The Bahamas

The Bahamas (/bəˈhɑːməz/ (![]()

Commonwealth of The Bahamas | |

|---|---|

Flag

Coat of arms

| |

Motto: "Forward, Upward, Onward, Together" | |

.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city | Nassau 25°4′N 77°20′W |

| Official languages | English |

| Vernacular language | Bahamian English |

| Ethnic groups (2010) | 90.6% Afro-Bahamian 4.7% European 2.1% Mulatto 1.9% Other 0.7% Unspecified[1][2] |

| Religion (2010)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Bahamian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy[4][5] |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Sir Cornelius A. Smith | |

| Hubert Minnis | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Assembly | |

| Independence | |

• from the United Kingdom | 10 July 1973[6] |

| Area | |

• Total | 13,878 km2 (5,358 sq mi) (155th) |

• Water (%) | 28% |

| Population | |

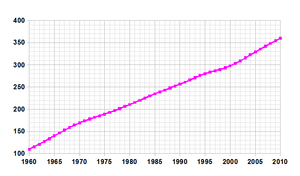

• 2018 estimate | 385,637[7][8] (177th) |

• 2010 census | 351,461 |

• Density | 25.21/km2 (65.3/sq mi) (181st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $12.612 billion[9] (148th) |

• Per capita | $33,494[9] (40th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $12.803 billion[9] (130th) |

• Per capita | $34,002[9] (26th) |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 60th |

| Currency | Bahamian dollar (BSD) (US dollars widely accepted) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| UTC−4 (EDT) | |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +1 242 |

| ISO 3166 code | BS |

| Internet TLD | .bs |

The Bahamas were inhabited by the Lucayans, a branch of the Arawakan-speaking Taíno people, for many centuries.[13] Columbus was the first European to see the islands, making his first landfall in the 'New World' in 1492. Later, the Spanish shipped the native Lucayans to slavery on Hispaniola, after which the Bahama islands were mostly deserted from 1513 until 1648, when English colonists from Bermuda settled on the island of Eleuthera.

The Bahamas became a British crown colony in 1718, when the British clamped down on piracy. After the American Revolutionary War, the Crown resettled thousands of American Loyalists to The Bahamas; they took their slaves with them and established plantations on land grants. African slaves and their descendants constituted the majority of the population from this period on. The slave trade was abolished by the British in 1807; slavery in The Bahamas was abolished in 1834. Subsequently, The Bahamas became a haven for freed African slaves. Africans liberated from illegal slave ships were resettled on the islands by the Royal Navy, while some North American slaves and Seminoles escaped to The Bahamas from Florida. Bahamians were even known to recognise the freedom of slaves carried by the ships of other nations which reached The Bahamas. Today Afro-Bahamians make up 90% of the population of 332,634.[13]

The country gained governmental independence in 1973 led by Sir Lynden O. Pindling, with Elizabeth II as its queen.[13] In terms of gross domestic product per capita, The Bahamas is one of the richest countries in the Americas (following the United States and Canada), with an economy based on tourism and offshore finance.[14]

Etymology

The name Bahamas is most likely derived from either the Taíno ba ha ma ("big upper middle land"), which was a term for the region used by the indigenous people,[15] or possibly from the Spanish baja mar ("shallow water or sea" or "low tide") reflecting the shallow waters of the area. Alternatively, it may originate from Guanahani, a local name of unclear meaning.

The word The constitutes an integral part of the short form of the name and is, therefore, capitalised. The Constitution of the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, the country's fundamental law, capitalises the "T" in "The Bahamas".[16]

History

Pre-colonial era

The first inhabitants of The Bahamas were the Taino people, who moved into the uninhabited southern islands from Hispaniola and Cuba around the 800s–1000s AD, having migrated there from South America; they came to be known as the Lucayan people.[17] An estimated 30,000 Lucayans inhabited The Bahamas at the time of Christopher Columbus's arrival in 1492.[18]

Arrival of the Spanish

Columbus's first landfall in what was to Europeans a 'New World' was on an island he named San Salvador (known to the Lucayans as Guanahani). Whilst there is a general consensus that this island lay within The Bahamas, precisely which island Columbus landed on is a matter of scholarly debate. Some researchers believe the site to be present-day San Salvador Island (formerly known as Watling's Island), situated in the southeastern Bahamas, whilst an alternative theory holds that Columbus landed to the southeast on Samana Cay, according to calculations made in 1986 by National Geographic writer and editor Joseph Judge, based on Columbus's log. On the landfall island, Columbus made first contact with the Lucayans and exchanged goods with them, claiming the islands for the Crown of Castile, before proceeding to explore the larger isles of the Greater Antilles.[17]

The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas theoretically divided the new territories between the Kingdom of Castile and the Kingdom of Portugal, placing The Bahamas in the Spanish sphere; however they did little to press their claim on the ground. The Spanish did however make use of the native Lucayan peoples, many of whom were enslaved and sent to Hispaniola for use as forced labour.[17] The slaves suffered from harsh conditions and most died from contracting diseases to which they had no immunity; half of the Taino died from smallpox alone.[20] As a result of these depredations the population of The Bahamas was severely diminished.[21]

Arrival of the English

The English had expressed an interest in The Bahamas as early as 1629. However, it was not until 1648 that the first English settlers arrived on the islands. Known as the Eleutherian Adventurers and led by William Sayle, they migrated to Bermuda seeking greater religious freedom. These English Puritans established the first permanent European settlement on an island which they named 'Eleuthera', Greek for 'freedom'. They later settled New Providence, naming it Sayle's Island. Life proved harder than envisaged however, and many – including Sayle – chose to return to Bermuda.[17] To survive, the remaining settlers salvaged goods from wrecks.

In 1670, King Charles II granted the islands to the Lords Proprietors of the Carolinas in North America. They rented the islands from the king with rights of trading, tax, appointing governors, and administering the country from their base on New Providence.[22][17] Piracy and attacks from hostile foreign powers were a constant threat. In 1684, Spanish corsair Juan de Alcon raided the capital Charles Town (later renamed Nassau),[23] and in 1703, a joint Franco-Spanish expedition briefly occupied Nassau during the War of the Spanish Succession.[24][25]

18th century

During proprietary rule, The Bahamas became a haven for pirates, including Blackbeard (circa 1680–1718).[26] To put an end to the 'Pirates' republic' and restore orderly government, Great Britain made The Bahamas a crown colony in 1718 under the royal governorship of Woodes Rogers.[17] After a difficult struggle, he succeeded in suppressing piracy.[27] In 1720, the Spanish attacked Nassau during the War of the Quadruple Alliance. In 1729, a local assembly was established giving a degree of self-governance for the English settlers.[17][28] The reforms had been planned by the previous Governor George Phenney and authorised in July 1728.[29]

During the American War of Independence in the late 18th century, the islands became a target for US naval forces. Under the command of Commodore Esek Hopkins; US Marines, the US Navy occupied Nassau in 1776, before being evacuated a few days later. In 1782 a Spanish fleet appeared off the coast of Nassau, and the city surrendered without a fight. Spain returned possession of The Bahamas to Great Britain the following year, under the terms of the Treaty of Paris. Before the news was received however, the islands were recaptured by a small British force led by Andrew Deveaux.[17]

After US independence, the British resettled some 7,300 Loyalists with their African slaves in The Bahamas, including 2,000 from New York[30] and at least 1,033 whites, 2,214 blacks and a few Native American Creeks from East Florida. Most of the refugees resettled from New York had fled from other colonies, including West Florida, which the Spanish captured during the war.[31] The government granted land to the planters to help compensate for losses on the continent. These Loyalists, who included Deveaux and also Lord Dunmore, established plantations on several islands and became a political force in the capital.[17] European Americans were outnumbered by the African-American slaves they brought with them, and ethnic Europeans remained a minority in the territory.

