Parque México

The Parque México (English: lit. "Mexico Park"), officially Parque San Martín,[2] is a large urban park located in Colonia Hipódromo in the Condesa area of Mexico City. It is recognized by its Art Deco architecture and decor as well as being one of the larger green areas in the city.[1] In 1927, when the surrounding neighborhood of Colonia Hipódromo was being built, the park was developed on the former site of the horse race track of the Jockey Club de México. Today, Parque México is not only the center of Colonia Hipódromo, it is also the cultural center of the entire La Condesa section of the city.

| Parque México | |

|---|---|

| Parque San Martín | |

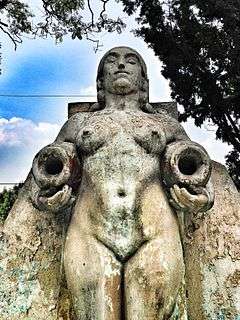

Fuente de los Cántaros (Fountain of the jugs) by José María Fernández Urbina, for which Luz Jiménez modeled | |

Parque México location in central/western Mexico City | |

| Location | Avenida México, Colonia Hipódromo, Condesa, Mexico City |

| Coordinates | 19°24′44″N 99°10′09″W |

| Area | 88,000 square metres (22 acres) |

| Opened | December 13, 1927[1] |

| Designer | Architect: Leonardo Noriega; Engineer: Javier Stávoli |

| Operated by | Cuauhtémoc borough |

| Public transit access | Metrobús Sonora stop |

| features | Lindbergh Forum; fountains incl. Fuente de los Cántaros; art deco clock and fountain, north fountain; duck pond; covered benches (novelty architecture); original instructional signs in engraved concrete |

Description

The park is located on Avenida México and Calle de Michoacán in Colonia Hipódromo, only two blocks from Avenida Insurgentes, one of the city’s main arteries.[3] It was the first modern park, created with an architectural design. It copies many of the elements of European gardens, such as ponds and walkways.[4] It has an extension of nine hectares in an elliptical design.[4] The park differs from other major parks such as the Alameda Central or Parque España. More traditional parks in Mexico City have paths that cut diagonally through them, but Parque Mexico's paths are more “organic” and less rigid, wandering around the various attractions.[4] The park hosts various cultural events, neighborhood gatherings and considered to be fashionable place to meet people.[1] One can see children playing soccer and riding bikes while adults stroll or exercise or just relax on the benches.[3]

The park contains a number of other fountains, ponds, waterfalls and light posts that simulate tree trunks.[4] A large pond or small lake is inhabited by ducks and swans.[1] Many of the trees and other plants are native to humid areas of the Mediterranean such as Lebanese cypress, mimosas, and palms. There is also more exotic flora such as bamboo. Some of the existing trees were planted when the park was established.[4] The clock tower is Art Deco with ironwork and bells to mark the hour.[1] In the past, the clock tower played classical music to mark the hour.[4]

The best known feature is the Teatro al Aire Libre Lindbergh (Lindbergh Open Air Theater), or simply Foro Lindbergh (Lindbergh Forum) which consists of five monumental pillars, topped with marquesinas and surrounded by a serpentine pergola. There is also a fountain (Fuente de los Cántaros) with a sculpture of a woman with large jars, from which water used to flow. This was created by José María Hernández Urbina; the model was Luz Jiménez, who also modeled for Diego Rivera. The five pillars define the stage area, which also contains a four-section relief/mural by Roberto Montenegro, called “Alegoría al Teatro.[1][4] The forum is in an extreme disrepair, though in January 2013 the borough announced that it had secured budget to repair it.[5]

The park and its surroundings

The park is the center of Colonia Hipódromo, which was built around it.[4] Most of the colonia’s streets follow the lines of or lead to the park, and the houses that surround the park match the park’s Art Deco style.[4] Around the park are a number of important architectural examples from the 1920s and 1930s such as the Edificio San Martín and the Edificio México.[1] The building is important because it retains classic architectural features prevalent in the 1930s, such as the bedrooms having the best views, rather than the living room. This building was restored between 1998 and 2001 by architect Carlos Duclaud, when it was almost completely in ruins.[6]

