Johor Bahru

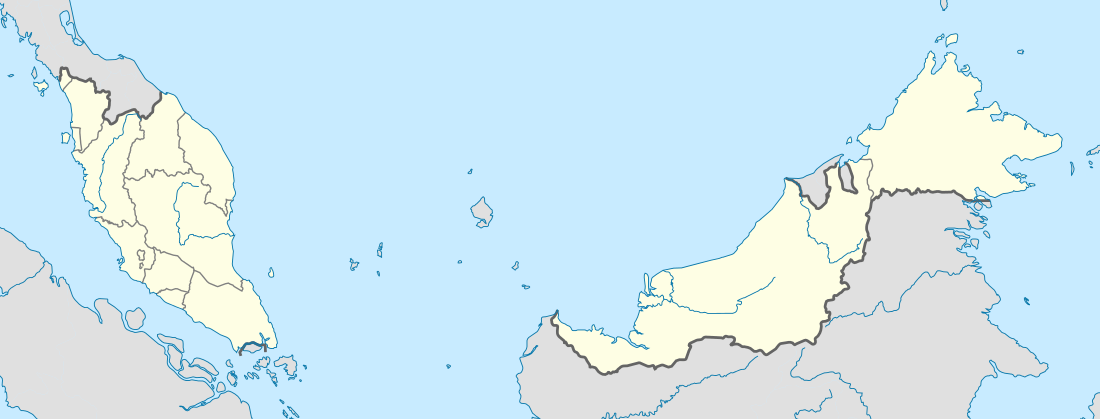

Johor Bahru (Malaysian pronunciation: [ˈdʒohor ˈbahru]) is the capital of the state of Johor, Malaysia. It is located along the Straits of Johor at the southern end of Peninsular Malaysia. The city has a population of 663,307 within an area of 220 km2. Johor Bahru is adjacent to the city of Iskandar Puteri, both anchoring Malaysia's third largest urban agglomeration, Iskandar Malaysia, with a population of 1,638,219.[4][5]

Johor Bahru | |

|---|---|

City and state capital | |

| City of Johor Bahru Bandaraya Johor Bahru | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Jawi | جوهر بهرو |

| • Chinese | 新山 |

| • Tamil | ஜொஹோர் பாரு |

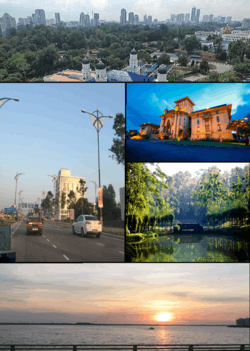

Clockwise from top: Johor Bahru city centre, Sultan Ibrahim Building, City Rainforest, Straits of Johor view from top of the Johor–Singapore Causeway and city street. | |

Flag  Emblem | |

| Nickname(s): JB, Bandaraya Selatan (Southern City) | |

| Motto(s): Johor Bahru Bandar Raya Bertaraf Antarabangsa, Berbudaya dan Lestari (English: Johor Bahru, an International, Cultural and Sustainable City) | |

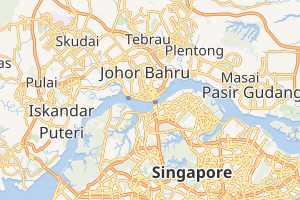

Location of Johor Bahru in Johor | |

| Coordinates: 01°27′20″N 103°45′40″E | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| District | Johor Bahru |

| Administrative areas | List

|

| Historic countries | |

| Founded | 10 March 1855 (as Tanjung Puteri) |

| Granted municipality status | 1 April 1977 |

| Granted city status | 1 January 1994 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Johor Bahru City Council |

| • Mayor | Dato' Haji Adib Azhari Bin Daud |

| Area | |

| • City and state capital | 220.00 km2 (84.94 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,064 km2 (411 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,217 km2 (856 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 32 m (105 ft) |

| Population (2010)[3] | |

| • City and state capital | 663,307 |

| • Density | 2,259/km2 (5,850/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,277,244 (3rd) |

| • Urban density | 1,200/km2 (3,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,805,000 |

| • Metro density | 814/km2 (2,110/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Johor Bahruans |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+8 (Not observed) |

| Postal code | 80xxx to 81xxx |

| Area code(s) | 07 |

| Vehicle registration | J |

| Website | www |

Johor Bahru was founded in 1855 as Tanjung Puteri when the Sultanate of Johor came under the influence of Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim. The area was renamed "Johore Bahru" in 1862 and became the capital of the Sultanate when the Sultanate administration centre was moved there from Telok Blangah.[6]

During the reign of Sultan Abu Bakar, there was development and modernisation within the city; with the construction of administrative buildings, schools, religious buildings, and railways connecting to Woodlands in Singapore. Johor Bahru was occupied by the Japanese forces from 1942 to 1945. Johor Bahru became the cradle of Malay nationalism after the war and gave birth to a political party named United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) in 1946. After the formation of Malaysia in 1963, Johor Bahru retained its status as state capital and was granted city status in 1994.

Etymology

The present area of Johor Bahru was originally known as Tanjung Puteri, and was a fishing village of the Malays. Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim then renamed Tanjung Puteri to Iskandar Puteri once he arrived in the area in 1858 after acquiring the territory from Sultan Ali;[7] before it was renamed Johor Bahru by Sultan Abu Bakar following the Temenggong's death.[6] (The suffix "Bah(a)ru" means "new" in Malay, normally written "baru" in standard spelling today but appearing with several variants in place names, such as Kota Bharu and Indonesian Pekanbaru.) The British preferred to spell its name as Johore Bahru or Johore Bharu,[8] but the current accepted western spelling is Johor Bahru, as Johore is only spelt Johor (without the letter "e" at the end of the word) in Malay language.[9][10] The city is also spelt as Johor Baru or Johor Baharu.[11][12]

The city was also once known as "Little Swatow (Shantou)" by the Chinese community in Johor Bahru, as most of Johor Bahru's Chinese residents are Teochew people whose ancestry can be traced back to Shantou, China. They arrived in the mid 19th century, during the reign of Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim.[13]

