Aksu City

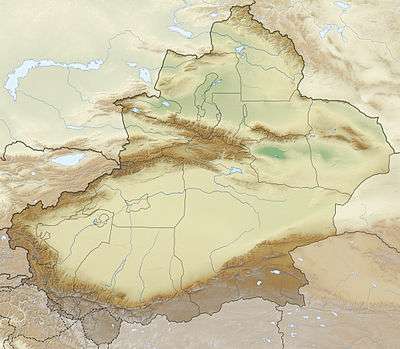

Aksu is a city in and the seat of Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang, lying at the northern edge of the Tarim Basin. The name Aksu literally means "white water" (in Turkic) and is used for both the oasis town and the Aksu River.

Aksu ئاقسۇ شەھىرى 阿克苏市 Akesu | |

|---|---|

Aksu pedestrian street | |

.png) Location of Aksu City (pink) in Aksu Prefecture and Xinjiang | |

Aksu Location of the city centre in Xinjiang | |

| Coordinates (Aksu City government): 41°11′06″N 80°17′25″E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Region | Xinjiang |

| Prefecture | Aksu |

| Township-level divisions | 7 subdistricts, 2 towns, 4 townships, 5 other areas |

| Area | |

| • County-level city | 14,668 km2 (5,663 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Urban (2018)[1] | 660,000 |

| Ethnic groups | |

| • Major ethnic groups | Uyghur, Han Chinese |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 843000 |

| Area code(s) | 0997 |

| Website | akss |

| Aksu City | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||

| Uyghur | ئاقسۇ | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 阿克苏市 | ||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 阿克蘇市 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The economy of Aksu is mostly agricultural, with cotton, in particular long-staple cotton, as the main product. Also produced are grain, fruits, oils and beets. The industry mostly consists of weaving, cement and chemical industries.

The land currently under the administration of the Aksu City is divided in two parts, separated by the Aral City. The northern part hosts the city center, while the southern part is occupied by the Taklamakan Desert.

Etymology

The name Aksu comes from the Uyghur word for "white water".[2] It is also transliterated Akesu, Ak-su, Akshu, Aqsu.

History

Gumo

From the Former Han dynasty (125 BCE to 23 CE) at least until the early Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), Aksu was known as Gumo 姑墨 [Ku-mo].[3][4] The ancient capital town of Nan ("Southern Town") was likely well south of the present town.

During the Han dynasty, Gumo is described as a "kingdom" (guo) containing 3,500 households and 24,500 individuals, including 4,500 people able to bear arms. It is said to have produced copper, iron and orpiment.[5] The territory of Gumo was roughly situated in the counties of Baicheng and Wensu and the city of Aksu of nowadays.[6]

Baluka

During the Buddhist era, it was known as Bharuka,[7] Bohuan and Baluka,[8] Bolujia (in pinyin), Po-lu-chia (in Wade-Giles).

The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang visited this "kingdom" in 629 CE and referred to it as Baluka.[9] He recorded that there were tens of Sarvastivadin Buddhist monasteries in the kingdom and over 1,000 monks. He said the kingdom was 600 li from east to west, and 300 li from north to south. Its capital was said to be six li in circumference. He reported that the "native products, climate, temperament of the people, customs, written language and law are the same as in the country of Kuci or modern Kucha, (some 300 km or 190 mi to the east), but the spoken language is somewhat different [from Kuchean]." He also stated that fine cotton and hemp cloth made in the area was traded in neighbouring countries.[10]

Contested period

In the 7th, 8th, and early 9th centuries, control of the entire region was often contested by the Chinese Tang dynasty, the Tibetan Empire, and the Uyghur Empire; cities frequently changed hands. Tibet seized Aksu in 670, but Tang forces reconquered the region in 692.

