Santa Cruz de la Sierra

Santa Cruz de la Sierra (Spanish: [ˈsanta ˈkɾuz ðe la ˈsjera];[2] lit. "Holy Cross of the Mountain Range"), commonly known as Santa Cruz, is the largest city in Bolivia and the capital of the Santa Cruz department.[3]

Santa Cruz de la Sierra | |

|---|---|

Autonomous city and municipality | |

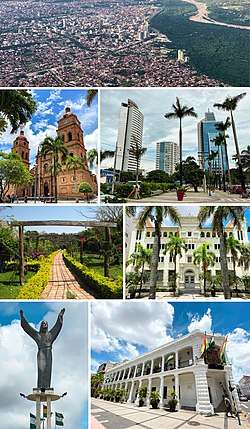

Clockwise, from top: Aerial view of Santa Cruz, buildings in the Equipetrol neighborhood, the Casa del Pueblo, the Autonomous Municipal Government House, the Cristo Redentor of Santa Cruz, the Güembé bioresort and the Cathedral Basilica of St. Lawrence. | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Santa Cruz de la Sierra Location within Bolivia  Santa Cruz de la Sierra Santa Cruz de la Sierra (South America) .svg.png) Santa Cruz de la Sierra Santa Cruz de la Sierra (Earth) | |

| Coordinates: 17°48′S 63°11′W | |

| Country | |

| Department | |

| Province | Andrés Ibáñez |

| Municipality | Santa Cruz de la Sierra |

| Founded | February 26, 1561 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Autonomous Government |

| • Mayor | Percy Fernandez |

| Area | |

| • Autonomous city and municipality | 1,345 km2 (519 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 400 m (1,300 ft) |

| Population (2012 Census) | |

| • Urban | 1,441,406 |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (BOT) |

| Area code(s) | (+591) 3 |

| HDI (2001) | 0.739 Second place in Bolivia– high[1] |

| Website | www |

Situated on the Pirai River in the eastern Tropical Lowlands of Bolivia, the Santa Cruz de la Sierra Metropolitan Region is the most populous urban agglomeration in Bolivia with an estimated of 2.3 million population[4] in 2020, it is formed by a conurbation of seven Santa Cruz municipalities: Santa Cruz de la Sierra, La Guardia, Warnes, Cotoca, El Torno, Porongo, and Montero[5].

The city was first founded in 1561 by Spanish explorer Ñuflo de Chavez about 200 km (124 mi) east of its current location, and was moved several times until it was finally established on the Pirai River in the late 16th century. For much of its history, Santa Cruz was mostly a small outpost town, and even after Bolivia gained its independence in 1825 there was little attention from the authorities or the population in general to settle the region. It was not until after the middle of the 20th century with profound agrarian and land reforms that the city began to grow at a very fast pace.

The city is Bolivia's most populous, produces nearly 35% of Bolivia's gross domestic product, and receives over 40% of all foreign direct investment in the country. This has helped make Santa Cruz the most important business center in Bolivia and the preferred destination of migrants from all over the country.[6]

History

Pre-Columbian era

Like much of the history of the people of the region, the history of the area before the arrival of European explorers is not well documented, mostly because of the somewhat nomadic nature and the absence of a written language in the culture of the local tribes. However, recent data suggests that the current location of the city of Santa Cruz was inhabited by an Arawak tribe that later came to be known by the Spanish as Chané. Remains of ceramics and weapons have been found in the area, leading researchers to believe they had established settlements in the area. Among the few known facts of these tribes, according to accounts of the first Spanish explorers that came into contact with the Chané, are that they had a formal leader, a cacique, called Grigota for several years but his reign came to an end after one of the several Guarani (Chirigano) incursions in the area.

Early European incursions and founding of the city

.svg.png)

The first Europeans to set foot in the area were Spanish conquistadores from the recently created Governorate of New Andalusia that encompassed the territories of present-day Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Chile.

In 1549, Captain General Domingo Martinez de Irala became the first Spaniard to explore the region, but it was not until 1558 that Ñuflo de Chaves, who had arrived in Asuncion in 1541 with Alvar Nuñez/Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, led a new expedition with the objective of settling the region. After discovering that a new expedition from Asuncion was already underway, he quickly traveled to Lima and successfully persuaded the Viceroy to create a new province and grant him the title of governor on February 15, 1560. Upon returning from Lima, Chaves founded the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra (Holy Cross of the Hills) on February 26, 1561, 220 km (137 mi) east of its present-day location, to function as the capital of the newly formed province of Moxos and Chaves. The settlement was named after Chaves's home town in Extremadura, where he grew up before venturing to America.

Shortly after the founding, attacks from local tribes became commonplace and Ñuflo de Chaves was killed in 1568 by Itatine natives. After Chaves's death, the conflicts with the local population as well as power struggles in the settlement forced the authorities in Peru to order the new governor, Lorenzo Suarez de Figueroa to relocate the city to the west. Many of the inhabitants, however, chose to stay behind and continued living in the original location. On September 13, 1590 the city was officially moved to the banks of the Guapay Empero river and renamed San Lorenzo de la Frontera. Nevertheless, the conditions proved to be even more severe at the new location forcing the settlers to relocate once again on May 21, 1595. Although this was the final relocation of the city, the name San Lorenzo continued to be used until the early 17th century, when the settlers who remained behind in Santa Cruz de la Sierra were convinced by the colonial authorities to move to San Lorenzo. After they moved the city was finally consolidated in 1622 and took its original name of Santa Cruz de la Sierra given by Ñuflo de Chaves over 60 years before. Remnants of the original settlement can be visited in Santa Cruz la Vieja ("Old Santa Cruz"), an archaeological site south of San José de Chiquitos.[7][8]

Colonial Santa Cruz and revolutionary war

Over the next 200 years, several tribes were either incorporated under Spanish control or defeated by force. The city also became an important staging point for Jesuit Missions to Chiquitos and Moxos, leading to the conversion of thousands of Guaranies, Moxeños, Chiquitanos, Guarayos and Chiriguanos that eventually became part of the racially mixed population of the modern Santa Cruz, Beni, Pando and Tarija departments of Bolivia. Another important role the small town played in the region for the Spanish Empire was to contain the incursions of Portuguese Bandeirantes, many of which were repelled by the use of force over the years. The efforts for consolidating the borders of the Empire were not overlooked by the authorities in Lima, who granted the province a great degree of autonomy. The province was ruled by a Captain General based in Santa Cruz, and, in turn, the city government was administered by two mayors and a council of four people. Citizens of Santa Cruz were exempt from all imperial taxes and the mita system used in the rest of the Viceroyalty of Peru was not practiced. However, in spite of its strategic importance, the city did not grow much in colonial times. Most of the economic activity was centered in the mining centers of the west and the main source of income of the city was agriculture.

Animosity towards imperial authorities began at the turn of the 18th century when the new system of intendencias reached the new world. The seat of government was taken away from the city and moved to Cochabamba, and many of the powers delegated by the viceroyalty were now in the hands of appointees of the crown. Like in many parts of Spanish America at the time, angered by the reforms the criollos saw as a threat to their way of life, and taking advantage of the Peninsular War, the local population, led by Antonio Vicente Seonane, revolted on September 24, 1810, overthrowing the governor delegate. A junta of local commanders took control of the government in his place. The revolutionaries, as it was the case with most of the revolts in Spanish America, remained loyal to the King of Spain, while repudiating the colonial authorities until after the end of the Peninsular War.

By 1813 the city was once again under imperial control. At this time, by order of General Manuel Belgrano, the revolutionary armies of Argentina sent a small force led by Ignacio Warnes to "liberate" Santa Cruz. After his successful campaign, he assumed control of the government of the city. In a little over a year Warnes was able to gather tremendous support from the population, enlisting criollos, mestizos and natives to the revolutionary army, and allying with the revolutionary leader of Vallegrande, Alvarez de Arenales, to defeat a strong imperial force in the Battle of Florida. This victory proved to be a serious blow to Spanish forces in the region. Nevertheless, two years after the victory of Florida, imperial forces launched a new offensive in the province led by Francisco Javier Aguilera. This campaign ended with the defeat and death of Ignacio Warnes and his forces in the Battle of Pari. Triumphant, Aguilera marched into the city with orders to quell the insurrection and reinstate the Spanish governor. This proved to be a very difficult task, with several revolutionary leaders, such as Jose Manuel "Cañoto" Baca and Jose Manuel Mercado, rising up in the coming years from the city itself and elsewhere in the province. These new leaders fought colonial authorities for seven years until they finally deposed the last Spanish governor, Manuel Fernando Aramburu, in February 1825 after news of the defeat of the imperial armies in the west had reached the city.[9]

Geography

The city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra is located in the eastern part of Bolivia (17°45', South, 63°14', West) at around 400 m above sea level.[10] It is part of the province of Andrés Ibáñez and the capital of the department of Santa Cruz. The city of Santa Cruz is located not far from the easternmost extent of the Andes Mountains and they are visible from some parts of the city.

Climate

The city has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen: Aw), with an average annual temperature around 25 °C (77 °F) and all months above of 18 °C. Santa Cruz is an example of the influence of continentality (reflecting the thermal amplitude) in the tropics, without the four well-defined seasons of the year but greater deviations of temperature than other places in the coast or island.[11][12] Although the weather is generally warm all year round, cold winds called "surazos" can blow in occasionally (particularly in the winter) from the Argentine pampas making the temperature drop considerably. The months of greatest rainfall are December and January. The average annual rainfall is 1,321 mm (52 in).

| Climate data for Santa Cruz de la Sierra | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 38.1 (100.6) |

37.8 (100.0) |

39.3 (102.7) |

38.0 (100.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

35.0 (95.0) |

36.4 (97.5) |

38.4 (101.1) |

40.3 (104.5) |

38.4 (101.1) |

40.3 (104.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.2 (86.4) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

24.9 (76.8) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.4 (88.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.8 (80.2) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

24.7 (76.5) |

22.8 (73.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.3 (70.3) |

21.3 (70.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 11.6 (52.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 203 (8.0) |

134 (5.3) |

118 (4.6) |

118 (4.6) |

84 (3.3) |

73 (2.9) |

61 (2.4) |

37 (1.5) |

58 (2.3) |

108 (4.3) |

143 (5.6) |

185 (7.3) |

1,321 (52.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 14.0 | 11.1 | 12.7 | 9.4 | 11.4 | 8.6 | 6.1 | 4.0 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 9.4 | 11.9 | 111.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 79 | 78 | 73 | 65 | 64 | 67 | 72 | 77 | 74 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst[13] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

The first settlers of Santa Cruz were mainly the Native Chane people of East Bolivia followed by the Spaniards that accompanied Ñuflo de Chávez, as well as Guarani natives from Paraguay, and other native American groups that previously lived there working for the Spanish crown. Eventually, the Spanish settlers and native people of Bolivia began to mix which has resulted in the majority of the city population being mestizo. When the Spanish settlers arrived to Bolivia, Catholicism, as well as the Spanish language, were implemented onto the natives which is now why the city is predominantly Catholic and speak Spanish. Nevertheless, native religions and languages are still used by a minority of the population.[14]

It is important to point out that there is a distinction between the ethno-demographic profile of the Santa Cruz de la Sierra region, marked by the mestizo, Spanish and eastern indigenous presence, in relation to the population of the Bolivian Altiplano, western part of the country mostly Andean indigenous with a smaller mestizo and Spanish presence.

Government and infrastructure

The Centro de Rehabilitación Santa Cruz "Palmasola" is a prison located in Santa Cruz.[15]

The city is served by Viru Viru International Airport, which connects it to domestic and international destinations.

It was formerly linked with the Brazilian railway system through a line to Corumbá, Brazil.[16] This line, which was reputed to have a poor safety record, was abandoned after a highway to the Brazilian border was built in the 1980s.

Culture and food

Museums, Cultural Centers and Galleries

Santa Cruz offers an interesting circuit of cultural and art spaces, from natural history, to religious art up to the newest contemporary art. There is a young art market which is growing fast.

- Casa de la Cultura Raul Otero Reiche

- Noel Kempff Mercado Natural History Museum

- Teniente General German Busch Becerra National History Museum

- National and Regional Museum and Archive

- Guarani museum

- Cathedral Museum of Sacred Art

- Museum of Art and Archaeology

- Museum of Independence

- Manzana Uno (art center)

- Cultural Center Santa Cruz

- Cultural Center Simon I. Patiño

- Training Centre of the Spanish Cooperation

- Feliciana Rodriguez Cultural Center

- Franco German Cultural Center

- Art Gallery Axioma

- Gallery Kiosko

- Gallery Bhuo Blanco

- Guembe Biocenter

The city of Santa Cruz has benefited from a fast-growing economy for the last 15 years. Despite its rapid growth the city preserves much of its traditions and culture. This is particularly reflected in its typical foods.

The Spaniards introduced cows, poultry, rice, citrus fruits (oranges, tangerines and lemons), from southern Asia they brought sugar cane and from Africa plantains, bananas and coffee (which is cultivated in the Yungas near Buena Vista. Moreover, local dishes include native vegetables such as corn, peanuts, yuca and squash, and also local fish such as surubi and pacu.

Native spices such as urucum, and native fruits (unique to the region) such as achachairu, guapuru and guabira, add to the uniqueness of Santa Cruz rich traditional cuisine. The agricultural richness of the region allows Santa Cruz to enjoy a vast variety of flavours and ingredients. The following is a list which describes the most typical foods:

Gastronomy

Typical Foods

_03.jpg)

- Majao or Majadito (a risotto-style plate with charque, duck, or chicken meat. Served in two variations: majadito tostado or majadito batido)

- Locro (a rice and hen soup with potatoes, onion, garlic, and oregano. It is common to use chicken instead of hen, and it is eaten with a piece of boiled yuca)

- Locro carretero

- Pipian (peanut butter chicken, served with rice and cassa)

- Rapi al jugo

- Keperi

- Cogote Relleno

- Masaco (smashed plantain with charque. Also made with yuca)

- Patasca (a corn and pork soup, served with cooked yuca and chopped green onions)

- Asado or Parrillada (served with arroz con queso, cooked or fried yuca, chorizo, and salad)

Typical Drinks

- Somó (white corn-based drink, served cold)

- Chicha (sweet non-alcoholic drink made with corn and cinnamon)

Typical Pastries

- Cuñapé (yuca and cheese baked in small buns)

- Cuñapé Duro (bizcocho)

- Sonso (yuca and cheese, boiled and mixed, and then oven baked or grilled)

- Sonso pacumuto

- Tamal al Horno

- Tamal a la olla

- Empanada

- Rosca de maiz

- Pan de arroz

- Salteña

- Bizcocho de trigo

- Masaco

- Masaco de plátano (banana mixed with charque or meat)

- Masaco de yuca (yuca mixed with charque or meat)

- Masaco de queso (cheese mixed with banana or meat)

- Arepas

- Pastel de choclo (corn)

- Queque

Economy

The city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra has utility infrastructure, roads and highways, and lively shopping and business. The main sectors that drive the economy are oil, forestry companies, agribusiness, and construction. Santa Cruz contributes more than 80% of national agricultural production, and also has contributed over 35% of GDP in recent years. It also has the country's largest airport, making it an ideal city for trade shows, international events and investments.

It is noteworthy that in Santa Cruz there is considerable investment in the construction sector (office buildings and houses), business (large supermarket chains and mass consumption centers), the health sector (high-tech private clinics), the fashion industry, national and international shows, agribusiness, hospitality and cuisine (highly developed), not to mention many private universities. The airline AeroSur had its headquarters in Santa Cruz.[17] The airline ceased operations in May 2012 and has been replaced by Boliviana de Aviación, which flies from Santa Cruz to Miami, Madrid, Buenos Aires, Salta and São Paulo. Bolivia's largest Shopping mall, the Ventura Mall is located in the city of Santa Cruz.

Hotels

Santa Cruz de la Sierra has one of the best hotel infrastructures in the country. Some of the hotels in the city include Los Tajibos Hotel, Hotel Toborochi, Hotel Buganvillas, Marriott Hotels & Resorts Santa Cruz de la Sierra and Hotel Camino Real.

Twin towns – Sister cities

Santa Cruz de la Sierra is twinned with:

|

References

- "IDH Municipios Bolivia part 201" (PDF). Bivica.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- In isolation, Cruz and de are pronounced [kɾus] and [de].

- "National Statistics Institute. Population Projections by Department and Municipality". INE. Archived from the original on 2016-10-09. Retrieved 2017-03-02.

- "Bolivia: Proyecciones de Población según Departamento y Municipio, 2012-2020". INE Bolivia (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. Archived from the original on 2020-06-01. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Ocho municipios de la región metropolitana de Santa Cruz se unen y demandan atención económica al Gobierno nacional | EL DEBER". eldeber.com.bo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- "The Contributions of Santa Cruz to Bolivia (Spanish only)" (PDF). CAINCO. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2011-09-09.

- Nino Gandarilla (1995). Santa Cruz en los umbrales del desarrollo (PDF). Santa Cruz de la Sierra: Proyecciones RRPP. p. 41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

- Archived 2012-03-29 at the Wayback Machine Fundación de Santa Cruz de la Sierra: una historia épica del Siglo XV, El Mundo, 09/11/2011

- Nino Gandarilla (1995). Santa Cruz en los umbrales del desarrollo (PDF). Santa Cruz de la Sierra: Proyecciones RRPP. p. 46. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2018-03-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Santa Cruz, Bolivia Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 2019-02-25. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- Abrahamczyk, Stefan; Kluge, Jürgen; Gareca, Yuvinka; Reichle, Steffen; Kessler, Michael (2011-11-02). "The Influence of Climatic Seasonality on the Diversity of Different Tropical Pollinator Groups". PLoS ONE. 6 (11): e27115. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027115. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3206942. PMID 22073268.

- "Klimatafel von Santa Cruz, Prov. Santa Cruz de la Sierra / Bolivien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Al Margen de mis Lecturas, by Marcelo Terceros Banzer. Published September 1998

- Meilhan, Pierre. "Dozens killed in Bolivia prison fire, brawl Archived 2013-08-24 at the Wayback Machine." CNN. August 24, 2013. Retrieved on August 24, 2013.

- Eisenberg, Daniel (1987). "Bolivia". Journal of Hispanic Philology. 11 (3): 193–198.

- "Contact Information Archived 2010-01-30 at the Wayback Machine." AeroSur. Retrieved on February 27, 2010.

- "Edinburgh – Twin and Partner Cities". 2008 The City of Edinburgh Council, City Chambers, High Street, Edinburgh, EH1 1YJ Scotland. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- "Twin and Partner Cities". City of Edinburgh Council. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

Further reading

- Eisenberg, Daniel (1987). "Bolivia". Journal of Hispanic Philology. 11 (3): 193–198.

- Gutsch, Jochen-Martin, "Im Labyrinth der Unordnung" [In the Labyrinth of Disorder]. Der Spiegel. 5 December 2005, pp. 144–50.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Santa Cruz, Bolivia. |

- Official city government site

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.