19th century

In 1807, the British abolished the slave trade.[17] During the following decades, the Royal Navy intercepted the trade. They resettled in The Bahamas thousands of Africans liberated from slave ships.

In the 1820s during the period of the Seminole Wars in Florida, hundreds of North American slaves and African Seminoles escaped from Cape Florida to The Bahamas. They settled mostly on northwest Andros Island, where they developed the village of Red Bays. From eyewitness accounts, 300 escaped in a mass flight in 1823, aided by Bahamians in 27 sloops, with others using canoes for the journey. This was commemorated in 2004 by a large sign at Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park.[32][33] Some of their descendants in Red Bays continue African Seminole traditions in basket making and grave marking.[34]

In 1818,[35] the Home Office in London had ruled that "any slave brought to The Bahamas from outside the British West Indies would be manumitted." This led to a total of nearly 300 slaves owned by US nationals being freed from 1830 to 1835.[36] The American slave ships Comet and Encomium used in the United States domestic coastwise slave trade, were wrecked off Abaco Island in December 1830 and February 1834, respectively. When wreckers took the masters, passengers and slaves into Nassau, customs officers seized the slaves and British colonial officials freed them, over the protests of the Americans. There were 165 slaves on the Comet and 48 on the Encomium. The United Kingdom finally paid an indemnity to the United States in those two cases in 1855, under the Treaty of Claims of 1853, which settled several compensation cases between the two countries.[37][38]

Slavery was abolished in the British Empire on 1 August 1834.[17] After that British colonial officials freed 78 North American slaves from the Enterprise, which went into Bermuda in 1835; and 38 from the Hermosa, which wrecked off Abaco Island in 1840.[39] The most notable case was that of the Creole in 1841: as a result of a slave revolt on board, the leaders ordered the US brig to Nassau. It was carrying 135 slaves from Virginia destined for sale in New Orleans. The Bahamian officials freed the 128 slaves who chose to stay in the islands. The Creole case has been described as the "most successful slave revolt in U.S. history".[40]

These incidents, in which a total of 447 slaves belonging to US nationals were freed from 1830 to 1842, increased tension between the United States and the United Kingdom. They had been co-operating in patrols to suppress the international slave trade. However, worried about the stability of its large domestic slave trade and its value, the United States argued that the United Kingdom should not treat its domestic ships that came to its colonial ports under duress as part of the international trade. The United States worried that the success of the Creole slaves in gaining freedom would encourage more slave revolts on merchant ships.

During the American Civil War of the 1860s, the islands briefly prospered as a focus for blockade runners aiding the Confederate States.[41][42]

Early 20th century

The early decades of the 20th century were ones of hardship for many Bahamians, characterised by a stagnant economy and widespread poverty. Many eked out a living via subsistence agriculture or fishing.[17]

.jpg)

In August 1940, the Duke of Windsor was appointed Governor of The Bahamas. He arrived in the colony with his wife. Although disheartened at the condition of Government House, they "tried to make the best of a bad situation".[43] He did not enjoy the position, and referred to the islands as "a third-class British colony".[44] He opened the small local parliament on 29 October 1940. The couple visited the "Out Islands" that November, on Axel Wenner-Gren's yacht, which caused controversy;[45] the British Foreign Office strenuously objected because they had been advised by United States intelligence that Wenner-Gren was a close friend of the Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring of Nazi Germany.[45][46]

The Duke was praised at the time for his efforts to combat poverty on the islands. A 1991 biography by Philip Ziegler, however, described him as contemptuous of the Bahamians and other non-European peoples of the Empire. He was praised for his resolution of civil unrest over low wages in Nassau in June 1942, when there was a "full-scale riot".[47] Ziegler said that the Duke blamed the trouble on "mischief makers – communists" and "men of Central European Jewish descent, who had secured jobs as a pretext for obtaining a deferment of draft".[48] The Duke resigned from the post on 16 March 1945.[49][50]

Post-Second World War

.svg.png)

Modern political development began after the Second World War. The first political parties were formed in the 1950s, split broadly along ethnic lines – the United Bahamian Party (UBP) representing the English-descended Bahamians (known informally as the 'Bay Street Boys'),[51] and the Progressive Liberal Party (PLP) representing the Afro-Bahamian majority.[17]

A new constitution granting The Bahamas internal autonomy went into effect on 7 January 1964, with Chief Minister Sir Roland Symonette of the UBP becoming the first Premier.[52]:p.73[53] In 1967, Lynden Pindling of the PLP became the first black Premier of the Bahamian colony; in 1968, the title of the position was changed to Prime Minister. In 1968, Pindling announced that The Bahamas would seek full independence.[54] A new constitution giving The Bahamas increased control over its own affairs was adopted in 1968.[55] In 1971, the UBP merged with a disaffected faction of the PLP to form a new party, the Free National Movement (FNM), a de-racialised, centre-right party which aimed to counter the growing power of Pindling's PLP.[56]

The British House of Lords voted to give The Bahamas its independence on 22 June 1973.[57] Prince Charles delivered the official documents to Prime Minister Lynden Pindling, officially declaring The Bahamas a fully independent nation on 10 July 1973,[58] and this date is now celebrated as the country's Independence Day.[59] It joined the Commonwealth of Nations on the same day.[60] Sir Milo Butler was appointed the first governor-general of The Bahamas (the official representative of Queen Elizabeth II) shortly after independence.[61]

Post-independence

Shortly after independence, The Bahamas joined the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank on 22 August 1973,[62] and later the United Nations on 18 September 1973.[63]

Politically, the first two decades were dominated by Pindling's PLP, who went on to win a string of electoral victories. Allegations of corruption, links with drug cartels and financial malfeasance within the Bahamian government failed to dent Pindling's popularity. Meanwhile, the economy underwent a dramatic growth period fueled by the twin pillars of tourism and offshore finance, significantly raising the standard of living on the islands. The Bahamas' booming economy led to it becoming a beacon for immigrants, most notably from Haiti.[17]

In 1992, Pindling was unseated by Hubert Ingraham of the FNM.[52]:p.78 Ingraham went on to win the 1997 Bahamian general election, before being defeated in 2002, when the PLP returned to power under Perry Christie.[52]:p.82 Ingraham returned to power from 2007–2012, followed by Christie again from 2012–17. With economic growth faltering, Bahamians re-elected the FNM in 2017, with Hubert Minnis becoming the fourth prime minister.[17]

In September 2019, Hurricane Dorian struck the Abaco Islands and Grand Bahama at Category 5 intensity, devastating the northwestern Bahamas. The storm inflicted at least US$7 billion in damages and killed more than 50 people,[64][65] with 1,300 people still missing.[66]

Geography

.png)

The Bahamas consists of a chain of islands spread out over some 800 kilometres (500 mi) in the Atlantic Ocean, located to the east of Florida in the United States, north of Cuba and Hispaniola and west of the British Overseas Territory of the Turks and Caicos Islands (with which it forms the Lucayan archipelago). It lies between latitudes 20° and 28°N, and longitudes 72° and 80°W and straddles the Tropic of Cancer.[13] There are some 700 islands and cays in total (of which 30 are inhabited) with a total land area of 10,010 km2 (3,860 sq mi).[13][17]

Nassau, capital city of The Bahamas, lies on the island of New Providence; the other main inhabited islands are Grand Bahama, Eleuthera, Cat Island, Rum Cay, Long Island, San Salvador Island, Ragged Island, Acklins, Crooked Island, Exuma, Berry Islands, Mayaguana, the Bimini islands, Great Abaco and Great Inagua. The largest island is Andros.[17]

All the islands are low and flat, with ridges that usually rise no more than 15 to 20 m (49 to 66 ft). The highest point in the country is Mount Alvernia (formerly Como Hill) on Cat Island at 64 m (210 ft).[13]

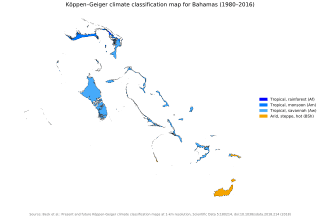

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification, the climate of The Bahamas is mostly tropical savannah climate or Aw, with a hot and wet season and a warm and dry season. The low latitude, warm tropical Gulf Stream, and low elevation give The Bahamas a warm and winterless climate.[67]

As with most tropical climates, seasonal rainfall follows the sun, and summer is the wettest season. There is only a 7 °C (13 °F) difference between the warmest month and coolest month in most of the Bahama islands. Every few decades low temperatures can fall below 10 °C (50 °F) for a few hours when a severe cold outbreak comes down from the North American mainland, however there has never been a frost or freeze recorded in the Bahamian Islands. Only once in recorded history has snow been seen in the air anywhere in The Bahamas, this occurred in Freeport on 19 January 1977, when snow mixed with rain was seen in the air for a short time.[68] The Bahamas are often sunny and dry for long periods of time, and average more than 3,000 hours or 340 days of sunlight annually. Much of the natural vegetation is tropical scrub and cactus and succulents are common in landscapes.[69]

Tropical storms and hurricanes occasionally impact The Bahamas. In 1992, Hurricane Andrew passed over the northern portions of the islands, and Hurricane Floyd passed near the eastern portions of the islands in 1999. Hurricane Dorian of 2019 passed over the archipelago at destructive Category 5 strength with sustained winds of 298 km/h (185 mph) and wind gusts up to 350 km/h (220 mph), becoming the strongest tropical cyclone on record to impact the northwestern islands of Grand Bahama and Great Abaco.[70]

| Climate data for Nassau | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.4 (77.7) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

29.7 (85.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.6 (88.9) |

29.9 (85.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.8 (83.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

24.2 (75.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.8 (76.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 17.3 (63.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.8 (69.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39.4 (1.55) |

49.5 (1.95) |

54.4 (2.14) |

69.3 (2.73) |

105.9 (4.17) |

218.2 (8.59) |

160.8 (6.33) |

235.7 (9.28) |

164.1 (6.46) |

161.8 (6.37) |

80.5 (3.17) |

49.8 (1.96) |

1,389.4 (54.70) |

| Average precipitation days | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 140 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 220.1 | 220.4 | 257.3 | 276.0 | 269.7 | 231.0 | 272.8 | 266.6 | 213.0 | 223.2 | 222.0 | 213.9 | 2,886 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN),[71] Hong Kong Observatory (sun only)[72] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 °C (73 °F) |

24 °C (75 °F) |

24 °C (75 °F) |

26 °C (79 °F) |

27 °C (81 °F) |

28 °C (82 °F) |

28 °C (82 °F) |

28 °C (82 °F) |

28 °C (82 °F) |

27 °C (81 °F) |

26 °C (79 °F) |

24 °C (75 °F) |

Geology

The Bahamas is part of the Lucayan Archipelago, which continues into the Turks and Caicos Islands, the Mouchoir Bank, the Silver Bank, and the Navidad Bank.[73]

The Bahamas Platform, which includes The Bahamas, Southern Florida, Northern Cuba, the Turks and Caicos, and the Blake Plateau, formed about 150 Ma, not long after the formation of the North Atlantic. The 6.4 km (4.0 mi) thick limestones, which predominate in The Bahamas, date back to the Cretaceous. These limestones would have been deposited in shallow seas, assumed to be a stretched and thinned portion of the North American continental crust. Sediments were forming at about the same rate as the crust below was sinking due to the added weight. Thus, the entire area consisted of a large marine plain with some islands. Then, at about 80 Ma, the area became flooded by the Gulf Stream. This resulted in the drowning of the Blake Plateau, the separation of The Bahamas from Cuba and Florida, the separation of the southeastern Bahamas into separate banks, the creation of the Cay Sal Bank, plus the Little and Great Bahama Banks. Sedimentation from the "carbonate factory" of each bank, or atoll, continues today at the rate of about 20 mm (0.79 in) per kyr. Coral reefs form the "retaining walls" of these atolls, within which oolites and pellets form.[74]

Coral growth was greater through the Tertiary, until the start of the ice ages, and hence those deposits are more abundant below a depth of 36 m (118 ft). In fact, an ancient extinct reef exists half a km seaward of the present one, 30 m (98 ft) below sea level. Oolites form when oceanic water penetrate the shallow banks, increasing the temperature about 3 °C (5.4 °F) and the salinity by 0.5 per cent. Cemented ooids are referred to as grapestone. Additionally, giant stromatolites are found off the Exuma Cays.[74]:22,29–30

Sea level changes resulted in a drop in sea level, causing wind blown oolite to form sand dunes with distinct cross-bedding. Overlapping dunes form oolitic ridges, which become rapidly lithified through the action of rainwater, called eolianite. Most islands have ridges ranging from 30 to 45 m (98 to 148 ft), though Cat Island has a ridge 60 m (200 ft) in height. The land between ridges is conducive to the formation of lakes and swamps.[74]:41–59,61–64

Solution weathering of the limestone results in a "Bahamian Karst" topography. This includes potholes, blue holes such as Dean's Blue Hole, sinkholes, beachrock such as the Bimini Road ("pavements of Atlantis"), limestone crust, caves due to the lack of rivers, and sea caves. Several blue holes are aligned along the South Andros Fault line. Tidal flats and tidal creeks are common, but the more impressive drainage patterns are formed by troughs and canyons such as Great Bahama Canyon with the evidence of turbidity currents and turbidite deposition.[74]:33–40,65,72–84,86

The stratigraphy of the islands consists of the Middle Pleistocene Owl's Hole Formation, overlain by the Late Pleistocene Grotto Beach Formation, and then the Holocene Rice Bay Formation. However, these units are not necessarily stacked on top of each other but can be located laterally. The oldest formation, Owl's Hole, is capped by a terra rosa paleosoil, as is the Grotto Beach, unless eroded. The Grotto Beach Formation is the most widespread.[73]

Government and politics

The Bahamas is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy, with the queen of the Bahamas (Elizabeth II) as head of state represented locally by a governor-general.[13] Political and legal traditions closely follow those of the United Kingdom and the Westminster system.[17] The Bahamas is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations and shares its head of state with other Commonwealth realms.

The prime minister is the head of government and is the leader of the party with the most seats in the House of Assembly.[13][17] Executive power is exercised by the Cabinet, selected by the prime minister and drawn from his supporters in the House of Assembly. The current governor-general is The Honourable Cornelius A. Smith, and the current prime minister is The Rt. Hon. Hubert Minnis MP.[13]

Legislative power is vested In a bicameral parliament, which consists of a 38-member House of Assembly (the lower house), with members elected from single-member districts, and a 16-member Senate, with members appointed by the governor-general, including nine on the advice of the Prime Minister, four on the advice of the leader of Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition, and three on the advice of the prime minister after consultation with the Leader of the Opposition. As under the Westminster system, the prime minister may dissolve Parliament and call a general election at any time within a five-year term.[75]

Constitutional safeguards include freedom of speech, press, worship, movement and association. The Judiciary of the Bahamas is independent of the executive and the legislature. Jurisprudence is based on English law.[13]

Political culture

.jpg)

The Bahamas has a two-party system dominated by the centre-left Progressive Liberal Party and the centre-right Free National Movement. A handful of other political parties have been unable to win election to parliament; these have included the Bahamas Democratic Movement, the Coalition for Democratic Reform, Bahamian Nationalist Party and the Democratic National Alliance.

Foreign relations

The Bahamas has strong bilateral relationships with the United States and the United Kingdom, represented by an ambassador in Washington and High Commissioner in London. The Bahamas also associates closely with other nations of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM).

Armed forces

The Bahamanian military is the Royal Bahamas Defence Force (RBDF),[13] the navy of The Bahamas which includes a land unit called Commando Squadron (Regiment) and an Air Wing (Air Force). Under the Defence Act, the RBDF has been mandated, in the name of the queen, to defend The Bahamas, protect its territorial integrity, patrol its waters, provide assistance and relief in times of disaster, maintain order in conjunction with the law enforcement agencies of The Bahamas, and carry out any such duties as determined by the National Security Council. The Defence Force is also a member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM)'s Regional Security Task Force.

The RBDF came into existence on 31 March 1980. Its duties include defending The Bahamas, stopping drug smuggling, illegal immigration and poaching, and providing assistance to mariners. The Defence Force has a fleet of 26 coastal and inshore patrol craft along with 3 aircraft and over 1,100 personnel including 65 officers and 74 women.

Administrative divisions

.png)

The districts of The Bahamas provide a system of local government everywhere except New Providence (which holds 70 percent of the national population), whose affairs are handled directly by the central government. In 1996, the Bahamian Parliament passed the "Local Government Act" to facilitate the establishment of family island administrators, local government districts, local district councillors and local town committees for the various island communities. The overall goal of this act is to allow the various elected leaders to govern and oversee the affairs of their respective districts without the interference of the central government. In total, there are 32 districts, with elections being held every five years. There are 110 councillors and 281 town committee members elected to represent the various districts.[76]

Each councillor or town committee member is responsible for the proper use of public funds for the maintenance and development of their constituency.

The districts other than New Providence are:

- Acklins

- Berry Islands

- Bimini

- Black Point, Exuma

- Cat Island

- Central Abaco

- Central Andros

- Central Eleuthera

- City of Freeport, Grand Bahama

- Crooked Island

- East Grand Bahama

- Exuma

- Grand Cay, Abaco

- Harbour Island, Eleuthera

- Hope Town, Abaco

- Inagua

- Long Island

- Mangrove Cay, Andros

- Mayaguana

- Moore's Island, Abaco

- North Abaco

- North Andros

- North Eleuthera

- Ragged Island

- Rum Cay

- San Salvador

- South Abaco

- South Andros

- South Eleuthera

- Spanish Wells, Eleuthera

- West Grand Bahama

National flag

The Bahamian flag was adopted in 1973. Its colours symbolise the strength of the Bahamian people; its design reflects aspects of the natural environment (sun and sea) and economic and social development.[13] The flag is a black equilateral triangle against the mast, superimposed on a horizontal background made up of three equal stripes of aquamarine, gold and aquamarine.[13]

Coat of arms

The coat of arms of The Bahamas contains a shield with the national symbols as its focal point. The shield is supported by a marlin and a flamingo, which are the national animals of The Bahamas. The flamingo is located on the land, and the marlin on the sea, indicating the geography of the islands.

On top of the shield is a conch shell, which represents the varied marine life of the island chain. The conch shell rests on a helmet. Below this is the actual shield, the main symbol of which is a ship representing the Santa María of Christopher Columbus, shown sailing beneath the sun. Along the bottom, below the shield appears a banner upon which is the national motto:[77]

"Forward, Upward, Onward Together."

National flower

The yellow elder was chosen as the national flower of The Bahamas because it is native to the Bahama islands, and it blooms throughout the year.

Selection of the yellow elder over many other flowers was made through the combined popular vote of members of all four of New Providence's garden clubs of the 1970s—the Nassau Garden Club, the Carver Garden Club, the International Garden Club and the YWCA Garden Club. They reasoned that other flowers grown there—such as the bougainvillea, hibiscus and poinciana—had already been chosen as the national flowers of other countries. The yellow elder, on the other hand, was unclaimed by other countries (although it is now also the national flower of the United States Virgin Islands) and also the yellow elder is native to the family islands.[78]

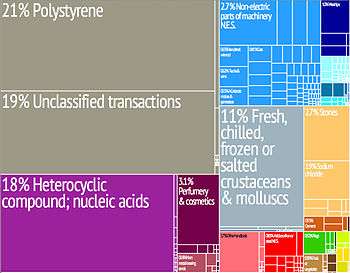

Economy

By the terms of GDP per capita, The Bahamas is one of the richest countries in the Americas.[79] Its currency (the Bahamian dollar) is kept at a 1-to-1 peg with the US dollar.[14] It was revealed in the Panama Papers that The Bahamas is the jurisdiction with the most offshore entities or companies.[80]

Tourism

The Bahamas relies heavily on tourism to generate most of its economic activity. Tourism as an industry not only accounts for about 50% of the Bahamian GDP, but also provides jobs for about half of the country's workforce.[14][81] The Bahamas attracted 5.8 million visitors in 2012, more than 70% of whom were cruise visitors.[82]

Financial services

After tourism, the next most important economic sector is banking and offshore international financial services, accounting for some 15% of GDP.[14]

The government has adopted incentives to encourage foreign financial business, and further banking and finance reforms are in progress. The government plans to merge the regulatory functions of key financial institutions, including the Central Bank of the Bahamas (CBB) and the Securities and Exchange Commission. The Central Bank administers restrictions and controls on capital and money market instruments. The Bahamas International Securities Exchange consists of 19 listed public companies. Reflecting the relative soundness of the banking system (mostly populated by Canadian banks), the impact of the global financial crisis on the financial sector was limited.

The economy has a very competitive tax regime (classified by some as a tax haven). The government derives its revenue from import tariffs, VAT, licence fees, property and stamp taxes, but there is no income tax, corporate tax, capital gains tax, or wealth tax. Payroll taxes fund social insurance benefits and amount to 3.9% paid by the employee and 5.9% paid by the employer.[83] In 2010, overall tax revenue as a percentage of GDP was 17.2%.[1]

Agriculture, natural resources, and manufacturing

Agriculture and manufacturing form the third largest sector of the Bahamian economy, representing 5–7% of total GDP.[14] An estimated 80% of the Bahamian food supply is imported. Major crops include onions, okra, tomatoes, oranges, grapefruit, cucumbers, sugar cane, lemons, limes, and sweet potatoes.[84]

Access to biocapacity in the Bahamas is much higher than world average. In 2016, the Bahamas had 9.2 global hectares [85] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much more than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[86] In 2016 the Bahamas used 3.7 global hectares of biocapacity per person - their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use less biocapacity than the Bahamas contains. As a result, the Bahamas is running a biocapacity reserve.[85]

Demographics

The Bahamas has an estimated population of 385,637, of which 25.9% are 14 or under, 67.2% 15 to 64 and 6.9% over 65. It has a population growth rate of 0.925% (2010), with a birth rate of 17.81/1,000 population, death rate of 9.35/1,000, and net migration rate of −2.13 migrant(s)/1,000 population.[87] The infant mortality rate is 23.21 deaths/1,000 live births. Residents have a life expectancy at birth of 69.87 years: 73.49 years for females, 66.32 years for males. The total fertility rate is 2.0 children born/woman (2010).[1]

The most populous islands are New Providence, where Nassau, the capital and largest city, is located;[88] and Grand Bahama, home to the second largest city of Freeport.[89]

Racial and ethnic groups

According to the 99% response rate obtained from the race question on the 2010 Census questionnaire, 90.6% of the population identified themselves as being Black, 4.7% White and 2.1% of a mixed race (African and European).[90] Three centuries prior, in 1722 when the first official census of The Bahamas was taken, 74% of the population was native European and 26% native African.[90]

Since the colonial era of plantations, Africans or Afro-Bahamians have been the largest ethnic group in The Bahamas, whose primary ancestry was based in West Africa. The first Africans to arrive to The Bahamas were freed slaves from Bermuda; they arrived with the Eleutheran Adventurers looking for new lives.

The Haitian community in The Bahamas is also largely of African descent and numbers about 80,000. Due to an extremely high immigration of Haitians to The Bahamas, the Bahamian government started deporting illegal Haitian immigrants to their homeland in late 2014.[91]

_New_Providence_Creative_Learning_Preschool%2C_Nassau_(25181400074).jpg)

The white Bahamian population are mainly the descendants of the English Puritans and American Loyalists escaping the American Revolution who arrived in 1649 and 1783, respectively.[92] Many Southern Loyalists went to the Abaco Islands, half of whose population was of European descent as of 1985.[93] The term white is usually used to identify Bahamians with Anglo ancestry, as well as "light-skinned" Afro-Bahamians. Sometimes Bahamians use the term Conchy Joe to describe people of Anglo descent.[94]

A small portion of the Euro-Bahamian population are Greek Bahamians, descended from Greek labourers who came to help develop the sponging industry in the 1900s.[95] They make up less than 2% of the nation's population, but have still preserved their distinct Greek Bahamian culture.[96][97]

Bahamians typically identify themselves simply as either black or white.[94]

Religion

Religion in The Bahamas (2010)[98]

The islands' population is predominantly Christian.[14][17] Protestant denominations collectively account for more than 70% of the population, with Baptists representing 35% of the population, Anglicans 15%, Pentecostals 8%, Church of God 5%, Seventh-day Adventists 5% and Methodists 4%. There is also a significant Roman Catholic community accounting for about 14%.[99] There are also smaller communities of Jews, Muslims, Baha'is, Hindus, Rastafarians and practitioners of traditional African religions such as Obeah.

Languages

The official language of The Bahamas is English. Many people speak an English-based creole language called Bahamian dialect (known simply as "dialect") or "Bahamianese".[100] Laurente Gibbs, a Bahamian writer and actor, was the first to coin the latter name in a poem and has since promoted its usage.[101][102] Both are used as autoglossonyms.[103] Haitian Creole, a French-based creole language is spoken by Haitians and their descendants, who make up of about 25% of the total population. It is known simply as Creole[1] to differentiate it from Bahamian English.[104]

Culture

The culture of the islands is a mixture of African (Afro-Bahamians being the largest ethnicity), British (as the former colonial power) and American (as the dominant country in the region and source of most tourists).[17]

A form of African-based folk magic (obeah) is practised by some Bahamians, mainly in the Family Islands (out-islands) of The Bahamas.[105] The practice of obeah is illegal in The Bahamas and punishable by law.[106]

In the less developed outer islands (or Family Islands), handicrafts include basketry made from palm fronds. This material, commonly called "straw", is plaited into hats and bags that are popular tourist items. Another use is for so-called "Voodoo dolls", even though such dolls are the result of foreign influences and not based in historic fact.[107]

Junkanoo is a traditional Afro-Bahamian street parade of 'rushing', music, dance and art held in Nassau (and a few other settlements) every Boxing Day and New Year's Day. Junkanoo is also used to celebrate other holidays and events such as Emancipation Day.[17]

Regattas are important social events in many family island settlements. They usually feature one or more days of sailing by old-fashioned work boats, as well as an onshore festival.

Many dishes are associated with Bahamian cuisine, which reflects Caribbean, African and European influences. Some settlements have festivals associated with the traditional crop or food of that area, such as the "Pineapple Fest" in Gregory Town, Eleuthera or the "Crab Fest" on Andros. Other significant traditions include story telling.

Bahamians have created a rich literature of poetry, short stories, plays and short fictional works. Common themes in these works are (1) an awareness of change, (2) a striving for sophistication, (3) a search for identity, (4) nostalgia for the old ways and (5) an appreciation of beauty. Some major writers are Susan Wallace, Percival Miller, Robert Johnson, Raymond Brown, O.M. Smith, William Johnson, Eddie Minnis and Winston Saunders.[108][109]

Bahamas culture is rich with beliefs, traditions, folklore and legend. The best-known folklore and legends in The Bahamas include the lusca and chickcharney creatures of Andros, Pretty Molly on Exuma Bahamas and the Lost City of Atlantis on Bimini Bahamas.

Sport

Sport is a significant part of Bahamian culture. The national sport is cricket. Cricket has been played in The Bahamas from 1846,[110] the oldest sport being played in the country today. The Bahamas Cricket Association was formed in 1936, and from the 1940s to the 1970s, cricket was played amongst many Bahamians. Bahamas is not a part of the West Indies Cricket Board, so players are not eligible to play for the West Indies cricket team. The late 1970s saw the game begin to decline in the country as teachers, who had previously come from the United Kingdom with a passion for cricket, were replaced by teachers who had been trained in the United States. The Bahamian physical education teachers had no knowledge of the game and instead taught track and field, basketball, baseball, softball,[111] volleyball[112] and Association football[113] where primary and high schools compete against each other. Today cricket is still enjoyed by a few locals and immigrants in the country, usually from Jamaica, Guyana, Haiti and Barbados. Cricket is played on Saturdays and Sundays at Windsor Park and Haynes Oval.

The only other sporting event that began before cricket was horse racing, which started in 1796. The most popular spectator sports are those imported from the United States, such as basketball,[114] American football,[115] and baseball,[116] rather than from the British Isles, due to the country's close proximity to the United States, unlike their other Caribbean counterparts, where cricket, rugby, and netball have proven to be more popular.

Dexter Cambridge, Rick Fox, Ian Lockhart, Magnum Rolle, Buddy Hield and Deandre Ayton are a few Bahamians who joined Bahamian Mychal Thompson of the Los Angeles Lakers in the NBA ranks.[117][118] Over the years American football has become much more popular than soccer, though not implemented in the high school system yet. Leagues for teens and adults have been developed by the Bahamas American Football Federation.[119] However soccer, as it is commonly known in the country, is still a very popular sport amongst high school pupils. Leagues are governed by the Bahamas Football Association. Recently, the Bahamian government has been working closely with Tottenham Hotspur of London to promote the sport in the country as well as promoting The Bahamas in the European market. In 2013, 'Spurs' became the first Premier League club to play an exhibition match in The Bahamas, facing the Jamaican national team. Joe Lewis, the owner of the club, is based in The Bahamas.[120][121][122]

Other popular sports are swimming,[123] tennis[124] and boxing,[125] where Bahamians have enjoyed some degree of success at the international level. Other sports such as golf,[126] rugby league,[127] rugby union,[128] beach soccer,[129] and netball are considered growing sports. Athletics, commonly known as 'track and field' in the country, is the most successful sport by far amongst Bahamians. Bahamians have a strong tradition in the sprints and jumps. Track and field is probably the most popular spectator sport in the country next to basketball due to their success over the years. Triathlons are gaining popularity in Nassau and the Family Islands.

Durward Knowles was a sailor and Olympic champion from The Bahamas. He won the gold medal in the Star class at the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, together with Cecil Cooke. He won the bronze medal in the same class at the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne along with Sloane Elmo Farrington.He had previously competed for the United Kingdom in the 1948 Olympics, finishing in 4th place in the Star class again with Sloane Elmo Farrington. Representing The Bahamas, Knowles won gold in the 1959 Pan American Games star class (with Farrington). He is one of only five athletes who have competed in the Olympics over a span of 40 years.

Bahamians have gone on to win numerous track and field medals at the Olympic Games, IAAF World Championships in Athletics, Commonwealth Games and Pan American Games. Frank Rutherford is the first athletics Olympic medallist for the country. He won a bronze medal for triple jump during the 1992 Summer Olympics.[130] Pauline Davis-Thompson, Debbie Ferguson, Chandra Sturrup, Savatheda Fynes and Eldece Clarke-Lewis teamed up for the first athletics Olympic gold medal for the country when they won the 4 × 100 m relay at the 2000 Summer Olympics. They are affectionately known as the "Golden Girls".[131] Tonique Williams-Darling became the first athletics individual Olympic gold medallist when she won the 400-metre sprint in 2004 Summer Olympics.[132] In 2007, with the disqualification of Marion Jones, Pauline Davis-Thompson was advanced to the gold medal position in the 200 metres at the 2000 Olympics, predating William-Darling.

The Bahamas were hosts of the first men's senior FIFA tournament to be staged in the Caribbean, the 2017 FIFA Beach Soccer World Cup.[133] The Bahamas also hosted the first 3 editions of the IAAF World Relays.

Education

According to 1995 estimates, 98.2% of the Bahamian adult population are literate.

The University of the Bahamas (UB) is the national higher education/tertiary system. Offering baccalaureate, masters and associate degrees, UB has three campuses, and teaching and research centres throughout The Bahamas. The University of the Bahamas was chartered on 10 November 2016.[134]

Transport

The Bahamas contains about 1,620 km (1,010 mi) of paved roads.[13] Inter-island transport is conducted primarily via ship and air. The country has 61 airports, the chief of which are Lynden Pindling International Airport on New Providence, Grand Bahama International Airport on Grand Bahama Island and Leonard M. Thompson International Airport (formerly Marsh Harbour Airport) on Abaco Island.

References

Citations

- Bahamas, The. CIA World Factbook.

- Bahamas Department of Statistics, PDF document retrieved 20 April 2014.

- "Religions in Bahamas - PEW-GRF". www.globalreligiousfutures.org. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "•GENERAL SITUATION AND TRENDS". Pan American Health Organization.

- "Mission to Long Island in the Bahamas". Evangelical Association of the Caribbean.

- "1973: Bahamas' sun sets on British Empire". BBC News. 9 July 1973. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Bahamas".

- Official government website. "The Constitution". Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- "CIA World Factbook – The Bahamas". Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Country Comparison :: GDP – per capita (PPP). CIA World Factbook.

- Peter Barratt (2004). Bahama Saga: The epic story of The Bahama Islands. p. 47.

- Government of the Bahamas "Constitution of The Commonwealth of The Bahamas", Government of The Bahamas, Nassau, 9 July 1973. Retrieved on 18 December 2018.

- "Encyclopedia Britannica – The Bahamas". Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Keegan, William F., 1955– (1992). The people who discovered Columbus : the prehistory of the Bahamas. Jay I. Kislak Reference Collection (Library of Congress). Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 25, 54–8, 86, 170–3. ISBN 0-8130-1137-X. OCLC 25317702.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Markham, Clements R. (1893). The Journal of Christopher Columbus (during His First Voyage, 1492–93). London: The Hakluyt Society. p. 35. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- "Schools Grapple With Columbus's Legacy: Intrepid Explorer or Ruthless Conqueror?", Education Week, 9 October 1991

- Dumene, Joanne E. (1990). "Looking for Columbus". Five Hundred Magazine. 2 (1): 11–15. Archived from the original on 19 September 2008.

- "Diocesan History". Copyright 2009 Anglican Communications Department. 2009. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- Mancke/Shammas p. 255

- Marley (2005), p. 7.

- Marley (1998), p. 226.

- Headlam, Cecil (1930). America and West Indies: July 1716 | British History Online (Vol 29 ed.). London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 139–159. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Woodard, Colin (2010). The Republic of Pirates. Harcourt, Inc. pp. 166–168, 262–314. ISBN 978-0-15-603462-3.

- Dwight C. Hart (2004) The Bahamian parliament, 1729–2004: Commemorating the 275th anniversary Jones Publications, p4

- Hart, p8

- Wertenbaker, Thomas Jefferson (1948). Father Knickerbocker Rebels: New York City during the Revolution. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 260.

- Peters, Thelma (October 1961). "The Loyalist Migration from East Florida to the Bahama Islands". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 40 (2): 123–141. JSTOR 30145777. p. 132, 136, 137

- "Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park", Network to Freedom, National Park Service, 2010, accessed 10 April 2013

- Vignoles, Charles Blacker (1823) Observations on the Floridas, New York: E. Bliss & E. White, pp. 135–136

- Howard, R. (2006). "The "Wild Indians" of Andros Island: Black Seminole Legacy in The Bahamas". Journal of Black Studies. 37 (2): 275. doi:10.1177/0021934705280085.

- Appendix: "Brigs Encomium and Enterprise", Register of Debates in Congress, Gales & Seaton, 1837, pp. 251–253. Note: In trying to retrieve North American slaves off the Encomium from colonial officials (who freed them), the US consul in February 1834 was told by the Lieutenant Governor that "he was acting in regard to the slaves under an opinion of 1818 by Sir Christopher Robinson and Lord Gifford to the British Secretary of State".

- Horne, p. 103

- Horne, p. 137

- Register of Debates in Congress, Gales & Seaton, 1837, The section, "Brigs Encomium and Enterprise", has a collection of lengthy correspondence between US (including M. Van Buren), Vail, the US chargé d'affaires in London, and British agents, including Lord Palmerston, sent to the Senate on 13 February 1837, by President Andrew Jackson, as part of the continuing process of seeking compensation.

- Horne, pp. 107–108

- Williams, Michael Paul (11 February 2002). "Brig Creole slaves". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Grand Bahama Island – American Civil War Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Islands of The Bahamas Official Tourism Site

- Stark, James. Stark's History and Guide to the Bahama Islands (James H. Stark, 1891). pg.93

- Higham, pp. 300–302

- Bloch, Michael (1982). The Duke of Windsor's War, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77947-8, p. 364.