History

Due to a dispute between the Malays and the Bugis, the Johor-Riau Sultanate was split in 1819 with the mainland Johor Sultanate came under the control of Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim while the Riau-Lingga Sultanate came under the control of the Bugis.[14][15] The Temenggong intended to create a new administration centre for the Johor Sultanate to create a dynasty under the entity of Temenggong.[16] As the Temenggong already had a close relationship with the British and the British intended to have control over trade activities in Singapore, a treaty was signed between Sultan Ali and Temenggong Ibrahim in Singapore on 10 March 1855.[17] According to the treaty, Ali would be crowned as the Sultan of Johor and receive $5,000 (in Spanish dollars) with an allowance of $500 per month.[18] In return, Ali was required to cede the sovereignty of the territory of Johor (except Kesang of Muar which would be the only territory under his control) to Temenggong Ibrahim.[18] When both sides agreed on Temenggong acquiring the territory, he renamed it Iskandar Puteri and began to administer it from Telok Blangah in Singapore.[6]

As the area was still an undeveloped jungle, Temenggong encouraged the migration of Chinese and Javanese to clear the land and to develop an agricultural economy in Johor.[19] The Chinese planted the area with black pepper and gambier,[20] while the Javanese dug parit (canals) to drain water from the land, build roads and plant coconuts.[21] During this time, a Chinese businessman, pepper and gambier cultivator, Wong Ah Fook arrived; at the same time, Kangchu and Javanese labour contract systems were introduced by the Chinese and Javanese communities.[19][22][23] After Temenggong's death on 31 January 1862, the town was renamed "Johor Bahru" and his position was succeeded by his son, Abu Bakar, with the administration centre in Telok Blangah being moved to the area in 1889.[6]

British administration

In the first phase of Abu Bakar's administration, the British only recognised him as a maharaja rather than a sultan. In 1855, the British Colonial Office began to recognise his status as a Sultan after he met Queen Victoria.[24] He managed to regain Kesang territory for Johor after a civil war with the aid of British forces and he boosted the town's infrastructure and agricultural economy.[24][25] Infrastructure such as the State Mosque and Royal Palace was built with the aid of Wong Ah Fook, who had become a close patron for the Sultan since his migration during the Temenggong reign.[26] As the Johor-British relationship improved, Abu Bakar also set up his administration under a British style and implemented a constitution known as Undang-undang Tubuh Negeri Johor (Johor State Constitution).[24] Although the British had long been advisers for the Sultanate of Johor, the Sultanate never came under direct colonial rule of the British.[27] The direct colonial rule only came into effect when the status of the adviser was elevated to a status similar to that of a Resident in the Federated Malay States (FMS) during the reign of Sultan Ibrahim in 1914.[28]

In Johor Bahru, the Malay Peninsula railway extension was finished in 1909,[29] and in 1923 the Johor–Singapore Causeway was completed.[30] Johor Bahru developed at a modest rate between the First and Second World Wars. The secretariat building—Sultan Ibrahim Building—was completed in 1940 as the British colonial government attempted to streamline the state's administration.[31]

World War II

The continuous development of Johor Bahru was, however, halted when the Japanese under General Tomoyuki Yamashita invaded the town on 31 January 1942. As the Japanese had reached northwest Johor by 15 January, they easily captured major towns of Johor such of Batu Pahat, Yong Peng, Kluang and Ayer Hitam.[32] The British and other Allied forces were forced to retreat towards Johor Bahru; however, following a further series of bombings by the Japanese on 29 January, the British retreated to Singapore and blew up the causeway the following day as a final attempt to stop the Japanese advance in British Malaya.[32] The Japanese then used the Sultan's residence of Bukit Serene Palace located in the town as their main temporary base for their future initial plans to conquer Singapore while waiting to reconnect the causeway.[33][34] The Japanese chose the palace as their main base because they already knew the British would not dare to attack it as this would harm their close relationship with Johor.[32]

In less than a month, the Japanese repaired the causeway and invaded the Singapore island easily.[35] Soon after the war ended in 1946, the town became the main hotspot for Malay nationalism in Malaya. Onn Jaafar, a local Malay politician who later became the Chief Minister of Johor, formed the United Malay National Organisation party on 11 May 1946 when the Malays expressed their widespread disenchantment over the British government's action for granting citizenship laws to non-Malays in the proposed states of the Malayan Union.[36][37] An agreement over the policy was then reached in the town with Malays agreeing with the dominance of economy by the non-Malays and the Malays' dominance in political matters being agreed upon by non-Malays.[38] Racial conflict between the Malay and non-Malays, especially the Chinese, is being provoked continuously since the Malayan Emergency.[39]

Post-independence

After the formation of the Federation of Malaysia in 1963,[40] Johor Bahru continued as the state capital and more development was carried out, with the town's expansion and the construction of more new townships and industrial estates. The Indonesian confrontation did not directly affect Johor Bahru as the main Indonesian landing point in Johor was in Labis and Tenang in Segamat District as well Pontian District.[41][42] There is only one active Indonesian spy organisation in the town, known as Gerakan Ekonomi Melayu Indonesia (GEMI). They frequently engaged with the Indonesian communities living there to contribute information for Indonesian commandos until the bombing of the MacDonald House in Singapore in 1965.[43][note 1] By the early 1990s, the town had considerably expanded in size, and was officially granted a city status on 1 January 1994.[44] Johor Bahru City Council was formed and the city's current main square, Dataran Bandaraya Johor Bahru, was constructed to commemorate the event. A central business district was developed in the centre of the city from the mid-1990s in the area around Wong Ah Fook Street. The state and federal government channelled considerable funds for the development of the city—particularly more so after 2006, when the Iskandar Malaysia was formed.[45][46] However, more than 10 years of unbridled building construction in Iskandar, especially of higher end high-rise apartments and commercial property, has led to a serious glut of such property in the region. Occupancy of high-rise accommodation has been predicted to fall to 50 percent, and commercial property to 65 percent, by the end of 2019 due to continued incoming supply.[47]