Tang dynasty Chinese General Tang Jiahui led the Chinese to defeat an Arab-Tibetan attack in the Battle of Aksu (717).[11] The attack on Aksu was joined by Turgesh Khan Suluk.[12][13] Both Uch Turfan and Aksu were attacked by the Turgesh, Arab, and Tibetan force on 15 August 717. Qarluqs serving under Chinese command, under Arsila Xian, a Western Turkic Qaghan serving under the Chinese Assistant Grand Protector General Tang Jiahui defeated the attack. Al-Yashkuri, the Arab commander and his army fled to Tashkent after they were defeated.[14][15]

Tibet regained the Tarim Basin in the late 720s, and the Tang dynasty again annexed the region in the 740s. The Battle of Talas led to the gradual withdrawal of Chinese forces, and the region was then contested between the Uyghurs and Tibetans.

Aksu was positioned on a junction of trade routes: the northern-Tarim route Silk road, and the dangerous route north via the Tian Shan's Muzart Pass to the fertile Ili River valley.[16]

Mongol era

In 1207–08, they submitted to Genghis Khan. Around 1220, Aksu became the capital of the Kingdom of Mangalai. The area had been part of the whole Mongol Empire before it was occupied by the independent-minded Chagatai Khanate under the House of Ogedei in 1286 from the hands of Kublai's Yuan Dynasty. After the decline of the Yuan Dynasty in the mid-14th century and subsequently the Chagatai Khanate in the late 14th century, Aksu fell under the power of Turkic and Mongol warlords.

Along with most of Xinjiang, Aksu fell under the control of the Khojas, and later that of Yaqub Beg, during the Dungan Rebellion of 1864–1877. Yakub Beg seized Aksu from Chinese Muslim forces.[17] After the defeat of the rebellion, a learned cleric named Musa Sayrami (1836–1917), who had occupied positions of importance in Aksu under both rebel regimes, authored Tārīkh-i amniyya (History of Peace), which is considered by modern historians as one of the most important historical sources on the period.[18]

Modern era

British Army officer Francis Younghusband visited Aksu in 1887 on his overland journey from Beijing to India. He described it as being the largest town he had seen on his way from the Chinese capital, with a population of about 20,000, besides other inhabitants of the district and a garrison of about 2,000 soldiers. "There were large bazaars and several inns—some for travellers, others for merchants wishing to make a prolonged stay to sell goods."[19]

In 1913, Aksu County (阿克蘇縣) was established.[20]

The Battle of Aksu (1933) occurred here on May 31, 1933.[21] Isma'il Beg, a Uighur, became the rebel Tao-yin of Aksu.[22] After the outbreak of the Ili Rebellion, the Ili National Army forces led by Abdulkerim Abbas attempting to take Aksu were repelled by National Revolutionary Army defenders commanded by Zhao Hanqi after two bitter sieges in September 1945.

On August 19, 1983, Aksu County became Aksu City (阿克苏市).[20][23] The city government began operation on May 7, 1984.[23]

Aksu was the site of a bombing in 2010.

On January 23, 2013, 802.733 km2 (309.937 sq mi) of territory was transferred from Aksu city to Aral city.[23]

Timeline

- Before 600 the region was under control of Huns and Uyghur Turkic tribes.

- 630: Xuanzang visited the kingdom.

- 800: Kuseen Uyghur kingdom was controlling the region.

- 1000: Qarakhanids Uyghur Empire started controlling the region.

- 1250: Chagatay Mongol started controlling the region.

- 1500: Yarkant Uyghur Empire started controlling the region.

Geography

Aksu City is divided into two non-contiguous areas. The northern area is inhabited and the southern area is in the Taklamakan Desert. The southern area ends at a strait line in the desert along the 39°28′57″N parallel that divides it from Lop County (Luopu) and Qira County (Cele) in Hotan Prefecture (Hetian).[24][25]

Neighbours

The kingdom bordered Kashgar to the south-west, and Kucha, Karasahr then Turpan to the east. Across the desert to the south was Khotan.