- Higham, pp. 307–309

- Bloch, Michael (1982). The Duke of Windsor's War. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77947-8, pp. 154–159, 230–233

- Higham, pp. 331–332

- Ziegler, Philip (1991). King Edward VIII: The Official Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-57730-2. pp. 471–472

- Matthew, H. C. G. (September 2004; online edition January 2008) "Edward VIII, later Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor (1894–1972)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31061, retrieved 1 May 2010 (Subscription required)

- Higham, p. 359 places the date of his resignation as 15 March, and that he left on 5 April.

- "Bad News for the Boys". Time Magazine. 20 January 1967.

- Nohlen, D. (2005), Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I ISBN 978-0-19-928357-6

- "Bahamian Proposes Independence Move". The Washington Post. United Press International. 19 August 1966. p. A20.

- Bigart, Homer (7 January 1968). "Bahamas Will Ask Britain For More Independence". The New York Times. p. 1.

- Armstrong, Stephen V. (28 September 1968). "Britain and Bahamas Agree on Constitution". The Washington Post. p. A13.

- Hughes, C (1981) Race and Politics in the Bahamas ISBN 978-0-312-66136-6

- "British grant independence to Bahamas". The Baltimore Afro-American. 23 June 1973. p. 22.

- "Bahamas gets deed". Chicago Defender. United Press International. 11 July 1973. p. 3.

- "Bahamas Independence Day Holiday". The Official Site of The Bahamas. The Bahamas Ministry of Tourism. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Bahama Independence". Tri-State Defender. Memphis, Tennessee. 14 July 1973. p. 16.

- Ciferri, Alberto (2019). An Overview of Historical and Socio-Economic Evolution in the Americas. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publisher. p. 313. ISBN 1-5275-3821-4. OCLC 1113890667.

- "Bahamas Joins IMF, World Bank". The Washington Post. 23 August 1973. p. C2.

- Alden, Robert (19 September 1973). "2 Germanys Join U.N. as Assembly Opens 28th Year". The New York Times. p. 1.

- Fitz-Gibbon, Jorge (5 September 2019). "Hurricane Dorian causes $7B in property damage to Bahamas". New York Post. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Stelloh, Tim (9 September 2019). "Hurricane Dorian grows deadlier as more fatalities confirmed in Bahamas". NBC News. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Karimi, Faith; Thornton, Chandler. "1,300 people are listed as missing nearly 2 weeks after Hurricane Dorian hit the Bahamas". CNN. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Rabb, George B. (George Bernard); Hayden, Ellis B.; Expedition (1952-1953), Van Voast-American Museum of Natural History Bahama Islands (1957). "The Van Voast-American Museum of Natural History Bahama Islands Expedition : record of the expedition and general features of the islands. American Museum novitates ; no. 1836". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "40th Anniversary of Snow in South Florida" (PDF). www.weather.gov. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Bahamas". Caribbean Islands. 4 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Hurricane Dorian Advisory Number 33 (Report). NHC.

- "Weather Information for Nassau". worldweather.org.

- "Climatological Information for Nassau, Bahamas (1961–1990)". Hong Kong Observatory.

- Carew, James; Mylroie, John (1997). Vacher, H.L.; Quinn, T. (eds.). Geology of Bahamas, in Geology and Hydrology of Carbonate Islands, Developments in Sedimentology 54. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V. pp. 91–139. ISBN 9780444516442.

- Sealey, Neil (2006). Bahamian Landscapes; An Introduction to the Geology and Physical Geography of The Bahamas. Oxford: Macmillan Education. pp. 1–24. ISBN 9781405064064.

- "Bahamas 1973 (rev. 2002)". Constitute. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Family Island District Councillors & Town Committee Members. Bahamas.gov.bs. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- ASJ-Bahamas National Coat of Arms. Bahamasschools.com. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- ASJ-Bahamas Symbol – Flower. Bahamasschools.com. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- GDP (current US$) | Data | Table. World Bank, Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- "Panama Papers". The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

- "The Bahamas – Economy", Encyclopedia of the Nations, Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- Spencer, Andrew (14 July 2018). Travel and Tourism in the Caribbean: Challenges and Opportunities for Small Island Developing States. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-69581-5.

- "Contributions Table". The National Insurance Board of The Commonwealth of The Bahamas. 11 May 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- Group, Taylor & Francis (2004). Europa World Year. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-85743-254-1.

- "Country Trends". Global Footprint Network. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Lin, David; Hanscom, Laurel; Murthy, Adeline; Galli, Alessandro; Evans, Mikel; Neill, Evan; Mancini, MariaSerena; Martindill, Jon; Medouar, FatimeZahra; Huang, Shiyu; Wackernagel, Mathis (2018). "Ecological Footprint Accounting for Countries: Updates and Results of the National Footprint Accounts, 2012–2018". Resources. 7 (3): 58. doi:10.3390/resources7030058.

- Country Comparison "Total fertility rate", CIA World Factbook.

- "NEW PROVIDENCE". Government of the Bahamas. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- "GRAND BAHAMA". Government of the Bahamas. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- The Commonwealth of the Bahamas (August 2012). "2010 Census of Population and Housing" (PDF). pp. 10 and 82.

In 1722 when the first official census of the Bahamas was taken, 74% of the population was European or native British and 26% was African or mixed. Three centuries later, and according to the 99% response rate obtained from the race question on the 2010 Census questionnaire, 90.6% of the population identified themselves as being Afro-Bahamian, about five percent (4.7%) Euro-Bahamian and two percent (2%) of a mixed race (African and European) and (1%) other races and (1%) not stated.

- Davis, Nick (20 September 2009), "Bahamas outlook clouds for Haitians", BBC.

- "The Names of Loyalist Settlers and Grants of Land Which They Received from the British Government: 1778–1783".

- Christmas, Rachel J. and Christmas, Walter (1984) Fielding's Bermuda and the Bahamas 1985. Fielding Travel Books. p. 158. ISBN 0-688-03965-0

- Schreier, Daniel; Trudgill, Peter; Schneider, Edgar W.; Williams, Jeffrey P., eds. (2010). The Lesser-Known Varieties of English: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9781139487412. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Johnson, Howard (1986), "'Safeguarding our traders': The beginnings of immigration restrictions in the Bahamas, 1925–33", Immigrants and Minorities, 5 (1): 5–27,

- Johnson 1986

- Crain, Edward E. (1994), Historic architecture in the Caribbean Islands, University Press of Florida

- "Religion in Bahamas". Pew Global Religious Futures.

- United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. Bahamas: International Religious Freedom Report 2008.

- Hackert, Stephanie, ed. (2010). "ICE Bahamas: Why and how?" (PDF). University of Augsburg. pp. 41–45. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Staff, ed. (27 February 2013). "SWAA students have accomplished Bahamian playwright, actor and poet Laurente Gibbs as Guest Speaker". Eleuthera News. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Collie, Linda (2003). Preserving Our Heritage: Language Arts, an Integrated Approach, Part 1. Heinemann. pp. 26–29. ISBN 9780435984809. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Michaelis, Susanne Maria; Maurer, Philippe; Haspelmath, Martin; Huber, Magnus, eds. (2013). The Survey of Pidgin and Creole Languages, Volume 1. OUP Oxford. pp. 127–129. ISBN 9780199691401. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Osiapem, Iyabo F., ed. (2006). "Book Review: Urban Bahamian Creole: System and Variation". Journal of English Linguistics. 34 (4): 362–366. doi:10.1177/0075424206292990.

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2005 – Bahamas". United States Department of State. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Practising Obeah, etc.", Ch. 84 Penal Code. laws.bahamas.gov.bs

- Hurbon, Laennec (1995). "American Fantasy and Haitian Vodou." Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Ed. Donald J. Cosentino. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, pp. 181–97.

- Collinwood, Dean W. and Dodge, Steve (1989) Modern Bahamian Society, Caribbean Books, ISBN 0931209013.

- Collinwood, Dean; Phillips, Rick (1990). "The National Literature of the New Bahamas". Weber Studies. 7 (1): 43–62.

- Cricket – Government – Non-Residents. Bahamas.gov.bs. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- Call to continue to develop softball | The Tribune. Tribune242.com (1 February 2013). Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- "Team Bahamas ratified for volleyball championships", The Tribune (12 July 2013). Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- Bahamas – Football Association. Bahamasfa.com. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- The Bahamas Basketball Federation. The Bahamas Basketball Federation. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- Sturupp, Fred (12 July 2018). "American football in The Bahamas poised for a new era of exposure". The Nassau Guardian. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- www.Baseball Bahamas.net. www.Baseball Bahamas.net. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- "The Bahamas Basketball Federation". The Bahamas Basketball Federation. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- Parrish, Gary (16 June 2016). "NBA Mock Draft 2016: Denzel Valentine takes big dive due to possible knee issue". CBSSports.com. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- Fred Sturrup, "American Football Expanding Locally", The Nassau Guardian. 17 June 2011.

- "Jamaica, Spurs ready for Bahamas match". The Bahamas Investor. 11 March 2013. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "The Bahamas to host football match as part of 40th anniversary of independence". The Bahamas Ministry of Tourism. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Luscombe, Richard and Teather, David (22 March 2008). "The East Ender who blew a billion dollars in a day". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2011.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Home. Bahamas Swimming Federation (6 April 2014). Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- Bahamas Tennis. Bahamas Tennis. Mark Knowlesrepresented the Bahamas as #1 in the world in Doubles on the Men's ATP tour. He won many Grand Slams as doubles Specialist over a 25 year professional career. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- "Boxing – Government – Non-Residents". Bahamas.gov.bs. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- "Golf – Government – Non-Residents". Bahamas.gov.bs. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- Rugby – Government – Non-Residents. Bahamas.gov.bs. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- RugbyBahamas —. Rugbybahamas.com. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- FIFA Beach Soccer World Cup 2013 – CONCACAF Qualifier Bahamas. beachsoccer.com

- "Elite Bahamian Education Program – About Us". Frankrutherfordfoundation.com. Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- "Golden Inspiration", The Tribune. (9 August 2012). Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- "Olympic champion Tonique Williams-Darling looks forward to World Athletics Final". International Association of Athletics Federations (26 August 2004). Retrieved on 20 April 2014.

- "Ethics: Executive Committee unanimously supports recommendation to publish report on 2018/2022 FIFA World Cup™ bidding process". FIFA.com. 19 December 2014.

- "History". University of The Bahamas. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

Sources

- Horne, Gerald (2012). Negro Comrades of the Crown: African Americans and the British Empire Fight the U.S. Before Emancipation. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4463-5.

- Higham, Charles (1988). The Duchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0471485230.

Further reading

General history

- Cash Philip et al. (Don Maples, Alison Packer). The Making of The Bahamas: A History for Schools. London: Collins, 1978.

- Miller, Hubert W. The Colonization of The Bahamas, 1647–1670, The William and Mary Quarterly 2 no.1 (January 1945): 33–46.

- Craton, Michael. A History of The Bahamas. London: Collins, 1962.

- Craton, Michael and Saunders, Gail. Islanders in the Stream: A History of the Bahamian People. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992

- Collinwood, Dean. "Columbus and the Discovery of Self," Weber Studies, Vol. 9 No. 3 (Fall) 1992: 29–44.

- Dodge, Steve. Abaco: The History of an Out Island and its Cays, Tropic Isle Publications, 1983.

- Dodge, Steve. The Compleat Guide to Nassau, White Sound Press, 1987.

- Boultbee, Paul G. The Bahamas. Oxford: ABC-Clio Press, 1990.

- Wood, David E., comp., A Guide to Selected Sources to the History of the Seminole Settlements of Red Bays, Andros, 1817–1980, Nassau: Department of Archives

Economic history

- Johnson, Howard. The Bahamas in Slavery and Freedom. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishing, 1991.

- Johnson, Howard. The Bahamas from Slavery to Servitude, 1783–1933. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1996.

- Alan A. Block. Masters of Paradise, New Brunswick and London, Transaction Publishers, 1998.

- Storr, Virgil H. Enterprising Slaves and Master Pirates: Understanding Economic Life in the Bahamas. New York: Peter Lang, 2004.

Social history

- Johnson, Wittington B. Race Relations in the Bahamas, 1784–1834: The Nonviolent Transformation from a Slave to a Free Society, Fayetteville: University of Arkansas, 2000.

- Shirley, Paul. "Tek Force Wid Force", History Today 54, no. 41 (April 2004): 30–35.

- Saunders, Gail. The Social Life in the Bahamas 1880s–1920s. Nassau: Media Publishing, 1996.

- Saunders, Gail. Bahamas Society After Emancipation. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishing, 1990.

- Curry, Jimmy. Filthy Rich Gangster/First Bahamian Movie. Movie Mogul Pictures: 1996.

- Curry, Jimmy. To the Rescue/First Bahamian Rap/Hip Hop Song. Royal Crown Records, 1985.

- Collinwood, Dean. The Bahamas Between Worlds, White Sound Press, 1989.

- Collinwood, Dean and Steve Dodge. Modern Bahamian Society, Caribbean Books, 1989.

- Dodge, Steve, Robert McIntire and Dean Collinwood. The Bahamas Index, White Sound Press, 1989.

- Collinwood, Dean. "The Bahamas," in The Whole World Handbook 1992–1995, 12th ed., New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994.

- Collinwood, Dean. "The Bahamas," chapters in Jack W. Hopkins, ed., Latin American and Caribbean Contemporary Record, Vols. 1,2,3,4, Holmes and Meier Publishers, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986.

- Collinwood, Dean. "Problems of Research and Training in Small Islands with a Social Science Faculty," in Social Science in Latin America and the Caribbean, UNESCO, No. 48, 1982.

- Collinwood, Dean and Rick Phillips, "The National Literature of the New Bahamas," Weber Studies, Vol.7, No. 1 (Spring) 1990: 43–62.

- Collinwood, Dean. "Writers, Social Scientists and Sexual Norms in the Caribbean," Tsuda Review, No. 31 (November) 1986: 45–57.

- Collinwood, Dean. "Terra Incognita: Research on the Modern Bahamian Society," Journal of Caribbean Studies, Vol. 1, Nos. 2–3 (Winter) 1981: 284–297.

- Collinwood, Dean and Steve Dodge. "Political Leadership in the Bahamas", The Bahamas Research Institute, No.1, May 1987.

External links

- Official website

- "Bahamas". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- The Bahamas from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- The Bahamas at Curlie

- The Bahamas from the BBC News

- Key Development Forecasts for The Bahamas from International Futures

- Maps of the Bahamas from the American Geographical Society Library

.jpg)