Governance

As the capital city of Johor, the city plays an important role in the economic welfare of the population of the entire state. There is one member of parliament (MP) representing the single parliamentary constituency (P.160) in the city. The city also elects two representatives to the state legislature from the state assembly districts of Larkin and Stulang.[48]

Local authority and city definition

The city is administered by the Johor Bahru City Council. The current mayor is Amran bin A. Rahman which took office since 23 July 2018.[49][50] Johor Bahru obtained city status on 1 January 1994.[44] The area under the jurisdiction of the Johor Bahru City Council includes Central District, Kangkar Tebrau, Kempas, Larkin, Majidee, Maju Jaya, Mount Austin, Pandan, Pasir Pelangi, Pelangi, Permas Jaya, Rinting, Tampoi, Tasek Utara and Tebrau.[51] This covers an area of 220 square kilometres (85 sq mi).[1] Currently there are 11 council members in the city council, which consists of 3 Amanah members, 3 Bersatu members, 3 DAP members and 2 PKR members.[52]

Courts of law and legal enforcement

The city high court complex is located along Dato' Onn Road.[53] The Sessions and Magistrate Courts is located on Ayer Molek Road,[53] while another court for Sharia law is located on Abu Bakar Road.[54] The Johor (state) Police Contingent Headquarters is located on Tebrau Road.[55] Johor Bahru's Southern District police headquarters, which also operates as a police station, is on Meldrum Road in the city centre. The Johor Bahru Southern District traffic police headquarters is a separate entity along Tebrau Road, close to the city centre. Johor Bahru's Northern District police headquarters and Northern District Traffic Police headquarters are co-located in Skudai, about 20 km north of the city centre. There are around eleven police stations and seven police substations (Pondok Polis) in the greater Johor Bahru area.[56][57] Johor Bahru Prison was located in the city along Ayer Molek Road, but was closed down after 122 years operation in December 2005,[58][59] its function being transferred to an expanded prison in the town of Kluang about 110 km from Johor Bahru.[58] Other temporary lock-ups or prison cells are available in most police stations in the city, as in other parts of Malaysia.[60]

Geography

Johor Bahru is located along the Straits of Johor at the southern end of Peninsular Malaysia.[61] Originally, the city area was only 12.12 km2 (4.68 sq mi) in 1933 before been expanded to over 220 km2 (85 sq mi) in 2000.[1]

Climate

The city has an equatorial climate with consistent temperatures, a considerable amount of rain, and high humidity throughout the course of the year. An equatorial climate is a tropical rainforest climate more subject to the Intertropical Convergence Zone than the trade winds and with no cyclone. Daily average temperatures range from 26.4 °C (79.5 °F) in January to 27.8 °C (82.0 °F) in April with an average annual rainfall of around 2,350 mm (93 in).[62] The wettest months, with 19 to 25 percent more rain than average, are April, November and December.[63] Although the climate is relatively uniform, it does show some seasonal variation due to the effects of monsoons, with noticeable changes in wind speed and direction, cloud cover and amount of rainfall. There are two monsoon periods each year, the first one between mid-October and January, which is the north-east Monsoon. This period is characterised by heavier rainfall and wind from the north-east. The second one is the south-west Monsoon, which hardly affects the rainfall in Johor Bahru, where winds are from the south and south-west. This occurs between June and September.[64]

| Climate data for Johor Bahru (1974–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.0 (87.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.5 (90.5) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.5 (90.5) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.9 (71.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 162.6 (6.40) |

139.8 (5.50) |

203.4 (8.01) |

232.8 (9.17) |

215.3 (8.48) |

148.1 (5.83) |

177.0 (6.97) |

185.9 (7.32) |

190.8 (7.51) |

217.7 (8.57) |

237.6 (9.35) |

244.5 (9.63) |

2,355.5 (92.74) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 162 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organisation[63] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Johor Bahru has an official demonym where people are commonly referred to as "Johor Bahruans". The terms "J.B-ites" and "J.B-ians" have also been used to a limited extent. People from Johor are called Johoreans.[65]

Ethnicity and religion

The Malaysian Census in 2010 reported the population of Johor Bahru as 497,067.[3] The city's population today is a mixture of three main ethnicities - Malays, Chinese and Indians- along with other bumiputras. Malays comprise a plurality of the population at 240,323, followed by Chinese totalling 172,609, Indians totaling 73,319 and others totalling 2,957.[3] Non-Malaysian citizens form a population of 2,585.[3] The Malays in Johor are strongly related to the neighbouring Riau Malays.[66][67] The Chinese mainly are from the majority Teochew, Hokkien, Hainanese, and Hakka dialect groups,[13] while the Indian community mainly and predominantly are Tamils. There are also small populations of Malayalis, Telugus and Sikh Punjabis. The Malays are majority Muslims, while the Chinese are predominantly Buddhists and the Indian were mostly Hindus despite there is also a small numbers from the two ethnic groups that are Christians and Muslims. A small number of Sikhs, Taoists, Animists, and secularists can also be found in the city.

The following is based on Department of Statistics Malaysia 2010 census.[3]

| Ethnic groups in Johor Bahru, 2010 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Population | Percentage |

| Malay | 240,323 | 48.35% |

| Other Bumiputras | 5,374 | 1.98% |

| Chinese | 172,609 | 34.73% |

| Indian | 73,319 | 13.70% |

| Others | 2,957 | 0.59% |

| Non-Malaysian | 2,585 | 1.57% |

| Total | 497,067 | 100.00% |

Languages

The local ethnic Malays speak the Malay language,[66] while the language primarily spoken by the local Chinese is Mandarin Chinese. The Chinese community is represented by several dialect groups: Teochew, Hainanese, Hakka and Hokkien.[32][68] The Indian community predominantly speaks Tamil, with a minority of Malayalam, Telugu and Punjabi speakers. The English language (or Manglish) is also used considerably, albeit more so among the older generation, who have attended school during the British rule.[69]

