First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire (Spanish: Imperio Mexicano, pronounced [ĩmˈpeɾjo mexiˈkano] (![]()

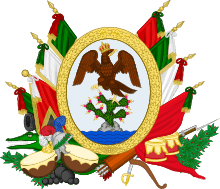

Mexican Empire Imperio Mexicano (in Spanish) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1821–1823 | |||||||||||||||

Motto: Independencia, Unión, Religion "Independence, Union, Religion" | |||||||||||||||

.svg.png) | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Mexico City | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||

• 1822–1823 | Agustín I | ||||||||||||||

| Regent | |||||||||||||||

• 1821–1822 | Agustín de Iturbide | ||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister[1] | |||||||||||||||

• 1822–1823 | José Manuel de Herrera | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Provisional Government Junta (1821–1822) Constituent Congress (1822) National Institutional Junta (1822–1823) | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

| September 28, 1821 | |||||||||||||||

| February 24, 1821 | |||||||||||||||

• Abdication of Agustín I of Mexico | March 19, 1823 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 1821[2] | 4,429,000 km2 (1,710,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1821[3] | 6,500,000 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Mexican real | ||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | MX | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

Agustín de Iturbide, the sole monarch of the empire, was originally the Mexican military commander whose leadership succeeded in gaining independence for the nation from Spain in September 1821. His popularity culminated in mass demonstrations on May 18, 1822 in favor of making him Emperor of the new nation, and the very next day congress hastily approved the matter. A sumptuous coronation ceremony followed in July.

The empire was plagued throughout its short existence by questions about its legality, conflicts between congress and the emperor, and a bankrupt treasury. Iturbide shut down Congress in October 1822, and by December of that year had begun to lose support of the army which revolted in favor of restoring Congress. After failing to put down the revolt, Iturbide reconvened Congress in March, 1823 and offered his abdication, upon which power passed over to a Provisional Government.

Background

Mexico's War of Independence which began in 1810, lasted eleven years and was far from being a homogeneous movement. Its initial purpose, as proclaimed in the Cry of Dolores was to support the return of Ferdinand VII to the throne of Spain after having been overthrown by Napoleon, but later the cause of absolute independence from Spain was adopted by insurgent leaders such as José María Morelos. The Spanish managed to mostly defeat the independence movement, and after Morelos' execution in 1815, the remaining rebels were reduced to waging guerilla warfare in the countryside. Agustín de Iturbide was a Mexican officer in the Spanish army, representative of the Mexican elite who were initially loyal to Spain, but later saw their interests threatened by the liberal 1820 Revolution in Spain. In view of this, Iturbide began to lead a movement to pact with the remaining insurgents and support the separation of Mexico from the Spanish metropole.

The movement involved three principles, or "guarantees,": that Mexico would be an independent constitutional monarchy governed by a Spanish prince; that Americanos, that is all those Mexican-born (regardless of previous racial category), and those Spanish-born would henceforth enjoy equal rights and privileges; and that the Roman Catholic Church would retain its privileges and position as the official and exclusive religion of the land. These Three Guarantees formed the core of the Plan of Iguala, the revolutionary blueprint which, by combining the goal of independence and a constitution with the preservation of Catholic monarchy, brought together all Mexican factions.[4] Under the 24 February 1821 Plan of Iguala, to which most of the provinces subscribed, the Mexican Congress established a regency council which was headed by Iturbide.

Viceroy Juan O'Donojú acceeded to the Mexican demands, and signed the Treaty of Córdoba on August 24, 1821. The Mexican Congress intended to establish a commonwealth, whereby King Fernando VII of Spain would also be Emperor of Mexico, and both countries would be governed by separate laws and form separate legislative bodies. If the king refused the position, the law provided for another member of the House of Bourbon to accede to the Mexican throne.[5] Commissioners from Mexico were sent to Spain to offer the Mexican throne, but the Spanish government refused to recognize Mexico's independence and would not allow any other Spanish prince to accept the throne.

