Baja California

Baja California[note 1] (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈbaxa kaliˈfoɾnja] (![]()

Baja California | |

|---|---|

State | |

| Free and Sovereign State of Baja California | |

| Anthem: "Canto a Baja California" | |

State of Baja California within Mexico | |

| Coordinates: 30°00′N 115°10′W | |

| Country | Mexico |

| Before statehood | North Territory of BC |

| Admission | 16 January 1952[1] (29th) |

| Capital | Mexicali |

| Largest city | Tijuana |

| Largest metro | Tijuana |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Jaime Bonilla (MRN) |

| • Legislature | Baja California Congress |

| • Senators | Gerardo Novelo (MRN) Alejandra León (MRN) Gina Cruz (PAN) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 71,450 km2 (27,590 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 12th |

| Population (2015)[3] | |

| • Total | 3,315,766 |

| • Rank | 14th |

| • Density | 46/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 19th |

| Demonym(s) | Bajacaliforniano(a) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT[a]) |

| Postal code | 21, 22 |

| Area code | |

| ISO 3166 code | MX-BCN |

| HDI | |

| GDP | US$29 billion[b] |

| Website | Official Web Site |

| ^ a. 2010 and later. Baja California is the only state to use the US DST schedule state wide, while the rest of Mexico (except for small portions of other northern states) starts DST 3–4 weeks later and ends DST one week earlier.[4] ^ b. The state's GDP was 294.8 billion of pesos in 2008,[5] amount corresponding to 23.03 billion of dollars, being a dollar worth 12.80 pesos (value of 3 June 2010).[6] | |

The state has an estimated population of 3,315,766 (2015),[7] significantly higher than the sparsely populated Baja California Sur to the south, and similar to San Diego County, California on its north. Over 75% of the population lives in the capital city, Mexicali, in Ensenada, or in Tijuana. Other important cities include San Felipe, Rosarito and Tecate. The population of the state is composed of Mestizos, mostly immigrants from other parts of Mexico, and, as with most northern Mexican states, a large population of Mexicans of Spanish ancestry, and also a large minority group of East Asian, Middle Eastern and indigenous descent. Additionally, there is a large immigrant population from the United States due to its proximity to San Diego and the lower cost of living compared to San Diego. There is also a significant population from Central America. Many immigrants moved to Baja California for a better quality of life and the number of higher paying jobs in comparison to the rest of Mexico and Latin America.

Baja California is the twelfth largest state by area in Mexico. Its geography ranges from beaches to forests and deserts. The backbone of the state is the Sierra de Baja California, where the Picacho del Diablo, the highest point of the peninsula, is located. This mountain range effectively divides the weather patterns in the state. In the northwest, the weather is semi-dry and mediterranean. In the narrow center, the weather changes to be more humid due to altitude. It is in this area where a few valleys can be found, such as the Valle de Guadalupe, the major wine-producing area in Mexico. To the east of the mountain range, the Sonoran Desert dominates the landscape. In the south, the weather becomes drier and gives way to the Vizcaino Desert. The state is also home to numerous islands off both of its shores. In fact, the westernmost point in Mexico, the Guadalupe Island, is part of Baja California. The Coronado, Todos Santos and Cedros Islands are also on the Pacific Shore. On the Gulf of California, the biggest island is the Angel de la Guarda, separated from the peninsula by the deep and narrow Canal de Ballenas.

History

Prehistory and Spanish colonial era

The first people came to the peninsula at least 11,000 years ago. At that time two main native groups are thought to have been present on the peninsula. In the south were the Cochimí. In the north were several groups belonging to the Yuman language family, including the Kiliwa, Paipai, Kumeyaay, Cocopa, and Quechan. These peoples were diverse in their adaptations to the region. The Cochimí of the peninsula's Central Desert were generalized hunter-gatherers who moved frequently; however, the Cochimí on Cedros Island off the west coast had developed a strongly maritime economy. The Kiliwa, Paipai, and Kumeyaay in the better-watered northwest were also hunter-gatherers, but that region supported denser populations and a more sedentary lifestyle. The Cocopa and Quechan of northeastern Baja California practiced agriculture in the floodplain of the lower Colorado River.

