Tlalpan

Tlalpan (Classical Nahuatl: Tlālpan, lit. 'place on the earth', Nahuatl pronunciation: [ˈtɬaːɬpan̥] (![]()

This center, despite being in the urbanized zone, still retains much of its provincial atmosphere with colonial era mansions and cobblestone streets. Much of the borough's importance stems from its forested conservation areas, as it functions to provide oxygen to the Valley of Mexico and serves for aquifer recharge. Seventy percent of Mexico City's water comes from wells in this borough.

However, the area is under pressure as its mountainous isolated location has attracted illegal loggers, drug traffickers, and kidnappers; the most serious problem is illegal building of homes and communities on conservation land, mostly by very poor people. As of 2010, the government recognizes the existence of 191 of the settlements, which cause severe ecological damage with the disappearance of trees, advance of urban sprawl, and in some areas, the digging of septic pits. The borough is home to one of the oldest Mesoamerican sites in the valley, Cuicuilco, as well as several major parks and ecological reserves. It is also home to a number of semi-independent “pueblos” that have limited self-rule rights under a legal provision known as “usos y costumbres” (lit. uses and customs).

Tlalpan center

What is now called “Tlalpan center” or sometimes “the historic center of Tlalpan” began as a pre-Hispanic village located at the intersection of a number of roads that connected Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) with points south. This village was renamed Villa de San Agustín de las Cuevas in 1645, with the last part “de las Cuevas” referring to the many small caves in the area. During the colonial period, the village was a modest farming village, known for its fruit orchards. However, the forests of the area made it attractive to the elite of Mexico City who built country homes and haciendas here, much as they did in other areas south of the city such as Chimalistac, San Ángel and Coyoacán .[1][2][3]

Many of these homes and manor houses of the former haciendas still remain in and round Tlalpan center.[1][2] As the urban sprawl of Mexico City only began to reach this area starting in the mid-twentieth century, much of the former village has retained its provincial streets, older homes and other buildings with façades of reds, whites, blues and other colors, although a number have been converted into other uses such as cafes, restaurants and museums.[2][3] This makes the area similar to neighboring Coyoacán, and like this neighbor, Tlalpan center is popular with visitors, especially on weekends as people come to see its provincial main square/garden, mansions, narrow winding cobblestone streets lined with large trees, eat in its restaurants and cafes and visit its many nearby parks and other green areas. One popular area with cafes and restaurants is La Portada, on one side of the main plaza.[3][4][5]

Tlalpan center has eighty structures from the 16th to the 20th centuries that have been classified by INAH as having historic value. Some of these include old Tlalpan Hacienda, the former home of the Marquis de Vivanco and the San Agustin parish church.[4] The borough of Tlalpan has sought World Heritage Site status for the area because of these structures, the area's history and the nearby site of Cuicuilco.[6]

The center of this former village is the main square or garden officially called the “Plaza de la Constitución” but better known as the “Jardín Principal” (Main Garden). Visually, what stands out is the large kiosk in the center, but historically more important is the “Arbol de los colgaldos” (Tree of the Hanged). This tree, still alive, was used to hang political enemies and bandits, including those opposed to the invading French Army during the French Intervention in Mexico. On weekends, vendors set up stalls selling handcrafts and other items. To one side of the plaza, there is a cantina called La Jalisciense, one of the oldest in Mexico City, having been in operation for over 135 years.[7]

Facing the Jardín Principal, there is the “Palacio de Gobierno” (Government Palace), which was the site of the government of the State of Mexico, when Tlalpan served as state capital for six years in the early 19th century. Since then, it was used as a barracks for Benito Juárez’s soldiers, a jail, a residence for the Empress Carlota and the site of the Instituto Literario (today the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México) .[1] Today, it serves as the headquarters of the borough, although it is also commonly referred to as the “ex palacio municipal” (former municipal palace) referring to the time when Tlalpan was an independent municipality in the State of Mexico. The current structure was built between 1989 and 1900 in Neoclassical style.[1]

On another side of the main square, there is the San Agustin Church. The village church was established here in 1547 by the Dominicans, but the current structure on the site dates from the 18th century. It has an austere façade and faces the main square. Around it is an atrium, some simple gardens and a patios shaded by fruit trees. A fire at the end of the 19th century destroyed the Baroque altar, replaced with the sober one seen today.[1][2] This parish is the site of the annual San Agustin de las Cuevas Festival, which is the largest religious event in the borough.[6]

Casa Frissac is located just off the main square. It was built in the 19th century in French style as the residence of Jesús Pliego Frissac. According to local legend, bandit Chucho el Roto lived here at one time. In the 20th century, it belonged to Adolfo López Mateos then it became the site of the Lancaster School, which closed in the 1980s. In the 1950s, it was used as a set for the film Los Olvidados, by Luis Buñuel. Today, the house is still the protagonist for a number of local ghost stories; however, its official function is that of a cultural center called the Instituto Javier Barros Sierra. This center began operations in 2001 after 21,800,000 pesos worth of remodeling, which restored the structure to much of its 19th-century look. The center has hosted art exhibits by photographers, graffiti artists, and more—many with a political message. While the center's authorities insist the center is non-political, members of Mexico's PAN party raised objections to the content in the center's first year.[1][8]

The Museo de Historia de Tlalpan (Museum of the History of Tlalpan, is housed in a building known as “La Casona” (The Mansion), which dates to 1874. In addition to its age, one of its claims to fame is that it is the site of the first long distance telephone call in Mexico, calling a telephone in the then-separate Mexico City. This call was made on 20 March 1878 and the telephone used to make the call is on display here.[7][9] The mansion was classified as a historic monument by 1986, and it was converted into the current museum in 2003 after extensive remodeling, which included restoration of the original murals. The museum explores the culture and history of the Tlalpan borough.[9][10] It also has a permanent collection of art work by Gilberto Aceves Navarro, Alberto Castro Leñero, Isabel Leñero, Javier Anzure Joëlle Rapp and Jorge Hernandez.[7][9]

The museum was opened to be part of a “cultural circuit” integrated with other facilities such as Casa Frissac. Prior to the opening of this museum, the only other museum (as opposed to a cultural center focused on classes) was the Museo Soumaya, which is private. Much of the museum's collection of historic items was donated by over one hundred individual residents and include documents, photographs, artworks and more. These donations cover the eight rural “pueblos” in the Ajusco area, traditional barrios and the major apartment complexes in Coapa and San Lorenzo Huipulco as well as Tlalpan center. An organization called the Centro de Documentacion Historica de la Delegacion now accepts, organizes and cares for the borough collection of historic items.[10]

Twenty blocks of Tlalpan center have been designated at the “Museo Público de Arte Contémporaneo de Tlalpan (MUPACT), an “open-air” museum of art, which opened in 2006 with eighteen works. The works are displayed on walls, trees, sidewalks and even streets. The borough offers a nominal fee for works selected to be displayed and requires that said works have a “strong social content.” One of the works that has been displayed was when artist Georgina Toussaint convinced the inmates of a Centro de Tratamiento de Varones to draw images of their identity and then displayed the works on the façade of the facility.[11]

A major attraction of the center, not far from the square, is a manor house that belonged to the former Tlalpan Hacienda. The manor was constructed in 1737 around a central courtyard. Although the hacienda no longer exists, the structure is still surrounded by large gardens. The manor house is currently used as a luxury hotel and restaurant, although there are various salons available as well for events. When it was converted to its present use, it was remodeled in “Neo-Mexican” look with touches of Art Nouveau. The main restaurant offers traditional Mexican dishes with chiles en nogada, cabrito (roast goat), escamoles and duck as specialties. It has large gardens filled with peacocks. Much of the interior décor has been modeled in styles from the 19th century and earlier to evoke the grandeur of the area's upper class of that time.[3][7]

Scattered among the cobblestone streets of the old village are a number of other notable houses and structure from various centuries. The Casa Chata is on the corner of Hidalgo and Matamoros Streets. It was built in the 18th century, with one corner cut off, creating a small façade around the main entrance. The name refers to this feature as “chata” mean flattened, or pushed in.[1][2] As Tlalpan was the capital of the State of Mexico for six years, a number of constructions related to this function, such as the Casa de Moneda (coin mint) and a government print shop were built and still remain. In the latter, Cuban writer José María Heredia published poems about his stay in Mexico.[2]

Other religious institutions include the Convent of the Capuchinas (the Capuchin Poor Clares), which still functions as a convent, where one can buy cookies made by the resident nuns. There is also the Capilla del Calvario, which was built in the 17th century.[1] The former house of the Count De Regla is found on Congreso Street, and on San Fernando Street, there is a house where José María Morelos y Pavón was held prisoner. Another house on this street was occupied by Antonio López de Santa Anna. A notable market in the area is the Mercado de la Paz, which was built in 1900.[1]

This historic center was designated as a "Barrio Mágico" by the city in 2011.[12]

The borough

Political divisions

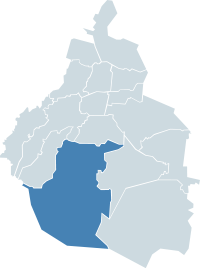

Tlalpan is the largest of Mexico City's sixteen boroughs, and vastly larger than the traditional village of Tlalpan.[2] It has a surface of 310 km² and accounts for 20.6% of Mexico City,[13][14] and a total population of 650,567 inhabitants.[15] It lies at the far south of Mexico City bordering the boroughs of Coyoacán, Xochimilco and Milpa Alta with the state of Morelos to the south and the State of Mexico to the southwest.[16]

Administratively, the borough is divided into five zones: Centro de Tlalpan ( pop. 163,209), Villa Coapa(118,291), Padierna Miguel Hidalgo(148,582) Ajusco Medio (59,905) and Pueblos Rurales(99,447). All of these are divided into neighborhoods variously called “colonias,” “barrios,” “fraccionamientos” or “unidades habitacionales” with the exception of the Pueblo Rurales area, which also contains eight semi independent villages.[17] The far northern zones such as Tlalpan Center, Villa Coapa, and Padierna Miguel Hidalgo are urbanized areas where the sprawl of the city has reach, which the southern sections are still rural. The urbanized areas account for only about 15% of the borough, with the rest belonging to conservation areas or ejido communal lands.[14][18] Pueblos Rurales is the largest zone, but 83% of the borough population is concentrated in the other four.[2][19]

Urban areas

The urban sprawl of Mexico City reached the borough of Tlalpan in the mid-20th century, but only the far north of the borough is urbanized. This area accounts for over 80% of the borough population, who live in a mix of middle class residential areas and large apartment complexes for the lower classes.[17] This northern area is crossed by a number of major road arteries such as the Anillo Periférico, Calzada de Tlalpan, Viaducto-Tlalpan, Acoxpa, Division del Norte/Miramontes, which experience extremely heavy traffic during rush hour.[18] The highway connecting Mexico City with Cuernavaca also passes through the borough. Intersections of these major roads have large commercial and retail complexes such as that of Avenida Insurgentes and Anillo Periferico, which has several of these complexes, as this is a major highway connection for the south of the city.[20]

Traffic and parking are the most serious issues for the areas in the urban areas, as the borough struggles to keep up with the demand but also keep areas such as Tlalpan Centro at least somewhat provincial.[21] Parking problems are greatest in Ajusco Medio, Padiernoa, Pedregales and Colonia Miguel Hidalgo.[18] Traffic problems are worst in Tlalpan center where the narrow streets get jammed by the vehicles of both residents and visitors, especially around the main plaza. The increasing popularity of this area with visitors makes the situation worse on weekends.[4] In the urban areas, problems are similar to that in other parts of Mexico City and include carjacking, illegal firearms, muggings, graffiti, deterioration of infrastructure.[4][22] Most crime is reported in the Villa Coapa with Tlalpan center coming in second.[4]

Rural communities

The rest of the borough is filled with forested areas, rugged mountains and small communities, some of which have had a way of life little changed since colonial times. The Pueblos Rurales Zone contains only about one sixth of the borough's population, with the most important concentrations of people being the eight semi-independent communities.[17] These villages are San Miguel Topilejo, San Pedro Mártir, San Andrés Totoltepec, San Miguel Xicalco, San Miguel Ajusco, Santo Tomás Ajusco, Magdalena Petlacalco, and Parres El Guarda.[23]

These “pueblos” govern much of their local affairs through “usos y costumbres,” modern legal recognition of the old village governing structures still in place, many of which use some form of direct democracy. This is in stark contrast to areas such as Villa Coapa, where almost all local decisions are made by representatives.[17] Because of the rugged terrain, few roads and little police protection, these settlements are isolated.[13] While protected from some of crime problems that affect their urban counterparts, this isolation has made the area attractive for drug runners bringing their merchandise into Mexico City, for kidnappers, illegal logging and more, which has led to a number of murders in the area.[13][24]

Many of high peaks between the borough and the State of Mexico are used as lookouts for criminal organizations. Because of this, the borough ranks ninth in criminal activity.[13] The largest problem is illegal settlements. An estimated 191 forested and other areas have been taken over by about 8,000 families. Some of these communities are over twenty years old.[24] Although some of the illegal construction represents individuals trying to claim a large tract, most of it is shantytowns for the poor with few or no services.[16][22]

Geography and ecology

Tlalpan is located between the mountains that separate Mexico City from the states of Morelos and Mexico and the rocky areas of San Angel, Ciudad Universitaria and the delegation of Coyoacán. The south of the borough consists of the mountain ranges of Chichinautzin and Ajusco, which preserve most of the forested areas remaining in Mexico City. Fifteen of mountains in this area reach at least 3,000 masl, which include the two highest: Cruz del Marqués (3,930masl) and Pico del Aguila (3,880masl) .[2] The borough, like the rest of the Valley of Mexico, lies on central part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt .[25]

