São Paulo

São Paulo (/ˌsaʊ ˈpaʊloʊ/; Portuguese pronunciation: [sɐ̃w̃ ˈpawlu] (![]()

São Paulo | |

|---|---|

| Município de São Paulo Municipality of São Paulo | |

From the top, clockwise: São Paulo Cathedral and the See Square; overview of the historic downtown from Copan Building; Monument to the Bandeiras at the entrance of Ibirapuera Park; São Paulo Museum of Art on Paulista Avenue; Ipiranga Museum at the Independence Park; and Octávio Frias de Oliveira Bridge over the Marginal Pinheiros. | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): Terra da Garoa (Land of Drizzle); Sampa; "Pauliceia" | |

| Motto(s): | |

Location in the state of São Paulo | |

São Paulo Location in Brazil  São Paulo São Paulo (South America) | |

| Coordinates: 23°33′S 46°38′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | January 25, 1554 |

| Named for | Paul the Apostle |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Bruno Covas[1] (PSDB) |

| • Vice Mayor | Vacant |

| Area | |

| • Megacity | 1,521.11 km2 (587.3039 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 11,698 km2 (4,517 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 7,946.96 km2 (3,068.338 sq mi) |

| • Macrometropolis | 53,369.61 km2 (20,606.12 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 760 m (2,493.4 ft) |

| Population | 12,176,866 |

| • Rank | 1st in Brazil |

| • Density | 8,005.25/km2 (20,733.5/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 12,176,866 |

| • Metro | 21,571,281[4] (Greater São Paulo) |

| • Metro density | 2,714.45/km2 (7,030.4/sq mi) |

| • Macrometropolis | 33,652,991 [5] |

| Demonym(s) | Portuguese: paulistano |

| Time zone | UTC−03:00 (BRT) |

| Postal Code (CEP) | 01000-000 |

| Area code(s) | +55 11 |

| HDI (2016) | 0.843 [6] very high - 1st |

| PPP 2018 | US$687 billion [7] 1st |

| Per Capita | US$56,418 [7] 1st |

| Nominal 2018 | US$274 billion [7] 1st |

| Per Capita | US$22,502[7] 1st |

| Website | São Paulo, SP |

Having the largest economy by GDP in Latin America and the Southern Hemisphere,[11] the city is home to the São Paulo Stock Exchange. Paulista Avenue is the economic core of São Paulo. The city has the 11th largest GDP in the world,[12] representing alone 10.7% of all Brazilian GDP[13] and 36% of the production of goods and services in the state of São Paulo, being home to 63% of established multinationals in Brazil,[14] and has been responsible for 28% of the national scientific production in 2005.[15]

The metropolis is also home to several of the tallest skyscrapers in Brazil, including the Mirante do Vale, Edifício Itália, Banespa, North Tower and many others. The city has cultural, economic and political influence both nationally and internationally. It is home to monuments, parks and museums such as the Latin American Memorial, the Ibirapuera Park, Museum of Ipiranga, São Paulo Museum of Art, and the Museum of the Portuguese Language. The city holds events like the São Paulo Jazz Festival, São Paulo Art Biennial, the Brazilian Grand Prix, São Paulo Fashion Week, the ATP Brasil Open, the Brasil Game Show and the Comic Con Experience. The São Paulo Gay Pride Parade rivals the New York City Pride March as the largest gay pride parade in the world.[16][17]

São Paulo is a cosmopolitan, melting pot city, home to the largest Arab, Italian, Japanese, and Portuguese diasporas, with examples including ethnic neighborhoods of Mercado, Bixiga, and Liberdade respectively. São Paulo is also home to the largest Jewish population in Brazil, with about 75,000 Jews.[18] In 2016, inhabitants of the city were native to over 200 different countries.[19] People from the city are known as paulistanos, while paulistas designates anyone from the state, including the paulistanos. The city's Latin motto, which it has shared with the battleship and the aircraft carrier named after it, is Non ducor, duco, which translates as "I am not led, I lead."[20] The city, which is also colloquially known as Sampa or Terra da Garoa (Land of Drizzle), is known for its unreliable weather, the size of its helicopter fleet, its architecture, gastronomy, severe traffic congestion and skyscrapers. São Paulo was one of the host cities of the 1950 and the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Additionally, the city hosted the IV Pan American Games and the São Paulo Indy 300.

History

Early Indigenous Period

The region of modern-day São Paulo, then known as Piratininga plains around the Tietê River, was inhabited by the Tupi people, such as the Tupiniquim, Guaianas, and Guarani. Other tribes also lived in areas that today form the metropolitan region.

The region was divided in Caciquedoms (chiefdoms) at the time of encounter with the Europeans. The most notable Cacique was Tibiriça, known for his support for the Portuguese and other European colonists. Among the many indigenous names that survive today are Tietê, Ipiranga, Tamanduateí, Anhangabaú, Piratininga, Itaquaquecetuba, Cotia, Itapevi, Barueri, Embu-Guaçu etc...

Colonial period

The Portuguese village of São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga was marked by the founding of the Colégio de São Paulo de Piratininga on January 25, 1554. The Jesuit college of twelve priests included Manuel da Nóbrega and Spanish priest José de Anchieta. They built a mission on top of a steep hill between the Anhangabaú and Tamanduateí rivers.[21]

They first had a small structure built of rammed earth, made by American Indian workers in their traditional style. The priests wanted to evangelize the Indians who lived in the Plateau region of Piratininga and convert them to Christianity. The site was separated from the coast by the Serra do Mar mountain range, called by the Indians "Serra Paranapiacaba."

The college was named for a Christian saint and its founding on the feast day of the celebration of the conversion of the Apostle Paul of Tarsus. Father José de Anchieta wrote this account in a letter to the Society of Jesus:

The settlement of the region's Courtyard of the College began in 1560. During the visit of Mem de Sá, Governor-General of Brazil, the Captaincy of São Vicente, he ordered the transfer of the population of the Village of Santo André da Borda do Campo to the vicinity of the college. It was then named "College of St. Paul Piratininga". The new location was on a steep hill adjacent to a large wetland, the lowland do Carmo. It offered better protection from attacks by local Indian groups. It was renamed Vila de São Paulo, belonging to the Captaincy of São Vicente.

For the next two centuries, São Paulo developed as a poor and isolated village that survived largely through the cultivation of subsistence crops by the labor of natives. For a long time, São Paulo was the only village in Brazil's interior, as travel was too difficult for many to reach the area. Mem de Sá forbade colonists to use the "Path Piraiquê" (Piaçaguera today), because of frequent Indian raids along it.

On March 22, 1681, the Marquis de Cascais, the donee of the Captaincy of São Vicente, moved the capital to the village of St. Paul, designating it the "Head of the captaincy". The new capital was established on April 23, 1683, with public celebrations.

The Bandeirantes

In the 17th century, São Paulo was one of the poorest regions of the Portuguese colony. It was also the center of interior colonial development. Because they were extremely poor, the Paulistas could not afford to buy African slaves, as did other Portuguese colonists. The discovery of gold in the region of Minas Gerais, in the 1690s, brought attention and new settlers to São Paulo. The Captaincy of São Paulo and Minas do Ouro was created on November 3, 1709, when the Portuguese crown purchased the Captaincies of São Paulo and Santo Amaro from the former grantees.

Conveniently located in the country, up the steep Serra do Mar sea ridge when traveling from Santos, while also not too far from the coastline, São Paulo became a safe place to stay for tired travelers. The town became a center for the bandeirantes, intrepid explorers who marched into unknown lands in search for gold, diamonds, precious stones, and Indians to enslave.

The bandeirantes, which could be translated as "flag-bearers" or "flag-followers", organized excursions into the land with the primary purpose of profit and the expansion of territory for the Portuguese crown. Trade grew from the local markets and from providing food and accommodation for explorers. The bandeirantes eventually became politically powerful as a group, and forced the expulsion of the Jesuits from the city of São Paulo in 1640. The two groups had frequently come into conflict because of the Jesuits' opposition to the domestic slave trade in Indians.

On July 11, 1711, the town of São Paulo was elevated to city status. Around the 1720s, gold was found by the pioneers in the regions near what are now Cuiabá and Goiania. The Portuguese expanded their Brazilian territory beyond the Tordesillas Line to incorporate the gold regions.

When the gold ran out in the late 18th century, São Paulo shifted to growing sugar cane. Cultivation of this commodity crop spread through the interior of the Captaincy. The sugar was exported through the Port of Santos. At that time, the first modern highway between São Paulo and the coast was constructed and named the Walk of Lorraine.