Another group of people were the Guachimis, who came from the north and created much of the Sierra de Guadalupe cave paintings. Not much is known about them except that they lived in the area between 100 BC and the coming of the Europeans and created World Heritage rock art.[8]

Europeans reached the present state of Baja California in 1539, when Francisco de Ulloa reconnoitered its east coast on the Gulf of California and explored the peninsula's west coast at least as far north as Cedros Island. Hernando de Alarcón returned to the east coast and ascended the lower Colorado River in 1540, and Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo (or João Rodrigues Cabrilho (in Portuguese)) completed the reconnaissance of the west coast in 1542. Sebastián Vizcaíno again surveyed the west coast in 1602, but outside visitors during the following century were few.

The Jesuits founded a permanent mission colony on the peninsula at Loreto in 1697. During the following decades, they gradually extended their sway throughout the present state of Baja California Sur. In 1751–1753, the Croatian Jesuit mission-explorer Ferdinand Konščak made overland explorations northward into the state of Baja California. Jesuit missions were subsequently established among the Cochimí at Santa Gertrudis (1752), San Borja (1762), and Santa María (1767).

After the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1768, the short-lived Franciscan administration (1768–1773) resulted in one new mission at San Fernando Velicatá. More importantly, the 1769 expedition to settle Alta California under Gaspar de Portolà and Junípero Serra resulted in the first overland exploration of the northwestern portion of the state.[9]

The Dominicans took over management of the Baja California missions from the Franciscans in 1773. They established a chain of new missions among the northern Cochimí and western Yumans, first on the coast and subsequently inland, extending from El Rosario (1774) to Descanso (1817), just south of Tijuana.

In 1804, the Spanish crown divided California into Alta ("Upper") and Baja ("Lower") California at the line separating the Franciscan missions in the north from the Dominican missions in the south. The colonial governors were 1804–1805 José Joaquín de Arillaga (1804-5), Felipe de Goicoechea, 1806-14, and José Darío Argüello, 1814-April 11, 1822.

Post-independence, 1821-present

Early republic

Mexican liberals were concerned that the Roman Catholic Church retained too much power in the post-independence period and sought to undermine it by mandating the secularization of missions in 1833. In the aftermath of the Mexican American War 1846-48 and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the United States gained sovereignty over territory previously held first by New Spain and then Mexico, most of which was sparsely settled. Alta California was incorporated into the U.S. and after the 1849 gold strikes quickly gained enough population to be admitted to the union as a state. Baja California remained under Mexican control. In 1853, soldier of fortune William Walker captured La Paz, declaring himself President of the Republic of Baja California. The Mexican government forced his retreat after several months.

Era of Porfirio Díaz

When liberal army general Porfirio Díaz came to power in 1876, he embarked on a major program to develop and modernize Mexico.

- 1884: Luis Huller and George H. Sisson obtain a concession covering much of the present state, in return for promises to develop the area.[10]

- 1905: The Magonista revolution, an anarchist movement based on the writings of Ricardo Flores Magón and Enrique Flores Magón, begins.

- 1911: Mexicali and Tijuana are captured by the Mexican Liberal Party (Partido Liberal Mexicano, PLM), but soon surrender to Federal forces.

Postrevolutionary Mexico

- 1917: On 11 December, "[a] prominent Mexican, close friend of President Carranza" offered to U. S. Senator Henry Ashurst to sell Baja California to the U. S. for "fifty million dollars gold."[11]

- 1930: Baja California is further divided into Northern and Southern territories.

- 1952: The North Territory of Baja California becomes the 29th state of Mexico, Baja California. The southern portion, below 28°N, remains a federally administered territory.

- 1974: The South Territory of Baja California becomes the 31st state, Baja California Sur.