Climate

Aksu has a cold desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWk) with extreme seasonal variation in temperature. The monthly 24-hour average temperature ranges from −7.2 °C (19.0 °F) in January to 24.1 °C (75.4 °F), and the annual mean is 10.83 °C (51.5 °F). Precipitation totals only 80.6 mm (3.17 in) annually, and mostly falls in summer, as compared to an annual evaporation rate of about 1,200 to 1,500 mm (47 to 59 in); there are about 2,800−3,000 hours of bright sunshine annually. The frost-free period averages 200−220 days.

| Climate data for Aksu (1981−2010 normals, extremes 1971−2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

36.0 (96.8) |

37.4 (99.3) |

39.6 (103.3) |

38.6 (101.5) |

34.6 (94.3) |

29.4 (84.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

39.6 (103.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

5.3 (41.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

22.1 (71.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

0.8 (33.4) |

17.9 (64.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

10.9 (51.6) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

10.8 (51.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −12.3 (9.9) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

1.1 (34.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.2 (63.0) |

16.3 (61.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

4.7 (40.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.2 (−13.4) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

2.7 (36.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.7 (47.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−23.4 (−10.1) |

−25.2 (−13.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1.8 (0.07) |

2.7 (0.11) |

4.3 (0.17) |

3.8 (0.15) |

9.9 (0.39) |

12.6 (0.50) |

16.2 (0.64) |

12.1 (0.48) |

8.7 (0.34) |

4.7 (0.19) |

1.0 (0.04) |

2.8 (0.11) |

80.6 (3.19) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.3 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 5.3 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 35.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 59 | 49 | 41 | 45 | 48 | 53 | 56 | 61 | 63 | 68 | 74 | 57 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[26] Weather China | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

As of 2019, Aksu City included seven subdistricts, two towns, four townships and five other areas:[2][23][27]

Subdistricts (كوچا باشقارمىسى / 街道)

- Lengger Subdistrict (Langan; لەڭگەر كوچا باشقارمىسى / 栏杆街道), Yengibazar Subdistrict (Yingbazha; يېڭىبازار كوچا باشقارمىسى / 英巴扎街道), Qizil Kowruk Subdistrict (Hongqiao; قىزىل كۆۋرۈك كوچا باشقارمىسى / 红桥街道), Yengisheher Subdistrict (Xincheng; يېڭىشەھەر كوچا باشقارمىسى / 新城街道), Nancheng Subdistrict (جەنۇبىي شەھەر كوچا باشقارمىسى / 南城街道), Kokyar Subdistrict (Kekeya; كۆكيار كوچا باشقارمىسى / 柯柯牙街道), Dolan Subdistrict (Duolang; كۆكيار كوچا باشقارمىسى / 多浪街道)

Towns (بازىرى / 镇)

- Qaratal (Kara Tal,[28] Kaletale; قاراتال بازىرى[29] / 喀勒塔勒镇), Aykol[30] (Ayikule; ئايكۆل بازىرى / 阿依库勒镇)

Townships (يېزىسى / 乡)

- Egerchi Township (Igerchi,[31] Yiganqi; ئېگەرچى يېزىسى[32] / 依干其乡), Bextügman Township[33] (Baishitugeman, Beshtugmen; بەشتۈگمەن يېزىسى[34] / 拜什吐格曼乡), Topluq Township[35] (Tuopuluke; توپلۇق يېزىسى[36] / 托普鲁克乡), Qumbash Township (Kum Bash, Kumubaxi; قۇمباش يېزىسى[37] / 库木巴希乡), Tuokayi Township (托喀依乡)

Other areas

- Hongqipo Farm (红旗坡农场), Experimental Forestry Area (实验林场), Textile Factory City (纺织工业城), Economic and Technological Development Zone (经济技术开发区), Speciality Product Park (特色产业园区)