Economy

Johor Bahru is one of the fastest-growing cities in Malaysia after Kuala Lumpur.[70] In 2010, the city contributed the second largest GDP in Malaysia, after Kuala Lumpur.[71] It is the main commercial centre for Johor and is located in the Indonesia–Malaysia–Singapore Growth Triangle. Tertiary-based industry dominates the economy with many international tourists from the regions visiting the city.[70][72][73] It is the centre of financial services, commerce and retail, arts and culture, hospitality, urban tourism, plastic manufacturing, electrical and electronics and food processing.[74] The main shopping districts are located within the city, with a number of large shopping malls located in the suburbs. Johor Bahru is the location of numerous conferences, congress and trade fairs, such as the Eastern Regional Organisation for Planning and Housing and the World Islamic Economic Forum.[75][76] The city is the first in Malaysia to practise a low-carbon economy.[77]

The city has a very close economic relationship with Singapore. There are around 3,000 logistic lorries crossing between Johor Bahru and Singapore every day for delivering goods between the two sides for trading activities.[78] Many residents in Singapore frequently visit the city during the weekends; some of them have also chosen to live in the city.[70][72][73][79][80] Many of the city's residents work in Singapore.[81][82] In 2014, the sudden change by the Sultan of Johor of weekend rest days from Saturday and Sunday to Friday and Saturday had a relatively small impact to the city economy, with business especially affected. However, it could boost the tourism industry, since shops can now open on Sunday, attracting more tourists from Singapore.[83]

Transportation

Land

The internal roads linking different parts of the city are mostly federal roads constructed and maintained by Malaysian Public Works Department. There are five major highways linking the Johor Bahru Central Business District to outlying suburbs: Tebrau Highway and Johor Bahru Eastern Dispersal Link Expressway in the northeast, Skudai Highway in the northwest, Iskandar Coastal Highway in the west and Johor Bahru East Coast Highway in the east.[74] Pasir Gudang Highway and the connecting Johor Bahru Parkway cross Tebrau Highway and Skudai Highway, which serve as the middle ring road of the metropolitan area. The Johor Bahru Inner Ring Road, which connects with the Sultan Iskandar customs complex, aids in controlling the traffic in and around the central business district.[74] Access to the national expressway is provided through the North–South Expressway and Senai–Desaru Expressway.[84] The Johor–Singapore Causeway links the city to Woodlands, Singapore with a six-lane road and a railway line terminating at the Southern Integrated Gateway.[74]

Bus

The main bus terminal of the city is the Larkin Sentral located in Larkin.[85] Other bus terminals include Taman Johor Jaya Bus Terminal[86] and Ulu Tiram Bus Terminal.[87] Larkin Sentral has direct bus services to and from many destinations in West Malaysia, southern Thailand and Singapore, while Taman Johor Jaya and Ulu Tiram Bus Terminals serve local destinations.[85] Major bus operators in the city are Causeway Link, Maju and S&S. It is possible to get around the city by bus, though the frequency of the bus might be an issue. An independent community effort, businterchange.net, features a comprehensive bus service information including their fleets and services.

Taxi

Two types of taxis operate in the city; the main taxi is either in red and yellow, blue, green or red while the larger, less common type is known as a limousine taxi, which is more comfortable but expensive. Most taxis in the city do not use their meter.[88]

Railway

The city is served by two railway stations, which are Johor Bahru Sentral railway station[89] and Kempas Baru railway station. Both stations serve train services to Kuala Lumpur and Singapore. In 2015, a new shuttle train service operated by Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM) was launched providing transport to Woodlands in Singapore.[90]

Air

The city is served by Senai International Airport located at the neighbouring Senai town and connected through Skudai Highway.[91] Five airlines, AirAsia, Firefly, Malaysia Airlines, Malindo Air and Xpress Air, provide flights internationally and domestically.[92][93]

Sea

Boat services are available to ports in Batam and Bintan Islands in Indonesia from Stulang Laut Ferry Terminal, located near the suburb of Stulang.[91][94] There are also boat services to Batam and Tanjung Balai Karimun from Puteri Harbour International Ferry Terminal located in Iskandar Puteri.[95]

Other utilities

Healthcare

There are three public hospitals,[96] four health clinics[97] and thirteen 1Malaysia clinics in Johor Bahru.[98] Sultanah Aminah Hospital, which is located along Persiaran Road, is the largest public hospital in Johor Bahru as well as in Johor with 989 beds.[97] Another government funded hospital is the Sultan Ismail Specialist Hospital with 700 beds.[97] Another large private health facility is the KPJ Puteri Specialist Hospital with 158 beds.[99] Further healthcare facilities are currently being expanded to improve healthcare services in the city.[100]

Education

Many government or state schools are available in the city. The secondary schools include English College Johore Bahru, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Engku Aminah, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Sultan Ismail, Sekolah Menengah Infant Jesus Convent, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan (Perempuan) Sultan Ibrahim and Sekolah Menengah Saint Joseph.[101] There are also a number of independent private schools in the city. These include Austin Heights,[102] Excelsior International School,[103] Foon Yew High School and the Sri Ara Schools. The Sri Ara Schools provide two curricula, the British-based curriculum of International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) under Cambridge International Examinations and the National Curriculum with emphasis on the English language that leads to the Malaysian Schools Certificate.[104] The other private universities are Raffles University Iskandar and Wawasan Open University. There are also a number of private college campuses and one polytechnic operating in the city; these are Crescendo International College, KPJ College, Olympia College, Sunway College Johor Bahru, Taylor's College and College of Islamic Studies Johor.[105]

Libraries

The Johor Public Library headquarters is the main library in the state, located off Yahya Awal Road.[106] Another public library branch is the University Park in Kebudayaan Road, while there are other libraries or private libraries in schools, colleges, and universities.[107] Two village libraries are available in the district of Johor Bahru.[108]

Culture and leisure

Attractions and recreation spots

Cultural attractions

There are a number of cultural attractions in Johor Bahru. The Royal Abu Bakar Museum located within the Grand Palace building is the main museum in the city. The Johor Bahru Kwong Siew Heritage located in Wong Ah Fook Street housed the former Cantonese clan house that was donated by Wong Ah Fook.[109] The Foon Yew High School houses many historical documents of the city history with a Chinese cultural heritage.[110][111][112] The Johor Bahru Chinese Heritage Museum on Ibrahim Road includes the history of Chinese migration to Johor along with a collection of documents, photos, and other artefacts.[113] The Arts Plaza (Plaza Seni) on the Wong Ah Fook Street features the state heritage and cultures with exhibitions of art, cultural performances, clothes, fashion accessories, travel agencies, and batik fabrics.[114]