- 1989: Ernesto Ruffo Appel of the PAN becomes the first non-PRI governor of Baja California and the first opposition governor of any state since the Revolution.

Geography

Baja California encompasses a territory, within The Californias region of North America, which exhibits diverse geography for a relatively small area. The Peninsular ranges of the California cordillera run down the geographic center of the state. The most notable ranges of these mountains are the Sierra de Juarez and the Sierra de San Pedro Martir. These ranges are the location of forests reminiscent of Southern California's San Gabriel Mountains. Picacho del Diablo is the highest peak in the whole peninsula. Valleys between the mountain ranges are located within a climate zone that are suitable for agriculture. Such valleys included the Valle de Guadalupe and the Valle de Ojos Negros, areas that produce citrus fruits and grapes. The mineral-rich mountain range extends southwards to the Gulf of California, where the western slope becomes wider, forming the Llanos del Berrendo in the border with Baja California Sur. The mountain ranges located in the center and southern part of the state include the Sierra de La Asamblea, Sierra de Calamajué, Sierra de San Luis and the Sierra de San Borja.

Temperate winds from the Pacific Ocean and the cold California Current make the climate along the northwestern coast pleasant year-round.[12] As a result of the state's location on the California current, rains from the north barely reach the peninsula, thus leaving southern areas drier. South of El Rosario River the state changes from a Mediterranean landscape to a desert one. This desert exhibits diversity in succulent flora species that flourish in part due to the coastal fog.

To the east, the Sonoran Desert enters the state from both California and Sonora. Some of the highest temperatures in Mexico are recorded in or nearby the Mexicali Valley.[note 2] However, with irrigation from the Colorado River, this area has become truly an agricultural center. The Cerro Prieto geothermal province is near Mexicali as well (this area is geologically part of a large pull apart basin); producing about 80% of the electricity consumed in the state and enough more to export to California. Laguna Salada, a saline lake below sea level lying between the rugged Sierra de Juarez and the Sierra de los Cucapah, is also in the vicinity of Mexicali. The state government has recently been considering plans to revive Laguna Salada.[note 3] The highest mountain in the Sierra de los Cucapah is the Cerro del Centinela or Mount Signal. The Cucapah are the primary indigenous people of that area and up into the Yuma, Arizona area.

There are numerous islands on the Pacific shore. Guadalupe Island is located in the extreme west of the state's boundaries and is the site of large colonies of sea lions. Cedros Island exists in the southwest of the state's maritime region. The Todos Santos Islands and Coronado Islands are located off the coast of Ensenada and Tijuana respectively. All of the islands in the Gulf of California, on the Baja California side, belong to the municipality of Mexicali.

Baja California obtains much of its water from the Colorado River. Historically the river drained into the Colorado River Delta which flowed into the Gulf of California, but due to large demands for water in the American Southwest, less water now reaches the Gulf. The Tijuana metropolitan area also relies on the Tijuana River as a source of water. Much of rural Baja California depends predominantly on wells, a few dams and even oases. Tijuana also purchases water from San Diego County's Otay Water District. Potable water is the largest natural resource issue of the state.

Climate

Baja California's climate varies from Mediterranean to arid. The Mediterranean climate is observed in the northwestern corner of the state where the summers are dry and mild and the winters cool and rainy. This climate is observed in areas from Tijuana to San Quintin and nearby interior valleys. The cold oceanic California Current often creates a low-level marine fog near the coast. The fog occurs along any part of the Pacific Coast of the state.

The change of altitude towards the Sierra de Baja California creates an alpine climate in this region. Summers are cool while winters can be cold with below freezing temperatures at night. It is common to see snow in the Sierra de Juarez and Sierra de San Pedro Martir (and in the valleys in between) from December to April. Due to orographic effects, precipitation is much higher in the mountains of northern Baja California than on the western coastal plain or eastern desert plain. Pine, cedar and fir forests are found in the mountains.