Economy

Industries in the city include textiles, construction, chemicals and others. Agricultural products include rice, wheat, corn and cotton. The local speciality is thin-shelled walnuts.[20]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 561,822 | — |

| 2010 | 535,657 | −0.48% |

| [23] | ||

Although the Tarim Basin is largely dominated by the Uyghurs, there are many Han Chinese in Aksu due to the presence of bingtuan state farms here.[38] The Chinese government had encouraged migration to Xinjiang from the late 1950s and early 1960s onwards, and by 1998, Han Chinese formed the majority in the urban area of Aksu. The population in 2015, 44.67% of the population was Han Chinese.[39]

In the 2000 census, a figure of 561,822 was recorded for the city's population. In the 2010 census figure, the population in the city of Aksu dropped slightly to 535,657.[40] The difference may be partly due to boundary changes.[41]

As of 2015, 278,210 of the 513,682 residents of the city were Uyghur, 226,781 were Han Chinese and 8,691 were from other ethnic groups.[42]

As of 1999, 57.89% of the population of Aksu City was Han Chinese and 40.75% of the population was Uyghur.[43]

Transportation

The county is served by the Southern Xinjiang Railway.

Notable people

- Dolkun Isa, President of the World Uyghur Congress

Historical maps

Historical English-language maps including Aksu:

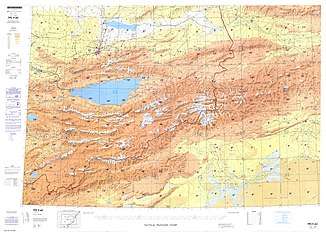

_-_panoramio.jpg) Map of Aksu (labeled as A-K'O-SU (AK SU YANGI SHAHR)) and surrounding region from the International Map of the World (AMS, 1950)[lower-alpha 1]

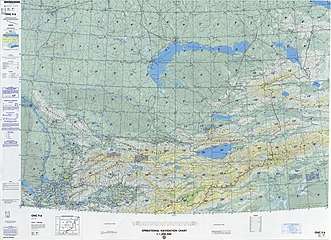

Map of Aksu (labeled as A-K'O-SU (AK SU YANGI SHAHR)) and surrounding region from the International Map of the World (AMS, 1950)[lower-alpha 1] Map including Aksu (DMA, 1981)

Map including Aksu (DMA, 1981) From the Operational Navigation Chart; map including Aksu (A-k'o-su) (DMA, 1985)[lower-alpha 2]

From the Operational Navigation Chart; map including Aksu (A-k'o-su) (DMA, 1985)[lower-alpha 2]

See also

Notes

- From map: "THE DELINEATION OF INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES ON THIS MAP MUST NOT BE CONSIDERED AUTHORITATIVE"

- From map: "The representation of international boundaries is not necessarily authoritative."

References

- Cox, W (2018). Demographia World Urban Areas. 14th Annual Edition (PDF). St. Louis: Demographia. p. 22.

- 阿克苏市概况. ئاقسۇ阿克苏市人民政府 (in Chinese). Retrieved 18 May 2020.

阿克苏市,维吾尔语意为“白水城”,{...}市辖4乡2镇、5个街道和8个片区管委会,

- Hill (2009), p. 408, n. 20.13. "In Buddhist Sanskrit, it was known as Bharuka."

- Bailey, H. W. (1985): Indo-Scythian Studies being Khotanese Texts Volume VII. Cambridge University Press. 1985.

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N. 1979. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty, p. 162. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-08-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bernard Samuel Myers (1959). Encyclopedia of World Art. McGraw-Hill. p. 445.

The city bearing the Turkish name of Aksu was perhaps earlier called Bharuka and may overlie the ancient site, of which nothing has yet been found.

- John E. Hill (July 2003). "Section 20 – The Kingdom of Suoche 莎車 (Yarkand).". Notes to The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu (2nd ed.). Washington University. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

Neolithic artefacts from 5000 BC have been discovered in the Aksu area. By the first century BC news had reached the Chinese imperial court of the Kingdom of Baluka, one of the 36 kingdoms of the Western Regions.

- Xuanzang. [Kingdom of Baluka]. Great Tang Records on the Western Regions (in Chinese). 1 – via Wikisource.