The park not only serves as the center of Colonia Hipodromo, it is also the defining element of the larger Condesa area of the city.[1][3] The park is also considered to be “lungs” of the Condesa.[7]

The park has been recognized by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), as part of the heritage of the city.[4]

History

The park was created at the same time as Colonia Hipódromo in the 1920s. The entire Condesa area, along with Colonia Roma, was part of a hacienda of the Countess (condesa) of Miravalle. The Countess held horse races on her property, where Parque Mexico is now. The hacienda was sold and developed bit by bit until all that remained was the race track, which could not be developed into residential units because of environmental laws.[3]

When the nearest section to the track of the old hacienda was being developed, it was decided to turn the racetrack into a park, with the colonia centered on and built around it. This was the idea of José Luis Cuevas. This made some of the main streets of Colonia Hipódromo curved, around the park/track with others leading to the park. This is unique in Mexico City and distinguishes Hipodromo from the other colonias of La Condesa, Colonia Condesa and Colonia Hipódromo Condesa.[1][4]

It was the first modern park, created with an architectural design. It copies many of the elements of European gardens, such as ponds and walkways.[4] The park was designed by architect Leonardo Noriega and engineer Javier Stávoli, who took advantage of the unusually large size of the park to divide it into sections for different activities.[1]

Renovation

Since it was established in the 1920s, the park has degraded over time. In 2008, renovation work was carried out on the park and other green areas in the La Condesa zone. In Parque Mexico, renovation included a treatment plant, an irrigation system, rejuvenating the garden areas, better lighting and restoration work on the Lindbergh Theater. However, not all residents were happy with the renovation work, especially in relation to the green areas. Some blame the city for not consulting with them about changes first and not sharing information about the renovation work. One point of conflict is whether or not to allow people to walk on the grass.[7]

There are also tensions among users of the park over the presence of household dogs. One of the problems concerns the lack of control some owners have over their animals, but the more serious problem is the feces left behind. The problem has spurred rumors passed along via Facebook and Twitter that some are leaving poisoned meatballs in the park.[8]

In 2010, the city government installed WiFi service in the park, free for use. It is among the 600 public spaces in which the city has installed free “hotspots.”[9]

In October 2013 a 600,000-peso (US$31,696) renovation started, which included an overall paint job and was to include restoration of the Lindbergh Forum.[10]

References

- "Parque México" (in Spanish). Mexico: Ciudad Mexico.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- The Rough Guide to Mexico. London: Penguin. 2016. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-241-27955-7.

- "Urbanismo: Parque México: Pulmón de la colonia Condesa" (in Spanish). Mexico: Noticias Architectura. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- "Analizan el Parque México" (in Spanish). Mexico: INAH. January 27, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- "Delegación Cuauhtémoc: la tercera, ¿será la vencida?: Se destina un presupuesto para rescatar el Foro Lindbergh del Parque México en la colonia Condesa, anuncia el jefe delegacional", Excelsior, 17 January 2013

- "Edificio San Martín" (in Spanish). Mexico: Obras Web. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- Rocío González Alvarado (March 27, 2008). "El parque México, otro punto de conflicto entre los residentes de la colonia Condesa" [Parque Mexico, another point of conflicto among residents of Colonia Condesa]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- Phenélope Aldaz (August 16, 2010). "Dueños de perros y visitantes a parque México buscan convivir" [Dog owners and visitors to Parque Mexico seek to get along]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- Redacción/SDP (August 26, 2010). "Arranca internet gratuito en Parque México" [Free internet available in Parque Mexico]. SDP Noticias (in Spanish). Mexico. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- "Arrancan la rehabilitación del Parque México", Más por más (newspaper), October 20, 2013

External links