The east side of the mountains produce a rain shadow, creating an extremely arid environment. The Sonoran Desert region of Baja California experiences hot summers and nearly frostless mild winters. The Mexicali Valley (which is below sea level), experiences the highest temperatures in Mexico, that frequently surpass 47 °C (116.6 °F) in mid-summer, and have exceeded 50 °C (122 °F) on some occasions.

Further south along the Pacific coast, the Mediterranean climate transitions into a desert climate but it is milder and not as hot as along the gulf coast. Transition climates, from Mediterranean to Desert, can be found from San Quintin to El Rosario. Further inland and along the Gulf of California the vegetation is scarce and temperatures are very high during the summer months. The islands in the Gulf of California also belong to the desert climate. Some oases can be found in the desert in which few towns are located – for instance, Catavina, San Borja and Santa Gertrudis.[13]

Adjacent States

- California, United States (North)

- Arizona, United States (Northeast)

- Baja California Sur (South)

- Sonora (East)

Flora and fauna

Common trees are the Jeffrey Pine, Sugar Pine and Pinon Pine.[14] Understory species include Manzanita. Fauna include a variety of reptiles including the Western fence lizard, which is at the southern extent of its range.[15] The name of the fish genus Bajacalifornia is derived from the Baja California Peninsula.[16]

In the main terrestrial wildlife refuges on the peninsula of Baja California, Constitution 1857 National Park and Sierra de San Pedro Mártir National Park contain several coniferous species; the most abundant are: Pinus jeffreyi, Pinus ponderosa, Pinus cembroides, Pinus quadrifolia, Pinus monophylla, Juniperus, Arctostaphylos pringlei subsp. drupacea, Artemisia ludoviciana and Adenostoma sparsifolium. The flora share many species with the Laguna Mountains and San Jacinto Mountains in southwest California. The lower elevations of the Sierra Juárez are characterized by chaparral and desert shrub.

The fauna in the parks exhibit a large number of mammals primarily: mule deer, bighorn sheep, cougar, bobcat, ringtail cat, coyote, rabbit, squirrel and more than 30 species of bats. The park is also home to many avian species like: bald eagle, golden eagle, falcon, woodpecker, black vulture, crow, several species of Sittidae and duck.

2010 earthquakes

At 3:40:41 pm PDT on Easter Sunday, 4 April 2010 a 7.2 magnitude northwest trending strike-slip earthquake hit the Mexicali Valley, with its epicenter 26 km southwest of the city of Guadalupe Victoria, Baja California, Mexico.[17] The main shock was felt as far as the Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Phoenix and Tucson metropolitan areas, and in Yuma. At least a half-dozen aftershocks with magnitudes between 5.0 and 5.4 were reported, including a 5.1-magnitude shaker at 4:14 am. that was centered near El Centro.[18] As of 6:31 am PDT, 5 April 2010, two people were confirmed dead.[19]

Government and politics

| Year | PRI | PAN | PRD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 36.99% 446,192 | 27.2% 328,116 | 31.15% 375,803 |

| 2006 | 21.38% 203,233 | 47.35% 450,186 | 23.59% 224,275 |

| 2000 | 37.04% 319,477 | 49.76% 429,194 | 8.97% 77,340 |

| 1994 | 48.92% 402,332 | 36.18% 297,565 | 8.35% 68,669 |

Government

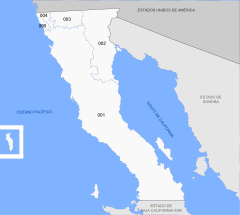

Municipalities of Baja California

Baja California is subdivided into six municipios (municipalities). These are Ensenada, Mexicali, Tecate, Tijuana, Rosarito and San Quintín.

