Havana

The Havana (/həˈvænə/; Spanish: La Habana [la aˈβana] (![]()

Havana La Habana | |

|---|---|

From upper left: Havana Cathedral, Plaza Vieja, view of Old Havana, Great Theatre of Havana, and the San Francisco Square | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): City of Columns[1] | |

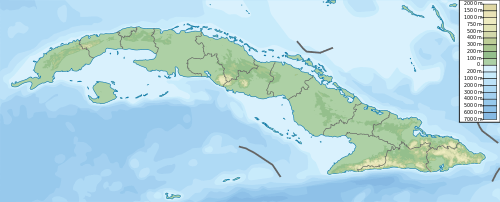

Havana Location in Cuba  Havana Havana (Caribbean)  Havana Havana (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 23°08′12″N 82°21′32″W | |

| Country | |

| Province | La Habana |

| Established | 1519 |

| Municipalities | 15 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Gobierno Provincial de La Habana |

| • Governor | Reinaldo García Zapata (PCC) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 728.26 km2 (281.18 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 59 m (194 ft) |

| Population 12-31-2018[2] | |

| • Total | 2,131,480 |

| • Density | 2,892.0/km2 (7,490/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Habanero/a |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (UTC−05:00) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (UTC−04:00) |

| Postal code | 10xxx–19xxx |

| Area code(s) | (+53) 07 |

| Patron saints | Saint Christopher |

| HDI (2018) | 0.804[3] – very high |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Old Havana and its Fortification System |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv, v |

| Designated | 1982 (6th session) |

| Reference no. | 204 |

| State Party | Cuba |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

The city of Havana was founded by the Spanish in the 16th century and due to its strategic location it served as a springboard for the Spanish conquest of the Americas, becoming a stopping point for treasure-laden Spanish galleons returning to Spain. The King Philip II of Spain granted Havana the title of City in 1592.[7] Walls as well as forts were built to protect the old city.[8] The sinking of the U.S. battleship Maine in Havana's harbor in 1898 was the immediate cause of the Spanish–American War.[9]

The city is the center of the Cuban government, and home to various ministries, headquarters of businesses and over 100 diplomatic offices.[10] The governor is Reinaldo García Zapata of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC).[11][12] In 2009, the city/province had the third highest income in the country.[13]

Contemporary Havana can essentially be described as three cities in one: Old Havana, Vedado and the newer suburban districts. The city extends mostly westward and southward from the bay, which is entered through a narrow inlet and which divides into three main harbors: Mari melena, Guanabacoa and Antares. The sluggish Almendares River traverses the city from south to north, entering the Straits of Florida a few miles west of the bay.[14]

The city attracts over a million tourists annually;[15] the Official Census for Havana reports that in 2010 the city was visited by 1,176,627 international tourists,[15] a 20% increase from 2005. Old Havana was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982.[16] The city is also noted for its history, culture, architecture and monuments.[17] As typical of Cuba, Havana experiences a tropical climate.[18]

Etymology

Most native settlements became the site of Spanish colonial cities retaining their original Taíno names.

History

Colonial period

16th century

Conquistador Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar founded Havana on August 25, 1515, on the southern coast of the island, near the present town of Surgidero de Batabanó, or more likely on the banks of the Mayabeque River close to Playa Mayabeque. All attempts to found a city on Cuba's south coast failed. However, an early map of Cuba drawn in 1514 places the town at the mouth of this river.[19][20]

Between 1514 and 1519 the Spanish established at least two settlements on the north coast, one of them in La Chorrera, today in the neighborhoods of Vedado and Miramar, next to the Almendares River. The town that became Havana finally originated adjacent to what was then called Puerto de Carenas (literally, "Careening Bay"), in 1519. The quality of this natural bay, which now hosts Havana's harbor, warranted this change of location.

Pánfilo de Narváez gave Havana – the sixth town founded by the Spanish on Cuba – its name: San Cristóbal de la Habana. The name combines San Cristóbal, patron saint of Havana. Shortly after the founding of Cuba's first cities, the island served as little more than a base for the Conquista of other lands.

Havana began as a trading port, and suffered regular attacks by buccaneers, pirates, and French corsairs. The first attack and resultant burning of the city was by the French corsair Jacques de Sores in 1555. Such attacks convinced the Spanish Crown to fund the construction of the first fortresses in the main cities – not only to counteract the pirates and corsairs, but also to exert more control over commerce with the West Indies, and to limit the extensive contrabando (black market) that had arisen due to the trade restrictions imposed by the Casa de Contratación of Seville (the crown-controlled trading house that held a monopoly on New World trade).