The Johor Art Gallery in Petrie Road is a house gallery built in 1910, known as the house for the former third Chief Minister of Johor, Abdullah Jaafar. The house features old architecture and became the centre for the collection of artefacts related to Johor's cultural history since its renovation in 2000.[112]

Historical attractions

The Grand Palace is one of the historical attractions in the city, and is an example of Victorian-style architecture with a garden. Figure Museum is another historical colonial building since 1886 which ever become the house for the Johor first Menteri Besar Jaafar Mohamed; it is located on the top of Smile Hill (Bukit Senyum).[115] The English College (now Maktab Sultan Abu Bakar) established in 1914 was located close to the Sungai Chat Palace before being moved to its present location at Sungai Chat Road; some of the ruins are visible at the old site.[25] The Sultan Ibrahim Building is another historical building in the city; built in 1936 by British architect Palmer and Turner, it was the centre of the administration of Johor as since the relocation from Telok Blangah in Singapore, the Johor government never had its own building.[112][116] Before the current railway station was built, there was Johor Bahru railway station (formerly Wooden Railway) which has now been turned into a museum after serving for 100 years since the British colonial era.[114]

Sultan Abu Bakar State Mosque, located along Skudai Road, is the main and the oldest mosque in the state. It was built with a combination of Victorian, Moorish and Malay architectures.[112][117] The Johor Bahru Old Chinese temple, located on the Trus Road, dedicated to the Five Patron Deities from the five Southern Chinese Clans (Hokkien, Teochew, Hakka, Cantonese & Hainanese) in the city. It was built in 1875 and renovated by the Persekutuan Tiong Hua Johor Bahru (Johor Bahru Tiong Hua Association) in 1994–95 with the addition of a small L-shaped museum in one corner of the square premises.[20] The Wong Ah Fook Mansion, the home of the late Wong Ah Fook, was a former historical attraction. It stood for more than 150 years but was demolished illegally by its owner in 2014 to make way for a commercial housing development without informing the state government.[118][119] Other historical religious buildings include the Arulmigu Sri Rajakaliamman Hindu Temple, Sri Raja Mariamman Hindu Temple, Gurdwara Sahib and Church of the Immaculate Conception.[114][115]

Leisure and conservation areas

The Danga Bay is a 25 kilometres (16 mi) area of recreational waterfront. There are around 15 established golf courses, of which two offer 36-hole facilities; most of these are located within resorts. The city also features a number of paintball parks which are also used for off-road motorsports activities.[114]

The Johor Zoo is one of the oldest zoos in Malaysia; built in 1928 covering 4 hectares (9.9 acres) of land, it was originally called "animal garden" before being handed to the state government for renovation in 1962.[120] The zoo has around 100 species of animals, including wild cats, camels, gorillas, orangutans, and tropical birds.[121] Visitors can participate in activities such as horse riding or using pedalos.[112]

Other attractions

Dataran Bandaraya was built after Johor Bahru was proclaimed as a city. The site features a clock tower, fountain and a large field.[112] The Tun Sri Lanang Park, named after Tun Sri Lanang (Bendahara of the royal Court of the Johor Sultanate in the 16th and 17th centuries) is located in the centre of the city. The Wong Ah Fook Street is named after Wong Ah Fook. The Tam Hiok Nee Street is named after Tan Hiok Nee, who was the leader of the former Ngee Heng Kongsi, a secret society in Johor Bahru. Together with the Dhoby Street, both are part of a trail known as Old Buildings Road; they feature a mixture of Chinese and Indian heritages, reflected by their forms of ethnic business and architecture.[114][115]

Shopping

Shopping malls in Johor Bahru include Komtar JBCC, KSL City, Johor Bahru City Square, R&F Mall, Holiday Plaza, Paradigm Mall Johor Bahru, The Mall Mid Valley Southkey, Toppen Shopping Centre, Plaza Pelangi, Galleria@Kotaraya, AEON Tebrau City, Paragon Market Place, AEON Permas Jaya, Pelangi Leisure Mall, AEON Mall Bandar Dato' Onn, Plaza Sentosa, Stellar Walk and Beletime Danga Bay. The Mawar Handicrafts Centre, a government-funded exhibition and sales centre, is located along the Sungai Chat road and sells various batik and songket clothes.[35] Opposite this is the Johor Area Rehabilitation Organisation (JARO) Handicrafts Centre which sells items such as hand-made cane furniture, soft toys and rattan baskets made by the physically disabled.[114][122]

Entertainment

.jpg)

The oldest cinema in the city is the Broadway Theatre which mostly screens Tamil and Hindi movies. There are around five new cinemas available in the city with most of them located inside shopping malls.[114]

Crime

For several decades running, Johor Bahru is notorious for its relatively high crime rate, compared to other urban areas in Malaysia. In 2014, Johor Bahru South police district recorded one of the highest crime rates in the country with 4,151 cases, behind Petaling Jaya.[127] In 2013, the city also accounted for 70% of crimes committed in the entire state of Johor, with a Johor police spokesman admitting that Johor Bahru remained a crime hotspot within the state.[128] Crime in Johor Bahru has also received substantial media coverage by the Singaporean press, as Singaporeans visiting or transiting through the neighbouring city are often targeted by criminals.[128][129][130]

Among the more common criminal cases in Johor Bahru are robberies, snatch theft, carjacking, kidnapping and rape.[128][131][132] Gang and unarmed robberies accounted for about 76% of the city's criminal cases in 2013 alone.[131] Illegal car cloning is also rampant in the city.[133] In addition, Johor Bahru's reputation for sleaze still exists, with some areas in the city centre turning into red-light districts, despite prostitution being illegal in Malaysia.[134][135]

International relations

Several countries have set up their consulates in Johor Bahru, including Indonesia[136] and Singapore, while Japan has closed its consular office since 2014.[137]