Politics

For a list of the state's historical governors, see: Governor of Baja California.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1895 | 42,875 | — |

| 1900 | 7,583 | −82.3% |

| 1910 | 9,760 | +28.7% |

| 1921 | 23,537 | +141.2% |

| 1930 | 48,327 | +105.3% |

| 1940 | 78,907 | +63.3% |

| 1950 | 226,965 | +187.6% |

| 1960 | 520,165 | +129.2% |

| 1970 | 870,421 | +67.3% |

| 1980 | 1,177,886 | +35.3% |

| 1990 | 1,660,855 | +41.0% |

| 1995 | 2,112,140 | +27.2% |

| 2000 | 2,487,367 | +17.8% |

| 2005 | 2,844,469 | +14.4% |

| 2010 | 3,155,070 | +10.9% |

| 2015 | 3,315,766[21] | +5.1% |

The majority of the population of Baja California is Mestizo, however the state has one of the larger percentages of White (European) Mexicans (about 40%). There are small indigenous communities as well.

Historically, the state has had sizable East Asian immigration. Mexicali has a large Chinese community, as well as many Filipinos who arrived to the state during the eras of Spanish and American rule (1898–1946) in much of the 19th and 20th centuries. Tijuana and Ensenada were a major port of entry for East Asians entering the U.S. ever since the first Asian-Americans were present in California.

Also a significant number of Middle Eastern immigrants such as Lebanese, Syrians and Armenians settle near the U.S. border, and small waves of settlers in the early 20th century, usually members of the Molokan sect of the Russian Orthodox church fled the Russian Revolution of 1917 when the Soviet Union took power, had established a few villages along the Pacific coast south of Ensenada.

Since 1960, large numbers of migrants from southern Mexican states have arrived to work in agriculture (especially the Mexicali Valley and nearby Imperial Valley, California, US) and manufacturing. The cities of Ensenada, Tijuana and Mexicali grew as a result of migrants, primarily those who sought US citizenship and those temporary residents awaiting their entry into the United States are called Flotillas, which is derived from the Spanish word "flota," meaning "fleet."

There is also a sizable immigrant community from Central and South America, and from the United States and Canada. An estimated 200,000+ American expatriates live in the state, especially in coastal resort towns such as Ensenada, known for affordable homes purchased by retirees who continue to hold US citizenship. San Felipe, Rosarito and Tijuana also have a large American population (second largest in Mexico next to Mexico City), particularly for its cheaper housing and proximity to San Diego.

Some 60,000 Oaxacans live in Baja California, the vast majority being indigenous. Some 40% of them lack proper birth certificates.[23]

According to a Conacyt investigator, a bit under a million people were classified as "poor" in the state, up from 2008 when there were roughly 810,000. Exactly who these people are, whether locals, interstate or international migrants, was not explained.[24]

Education

Baja California offers one of the best educational programs in the country, with high rankings in schooling and achievement.

The State Government provides education and qualification courses to increase the workforce standards, such as School-Enterprise linkage programs which helps the development of labor force according to the needs of the industry.

91.60% of the population from six to fourteen years of age attend elementary school. 61.95% of the population over fifteen years of age attend or have already graduated from high school. Public School is available in all levels, from kindergarten to university.

The state has 32 universities offering 103 professional degrees. These universities have 19 research and development centers for basic and applied investigation in advanced projects of biotechnology, physics, oceanography, computer science, digital geothermal technology, astronomy, aerospace, electrical engineering and clean energy, among others. At this educational level, supply is steadily growing. Baja California has developed a need to be self-sufficient in matters of technological and scientific innovation and to be less dependent on foreign countries. Current businesses demand new production processes as well as technology for the incubation of companies. The number of graduate degrees offered, including Ph.D. programs, is 121. The state has 53 graduate schools.[25]

Economy

As of 2005, Baja California's economy represents 3.3% of Mexico's gross domestic product or US$21,996 million.[27] Baja California's economy has a strong focus on tariff-free export oriented manufacturing (maquiladora). As of 2005, 284,255 people are employed in the manufacturing sector.[27] There are more than 900 companies operating under the federal Prosec program in Baja California.