Nowadays, the estate that is home to the Governor of the State of São Paulo, located in the city of São Paulo, is called the Palácio dos Bandeirantes (Palace of Bandeirantes), in the neighborhood of Morumbi.

Imperial Period

After Brazil became independent from Portugal in 1822, as declared by Emperor Pedro I where the Monument of Ipiranga is located, he named São Paulo as an Imperial City. In 1827, a law school was founded at the Convent of São Francisco, today part of the University of São Paulo. The influx of students and teachers gave a new impetus to the city's growth, thanks to which the city became the Imperial City and Borough of Students of St. Paul of Piratininga.

The expansion of coffee production was a major factor in the growth of São Paulo, as it became the region's chief export crop and yielded good revenue. It was cultivated initially in the Vale do Paraíba (Paraíba Valley) region in the East of the State of São Paulo, and later on in the regions of Campinas, Rio Claro, São Carlos and Ribeirão Preto.

From 1869 onward, São Paulo was connected to the port of Santos by the Railroad Santos-Jundiaí, nicknamed The Lady. In the late 19th century, several other railroads connected the interior to the state capital. São Paulo became the point of convergence of all railroads from the interior of the state. Coffee was the economic engine for major economic and population growth in the State of São Paulo.

In 1888, the "Golden Law" (Lei Áurea) was sanctioned by Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil, abolishing the institution of slavery in Brazil. Slaves were the main source of labor in the coffee plantations until then. As a consequence of this law, and following governmental stimulus towards the increase of immigration, the province began to receive a large number of immigrants, largely Italians, Japanese and Portuguese peasants, many of whom settled in the capital. The region's first industries also began to emerge, providing jobs to the newcomers, especially those who had to learn Portuguese.

Old Republican Period

By the time Brazil became a republic on November 15, 1889, coffee exports were still an important part of São Paulo's economy. São Paulo grew strong in the national political scene, taking turns with the also rich state of Minas Gerais in electing Brazilian presidents, an alliance that became known as "coffee and milk", given that Minas Gerais was famous for its dairy produce.

During this period, São Paulo went from regional center to national metropolis, becoming industrialized and reaching its first million inhabitants in 1928. Its greatest growth in this period was relative in the 1890s when it doubled its population. The height of the coffee period is represented by the construction of the second Estação da Luz (the present building) at the end of the 19th century and by the Paulista Avenue in 1900, where they built many mansions.[22]

Industrialization was the economic cycle that followed the coffee plantation model. By the hands of some industrious families, including many immigrants of Italian and Jewish origin, factories began to arise and São Paulo became known for its smoky, foggy air. The cultural scene followed modernist and naturalist tendencies in fashion at the beginning of the 20th century. Some examples of notable modernist artists are poets Mário de Andrade and Oswald de Andrade, artists Anita Malfatti, Tarsila do Amaral and Lasar Segall, and sculptor Victor Brecheret. The Modern Art Week of 1922 that took place at the Theatro Municipal was an event marked by avant-garde ideas and works of art. In 1929, São Paulo won its first skyscraper, the Martinelli Building.[22]

The modifications made in the city by Antônio da Silva Prado, Baron of Duprat and Washington Luiz, who governed from 1899 to 1919, contributed to the climate Development of the city; Some scholars consider that the entire city was demolished and rebuilt at that time.

São Paulo's main economic activities derive from the services industry – factories are since long gone, and in came financial services institutions, law firms, consulting firms. Old factory buildings and warehouses still dot the landscape in neighborhoods such as Barra Funda and Brás. Some cities around São Paulo, such as Diadema, São Bernardo do Campo, Santo André, and Cubatão are still heavily industrialized to the present day, with factories producing from cosmetics to chemicals to automobiles.

Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932

This "revolution" is considered by some historians as the last armed conflict to take place in Brazil's history. On July 9, 1932, the population of São Paulo town rose against a coup d'état by Getúlio Vargas to take the presidential office. The movement grew out of local resentment from the fact that Vargas ruled by decree, unbound by a constitution, in a provisional government. The 1930 coup also affected São Paulo by eroding the autonomy that states enjoyed during the term of the 1891 Constitution and preventing the inauguration of the governor of São Paulo Júlio Prestes in the Presidency of the Republic, while simultaneously overthrowing President Washington Luís, who was governor of São Paulo from 1920 to 1924. These events marked the end of the Old Republic.

The uprising commenced on July 9, 1932, after four protesting students were killed by federal government troops on May 23, 1932. On the wake of their deaths, a movement called MMDC (from the initials of the names of each of the four students killed, Martins, Miragaia, Dráusio and Camargo) started. A fifth victim, Alvarenga, was also shot that night, but died months later.

In a few months, the state of São Paulo rebelled against the federal government. Counting on the solidarity of the political elites of two other powerful states, (Minas Gerais and Rio Grande do Sul), the politicians from São Paulo expected a quick war. However, that solidarity was never translated into actual support, and the São Paulo revolt was militarily crushed on October 2, 1932.

In total, there were 87 days of fighting (July 9 to October 4, 1932 – with the last two days after the surrender of São Paulo), with a balance of 934 official deaths, though non-official estimates report up to 2,200 dead, and many cities in the state of São Paulo suffered damage due to fighting.

There is an obelisk in front of Ibirapuera Park that serves as a memorial to the young men that died for the MMDC. The University of São Paulo's Law School also pays homage to the students that died during this period with plaques hung on its arcades.

Geography

São Paulo is located in Southeastern Brazil, in southeastern São Paulo State, approximately halfway between Curitiba and Rio de Janeiro. The city is located on a plateau located beyond the Serra do Mar (Portuguese for "Sea Range" or "Coastal Range"), itself a component of the vast region known as the Brazilian Highlands, with an average elevation of around 799 metres (2,621 ft) above sea level, although being at a distance of only about 70 kilometres (43 mi) from the Atlantic Ocean. The distance is covered by two highways, the Anchieta and the Imigrantes, (see "Transportation" below) that roll down the range, leading to the port city of Santos and the beach resort of Guarujá. Rolling terrain prevails within the urbanized areas of São Paulo except in its northern area, where the Serra da Cantareira Range reaches a higher elevation and a sizable remnant of the Atlantic Rain Forest. The region is seismically stable and no significant seismic activity has ever been recorded.[24]

Metropolitan area

The nonspecific term "Grande São Paulo" ("Greater São Paulo") covers multiple definitions. The legally defined Região Metropolitana de São Paulo consists of 39 municipalities in total and a population of 21.1 million[25] inhabitants (as of the 2014 National Census).

The Metropolitan Region of São Paulo is known as the financial, economic, and cultural center of Brazil. The largest municipalities are Guarulhos with a population of more than 1 million people, plus several municipalities with more than 100,000 inhabitants, such as São Bernardo do Campo (811,000 inh.) and Santo André (707,000 inh.) in the ABC Region. The ABC Region in the south of Grande São Paulo is an important location for industrial corporations, such as Volkswagen and Ford Motors.[26]

Because São Paulo has urban sprawl, it uses a different definition for its metropolitan area called Expanded Metropolitan Complex of São Paulo. Analogous to the BosWash definition, it is one of the largest urban agglomerations in the world, with 32 million inhabitants,[27] behind Tokyo, which includes 4 contiguous legally defined metropolitan regions and 3 micro-regions.

Hydrography

The Tietê River and its tributary, the Pinheiros River, were once important sources of fresh water and leisure for São Paulo. However, heavy industrial effluents and wastewater discharges in the later 20th century caused the rivers to become heavily polluted. A substantial clean-up program for both rivers is underway, financed through a partnership between local government and international development banks such as the Japan Bank for International Cooperation. Neither river is navigable in the stretch that flows through the city, although water transportation becomes increasingly important on the Tietê river further downstream (near river Paraná), as the river is part of the River Plate basin.[28]

No large natural lakes exist in the region, but the Billings and Guarapiranga reservoirs in the city's southern outskirts are used for power generation, water storage and leisure activities, such as sailing. The original flora consisted mainly of broadleaf evergreens. Non-native species are common, as the mild climate and abundant rainfall permit a multitude of tropical, subtropical and temperate plants to be cultivated, especially the ubiquitous eucalyptus.[29]

The north of the municipality contains part of the 7,917 hectares (19,560 acres) Cantareira State Park, created in 1962, which protects a large part of the metropolitan São Paulo water supply.[30] In 2015, São Paulo experienced a major drought, which led several cities in the state to start a rationing system.[31]

Climate

According to the Köppen classification, the city has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa).[32][33] In summer (January through March), the mean low temperature is about 19 °C (66 °F) and the mean high temperatures is near 28 °C (82 °F). In winter, temperatures tend to range between 12 and 22 °C (54 and 72 °F).

The record high temperature was 37.8 °C (100.0 °F) on October 17, 2014[34] and the lowest −3.2 °C (26.2 °F) on June 25, 1918.[35][36] The Tropic of Capricorn, at about 23°27' S, passes through north of São Paulo and roughly marks the boundary between the tropical and temperate areas of South America. Because of its elevation, however, São Paulo experiences a more temperate climate.[37]

The city experiences four seasons. The summer is warm and rainy. Autumn and spring are transitional seasons. Winter is the most cold season, with cloudiness around town and frequently polar air masses. Frosts occur sporadically in regions further away from the center, in some winters throughout the city. Regions further away from the center and in cities in the metropolitan area, can reach temperatures next to 0 °C (32 °F), or even lower in the winter.

Rainfall is abundant, annually averaging 1,454 millimetres (57.2 in).[39] It is especially common in the warmer months averaging 219 millimetres (8.6 in) and decreases in winter, averaging 47 millimetres (1.9 in). Neither São Paulo nor the nearby coast has ever been hit by a tropical cyclone and tornadic activity is uncommon. During late winter, especially August, the city experiences the phenomenon known as "veranico" or "verãozinho" ("little summer"), which consists of hot and dry weather, sometimes reaching temperatures well above 28 °C (82 °F). On the other hand, relatively cool days during summer are fairly common when persistent winds blow from the ocean. On such occasions daily high temperatures may not surpass 20 °C (68 °F), accompanied by lows often below 15 °C (59 °F), however, summer can be extremely hot when a heat wave hits the city followed by temperatures around 34 °C (93 °F), but in places with greater skyscraper density and less tree cover, the temperature can feel like 39 °C (102 °F), as on Paulista Avenue for example. In the summer of 2014, São Paulo was affected by a heat wave that lasted for almost 4 weeks with highs above 30 °C (86 °F), peeking on 36 °C (97 °F). Secondary to deforestation, groundwater pollution, and climate change, São Paulo is increasingly susceptible to drought and water shortages.[40]

.jpg)

Due to the altitude of the city, there are only few hot nights in São Paulo even in the summer months, with minimum temperatures rarely exceeding 21 °C (70 °F). In winter, however, the strong inflow of cold fronts accompanied by excessive cloudiness and polar air cause very low temperatures, even in the afternoon.

Afternoons with maximum temperatures ranging between 13 and 15 °C (55 and 59 °F) are common even during the fall and early spring. During the winter, there have been several recent records of cold afternoons, as on July 24, 2013 in which the maximum temperature was 8 °C (46 °F) and the wind chill hit 0 °C (32 °F) during the afternoon.

São Paulo is known for its rapidly changing weather. Locals say that all four seasons can be experienced in one day, similar to Melbourne, Australia. In the morning, when winds blow from the ocean, the weather can be cool or sometimes even cold. When the sun hits its peak, the weather can be extremely dry and hot. When the sun sets, the cold wind comes back bringing cool temperatures. This phenomenon happens usually in the winter.

| Climate data for São Paulo (Mirante de Santana, 1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37.0 (98.6) |

36.4 (97.5) |

34.3 (93.7) |

33.4 (92.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

28.8 (83.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

37.8 (100.0) |

36.3 (97.3) |

35.6 (96.1) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 32.8 (91.0) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.3 (90.1) |

30.5 (86.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

27.2 (81.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

30.5 (86.9) |

32.3 (90.1) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.4 (90.3) |

34.3 (93.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28.2 (82.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

25.7 (78.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 22.9 (73.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.6 (61.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 19.3 (66.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

12.3 (54.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 16.3 (61.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 11.9 (53.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.4 (41.7) |

1.2 (34.2) |

0.8 (33.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

5.7 (42.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 288.2 (11.35) |

246.2 (9.69) |

214.5 (8.44) |

82.1 (3.23) |

78.1 (3.07) |

50.3 (1.98) |

47.8 (1.88) |

36.0 (1.42) |

84.8 (3.34) |

126.6 (4.98) |

136.6 (5.38) |

224.4 (8.83) |

1,618.7 (63.73) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 15 | 14 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 107 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 79 | 78 | 77 | 74 | 77 | 79 | 78 | 80 | 78.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 170.6 | 162.2 | 167.1 | 165.8 | 182.3 | 172.6 | 187.1 | 175.3 | 152.6 | 153.9 | 163.0 | 150.8 | 2,003.3 |

| Source: Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (INMET).[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for São Paulo (Horto Florestal, 1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.6 (94.3) |

35.8 (96.4) |

33.4 (92.1) |

32.0 (89.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.0 (84.2) |

33.2 (91.8) |

35.2 (95.4) |

34.3 (93.7) |

34.6 (94.3) |

33.9 (93.0) |

35.8 (96.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.3 (81.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.2 (70.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

16.4 (61.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.6 (65.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 16.6 (61.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

14.1 (57.4) |

11.7 (53.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

9.7 (49.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

13.7 (56.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

0.2 (32.4) |

0.4 (32.7) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.7 (42.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 245.6 (9.67) |

243.8 (9.60) |

159.2 (6.27) |

76.0 (2.99) |

59.7 (2.35) |

58.7 (2.31) |

53.1 (2.09) |

39.9 (1.57) |

76.2 (3.00) |

162.7 (6.41) |

195.7 (7.70) |

220.6 (8.69) |

1,591.3 (62.65) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 16 | 14 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 15 | 113 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 80.4 | 80.3 | 81.2 | 80.5 | 79.2 | 77.4 | 74.6 | 76.2 | 79.3 | 79.4 | 80.4 | 79.2 |

| Source: Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (INMET).[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

In 2013, São Paulo was the most populous city in Brazil and in South America.[50] According to the 2010 IBGE Census, there were 11,244,369 people residing in the city of São Paulo.[51] The census found 6,824,668 White people (60.6%), 3,433,218 Pardo (multiracial) people (30.5%), 736,083 Black people (6.5%), 246,244 Asian people (2.2%) and 21,318 Amerindian people (0.2%).[52]

In 2010, the city had 2,146,077 opposite-sex couples and 7,532 same-sex couples. The population of São Paulo was 52.6% female and 47.4% male.[52]

Immigration

São Paulo is considered the most multicultural city in Brazil. Since 1870 to 2010, approximately 2.3 million immigrants arrived in the state, from all parts of the world. The Italian community is one of the strongest, with a presence throughout the city. Of the 9 million inhabitants of São Paulo, 50% (4.5 million people) have full or partial Italian ancestry. São Paulo has more descendants of Italians than any Italian city (the largest city of Italy is Rome, with 2.5 million inhabitants).[53]

Even today, Italians are grouped in neighborhoods like Bixiga, Brás, and Mooca to promote celebrations and festivals. In the early twentieth century, the Italian and the dialects were spoken almost as much as the Portuguese in the city, which influenced the formation of the São Paulo dialect of today. Six thousand pizzerias are producing about a million pizzas a day. Brazil has the largest Italian population outside Italy, with São Paulo being the most populous city with Italian ancestry in the world.[54]

The Portuguese community is also large, and it is estimated that three million paulistanos have some origin in Portugal. The Jewish colony is more than 60,000 people in São Paulo and is concentrated mainly in Higienópolis and Bom Retiro.[55]

From the nineteenth century through the first half of the twentieth century, São Paulo also received German immigrants (in the current neighborhood of Santo Amaro), Spanish and Lithuanian (in the neighborhood Vila Zelina).[55]

São Paulo is not only home to the largest Japanese diaspora – over 1.5 million Japanese descendants live in São Paulo – but it also has over 600 Japanese restaurants (20% more than "churrascarias" – Brazilian steakhouses) where more than 12 millions sushis are sold every month.

| Immigrants | Percentage of immigrants in foreign born population[56] |

|---|---|

| Italians | 47.9% |

| Portuguese | 29.3% |

| Germans | 9.9% |

| Spaniards | 3.2% |

A French observer, travelling to São Paulo at the time, noted that there was a division of the capitalist class, by nationality (...) Germans, French and Italians shared the dry goods sector with Brazilians. Foodstuffs was generally the province of either Portuguese or Brazilians, except for bakery and pastry which was the domain of the French and Germans. Shoes and tinware were mostly controlled by Italians. However, the larger metallurgical plants were in the hands of the English and the Americans. (...) Italians outnumbered Brazilians two to one in São Paulo.[57]

Until 1920, 1,078,437 Italians entered in the State of São Paulo. Of the immigrants who arrived there between 1887 and 1902, 63.5% came from Italy. Between 1888 and 1919, 44.7% of the immigrants were Italians, 19.2% were Spaniards and 15.4% were Portuguese.[58] In 1920, nearly 80% of São Paulo city's population was composed of immigrants and their descendants and Italians made up over half of its male population.[58] At that time, the Governor of São Paulo said that "if the owner of each house in São Paulo display the flag of the country of origin on the roof, from above São Paulo would look like an Italian city". In 1900, a columnist who was absent from São Paulo for 20 years wrote "then São Paulo used to be a genuine Paulista city, today it is an Italian city."[58]

| Year | Italians | Percentage of the city[58] |

|---|---|---|

| 1886 | 5,717 | 13% |

| 1893 | 45,457 | 35% |

| 1900 | 75,000 | 31% |

| 1910 | 130,000 | 33% |

| 1916 | 187,540 | 37% |

Research conducted by the University of São Paulo (USP) shows the city's high ethnic diversity: when asked if they are "descendants of foreign immigrants", 81% of the students reported "yes". The main reported ancestries were: Italian (30.5%), Portuguese (23%), Spanish (14%), Japanese (8%), German (6%), Brazilian (4%), African (3%), Arab (2%) and Jewish (1%).[59]

The city once attracted numerous immigrants from all over Brazil and even from foreign countries, due to a strong economy and for being the hub of most Brazilian companies.[60]

Domestic migration

Since the 19th century people began migrating from northeastern Brazil into São Paulo. This migration grew enormously in the 1930s and remained huge in the next decades. The concentration of land, modernization in rural areas, changes in work relationships and cycles of droughts stimulated migration. Northeastern migrants live mainly in hazardous and unhealthy areas of the city, in cortiços, in slums (favelas) of the metropolis, because they offer cheaper housing. The largest concentration of northeastern migrants was found in the area of Sé/Brás (districts of Brás, Bom Retiro, Cambuci, Pari and Sé). In this area they composed 41% of the population.[61]

[62] The main groups, considering all the metropolitan area, are: 6 million people of Italian descent,[63] 3 million people of Portuguese descent,[64] 1.7 million people of African descent,[65] 1 million people of Arab descent,[66] 665,000 people of Japanese descent,[66] 400,000 people of German descent,[66] 250,000 people of French descent,[66] 150,000 people of Greek descent,[66] 120,000 people of Chinese descent,[66] 120,000–300,000 Bolivian immigrants,[67] 50,000 people of Korean descent,[68] and 40,000 Jews.[69]

São Paulo is also receiving waves of immigration from Haiti and from many countries of Africa and the Caribbean. Those immigrants are mainly concentrated in Praca da Sé, Glicério and Vale do Anhangabaú in the Central Zone of São Paulo.

Religion

.jpg)

Like the cultural variety verifiable in São Paulo, there are several religious manifestations present in the city. Although it has developed on an eminently Catholic social matrix, both due to colonization and immigration – and even today most of the people of São Paulo declare themselves Roman Catholic – it is possible to find in the city dozens of different Protestant denominations, as well as the practice of Islam, Spiritism, among others. Buddhism and Eastern religions also have relevance among the beliefs most practiced by Paulistanos. It is estimated that there are more than one hundred thousand Buddhist followers and Hindu. Also considerable are Judaism, Mormonism and Afro-Brazilian religions.

According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), in 2010 the population of São Paulo was 6,549,775 Roman Catholics (58.2%), 2,887,810 Protestants (22.1%), 531,822 Spiritists (4.7 percent), 101,493 Jehovah's Witnesses (0.9 percent), 75,075 Buddhists (0.7 percent), 50,794 Umbandists (0.5 percent), 43,610 Jews (0.4 percent), 28,673 Catholic Apostolic Brazilians (0.3%), 25,583 eastern religious (0.2%), 18,058 candomblecists (0.2%), 17,321 Mormons (0.2%), 14,894 Orthodox Catholics (0.1%), 9,119 spiritualists (0.1%), 8,277 Muslims (0.1%), 7,139 esoteric (0.1%), 1,829 practiced Indian traditions (<0.1%) and 1,008 were Hindu (<0.1%). Others 1,056 008 had no religion (9.4%), 149,628 followed other Christian religiosities (1.3%), 55,978 had an undetermined religion or multiple belonging (0.5%), 14,127 did not know (0.1%) And 1,896 reported following other religiosities (<0.1%).

The Roman Catholic Church divides the territory of the municipality of São Paulo into four ecclesiastical circumscriptions: the Archdiocese of São Paulo, and the adjacent Diocese of Santo Amaro, the Diocese of São Miguel Paulista and the Diocese of Campo Limpo, the last three suffragans of the first. The archive of the archdiocese, called the Metropolitan Archival Dom Duarte Leopoldo e Silva, located in the Ipiranga neighborhood, holds one of the most important documentary heritage in Brazil. The archiepiscopal is the Metropolitan Cathedral of São Paulo (known as Sé Cathedral), located in Praça da Sé, considered one of the five largest Gothic temples in the world. The Roman Catholic Church recognizes as patron saints of the city Saint Paul of Tarsus and Our Lady of Penha of France.

The city has the most diverse Protestant or Reformed creeds, such as the Evangelical Community of Our Land, Maranatha Christian Church, Lutheran Church, Presbyterian Church, Methodist Church, Anglican Episcopal Church, Baptist churches, Assembly Church of God, The Seventh-day Adventist Church, the World Church of God's Power, the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, the Christian Congregation in Brazil, among others, as well as Christians of various denominations.

Public security

According to the 2011 Global Homicide Survey released by the United Nations, in the period between 2004 and 2009 the homicide rate dropped from 20.8 to 10.8 murders per 100,000 inhabitants. The UN pointed to São Paulo as an example of how big cities can reduce crime. Crime rates, such as homicide, have been steadily declining for 8 years. The number of murders in 2007 was 63% lower than in 1999. Carandiru's 9th DP is considered one of the five best police stations in the world and the best in Latin America.

In 2008, the city of São Paulo ranked 493rd in the list of the most violent cities in Brazil. Among the capitals, it was the fourth less violent, registering, in 2006, homicide rates higher than those of Boa Vista, Palmas and Natal.

In a survey on the Adolescent Homicide Index (IHA), released in 2009, São Paulo ranked 151st among 267 cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants. In November 2009, the Ministry of Justice and the Brazilian Forum of Public Security published a survey that pointed to São Paulo as the safest Brazilian capital for young people. Between 2000 and 2010, the city of São Paulo reduced its homicide rate by 78%. According to data from the Map of Violence 2011, published by the Sangari Institute and the Ministry of Justice, the city of São Paulo has the lowest homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants among all Brazilian capitals.

Social challenges

Since the beginning of the 20th century, São Paulo has been a major economic center in Latin America. During two World Wars and the Great Depression, coffee exports (from other regions of the state) were critically affected. This led wealthy coffee farmers to invest in industrial activities that turned São Paulo into Brazil's largest industrial hub.

- Crime rates consistently decreased in the 21st century. The citywide homicide rate was 6.56 in 2019, less than half the 27.38 national rate.[72]

- Air quality[73] has steadily increased during the modern era.

- The two major rivers crossing the city, Tietê and Pinheiros, are highly polluted. A major project to clean up these rivers is underway.

- The Clean City Law or antibillboard, approved in 2007, focused on two main targets: anti-publicity and anti-commerce. Advertisers estimate that they removed 15,000 billboards and that more than 1,600 signs and 1,300 towering metal panels were dismantled by authorities.[74]

- São Paulo metropolitan region, adopted vehicle restrictions from 1996 to 1998 to reduce air pollution during wintertime. Since 1997, a similar project was implemented throughout the year in the central area of São Paulo to improve traffic.[75]

Languages

The primary language is Portuguese. The general language from São Paulo General, or Tupi Austral (Southern Tupi), was the Tupi-based trade language of what is now São Vicente, São Paulo, and the upper Tietê River. In the 17th century it was widely spoken in São Paulo and spread to neighboring regions while in Brazil. From 1750 on, following orders from Marquess of Pombal, Portuguese language was introduced through immigration and consequently taught to children in schools. The original Tupi Austral language subsequently lost ground to Portuguese, and eventually became extinct. Due to the large influx of Japanese, German, Spanish, Italian and Arab immigrants etc., the Portuguese idiom spoken in the metropolitan area of São Paulo reflects influences from those languages. Due to globalization, English is now spoken by some residents as a foreign language.

The Italian influence in São Paulo accents is evident in the Italian neighborhoods such as Bela Vista, Moóca, Brás and Lapa. Italian mingled with Portuguese and as an old influence, was assimilated or disappeared into spoken language. The local accent with Italian influences became notorious through the songs of Adoniran Barbosa, a Brazilian samba singer born to Italian parents who used to sing using the local accent.[76]

Other languages spoken in the city are mainly among the Asian community: São Paulo is home to the largest Japanese population outside Japan. Although today most Japanese-Brazilians speak only Portuguese, some of them are still fluent in Japanese. Some people of Chinese and Korean descent are still able to speak their ancestral languages.[77] In some areas it is still possible to find descendants of immigrants who speak German[78] (especially in the area of Brooklin paulista) and Russian or East European languages (especially in the area of Vila Zelina).[79] In the west zone of São Paulo, specially at Vila Anastácio and Lapa region, there is a Hungarian colony, with three churches (Calvinist, Baptist and Catholic), so on Sundays it is possible to see Hungarians talking to each other on sidewalks.

Sexual diversity

.jpg)

The Greater São Paulo is home to a prominent self-identifying gay, bisexual and transgender community, with 9.6% of the male population and 7% of the female population declaring themselves to be non-straight.[80] Same-sex civil unions have been legal in the whole country since 5 May 2011, while same-sex marriage in São Paulo was legalized on 18 December 2012. Since 1997, the city has hosted the annual São Paulo Gay Pride Parade, considered the biggest pride parade in the world by the Guinness Book of World Records with over 5 million participants, and typically rivalling the New York City Pride March for the record.[16]

Strongly supported by the State and the City of São Paulo government authorities, in 2010, the city hall of São Paulo invested R$1 million reais in the parade and provided a solid security plan, with approximately 2,000 policemen, two mobile police stations for immediate reporting of occurrences, 30 equipped ambulances, 55 nurses, 46 medical physicians, three hospital camps with 80 beds. The parade, considered the city's second largest event after the Formula One, begins at the São Paulo Museum of Art, crosses Paulista Avenue, and follows Consolação Street to Praça Roosevelt in Downtown São Paulo. According to the LGBT app Grindr, the gay parade of the city was elected the best in the world.[81]

Government

As the capital of the state of São Paulo, the city is home to the Bandeirantes Palace (state government) and the Legislative Assembly. The Executive Branch of the municipality of São Paulo is represented by the mayor and his cabinet of secretaries, following the model proposed by the Federal Constitution.[82] The organic law of the municipality and the Master Plan of the city, however, determine that the public administration must guarantee to the population effective tools of manifestation of participatory democracy, which causes that the city is divided in regional prefectures, each one led by a Regional Mayor appointed by the Mayor.[83]

The legislative power is represented by the Municipal Chamber, composed of 55 aldermen elected to four-year posts (in compliance with the provisions of Article 29 of the Constitution, which dictates a minimum number of 42 and a maximum of 55 for municipalities with more than five million inhabitants). It is up to the house to draft and vote fundamental laws for the administration and the Executive, especially the municipal budget (known as the Law of Budgetary Guidelines).[84] In addition to the legislative process and the work of the secretariats, there are also a number of municipal councils, each dealing with different topics, composed of representatives of the various sectors of organized civil society. The actual performance and representativeness of such councils, however, are sometimes questioned.

The following municipal councils are active: Municipal Council for Children and Adolescents (CMDCA); of Informatics (WCC); of the Physically Disabled (CMDP); of Education (CME); of Housing (CMH); of Environment (CADES); of Health (CMS); of Tourism (COMTUR); of Human Rights (CMDH); of Culture (CMC); and of Social Assistance (COMAS) and Drugs and Alcohol (COMUDA). The Prefecture also owns (or is the majority partner in their social capital) a series of companies responsible for various aspects of public services and the economy of São Paulo:

- São Paulo Turismo S/A (SPTuris): company responsible for organizing large events and promoting the city's tourism.

- Companhia de Engenharia de Tráfego (CET)[85]: subordinated to the Municipal Transportation Department, is responsible for traffic supervision, fines (in cooperation with DETRAN) and maintenance of the city's road system.

- Companhia Metropolitana de Habitação de São Paulo (COHAB): subordinate to the Department of Housing, is responsible for the implementation of public housing policies, especially the construction of housing developments.

- Empresa Municipal de Urbanização de São Paulo (EMURB): subordinate to the Planning Department, is responsible for urban works and for the maintenance of public spaces and urban furniture.

- Companhia de Processamento de Dados de São Paulo (PRODAM): responsible for the electronic infrastructure and information technology of the city hall.

- São Paulo Transportes Sociedade Anônima (SPTrans): responsible for the operation of the public transport systems managed by the city hall, such as the municipal bus lines.

Subdivisions

São Paulo is divided into 32 sub-prefectures, each with an administration ("subprefeitura") divided into several districts ("distritos").[83] The city also has a radial division into nine zones for purpose of traffic control and bus lines, which don't fit into the administrative divisions. These zones are identified by colors in the street signs. The historical core of São Paulo, which includes the inner city and the area of Paulista Avenue, is in the Subprefecture of Sé. Most other economic and tourist facilities of the city are inside an area officially called Centro Expandido (Portuguese for "Broad Centre", or "Broad Downtown"), which includes Sé and several other subprefectures, and areas immediately located around it.

| Subprefectures of São Paulo[86] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subprefecture | Area | Population | Subprefecture | Area | Population | |||

| 1 | Aricanduva/Vila Formosa | 21.5 km² | 266 838 |  |

17 | Mooca | 35.2 km² | 305 436 |

| 2 | Butantã | 56.1 km² | 345 943 | 18 | Parelheiros | 353.5 km² | 110 909 | |

| 3 | Campo Limpo | 36.7 km² | 508 607 | 19 | Penha | 42.8 km² | 472 247 | |

| 4 | Capela do Socorro | 134.2 km² | 561 071 | 20 | Perus | 57.2 km² | 109 218 | |

| 5 | Casa Verde/Cachoeirinha | 26.7 km² | 313 176 | 21 | Pinheiros | 31.7 km² | 270 798 | |

| 6 | Cidade Ademar | 30.7 km² | 370 759 | 22 | Pirituba/Jaraguá | 54.7 km² | 390 083 | |

| 7 | Cidade Tiradentes | 15 km² | 248 762 | 23 | Sé | 26.2 km² | 373 160 | |

| 8 | Ermelino Matarazzo | 15.1 km² | 204 315 | 24 | Santana/Tucuruvi | 34.7 km² | 327 279 | |

| 9 | Freguesia do Ó/Brasilândia | 31.5 km² | 391 403 | 25 | Jaçanã/Tremembé | 64.1 km² | 255 435 | |

| 10 | Guaianases | 17.8 km² | 283 162 | 26 | Santo Amaro | 37.5 km² | 217 280 | |

| 11 | Ipiranga | 37.5 km² | 427 585 | 27 | São Mateus | 45.8 km² | 422 199 | |

| 12 | Itaim Paulista | 21.7 km² | 358 888 | 28 | São Miguel Paulista | 24.3 km² | 377 540 | |

| 13 | Itaquera | 54.3 km² | 488 327 | 29 | Sapopemba | 13.4 km² | 296 042 | |

| 14 | Jabaquara | 14.1 km² | 214 200 | 30 | Vila Maria/Vila Guilherme | 26.4 km² | 302 899 | |

| 15 | Lapa | 40.1 km² | 270 102 | 31 | Vila Mariana | 26.5 km² | 311 019 | |

| 16 | M'Boi Mirim | 62.1 km² | 523 138 | 32 | Vila Prudente | 33.3 km² | 480 823 | |

Twin towns – sister cities

São Paulo is twinned with:[87]

Economy

.jpg)

São Paulo is considered the "financial capital of Brazil", as it is the location for the headquarters of major corporations and of banks and financial institutions. São Paulo is Brazil's highest GDP city and the 10th largest in the world,[89] using Purchasing power parity.[90]

According to data of IBGE, its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2010 was R$450 billion,[91] approximately US$220 billion, 12.26% of Brazilian GDP and 36% of all production of goods and services of the State of São Paulo.[92]

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers average annual economic growth of the city is 4.2%.[93] São Paulo also has a large "informal" economy.[94] In 2005, the city of São Paulo collected R$90 billion in taxes and the city budget was R$15 billion. The city has 1,500 bank branches and 70 shopping malls.[95]

As of 2014, São Paulo is the third largest exporting municipality in Brazil after Parauapebas, PA and Rio de Janeiro, RJ. In that year São Paulo's exported goods totaled $7.32B (USD) or 3.02% of Brazil's total exports. The top five commodities exported by São Paulo are soybean (21%), raw sugar (19%), coffee (6.5%), sulfate chemical wood pulp (5.6%), and corn (4.4%).[96]

The São Paulo Stock Exchange (BM&F Bovespa) is Brazil's official stock and bond exchange. It is the largest stock exchange in Latin America, trading about R$6 billion (US$3.5 billion) every day.[97]