Election

With Ferdinand VII having rejected the Treaty of Cordoba, Iturbide's supporters saw an opportunity to place their candidate on the throne. On the night of May 18th, the 1st infantry regiment, stationed at the ex Convent of San Hipólito, and led by sergeant Pio Marcha began a public demonstration in favor of Iturbide being made emperor. The demonstration was joined by other barracks and many civilians as well. When the public demonstration reached his home, Iturbide himself was able to address the demonstrators from his balcony. He consulted with members of the regency on what course to follow, and eventually aquiesed to the demonstrator's demands, agreeing that he should be made emperor. The crowd celebrated the rest of the night with fireworks and celebratory gunfire.[6]

An extraordinary session of congress was held the following morning to deal with the subject of Iturbide's coronation. At the opening of the session, the military addressed a manifesto to congress, endorsing Iturbide to be emperor. The deliberations then started with a few deputies expressing concern that congress was not entirely free in the present circumstances to proceed on the matter. A pro-Iturbide crowd outside of the hall was making so much noise that it was interfering with the deliberations, and congress asked Iturbide to show up in an unsuccessful attempt to calm the crowds. The opposition brought up concerns that a popular demonstration in the capital was not enough of a basis upon which to elect Iturbide and that the provinces ought to be consulted first. A proposal was made to gain the consent of two thirds of the provinces, and this succeeding then to appoint a commission to write a provisional constitution in order to avoid constitutional crises. [7]

Deputy Valentín Gómez Farías, future president of Mexico, stood up for the legality of congress to elect an emperor. He praised Iturbide's services to the nation, and argued that as Spain had rejected the Treaty of Córdoba, Congress was now authorized by that very treaty to hold an election to decide who the emperor was to be.[8] The vote then proceeded. In the final results, sixty-seven deputies voted in favor of making Iturbide Emperor, while fifteen voted against. The vote however was short of a legal quorum of one hundred and two deputies.[9]

Coronation

Congress, however resigned itself to the situation, and a plan to establish a constitutional monarchy united both conservatives and liberals at a time when it was uncertain which form of government would be best for independent Mexico. [10] Congress published an oath binding the emperor to obey the constitution, which Iturbide subsequently took, and Congress also declared the Mexican monarchy to be hereditary, granting titles of nobility to Iturbide's family. His son and heir became Prince Imperial of Mexico. The 19th of May was made a national holiday, and a royal household was organized. July 21, 1822 was set as the date of the official coronation.[11]

Iturbide's court was being set up to be more luxurious than that of the Viceroy, a situation which provoked some opposition in a new nation that was essentially bankrupt. To remedy the financial difficulties, the Mexican government prohibited the exportation of money, and exacted a forced loan of 600,000 pesos from the private sector in Mexico City, Puebla, Guadalajara, and Veracruz. During this time, a council of state was also formed, being made up of thirteen members selected by the Emperor from a list of thirty one nominees submitted by congress.[12]

The coronation took place on July 21st. The capital was decked out in floral arrangements, banners, streamers, and flags. The government could not afford to forge a crown, and therefore jewels and gems had to be borrowed, but ultimately a signet ring, a scepter and crowns were produced. Costumes were made based on drawings of Napoleon's coronation. Congress met on the morning of the coronation, and then divided itself into two deputations to escort the emperor and the empress to the National Cathedral. In the cathedral, the emperor and the empress were to be seated on thrones next to the newly ennobled Mexican princes and princesses. Upon reaching the cathedral, the emperor and empress were escorted to their thrones, and the imperial regalia was placed on the altar. The regalia was blessed and Iturbide was crowned by the president of the congress.[13]