Ships from all over the New World carried products first to Havana, in order to be taken by the fleet to Spain. The thousands of ships gathered in the city's bay also fueled Havana's agriculture and manufacture, since they had to be supplied with food, water, and other products needed to traverse the ocean.

On December 20, 1592, King Philip II of Spain granted Havana the title of City. Later on, the city would be officially designated as "Key to the New World and Rampart of the West Indies" by the Spanish Crown. In the meantime, efforts to build or improve the defensive infrastructures of the city continued.

17th century

.jpg)

Havana expanded greatly in the 17th century. New buildings were constructed from the most abundant materials of the island, mainly wood, combining various Iberian architectural styles, as well as borrowing profusely from Canarian characteristics.

In 1649, an epidemic of the often fatal Yellow fever brought from Cartagena in Colombia affected a third of the European population of Havana.[21]

18th century

By the middle of the 18th century Havana had more than seventy thousand inhabitants, and was the third-largest city in the Americas, ranking behind Lima and Mexico City but ahead of Boston and New York.[22] During the 18th century Havana was the most important of the Spanish ports because it had facilities where ships could be refitted and, by 1740, it had become Spain's largest and most active shipyard and only drydock in the New World.[23]

The city was captured by the British during the Seven Years' War. The episode began on June 6, 1762, when at dawn, a British fleet, comprising more than 50 ships and a combined force of over 11,000 men of the Royal Navy and Army, sailed into Cuban waters and made an amphibious landing east of Havana.[24] The British immediately opened up trade with their North American and Caribbean colonies, causing a rapid transformation of Cuban society. Less than a year after Havana was seized, the Peace of Paris was signed by the three warring powers thus ending the Seven Years' War. The treaty gave Britain Florida in exchange for the return of the city of Havana on to Spain.[25]

After regaining the city, the Spanish transformed Havana into the most heavily fortified city in the Americas. Construction began on what was to become the Fortress of San Carlos de la Cabaña, the third biggest Spanish fortification in the New World after Castillo San Cristóbal (the biggest) and Castillo San Felipe del Morro both in San Juan, Puerto Rico. On January 15, 1796, the remains of Christopher Columbus were transported to the island from Santo Domingo. They rested here until 1898, when they were transferred to Seville's Cathedral, after Spain's loss of Cuba.

19th century

As trade between Caribbean and North American states increased in the early 19th century, Havana became a flourishing and fashionable city. Havana's theaters featured the most distinguished actors of the age, and prosperity among the burgeoning middle-class led to expensive new classical mansions being erected. During this period Havana became known as the Paris of the Antilles.

In 1837, the first railroad was constructed, a 51 km (32 mi) stretch between Havana and Bejucal, which was used for transporting sugar from the valley of Güines to the harbor. With this, Cuba became the fifth country in the world to have a railroad, and the first Spanish-speaking country. Throughout the century, Havana was enriched by the construction of additional cultural facilities, such as the Tacon Teatre, one of the most luxurious in the world. The fact that slavery was legal in Cuba until 1886 led to Southern American interest, including a plan by the Knights of the Golden Circle to create a 'Golden Circle' with a 1200 mile-radius centered on Havana. After the Confederate States of America were defeated in the American Civil War in 1865, many former slaveholders continued to run plantations by moving to Havana.

In 1863, the city walls were knocked down so that the metropolis could be enlarged. At the end of the 19th century, Havana witnessed the final moments of Spanish colonialism in the Americas.

Republican period and post-revolution

The 20th century began with Cuba, and therefore Havana, under occupation by the United States.[26] The US occupation officially ended when Tomás Estrada Palma, first president of Cuba, took office on 20 May 1902.

During the Republican Period, from 1902 to 1959, the city saw a new era of development. Cuba recovered from the devastation of war to become a well-off country, with the third largest middle class in the hemisphere. Apartment buildings to accommodate the new middle class, as well as mansions for the Cuban tycoons, were built at a fast pace.

Numerous luxury hotels, casinos and nightclubs were constructed during the 1930s to serve Havana's burgeoning tourist industry, which greatly benefited by the U.S. prohibition on alcohol from 1920 to 1933. In the 1930s, organized crime characters were aware of Havana's nightclub and casino life, and they made their inroads in the city. Santo Trafficante Jr. took the roulette wheel at the Sans Souci Casino, Meyer Lansky directed the Hotel Habana Riviera, with Lucky Luciano at the Hotel Nacional Casino. At the time, Havana became an exotic capital of appeal and numerous activities ranging from marinas, grand prix car racing, musical shows, and parks. It was also the favorite destination of sex tourists.[27]:127

Havana achieved the title of being the Latin American city with the biggest middle class population per-capita, simultaneously accompanied by gambling and corruption where gangsters and stars were known to mix socially. During this era, Havana was generally producing more revenue than Las Vegas, Nevada, whose boom as a tourist destination began only after Havana's casinos closed in 1959. In 1958, about 300,000 American tourists visited the city.