Notable people

- Christina Jordan (born 1962), Malaysian-born British politician[146]

See also

- Johor Bahru landmarks

- Johor Bahru Central District

In popular culture

Movies

- Punggok Rindukan Bulan (2008)

Notes

- Another early attack to destabilise Malaysia was done with the murder of Malay trishaw in Singapore that led to the racial conflict between Malay and Chinese there. At the first stage of the conflict, it was alleged the murder was done by a Chinese but this was however turned down when further investigation revealed the murder was actually done by Indonesian agents who had infiltrate Singapore in an attempt to weakening the unity of race there during the state was still part of Malaysia. (Drysdale, Halim and Jamie)

References

- "Background (Total Area)". Johor Bahru City Council. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "Malaysia Elevation Map (Elevation of Johor Bahru)". Flood Map : Water Level Elevation Map. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "Total population by ethnic group, Local Authority area and state, Malaysia" (PDF). Statistics Department, Malaysia. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- "Biggest Cities In Malaysia". World Atlas. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "JB can be Malaysia's second-biggest city: Johor Sultan". The Star/Asia News Network. The Straits Times. 24 March 2016. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Background of Johor Bahru City Council and History of Johor Bahru" (PDF). Malaysian Digital Repository. 12 March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Zainol Abidin Idid (Syed.) (19??). Pemeliharaan warisan rupa bandar: panduan mengenali warisan rupa bandar berasaskan inventori bangunan warisan Malaysia (in Malay). Badan Warisan Malaysia. ISBN 978-983-99554-1-5. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Margaret W. Young; Susan L. Stetler; United States. Department of State (October 1985). Cities of the world: a compilation of current information on cultural, geograph. and polit. conditions in the countries and cities of 6 continents, based on the Dep. of State's "Post Reports". Gale. ISBN 978-0-8103-2059-8.

- Gordon D. Feir (10 September 2014). Translating the Devil: Captain Llewellyn C Fletcher Canadian Army Intelligence Corps In Post War Malaysia and Singapore. Lulu Publishing Services. pp. 378–. ISBN 978-1-4834-1507-9.

- Cheah Boon Kheng (1 January 2012). Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation, 1941–1946. NUS Press. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-9971-69-508-8.

- Carl Parkes (1994). Southeast Asia Handbook. Moon Publications.

- Library of Congress (2009). Library of Congress Subject Headings. Library of Congress. pp. 4017–.

- "Keeping the art of Teochew opera alive". New Straits Times. AsiaOne. 24 July 2010. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- Donald B. Freeman (17 April 2003). Straits of Malacca: Gateway or Gauntlet?. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-0-7735-7087-0.

- Kanji Nishio (2007). Bangsa and Politics: Melayu-Bugis Relations in Johor-Riau and Riau-Lingga.

- M. A. Fawzi Mohd. Basri (1988). Johor, 1855–1917: pentadbiran dan perkembangannya (in Malay). Fajar Bakti. ISBN 978-967-933-717-4.

- "Johor Treaty is signed". National Library Board. 10 March 1855. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Abdul Ghani Hamid (3 October 1988). "Tengku Ali serah Johor kepada Temenggung (Kenangan Sejarah)" (in Malay). Berita Harian. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- "History of the Johor Sultanate". Coronation of HRH Sultan Ibrahim. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- S. Muthiah (19 June 2015). "The city that gambier built". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Carl A. Trocki (2007). Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore, 1784–1885. NUS Press. pp. 152–. ISBN 978-9971-69-376-3.

- Patricia Pui Huen Lim (1 July 2000). Oral History in Southeast Asia: Theory and Method. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-981-230-027-0.

- Patricia (2002), p. 129–132

- Muzaffar Husain Syed; Syed Saud Akhtar; B D Usmani (14 September 2011). Concise History of Islam. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. pp. 316–. ISBN 978-93-82573-47-0.

- Dominique Grele (1 January 2004). 100 Resorts Malaysia: Places with a Heart. Asiatype, Inc. pp. 292–. ISBN 978-971-0321-03-2.

- Cheah Jin Seng (15 March 2008). Malaya: 500 Early Postcards. Didier Millet Pte, Editions. ISBN 978-981-4155-98-4.

- Fr Durand; Richard Curtis (28 February 2014). Maps of Malaysia and Borneo: Discovery, Statehood and Progress. Editions Didier Millet. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-967-10617-3-2.

- "Johor is brought under British control". National Library Board. 12 May 1914. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Winstedt (1992), p. 141

- Winstedt (1992), p. 143

- Oakley (2009), p. 181

- Patricia Pui Huen Lim; Diana Wong (1 January 2000). War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 140–145. ISBN 978-981-230-037-9.

- Richard Reid. "War for the Empire: Malaya and Singapore, Dec 1941 to Feb 1942". Australian War Memorial. Australia-Japan Research Project. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- Bill Yenne (20 September 2014). The Imperial Japanese Army: The Invincible Years 1941–42. Osprey Publishing. pp. 140–. ISBN 978-1-78200-982-5.

- Wendy Moore (1998). West Malaysia and Singapore. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 186–187. ISBN 978-962-593-179-1.

- Swan Sik Ko (1990). Nationality and International Law in Asian Perspective. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 314–. ISBN 978-0-7923-0876-8.

- Keat Gin Ooi (1 January 2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1365–. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2.

- Christoph Marcinkowski; Constance Chevallier-Govers; Ruhanas Harun (2011). Malaysia and the European Union: Perspectives for the Twenty-first Century. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-3-643-80085-5.

- M. Stenson (1 November 2011). Class, Race, and Colonialism in West Malaysia. UBC Press. pp. 89–. ISBN 978-0-7748-4440-6.

- Arthur Cotterell (15 July 2014). A History of South East Asia. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. pp. 341–. ISBN 978-981-4634-70-0.

- K. Vara (16 February 1989). "Quiet town with a troubled past". New Straits Times. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- "Indonesian Confrontation, 1963–66". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Mohamed Effendy Abdul Hamid; Kartini Saparudin (2014). "MacDonald House bomb explosion". National Library Board. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- "Background" (in English and Malay). Johor Bahru City Council. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- Zaini Ujang (2009). The Elevation of Higher Learning. ITBM. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-983-068-464-2.

- Oxford Business Group Malaysia (2010). The Report: Malaysia 2010 – Oxford Business Group. Oxford Business Group. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-1-907065-20-0.

- Rachel Chew (16 January 2019). "JB's high-rise residences vacancy rate expected to hit an unprecedented above 50% this year". www.edgeprop.my. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "List of Parliamentary Elections Parts and State Legislative Assemblies on Every States". Ministry of Information Malaysia. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Sesi 'Clock In' Datuk Bandar MBJB Ke 11 Tuan Haji Amran bin A.Rahman". Johor Bahru City Council (in Malay). 23 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "Mayor's Profile". Johor Bahru City Council. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- "Administrative areas of Johor Bahru City Council". Johor Bahru City Council. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- "MBJB laksana kaedah pentadbiran baharu" (in Malay). Sinar Online. 17 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "Senarai Mahkamah Johor" (in Malay). Johor Law Courts Official Website. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Johore Syariah Court Directory". E-Syariah Malaysia. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Johor Police Contingent". Johor Police Contingent. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Direktori PDRM Johor – Johor Bahru (Utara)" (in Malay). Royal Malaysia Police. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Direktori PDRM Johor – Johor Bahru (Selatan)" (in Malay). Royal Malaysia Police. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Penjara Johor Bahru Dalam Kenangan" (in Malay). Prison Department of Malaysia. 12 December 2007. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Prison Address & Directory". Prison Department of Malaysia. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Soalan Lazim (Frequently Asked Questions)" (in Malay). Prison Department of Malaysia. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Eric Wolanski (18 January 2006). The Environment in Asia Pacific Harbours. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 349–. ISBN 978-1-4020-3654-5.

- "Weather Data For Johor Bahru". Weatherbase. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "World Weather Information Service – Johor Bahru". World Meteorological Organisation. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Malaysia". Climates To Travel. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Nelson Benjamin (28 April 2015). "Sultan wants all Johoreans to unite". The Star. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Susanna Cumming (9 August 2011). Functional Change: The Case of Malay Constituent Order. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-3-11-086454-0.

- Peter Borschberg (2016). "Singapore and its Straits, c.1500–1800". Indonesia and the Malay World. Taylor & Francis. 45 (133): 373–390. doi:10.1080/13639811.2017.1340493.

- Robbie B.H. Goh (1 March 2005). Contours of Culture: Space and Social Difference in Singapore. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-962-209-731-5.

- "Johor Sultan: English in danger of becoming older people's language". The Malay Mail. 28 December 2015. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "Johor Bahru, a city on the move". South China Morning Post. 31 August 1996. Archived from the original on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- "Johor Bahru". Khazanah Nasional Malaysia.

- Aldo Tri Hartono (11 August 2014). "Wisata Belanja di Malaysia, Johor Bahru Tempatnya" (in Indonesian). DetikCom. Archived from the original on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- "Menikmati Johor Bahru Selangkah dari Singapura" (in Indonesian). Jawa Pos Group. 4 July 2015. Archived from the original on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "Flagship A: Johor Bahru City". Iskandar Regional Development Authority. Iskandar Malaysia. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- "46th EAROPH Regional Conference, Iskandar, Malaysia, Thistle Hotel, Johor Bahru" (PDF). Eastern Regional Organisation for Planning and Housing. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- "8th WIEF Johor Bahru, Malaysia". 8th World Islamic Economic Forum. 2012. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- "Low carbon city report focus on Johor Bahru, Malaysia". British High Commission, Kuala Lumpur. Government of the United Kingdom. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- "Malaysian transport, logistics providers welcome change in Woodlands Checkpoint toll charges". The Straits Times. 9 January 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "JB calling". The Straits Times. 7 July 2013. Archived from the original on 20 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Tash Aw (13 May 2015). "With more Singaporeans in Iskandar, signs of accelerating détente with Malaysia". The New York Times. The Malay Mail. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Zazali Musa (14 July 2015). "Lure of the Singapore dollar". The Star. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- "More M'sians prefer to earn S'pore wages". Daily Express. 15 July 2015. Archived from the original on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Dominic Loh (24 November 2013). "Changed weekends could impact Johor's economy". My Sinchew. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- "Chapter 15: Urban Linkage System (Section B: Planning and Implementation)" (PDF). Iskandar Malaysia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- "Larkin Bus Terminal". Express Bus Malaysia. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Johor Jaya Bus Terminal". Land Transport Guru. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Ulu Tiram Bus Terminal". Land Transport Guru. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Johor Bahru Taxi". Taxi Johor Bahru. Archived from the original on 20 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "From Singapore to KL by train". The Malaysia Site. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Singapore to Malaysia in just 5 minutes? It's now possible". The Straits Times/Asia News Network. Philippine Daily Inquirer. 5 July 2015. Archived from the original on 20 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Simon Richmond; Damian Harper (December 2006). Malaysia, Singapore & Brunei. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. pp. 247–253. ISBN 978-1-74059-708-1.