Real estate

The Foreign Investment Law of 1973[28][29] allows foreigners to purchase land within the borders and coasts of Mexico by way of a trust, handled through a Mexican bank (Fideicomiso). This trust assures to the buyer all the rights and privileges of ownership, and it can be sold, inherited, leased, or transferred at any time. Since 1994, the Foreign Investment Law stipulates that the Fideicomiso must be to a 50-year term, with the option to petition for a 50-year renewal at any time.[30]

Any Mexican citizen buying a bank trust property has the option to either remain within the Trust or opt out of it and request the title in "Escritura".

Mexico's early history involved foreign invasions and the loss of vast amounts of land; in fear of history being repeated, the Mexican constitution established the concept of the "Restricted Zone".[31] In 1973, in order to bring in more foreign tourist investment, the Bank Trust of Fideicomiso was created, thus allowing non-Mexicans to own land without any constitutional amendment necessary.[32] Since the law went into effect, it has undergone many modifications in order to make purchasing land in Mexico a safer investment.

Highways

Media

Newspapers of Baja California include:[33] El Centinela, El informador de Baja California, El Mexicano (edición Tijuana), El Mexicano Segunda Edición, El Sol de Tijuana, El Vigía, Esto de las Californias, Frontera, La Crónica de Baja California, La Voz de la Frontera, and Semanario Zeta.[34][35]

See also

Notes

- Sometimes informally referred to as Baja California Norte ("North Lower California") to distinguish it from both the Baja California Peninsula, of which it forms the northern half, and Baja California Sur, the adjacent state that covers the southern half of the peninsula. While it is a well-established term for the northern half of the Baja California Peninsula, it has never existed as a political designation for a state or region.

- Delta in the northeast, recorded 54.0 °C (129.2 °F) on 3 August 1998.

- The state is currently (2008) looking at a plan by SDSU Adj. Professor Newcomb (ICATS) to do this using his geothermal desalination system to supply water locally. SEMARNAT believes this to be the first viable plan presented.

References

- "Transformación Política de Territorio Norte de la Baja California a Estado 29" [The Transformation of Baja California] (in Spanish).

- "Medio Físico del Estado de Baja California". e-local.gob.mx. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- "Encuesta Intercensal 2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Daylight Saving Time Around the World 2010". timeanddate.com.

- "Sistema de Cuantas Nacionales de Mexico" (PDF). 2010. p. 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "Reporte: Jueves 3 de Junio del 2010. Cierre del peso mexicano". www.pesomexicano.com.mx. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- "Principales resultados de la encuesta intercensal 2015" (PDF). COPLADEBC. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- UNESCO World Heritage list number 724 https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/714 retrieved 12 June 2015

- "Mocavo and Findmypast are coming together - findmypast.com". www.mocavo.com.

- de Novelo, Maria Eugenia Bonifaz (1984). "Ensenada: Its background, founding and early development". The Journal of San Diego History. 30 (Winter). Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- Henry Fountain Ashurst, A Many-Colored Toga: The Diary of Henry Fountain Ashurst. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1962. p. 74.

- "Wayback Machine". 25 June 2007. Archived from the original on 25 June 2007.

- Martínez-Ballesté, Andrea; Ezcurra, Exequiel (2018). "Reconstruction of past climatic events using oxygen isotopes in Washingtonia robusta growing in three anthropic oases in Baja California". Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana. 70, 1: 79–94. doi:10.18268/BSGM2018v70n1a5.

- Katharine Layne Brandegee (1894) Zoe: Volume IV, Zoe Publishing Company, Townshend Stith Brandegee

- C. Michael Hogan (2008) "Western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis) Archived 13 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine", Globaltwitcher, ed. Nicklas Stromberg

- C. H. Townsend & J. T. Nichols: Deep sea fishes of the 'Albatross' Lower California Expedition. Bulletin of the AMNH ; v. 52, article 1

- "Magnitude 7.2 – BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- KTVU (4 April 2010). "At Least Two Die In 7.3-Magnitude Baja Quake". KTVU. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- CNN Wire Staff (5 April 2010). "Baja governor seeks emergency declaration after quake". CNN. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- "Presidential elections results". Archived from the original on 21 March 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "Encuesta Intercensal 2015" (PDF). INEGI. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010". INEGI. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- (in Spanish) Con problemas en acta de nacimiento 40% de oaxaqueños en Baja California | Noticiasnet. Noticiasnet.mx (28 November 2012). Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- "Organización Editorial Mexicana". www.oem.com.mx.