After the revolution of 1959, the new régime under Fidel Castro promised to improve social services, public housing, and official buildings. Nevertheless, after Castro's abrupt expropriation of all private property and industry (May 1959 onwards) under a strong communist model backed by the Soviet Union followed by the U.S. embargo, shortages that affected Cuba in general hit Havana especially hard. By 1966–68, the Cuban government had nationalized all privately owned business entities in Cuba, down to "certain kinds of small retail forms of commerce" (law No. 1076[28]).

A severe economic downturn occurred after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Soviet subsidies ended, representing billions of dollars which the Soviet Union had given the Cuban government. Many believed the revolutionary government would soon collapse, as happened to the Soviet satellite states of Eastern Europe. However, contrary to events in Europe, Cuba's communist government persevered through the 1990s and persists to this day.

After many years of prohibition, the communist government increasingly turned to tourism for new financial revenue, and has allowed foreign investors to build new hotels and develop the hospitality industry. In Old Havana, effort has also gone into rebuilding for tourist purposes, and a number of streets and squares have been rehabilitated.[29] But Old Havana is a large city, and the restoration efforts concentrate in all on less than 10% of its area.

Geography

Havana lies on the northern coast of Cuba, south of the Florida Keys, where the Gulf of Mexico joins the Atlantic Ocean. The city extends mostly westward and southward from the bay, which is entered through a narrow inlet and which divides into three main harbours: Marimelena, Guanabacoa, and Atarés. The sluggish Almendares River traverses the city from south to north, entering the Straits of Florida a few miles west of the bay.

There are low hills on which the city lies rise gently from the deep blue waters of the straits. A noteworthy elevation is the 200-foot-high (60-metre) limestone ridge that slopes up from the east and culminates in the heights of La Cabaña and El Morro, the sites of colonial fortifications overlooking the eastern bay. Another notable rise is the hill to the west that is occupied by the University of Havana and the Prince's Castle. Outside the city, higher hills rise on the west and east.

Climate

Havana, like much of Cuba, has a tropical climate that is tempered by the island's position in the belt of the trade winds and by the warm offshore currents. Under the Köppen climate classification, Havana has a tropical monsoon climate that closely borders on a tropical rainforest climate. Average temperatures range from 22 °C (72 °F) in January and February to 28 °C (82 °F) in August. The temperature seldom drops below 10 °C (50 °F). The lowest temperature was 1 °C (34 °F) in Santiago de Las Vegas, Boyeros. The lowest recorded temperature in Cuba was 0 °C (32 °F) in Bainoa, Mayabeque Province (before 2011 the eastern part of Havana province). Rainfall is heaviest in June and October and lightest from December through April, averaging 1,200 mm (47 in) annually. Hurricanes occasionally strike the island, but they ordinarily hit the south coast, and damage in Havana has been less than elsewhere in the country.

Tornadoes can be somewhat rare in Cuba, however, on the evening of January 28, 2019, a very rare strong F4 tornado struck the eastern side of Havana, Cuba's capital city. The tornado caused extensive damage, destroying at least 90 homes, killing four people and injuring 195.[30][31][32][33] By February 4, the death toll had increased to six, with 11 people still in critical condition.[34]

The table below lists temperature averages:

| Climate data for Havana (1961–1990, extremes 1859–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.4 (90.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

35.3 (95.5) |

37.0 (98.6) |

36.2 (97.2) |

35.4 (95.7) |

36.6 (97.9) |

37.7 (99.9) |

38.2 (100.8) |

39.6 (103.3) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.2 (91.8) |

39.6 (103.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.8 (78.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

29.2 (84.6) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 22.2 (72.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

26.1 (79.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.1 (79.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 18.6 (65.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

15.1 (59.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.0 (42.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 64.4 (2.54) |

68.6 (2.70) |

46.2 (1.82) |

53.7 (2.11) |

98.0 (3.86) |

182.3 (7.18) |

105.6 (4.16) |

99.6 (3.92) |

144.4 (5.69) |

180.5 (7.11) |

88.3 (3.48) |

57.6 (2.27) |

1,189.2 (46.84) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 80 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 74 | 73 | 72 | 75 | 77 | 78 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 77 | 75 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 217.0 | 203.4 | 272.8 | 273.0 | 260.4 | 237.0 | 272.8 | 260.4 | 225.0 | 195.3 | 219.0 | 195.3 | 2,831.4 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.0 | 7.2 | 8.8 | 9.1 | 8.4 | 7.9 | 8.8 | 8.4 | 7.5 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 6.3 | 7.8 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organisation,[35] Climate-Charts.com[36] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows),[37] Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun)[38] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 °C (73 °F) | 23 °C (73 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) |

Cityscape

Contemporary Havana can essentially be described as three cities in one: Old Havana, Vedado, and the newer suburban districts. Old Havana, with its narrow streets and overhanging balconies, is the traditional centre of part of Havana's commerce, industry, and entertainment, as well as being a residential area.

To the west a newer section, centred on the uptown area known as Vedado, has become the rival of Old Havana for commercial activity and nightlife. The Capitolio Nacional building marks the beginning of Centro Habana, a working-class neighborhood that lies between Vedado and Old Havana.[39] Barrio Chino and the Real Fabrica de Tabacos Partagás, one of Cuba's oldest cigar factories is located in the area.[40]

A third Havana is that of the more affluent residential and industrial districts that spread out mostly to the west. Among these is Marianao, one of the newer parts of the city, dating mainly from the 1920s. Some of the suburban exclusivity was lost after the revolution, many of the suburban homes having been nationalized by the Cuban government to serve as schools, hospitals, and government offices. Several private country clubs were converted to public recreational centres. Miramar, located west of Vedado along the coast, remains Havana's exclusive area; mansions, foreign embassies, diplomatic residences, upscale shops, and facilities for wealthy foreigners are common in the area.[41] The International School of Havana is located in the Miramar neighborhood.

In the 1980s many parts of Old Havana, including the Plaza de Armas, became part of a projected 35-year multimillion-dollar restoration project, for Cubans to appreciate their past and boost tourism. In the past ten years, with the assistance of foreign aid and under the support of local city historian Eusebio Leal Spengler, large parts of Habana Vieja have been renovated. The city is moving forward with their renovations, with most of the major plazas (Plaza Vieja, Plaza de la Catedral, Plaza de San Francisco and Plaza de Armas) and major tourist streets (Obispo and Mercaderes) near completion.

Districts

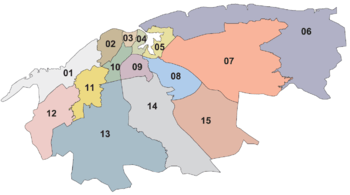

The city is divided into 15 municipalities[42] – or boroughs, which are further subdivided into 105 wards[43] (consejos populares). (Numbers refer to map).

- Playa: Santa Fe, Siboney, Cubanacán, Ampliación Almendares, Miramar, Sierra, Ceiba, Buena Vista.

- Plaza de la Revolución: El Carmelo, Vedado-Malecón, Rampa, Príncipe, Plaza, Nuevo Vedado-Puentes Grandes, Colón-Nuevo Vedado, Vedado.

- Centro Habana: Cayo Hueso, Pueblo Nuevo, Los Sitios, Dragones, Colón.

- La Habana Vieja: Prado, Catedral, Plaza Vieja, Belén, San Isidro, Jesús María, Tallapiedra.

- Regla: Guaicanimar, Loma Modelo, Casablanca.

- La Habana del Este: Camilo Cienfuegos, Cojímar, Guiteras, Alturas de Alamar, Alamar Este, Guanabo, Campo Florido, Alamar-Playa.

- Guanabacoa: Mañana-Habana Nueva, Villa I, Villa II, Chivas-Roble, Debeche-Nalon, Hata-Naranjo, Peñalver-Bacuranao, Minas-Barreras.

- San Miguel del Padrón: Rocafort, Luyanó Moderno, Diezmero, San Francisco de Paula, Dolores-Veracruz, Jacomino.

- Diez de Octubre: Luyanó, Jesús del Monte, Lawton, Vista Alegre, Goyle, Sevillano, La Víbora, Santos Suárez, Tamarindo.

- Cerro: Latinoamericano, Pilar-Atares, Cerro, Las Cañas, El Canal, Palatino, Armada.

- Marianao: CAI-Los Ángeles, Pocito-Palmas, Zamora-Cocosolo, Libertad, Pogoloti-Belén-Finlay, Santa Felicia.

- La Lisa : Alturas de La Lisa, Balcón Arimao, El Cano-Valle Grande-Bello 26 y Morado, Punta Brava, Arroyo Arenas, San Agustín, Versalles-Coronela.

- Boyeros: Santiago de Las Vegas, Nuevo Santiago, Boyeros, Wajay, Calabazar, Altahabana-Capdevila, Armada-Aldabó.

- Arroyo Naranjo: Los Pinos, Poey, Víbora Park, Mantilla, Párraga, Calvario-Fraternidad, Guinera, Eléctrico, Managua, Callejas.

- Cotorro: San Pedro-Centro Cotorro, Santa Maria del Rosario, Lotería, Cuatro Caminos, Magdalena-Torriente, Alberro.

Architecture

Due to Havana's almost five hundred-year existence, the city boasts some of the most diverse styles of architecture in the world, from castles built in the late 16th century to modernist present-day high-rises.

The present condition of many buildings in Havana has deteriorated since the 1959 Revolution.[44] Numerous collapses have resulted in injuries and deaths due to a lack of maintenance and crumbling structures.[45]

- Neoclassical

Neoclassism was introduced into the city in the 1840s, at the time including Gas public lighting in 1848 and the railroad in 1837. In the second half of the 18th century, sugar and coffee production increased rapidly, which became essential in the development of Havana's most prominent architectural style. Many wealthy Habaneros took their inspiration from the French; this can be seen within the interiors of upper-class houses such as the Aldama Palace built in 1844. This is considered the most important neoclassical residential building in Cuba and typifies the design of many houses of this period with portales of neoclassical columns facing open spaces or courtyards.

In 1925 Jean-Claude Nicolas Forestier, the head of urban planning in Paris moved to Havana for five years to collaborate with architects and landscape designers. In the master planning of the city his aim was to create a harmonic balance between the classical built form and the tropical landscape. He embraced and connected the city's road networks while accentuating prominent landmarks. His influence has left a huge mark on Havana although many of his ideas were cut short by the great depression in 1929. During the first decades of the 20th century Havana expanded more rapidly than at any time during its history. Great wealth prompted architectural styles to be influenced from abroad. The peak of Neoclassicism came with the construction of the Vedado district (begun in 1859). This area features a number of set back well-proportioned buildings in the Neoclassical style

- Colonial and Baroque

Riches were brought from the colonialists into and through Havana as it was a key transshipment point between the new world and old world. As a result, Havana was the most heavily fortified city in the Americas. Most examples of early architecture can be seen in military fortifications such as La Fortaleza de San Carlos de la Cabana (1558–1577) designed by Battista Antonelli and the Castillo del Morro (1589–1630). This sits at the entrance of Havana Bay and provides an insight into the supremacy and wealth at that time.

Old Havana was also protected by a defensive wall begun in 1674 but had already overgrown its boundaries when it was completed in 1767, becoming the new neighbourhood of Centro Habana. The influence from different styles and cultures can be seen in Havana's colonial architecture, with a diverse range of Moorish architecture, Spanish, Italian, Greek and Roman. The San Carlos and San Ambrosio Seminary (18th century) is a good example of early Spanish influenced architecture. The Havana cathedral (1748–1777) dominating the Plaza de la Catedral (1749) is the best example of Cuban Baroque. Surrounding it are the former palaces of the Count de Casa-Bayona (1720–1746) Marquis de Arcos (1746) and the Marquis de Aguas Claras (1751–1775).

- Art Deco and Eclectic

The first echoes of the Art Deco movement in Havana started in 1927, in the residential area of Miramar.[46] The Edificio Bacardi, (1930) is thought to be the best example of Art-deco architecture in the city and the first tall Art Deco building as well,[46] followed by the Hotel Nacional de Cuba (1930) and the López Serrano Building in 1932. The FOCSA Building was finished in 1956. The year 1928 marked the beginning of the reaction against the Spanish Renaissance style architecture. Art Deco started in the lush and wealthy suburbs of Miramar, Marianao, and Vedado.[46]

The city's eclectic architectural sights begins in Centro Habana.[47] The Central Railway Terminal (1912), and the Museum of the Revolution (1920) are example of Eclectic architecture.

- Modernism

_in_Vedado%2C_Havana.jpg)

Many high-rise office buildings, and apartment complexes, along with some hotels built in the 1950s dramatically altered the skyline. Modernism, therefore, transformed much of the city and is known its individual buildings of high quality rather than its larger key buildings. Examples of the latter are Habana Libre (1958), which before the revolution was the Havana Hilton Hotel and La Rampa movie theater (1955).

Famous architects such as Walter Gropius, Richard Neutra and Oscar Niemeyer all passed through the city,[48] while strong influences can be seen in Havana at this time from Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.[49] The Edificio Focsa (1956) represents Havana's economic dominance at the time. This 35-story complex was conceived and based on Corbusian ideas of a self-contained city within a city. It contained 400 apartments, garages, a school, a supermarket, and restaurant on the top floor. This was the tallest concrete structure in the world at the time (using no steel frame) and the ultimate symbol of luxury and excess. The Havana Riviera Hotel (1957) designed by Igor B. Polevitzky, a twenty-one-story edifice, when it opened, the Riviera was the largest purpose-built casino-hotel in Cuba or anywhere in the world, outside Las Vegas (the Havana Hilton (1958) surpassed its size a year later).

Landmarks and historical centres

- Habana Vieja: contains the core of the original city of Havana. It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Plaza Vieja: a plaza in Old Havana, it was the site of executions, processions, bullfights, and fiestas.

- Fortress San Carlos de la Cabaña, a fortress located on the east side of the Havana bay, La Cabaña is the most impressive fortress from colonial times, particularly its walls constructed at the end of the 18th century.

- El Capitolio Nacional: built in 1929 as the Senate and House of Representatives, the colossal building is recognizable by its dome which dominates the city's skyline. Inside stands the third largest indoor statue in the world, La Estatua de la República. Nowadays, the Cuban Academy of Sciences headquarters and the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural (the National Museum of Natural History) has its venue within the building and contains the largest natural history collection in the country.

- El Morro Castle: is a fortress guarding the entrance to Havana bay; Morro Castle was built because of the threat to the harbor from pirates.

- Fortress San Salvador de la Punta: a small fortress built in the 16th century, at the western entry point to the Havana harbour, it played a crucial role in the defence of Havana during the initial centuries of colonisation. It houses some twenty old guns and military antiques.

- Christ of Havana: Havana's 20-meter (66 ft) marble statue of Christ (1958) blesses the city from the east hillside of the bay, much like the famous Cristo Redentor in Rio de Janeiro.

- The Great Theatre of Havana: is an opera house famous particularly for the National Ballet of Cuba, it sometimes hosts performances by the National Opera. The theater is also known as concert hall, García Lorca, the biggest in Cuba.

- The Malecon/Sea wall: is the avenue that runs along the north coast of the city, beside the seawall. The Malecón is the most popular avenue of Havana, it is known for its sunsets.

- Hotel Nacional de Cuba: an Art Deco National Hotel famous in the 1950s as a gambling and entertainment complex.

- Museo de la Revolución: located in the former Presidential Palace, with the yacht Granma on display behind the museum.

- Necrópolis Cristóbal Colón: a cemetery and open-air museum,[50] it is one of the most famous cemeteries in Latin America, known for its beauty and magnificence. The cemetery was built in 1876 and has nearly one million tombs. Some gravestones are decorated with sculpture by Ramos Blancos, among others.

Coat of arms

Culture

Havana, by far the leading cultural centre of the country, offers a wide variety of features that range from museums, palaces, public squares, avenues, churches, fortresses (including the largest fortified complex in the Americas dating from the 16th through 18th centuries), ballet and from art and musical festivals to exhibitions of technology. The restoration of Old Havana offered a number of new attractions, including a museum to house relics of the Cuban revolution. The government placed special emphasis on cultural activities, many of which are free or involve only a minimal charge.

Old Havana

Old Havana, (La Habana Vieja in Spanish), contains the core of the original city of Havana, with more than 2,000 hectares it exhibits almost all the Western architectural styles seen in the New World. La Habana Vieja was founded by the Spanish in 1519 in the natural harbor of the Bay of Havana. It became a stopping point for the treasure laden Spanish Galleons on the crossing between the New World and the Old World. In the 17th century, it was one of the main shipbuilding centers. The city was built in baroque and neoclassic style.

Many buildings have fallen in ruin but a number are being restored. The narrow streets of Old Havana contain many buildings, accounting for perhaps as many as one-third of the approximately 3,000 buildings found in Old Havana.[51]

Old Havana is the ancient city formed from the port, the official center and the Plaza de Armas. Alejo Carpentier called Old Havana the place "de las columnas" (of the columns). The Cuban government is taking many steps to preserve and to restore Old Havana, through the Office of the city historian, directed by Eusebio Leal.[52] Old Havana and its fortifications were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1982. The beauty of Old Havana City attracts millions of tourists each year who enjoy its rich old culture and folk music.[53]

In spring 2015, the largest open-air art exhibition ever in Cuba took in front of the basilica on the Plaza San Francisco de Asis: Over eight weeks the United Buddy Bears visited Havana.[54] United Buddy Bears exhibitions are part of a non-commercial and non-profit project. The main aim is to promote the idea of tolerance and mutual understanding between countries, cultures and religions and to communicate a vision of a future peaceful world.[55]

Barrio Chino

Barrio Chino was once Latin America's largest and most vibrant Chinese community,[56][57][58] incorporated into the city by the early part of the 20th century. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers were brought in by Spanish settlers from Guangdong, Fujian, Hong Kong, and Macau via Manila, Philippines[59] starting in the mid-19th century to replace or work alongside African slaves.[60] After completing 8-year contracts, many Chinese immigrants settled permanently in Havana.

The first 206 Chinese-born arrived in Havana on June 3, 1847.[61] The neighborhood was booming with Chinese restaurants, laundries, banks, pharmacies, theaters and several Chinese-language newspapers, the neighborhood comprised 44 square blocks during its prime.[56][60] The heart of Barrio Chino is on el Cuchillo de Zanja (or The Zanja Canal). The strip is a pedestrian-only street adorned with many red lanterns, dancing red paper dragons and other Chinese cultural designs, there is a great number of restaurants that serve a full spectrum of Chinese dishes – unfortunately that 'spectrum' is said by many not to be related to real Chinese cuisine.

The district has two paifang (Chinese arches), the larger one located on Calle Dragones. China donated the materials in the late 1990s.[62] It has a well defined written welcoming sign in Chinese and Spanish. The smaller arch is located on Zanja strip. The Cuban's Chinese boom ended when Fidel Castro's 1959 revolution seized private businesses, sending tens of thousands of business-minded Chinese fleeing, mainly to the United States. Descendants are now making efforts to preserve and revive the culture.[57]

Visual arts

The National Museum of Fine Arts (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes) is a Fine Arts museum that exhibits Cuban and International art collections. The museum houses one of the largest collections of paintings and sculpture from Latin America and is the largest in the Caribbean region.[63] Under the Cuban Ministry of Culture, it occupies two locations in the vicinity of Havana's Paseo del Prado, these are the Palace of Fine Arts, devoted to Cuban art and the Palace of the Asturian Center, dedicated to universal art.[64] Its artistic heritage is made up of over 45,000 pieces.[65]

The Museum of the Revolution (Museo de la Revolución), designed in Havana by Cuban architect Carlos Maruri, and the Belgian Paul Belau, who came up with an eclectic design, harmoniously combines Spanish, French and German architectural elements. The museum was the Presidential Palace in the capital; today, its displays and documents outline Cuba's history from the beginning of the neo-colonial period. The building was the site of the Havana Presidential Palace Attack (1957) by the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil.

The neo-classical mansion of the Countess of Revilla de Camargo, today it is the Museum of Decorative Arts (Museo de Artes Decorativas), known as the "small French Palace of Havana" built between 1924 and 1927, it was designed in Paris inspired in French Renaissance.[66] The museum has been exhibiting more than 33,000 works dating from the reigns of Louis XV, Louis XVI, and Napoleon III; as well as 16th to 20th century Oriental pieces, among many other treasures.[67] The Museum has ten permanent exhibit halls. Among them are prominent porcelain articles from the factories in Sèvres and Chantilly, France; Meissen, Germany; and Wedgwood, England, as well as Chinese from the Qianlong Emperor period and Japanese from the Imari. The furniture comes from Stéphane Boudin, Jean Henri Riesener and several others.

Several museums in Old Havana houses furniture, silverware, pottery, glass and other items from the colonial period. One of these is the Palacio de los Capitanes Generales, where Spanish governors once lived. The Casa de Africa presents another aspect of Cuba's history, it houses a large collection of Afro-Cuban religious artifacts.

Other museums in the city include Casa de los Árabes (House of Arabs) and the Casa de Asia (House of Asia) with Middle and Far Eastern collections. Havana's Museo del Automobil has an impressive collection of vehicles dating back to a 1905 Cadillac.

While most museums of Havana are situated in Old Havana, few of them can also be found in Vedado. In total, Havana has around 50 museums, including the National Museum of Music; the Museum of Dance and Rum; the Cigar Museum; the Napoleonic, Colonial and Oricha Museums; the Museum of Anthropology; the Ernest Hemingway Museum; the José Martí Monument; the Aircraft Museum (Museo del Aire).

There are also museums of Natural Sciences, the city, Archeology, Gold-and-Silverwork, Perfume, Pharmaceuticals, Sports, Numismatics, and Weapons.

Performing arts

Facing Havana's Central Park is the baroque Great Theatre of Havana, a prominent theatre built in 1837.[68] It is now home of the National Ballet of Cuba and the International Ballet Festival of Havana, one of the oldest in the New World. The façade of the building is adorned with a stone and marble statue. There are also sculptural pieces by Giuseppe Moretti,[69] representing allegories depicting benevolence, education, music and theatre. The principal theatre is the García Lorca Auditorium, with seats for 1,500 and balconies. Glories of its rich history; the Italian tenor Enrico Caruso sang, the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova danced, and the French Sarah Bernhardt acted.

Other important theatres in the city includes the National Theater of Cuba, housed in a huge modern building located in Plaza de la Revolucion, decorated with works by Cuban artists. The National Theater includes two main theatre stages, the Avellaneda Auditorium and the Covarrubias Auditorium, as well as a smaller theatre workshop space on the ninth floor.