Much of the geology of the area formed when the Xitle volcano erupted in 100 CE, which created numerous caves and formed the basis of the volcanic soil that, 600 years later, makes the area's agriculture so productive.[4] The borough has two types of soil: rocky in higher elevations and—in lower areas—less solid and containing more groundwater, making it somewhat spongy.[26] The area experiences regular seismic activity, mostly of low intensity, which is believed mostly from small ancient faults reactivated by regional stresses, or by the sinking of the Valley of Mexico. The south of the Valley, including Tlalpan, is also affected by the underground movement of magma, especially when such contacts the waterlogged regions of the former Lake Xochimilco. Most of these tremors go unnoticed except for those that occur close to the surface such as the one centered 5 km south of the Ciudad Universitaria on 16 October 2005 (mag. 3.1). However, even this one was not felt far from its epicenter.[25] Three areas in the borough are susceptible to seismic activity over 7.5 on the Richter scale: Colonia Isidro Fabela, Villa Coapa, and Tlalpan Centro. These areas are subject to special building inspections and annual earthquake drills.[26] The borough has a warmer and more humid climate than the rest of Mexico City.[2]

As of 2010, 83.5% of the borough was officially defined as conservation space; however, the increase in illegal settlements and logging has been eroding this percentage.[24] The forests are important to the Valley of Mexico/Mexico City as they not only release oxygen into the air, they are an important area for the recharge of the valley's aquifers. Wells from this borough provide 70% of Mexico City's potable water. The borough has 120 wells for potable water (out of a total of 450 in the city), which extract about 60 liters each second from each well. However, water shortages are relatively common in the borough proper. Most of this is due to the lack of wells, drilling equipment and pipelines to serve local residents, with the city authorities only reserving less than a fifth of its infrastructure budget for works in Tlalpan.[20] One serious outage of water occurred in 2001 when thirty nine of the borough's colonias were without dependable water for two weeks because of the lack of water reserves.[27] Deforestation and other ecological damage make a number of areas susceptible to flooding during the rainy season from June to October. These include Anillo Periférico, Renato Leduc, Boulevard de la Luz and the Picacho Highway.[28] Forest fires are a common problem not only in the Bosque de Tlalpan but also in Parque Fuentes Brotantes, Parque Ciudad de Mexico and the Cerro de Zacatepetl.[20][28]

Forests and green areas

Degradation of forest areas

Tlalpan has some of the largest forested lands within the Mexico City limits, with over 80% of this borough officially declared to be in conservation.[18] However, only four percent of the borough is considered to be unharmed ecologically.[29] The areas most affected by human activity are at the foot of the Xitle and Xictontle volcanos. The forest under protection in the borough equals 30,000 hectares but it is protected by only thirty-eight forest rangers, each with a territory of about 1,000 hectares of forest, canyons and volcanic areas. Three are provided by the Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente, fifteen from the Comisión de Recursos Naturales of Mexico City and twenty by the borough itself. These rangers work against illegal loggers, settlers and drug traffickers, who are often armed. The three main problems in the protected areas is illegal logging, the dumping of trash and rubble, squatting, and the theft of volcanic rock (for building materials). Most of the time, all the rangers can do is report the illegal activity to federal authorities but response is spotty.[29]

The major problem is illegal settlements. In all of Mexico City there are over 800 illegal settlements which have some official recognition and occupy almost 60% of lands considered to be protected. These areas may hold as many as 180,000 residents who lack basic services,[18] and cause grave ecological damage.[30] These settlement make trees disappear and furthers urban sprawl.[18] Erosion in conservation areas impedes aquifer recharge and disrupts the flow of surface water.[30]

In Tlalpan, settlements are in Ajusco Medio, Pedregales and Padierna, where the mountainous terrain and/or volcanic rock severely limits the ability to provide services, often leading to residents creating septic pits.[18] Since 2003, illegal settlements in Tlalpan have grown from 148(peligra), to 191 settlements that the government recognizes the existence of.[18] Many settlements have occurred because communal owners of ejidos have illegally sold parts of their land at cheap prices to settlers on the outskirts of the city proper.[30] Most illegal building is done by the very poor but there are also cases in which those which money illegally take over large sections of land for their own use.[31] Illegal settlements have been made by individual families but increasingly developers are working to build illegal settlements in protected areas as well, by buying land and creating subdivisions with services, hoping to fix things with authorities later.[14] In the early 2000s, the borough conducted over 125 operations to evict illegal settlements, dismantling over 440 housing units, but since 2005, the borough no longer has the authority to do this.[29] Many of these illegal settlements seek and then get court orders prohibiting their removal and demanding services, first potable water then drainage.[18]

To moderate the damage, there have been both public and private reforestation efforts. In 2005, forty families worked to plant 1,000 new trees in the Bosque de Tlalpan as part of an annual event sponsored by ecological associations such as Cultura Integral Forestal and Ciencia Cultura y Bosques. This annual event takes place in early July during the beginning of the rainy season and has been repeated for over twenty years. The event was initially sponsored by the Cultura Integral Forestal, made up of principally ex employees of the Loreto y Peña Pobre paper factory. Replanting efforts are focused on the main mountains of the Bosque de Tlalpan as well as the Tenantongo Valley in the same forest, planting mostly holm oak and ash trees. The annual effort has reforested over 1,500 hectares, using seeds encased in a clay ball designed to protect the seed and allow its germination. However, reforestation efforts have not been able to keep up with the deforestation of much of the borough.[32]

Parque Nacional Cumbres del Ajusco

This is a national forest which covers much of the Sierra de Ajusco and Chichinautzin mountain ranges that separate Mexico City from the states of Morelos and the State of Mexico. A portion of this forest is located in the borough of Tlalpan, as well as Milpa Alta and Xochimilco. Much of the range consists of volcanic cones, almost all dormant, with the most prominent being Xitle. Depending on altitude, the climate ranges from temperate to cold, with all but the highest elevations covered in mostly pine forests. In winter, the highest peaks occasionally are covered in snow.[33]

Bosque de Tlalpan

The Bosque de Tlalpan, also called the Parque Nacional Bosque de Pedregal, is fully surrounded by urban area, just south of the Anillo Periférico and between the highways heading to Cuernavaca and to Picacho-Ajusco. The Bosque de Tlalpan is filled with pines, oyamel fir, cedars, oaks and eucalyptus trees, which grow on a solidified lava bed. Wildlife includes eagles, falcons, squirrels and the Mexican mouse opossum. It has been open to the public since 1968. It has parking, restaurants and food stalls in cabins, playgrounds its own Casa de Cultura or cultural center.[34]

One of the attractions in the park is the Tenantono Pyramid, which is located in a remote area of the park.[1] Better known is the old Casa de la Bombas. This is an early 20th-century structure originally built in Colonia Condesa, Tlalpan to house a pump used to extract water from the ground. It ceased being a pump station in 1940 and laid vacant until 1975, when it was disassembled and moved to the Bosque. However, it was not reassembled until 1986 as part of a larger structure which now serves as a “Casa de Cultura” or cultural center. The façade of the center is made of volcanic stone called “chiluca” in French style, which was popular when it was originally built. The additions combine modern and Neoclassical elements but the interior is completely modern. The main areas are the gallery and the forum which host exhibitions and other events. There are also a number of workshops for dance, drama, music, literature and other arts. It is also the home of the Orquesta Juvenil de Tlalpan (Youth Orchestra of Tlalpan) .[35]

Other parks

Fuentes Brotates de Tlalpan is a national park with an area of about one km2 running alongside a small canyon. It has a small lake and its own Casa de Cultura (cultural center). It has problems with trash and its ecosystem is heavily damaged, although there a number of large Moctezuma cypress trees.[36]

The Parque Ecológico Loreto y Peña Pobre is located on what were the lands of a former paper factory and extends over 21,000m2.[37] This factory, called Loreto y Peña Pobre, was built in the late 19th century (a time called the Porfiriato in Mexico) when many factories and other infrastructure was built in this area.[2] The paper factory shut down in the 20th century, and its main building eventually became a mall, called the Plaza Inbursa (formerly Plaza Cuicuilco), which is known for its various entertainment options such as restaurants and movie theaters.[1][5] In 1989, the rest of the lands were converted into this ecological park. It contains a model house showing alternative technologies designed to avoid environmental damage.[1][2] Workshops are offered for children at the site, as well as restaurants serving organic food.[7]

The Parque Juana de Asbaje was established in 1999, on the site of a former psychiatric hospital on land measuring 17,000m2. It has green areas along with a bookstore selling coloring books of pre-Hispanic deities for children and replicas of archeological objects.[7][38] In 2005, the area generated controversy as the borough sought to relocate the Luis Cabrera Library. Residents initially objected, stating that it would develop too much of what is legally public space. However, later studies found that the land was not originally part of the public land grant, and the expanded library would be beneficial to the community. It was then built and has a collection of 11,000 books.[38][39]

The Parque Ecologico Ejidal San Nicolás Totolapan is located by the semi-independent rural village of the same name covering over 2,000 hectares. It contains an important reserves of tree species such as pine, oyamel fir, white cedar and holm oak, as well as meadows. It is home to eighty-two species of animals, many of which are migratory species from the United States and Canada. It is open to the public for hiking, skiing, camping, mountain biking and horseback riding.[37]

History

The first major population center in this part of the Valley of Mexico was Cuicuilco, which was populated as early as 1000 BCE. The current site contains an unusual circular pyramid, and is believed to mimic one of the volcanoes in the area. Cuicuilco was destroyed by a volcanic eruption from Xitle in 100 CE, whose lava flow eventually covered much of the south of the Valley of Mexico, creating what is now called the Pedregales del Sur as well as numerous caves and caverns. This also created areas with rich volcanic soil which would allow for agriculture and repopulation 600 years later.[2][4]

However, the area would not have another major city state, and eventually it was dominated by the Aztecs from Tenochtitlan by the 15th century. It is from their language, Nahuatl, that the name of Tlalpan, would come to be used for the largest village in the area. It means “over the earth” and refers to roads that converged here, linking Tenochtitlan with points south. The borough's glyph or symbol is the one given to the historic center by the Aztecs, a footprint over a symbol for clay soil.[4]

The area come under control of the Spanish after the fall of Tenochtitlan, and the village's name was changed from Tlapan to Villa de San Agustin de las Cuevas in 1645. San Agustin is the area's patron saint, and the name of the parish church built by the Dominicans in the early 16th century. The last part means “of the caves,” referring to the many caves and caverns formed in the area by an eruption of the Xitle volcano in 100 CE.[1][4] Initially, this area south of the Valley of Mexico was part of lands administered by authorities in Coyoacán.[4] During the colonial period, the old village of Tlalpan was a modest farming village, known for its orchards and extensive forests. The latter made it attractive as a retreat for the wealthy of Mexico City.[2] These elite established country homes and haciendas, which eventually became the economic base of the area.[1] By the 18th century, the village of Tlalpan was large enough to be an ecclesiastical center.[4]

After Independence, the Constitution of 1824, divided Mexico into states, with the area around Mexico City separated as a Federal District. However, the Tlalpan area was initially part of the then very large State of Mexico, which surrounded Mexico City. Tlalpan became the capital of the State of Mexico from 1837 until 1855, when the area was incorporated into the Federal District.[1] U.S. troops passed this way in 1847 on the road to Coyoacán where they fought Mexican troops at the Battle of Churubusco .[6]

After this war, President Antonio López de Santa Anna, expanded the Federal District south over Tlalpan to the southern mountains to make the Federal District more defensible. The village of Tlalpan became the head of what was then called the Southern Prefecture.[4] Foreign troops passed through here again during the French Intervention in Mexico. Mexican opponents of this invasion in the village were hung at the “Arbol de los colgados” in the central plaza or square.[6]

The latter decades are marked by industrialization. In the 1860s and 1870s varies types of modern infrastructure was introduced including telegraph (1866), railroad (1869) and the first long distance telephone in Mexico in 1878.[4] During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, (known as the Porfirato), various factories were established in the area including the then well known paper factory called Loreto y Peña Pobre.[2] Today, the site of this factory is an ecological park.[2] However, the village itself remained relatively untouched, filled with cobblestone streets and haciendas owned by the wealthy and filled with orchards growing apples, plums and more.[4] No battle of the Mexican Revolution occurred here, but Zapatista troops passed through, allowing for a historic meeting between Emiliano Zapata and Francisco Villa in Tlalpan.[2]

The borough of Tlalpan was created in 1928, when the Federal District of Mexico City was reorganized into 16 administrative parts called delegaciones (boroughs).[40] At that time, the area was still very rural showing little influence from then-fast growing Mexico City. One reason for this was the area called the Pedregal, the old hardened lava flow from the Xitle volcano on much of the north end of the borough. This made development of much of the borough impossible until the mid-20th century. With the construction of the Jardines de Pedregal by Luis Barragán and the Ciudad Universitaria by Mario Pani, the city began to grow in that direction.[5] The urban sprawl of Mexico City began to reach Tlalpan centero in the middle of the 20th century.[2]

For the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, two facilities were constructed in the delegation. Both were housing facilities for athletes called Villa Olimpica and Villa Coapa, which were turned into permanent houses after the games ended.[4] In the 1990s, borough authorities warned that there was no more space in Tlalpan suitable for development and that preservation of the ecological areas needed to be primary as most of the territory is mountainous, with delicate forests and meadows. However, illegal settlements in conservation areas have continued the advance of urban sprawl into ecologically sensitive and protected areas. Most of these families are poor and the lack of living space pushes them into these areas where there are no services.(mancah) The advance of urbanization means the loss of protected areas and the loss of environmental services provided by the city government. It also increased the demand for borough services such as water, sewerage and roads, despite environmental regulations.[18]

Culture and recreation

The Festival Ollin Jazz Tlalpan Internacional is a series of concerts which has hosted artists such as Enrique Neri, Eugenio Toussaint, Agustín Bernal, Bill McHenry, Brian Allen and Héctor Infanzón. The annual event takes place at the Multiforo Ollin Kan and other venues in the borough.[7]

Six Flags México, the largest theme park in Latin América, is located in Tlalpan. This park is the most popular recreation center in the city and has numerous roller coasters, rides and shows.

Just outside the archeological zone of Cuicuilco is the Centro Cultural Ollin Yoliztli (Movement and Life), where professional classes in music and dance are offered. Its concert hall is one of the sites of the Philharmonic Orchestra of Mexico City. There is another smaller hall dedicated to chamber music as well as galleries for exhibitions.[1]

In the Torre de Telmex (Telmex Tower) the Soumaya Museum was inaugurated in 1998, which features a collection of 19th century sculpture including works by Antonio Rosseti, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Auguste Rodin and Dominico Morone. Soumaya also holds temporary exhibits such as one called “Sanctuarios de lo intimo” which featured more than 600 miniature portraits and reliquaries in 2005. Nearby is the Mercado de Muebles Vasco de Quiroga furniture market where items such as bedroom sets, armoires, bookcases, tables and more are both made and sold.[1]

The borough has sponsored graffiti artists to paint certain public areas such as on and under bridges. The goal is to divert said artists away from illegally defacing property and creating murals and encouraging more talented prospects to more formal training. These graffiti murals have had themes such as the war in Iraq and can be seen at intersections as Insurgentes/Renato Leduc and Calzada Tlalpan/Viaducto Tlalpan as well as on the highway leading to Cuernavaca. The borough has also encouraged the creation of formal graffiti “guilds” to work with authorities on projects.[41]

In 2006, the borough constructed a public pool facility in Colonia Heroes de Padierna. The semi-Olympic sized pool is part of a sports facility that promotes sustainable development; the pool is solar heated. Heroes de Padierna is a lower-class neighborhood and the pool is aimed at attracting children and youths, charging only a small fee, in order to provide alternative recreation and sporting opportunities for families with few resources. The pool was built at a cost of 10,500,000 pesos with another million spent creating a soccer field alongside.[42]

Education

Post-secondary education

Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education, Mexico City is physically small, densely packed campus that is divided into two parts. In one are the academic and administrative facilities, and in the other are the sports facilities.[43] The design of its buildings reflect the various architectural styles that exist in Mexico City from the 17th to the 20th centuries., and is designed to reflect the historic center of this city.[44] The campus offers programs and degrees from the high school/preparatory level to the doctorate level. Most university and graduate school programs focus on the sciences and technology, with a number of business and legal programs. The campus also sponsors research programs in the applied sciences as well as recreational and counseling programs for its students.(campus p19) The campus was founded in 1973 and was originally located in downtown Mexico City.[45]

When the campus had grown sufficiently, land in the southern part of the city was purchases and a new campus built there in 1990. Since then the campus has grown with new programs and new installations.[46] In 2004, the campus and borough authorities signed an agreement to provide online preparatory education open to the public run as a joint venture between ITESM and the borough. The online program is meant to solve some of the problems with providing educational opportunities to the more rural areas of the borough such the communities of Ajusco Medio and Ajusco Alto. In addition, to the online resources, students from the campus can also complete their social service requirement for graduation by tutoring in rural schools in the borough.[47]

One of the most successful of Universidad del Valle de Mexico’s campuses is in the borough. In 2004, UVM expanded its campus and accommodates over 8,000 students. It offers over 25 bachelor's degrees in areas such as law, education, architecture, mechanical engineering and accounting as well as seven master's degrees. The campus contains 154 classrooms, 2 large lecture halls, over 12 computer labs, and a central library with book and digital divisions. The campus also offers sports and other recreational facilities for students.[48]

Primary and secondary schools

Of the 619 schools in the borough, 475 are pre-schools and primary schools. Ninety-seven are technical schools, and forty-seven are academic high schools or preparatory. Only 2.8% of the population over the age of fifteen is illiterate.[49] Educationally, there are as many as ten areas of the borough where the lack of education is considered to be critical, mostly in the very rural isolated areas such as Ajusco Medio and Ajusco Alto areas.[47] One effort to provide better education to the rural area is the first Preparatoria de los Pueblos of Tlalpan. It is public preparatory school was constructed in the Topilejo on a 2.5 hectare site donated by the village. The borough signed agreements with various universities such as UNAM, UAM and IPN to help provide teaching staff.[50]

National public high schools of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) Escuela Nacional Preparatoria include:

- Escuela Nacional Preparatoria 5 "José Vasconcelos"[51]

Public high schools of the Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal (IEMS) include:[52]

- Escuela Preparatoria Tlalpan I "Gral. Francisco J. Múgica"

- Escuela Preparatoria Tlalpan II "Otilio Montaño" in San Miguel Topilejo

International schools:

- Tlalpan campus of Peterson Schools (in San Andrés Totoltepec)[53]

- Formerly the British American School[54]

Other private schools:

- Colegio Alejandro Guillot[55]

- Colegio Franco Español (CFE)[56]

- Colegio Madrid[57]

- Colegio México Bachillerato[58]

- Colegio O'Farrill[59]

- Instituto Escuela del Sur (IE)[60]

- Colegio Princeton middle and senior high school campus[61]

- Colegio Williams Campus Ajusco[62]

- La Escuela de Lancaster[63]

- The Campus Yaocalli (Centro Escolar Yaocalli), for girls, of the Universidad Panamericana Preparatoria[64] is located in Colonia Miguel Hidalgo, Tlalpan.[65]

- Colegio Europeo Robert Schuman[66]

Economy

Tlalpan accounts for 6.8% of Mexico City's workforce. Most are employed in services (48.5%), followed by commerce (25.1%) and manufacturing (15.8%). The borough accounts for 4.4% of Mexico City's GDP, mostly from services (68.6% of the borough GDP), transportation and commerce. The borough accounts for 13.3% of Mexico City's rural economy (agriculture, forestry etc.) producing staple crops such as corn and beans as well as fruits (apples, peaches, etc.) and cut and uncut flowers. Livestock percentages of higher producing 28% of cattle, 23.2% of pigs and 66.9%.[49] There have been efforts by the city tourism agency to bring more tourism to the borough, especially to Tlalpan center. One proposal is to have the Turibus tour bus system include a stop in the area. However, studies and neighborhood groups have express concerns about the possibility of this leading to deterioration of the area.[21]

Cuicuilco

Cuicuilco is the site of the first large-scale ceremonial center in the Mexican Plateau and one of oldest of any size in the Americas, with occupation starting around 1000 BCE. Cuicuilco means “place of hieroglyphics” in Nahuatl. The most important structure of the site is the Gran Basamento Circular or “Great Circular Base” which has characteristics typical for the Pre-Classic period in Mesoamerican chronology (800BCE to 150AC). There are two access ramps on the east and west sides aligned with the sun on the equinoxes. Today, still on these days, many visitors come dressed in white. Eruptions from the nearby Xitle volcanos destroyed the center and its population relocating to other parts of the Valley of Mexico. These same eruptions covered much of the south of the Valley of Mexico, created the rock bed known as the Pedregales del Sur, which cover parts of Tlalpan. There is a site museum which features small anthropomorphic figures.[1][2]

Villa Olimpica

Near Cuiculco there is the Villa Olímpica which was constructed in 1968, and a zone with sculptures called the Ruta de la Amistad (Friendship Route), created for the Cultural Olympics of 1968.[5] The Villa Olympica, along with Villa Coapa, were housing complexes for athletes curing the 1968 Olympic Games, which were subsequently converted into lower class housing afterwards.[4] The Villa Olympica also contains sporting facilities built at the same time, which currently serve 1,500 visitors per day. In 2003, these faculties were rehabilitated by the Federaciones Mexicanas de Atletismo y de Deportes en Silla de Ruedas and the borough. Some of these include the Olympic track and the indoor gymnasium.[67]

The area also hosts one of Mexico City's artificial beaches, called the Playa Villa Olympica. On busy days, this beach can receive as many as 5,000 visitors, requiring workers to go through the beach area every two hours just to pick up garbage. However, water quality in the various pools tends to suffer greatly during peak times.[68]

The Pueblos area

The origins of the pueblos comes from the colonial period, when authorities worked to group dispersed bands of indigenous into villages centered around a church. This allowed them more control over the population and to regulate the economy. The pueblos in Tlalpan were mostly founded in the 16th century. In the most rural areas of Mexico City, some of these pueblos still exist intact. In Tlalpan, these include San Pedro Mártir, San Andrés Totoltepec, San Miguel Topilejo, San Miguel Xicalco, Parres el Guarda, Magdalena Petlacalco, San Miguel Ajusco and Santo Tomás Ajusco. The last two are often referred to together as “the two Ajuscos.”[19]

The name Petlacalco means “house of palm mats.” It was one of the first villages established on the slopes of the Ajusco Mountain. It took the prefix of Magdalena to honor Mary Magdalene, as patron saint. The town is centered on a church built in 1725. It has one nave divided into three sections and a presbytery with a Neoclassical altar. On this altar is an image of Mary Magdalene which dates from the 18th century. The wooden main doors of the church were constructed much later, 1968. The town's saint's days are 1 January and 22 July. It also has a patron an image of the Señor de la Columna, an image of Jesus as he was tied to a post for flogging. This image is brought out for procession and other honors on the first Friday of Lent. The village is surrounded by communal lands in which there are forests, surface water and landscapes that the residents are tasked with conserving. It is the site of El Arenal, a sand dune formed by the ash of the Xitle volcano. The area attracts families and other visitors who climb dunes.[69]

Parres el Guarda was founded in the middle of the 19th century as a rail town, when the line connecting Mexico City and Cuernavaca was built. Parres was an important stop for both passengers and freight along this line. The community was founded on lands that belonged to the Juan de las Fuentes Parres Hacienda, giving the town its name. Today, one can still see the ruins of the old hacienda main house. Its economy currently is based on the cultivation of animal feed and is an important producer of this product. It is also known for the sheep meat which is most often used in the preparation of barbacoa in the Mexico City area. Its patron saint is the Virgin of Guadalupe, celebrated on 12 December traditionally with the Chinelos dance, fireworks, cockfights and more.[70]

San Andrés Totoltepec was founded in 1548, when the lands in this area were taken from their indigenous owners and the residents moved to the new village, with its church whose current structure was built in the 18th century. In 1560, the lands were returned for communal possession of the village. The name Nahuatl name Totoltepec mean “turkey hill.” Over half of the village's residents today are dedicated to commerce, one fifth to industry and only a tenth to agriculture and livestock. Of the land surrounding it, 40% is unsuitable for farming due to volcanic rock. The center of the town is its church, dedicated to the Apostle Andrew. It has one nave, choir and presbytery with an altarpiece from the 18th century. This altarpiece has paintings of Christ receiving baptism and the appearances of the Virgin of Guadalupe. At the top, there is an image of Andrew, sculpted in wood. The east wall has a paintings from the 18th century with an image of Saint Isadore the Laborer, along with an image of the Virgin Mary in wood and an image of Christ in cornstalk paste.[71]

San Miguel Ajusco was founded in 1531 by an indigenous leader named Tecpanécatl under the auspices of the Spanish. The center of the village then and now is church founded in dedicated to the Archangel Michael. According to local tradition, this angel has appeared to the village three times. The church's current structure dates to 1707, with an 18th-century wood sculpture of the Archangel in the presbytery. The main portal is made of sandstone with a high relief of Saint James the Greater which as has an inscription in Nahuatl. The archangel is commemorated on 8 May and 29 September, with Chinelos, rodeo and other traditional events. Near the village, there is an area called Las Calaveras at the foot of the Mesontepec Hill, which has a small pyramid called Tequipa.[72]

San Miguel Topilejo was founded by Franciscan friars under Martín de Valencia. Topilejo is from Nahuatl and means “he who wields the precious scepter of command”. One of the main attractions is the San Miguel Arcangel Church on the town's main square. This church was built in 1560, with the cupola redone in the 18th century and the tower finished in 1812. The atrium is built over what probably was a pre-Hispanic platform. It was declared a historic monument by the federal government in 1932. The town's economy is mostly based on farming, producing crops such as vegetables, houseplants, oats and corn, with forty percent of the population dedicated to this. The town and church is dedicated to the Archangel Michael who is honored each 29 September with Aztec dance, Chinelos, wind band and other folk and popular dance. The town also hosts the annual Feria del Elote (Corn Fair) which began in 1985.[73]

San Miguel Xicalco is located just off the Mexico City-Cuernavaca highway. Xicalco comes from Nahuatl and means “house of grass” or “house of plants.” San Miguel is in honor of the Archangel Michael, the patron saint, who is said to have appeared here. The center of the small community is a chapel from the 17th century, which has one nave, of three sections and a presbytery. The image of Michael inside is made of cornstalk paste. Michael is honored twice a year here, on 8 May, when he is said to have appeared and on 29 September, his usual feast day. These days are traditionally celebrated with mole rojo (red mole sauce), tamales, Chinelos, other indigenous and folk dance as well as traditional music. Another story from the area is that during the Mexican Revolution, Zapatista troops took control of the small church to use as a headquarters. Today, there is a small cannon which is said to have been left by these troops.[74]

San Pedro Mártir is believed to have been founded by Franciscan friars during the early colonial period, with its chapel around the end of the 17th or early 18th century. This chapel has a simple portal with little decoration. The entrance arch has a niche with a sculpture of Saint Peter of Verona, the patron saint, with a cross at the crest. This chapel has a single nave with a vault covering it. Above the choir area, there is an Austrian eagle and a medallion with an image of the Archangel Michael. There is also an 18th-century sculpture of Saint Peter of Verona. The main altar contains a crucifix which also dates from the 18th century. The feast day of the patron saint is celebrated on 29 April with traditional dances such as Santiagos, Pastores, Arreiros and Chinelos. Many residents sustain themselves on ejido lands which they gained after the Mexican Revolution, growing staple crops such as corn and beans.[75]

Santo Tomás Ajusco was founded in the early colonial period. Ajusco refers to the many fresh water springs which flow on the side of the Ajusco Mountain. The center of the town has a single nave church with a sculpture of Saint Thomas sculpted in wood, a crucifix made of ivory and an 18th-century sculpture of Saint James on horseback inside. The façade has three portals in sandstone with the center one decorated in plant motifs. The face also has three low reliefs. The atrium is paved with rock taken from the Tequipa pyramid. The feast day of the patron saint is 3 July.[76]

In 2010, the city incorporated 175 hectares of forest in the borough as areas protected by the city in the areas around San Miguel Ajusco and Santo Tómas Ajusco. One reason for this was to put an end to territorial disputes between these two communities as well as with the neighboring community of Xalatlco in the State of Mexico for seventy years. Another reason is to combat continuing illegal logging and settlements.[77]

Notable people

- Renato Leduc (1897–1986), poet and journalist

References

- Ricardo Diazmunoz; Maryell Ortiz de Zarate. (October 10, 2004). "Encuentros con Mexico / Sabores de Tlalpan" [Encounters with Mexico/Flavors of Tlalpan]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 18.

- "Conócenos" [Meet us] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Sergio Gonzalez Rodriguez (May 11, 2001). "Bajos Fondos/ Hacienda de Tlalpan" [Low Funds/Tlalpan Hacienda]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 43.

- Anayansin Inzunza (April 1, 2003). "Centro de Tlalpan: Acosada por el delito" [Tlalpan center: accosted by crime]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- Jorge Prior. "En bici, de Tlalpan a La Villa (Distrito Federal)" [On bicycle, from Tlalpan to La Villa (Federal District)] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Anibal Santiago. (September 9, 2002). "Busca Tlalpan reconocimiento" [Tlalpan seeks recognition]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 10.

- "En el corazón de Tlalpan" [In the heart of Tlalpan]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. July 24, 2009. p. 18.

- Anibal Santiago. (February 25, 2002). "Alberga cultura la Casa Frissac" [Casa Frissac houses culture]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 9.

- "Museo de Historia de Tlalpan" [Museum of the History of Tlalpan]. Sistema de Informacion Cultural (in Spanish). Mexico: CONACULTA. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Omar Garcia. (September 19, 2003). "Abren en Tlalpan Museo de Historia" [Open Museum of History in Tlalpan]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 3.

- Julieta Riveroll. (February 17, 2006). "Nace museo al aire libre" [Open-air museum is born]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 9.

- Quintanar Hinojosa, Beatriz, ed. (November 2011). "Mexico Desconocido Guia Especial:Barrios Mágicos" [Mexico Desconocido Special Guide:Magical Neighborhoods]. Mexico Desconocido (in Spanish). Mexico City: Impresiones Aereas SA de CV: 5–6. ISSN 1870-9400.

- Ricardo Rivera (October 24, 2010). "Dificulta geografía vigilancia en Tlalpan" [Geography makes vigilance difficult in Tlalpan]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- Rodolfo Ambriz. (February 21, 1998). "Inhibiran mancha urbana en Tlalpan" [Will inhibit the advance of urban sprawl in Tlalpan]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- 2010 census tables: INEGI

- "Tlalpan" (in Spanish). Mexico City: El Universal. August 26, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Roberto Morales Noble (2000). Hacia un presupuesto participativo. La experiencia en Tlalpan, Distrito Federal (PDF) (Report). Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales UNAM. Archived from the original on December 22, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2010.CS1 maint: unfit url (link) (Archive)

- Ivan Sosa (June 4, 2003). "Peligra suelo rural por las invasions" [Rural ground in danger by invasions]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- "Los Pueblos en Tlalpan" [The pueblos of Tlalpan] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Anibal Santiago. (June 20, 2001). "Reclama Tlalpan obras a DGCOH" [Tlalpan complains about works by DGCOH]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

- Alberto Acosta. (October 4, 2005). "Ponen condiciones al Turibus" [Put conditions on the Turibus]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

- "Tlalpan combate el robo de autos" [Tlalpan combats auto theft]. SDP Noticias (in Spanish). Mexico. April 14, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Arista, Lidia. "Los 8 pueblos de Tlalpan" (Archive). El Universal. September 1, 2011. Retrieved on June 2, 2014.

- Luis Fernando Reyes. (September 19, 2009). "Avanza Tlalpan en suelo verde" [Tlalpan advances over green areas]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- "Informe del Sismo del 16 de Octubre del 2005 en la Delegación Tlalpan" [Report on the quake of 16 October 2005 in Tlalpan borough] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Servicio Sismológico Nacional - UNAM. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "Detecta Tlalpan tres zonas susceptibles a sismos" [Tlalpan detects three zones susceptible to quakes]. SDP Noticias (in Spanish). Mexico. May 5, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Anibal Santiago. (March 24, 2001). "Sufren desabasto colonias en Tlalpan" [Colonias in Tlalpan suffer shortages]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 7.

- Josué Huerta (January 10, 2010). "Preparan en Tlalpan atlas de riesgo" [Tlalpan prepares risk atlas]. La Cronica de Hoy (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Alberto González. (May 28, 2006). "Faltan a Tlalpan guardabosques" [Tlalpan lacks forest rangers]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

- Arturo Paramo. (August 13, 2003). "Urgen defender Tlalpan" [Urge defense of Tlalpan]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 5.

- Rafael Cabrera. (May 24, 2007). "Padece Tlalpan por invasiones" [Tlalpan suffers from invasions]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- Nadia Sanders. (July 4, 2005). "Plantan en Tlalpan mil nuevos arboles" [Thousand new trees planted in Tlalpan]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- Jimenez Gonzalez, Victor Manuel, ed. (2009). Ciudad de Mexico Guia para descubir los encantos de la Ciudad de Mexico [Mexico City: Guide to discover the charms of Mexico City] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editorial Oceano de Mexico SA de CV. p. 71. ISBN 978-607-400-061-0.

- "Bosque de Tlalpan" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "Casa de Cultura de Tlalpan". Sistema de Informacion Cultural (in Spanish). Mexico: CONACULTA. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "Fuentes Brotantes de Tlalpan" (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Latinoamericano de la Comunicación Educativa. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Jimenez Gonzalez, Victor Manuel, ed. (2009). Ciudad de Mexico Guia para descubir los encantos de la Ciudad de Mexico [Mexico City: Guide to discover the charms of Mexico City] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editorial Oceano de Mexico SA de CV. p. 73. ISBN 978-607-400-061-0.

- Alberto Acosta. (October 25, 2005). "Amenaza construccion a parque" [Construction threatens park]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- Alberto Acosta (October 31, 2005). "Aprueban vecinos obra en el centro de Tlalpan" [Neighbors approve work in center of Tlalpan]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- "Historia de la Delegación" [History of the Borough] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Cuauhtémoc. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- Ivan Sosa. (April 25, 2004). "Convierten el graffiti en murales" [Convert graffiti into murals]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- Alberto Gonzalez. (January 8, 2006). "Construye Tlalpan alberca ecologica" [Tlalpan constructs ecological pool]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- "Mapa del Campus" [Map of Campus] (in Spanish). Mexico City: ITESM-Campus CCM. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- Campus Ciudad de México (in Spanish). ITESM-Campus CCM (1 ed.). Mexico City: Dirección de Comunicación y Mercadotecnia del Campus Ciudad de Mexico. 2008. p. 12.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Historia 1970-1980" [History 1970-1980] (in Spanish). Mexico City: ITESM-Campus CCM. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- "Historia 1990-2000" [History 1990-2000] (in Spanish). Mexico City: ITESM-Campus CCM. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- Alberto Gonzalez; Alejandro Ramos (December 15, 2004). "Impulsan convenio Tlalpan e ITESM" [Tlalpan and ITESM push accord]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- "Consolidan excelencia academica al sur de la ciudad en UVM Tlalpan" [Consolidate academic excellence in the south of the city at UVM Tlalpan]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. February 2, 2004. p. 1.

- "Delegación Tlalpan natural protegida en Tlalpan" [Tlalpan borough] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City: Government of Mexico City. Archived from the original on May 21, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2010.CS1 maint: unfit url (link) (Archive)

- Francisco Velazquez. (January 15, 2000). "Construye Tlalpan Prepa de los Pueblos" [Tlalpan constructs Prepa de los Pueblos]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- "Ubicación." Escuela Nacional Preparatoria Plantel 5 "José Vasconcelos". Retrieved on June 27, 2014. "Calzada del Hueso 729 Col. Ex-Hacienda Coapa cp. 14300"

- "Planteles Tlalpan." Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal. Retrieved on May 28, 2014.

- "Tlalpan." Peterson Schools. Retrieved on May 18, 2014. "Address: Carretera Federal a Cuernavaca Km. 24, San Andrés Totoltepec, Tlalpan, C.P. 14400 (8 minutes away from Periferico and Tlalpan – Ecological Area)."

- "Contact" (Archive). British American School. Retrieved on June 18, 2014. "BRITISH AMERICAN SCHOOL Insurgentes Sur No. 4040 Tlalpan 14000, Mexico City"

- "Mapa de ubicación." Colegio Alejandro Guillot. Retrieved on April 12, 2016. "Kinder y Primaria Av. Canal de Miramontes 3160 Col. Ex Hacienda Coapa C.P. 14300 Tlalpan D.F." and "Secundaria Rancho Camichines 19 Col. Nueva Oriental Coapa C.P. 14300 Tlalpan, D.F." and "Preparatoria Rancho Calichal 12 Col. Nueva Oriental Coapa C.P. 14300 Tlalpan, D.F."

- "Ubicación" (Body page). Colegio Franco Español. Retrieved on May 26, 2014. "PREESCOLAR - PRIMARIA Calzada México-Xochimilco 122 Col. San Lorenzo Huipulco C.P. 14370" and "SECUNDARIA - PREPARATORIA Calzada México-Xochimilco 88 Col. San Lorenzo Huipulco C.P. 14370"

- "Historia." Colegio Madrid. Retrieved on April 12, 2016. "Calle Puente No. 224 Col. Ex Hacienda San Juan de Dios C.P. 14387, Ciudad de México"

- Home page. Colegio México Bachillerato. Retrieved on April 12, 2016. "Bordo 178 Col. Vergel del Sur C.P. 14340, México D.F."

- "Ubicación." Colegio O'Farrill. Retrieved on April 13, 2016. "Carretera Picacho-Ajusco Km. 5 Col. Ampliación Miguel Hidalgo, C.P. 14250 Del. Tlalpan, México, D.F."

- "¿Quiénes somos?" Instituto Escuela del Sur. Retrieved on June 1, 2014. "Prolongación Corregidora 592, Col. Miguel Hidalgo, Delegación Tlalpan, C.P. 11410, México, D.F."

- "Campus." Colegio Princeton. Retrieved on April 12, 2016. "Secundaria / Bachillerato Camino al Ajusco 203 Col. Heroes de Padierna C.P. 14200 México D.F."

- "CAMPUS." Colegio Williams. Retrieved on April 15, 2016. "Campus Ajusco Calle de la Felicidad S/N Col. San Miguel Ajusco Deleg. Tlalpan México D.F., C.P. 14700"

- "How to find us." La Escuela de Lancaster. Retrieved on April 12, 2016. "Plantel Diligencias Prolongación 5 de mayo #67, Colonia San Pedro Mártir, Delegación Tlalpan, CP 14650, México DF" and "Plantel Rey Yupanqui Rey Yupanqui #46,Colonia Tlalcoligia, Delegación Tlalpan, CP 14430, México DF"

- Preparatoria." Universidad Panamericana Preparatoria. Retrieved on April 18, 2016.

- "Conócenos." Universidad Panamericana Preparatoria Femenil. Retrieved on April 18, 2016. "Cerrada Ciudad de León No. 54, Colonia Miguel Hidalgo Delegación Tlalpan, C. P. 14260, México, D. F."

- Home. Colegio Europeo Robert Schuman. Retrieved on December 5, 2017. "Acceso a P. Militar 15, Col. Nvo. Renacimiento Axalco, 14408 Tlalpan, CDMX Colegio Europeo de México Robert Schuman"

- Ivis Aburto (May 27, 2003). "Reviven Villa Olimpica" [Revive Villa Olimpica]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- Sergio Fimbres. (April 5, 2007). "Saturan capitalinos su playa artificial" [Residents of the capital saturate artificial beach]. Palabra (in Spanish). Saltillo, Mexico. p. 14.

- "Magdalena Petlacalco" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "Parres El Guarda" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "San Andrés Totoltepec" [The pueblos of Tlalpan] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "San Miguel Ajusco" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "San Miguel Topilejo" [The pueblos of Tlalpan] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "San Miguel Xicalco" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "San Pedro Mártir" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "Santo Tomás Ajusco" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- "Crece la reserva natural protegida en Tlalpan" [Natural protected reserve grows in Tlalpan] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Tlalpan. November 16, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mexico City — Tlalpan. |

- (in Spanish) Delegación Tlalpan Official site

- Images of Tlalpan

- (in Spanish) Information about Tlalpan, and its political and ecological developments

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tlalpan Municipality. |