- State Government of Baja California and Secretariat of Public Education.

- Muttalib, Bashirah (22 May 2007). "Twentieth Century Fox sells Baja". Variety.

The studio ultimately became one of the industry’s premier water-tank facilities.

- Industrial Costs in Mexico – A Guide for Foreign Investors 2007. Mexico City: Bancomext. 2007. p. 86.

- "Foreign Investment Law" (PDF). gob.mx. Government of Mexico. 9 March 1973. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- Vargas, J. (1994). "Mexico: Foreign Investment Act of 1993". International Legal Materials. 33 (1): 207–224. doi:10.1017/S0020782900027157. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- Mexico and Direct Foreign Ownership of Coastal Property, MexiData.info, 12 April 2010 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Mexico Law Restricted Zone. Mexicolaw.com. Retrieved on 24 May 2014.

- Fideicomiso – Bank Trust – Mexican Real Estate – Mexico Constitution – Mario Restrepo. Bajaopenhouse.com. Retrieved on 24 May 2014.

- Manuel Ortiz Marín, ed. (2006). Los medios de comunicación en Baja California (in Spanish). Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. ISBN 978-970-701-735-1.

- "Publicaciones periódicas en Baja California". Sistema de Información Cultural (in Spanish). Gobierno de Mexico. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- "Latin American & Mexican Online News". Research Guides. US: University of Texas at San Antonio Libraries. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020.

Further reading

- Blaisdell, Lowell L. The Desert Revolution: Baja California 1911. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 1962.

- Castillo-Muñoz, Verónica. The Other California: Land, Identity, and Politics on the Mexican Borderlands Oakland, California: University of California Press 2017. ISBN 9780520291638

- Christiansen, Catherine. "Mujeres Públicas: American Prostitutes in Baja California, 1910-1930," American Historical Review 82 2-1944."(May 2013), 215-47.

- Duncan, Robert H. "The Chinese and the Economic Development of Northern Baja California, 1889-1929." Hispanic American Historical Review 74 no. 4 (1994): 615-47.

- Dwyer, John J. The Agrarian Dispute: The Expropriation of American-Owned Rural Land in Postrevolutionary Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press 2008. ISBN 978-08223-4309-7

- Hart, John Mason. Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico since the Civil War. Berkeley: University of California Press 2002.

- Kerig, Dorothy Pierson. "Yankee Enclave: The Colorado River Land Company and Mexican Agrarian Reform in Baja California 1902-1944." PhD dissertation. University of California, Irvine 1989.

- León-Portilla, Miguel and David Piñera Ramírez, Historia Breve de Baja California. Mexico City: El Colegio de México 2010.

- Martínez, Pablo. Historia de Baja California. Mexico City: Editorial Baja California 1960.

- Owen, Roger c. "Indians and Revolution: The 1911 Invasion of Baja California, Mexico." Ethnohistory 10 no 4 (1963), 373-95.

- Schantz, Eric M. "Behind the Noir Border: Tourism, the Vice Racket, and Power Relations in Baja California's Border Zone, 1938-65" in Holiday in Mexico: Critical Reflections on Tourism and Tourist Encounters, Berger, Dina and Andrew Grant Wood, ed. Durham: Duke University Press 2010

- Stern, Norton B. Baja California: Jewish Refuge and Homeland. Los Angeles: Dawson's Bookshop 1973.

- Vanderwood, Paul. Juan Soldado: Rapist, Martyr, Saint. Durham: Duke University Press 2004.

External links

- Baja California Sur: Cabo Pulmo Coral Reef in Danger

- Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense

- State government (in Spanish)

- Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish)