Cuba

Cuba (/ˈkjuːbə/ (![]()

![]()

Republic of Cuba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital and largest city | Havana 23°8′N 82°23′W |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Ethnic groups (2012)[3] | |

| Religion (2010) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Cuban |

| Government | Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic[5] |

| Raúl Castro | |

| Miguel Díaz-Canel | |

| Salvador Valdés Mesa | |

• Second Secretary of the Communist Party | José Machado Ventura |

| Manuel Marrero Cruz | |

| Esteban Lazo Hernández | |

| Legislature | National Assembly of People's Power |

| Independence | |

• Declaration of Independence | 10 October 1868 |

| 24 February 1895 | |

| 10 December 1898 | |

• Republic declared (independence from United States) | 20 May 1902 |

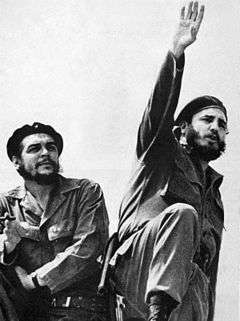

| 26 July 1953 – 1 January 1959 | |

• Current constitution | 10 April 2019 |

| Area | |

• Total | 109,884 km2 (42,426 sq mi) (104th) |

• Water (%) | 0.94 |

| Population | |

• 2019 census | |

• Density | 101.9/km2 (263.9/sq mi) (81st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | US$ 254.865 billion[7] |

• Per capita | US$ 22,237[7][8] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2000) | 38.0[11] medium |

| HDI (2018) | high · 72nd |

| Currency | (CUC) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (CST) |

| UTC−4 (CDT) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +53 |

| ISO 3166 code | CU |

| Internet TLD | .cu |

Website www | |

| |

The territory that is now Cuba was inhabited by the Ciboney Taíno people from the 4th millennium BC until Spanish colonization in the 15th century.[14] From the 15th century, it was a colony of Spain until the Spanish–American War of 1898, when Cuba was occupied by the United States and gained nominal independence as a de facto United States protectorate in 1902. As a fragile republic, in 1940 Cuba attempted to strengthen its democratic system, but mounting political radicalization and social strife culminated in a coup and subsequent dictatorship under Fulgencio Batista in 1952.[15] Open corruption and oppression under Batista's rule led to his ousting in January 1959 by the 26th of July Movement, which afterwards established communist rule under the leadership of Fidel Castro.[16][17][18] Since 1965, the state has been governed by the Communist Party of Cuba. The country was a point of contention during the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States, and a nuclear war nearly broke out during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. Cuba is one of a few extant Marxist–Leninist socialist states, where the role of the vanguard Communist Party is enshrined in the Constitution. Independent observers have accused the Cuban government of numerous human rights abuses, including short-term arbitrary imprisonment.[19]

Massive Soviet military assistance enabled Cuba to project power abroad. It was involved in a broad range of military and humanitarian activities in Guinea-Bissau, Syria, Angola, Algeria, South Yemen, North Vietnam, Laos, Zaire, Iraq, Libya, Zanzibar, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia, Congo-Brazzaville, Sierra Leone, Cape Verde, Nigeria, Benin, Cameroon, Zimbabwe and Mozambique.[20] Cuba sent more than 300,000 of its citizens to fight in Angola (1975–91) and defeated South Africa's armed forces in conventional warfare involving tanks, planes, and artillery.[21] Cuban intervention in Angola contributed to the downfall of the apartheid regime in South Africa.[22] The presence of a substantial number of blacks and mulattos in the Cuban forces (40–50 percent in Angola)[23] helped give teeth to Castro's campaign against racism and related prejudice like xenophobia.

Culturally, Cuba is considered part of Latin America.[24] It is a multiethnic country whose people, culture and customs derive from diverse origins, including the aboriginal Taíno and Ciboney peoples, the long period of Spanish colonialism, the introduction of African slaves and a close relationship with the Soviet Union in the Cold War. The population of Cuba is 51% mulatto (of mixed European and African lineage), 37% white, 11% black and 1% Chinese.[25] From 1962 until 1992, Cuba was officially an atheist Republic, openly and categorically hostile to religion.[26]

Cuba is a sovereign state and a founding member of the United Nations, the G77, the Non-Aligned Movement, the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States, ALBA and Organization of American States. It has currently one of the world's only planned economies, and its economy is dominated by the tourism industry and the exports of skilled labor, sugar, tobacco, and coffee. According to the Human Development Index, Cuba has high human development and is ranked the eighth highest in North America, though 72nd in the world in 2019.[27] It also ranks highly in some metrics of national performance, including health care and education.[28][29] It is the only country in the world to meet the conditions of sustainable development put forth by the WWF.[30]

Etymology

Historians believe the name Cuba comes from the Taíno language, however "its exact derivation [is] unknown".[31] The exact meaning of the name is unclear but it may be translated either as 'where fertile land is abundant' (cubao),[32] or 'great place' (coabana).[33]

Fringe theory writers who believe that Christopher Columbus was Portuguese state that Cuba was named by Columbus for the town of Cuba in the district of Beja in Portugal.[34][35]

History

Pre-Columbian era

Before the arrival of the Spanish, Cuba was inhabited by three distinct tribes of indigenous peoples of the Americas. The Taíno (an Arawak people), the Guanahatabey and the Ciboney people.

The ancestors of the Ciboney migrated from the mainland of South America, with the earliest sites dated to 5,000 BP.[36]

The Taíno arrived from Hispaniola sometime in the 3rd century A.D. When Columbus arrived they were the dominant culture in Cuba, having an estimated population of 150,000.[36]

The Taíno were farmers, while the Ciboney were farmers as well as fishers and hunter-gatherers.

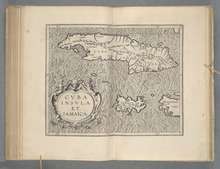

Spanish colonization and rule (1492–1898)

After first landing on an island then called Guanahani, Bahamas, on 12 October 1492,[37] Christopher Columbus commanded his three ships: La Pinta, La Niña and the Santa María, to land on Cuba's northeastern coast on 28 October 1492.[38] (This was near what is now Bariay, Holguín Province.) Columbus claimed the island for the new Kingdom of Spain[39] and named it Isla Juana after Juan, Prince of Asturias.[40]

In 1511, the first Spanish settlement was founded by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar at Baracoa. Other towns soon followed, including San Cristobal de la Habana, founded in 1515, which later became the capital. The native Taíno were forced to work under the encomienda system,[41] which resembled a feudal system in Medieval Europe.[42] Within a century the indigenous people were virtually wiped out due to multiple factors, primarily Eurasian infectious diseases, to which they had no natural resistance (immunity), aggravated by harsh conditions of the repressive colonial subjugation.[43] In 1529, a measles outbreak in Cuba killed two-thirds of those few natives who had previously survived smallpox.[44][45]

On 18 May 1539, Conquistador Hernando de Soto departed from Havana at the head of some 600 followers into a vast expedition through the Southeastern United States, starting at La Florida, in search of gold, treasure, fame and power.[46] On 1 September 1548, Dr. Gonzalo Perez de Angulo was appointed governor of Cuba. He arrived in Santiago, Cuba on 4 November 1549 and immediately declared the liberty of all natives.[47] He became Cuba's first permanent governor to reside in Havana instead of Santiago, and he built Havana's first church made of masonry.[48] After the French took Havana in 1555, the governor's son, Francisco de Angulo, went to Mexico.[49]

Cuba developed slowly and, unlike the plantation islands of the Caribbean, had a diversified agriculture. But what was most important was that the colony developed as an urbanized society that primarily supported the Spanish colonial empire. By the mid-18th century, its colonists held 50,000 slaves, compared to 60,000 in Barbados; 300,000 in Virginia, both British colonies; and 450,000 in French Saint-Domingue, which had large-scale sugar cane plantations.[50]

The Seven Years' War, which erupted in 1754 across three continents, eventually arrived in the Spanish Caribbean. Spain's alliance with the French pitched them into direct conflict with the British, and in 1762 a British expedition of five warships and 4,000 troops set out from Portsmouth to capture Cuba. The British arrived on 6 June, and by August had Havana under siege.[51] When Havana surrendered, the admiral of the British fleet, George Pocock and the Commander of the Land Forces George Keppel, the 3rd Earl of Albemarle, entered the city as a conquering new governor and took control of the whole western part of the island. The British immediately opened up trade with their North American and Caribbean colonies, causing a rapid transformation of Cuban society. They imported food, horses and other goods into the city, as well as thousands of slaves from West Africa to work on the underdeveloped sugar plantations.[51]