São Paulo's economy is going through a deep transformation. Once a city with a strong industrial character, São Paulo's economy has followed the global trend of shifting to the tertiary sector of the economy, focusing on services. The city is unique among Brazilian cities for its large number of foreign corporations.[98]

63% of all the international companies with business in Brazil have their head offices in São Paulo. São Paulo has one of the largest concentrations of German businesses worldwide[99] and is the largest Swedish industrial hub alongside Gothenburg.[100]

São Paulo ranked second after New York in FDi magazine's bi-annual ranking of Cities of the Future 2013/14 in the Americas, and was named the Latin American City of the Future 2013/14, overtaking Santiago de Chile, the first city in the previous ranking. Santiago now ranks second, followed by Rio de Janeiro.[101]

The per capita income for the city was R$32,493 in 2008.[102] According to Mercer's 2011 city rankings of cost of living for expatriate employees, São Paulo is now among the ten most expensive cities in the world, ranking 10th in 2011, up from 21st in 2010 and ahead of London, Paris, Milan and New York City.[103][104]

Science and technology

.jpeg)

The city of São Paulo is home to research and development facilities and attracts companies due to the presence of regionally renowned universities. Science, technology and innovation is leveraged by the allocation of funds from the state government, mainly carried out by means of the Foundation to Research Support in the State of São Paulo (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo – FAPESP), one of the main agencies promoting scientific and technological research.[105]

Luxury goods

Luxury brands tend to concentrate their business in São Paulo. Because of the lack of department stores and multi-brand boutiques, shopping malls as well as the Jardins district, which is more or less the Brazilian's Rodeo Drive version, attract most of the world's luxurious brands.

Most of the international luxury brands can be found in the Iguatemi, Cidade Jardim or JK shopping malls or on the streets of Oscar Freire, Lorena or Haddock Lobo in the Jardins district. They are home of brands such as Cartier, Chanel, Dior, Giorgio Armani, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Marc Jacobs, Tiffany & Co.

Cidade Jardim was opened in São Paulo in 2008, it is a 45,000-square-metre (484,376-square-foot) mall, landscaped with trees and greenery scenario, with a focus on Brazilian brands but also home to international luxury brands such as Hermès, Jimmy Choo, Pucci and Carolina Herrera. Opened in 2012, JK shopping mall has brought to Brazil brands that were not present in the country before such as Goyard, Tory Burch, Llc., Prada, and Miu Miu.[106]

The Iguatemi Faria Lima, in Faria Lima Avenue, is Brazil's oldest mall, opened in 1966.[107] The Jardins neighborhood is regarded among the most sophisticated places in town, with upscale restaurants and hotels. The New York Times once compared Oscar Freire Street to Rodeo Drive.[108] In Jardins there are luxury car dealers. One of the world's best restaurants as elected by The World's 50 Best Restaurants Award, D.O.M.,[109] is located there.

Tourism

Large hotel chains whose target audience is the corporate traveler are in the city. São Paulo is home to 75% of the country's leading business fairs. The city also promotes one of the most important fashion weeks in the world, São Paulo Fashion Week, established in 1996 under the name Morumbi Fashion Brasil, is the largest and most important fashion event in Latin America.[110] Besides, the São Paulo Gay Pride Parade, held since 1997 on Paulista Avenue is the event that attracts more tourists to the city.[111]

The annual March For Jesus is a large gathering of Christians from Protestant churches throughout Brazil, with Sao Paulo police reporting participation in the range of 350,000 in 2015.[112] In addition, São Paulo hosts the annual São Paulo Pancake Cook-Off in which chefs from across Brazil and the world participate in competitions based on the cooking of pancakes.[113]

Cultural tourism also has relevance to the city, especially when considering the international events in the metropolis, such as the São Paulo Art Biennial, that attracted almost 1 million people in 2004.

The city has a nightlife that is considered one of the best in the country. There are cinemas, theaters, museums, and cultural centers. The Rua Oscar Freire was named one of the eight most luxurious streets in the world, according to the Mystery Shopping International,[114] and São Paulo the 25th "most expensive city" of the planet.[115]

According to the International Congress & Convention Association, São Paulo ranks first among the cities that host international events in Americas and the 12th in the world, after Vienna, Paris, Barcelona, Singapore, Berlin, Budapest, Amsterdam, Stockholm, Seoul, Lisbon, and Copenhague.[116] According to a study by MasterCard in 130 cities around the world, São Paulo was the third most visited destination in Latin America (behind Mexico City and Buenos Aires) with 2.4 million foreign travelers, who spent US$2.9 billion in 2013 (the highest among the cities in the region). In 2014, CNN ranked nightlife São Paulo as the fourth best in the world, behind New York City, Berlin and Ibiza, in Spain.[117]

The cuisine of the region is a tourist attraction. The city has 62 cuisines across 12,000 restaurants.[118] During the 10th International Congress of Gastronomy, Hospitality and Tourism (Cihat) conducted in 1997, the city received the title of "World Gastronomy Capital" from a commission formed by 43 nations' representatives.[119]

Urban infrastructure

Since the beginning of the 20th century, São Paulo has been one of the main economic center of Latin America. With the First and Second World Wars and the Great Depression, coffee exports to the United States and Europe were heavily affected, forcing the rich coffee growers to invest in the industrial activities that would make São Paulo the largest industrial center in Brazil. The new job vacancies contributed to attract a significant number of immigrants (mainly from Italy)[120] and migrants, especially from the Northeastern states.[121] From a population of only 32.000 people in 1880, São Paulo now has 8.5 million inhabitants in 1980. The rapid population growth has brought many problems for the city.

São Paulo is practically all served by the water supply network. The city consumes an average of 221 liters of water/inhabitant/day while the UN recommends the consumption of 110 liters/day. The water loss is 30.8%. However, between 11 and 12.8% of households do not have a sewage system, depositing waste in pits and ditches. Sixty percent of the sewage collected is treated. According to data from IBGE and Eletropaulo, the electricity grid serves almost 100% of households. The fixed telephony network is still precarious, with coverage of 67.2%. Household garbage collection covers all regions of the municipality but is still insufficient, reaching around 94% of the demand in districts such as Parelheiros and Perus. About 80% of the garbage produced daily by Paulistas is exported to other cities, such as Caieiras and Guarulhos.[122] Recycling accounts for about 1% of the 15,000 tonnes of waste produced daily.[122]

Urban fabrics

São Paulo has a myriad of urban fabrics. The original nuclei of the city are vertical, characterized by the presence of commercial buildings and services; And the peripheries are generally developed with two to four-story buildings – although such generalization certainly meets with exceptions in the fabric of the metropolis. Compared to other global cities (such as the island cities of New York City and Hong Kong), however, São Paulo is considered a "low-rise building" city. Its tallest buildings rarely reach forty stories, and the average residential building is twenty. Nevertheless, it is the fourth city in the world in quantity of buildings, according to the page specialized in research of data on buildings Emporis Buildings,[123] besides possessing what was considered until 2014 the tallest skyscraper of the country, the Mirante do Vale, also known as Palácio Zarzur Kogan, with 170 meters of height and 51 floors.[124]

Such tissue heterogeneity, however, is not as predictable as the generic model can make us imagine. Some central regions of the city began to concentrate indigents, drug trafficking, street vending and prostitution, which encouraged the creation of new socio-economic centralities. The characterization of each region of the city also underwent several changes throughout the 20th century. With the relocation of industries to other cities or states, several areas that once housed factory sheds have become commercial or even residential areas.[125]

The constant change of the landscape of São Paulo due to the technological changes of its buildings has been a striking feature of the city, pointed out by scholars. In a period of a century, between the middle of 1870 and 1970 the city of São Paulo was "practically demolished and rebuilt at least three times". These three periods are characterized by the typical constructive processes of their times.

Urban planning

São Paulo has a history of actions, projects and plans related to urban planning that can be traced to the governments of Antonio da Silva Prado, Baron Duprat, Washington and Luis Francisco Prestes Maia. However, in general, the city was formed during the 20th century, growing from village to metropolis through a series of informal processes and irregular urban sprawl.[126]

Urban growth in São Paulo has followed three patterns since the beginning of the 20th century, according to urban historians: since the late 19th Century and until the 1940s, São Paulo was a condensed city in which different social groups lived in a small urban zone separated by type of housing; from the 1940s to the 1980s, São Paulo followed a model of center-periphery social segregation, in which the upper and middle-classes occupied central and modern areas while the poor moved towards precarious, self-built housing in the periphery; and from the 1980s onward, new transformations have brought the social classes closer together in spatial terms, but separated by walls and security technologies that seek to isolate the richer classes in the name of security.[127]

Thus, São Paulo differs considerably from other Brazilian cities such as Belo Horizonte and Goiânia, whose initial expansion followed determinations by a plan, or a city like Brasília, whose master plan had been fully developed prior to construction.[128]

The effectiveness of these plans has been seen by some planners and historians as questionable. Some of these scholars argue that such plans were produced exclusively for the benefit of the wealthier strata of the population while the working classes would be relegated to the traditional informal processes. In São Paulo until the mid-1950s, the plans were based on the idea of "demolish and rebuild", including former Mayor Prestes Maia São Paulo's road plan (known as the Avenues Plan) or Saturnino de Brito's plan for the Tietê River.

The Plan of the Avenues was implemented during the 1920s and sought to build large avenues connecting the city center with the outskirts. This plan included renewing the commercial city center, leading to real estate speculation and gentrification of several downtown neighborhoods . The plan also led to the expansion of bus services, which would soon replace the trolley as the preliminary transportation system.[129] This contributed to the outwards expansion of São Paulo and the peripherization of poorer residents. Peripheral neighborhoods were usually unregulated and consisted mainly of self-built single-family houses.[127]

In 1968 the Urban Development Plan proposed the Basic Plan for Integrated Development of São Paulo, under the administration of Figueiredo Ferraz. The main result was zoning laws. It lasted until 2004 when the Basic Plan was replaced by the current Master Plan.[130]

That zoning, adopted in 1972, designated "Z1" areas (residential areas designed for elites) and "Z3" (a "mixed zone" lacking clear definitions about their characteristics). Zoning encouraged the growth of suburbs with minimal control and major speculation.[131]

After the 1970s peripheral lot regulation increased and infrastructure in the periphery improved, driving land prices up. The poorest and the newcomers were now unable to purchase their lot and build their house, and were forced to look for a housing alternative. As a result, favelas and precarious tenements (cortiços) appeared.[132] These housing types were often located closer to the center of the city: favelas could sprawl in any terrain that had not previously been utilized (often dangerous or unsanitary) and decaying or abandoned buildings for tenements were abundant inside the city. Favelas went back into the urban perimeter, occupying the small lots that had not yet been occupied by urbanization – alongside polluted rivers, railways, or between bridges.[133]

By 1993, 19.8% of São Paulo's population lived in favelas, compared to 5.2% in 1980.[134] Today, it is estimated that 2.1 million Paulistas live in favelas, which represents about 11% of the total population of the metropolitan area.[135]

Education

São Paulo has public and private primary and secondary schools and vocational-technical schools. More than nine-tenths of the population are literate and roughly the same proportion of those age 7 to 14 are enrolled in school. There are 578 universities in the state of São Paulo.[136]

Educational institutions

The universities and colleges include:

- Universidade de São Paulo (USP) (University of São Paulo)

- Insper Instituto de Ensino e Pesquisa (Insper-SP) (Insper Institute of Education and Research)

- INPG Business School

- Escola Superior de Propaganda e Marketing (ESPM) (Superior School of Advertising and Marketing)

- Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie (MACKENZIE-SP) (Mackenzie Presbyterian University)

- Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP) (Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo)

- Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo (IFSP) (São Paulo Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology)

- Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho (Unesp) (São Paulo State University Júlio de Mesquita Filho)

- Faculdade de Tecnologia de São Paulo (FATEC) (São Paulo Technological College)

- Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP) (Federal University of São Paulo)

- Centro Universitário Belas Artes de São Paulo(University of Fine Arts of São Paulo)

- Universidade de Mogi das Cruzes (UMC) (University of Mogi das Cruzes)

- Universidade Paulista (UNIP) (Paulista University)

- Universidade São Judas Tadeu (USJT) (São Judas Tadeu University/"São Judas University")

- Escola Superior de Propaganda e Marketing (ESPM-SP) (Superior School of Advertising and Marketing)

- Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV-SP) (Getúlio Vargas Foundation)

- Fundação Escola de Comércio Álvares Penteado (FECAP) (School of Commerce Alvares Penteado Foundation)

- Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado (FAAP) (Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation)

- Universidade Anhembi Morumbi (Anhembi Morumbi University)

- Faculdades Metropolitanas Unidas (FMU) (UMC, United Metropolitan Colleges)

- Instituto Brasileiro de Mercado de Capitais (Ibmec-SP) (Brazilian Capital Market Institute)

- Faculdade de Comunicação Social Cásper Líbero (Cásper Líbero Social Communication College)

- Faculdade Santa Marcelina (FASM) (Santa Marcelina College)

- Universidade de Santo Amaro (Unisa) e Faculdade de Medicina de Santo Amaro (OSEC)

- Universidade Nove de Julho (UNINOVE)

- Centro Universitário São Camilo (CUSC) (Saint Camillus University Center)

Health care

São Paulo is one of the largest health care hubs in Latin America. Among its hospitals are the Albert Einstein Israelites Hospital, ranked among the best in Latin America and the Hospital das Clínicas, the largest in the region.

The private health care sector is very large and most of Brazil's best hospitals are located in the city. As of September 2009, the city of São Paulo had:[137]

- 32,553 ambulatory clinics, centers and professional offices (physicians, dentists and others);

- 217 hospitals, with 32,554 beds;

- 137,745 health care professionals, including 28,316 physicians.

Municipal health

The municipal government operates public health facilities across the city's territory, with 770 primary health care units (UBS), ambulatory and emergency clinics and 17 hospitals. The Municipal Secretary of Health has 59,000 employees, including 8,000 physicians and 12,000 nurses.

6,000,000 citizens uses the facilities, which provide drugs at no cost and manage an extensive family health program (PSF – Programa de Saúde da Família).

The Rede São Paulo Saudável (Healthy São Paulo Network) is a satellite-based digital TV corporate channel, developed by the Municipal Health Secretary of São Paulo, bringing programs focused on health promotion and health education, which may be watched by citizens seeking health care in its units in the city.

The network consists of two studios and a system for transmission of closed digital video in high definition via satellite, with about 1,400 points of reception in all health care units of the municipality of São Paulo.

Transport

Highways

Automobiles are the main means to get into the city. In March 2011, more than 7 million vehicles were registered.[138] Heavy traffic is common on the city's main avenues and traffic jams are relatively common on its highways.

The city is crossed by 10 major motorways:

- Rodovia Presidente Dutra/BR-116 (President Dutra Highway) – connects São Paulo to the east and north-east of the country. Most important connection: Rio de Janeiro.

- Rodovia Régis Bittencourt/BR-116 (Régis Bittencourt Highway) – connects São Paulo to the south of the country. Most important connections: Curitiba and Porto Alegre.

- Rodovia Fernão Dias/BR-381 (Fernão Dias Highway) – Connects São Paulo to the north of the country. Most important connection: Belo Horizonte.

- Rodovia Anchieta/SP-150 (Anchieta Highway) – connects São Paulo to the ocean coast. Mainly used for cargo transportation to Santos Port. Most important connection: Santos.

- Rodovia dos Imigrantes/SP-150 (Immigrants Highway) – connects São Paulo to the ocean coast. Mainly used for tourism. Most important connections: Santos, São Vicente, Guarujá and Praia Grande.

- Rodovia Castelo Branco/SP-280 (President Castelo Branco Highway) – connects São Paulo to the west and north-west of the country. Most important connections: Osasco, Sorocaba, Bauru, Jaú, Araçatuba and Campo Grande.

- Rodovia Raposo Tavares/SP-270 (Raposo Tavares Highway) – connects São Paulo to the west of the country. Most important connections: Cotia, Sorocaba, Presidente Prudente.

- Rodovia Anhangüera/SP-330 (Anhanguera Highway) – connects São Paulo to the north-west of the country, including its capital city. Most important connections: Campinas, Ribeirão Preto and Brasília.

- Rodovia dos Bandeirantes/SP-348 (Bandeirantes Highway) – connects São Paulo to the north-west of the country. It is considered the best motorway of Brazil. Most important connections: Campinas, Ribeirão Preto, Piracicaba and São José do Rio Preto.

- Rodovia Ayrton Senna/SP-70 (Ayrton Senna Highway) – named after Brazilian legendary Formula One driver Ayrton Senna, the motorway connects São Paulo to east locations of the state, as well as the north coast of the state. Most important connections: São Paulo–Guarulhos International Airport, São José dos Campos and Caraguatatuba.

Rodoanel

Rodoanel Mário Covas (official designation SP-021) is the beltway of the Greater São Paulo, Brazil. Upon its completion, it will have a length of 177 km (110 mi), with a radius of approximately 23 km (14 mi) from the geographical center of the city. It was named after Mário Covas, who was mayor of the city of São Paulo (1983–1985) and a state governor (1994-1998/1998-2001) until his death from cancer. It is a controlled access highway with a speed limit of 100 km/h (62 mph) under normal weather and traffic circumstances. The west, south and east parts are completed, and the north part, which will close the beltway, is due to 2018.[139] and is being built by DERSA.[140]

Airports

São Paulo has two main airports, São Paulo–Guarulhos International Airport (IATA: GRU) for international flights and national hub, and Congonhas-São Paulo Airport (IATA: CGH) for domestic and regional flights. Another airport, the Campo de Marte Airport, serves private jets and light aircraft. The three airports together moved more than 58.000.000 passengers in 2015, making São Paulo one of the top 15 busiest in the world, by number of air passenger movements. The region of Greater São Paulo is also served by Viracopos-Campinas International Airport, São José dos Campos Airport and Jundiaí Airport.

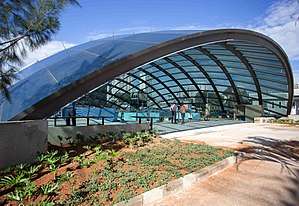

Congonhas Airport operates flights mainly to Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte and Brasília. In the latest upgrade, twelve boarding bridges were installed to provide more comfort to passengers by eliminating the need to walk in the open to their flights. The terminal area was expanded from 37.3 thousand square metres (0.4 million square feet) to over 70 thousand square metres (0.75 million square feet). This expansion raised capacity to almost 18 million users. Built in the 1930s, it was designed to handle the increasing demand for flights, in the fastest growing city in the world. Located in Campo Belo District, Congonhas Airport is close to the three main city's financial districts: Paulista Avenue, Brigadeiro Faria Lima Avenue and Engenheiro Luís Carlos Berrini Avenue.

São Paulo–Guarulhos International, also known as "Cumbica" is 25 km (16 mi) north-east of the city center, in the neighbouring city of Guarulhos. Every day nearly 110.000 people pass through the airport, which connects Brazil to 36 countries around the world. 370 companies operate there, generating more than 53.000 jobs. With capacity to serve 42 million passengers a year, in three terminals, the airport handles 40 million users.

Construction of a third passenger terminal was completed in time to the 2014 World Cup, and raised yearly capacity to 42 million passengers. The project is part of the airport's master plan, which will raise, by the end of 2032, the airport capacity to nearly 60 million passengers. São Paulo International Airport is also the main air cargo hubs in Brazil. The roughly 150 flights a day carry everything from fruits grown in the São Francisco Valley to locally manufactured medicine and electronics devices. The airport's cargo terminal is South America's largest. In 2015, over 503.675 tons were transported from the airport.[142] Both São Paulo–Guarulhos International Airport and Congonhas-São Paulo Airport will be connected to the metropolitan rail system by the end of 2018, with lines Line 13 (CPTM) and Line 17 (São Paulo Metro), respectively.

Campo de Marte is located in Santana district, the northern zone of São Paulo. The airport handles private flights and air shuttles, including air taxi firms. Opened in 1935, Campo de Marte is the base for the largest helicopter fleet in Brazil and the world's, ahead of New York and Tokyo, with a fleet of more than 3.500 helicopters. This airport is the home base of the State Civil Police Air Tactical Unit, the State Military Police Radio Patrol Unit and the São Paulo Flying Club.[143] From this airport, passengers can take advantage of some 350 remote helipads and heliports to bypass heavy road traffic.[144] Campo de Marte also hosts the Ventura Goodyear Blimp.

São Paulo Catarina Executive Airport located in São Roque handles general aviation traffic.

Urban rail transit

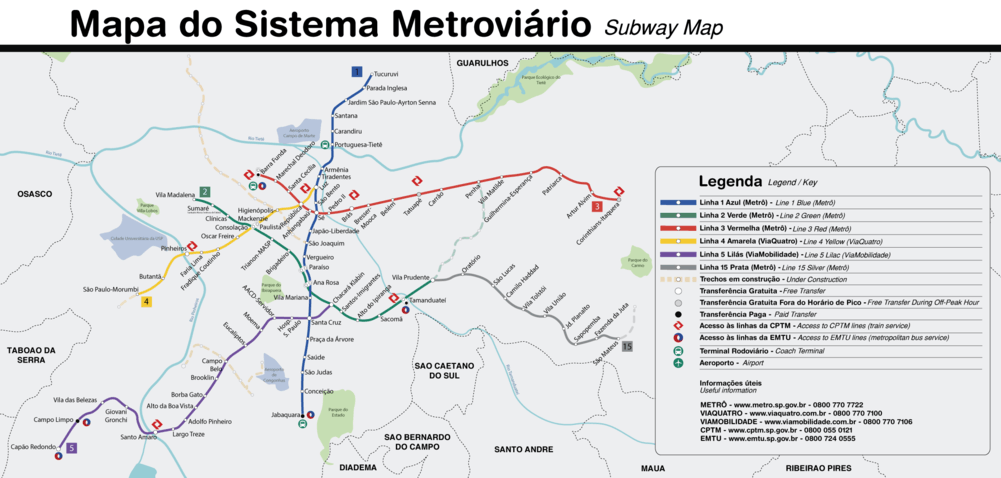

São Paulo has three urban rail transit systems: the São Paulo Metro (locally known as the Metrô), an underground system with six lines, which includes the monorail of the Line 15 (Silver), and the commuter rail system of the Companhia Paulista de Trens Metropolitanos (CPTM), with seven lines that serve cities in the metropolitan region. The underground and railway lines carry some 7 million people on an average weekday together.[145] The systems combined form a 370 km (230 mi) long network of urban rail transit.[146]

The São Paulo Metro operates 101 kilometres (63 mi) of rapid transit system, with six lines in operation, serving 89 stations.[147] In 2015, the metro reached the mark of 11.5 million passengers per mile of line, 15% higher than in 2008, when 10 million users were taken per mile. It is the largest concentration of people in a single transport system in the world, according to the company. The company ViaQuatro, a private concessionaire, operates the Line 4 of the system.[148] In 2014, the São Paulo Metro was elected the best metro system in the Americas.[149]

The Line 15 (Silver) of the São Paulo Metro is the first mass-transit monorail of the South America and the first system in the world to use the Bombardier Innovia Monorail 300. When fully completed will be the largest and highest capacity monorail system in the Americas and second worldwide, only behind to the Chongqing Monorail.[150]

The Companhia Paulista de Trens Metropolitanos (CPTM, or "Paulista Company of Metropolitan Trains") railway add 273.0 km (169.6 mi) of commuter rail, with seven lines and 94 stations. The system carries about 2.8 million passengers a day. On June 8, 2018, CPTM set a weekday ridership record with 3,096,035 trips.[151] The Line 13 (Jade) of the CPTM connects São Paulo to the São Paulo–Guarulhos International Airport, in the municipality of Guarulhos, the first major international airport in South America to be directly served by train.[152]

The two major São Paulo railway stations are Luz and Julio Prestes in the Luz/Campos Eliseos region. Julio Prestes Station connected Southwest São Paulo State and Northern Paraná State to São Paulo City. Agricultural products were transferred to Luz Station from which they headed to the Atlantic Ocean and overseas. Julio Prestes stopped transporting passengers through the Sorocabana or FEPASA lines and now only has metro service. Due to its acoustics and interior beauty, surrounded by Greek revival columns, part of the rebuilt station was transformed into the São Paulo Hall.

Luz Station was built in Britain and assembled in Brazil. It has an underground station and is still active with metro lines that link São Paulo to the Greater São Paulo region to the East and the Campinas Metropolitan region in Jundiaí in the western part of the State. Luz Station is surrounded by important cultural institutions such as the Pinacoteca do Estado, The Museu de Arte Sacra on Tiradentes Avenue and Jardim da Luz, among others. It is the seat of the Santos-Jundiaí line which historically transported international immigrants from the Port of Santos to São Paulo and the coffee plantation lands in the Western region of Campinas. São Paulo has no tram lines, although trams were common in the first half of the 20th century.[153]

A high-speed railway service is proposed to link São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.[154] The trains are projected to reach 280 kilometres per hour (170 mph), taking about 90 minutes. Another important project is the "Expresso Bandeirantes", a medium-speed rail service (about 160 km/h or 99 mph) from São Paulo to Campinas, which would reduce the journey time from 90 minutes by car to about 50 minutes, linking São Paulo, Jundiaí, Campinas Airport and Campinas city center. This service is also to connect to the railway service between São Paulo city center and Guarulhos Airport. Work on an express railway service between São Paulo city center and Guarulhos International Airport were announced by the São Paulo state government in 2007.[155]

Buses