Museo Nacional de Arte

The Museo Nacional de Arte (MUNAL) (English: National Museum of Art) is the Mexican national art museum, located in the historical center of Mexico City. The museum is housed in a neoclassical building at No. 8 Tacuba, Col. Centro, Mexico City. It includes a large collection representing the history of Mexican art from the mid-sixteenth century to the mid 20th century. It is recognizable by Manuel Tolsá's large equestrian statue of Charles IV of Spain, who was the monarch just before Mexico gained its independence. It was originally in the Zocalo but it was moved to several locations, not out of deference to the king but rather to conserve a piece of art, according to the plaque at the base.[1] It arrived at its present location in 1979.

Museo Nacional de Arte | |

| |

| Location | Historical center of Mexico City |

|---|---|

| Website | www |

The institution

The museum was founded in 1982 as the Museo Nacional de Arte, and re-inaugurated in 2000, after reopening its doors to the public as MUNAL after intense remodeling and technical upgrades to the facility. It currently focuses on the exhibition, study and diffusion of Mexican and international art from the 16th century to the first half of the 20th century. Its permanent collection contains more than 3,000 pieces and has 5,500m2 of exhibition space. MUNAL is a subdivision of the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes and as part of this organization is involved in projects concerning the conservation, exhibition, and study of the fine arts of Mexico. The museum also offers workshops, colloquiums, publication and other outreaches to the public. There are also volunteer opportunities such as the Voluntariado and the Amigos de MUNAL associations.[2]

The Palace of Communications building

MUNAL is located in the old Palace of Communications. In the early part of the 20th century, the government hired Italian architect Silvio Contri to design and build this “palace” to house the Secretariat of Communications and Public Works, with the intention to show Mexico's commitment to modernization. The Palace was constructed on the former site of the hospitals of San Andres and of Gonzalez Echeverria. The architectural design is eclectic, mixing elements of past architectural styles, which is characteristic of that time period. This blending would later solidify into a movement called “modernismo” both because of the tendency to use newly devised construction techniques and the tendency to use metal in the decorative aspects, to symbolize progress in the Industrial Age. The decorative elements of the building were done by the Coppedé family of Florence, who designed the door knockers, the window frames, the leaded crystal, the stonework, the furniture, lamps and ironwork among many other elements. Over the years, much of the Palace deteriorated until around 2000, when Project MUNAL restored the palace to its original look, while also adding the latest technology for the preservation of artistic works.[3]

Two rooms that stand out are the decoration of the Reception Hall and the sculptures in the Patio de los Leones.[3] The Reception Hall is on the second floor and designed to imitate the splendor of similar halls in Europe. It is profusely decorated with precious metal and crystal ornaments as well as allegorical murals dedicated to themes such as science, the arts, liberty, history, work and progress. The work devoted to the concept of progress subdivides into four themes of force, justice, wisdom and wealth. This hall became the preferred place for President Porfirio Díaz to perform public declarations and receive dignitaries from abroad.[4] Like the rest of the building the Patio of the Liones synthesizes a number of different architectural styles. The two primary styles seen here are Classic and Gothic with other styles introduced in the forms of sculptures, lighting and sculpted stonework. In the center is a large semicircular staircase to the upper floors.[5]

Later in the 20th century, the building served as the Archivo General de la Nación and from 1982 as the Museo Nacional de Arte. The plaza in front of the building is named after Manuel Tolsá, who created the statue of Carlos IV there, also known as El Caballito.[3] Today almost all of the building is used to house the permanent collection of MUNAL with the Reception Hall and the Patio de los Leones used for events such as concerts, book-signings and press conferences.[4][5]

The collection

The museum’s permanent collection is designed to give a panoramic view of the development of the fine arts in Mexico from the early colonial period to the mid-twentieth century. The artwork is subdivided into three distinct periods. The first covers the colonial period from 1550 to 1821. The second covers the first century after Independence and the third covers the period after the Mexican Revolution to the 1950s.[6] Works created after that time period are on display at a number of museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in Chapultepec Park.[7]

The collection of art from the colonial period is entitled “Asimilación de occidente” (Assimilation of the West) and are contained within Salons 1-14 on the second floor. This collection shows how western-style painting transferred over and synthesized in Mexico, eventually leading to the establishment of Mexico’s own fine arts institution, the Academy of San Carlos, the first of its kind in the Americas. Art from the first century of Mexican Independence (1810–1910) is entitled “La construcción de la Nación” (Construction of a Nation) housed in Salons 19-26 of the second floor. Coinciding with the Romanticism period, most paintings have themes such as Mexican customs and landscapes with the purpose of defining a Mexican identity. The last time period is titled “Estrategías plásticas para un México moderno” (Strategies for the fine arts in modern Mexico) and house in Salons 27-33 on the first floor. Historically, this period is after the end of the Mexican Revolution when questions of modernity and nationalism were foremost. It also coincides with the development of the Mexican muralist movement.[6][8]

Some of the salons are devoted to temporary exhibitions, such as the paintings of Pedro Gualdi from the 19th century,[9] and more contemporary photography exhibitions by Carlos Monsivais and Marina Yampolsky.[10] One of the latest exhibitions was called “The Practice of Everyday Life” which occurred in 2009.[11]

Gallery

- View of central staircase from bottom.

San Carlos Borromeo Repartiendo Limosna al Pueblo by Jose Salome Pina.

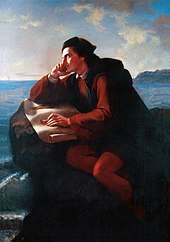

San Carlos Borromeo Repartiendo Limosna al Pueblo by Jose Salome Pina. Inspiracion de Cristobal Colon by Jose Maria Obregon.

Inspiracion de Cristobal Colon by Jose Maria Obregon.- Cristobal Colon en la corte de los Reyes Catolicos by Juan Cordero.

The Viceroy Duque de Linares by Juan Rodriguez Juarez.

The Viceroy Duque de Linares by Juan Rodriguez Juarez. Interior del Colegio de Infantes de la Catedral de México, José Jiménez, 1857.

Interior del Colegio de Infantes de la Catedral de México, José Jiménez, 1857.- Moctezuma en Chapultepec by Daniel del Valle.

Self portrait of José María Velasco Gómez

Self portrait of José María Velasco Gómez

Painting of the India Oaxaqueña by Ramón Cano Manilla.

Painting of the India Oaxaqueña by Ramón Cano Manilla.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Museo Nacional de Arte (Mexico). |

References

- Noble, John (2000). Lonely Planet Mexico City. Oakland California: Lonely Planet. p. 115. ISBN 1-86450-087-5.

- "MUNAL" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2009-07-08. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- "Historia del Antiguo Palacio de Comunicaciones" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- "Salon de Recepciones" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2013-02-21. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- "El Patio de Leones" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2013-02-21. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- "El recorrido Historico Artistico" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2013-02-21. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- Gomez, Edgard M (February 2007). "Mexico City's Moment". Art and Antiques. 30 (2): 104–105. ISSN 0195-8208.

- "El Las colecciones" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- Tibol, Raquel (June 1997). "Pietro Gualdi. (Museo Nacional de Arte,México, D.F., México)". Proceso (in Spanish).

- "Ciclo de Primavera en el Munal: Heroes y Valentones. (Living in Mexico).(photography exhibition, Museu Nacional de Arte, Mexico City)(Brief Article)". Business Mexico (in Spanish). 2001.

- Monsalve, Federico (May 2009). "The Practice of Everyday Life". ARTnews. 108 (5): 125–125. ISSN 0004-3273.