Though Havana, which had become the third-largest city in the Americas, was to enter an era of sustained development and increasing ties with North America during this period, the British occupation of the city proved short-lived. Pressure from London sugar merchants, fearing a decline in sugar prices, forced negotiations with the Spanish over colonial territories. Less than a year after Britain seized Havana, it signed the Peace of Paris together with France and Spain, ending the Seven Years' War. The treaty gave Britain Florida in exchange for Cuba. The French had recommended this to Spain, advising that declining to give up Florida could result in Spain instead losing Mexico and much of the South American mainland to the British.[51] In the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), General Bernardo de Gálvez, the Spanish governor of Louisiana, reconquered Florida for Spain with Mexican, Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Cuban soldiers.[52]

The real engine for the growth of Cuba's commerce in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was the Haitian Revolution. When the enslaved peoples of what had been the Caribbean's richest colony freed themselves through violent revolt, Cuban planters perceived the region's changing circumstances with both a sense of fear and opportunity. They were afraid because of the prospect that slaves might revolt in Cuba, too, and numerous prohibitions during the 1790s on the sale of slaves in Cuba that had previously been slaves in French colonies underscored this anxiety. The planters saw opportunity, however, because they thought that they could exploit the situation by transforming Cuba into the slave society and sugar-producing "pearl of the Antilles" that Haiti had been before the revolution.[53] As the historian Ada Ferrer has written, "At a basic level, liberation in Saint-Domingue helped entrench its denial in Cuba. As slavery and colonialism collapsed in the French colony, the Spanish island underwent transformations that were almost the mirror image of Haiti's."[54] Estimates suggest that between 1790 and 1820 some 325,000 Africans were imported to Cuba as slaves, which was four times the amount that had arrived between 1760 and 1790.[55] Although a smaller proportion of the population of Cuba was enslaved, at times slaves arose in revolt. In 1812 the Aponte Slave Rebellion took place but it was suppressed.[56]

The population of Cuba in 1817 was 630,980, of which 291,021 were white, 115,691 free people of color (mixed-race), and 224,268 black slaves.[57] This was a much higher proportion of free blacks to slaves than in Virginia, for instance, or the other Caribbean islands. Historians such as Swedish Magnus Mõrner, who studied slavery in Latin America, found that manumissions increased when slave economies were in decline, as in 18th-century Cuba and early 19th-century Maryland of the United States.[50][58] In part due to Cuban slaves working primarily in urbanized settings, by the 19th century, there had developed the practice of coartacion, or "buying oneself out of slavery", a "uniquely Cuban development", according to historian Herbert S. Klein.[59] Due to a shortage of white labor, blacks dominated urban industries "to such an extent that when whites in large numbers came to Cuba in the middle of the nineteenth century, they were unable to displace Negro workers."[50] A system of diversified agriculture, with small farms and fewer slaves, served to supply the cities with produce and other goods.[50] In the 1820s, when the rest of Spain's empire in Latin America rebelled and formed independent states, Cuba remained loyal. Its economy was based on serving the empire. By 1860, Cuba had 213,167 free people of color, 39% of its non-white population of 550,000.[50] By contrast, Virginia, with about the same number of blacks, had only 58,042 or 11% who were free; the rest were enslaved.[50]

Independence movements

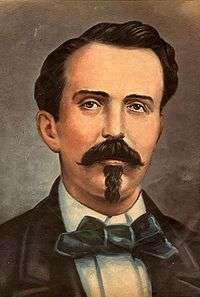

The Dominican Restoration War (1863–65) deepened economic and fiscal problems in Cuba because the Bourbon regime forced Cubans to help pay debts run up during the expensive conflict by imposing a tax on income and property in Cuba in 1867.[61] This eventually led to a rebellion in 1868 led by planter Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. De Céspedes, a sugar planter, freed his slaves to fight with him for an independent Cuba. On 27 December 1868, he issued a decree condemning slavery in theory but accepting it in practice and declaring free any slaves whose masters present them for military service.[62] The 1868 rebellion resulted in a prolonged conflict known as the Ten Years' War. Both sides in this brutal war committed atrocities.[63] A great number of the rebels were volunteers from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and the United States, as well as numerous Chinese indentured servants.[64] A battalion of 500 Chinese fought under the command of Dominican General Máximo Gómez in the 1874 Battle of Las Guasimas.[65] A monument in Havana honors the Cuban Chinese who fell in the war.[66]

A group of Dominican white and light-skinned mulattos,[67] led by Máximo Gómez, Luis Marcano, and Modesto Díaz, utilizing the experience they had gained in the Dominican war against Spain, became instructors of military strategy and tactics. With reinforcements and guidance from the Dominicans, the Cubans defeated Spanish detachments, cut railway lines, and gained dominance over vast sections of the eastern portion of the island.[68] On 19 February 1874, Gómez and 700 other rebels marched westward from their eastern base and defeated 2,000 Spanish troops at El Naranjo. The Spaniards lost 100 killed and 200 wounded and the rebels a total of 150 killed and wounded.[64] The most significant rebel victory came at the Battle of Las Guasimas, 16–20 March 1874, when 2,050 rebels, led by Antonio Maceo and Gómez, defeated 5,000 Spanish troops with 6 cannons. The five-day battle cost the Spanish 1,037 casualties and the rebels 174 casualties.[64] The Spanish built a fortified line (La Trocha) to prevent Gómez to move westward from Oriente province;[69] it consisted of numerous small forts, wire fences and a parallel railroad line. It was the largest Spanish fortification in the New World.[70] Gómez began an invasion of Western Cuba in 1875, but the vast majority of slaves and wealthy sugar producers in the region did not join the revolt. After his most trusted general, the American Henry Reeve, was killed in 1876, the invasion was over. By that year, the Spanish government had deployed more than 250,000 troops to Cuba, as the end of the Third Carlist War had freed up Spanish soldiers for the suppression of the revolt.

The United States declined to recognize the new Cuban government, although many European and Latin American nations did so.[71] In 1878, the Pact of Zanjón ended the conflict, with Spain promising greater autonomy to Cuba. Spain sustained 200,000 casualties, mostly from disease; the rebels sustained 100,000–150,000 dead and the island sustained over $300 million in property damage.[72] In 1879–80, Cuban patriot Calixto García attempted to start another war known as the Little War but did not receive enough support.[73] Slavery in Cuba was abolished in 1875 but the process was completed only in 1886.[74][75]

An exiled dissident named José Martí founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in New York in 1892. The aim of the party was to achieve Cuban independence from Spain.[76] In January 1895 Martí traveled to Montecristi and Santo Domingo to join the efforts of Máximo Gómez.[76] Martí recorded his political views in the Manifesto of Montecristi.[77] Fighting against the Spanish army began in Cuba on 24 February 1895, but Martí was unable to reach Cuba until 11 April 1895.[76] Martí was killed in the Battle of Dos Rios on 19 May 1895.[76] His death immortalized him as Cuba's national hero.[77]

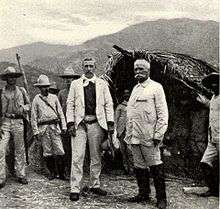

Around 200,000 Spanish troops outnumbered the much smaller rebel army, which relied mostly on guerrilla and sabotage tactics. The Spaniards began a campaign of suppression. General Valeriano Weyler, military governor of Cuba, herded the rural population into what he called reconcentrados, described by international observers as "fortified towns". These are often considered the prototype for 20th-century concentration camps.[78] Between 200,000[79] and 400,000 Cuban civilians died from starvation and disease in the barbed wire concentration camps, numbers verified by the Red Cross and United States Senator Redfield Proctor, a former Secretary of War. American and European protests against Spanish conduct on the island followed.[80]

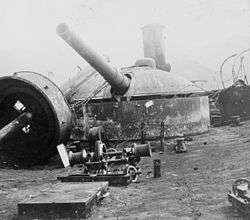

The U.S. battleship Maine was sent to protect U.S. interests, but soon after arrival, it exploded in Havana harbor and sank quickly, killing nearly three quarters of the crew. The cause and responsibility for the sinking of the ship remained unclear after a board of inquiry. Popular opinion in the U.S., fueled by an active press, concluded that the Spanish were to blame and demanded action.[81] Spain and the United States declared war on each other in late April 1898. Over the previous decades, five U.S. presidents—Polk, Pierce, Buchanan, Grant, and McKinley—had tried to buy the island of Cuba from Spain.[82][83]

From 22–24 June, the U.S. V Corps under General William R. Shafter landed at Daiquirí and Siboney, east of Santiago, and established an American base of operations. A contingent of Spanish troops, having fought a skirmish with the Americans near Siboney on 23 June, had retired to their lightly entrenched positions at Las Guasimas. An advance guard of U.S. forces under former Confederate General Joseph Wheeler ignored Cuban scouting parties and orders to proceed with caution. They caught up with and engaged the Spanish rearguard of 1,500 soldiers led by General Antero Rubín who effectively ambushed them, in the Battle of Las Guasimas on 24 June. The Americans lost 16 killed and 52 wounded. The Spanish lost 12 dead and 24 wounded.[84] On 1 July, a force of 15,065 American troops in regular infantry and cavalry regiments attacked 1,320 entrenched Spaniards in dangerous Civil War-style frontal assaults at the Battle of El Caney and Battle of San Juan Hill outside of Santiago, which cost the Americans 225 killed in action, 1,384 wounded in action, and 72 missing in action.[84] At all battle sites on 1 July, the Spanish lost 215 killed, 376 wounded, and 200 captured.[84]

After the battles of San Juan Hill and El Caney, the American advance halted. Spanish troops successfully defended Fort Canosa, allowing them to stabilize their line and bar the entry to Santiago. The Americans and Cubans forcibly began a siege of the city. During the nights, Cuban troops dug successive series of "trenches" (raised parapets), toward the Spanish positions. Once completed, these parapets were occupied by U.S. soldiers and a new set of excavations went forward. The Spanish forces surrendered on 17 July; 30,000 POWs were taken at Santiago and other places in Oriente, along with 100 cannons, and 19 machine guns.[84]

Republic (1902–1959)

First years (1902–1925)

After the Spanish–American War, Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris (1898), by which Spain ceded Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam to the United States for the sum of US$20 million[85] and Cuba became a protectorate of the United States. Cuba gained formal independence from the U.S. on 20 May 1902, as the Republic of Cuba.[86] Under Cuba's new constitution, the U.S. retained the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and to supervise its finances and foreign relations. Under the Platt Amendment, the U.S. leased the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base from Cuba.

Following disputed elections in 1906, the first president, Tomás Estrada Palma, faced an armed revolt by independence war veterans who defeated the meager government forces.[87] The U.S. intervened by occupying Cuba and named Charles Edward Magoon as Governor for three years. Cuban historians have characterized Magoon's governorship as having introduced political and social corruption.[88] In 1908, self-government was restored when José Miguel Gómez was elected President, but the U.S. continued intervening in Cuban affairs. In 1912, the Partido Independiente de Color attempted to establish a separate black republic in Oriente Province,[89] but was suppressed by General Monteagudo with considerable bloodshed.

In 1924, Gerardo Machado was elected president.[90] During his administration, tourism increased markedly, and American-owned hotels and restaurants were built to accommodate the influx of tourists.[90] The tourist boom led to increases in gambling and prostitution in Cuba.[90] The Wall Street Crash of 1929 led to a collapse in the price of sugar, political unrest, and repression.[91] Protesting students, known as the Generation of 1930, turned to violence in opposition to the increasingly unpopular Machado.[91] A general strike (in which the Communist Party sided with Machado),[92] uprisings among sugar workers, and an army revolt forced Machado into exile in August 1933. He was replaced by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada.[91]

Revolution of 1933–1940

In September 1933, the Sergeants' Revolt, led by Sergeant Fulgencio Batista, overthrew Cespedes.[93] A five-member executive committee (the Pentarchy of 1933) was chosen to head a provisional government.[94] Ramón Grau San Martín was then appointed as provisional president.[94] Grau resigned in 1934, leaving the way clear for Batista, who dominated Cuban politics for the next 25 years, at first through a series of puppet-presidents.[93] The period from 1933 to 1937 was a time of "virtually unremitting social and political warfare".[95] On balance, during the period 1933–40 Cuba suffered from fragile politic structures, reflected in the fact that it saw three different presidents in two years (1935–36), and in the militaristic and repressive policies of Batista as Head of the Army.

Constitution of 1940

A new constitution was adopted in 1940, which engineered radical progressive ideas, including the right to labor and health care.[96] Batista was elected president in the same year, holding the post until 1944.[97] He is so far the only non-white Cuban to win the nation's highest political office.[98][99][100] His government carried out major social reforms. Several members of the Communist Party held office under his administration.[101] Cuban armed forces were not greatly involved in combat during World War II—though president Batista did suggest a joint U.S.-Latin American assault on Francoist Spain to overthrow its authoritarian regime.[102] Cuba lost six merchant ships during the war, and the Cuban Navy was credited with sinking the German submarine U-176.[103]

Batista adhered to the 1940 constitution's strictures preventing his re-election.[104] Ramon Grau San Martin was the winner of the next election, in 1944.[97] Grau further corroded the base of the already teetering legitimacy of the Cuban political system, in particular by undermining the deeply flawed, though not entirely ineffectual, Congress and Supreme Court.[105] Carlos Prío Socarrás, a protégé of Grau, became president in 1948.[97] The two terms of the Auténtico Party brought an influx of investment, which fueled an economic boom, raised living standards for all segments of society, and created a middle class in most urban areas.[106]

After finishing his term in 1944 Batista lived in Florida, returning to Cuba to run for president in 1952. Facing certain electoral defeat, he led a military coup that preempted the election.[107] Back in power, and receiving financial, military, and logistical support from the United States government,[108] Batista suspended the 1940 Constitution and revoked most political liberties, including the right to strike. He then aligned with the wealthiest landowners who owned the largest sugar plantations, and presided over a stagnating economy that widened the gap between rich and poor Cubans.[109] Batista outlawed the Cuban Communist Party in 1952.[110] After the coup, Cuba had Latin America's highest per capita consumption rates of meat, vegetables, cereals, automobiles, telephones and radios, though about one third of the population was considered poor and enjoyed relatively little of this consumption.[111]

In 1958, Cuba was a relatively well-advanced country by Latin American standards, and in some cases by world standards.[112] On the other hand, Cuba was affected by perhaps the largest labor union privileges in Latin America, including bans on dismissals and mechanization. They were obtained in large measure "at the cost of the unemployed and the peasants", leading to disparities.[113] Between 1933 and 1958, Cuba extended economic regulations enormously, causing economic problems.[98][114] Unemployment became a problem as graduates entering the workforce could not find jobs.[98] The middle class, which was comparable to that of the United States, became increasingly dissatisfied with unemployment and political persecution. The labor unions supported Batista until the very end.[98][99] Batista stayed in power until he was forced into exile in December 1958.[115]

Revolution and Communist party rule (1959–present)

In the 1950s, various organizations, including some advocating armed uprising, competed for public support in bringing about political change.[116] In 1956, Fidel Castro and about 80 supporters landed from the yacht Granma in an attempt to start a rebellion against the Batista government.[116] It was not until 1958 that Castro's 26th of July Movement emerged as the leading revolutionary group.[116] Batista's troops were defeated by Castro's fighters at the Battle of La Plata (11–21 July 1958). Although Batista's army gained a victory at the Battle of Las Mercedes (29 July–8 August 1958), the army commander allowed the rebels to escape back into the Sierra Maestra mountains. By late 1958, the rebels had broken out of the Sierra Maestra and launched a general popular insurrection. They subsequently seized significant amounts of Dominican-made Cristóbal Carbines and hand grenades.[117] After suffering a crucial defeat at the Battle of Santa Clara, Batista fled with his family to the Dominican Republic on 1 January 1959. Later he went into exile on the Portuguese island of Madeira and finally settled in Estoril, near Lisbon. Fidel Castro's forces entered the capital on 8 January 1959. The liberal Manuel Urrutia Lleó became the provisional president.[118]

After Dominican Republic strongman Rafael Trujillo formed an anti-Castro Foreign Legion of 3,000 soldiers of fortune, including 200 former Batista soldiers and 400 Spanish veterans of Francisco Franco's World War II Blue Division,[119] Castro sponsored or organized several attempts to unseat him.[120][121][122] Castro feared a possible attack from the Dominican Republic and was determined to acquire jet aircraft as a preventive measure: Cuba's ability to repel an air attack was very precarious, since the Dominicans possessed 40 jet aircraft whereas Cuba had only one.[123]

Militant anti-Castro groups, funded by exiles, by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and by Trujillo's Dominican government, carried out armed attacks and set up guerrilla bases in the Escambray Mountains. This led to a failed rebellion, which lasted longer and involved more soldiers than the Cuban Revolution.[124][125] Castro took up Weyler's tactics. Near 1,000 families were forcibly uprooted from the Escambray countryside, leaving the rebels without their habitat to support them; the uprooted men were sent to prisons and forced labor camps throughout Cuba.

The United States Department of State estimated that 3,200 people were executed from 1959 to 1962.[126] According to Amnesty International, official death sentences from 1959–87 numbered 237 of which all but 21 were actually carried out.[127] Other estimates for the total number of political executions range from 4,000 to 33,000.[128][129][130] The vast majority of those executed directly following the 1959 revolution were policemen, politicians, and informers of the Batista regime accused of crimes such as torture and murder, and their public trials and executions had widespread popular support among the Cuban population.[131]

The United States government initially reacted favorably to the Cuban revolution, seeing it as part of a movement to bring democracy to Latin America.[133] Castro's legalization of the Communist party and the hundreds of executions of Batista agents, policemen and soldiers that followed caused a deterioration in the relationship between the two countries.[133] The promulgation of the Agrarian Reform Law, expropriating thousands of acres of farmland (including from large U.S. landholders), further worsened relations.[133][134] In response, between 1960 and 1964 the U.S. imposed a range of sanctions, eventually including a total ban on trade between the countries and a freeze on all Cuban-owned assets in the U.S.[135] In February 1960, Castro signed a commercial agreement with Soviet Vice-Premier Anastas Mikoyan.[133]

In March 1960, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower gave his approval to a CIA plan to arm and train a group of Cuban refugees to overthrow the Castro regime.[136] The invasion (known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion) took place on 14 April 1961, during the term of President John F. Kennedy.[134] About 1,400 Cuban exiles disembarked at the Bay of Pigs, but failed in their attempt to overthrow Castro.[134] In January 1962, Cuba was suspended from the Organization of American States (OAS), and later the same year the OAS started to impose sanctions against Cuba of similar nature to the U.S. sanctions.[137] The Cuban Missile Crisis (October 1962) almost sparked World War III.

In 1962, Castro officially declared Cuba an atheist state and shut down more than 400 Catholic schools, claiming that they spread dangerous beliefs among the people.[138] By 1963, Cuba was moving towards a full-fledged Communist system modeled on the USSR.[139] In 1963, Cuba assisted Algeria in the Sand War against Morocco.[140] Cuba sent 300–400 tank troops and some 40 Russian-built T-34 tanks, which engaged in combat.[141] In 1964, Cuba organized a meeting of Latin American communists in Havana and stoked a civil war in the Dominican Republic in 1965 that prompted the U.S. military to intervene there.[142] Che Guevara engaged in guerrilla activities in Congo and was killed in 1967 while attempting to start a revolution in Bolivia.[142] In the early 1970s, the USSR emerged as the dominant political force in Cuba. The Yom Kippur War (1973) was the first case where regular Cuban forces were employed in the service of Soviet foreign policy.[143] Israeli sources reported the presence of a Cuban armored brigade in the Golan Heights.[144] Following the disengagement agreement on 18 January 1974, the brigade was transferred to the front to reinforce Syrian forces on the Hermon Mountain. With the resumption of hostilities, the Cuban forces took an active part in the fighting against Israel. The Cubans remained in Syria for more than a year after the termination of hostilities, until they were flown to Angola in the autumn of 1975.[145]

In November 1975, Cuba dispatched thousands of combat troops to Angola to support the pro-Soviet MPLA. By February 1976, the Cubans had all but defeated FNLA, Zaireans, UNITA, and South Africa.[146] Cuba sustained 500 military fatalities in the conventional war.[147] FLEC irregulars fought the Cubans but were defeated. Comrade Jonas Savimbi, the President of UNITA, writing from the party's mobile headquarters inside Angola on 1 October 1976, stated:

North-South, East-West, Angola has become a vast cemetery: the Cubans are killing, raping women, and oppressing the survivors just like the Portuguese during colonialism.[148]

There were also incidents of Cuban troops bursting into churches and forcing congregation members to bow and worship before Soviet assault rifles.[149] In late 1977, Cuba sent 16,000 regular troops to Ethiopia, assisted by mechanized Soviet battalions, to help defeat a Somali invasion.[150] By March 1978, following months of tank warfare, a combined force of Ethiopian and Cuban troops (led by Russian and Cuban officers) repulsed the enemy.[151] From July 1975–July 1978, Cuban casualties in its African wars (Angola and Ethiopia) totaled 5,600, including 1,400 killed—1,000 in Angola and 400 in Ethiopia.[152] In 1987–88, South Africa again sent military forces to Angola, and several inconclusive battles were fought between Cuban and apartheid forces.[153] Cuba, Angola and South Africa signed the Tripartite Accord on 22 December 1988, in which Cuba agreed to withdraw troops from Angola in exchange for South Africa withdrawing soldiers from Angola and South West Africa.

The standard of living in the 1970s was "extremely spartan" and discontent was rife.[154] Fidel Castro admitted the failures of economic policies in a 1970 speech.[154] In 1975, the OAS lifted its sanctions against Cuba, with the approval of 16 member states, including the U.S. The U.S., however, maintained its own sanctions.[137] In 1979, the U.S. objected to the presence of Soviet combat troops on the island.[142] In 1982, Cuban construction workers began building an airfield in Grenada. U.S. forces invaded Grenada in 1983, killing more than two dozen Cubans and expelling the remainder of the Cuban aid force from the island.[142] Cuba gradually withdrew its troops from Angola in 1989–91. It suffered up to 18,000 casualties (3,000 dead and 15,000 wounded) during the Angolan intervention.[155]

Soviet troops began to withdraw from Cuba in September 1991,[142] and Castro's rule was severely tested in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse in December 1991 (known in Cuba as the Special Period). The country faced a severe economic downturn following the withdrawal of Soviet subsidies worth $4 billion to $6 billion annually, resulting in effects such as food and fuel shortages.[156][157] The government did not accept American donations of food, medicines, and cash until 1993.[156] On 5 August 1994, state security dispersed protesters in a spontaneous protest in Havana.[158]

Cuba has since found a new source of aid and support in the People's Republic of China. In addition, Hugo Chávez, then-President of Venezuela, and Evo Morales, President of Bolivia, became allies and both countries are major oil and gas exporters. In 2003, the government arrested and imprisoned a large number of civil activists, a period known as the "Black Spring".[159][160]

In February 2008, Fidel Castro announced his resignation as President of Cuba following the onset of his reported serious gastrointestinal illness in July 2006.[161] On 24 February his brother, Raúl Castro, was declared the new President.[162] In his inauguration speech, Raúl promised that some of the restrictions on freedom in Cuba would be removed.[163] In March 2009, Raúl Castro removed some of his brother's appointees.[164]

On 3 June 2009, the Organization of American States adopted a resolution to end the 47-year ban on Cuban membership of the group.[165] The resolution stated, however, that full membership would be delayed until Cuba was "in conformity with the practices, purposes, and principles of the OAS".[137] Fidel Castro restated his position that he was not interested in joining after the OAS resolution had been announced.[166]

Effective 14 January 2013, Cuba ended the requirement established in 1961, that any citizens who wish to travel abroad were required to obtain an expensive government permit and a letter of invitation.[167][168][169] In 1961 the Cuban government had imposed broad restrictions on travel to prevent the mass emigration of people after the 1959 revolution;[170] it approved exit visas only on rare occasions.[171] Requirements were simplified: Cubans need only a passport and a national ID card to leave; and they are allowed to take their young children with them for the first time.[172] However, a passport costs on average five months' salary. Observers expect that Cubans with paying relatives abroad are most likely to be able to take advantage of the new policy.[173] In the first year of the program, over 180,000 left Cuba and returned.[174]

As of December 2014, talks with Cuban officials and American officials, including President Barack Obama, resulted in the release of Alan Gross, fifty-two political prisoners, and an unnamed non-citizen agent of the United States in return for the release of three Cuban agents then imprisoned in the United States. Additionally, while the embargo between the United States and Cuba was not immediately lifted, it was relaxed to allow import, export, and certain limited commerce.[175]

Government and politics

The Republic of Cuba is one of the world's last remaining socialist countries following the Marxist–Leninist ideology. The Constitution of 1976, which defined Cuba as a socialist republic, was replaced by the Constitution of 1992, which is "guided by the ideas of José Martí and the political and social ideas of Marx, Engels and Lenin."[5] The constitution describes the Communist Party of Cuba as the "leading force of society and of the state".[5]

The First Secretary of the Communist Party is concurrently President of the Council of State (President of Cuba) and President of the Council of Ministers (sometimes referred to as Prime Minister of Cuba).[176] Members of both councils are elected by the National Assembly of People's Power.[5] The President of Cuba, who is also elected by the Assembly, serves for five years and there is no limit to the number of terms of office.[5]

The People's Supreme Court serves as Cuba's highest judicial branch of government. It is also the court of last resort for all appeals against the decisions of provincial courts.

Cuba's national legislature, the National Assembly of People's Power (Asamblea Nacional de Poder Popular), is the supreme organ of power; 609 members serve five-year terms.[5] The assembly meets twice a year; between sessions legislative power is held by the 31 member Council of Ministers. Candidates for the Assembly are approved by public referendum. All Cuban citizens over 16 who have not been convicted of a criminal offense can vote.[177] Article 131 of the Constitution states that voting shall be "through free, equal and secret vote".[5] Article 136 states: "In order for deputies or delegates to be considered elected they must get more than half the number of valid votes cast in the electoral districts".[5]

No political party is permitted to nominate candidates or campaign on the island, including the Communist Party.[178] The Communist Party of Cuba has held six party congress meetings since 1975. In 2011, the party stated that there were 800,000 members, and representatives generally constitute at least half of the Councils of state and the National Assembly. The remaining positions are filled by candidates nominally without party affiliation. Other political parties campaign and raise finances internationally, while activity within Cuba by opposition groups is minimal.

Cuba is considered an authoritarian regime according to the 2016 Democracy Index[179] and 2017 Freedom in the World survey.[180]

In February 2013, Cuban president Raúl Castro announced he would resign in 2018, ending his five-year term, and that he hopes to implement permanent term limits for future Cuban Presidents, including age limits.[181]

After Fidel Castro died on 25 November 2016, the Cuban government declared a nine-day mourning period. During the mourning period Cuban citizens were prohibited from playing loud music, partying, and drinking alcohol.[182]

Administrative divisions

The country is subdivided into 15 provinces and one special municipality (Isla de la Juventud). These were formerly part of six larger historical provinces: Pinar del Río, Habana, Matanzas, Las Villas, Camagüey and Oriente. The present subdivisions closely resemble those of the Spanish military provinces during the Cuban Wars of Independence, when the most troublesome areas were subdivided. The provinces are divided into municipalities.

Human rights

The Cuban government has been accused of numerous human rights abuses including torture, arbitrary imprisonment, unfair trials, and extrajudicial executions (also known as "El Paredón").[183][184] Human Rights Watch has stated that the government "represses nearly all forms of political dissent" and that "Cubans are systematically denied basic rights to free expression, association, assembly, privacy, movement, and due process of law".[185]

In 2003, the European Union (EU) accused the Cuban government of "continuing flagrant violation of human rights and fundamental freedoms".[186] It has continued to call regularly for social and economic reform in Cuba, along with the unconditional release of all political prisoners.[187] The United States continues an embargo against Cuba "so long as it continues to refuse to move toward democratization and greater respect for human rights",[188] though the UN General Assembly has, since 1992, passed a resolution every year condemning the ongoing impact of the embargo and claiming it violates the Charter of the United Nations and international law.[189] Cuba considers the embargo itself a violation of human rights.[190] On 17 December 2014, United States President Barack Obama announced the re-establishment of diplomatic relations with Cuba, pushing for Congress to put an end to the embargo.[191]

Cuba had the second-highest number of imprisoned journalists of any nation in 2008 (China had the highest) according to various sources, including the Committee to Protect Journalists and Human Rights Watch.[192][193]

Cuban dissidents face arrest and imprisonment. In the 1990s, Human Rights Watch reported that Cuba's extensive prison system, one of the largest in Latin America, consists of 40 maximum-security prisons, 30 minimum-security prisons, and over 200 work camps.[194] According to Human Rights Watch, Cuba's prison population is confined in "substandard and unhealthy conditions, where prisoners face physical and sexual abuse".[194]

In July 2010, the unofficial Cuban Human Rights Commission said there were 167 political prisoners in Cuba, a fall from 201 at the start of the year. The head of the commission stated that long prison sentences were being replaced by harassment and intimidation.[195] During the entire period of Castro's rule over the island, an estimated 200,000 people had been imprisoned or deprived of their freedoms for political reasons.[17]

Foreign relations

Cuba has conducted a foreign policy that is uncharacteristic of such a minor, developing country.[196][197] Under Castro, Cuba was heavily involved in wars in Africa, Central America and Asia. Cuba supported Algeria in 1961–1965,[198] and sent tens of thousands of troops to Angola during the Angolan Civil War.[199] Other countries that featured Cuban involvement include Ethiopia,[200][201] Guinea,[202] Guinea-Bissau,[203] Mozambique,[204] and Yemen.[205] Lesser known actions include the 1959 expedition to the Dominican Republic.[206] The expedition failed, but a prominent monument to its members was erected in their memory in Santo Domingo by the Dominican government, and they feature prominently at the country's Memorial Museum of the Resistance.[207]

In 2008, the European Union (EU) and Cuba agreed to resume full relations and cooperation activities.[208] Cuba is a founding member of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas.[209] At the end of 2012, tens of thousands of Cuban medical personnel worked abroad,[210] with as many as 30,000 doctors in Venezuela alone via the two countries' oil-for-doctors programme.[211]

In 1996, the United States, then under President Bill Clinton, brought in the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act, better known as the Helms–Burton Act.[212] In 2009, United States President Barack Obama stated on 17 April, in Trinidad and Tobago that "the United States seeks a new beginning with Cuba",[213] and reversed the Bush Administration's prohibition on travel and remittances by Cuban-Americans from the United States to Cuba.[214] Five years later, an agreement between the United States and Cuba, popularly called "The Cuban Thaw", brokered in part by Canada and Pope Francis, began the process of restoring international relations between the two countries. They agreed to release political prisoners and the United States began the process of creating an embassy in Havana.[215][216][217][218][219] This was realized on 30 June 2015, when Cuba and the U.S. reached a deal to reopen embassies in their respective capitals on 20 July 2015[220] and reestablish diplomatic relations.[221] Earlier in the same year, the White House announced that President Obama would remove Cuba from the American government's list of nations that sponsor terrorism,[222][223] which Cuba reportedly welcomed as "fair".[224] On 17 September 2017, the United States considered closing its Cuban embassy following mysterious sonic attacks on its staff.[225]

Crime and law enforcement

All law enforcement agencies are maintained under Cuba's Ministry of the Interior, which is supervised by the Revolutionary Armed Forces. In Cuba, citizens can receive police assistance by dialing 106 on their telephones.[226] The police force, which is referred to as "Policía Nacional Revolucionaria" or PNR, is then expected to provide help. The Cuban government also has an agency called the Intelligence Directorate that conducts intelligence operations and maintains close ties with the Russian Federal Security Service.

Military

As of 2009, Cuba spent about US$91.8 million on its armed forces.[227] In 1985, Cuba devoted more than 10% of its GDP to military expenditures.[228] In response to perceived American aggression, such as the Bay of Pigs Invasion, Cuba built up one of the largest armed forces in Latin America, second only to that of Brazil.[229]

From 1975 until the late 1980s, Soviet military assistance enabled Cuba to upgrade its military capabilities. After the loss of Soviet subsidies, Cuba scaled down the numbers of military personnel, from 235,000 in 1994 to about 60,000 in 2003.[230]

In 2017, Cuba signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[231]

Economy

The Cuban state claims to adhere to socialist principles in organizing its largely state-controlled planned economy. Most of the means of production are owned and run by the government and most of the labor force is employed by the state. Recent years have seen a trend toward more private sector employment. By 2006, public sector employment was 78% and private sector 22%, compared to 91.8% to 8.2% in 1981.[232] Government spending is 78.1% of GDP.[233] Any firm that hires a Cuban must pay the Cuban government, which in turn pays the employee in Cuban pesos.[234] The average monthly wage as of July 2013 is 466 Cuban pesos—about US$19.[235]

Cuba has a dual currency system, whereby most wages and prices are set in Cuban pesos (CUP), while the tourist economy operates with Convertible pesos (CUC), set at par with the US dollar.[235] Every Cuban household has a ration book (known as libreta) entitling it to a monthly supply of food and other staples, which are provided at nominal cost.[236]

Before Fidel Castro's 1959 revolution, Cuba was one of the most advanced and successful countries in Latin America.[237] Cuba's capital, Havana, was a "glittering and dynamic city".[237] The country's economy in the early part of the century, fuelled by the sale of sugar to the United States, had grown wealthy. Cuba ranked 5th in the hemisphere in per capita income, 3rd in life expectancy, 2nd in per capita ownership of automobiles and telephones, and 1st in the number of television sets per inhabitant. Cuba's literacy rate, 76%, was the fourth highest in Latin America. Cuba also ranked 11th in the world in the number of doctors per capita. Several private clinics and hospitals provided services for the poor. Cuba's income distribution compared favorably with that of other Latin American societies. However, income inequality was profound between city and countryside, especially between whites and blacks. Cubans lived in abysmal poverty in the countryside. According to PBS, a thriving middle class held the promise of prosperity and social mobility.[237] According to Cuba historian Louis Perez of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, "Havana was then what Las Vegas has become."[238] In 2016, the Miami Herald wrote, "... about 27 percent of Cubans earn under $50 per month; 34 percent earn the equivalent of $50 to $100 per month; and 20 percent earn $101 to $200. Twelve percent reported earning $201 to $500 a month; and almost 4 percent said their monthly earnings topped $500, including 1.5 percent who said they earned more than $1,000."[239]

After the Cuban revolution and before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba depended on Moscow for substantial aid and sheltered markets for its exports. The loss of these subsidies sent the Cuban economy into a rapid depression known in Cuba as the Special Period. Cuba took limited free market-oriented measures to alleviate severe shortages of food, consumer goods, and services. These steps included allowing some self-employment in certain retail and light manufacturing sectors, the legalization of the use of the US dollar in business, and the encouragement of tourism. Cuba has developed a unique urban farm system called organopónicos to compensate for the end of food imports from the Soviet Union. The U.S. embargo against Cuba was instituted in response to nationalization of U.S.-citizen-held property and was maintained at the premise of perceived human rights violations. It is widely viewed that the embargo hurt the Cuban economy. In 2009, the Cuban Government estimated this loss at $685 million annually.[240]

Cuba's leadership has called for reforms in the country's agricultural system. In 2008, Raúl Castro began enacting agrarian reforms to boost food production, as at that time 80% of food was imported. The reforms aim to expand land use and increase efficiency.[241] Venezuela supplies Cuba with an estimated 110,000 barrels (17,000 m3) of oil per day in exchange for money and the services of some 44,000 Cubans, most of them medical personnel, in Venezuela.[242][243]

In 2005, Cuba had exports of US$2.4 billion, ranking 114 of 226 world countries, and imports of US$6.9 billion, ranking 87 of 226 countries.[244] Its major export partners are Canada 17.7%, China 16.9%, Venezuela 12.5%, Netherlands 9%, and Spain 5.9% (2012).[245] Cuba's major exports are sugar, nickel, tobacco, fish, medical products, citrus fruits, and coffee;[245] imports include food, fuel, clothing, and machinery. Cuba presently holds debt in an amount estimated at $13 billion,[246] approximately 38% of GDP.[247] According to the Heritage Foundation, Cuba is dependent on credit accounts that rotate from country to country.[248] Cuba's prior 35% supply of the world's export market for sugar has declined to 10% due to a variety of factors, including a global sugar commodity price drop that made Cuba less competitive on world markets.[249] It was announced in 2008 that wage caps would be abandoned to improve the nation's productivity.[250]

In 2010, Cubans were allowed to build their own houses. According to Raúl Castro, they could now improve their houses, but the government would not endorse these new houses or improvements.[251] There is virtually no homelessness in Cuba, and 85% of Cubans own their homes and pay no property taxes or mortgage interest. Mortgage payments may not exceed 10% of a household's combined income..

On 2 August 2011, The New York Times reported that Cuba reaffirmed its intent to legalize "buying and selling" of private property before the year's end. According to experts, the private sale of property could "transform Cuba more than any of the economic reforms announced by President Raúl Castro's government".[252] It would cut more than one million state jobs, including party bureaucrats who resist the changes.[253] The reforms created what some call "New Cuban Economy".[254][255] In October 2013, Raúl said he intended to merge the two currencies, but as of August 2016, the dual currency system remains in force.

In August 2012, a specialist of the "Cubaenergia Company" announced the opening of Cuba's first Solar Power Plant. As a member of the Cubasolar Group, there was also a mention of ten additional plants in 2013.[256]

In May 2019, Cuba imposed rationing of staples such as chicken, eggs, rice, beans, soap and other basics. (Some two-thirds of food in the country is imported.) A spokesperson blamed the increased U.S. trade embargo although economists believe that an equally important problem is the massive decline of aid from Venezuela and the failure of Cuba's state-run oil company which had subsidized fuel costs.[257]

Resources

Cuba's natural resources include sugar, tobacco, fish, citrus fruits, coffee, beans, rice, potatoes, and livestock. Cuba's most important mineral resource is nickel, with 21% of total exports in 2011.[258] The output of Cuba's nickel mines that year was 71,000 tons, approaching 4% of world production.[259] As of 2013 its reserves were estimated at 5.5 million tons, over 7% of the world total.[259] Sherritt International of Canada operates a large nickel mining facility in Moa. Cuba is also a major producer of refined cobalt, a by-product of nickel mining.[260]

Oil exploration in 2005 by the US Geological Survey revealed that the North Cuba Basin could produce about 4.6 billion barrels (730,000,000 m3) to 9.3 billion barrels (1.48×109 m3) of oil. In 2006, Cuba started to test-drill these locations for possible exploitation.[261]

Tourism

.jpg)

Tourism was initially restricted to enclave resorts where tourists would be segregated from Cuban society, referred to as "enclave tourism" and "tourism apartheid".[262] Contact between foreign visitors and ordinary Cubans was de facto illegal between 1992 and 1997.[263] The rapid growth of tourism during the Special Period had widespread social and economic repercussions in Cuba, and led to speculation about the emergence of a two-tier economy.[264]

Cuba has tripled its market share of Caribbean tourism in the last decade; as a result of significant investment in tourism infrastructure, this growth rate is predicted to continue.[265] 1.9 million tourists visited Cuba in 2003, predominantly from Canada and the European Union, generating revenue of US$2.1 billion.[266] Cuba recorded 2,688,000 international tourists in 2011, the third-highest figure in the Caribbean (behind the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico).[267]

The medical tourism sector caters to thousands of European, Latin American, Canadian, and American consumers every year.

A recent study indicates that Cuba has a potential for mountaineering activity, and that mountaineering could be a key contributor to tourism, along with other activities, e.g. biking, diving, caving. Promoting these resources could contribute to regional development, prosperity, and well-being.[268]

The Cuban Justice minister downplays allegations of widespread sex tourism.[269] According to a Government of Canada travel advice website, "Cuba is actively working to prevent child sex tourism, and a number of tourists, including Canadians, have been convicted of offences related to the corruption of minors aged 16 and under. Prison sentences range from 7 to 25 years."[270]

Some tourist facilities were extensively damaged on 8 September 2017 when Hurricane Irma hit the island. The storm made landfall in the Camagüey Archipelago; the worst damage was in the keys north of the main island, however, and not in the most significant tourist areas.[271]

Geography

Cuba is an archipelago of islands located in the northern Caribbean Sea at the confluence with the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. It lies between latitudes 19° and 24°N, and longitudes 74° and 85°W. The United States lies 150 kilometers (93 miles) across the Straits of Florida to the north and northwest (to the closest tip of Key West, Florida), and the Bahamas 21 km (13 mi) to the north. Mexico lies 210 kilometers (130 miles) across the Yucatán Channel to the west (to the closest tip of Cabo Catoche in the State of Quintana Roo).

Haiti is 77 km (48 mi) to the east, Jamaica (140 km/87 mi) and the Cayman Islands to the south. Cuba is the principal island, surrounded by four smaller groups of islands: the Colorados Archipelago on the northwestern coast, the Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago on the north-central Atlantic coast, the Jardines de la Reina on the south-central coast and the Canarreos Archipelago on the southwestern coast.

The main island, named Cuba, is 1,250 km (780 mi) long, constituting most of the nation's land area (104,556 km2 (40,369 sq mi)) and is the largest island in the Caribbean and 17th-largest island in the world by land area. The main island consists mostly of flat to rolling plains apart from the Sierra Maestra mountains in the southeast, whose highest point is Pico Turquino (1,974 m (6,476 ft)).

The second-largest island is Isla de la Juventud (Isle of Youth) in the Canarreos archipelago, with an area of 2,200 km2 (849 sq mi). Cuba has an official area (land area) of 109,884 km2 (42,426 sq mi). Its area is 110,860 km2 (42,803 sq mi) including coastal and territorial waters.

Climate

With the entire island south of the Tropic of Cancer, the local climate is tropical, moderated by northeasterly trade winds that blow year-round. The temperature is also shaped by the Caribbean current, which brings in warm water from the equator. This makes the climate of Cuba warmer than that of Hong Kong, which is at around the same latitude as Cuba but has a subtropical rather than a tropical climate. In general (with local variations), there is a drier season from November to April, and a rainier season from May to October. The average temperature is 21 °C (69.8 °F) in January and 27 °C (80.6 °F) in July. The warm temperatures of the Caribbean Sea and the fact that Cuba sits across the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico combine to make the country prone to frequent hurricanes. These are most common in September and October.

Hurricane Irma hit the island on 8 September 2017, with winds of 260 kilometres per hour,[272] at the Camagüey Archipelago; the storm reached Ciego de Avila province around midnight and continued to pound Cuba the next day.[273] The worst damage was in the keys north of the main island. Hospitals, warehouses and factories were damaged; much of the north coast was without electricity. By that time, nearly a million people, including tourists, had been evacuated.[271] The Varadero resort area also reported widespread damage; the government believed that repairs could be completed before the start of the main tourist season.[274] Subsequent reports indicated that ten people had been killed during the storm, including seven in Havana, most during building collapses. Sections of the capital had been flooded.[274] Hurricane Jose was not expected to strike Cuba.[275]

Biodiversity

Cuba signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 12 June 1992, and became a party to the convention on 8 March 1994.[276] It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, with one revision, that the convention received on 24 January 2008.[277]

The revision consists of an action plan with time limits for each item, and an indication of the governmental body responsible for delivery. That document contains virtually no information about biodiversity. However, the country's fourth national report to the CBD contains a detailed breakdown of the numbers of species of each kingdom of life recorded from Cuba, the main groups being: animals (17,801 species), bacteria (270), chromista (707), fungi, including lichen-forming species (5844), plants (9107) and protozoa (1440).[278]

As elsewhere in the world, vertebrate animals and flowering plants are well documented, so the recorded numbers of species are probably close to the true numbers. For most or all other groups, the true numbers of species occurring in Cuba are likely to exceed, often considerably, the numbers recorded so far.

The flora of Cuba lists species like the Pinus cubensis, Begonia cubensis, royal palm, Copernicia humicola and Coccothrinax yunquensis. Orchis include species like Bletia florida, several species of Brassavola; Brassavola caudata and Brassavola maculata. A Melocactus; Melocactus matanzanus is an endemic species of cactus.

The fauna of Cuba lists species like the Prehensile-tailed hutia, Cuban crocodile, Cuban solenodon, Cuban amazon and Cuban emerald. Cuba also formerly hosted a radiation of sloths belonging to the family Megalocnidae including Megalocnus, Acratocnus, Parocnus and Neocnus, as well as the monkey Paralouatta as well as several species of Nesophontes.

Cuban moist forests(21,400 km), Cuban pine forests(6400 km), and Cuban dry forests(65,800 km) cover about a third of Cuba

Demographics

| Population[280][281] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 5.9 | ||

| 2000 | 11.1 | ||

| 2018 | 11.3 | ||

According to the official census of 2010, Cuba's population was 11,241,161, comprising 5,628,996 men and 5,612,165 women.[282] Its birth rate (9.88 births per thousand population in 2006)[283] is one of the lowest in the Western Hemisphere. Although the country's population has grown by about four million people since 1961, the rate of growth slowed during that period, and the population began to decline in 2006, due to the country's low fertility rate (1.43 children per woman) coupled with emigration.[284]

Indeed, this drop in fertility is among the largest in the Western Hemisphere[285] and is attributed largely to unrestricted access to legal abortion: Cuba's abortion rate was 58.6 per 1000 pregnancies in 1996, compared to an average of 35 in the Caribbean, 27 in Latin America overall, and 48 in Europe. Similarly, the use of contraceptives is also widespread, estimated at 79% of the female population (in the upper third of countries in the Western Hemisphere).[286]

Ethnoracial groups

Cuba's population is multiethnic, reflecting its complex colonial origins. Intermarriage between diverse groups is widespread, and consequently there is some discrepancy in reports of the country's racial composition: whereas the Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies at the University of Miami determined that 62% of Cubans are black,[287] the 2002 Cuban census found that a similar proportion of the population, 65.05%, was white.

In fact, the Minority Rights Group International determined that "An objective assessment of the situation of Afro-Cubans remains problematic due to scant records and a paucity of systematic studies both pre- and post-revolution. Estimates of the percentage of people of African descent in the Cuban population vary enormously, ranging from 34% to 62%".[288]

A 2014 study found that, based on ancestry informative markers (AIM), autosomal genetic ancestry in Cuba is 72% European, 20% African, and 8% Indigenous.[289] Around 35% of maternal lineages derive from Cuban Indigenous People, compared to 39% from Africa and 26% from Europe, but male lineages were European (82%) and African (18%), indicating a historical bias towards mating between foreign men and native women rather than the inverse.[289]

Asians make up about 1% of the population, and are largely of Chinese ancestry, followed by Japanese.[290][291] Many are descendants of farm laborers brought to the island by Spanish and American contractors during the 19th and early 20th century.[292] The current recorded number of Cubans with Chinese ancestry is 114,240.[293]

Ancestral contributions in Cubans as inferred from autosomal AIMs.

Ancestral contributions in Cubans as inferred from autosomal AIMs. Ancestral contributions in Cubans as inferred from Y-chromosome markers.

Ancestral contributions in Cubans as inferred from Y-chromosome markers. Ancestral contributions in Cubans as inferred from mtDNA markers.

Ancestral contributions in Cubans as inferred from mtDNA markers.

Afro-Cubans are descended primarily from the Yoruba people, Bantu people from the Congo basin, Kalabari tribe and Arará from the Dahomey[294] as well as several thousand North African refugees, most notably the Sahrawi Arabs of Western Sahara.[295]

Migration

Immigration

Immigration and emigration have played a prominent part in Cuba's demographic profile. Between the 18th and early 20th century, large waves of Canarian, Catalan, Andalusian, Galician, and other Spanish people immigrated to Cuba. Between 1899–1930 alone, close to a million Spaniards entered the country, though many would eventually return to Spain.[296] Other prominent immigrant groups included French,[297] Portuguese, Italian, Russian, Dutch, Greek, British, and Irish, as well as small number of descendants of U.S. citizens who arrived in Cuba in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Emigration

Post-revolution Cuba has been characterized by significant levels of emigration, which has led to a large and influential diaspora community. During the three decades after January 1959, more than one million Cubans of all social classes — constituting 10% of the total population — emigrated to the United States, a proportion that matches the extent of emigration to the U.S. from the Caribbean as a whole during that period.[298][299][300][301][302] Prior to 13 January 2013, Cuban citizens could not travel abroad, leave or return to Cuba without first obtaining official permission along with applying for a government issued passport and travel visa, which was often denied.[303] Those who left the country typically did so by sea, in small boats and fragile rafts. On 9 September 1994, the U.S. and Cuban governments agreed that the U.S. would grant at least 20,000 visas annually in exchange for Cuba's pledge to prevent further unlawful departures on boats.[304] As of 2013 the top emigration destinations were the United States, Spain, Italy, Puerto Rico, and Mexico.[305]

Religion

In 2010, the Pew Forum estimated that religious affiliation in Cuba is 65% Christian (60% Roman Catholic or about 6.9 million in 2016, 5% Protestant or about 575,000 in 2016), 23% unaffiliated, 17% folk religion (such as santería), and the remaining 0.4% consisting of other religions.[306]

Cuba is officially a secular state. Religious freedom increased through the 1980s,[307] with the government amending the constitution in 1992 to drop the state's characterization as atheistic.[308]

Roman Catholicism is the largest religion, with its origins in Spanish colonization. Despite less than half of the population identifying as Catholics in 2006, it nonetheless remains the dominant faith.[248] Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI visited Cuba in 1998 and 2011, respectively, and Pope Francis visited Cuba in September 2015.[309][310] Prior to each papal visit, the Cuban government pardoned prisoners as a humanitarian gesture.[311][312]

The government's relaxation of restrictions on house churches in the 1990s led to an explosion of Pentecostalism, with some groups claiming as many as 100,000 members. However, Evangelical Protestant denominations, organized into the umbrella Cuban Council of Churches, remain much more vibrant and powerful.[313]

The religious landscape of Cuba is also strongly defined by syncretisms of various kinds. Christianity is often practiced in tandem with Santería, a mixture of Catholicism and mostly African faiths, which include a number of cults. La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre (the Virgin of Cobre) is the Catholic patroness of Cuba, and a symbol of Cuban culture. In Santería, she has been syncretized with the goddess Oshun.

