Monumento a la Revolución

The Monument to the Revolution (Spanish: Monumento a la Revolución) is a landmark and monument commemorating the Mexican Revolution. It is located in Plaza de la República, near to the heart of the major thoroughfares Paseo de la Reforma and Avenida de los Insurgentes in downtown Mexico City.

| Monument to the Revolution | |

|---|---|

| Native name Spanish: Monumento a la Revolución | |

| |

| Type | Monument |

| Location | Cuauhtémoc borough, Mexico City, Mexico |

| Built | 1910 - 1938 |

| Architect | Émile Bénard Carlos Obregón Santacilia |

Location of Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City Central | |

History

.jpg)

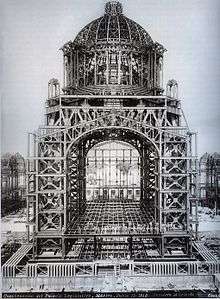

The building was initially planned as the Federal Legislative Palace during the regime of president Porfirio Díaz and "was intended as the unequaled monument to Porfirian glory."[1] The building would hold the congressional chambers of the deputies and senators, but the project was not finished due to the Mexican Revolutionary War. Twenty-five years later, the structure was converted into a monument to the Mexican Revolution by Mexican architect Carlos Obregón Santacilia. The monument is considered the tallest triumphal arch in the world, standing 67 metres (220 ft) in height.[2] Porfirio Díaz appointed a French architect, Émile Bénard to design and construct the palace, a neoclassical design with "characteristic touches of the French renaissance,"[3] showing government officials' aim to demonstrate Mexico's rightful place as an advanced nation. Díaz laid the first stone in 1910 during the centennial celebrations of Independence, when Díaz also inaugurated the Monument to Mexican Independence ("The Angel of Independence").[4] The internal structure was made of iron, and rather than using local Mexican materials in the stone façade, the design called for Italian marble and Norwegian granite.[5]

Although the Díaz regime was ousted in May 1911, President Madero continued the project until his murder in 1913.[6] After Madero's death, the project was cancelled and abandoned for more than twenty years. The structure remained unfinished until 1938, being completed during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas.[7]

The Mexican architect Carlos Obregón Santacilia proposed converting the abandoned structure into a monument to the heroes of the Mexican Revolution. After this was approved, the structure began its eclectic Art Deco and Mexican socialist realism conversion, building over the existing cupola structure of the Palacio Legislativo Federal (Federal Legislative Palace).[8][9] Mexican sculptor Oliverio Martínez designed four stone sculpture groups for the monument,[10] with Francisco Zúñiga as one of his assistants.

The structure also functions as a mausoleum for the heroes of the Mexican Revolution of 1910, Francisco I. Madero, Francisco "Pancho" Villa, Venustiano Carranza, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Lázaro Cárdenas. Revolutionary general Emiliano Zapata is not buried in the monument, but rather in Cuautla, Morelos. The Zapata family has resisted the Mexican government's efforts to relocate Zapata's remains to the monument.[11]

References

- Thomas Benjamin, La Revolución: Mexico's Great Revolution as Memory, Myth, and History. Austin: University of Texas Press 2000, p. 121.

- SkyscraperPage – Monumento a la Revolucion<

- Benjamin, La Revolución, p. 121.

- Benjamin, La Revolución, pp. 121–22.

- Benjamin, La Revolución, p. 122.

- Benjamin, La Revolución, p. 123.

- Jacobo Dale Vuelta, "Está concluido el Monumento a la Revolución," El Universal, 12 Sept 1937.

- Obregón Santacilio, Carlos. El Monumento a la Revolución: Simbolismo e historia. Mexico: Secretaría de Educación Pública 1960.

- Garay Arrelleno, Graciela de. La obra de Carlos Obregón Santacilia, Arquitecto. Mexico: SEP/INBA 1979.

- Benjamin, La Revolución, p. 89, Figure 8 with caption.

- Ilene V. O'Malley, The Myth of the Mexican Revolution: Hero Cults and the Institutionalization of the Mexican State, 1920–1940. New York: Greenwood Press 1986, pp. 69–70.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Monumento a la Revolución (México). |