Chapultepec Castle

Chapultepec Castle (Spanish: Castillo de Chapultepec) is located on top of Chapultepec Hill in Mexico City's Chapultepec park. The name Chapultepec is the Nahuatl word chapoltepēc which means "at the grasshopper's hill". The castle has such unparalleled views and terraces that historian James F. Elton wrote that they can't "be surpassed in beauty in any part of the world".[1][2] It is located at the entrance to Chapultepec Park at a height of 1,203 meters above sea level. The site of the hill was a sacred place for Aztecs, and the buildings atop it have served several purposes during its history, including that of Military Academy, Imperial residence, Presidential residence, observatory, and since the 1940s, the National Museum of History.[3] Chapultepec, along with Iturbide Palace, are the only royal palaces in North America.

| Chapultepec Castle | |

|---|---|

Castillo de Chapultepec | |

View of Chapultepec Castle from the Northeast | |

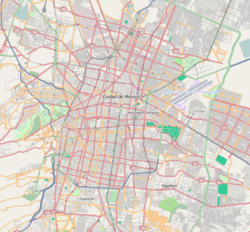

Location in Mexico City | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Neo-romanticism, Neoclassical, Neo-Gothic |

| Location | Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico City, Mexico |

| Coordinates | 19°25′14″N 99°10′54″W |

| Elevation | 2,325 metres (7,628 ft) above sea level |

| Current tenants | Museo Nacional de Historia |

| Construction started | c. 1785 |

| Completed | 1864 |

| Height | 220 feet (67 m) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Eleuterio Méndez, Ramón Cruz Arango ity, Julius Hofmann, Carl Gangolf Kayser, Carlos Schaffer |

| Other designers | Maximilian I of Mexico |

It was built during the Viceroyalty as summer house for the highest colonial administrator, the viceroy. It was given various uses, from the gunpowder warehouse to the military academy in 1841. It became the official residence of Emperor Maximilian I and his consort Empress Carlota during the Second Mexican Empire (1864–67). In 1882, President Manuel González declared it the official residence of the President. With few exceptions, all succeeding presidents lived there until 1939, when President Lázaro Cárdenas turned it into a museum.

Colonial period

In 1785 Viceroy Bernardo de Gálvez ordered the construction of a stately home for himself at the highest point of Chapultepec Hill. Francisco Bambitelli, Lieutenant Colonel of the Spanish Army and engineer, drew up the blueprint and began the construction on August 16 of the same year. After Bambitelli's departure to Havana, Captain Manuel Agustín Mascaró took over the leadership of the project and during his tenure the works proceeded at a rapid pace. Mascaró was accused of building a fortress with the intent of rebelling against the Spanish Crown from there. Bernardo, the viceroy, died suddenly on November 8, 1786, fueling speculation that he was poisoned. No evidence has yet been found which supports this claim.

Lacking a head engineer, the Spanish Crown ordered that the building be auctioned at a price equivalent to one-fifth of the quantity thus far spent on its construction. After finding no buyers Viceroy Juan Vicente de Güemes Pacheco de Padilla y Horcasitas intended the building to house the General Archive of the Kingdom of the New Spain; that idea was not to come to fruition either despite already having the blueprints adapted for this purpose. German scientist Alexander von Humboldt visited the site in 1803 and condemned the Royal Treasury's sale of the palace’s windows to raise funds for the Crown. The building was finally bought in 1806 by the municipal government of Mexico City.

Independence

Chapultepec Castle was abandoned during the Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821) and for many years later, until 1833. In that year the building was decreed to become the location of the Military College (Military Academy) for cadet training; as a sequence of several structural modifications had to be done, including the addition of the watchtower known as Caballero Alto ("Tall Knight").

On September 13, 1847, the Niños Héroes ("Boy Heroes") died defending the castle while it was taken by United States forces during the Battle of Chapultepec of the Mexican–American War. They are honored with a large mural on the ceiling above the main entrance to the castle.[4]

The United States Marine Corps honors its role in the Battle of Chapultepec and the subsequent occupation of Mexico City through the first line of the "Marines' Hymn," From the Halls of Montezuma.[5] Marine Corps tradition maintains that the red stripe worn on the trousers of officers and noncommissioned officers, and commonly known as the blood stripe commemorates the high number of Marine NCOs and officers killed storming the castle of Chapultepec in September 1847. As noted, the usage "Halls of Montezuma" is factually wrong - as the building was erected by the Spanish rulers of Mexico, more than two centuries after the Aztec Emperor Montezuma was overthrown.

Several new rooms were built on the second floor of the palace during the tenure of President Miguel Miramón, who was also an alumnus of the Military Academy.