Cuba also hosts small communities of Jews (500 in 2012), Muslims, and members of the Bahá'í Faith.[314]

Several well-known Cuban religious figures have operated outside the island, including the humanitarian and author Jorge Armando Pérez.

Languages

The official language of Cuba is Spanish and the vast majority of Cubans speak it. Spanish as spoken in Cuba is known as Cuban Spanish and is a form of Caribbean Spanish. Lucumí, a dialect of the West African language Yoruba, is also used as a liturgical language by practitioners of Santería,[315] and so only as a second language.[316] Haitian Creole is the second most spoken language in Cuba, and is spoken by Haitian immigrants and their descendants.[317] Other languages spoken by immigrants include Galician and Corsican.[318]

Largest cities

Media

The Cuban government and Communist Party of Cuba control almost all media in Cuba.

Television

Five government-controlled national channels:

- Cubavisión

- Tele Rebelde

- Canal Educativo

- Canal Educativo 2

- Multivisión

Internet

Internet in Cuba has some of the lowest penetration rates in the Western hemisphere, and all content is subject to review by the Department of Revolutionary Orientation.[320] ETECSA operates 118 cybercafes in the country.[320] The government of Cuba provides an online encyclopedia website called EcuRed that operates in a "wiki" format.[321] Internet access was limited,[322] and the sale of computer equipment was strictly regulated.

In 2015, the Cuban government opened the first public wi-fi hotspots in 35 public locations. By January 2018, there were public hotspots in approximately 500 public locations nationwide providing access in most major cities, and the sight of Cubans gathered in this locations became widely mentioned. In December 2018, Etecsa began offering mobile nternet, initially only 3G, but with some 4G coverage beginning during 2019.

Culture

Cuban culture is influenced by its melting pot of cultures, primarily those of Spain and Africa. After the 1959 revolution, the government started a national literacy campaign, offered free education to all and established rigorous sports, ballet, and music programs.[323]

Music

Cuban music is very rich and is the most commonly known expression of Cuban culture. The central form of this music is son, which has been the basis of many other musical styles like "Danzón de nuevo ritmo", mambo, cha-cha-chá and salsa music. Rumba ("de cajón o de solar") music originated in the early Afro-Cuban culture, mixed with Hispanic elements of style.[324] The Tres was invented in Cuba from Hispanic cordophone instruments models (the instrument is actually a fusion of elements from the Spanish guitar and lute). Other traditional Cuban instruments are of African origin, Taíno origin, or both, such as the maracas, güiro, marímbula and various wooden drums including the mayohuacán.

Popular Cuban music of all styles has been enjoyed and praised widely across the world. Cuban classical music, which includes music with strong African and European influences, and features symphonic works as well as music for soloists, has received international acclaim thanks to composers like Ernesto Lecuona. Havana was the heart of the rap scene in Cuba when it began in the 1990s.

During that time, reggaetón grew in popularity. In 2011, the Cuban state denounced reggaeton as degenerate, directed reduced "low-profile" airplay of the genre (but did not ban it entirely) and banned the megahit Chupi Chupi by Osmani García, characterizing its description of sex as "the sort which a prostitute would carry out."[325] In December 2012, the Cuban government officially banned sexually explicit reggaeton songs and music videos from radio and television.[326][327] As well as pop, classical and rock are very popular in Cuba.

Cuisine

_Tamales_pli%C3%A9s.jpg)

Cuban cuisine is a fusion of Spanish and Caribbean cuisines. Cuban recipes share spices and techniques with Spanish cooking, with some Caribbean influence in spice and flavor. Food rationing, which has been the norm in Cuba for the last four decades, restricts the common availability of these dishes.[328] The traditional Cuban meal is not served in courses; all food items are served at the same time.

The typical meal could consist of plantains, black beans and rice, ropa vieja (shredded beef), Cuban bread, pork with onions, and tropical fruits. Black beans and rice, referred to as moros y cristianos (or moros for short), and plantains are staples of the Cuban diet. Many of the meat dishes are cooked slowly with light sauces. Garlic, cumin, oregano, and bay leaves are the dominant spices.

Literature

Cuban literature began to find its voice in the early 19th century. Dominant themes of independence and freedom were exemplified by José Martí, who led the Modernist movement in Cuban literature. Writers such as Nicolás Guillén and José Z. Tallet focused on literature as social protest. The poetry and novels of Dulce María Loynaz and José Lezama Lima have been influential. Romanticist Miguel Barnet, who wrote Everyone Dreamed of Cuba, reflects a more melancholy Cuba.[329]

Alejo Carpentier was important in the Magic realism movement. Writers such as Reinaldo Arenas, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and more recently Daína Chaviano, Pedro Juan Gutiérrez, Zoé Valdés, Guillermo Rosales and Leonardo Padura have earned international recognition in the post-revolutionary era, though many of these writers have felt compelled to continue their work in exile due to ideological control of media by the Cuban authorities.

Dance

Dance holds a privileged position in Cuban culture. Popular dance is considered an essential part of life, and concert dance is supported by the government and includes internationally renowned companies such as the Ballet Nacional de Cuba.[330]

Sports

Due to historical associations with the United States, many Cubans participate in sports that are popular in North America, rather than sports traditionally played in other Latin American nations. Baseball is the most popular. Other sports and pastimes include football, basketball, volleyball, cricket, and athletics. Cuba is a dominant force in amateur boxing, consistently achieving high medal tallies in major international competitions. Cuban boxers are not permitted to turn professional by their government. However, many boxers defect to the U.S. and other countries.[331][332] Cuba also provides a national team that competes in the Olympic Games.[333]

Education

The University of Havana was founded in 1728 and there are a number of other well-established colleges and universities. In 1957, just before Castro came to power, the literacy rate was fourth in the region at almost 80% according to the United Nations, higher than in Spain.[112][334] Castro created an entirely state-operated system and banned private institutions. School attendance is compulsory from ages six to the end of basic secondary education (normally at age 15), and all students, regardless of age or gender, wear school uniforms with the color denoting grade level. Primary education lasts for six years, secondary education is divided into basic and pre-university education.[335] Cuba's literacy rate of 99.8 percent[245][336] is the tenth-highest globally, due largely to the provision of free education at every level.[337] Cuba's high school graduation rate is 94 percent.[338]

Higher education is provided by universities, higher institutes, higher pedagogical institutes, and higher polytechnic institutes. The Cuban Ministry of Higher Education operates a distance education program that provides regular afternoon and evening courses in rural areas for agricultural workers. Education has a strong political and ideological emphasis, and students progressing to higher education are expected to have a commitment to the goals of Cuba.[335] Cuba has provided state subsidized education to a limited number of foreign nationals at the Latin American School of Medicine.[339][340]

According to the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities, the top-ranking universities in the country are Universidad de la Habana (1680th worldwide), Instituto Superior Politécnico José Antonio Echeverría (2893rd) and the University of Santiago de Cuba (3831st).[341]

Health

Cuba's life expectancy at birth is 79.2 years (76.8 for males and 81.7 for females). This ranks Cuba 59th in the world and 5th in the Americas, behind Canada, Chile, Costa Rica and the United States.[342] Infant mortality declined from 32 infant deaths per 1,000 live births in 1957, to 10 in 1990–95,[343] 6.1 in 2000–2005 and 5.13 in 2009.[336][245] Historically, Cuba has ranked high in numbers of medical personnel and has made significant contributions to world health since the 19th century.[112] Today, Cuba has universal health care and despite persistent shortages of medical supplies, there is no shortage of medical personnel.[344] Primary care is available throughout the island and infant and maternal mortality rates compare favorably with those in developed nations.[344] That a developing nation like Cuba has health outcomes rivaling the developed world is referred to by researchers as the Cuban Health Paradox.[345] Cuba ranks 30th on the 2019 Bloomberg Healthiest Country Index, which is the only developing country to rank that high.[346]