Reign

| ||

| Cabinet of the Mexican Empire[14] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| Foreign and Interior Relations | José Manuel de Herrera | 19 May 1822 - 10 Aug. 1822 |

| Andrés Quintana Roo | 11 Aug. 1822 - 22 Feb. 1823 | |

| José Cecilio del Valle | 23 Feb. 1823 - 31 Mar. 1823 | |

| Justice and Ecclesiastical Affairs | José Dominguez Manzo | 19 May 1822 - 10 Feb. 1823 |

| Juan Gómez Navarrete | 11 Feb. 1823 - 29 Mar. 1823 | |

| Treasury | Rafael Pérez Maldonado | 19 May 1822 - 30 Jun. 1822 |

| Antonio de Medina | 1 Jul. 1822 - 31 Mar. 1823 | |

| War and Marine | Antonio de Medina | 19 May. 1822 - 30 Jun. 1822 |

| Manuel de la Sota Riva | 1 Jul. 1822 - 23 Mar. 1823 | |

| Francisco de Arrillaga | 24 Mar. 1823 - 31 Mar. 1823 | |

Congress and the Emperor immediately began to clash, one of the first points of controversy being over the right of appointing members to a supreme court. All the while, work on a constitution for the Empire was being neglected.[15] Iturbide's greatest enemy in congress was deputy Servando Teresa de Mier, a staunch republican, who would often ridicule the Emperor and his pageantry.[16]

In August, 1822 a conspiracy to overthrow the Emperor was discovered. The conspirators, claiming that Iturbide's election was illegal, plotted to rise up in the capital, move the congress to Texcoco and declare the establishment of a Republic. On the 26th and 27th of August, fifteen deputies suspected of being involved with the plot were arrested, including Mier. Congress was shocked by the arrests, which had included some of its most prominent deputies, and on the morning of August 27, the legislature sent a letter to the military upholding the immunity of congress, and accusing the arresting authorities of acting in an extra-legal fashion. Secretary of Interior Relations, Andrés Quintana Roo replied that by virtue of the Spanish Constitution of 1812, the government had the authority to arrest deputies suspected of being involved in a treasonous conspiracy, and that congress would remain informed on the results of the ongoing investigation. Congress preferred to try the suspected deputies itself, but the matter was rejected. The prosecution against the accused did not get very far and a few were liberated around Christmas, 1822.[17] [18]

Afterwards followed controversies over reconstituting Congress. On October 17th, 1822, Iturbide with his council of state and several sympathetic deputies, produced a proposal to reduce the number of deputies to seventy. Congress rejected the measure, but a compromise was reached by which the legislature agreed to abide by the Spanish Constitution of 1812 as a provisional constitution, allowing Iturbide a veto over legislation, and the right to select members of the supreme court. Iturbide however then sought for more concessions, arguing that his veto ought to extend to any article of any new constitution that congress would draft, and also continued to insist on reducing the number of deputies in congress. These grabs for power alienated even conservatives, and Iturbide's proposals were rejected, which Iturbide then responded to by dissolving congress using the military on October 31, 1822.[19] [20]

To replace congress, Iturbide established a junta of forty five members, chosen from among friendly deputies. The junta was installed officially on November 2, 1822, and vested with the legislative power, until a new congress could be formed. Iturbide entrusted the body with writing up regulations for producing a new congress, but also began to focus on the grave financial issues that the Empire was facing. On November 5, 1822, the junta authorized a forced loan of over two million pesos, and the seizure of more than one million pesos waiting for exportation out of the country in the port of Veracruz.[21]

Iturbide also began to issue paper currency, and on December 20th, the government authorized the printing of four million pesos worth of banknotes, in denominations of one, two, and ten. These were issued to all financial offices of the Empire, where they were to be used in a ratio of 1:2 with silver coin in payment of all government of obligations. Anyone who owed money to the government was allowed to make one third of the payment in notes and two thirds in coin. [22]