Second Mexican Empire

When Mexican conservatives invited Maximilian von Hapsburg to establish the Second Mexican Empire, the castle, now known as Castillo de Miravalle, became the residence of the emperor and his consort in 1864. The Emperor hired several European and Mexican architects to renovate the building for the royal couple, among them Julius Hofmann, Carl Gangolf Kayser, Carlos Schaffer, Eleuterio Méndez and Ramón Cruz Arango,[6] The architects designed several projects, which followed a neoclassical style and made the palace more habitable as a royal residence. European architects Kayser and Hofmann worked on several other revival castles, including Neuschwanstein Castle[7] – built by Maximilian's Wittelsbach cousin Ludwig II of Bavaria twenty years after Chapultepec's renovation.

Botanist Wilhelm Knechtel was in charge of creating the roof garden on the building. Additionally, the Emperor brought from Europe countless pieces of furniture, objets d'art and other fine household items that are exhibited to this day.

At this time, the castle was on the outskirts of Mexico City. Maximilian ordered the construction of a straight boulevard (modeled after the great boulevards of Europe, such as Vienna's Ringstrasse and the Champs-Élysées in Paris), to connect the Imperial residence with the city center, and named it Paseo de la Emperatriz ("Promenade of the Empress"). Following the reestablishment of the Republic in 1867 by President Benito Juárez and the end of the civil war to oust the French invaders and defeat their Mexican conservative allies, the boulevard was renamed Paseo de la Reforma, after the Liberal reform.

Modern era to present

The castle fell into disuse after the fall of the Second Mexican Empire in 1867. In 1876, a decree established it as an Astronomical, Meteorological and Magnetic Observatory on the site, which was opened in 1878 during the presidency of Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada. However, the observatory was only functional for five years until they decided to move it to the former residence of the Archbishop in Tacubaya. The reason was to allow the return of the Colegio Militar to the premises as well as transforming the building into the presidential residence.

The palace underwent several structural changes from 1882 and during the presidency of Porfirio Díaz (1876-1880; 1884-1911). When Díaz was overthrown at the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution it remained the presidential residence. Presidents Francisco I. Madero (1911-13), Venustiano Carranza (1915-20), Álvaro Obregón (1920-24), Plutarco Elías Calles (1924-28), Emilio Portes Gil, Pascual Ortiz Rubio and Abelardo Rodríguez. It was used for a time as an official guest house or residence for foreign dignitaries.

Finally on February 3, 1939, President Lázaro Cárdenas decreed a law establishing Chapultepec Castle as the National Museum of History, with the collections of the former National Museum of Archaeology, History and Ethnography, (now the National Museum of Cultures). The museum was opened on September 27, 1944 during the presidency of Manuel Avila Camacho. President Cárdenas moved the official Mexican presidential residence to Los Pinos, and never lived in Chapultepec Castle.

In popular culture

- In 1996, the castle was a film location for the Academy Award-nominated movie William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes. Many views of the castle as the Capulet Mansion can be seen throughout the film.[8]

- In the 1954 American war film Vera Cruz starring Gary Cooper and Burt Lancaster, Chapultepec was portrayed using elaborate sets and decor.

- In the 2006 video game Ghost Recon: Advanced Warfighter, a level existed in and around the castle.

- Chapultepec Castle has been used as a model of castle architecture to design buildings such as the 13th Regiment Armory (Sumner Armory), in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, US.[9]

Gallery

- Main entrance, just beyond the gate

- Side entrance into the museum

Monument to the Niños Héroes. Chapultepec Castle can be seen in the background

Monument to the Niños Héroes. Chapultepec Castle can be seen in the background View from the slopes of the hill of Chapultepec in the woods of the same name

View from the slopes of the hill of Chapultepec in the woods of the same name Dining room

Dining room The Malachite Room

The Malachite Room The bedroom of Maximilian of Mexico

The bedroom of Maximilian of Mexico Stained glass windows along a hallway

Stained glass windows along a hallway Castle grounds

Castle grounds Statues of the Niños Héroes

Statues of the Niños Héroes- Tower in the garden of the Alcázar

References

- Elton, James Frederick (26 July 1867). "With the French in Mexico". hdl:2027/gri.ark:/13960/t79s61v86. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - O’Connor, William (28 May 2018). "Chapultepec, the Mexican Castle That Drove a Belgian Princess to Madness and an Austrian Archduke to the Firing Squad". Thedailybeast.com. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Historia de Chapultepec". Museo Nacional de Historia. Archived from the original on 2009-11-14. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- "Mural of Cadet Jumping - Mexico501". Mexico501.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-08. Retrieved 2014-10-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-11-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hendel, archINFORM – Sascha. "Julius Hofmann". Eng.archinform.net.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-06-18. Retrieved 2009-11-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-06-05. Retrieved 2009-11-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chapultepec Castle. |