Between Brest-Litovsk and the point when the situation in the Western Front became dire, some officials in the German government and the high command began to favor offering more lenient terms to the Allied Powers in exchange for their recognition of German gains in the east.

Portraits

Emil Orlik, the Viennese Secessionist artist, attended the conference, at the invitation of Richard von Kühlmann. He drew portraits of all the participants, along with a series of smaller caricatures. These were gathered together into a book, Brest-Litovsk, a copy of which was given to each of the participants.[44]

See also

References

- (in Ukrainian) To whom did Brest belong in 1918? Argument among Ukraine, Belarus, and Germany. Ukrayinska Pravda, 25 March 2011.

- Kann, Robert A. (1974). A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 479–480. ISBN 0-520-02408-7.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2005). World War One. ABC-CLIO. p. 225.

- Seegel, Steven (2012). Mapping Europe's Borderlands: Russian Cartography in the Age of Empire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-226-74425-4.

At Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, no Polish delegation was invited to the negotiations, and in the Polish press, journalists condemned it as yet another partition of the lands east of the Bug River by great powers.

- Steiner, Zara S. (2005). The Lights that Failed: European International History, 1919–1933. Oxford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-19-822114-2.

- Fry, Michael Graham; Goldstein, Erik; Langhorne, Richard (2002). Guide to International Relations and Diplomacy. Continuum. p. 188. ISBN 0-8264-5250-7.

- Stone, N. (2009). World War One : A Short History. New York: Basic Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-465-01368-5.

- Borislav Chernev, Twilight of Empire: The Brest-Litovsk Conference and the Remaking of East-Central Europe, 1917-1918 (2019) pp 3-38.

- Wheeler-Bennett, John W. (1938). Brest-Litovsk : The forgotten peace. London: Macmillan. pp. 36–41.

- Wheeler-Bennett, John W. (1938). Brest-Litovsk : The Forgotten Peace, March 1918. London: Macmillan. pp. 111–112.

- Lincoln, W. B. (1986). Passage through Armageddon : The Russians in War & Revolution 1914–1918. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 489–491. ISBN 0-671-55709-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Czernin, Count Ottokar (1919). In the world war. London: Cassall. p. 228.

- Lincoln 1986, p. 490.

- Wheeler-Bennett, 1938, p. 124.

- Hoffmann, Major General Max (1929). War Diaries and other papers. 1. London: Martin Secker. p. 209.

- Lincoln 1986, p. 401

- Lincoln 1986, p. 491

- Wheeler-Bennett, 1938, p. 170.

- Trotsky, Leon (1930). "My Life" (PDF). Marxists. Charles Schribner’s Sons. p. 286.

- Wheeler-Bennett 1938, pp. 130–136.

- Ludendorff, General (1920). The General Staff and its problems The history of the relations between the high command and the German Imperial Government as revealed in official documents. 2. London: Hutchinson. p. 209.

- David Stevenson (2009). Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. Basic Books. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-7867-3885-4.

- Lincoln 1986, p. 494

- Lincoln 1986, p. 496

- Wheeler-Bennett, John W. (1938). Brest-Litovsk : The Forgotten Peace, March 1918. London: Macmillan. pp. 185–186.

- Fischer, Ruth (1982) [1948]. Stalin and German Communism: A Study on the Origins of the State Party. New Brunswick NJ: Transition Books. p. 39. ISBN 0-87855-880-2.

- Wheeler-Bennett, 1938, p. 260.

- Fischer, 1982, pp. 32–36.

- Wheeler-Bennett, 1938, pp. 268–269.

- John Keegan, The First World War (New York: Vintage Books, 2000), p. 342.

- Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, 1960, p. 57

- Ludendorff, Erich von (1920). The General Staff and its Problems. London. p. 562.

- Russian-German Financial Agreement, August 27, 1918. (Izvestia, September 4, 1918.)

- Jerald A Combs (2015). The History of American Foreign Policy from 1895. Routledge. p. 97.

- Todd Chretien (2017). Eyewitnesses to the Russian Revolution. p. 129.

- Michael Senior (2016). Victory on the Western Front: The Development of the British Army 1914–1918. p. 176.

- Spencer C. Tucker (2013). The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. p. 608.

- "LENINE'S [sic] MIGRATION A QUEER SCENE", The New York Times, March 16, 1918

- The Military Writings of Leon Trotsky Volume 1, 1918 TWO ROADS "We have not forgotten, in the first place, that the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk meant the noose that was flung about our neck by the bourgeoisie and the SRs who were responsible for the offensive of June 18."

- The Military Writings of Leon Trotsky Volume 1, 1918 THE INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL TASKS OF THE SOVIET POWER "Those who bear the guilt of the Brest-Litovsk peace are the Tsarist bureaucrats and diplomats who involved us in the dreadful war, squandering what the people had accumulated, robbing the people – they who kept the working masses in ignorance and slavery. On the other hand, no less guilt rests with the compromisers, the Kerenskys, Tseretelis and Chernovs."

- The Military Writings of Leon Trotsky Volume 1, 1918 WE NEED AN ARMY "the entire burden of recent events, above all, the Brest peace, has fallen tragically upon us only through the previous management of affairs by the Tsarist regime and, following it, by the regime of the petty-bourgeois compromisers".

- Wheeller-Bennett, 1938, p. 359.

- Keegan, John (1999) [1998]. The First World War. London: Pimlico. p. 410. ISBN 0-7126-6645-1.

- Jewish Museum in Prague (2013–2015). Emil Orlik (1870–1932) – Portraits of Friends and Contemporaries [description of exhibition in 2004]. Retrieved 2015-04-03.

Further reading

- Chernev, Borislav (2017). Twilight of Empire: The Brest-Litovsk Conference and the Remaking of East-Central Europe, 1917–1918. U of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-0149-5, a major scholarly history. excerpt; also online review

- Dornik, Wolfram; Lieb, Peter (2013). "Misconceived realpolitik in a failing state: the political and economical fiasco of the Central Powers in the Ukraine, 1918". First World War Studies. 4 (1): 111–124. doi:10.1080/19475020.2012.761393.

- Freund, Gerald (1957). Unholy Alliance: Russian-German Relations from the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk to the Treaty of Berlin. New York: Harcourt. OCLC 1337934.

- Kennan, George (1960). Soviet Foreign Policy 1917–1941. Van Nostrand. OCLC 405941.

- Kettle, Michael (1981). Allies and the Russian Collapse. London: Deutsch. ISBN 0-233-97078-9.

- Magnes, Judah Leon (2010). Russia and Germany at Brest-Litovsk : a Documentary History of the Peace. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-171-68826-6, primary sources.

- Wheeler-Bennett, John (1938). Brest-Litovsk : The Forgotten Peace, March 1918, older scholarly history.

External links

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (Yale University Avalon Project), including links to appendices.

- Resolution of the Fourth All-Russian (Extraordinary) Soviet Congress Ratifying the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

- Map of Europe after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, at omniatlas.com.

- Susanne Schattenberg: Brest-Litovsk, Treaty of, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.