Revolt Against the Emperor

The last Spanish stronghold in Mexico, was Fort of San Juan de Ullua on a small island off the coast of Veracruz. There had been a change in command at the fort during this time, and general Santa Anna, stationed in Veracruz planned a scheme of taking possession of it by feigning the surrender of Veracruz to its new commander. When Echevarri, the captain-general of the local provinces, arrived in Veracruz, he approved of the plan, and agreed to join in on it, positioning his troops in Veracruz to ambush the landing Spaniards, having been promised support by Santa Anna. On October 26th, 1822 as the Spaniards landed however, Santa Anna's troops failed to arrive, and Echevarri barely defeated the landing party, and the Spanish ultimately kept control of the fort. Echevarri expressed his suspicion to Iturbide that it had all been a scheme by Santa Anna to get Echeverri killed as revenge for Santa Anna not having been appointed Captain-General himself. Iturbide himself went to Veracruz to dismiss Santa Anna from his command, not overtly however but rather under the pretext of simply moving him to a different post in Mexico City. However, Santa Anna suspecting his ruin, instead took command of his troops and in December, 1822 started a rebellion in favor of a republican form of government. [23]

Vicente Guerrero and Nicolas Bravo, defected from the ranks of the imperialists, and proceeded to Chilapa on January 5th, 1823 to join the revolution, but experienced a disastrous defeat at Almolonga. The insurrection was mostly being suppresed at this time, Victoria being held in check at Puente del Rey, and Santa Anna still confined at Veracruz. [24]

At this point however, opposition to the government began to negotiate with the military. Echevarri was sent to take care of the rebellion in Veracruz, but ended up defecting. On February 1st, 1823 a junta of military chiefs met to proclaim the Plan of Casa Mata. The army pledged itself to restore Congress while disavowing any intention of harming the person of the Emperor, or of overthrowing the Mexican monarchy. On February 14th, Puebla proclaimed for the plan, followed by San Luis Potosi, and Guadalajara. By March, most of Mexico had proclaimed in favor of the plan. [25] A military junta was formed in Jalapa, to represent the Plan of Casa Mata.

Iturbide's Abdication

On March 4th, 1823, Iturbide issued a decree reconvening Congress, and the deputies met on March 7th. Iturbide addressed the session, hoping to reach a negotiation and avoid conflict, but the deputies listened coldly. The military junta refused to recognize the Congress until its liberty was guaranteed. On March 19th, Iturbide fearing his imminent overthrowal, summoned congress to an extraordinary session and presented his abdication. Congress proposed that the military junta meet with Iturbide about the matter, but the junta refused, instead proposing that Iturbide remove himself from the capital, and await the decision of Congress. On March 26th, an agreement was reached by which the Junta would recognized Iturbide on whatever terms Congress would grant him. Iturbide also agreed to remove himself from the capital, and the command of the capital was handed over to the revolutionary troops and power passed over to the Provisional Government of Mexico. [26]

Territory

.svg.png)

The territory of the Mexican Empire corresponded to the borders of Viceroyalty of New Spain, excluding the Captaincies General of Cuba, Santo Domingo and the Philippines. The Central American lands of the former Captaincy General of Guatemala were annexed to the Empire shortly after its establishment.

Under the First Empire, Mexico reached its greatest territorial extent, stretching from northern California to the provinces of Central America (excluding Panama, which was then part of Colombia), which had not initially approved becoming part of the Mexican Empire but joined the Empire shortly after their independence.[27]

After the emperor abdicated, on March 29 the departing Mexican general Vicente Filisola called for a new Central American Congress to convene and on July 1, 1823 the Central American provinces formed the Federal Republic of Central America, with only the province of Chiapas choosing to remain a part of Mexico as a state. Subsequent territorial evolution of Mexico over the next several decades (principally cessions to the United States) would eventually reduce Mexico to less than half its maximum extent.

Political subdivisions

The first Mexican empire was divided into the following intendances:

- Las Californias

- México

- Nuevo México

- Texas

- Nueva Vizcaya

- Coahuila

- Nuevo Reino de León

- Nuevo Santander

- Estado de Occidente

- Zacatecas

- San Luis de Potosí

- Guanajuato

- Querétaro

- Puebla

- Guadalajara

- Oaxaca

- Mérida de Yucatán

- Valladolid

- Veracruz

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- El Salvador

- Nicaragua

- Costa Rica

See also

- Federal Republic of Central America

- History of Mexico

- Imperial Crown of Mexico

- List of Emperors of Mexico

- Mexican Imperial Orders

- Second Mexican Empire

References

- Porvenir De México y Juicio Sobre Su Estado Político En 1821 Y 1851, Volumen1 Por Luis Gonzaga Cuevas

- Rodriguez, Jaime E.; Vincent, Kathryn (1997). Myths, Misdeeds, and Misunderstandings: The Roots of Conflict in U.S.-Mexican Relations. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8420-2662-8.