- "Malaysia's new airline in $1.5bn deal with Bombardier". BBC News. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- John Gilbert (30 October 2015). "October Launch For Flymojo Cancelled". The Malaysian Reserve. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "Stulang Laut Ferry Terminal". Easybook. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- "Puteri Harbour International Ferry Terminal". UEM Sunrise. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- "Direktori Hospital-Hospital Kerajaan" (in Malay). Johor State Health Department. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "Academic (Clinical) Vacancies" (PDF). Newcastle University Medical School. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "Direktori Hospital-Hospital Kerajaan" (in Malay). Johor State Health Department. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "About Us". KPJ Puteri Specialist Hospital. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "Healthcare projects in Iskandar Malaysia". Iskandar Regional Development Authority. Iskandar Malaysia. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH DI NEGERI JOHOR (List of Secondary Schools in Johor) – See Johor" (PDF). Educational Management Information System. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- "Private School". Austin Heights. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- "Home". Excelsior International School. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- "About Us (An Overview)". International School Johor. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- "Home" (in Malay). Kolej Pengajian Islam Johor. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "Lokasi Perbadanan Perpustakaan Awam Johor" (in Malay). Johor Public Library. Archived from the original on 9 August 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- "Perpustakaan Cawangan Seluruh Negeri Johor (Public Branches whole over the state of Johor)" (in Malay). Johor Public Library. Archived from the original on 9 August 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- "Perpustakaan Desa (Village Libraries)" (in Malay). Johor Public Library. Archived from the original on 9 August 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- Peggy Loh (18 December 2014). "Added advantage". New Straits Times. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Lim Mun Fah (10 August 2007). "Rise Up, Foon Yew! Move On, Independent Schools!". Sin Chew Daily. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Yee Xiang Yun (19 May 2013). "Great memories as Foon Yew High School turns 100". The Star. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "Lokasi-lokasi Menarik Berhampiran HSAJB (Interesting Spots Near Sultanah Aminah Hospital)" (PDF) (in Malay). Sultanah Aminah Hospital. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- Natalya (14 April 2013). "Chinese Heritage Museum". Johor Travel. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Guide to Iskandar Malaysia's Places of Interests". Iskandar Regional Development Authority. Iskandar Malaysia. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "History, Heritage, Arts and Culture, Crafts" (PDF). Malaysian Urological Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- "Sultan Ibrahim Building". National Archives. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- "Sultan Abu Bakar Mosque". Tourism Malaysia. Archived from the original on 19 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Desiree Tresa Gasper (2 May 2014). "150-year-old building torn down in middle of the night". The Star. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Johor govt issues writ of summons against Wong Ah Fook mansion owner for demolishment". Antara Pos. 9 May 2014. Archived from the original on 19 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Zoo Johor". Tourism Malaysia. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- Dees Stribling. "Zoos in Johor, Malaysia". USA Today. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- "Top 5 Places to Shop in Iskandar Malaysia". Iskandar Regional Development Authority. Iskandar Malaysia. Archived from the original on 20 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "Stadiums in Malaysia (Tan Sri Hassan Yunos)". World Stadiums. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- "About us". Sports Prima. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Mohd al Qayum Azizi (12 February 2015). "Best FM Bakal Beroperasi Di KL Awal Tahun Depan" (in Malay). mStar. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "FKE Seniors Gained First Hand Experience on Radio Station Operations For Their Capstone Projects". Department of Communication Engineering. Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. 4 October 2015. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "6,500 Anggota Polis Baharu Setiap Tahun Untuk Atasi Jenayah" (in Malay). mStar. 18 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Joseph Sipalan (11 November 2013). "Johor posts lower crime rate but capital still a hotspot, says top cop". The Malay Mail. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- "Top 10 crime zones in Johor Bahru". AsiaOne. 21 December 2015. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Clarence Fernandez (22 March 2007). "Singapore and Malaysia's Johor -- so near, yet so far". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Zubairu Abubakar Ghani (2017). "A comparative study of urban crime between Malaysia and Nigeria". Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Environmental Technology, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University. 6: 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.jum.2017.03.001.

- Farhana Syed Nokman (27 July 2017). "Johor has highest number of rape cases, Sabah tops incest numbers". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Norbaiti Phaharoradzi (6 April 2016). "Johor cops cripple car-cloning syndicate". The Star. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Ben Tan (6 October 2015). "JB still stuck with its past sleazy image". The Rakyat Post. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Ng Si Hooi; Gan Pei Ling (17 July 2017). "Foreign call girls look for 'uncles' at JB coffeeshops". The Star. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- "Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia, Johor Bahru". Consulate General of Indonesia, Johor Bahru, Johor, Malaysia. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- "Consular Office of Japan (Johor Bahru)". Embassy of Japan in Malaysia. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- Amanda (10 November 2016). "Changzhou, Johor Bahru of Malaysia become sister-cities". JSChina.com.cn. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- Liuxi (16 February 2012). "First Cultural Exchange after Shantou and Johor Bahru becomes Sister Cities". Shantou Daily. Shantou Government. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- "International Connections". Shantou Foreign and Oversea Chinese Affairs Bureau. Shantou Government. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Zazali Musa (10 March 2014). "Johor to strengthen trade and tourism activities with Guandong Province". The Star. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Yu Ji (27 August 2011). "Kuching bags one of only two coveted 'Tourist City Award' in Asia". The Star. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- "Malaysian investors in Cotabato City". CotabatoCity.net.ph. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- Helmut K Anheier; Yudhishthir Raj Isar (31 March 2012). Cultures and Globalization: Cities, Cultural Policy and Governance. SAGE Publications. pp. 376–. ISBN 978-1-4462-5850-7.

- "Relations between Turkey and Malaysia". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- "Home | Christina Sheila JORDAN | MEPs | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

Literature

- Guinness, Patrick (1992). On the Margin of Capitalism: People and development in Mukim Plentong, Johor, Malaysia. South-East Asian social monographs. Singapore: Oxford University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-19-588556-9. OCLC 231412873.

- Lim, Patricia Pui Huen (2002). Wong Ah Fook: Immigrant, Builder and Entrepreneur. Singapore: Times Editions. ISBN 978-981-232-369-9. OCLC 52054305.

- Oakley, Mat; Brown, Joshua Samuel (2009). Singapore: city guide. Footscray, Victoria, Australia: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-664-9. OCLC 440970648.

- Winstedt, Richard Olof; Kim, Khoo Kay (1992). A History of Johore, 1365–1941. M. B. R. A. S. Reprints (6) (Reprint ed.). Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. ISBN 978-983-99614-6-1. OCLC 255968795.

- John Drysdale (15 December 2008). Singapore Struggle for Success. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. pp. 287–. ISBN 978-981-4677-67-7.

- A Halim Hassan (September 2013). Meniti Impian (in Malay). Trafford Publishing. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-1-4907-0086-1.

- Jamie Han (2014). "Communal riots of 1964". National Library Board. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Johor Bahru. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Johor Bahru. |

.svg.png)