- Li, Rongxi. Translator. 1996. The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. Berkeley, California.

- Insight Guides (1 April 2017). Insight Guides Silk Road. APA. ISBN 978-1-78671-699-6.

- René Grousset (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

aksu 717.

- Jonathan Karam Skaff (6 August 2012). Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800. Oxford University Press. pp. 311–. ISBN 978-0-19-999627-8.

- Christopher I. Beckwith (28 March 1993). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power Among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese During the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 0-691-02469-3.

- Marvin C. Whiting (2002). Imperial Chinese Military History: 8000 BC-1912 AD. iUniverse. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-0-595-22134-9.

- Wright, George Frederick (2009), Asiatic Russia, Volume 1, BiblioBazaar, LLC, pp. 47–48, ISBN 978-1-110-26901-3 (Reprint of a 19th-century edition)

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1871). Accounts and papers of the House of Commons. Ordered to be printed. p. 34. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- Kim, Ho-dong (2004). Holy war in China: the Muslim rebellion and state in Chinese Central Asia, 1864–1877. Stanford University Press. p. xvi. ISBN 0-8047-4884-5.

- Younghusband, Francis E. (1896). The Heart of a Continent. London: John Murray. p. 154.

- 夏征农; 陈至立, eds. (September 2009). 辞海:第六版彩图本 [Cihai (Sixth Edition in Color)] (in Chinese). 上海. Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. p. 8. ISBN 9787532628599.

- Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 89. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 241. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- 阿克苏市历史沿革 [Aksu City Historical Development] (in Chinese). XZQH.org. 30 January 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- 阿克苏市概况. ئاقسۇ阿克苏市人民政府 (in Chinese). Retrieved 20 May 2020.

阿克苏市位于东经79°43′26″~82°00′38″,北纬39°28′57″~41°30′10″,

- 政府概况. 洛浦县政府网 Luopu County Government Network (in Chinese). Retrieved 18 December 2019.

地处东经79°59′-81°83′,北纬36°30′-39°29′东邻策勒县,{...}北伸延入塔克拉玛干大沙漠与阿克苏市、阿瓦提县为邻,

- ,中国气象数据网 - WeatherBk Data (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- 2019年统计用区划代码和城乡划分代码:阿克苏市 [2019 Statistical Area Numbers and Rural-Urban Area Numbers: Aksu City] (in Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China. 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

统计用区划代码 名称 652901001000 栏杆街道 652901002000 英巴扎街道 652901003000 红桥街道 652901004000 新城街道 652901005000 南城街道 652901006000 柯柯牙街道 652901007000 多浪街道 652901100000 喀勒塔勒镇 652901101000 阿依库勒镇 652901200000 依干其乡 652901201000 拜什吐格曼乡 652901202000 托普鲁克乡 652901203000 库木巴希乡 652901401000 红旗坡农场 652901404000 实验林场 652901407000 纺织工业城 652901408000 经济技术开发区 652901409000 特色产业园区

- "Meshrep". UNESCO. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

Folk Art Group of Culture Center of Kara Tal Town in Aksu City

- قۇربانجان قېيۇم, ed. (25 March 2019). ئاقسۇ ۋىلايەتلىك پارتكوم ئىشخانىسىنىڭ كادىرلىرى ئۆيمۇ ئۆي كىرىپ پارتىيەنىڭ خەلققە نەپ يەتكۈزۈش سىياسەتلىرىنى تەشۋىق قىلدى. Tianshannet (in Uyghur). Retrieved 19 May 2020.

ئاقسۇ شەھىرى قاراتال بازىرى

- "Congressional-Executive Commission on China". p. 165 – via Google Books.

Aykol township, Aksu city, Aksu prefecture

- "China: List of Political Prisoners Detained or Imprisoned as of October 10, 2012" (PDF). Congressional-Executive Commission on China. 10 October 2012. p. 77. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

Yiganchi (Igerchi)

- دۇ ۋەنگۈي ئاقسۇ شەھىرىدە تەكشۈرۈپ تەتقىق قىلغاندا، مۇنداق تەكىتلىدى: دىققەتنى باش نىشانغا مەركەزلەشتۈرۈپ، تۈرلۈك خىزمەتلەرنى چوڭقۇر، ئىنچىكە، ئەمەلىي ئىشلەش كېرەك. 5 July 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

ئاقسۇ شەھىرىنىڭ ئېگەرچى يېزىسى

- Xie Yuzhong 解玉忠 (2003). 地名中的新疆 (in Chinese). Ürümqi: 新疆人民出版社. pp. 161–163. ISBN 7-228-08004-1.

依干其 Igarchi {...}

}

拜什吐格曼 Bextügman {...}

托普鲁克 Topluk {... - 古丽米娜, ed. (7 November 2018). ئاقسۇ شەھىرىدە خىزمەت ئەترىتىدىكىلەر كەنت ئاھالىسىگە ياردەملىشىپ ئۈندىداردا غاز سېتىشىپ بەردى. ﺷﯩﻨﺠﺎﯓ ﻛﯘﺋﯧﻨﻠﯘﻥ ﺗﻮﺭﻯ & Tianshannet (in Uyghur). Retrieved 19 May 2020.

ئاقسۇ شەھىرى بەشتۈگمەن يېزىسى

- Shohret Hoshur, Joshua Lipes (23 August 2010). "More Arrests in Aksu Blast". Radio Free Asia. Translated by Shohret Tursun, Luisetta Mudie. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

According to a staff member from the Topluq police station, officers have been searching all area hospitals, walk-in clinics, and public spaces in the vicinity of the village.

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ئامانگۈل ئابدۇراخمان, ed. (19 March 2020). ئېتىز - ئېرىق باشلىرىدا ئالدىراشچىلىق باشلاندى. Xinjiang Daily (in Uyghur). Retrieved 19 May 2020.

ئاقسۇ شەھىرىنىڭ توپلۇق يېزىسى

- ئالىم راخمان, ed. (21 March 2016). خىزمەت گۇرۇپپىسى دېھقانلارغا بازار ئېچىپ بەردى. People's Daily (in Uyghur). Retrieved 19 May 2020.

ئاقسۇ شەھىرى قۇمباش يېزىسى

- Stanley W. Toops (15 March 2004). "The Demography of Xinjiang". In S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. Routledge. p. 254. ISBN 978-0765613189.

- Stanley W. Toops (15 March 2004). "The Demography of Xinjiang". In S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. Routledge. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-0765613189.

- "Largest Cities in China 2016". Country Digest.

- "ĀKÈSŪ SHÌ (County-level City)". City Population.

- 3-7 各地、州、市、县(市)分民族人口数 (in Chinese). شىنجاڭ ئۇيغۇر ئاپتونوم رايونى 新疆维吾尔自治区统计局 Statistic Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Morris Rossabi, ed. (2004). Governing China’s Multiethnic Frontiers (PDF). University of Washington Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-295-98390-6.

Further reading

- Aksu City Historical Annals Editing Committee 阿克苏市史志编纂委员会 ed. (1991) Aksu City Annals. 阿克苏市志. Xinhua. ISBN 7-5011-1531-1

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Puri, B. N. Buddhism in Central Asia, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited, Delhi, 1987. (2000 reprint).

- Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols. Clarendon Press. Oxford.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1921. Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 5 vols. London & Oxford. Clarendon Press. Reprint: Delhi. Motilal Banarsidass. 1980.

- Yu, Taishan. 2004. A History of the Relationships between the Western and Eastern Han, Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties and the Western Regions. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 131 March, 2004. Dept. of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania.

- The History of the Western Han records some information about the kingdom.

- Either the Old Book of Tang or the New Book of Tang records Xuanzang's information and a little extra.

External links

- Silk Road Seattle - University of Washington (The Silk Road Seattle website contains many useful resources including a number of full-text historical works)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aksu City. |