- "The population in Mexico". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Michael S. Werner, ed. (2001). Concise Encyclopedia of Mexico. Taylor & Francis. pp. 308–9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- The Birth of Modern Mexico, 1780–1824

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. pp. 770–771.

- Zamacois, Niceto (1879). Historia de Méjico: Tomo 11 (in Spanish). Mexico City: J.F. Barres and Co. pp. 290–296.

- Zamacois, Niceto (1879). Historia de Méjico: Tomo 11 (in Spanish). Mexico City: J.F. Barres and Co. p. 297.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. pp. 770–771.

- Shawcross, Edward (2018). France, Mexico and Informal Empire in Latin America. Springer International. p. 85.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. pp. 774–775.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. p. 776.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. pp. 777–778.

- Memoria de hacienda y credito publico. Mexico City: Mexican Government. 1870. p. 1026.

- Zamacois, Niceto (1879). Historia de Méjico: Tomo 11 (in Spanish). Mexico City: J.F. Barres and Co. p. 358.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. pp. 780–781.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. pp. 782–783.

- Zamacois, Niceto (1879). Historia de Méjico: Tomo 11 (in Spanish). Mexico City: J.F. Barres and Co. pp. 372–373.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. p. 784.

- Christon I. Archer (2007). The Birth of Modern Mexico, 1780–1824. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 220.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. p. 785.

- Payno, Manuel (1862). Mexico and Her Financial Questions. Mexico: Ignacio Cumplido. p. 31.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. pp. 786–789.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. pp. 792–793.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. pp. 793–794.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1862). History of Mexico Vol. 4. New York: The Bancroft Company. pp. 801–802.

- Quirarte, Martín (1978). Visión Panorámica de la Historia de México (11th ed.). Mexico: Librería Porrúa Hnos.

Further reading

- Anna, Timothy. The Mexican Empire of Iturbide. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1990.

- Benson, Nettie Lee. "The Plan of Casa Mata" Hispanic American Historical Review. 25 (February 1945) pp. 45–56.

- Weber, David J. “The Spanish Borderlands, Historiography Redux.” The History Teacher, 39#1 (2005), pp. 43–56. , online.

In Spanish

- Arcila Farias, Eduardo. El siglo ilustrado en América. Reformas económicas del siglo XVIII en Nueva España. México, D. F., 1974.

- Calderón Quijano, José Antonio. Los Virreyes de Nueva España durante el reinado de Carlos III. Sevilla, 1967–1968.

- Céspedes del Castillo, Guillermo. América Hispánica (1492-1898). Barcelona: Labor, 1985.

- Hernández Sánchez-Barba, Mario. Historia de América. Madrid: Alhambra, 1981.

- Konetzke, Richard. América Latina. La época colonial. Madrid: Siglo XXI de España, 1976.

- Navarro García, Luis. Hispanoamérica en el siglo XVIII. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, 1975.

- Pérez-Mallaína, Pablo Emilio et al. Historia Moderna. Madrid: Cátedra, 1992.

- Ramos Pérez, Demetrio et al. América en el siglo XVII. Madrid: Rialp, 1982–1989.

- Ramos Pérez, Demetrio et al. América en el siglo XVIII. Madrid: Rialp, 1982–1989.

- Richmond, Douglas W. "Agustín de Iturbide" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 711–713.

- Robertson, William Spence. Iturbide of Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press 1952.

- Rubio Mañé, Ignacio. Introducción al estudio de los virreyes de Nueva España, 1535–1746. Mexico City, 2nd ed., 1983.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Mexican Empire. |