The Karl Marx Theater with its large auditorium have a seating capacity of 5,500 spectators, is generally used for concerts and other events, it is also one of the venues for the annual Havana Film Festival.

Festivals

- Havana Film Festival (The International Festival of New Latin American cinema)

- International Ballet Festival of Havana

- Havana International Jazz Festival

Tourism

Havana attracts over a million tourists annually,[15] the Official Census for Havana reports that in 2010 the city was visited by 1,176,627 international tourists,[15] a 20% increase from 2005.

The city has long been a popular attraction for tourists. Between 1915 and 1930, Havana hosted more tourists than any other location in the Caribbean.[70] The influx was due in large part to Cuba's proximity to the United States, where restrictive prohibition on alcohol and other pastimes stood in stark contrast to the island's traditionally relaxed attitude to leisure pursuits. A pamphlet published by E.C. Kropp Co., Milwaukee, WI, between 1921 and 1939 promoting tourism in Havana, Cuba, can be found in the University of Houston Digital Library, Havana, Cuba, The Summer Land of the World, Digital Collection.

With the deterioration of Cuba – United States relations and the imposition of the trade embargo on the island in 1961, tourism dropped drastically and did not return to anything close to its pre-revolution levels until 1989. The revolutionary government in general, and Fidel Castro in particular, initially opposed any considerable development of the tourism industry, linking it to the debauchery and criminal activities of times past. In the late 1970s, however, Castro changed his stance and, in 1982, the Cuban government passed a foreign investment code which opened a number of sectors, tourism included, to foreign capital.

Through the creation of firms open to such foreign investment (such as Cubanacan), Cuba began to attract capital for hotel development, managing to increase the number of tourists from 130,000 (in 1980) to 326,000 (by the end of that decade).

Havana has also been a popular health tourism destination for more than 20 years. Foreign patients travel to Cuba, Havana in particular, for a wide range of treatments including eye-surgery, neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease, and orthopaedics. Many patients are from Latin America, although medical treatment for retinitis pigmentosa, often known as night blindness, has attracted many patients from Europe and North America.[71][72]

Economy

Industry

Havana has a diversified economy, with traditional sectors, such as manufacturing, construction, transportation and communications, and new or revived ones such as biotechnology and tourism.

The city's economy first developed on the basis of its location, which made it one of the early great trade centres in the New World. Sugar and a flourishing slave trade first brought riches to the city, and later, after independence, it became a renowned resort. Despite efforts by Fidel Castro's government to spread Cuba's industrial activity to all parts of the island, Havana remains the centre of much of the nation's industry.

The traditional sugar industry, upon which the island's economy has been based for three centuries, is centred elsewhere on the island and controls some three-fourths of the export economy. But light manufacturing facilities, meat-packing plants, and chemical and pharmaceutical operations are concentrated in Havana. Other food-processing industries are also important, along with shipbuilding, vehicle manufacturing, production of alcoholic beverages (particularly rum), textiles, and tobacco products, particularly the world-famous Habanos cigars.[73] Although the harbours of Cienfuegos and Matanzas, in particular, have been developed under the revolutionary government, Havana remains Cuba's primary port facility; 50% of Cuban imports and exports pass through Havana. The port also supports a considerable fishing industry.

In 2000, nearly 89% of the city's officially recorded labour force worked for government-run agencies, institutions or enterprises. Havana, on average, has the country's highest incomes and human development indicators. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba re-emphasized tourism as a major industry leading to its recovery. Tourism is now Havana and Cuba's primary economic source.[74]

Havana's economy is still in flux, despite Raul Castro's embrace of free enterprise in 2011. Though there was an uptick in small businesses in 2011, many have since gone out of business, due to lack of business and income on the part of the local residents, whose salaries average $20 per month.[75]

Commerce and finance

After the Revolution, Cuba's traditional capitalist free-enterprise system was replaced by a heavily socialized economic system. In Havana, Cuban-owned businesses and U.S.-owned businesses were nationalized and today most businesses operate solely under state control.

In Old Havana and throughout Vedado there are several small private businesses, such as shoe-repair shops or dressmaking facilities. Banking as well is also under state control, and the National Bank of Cuba, headquartered in Havana, is the control center of the Cuban economy. Its branches in some cases occupy buildings that were in pre-revolutionary times the offices of Cuban or foreign banks.

In the late 1990s Vedado, located along the atlantic waterfront, started to represent the principal commercial area. It was developed extensively between 1930 and 1960, when Havana developed as a major destination for U.S. tourists; high-rise hotels, casinos, restaurants, and upscale commercial establishments, many reflecting the art deco style.[76]

Vedado is today Havana's financial district, the main banks, airline companies offices, shops, most businesses headquarters, numerous high-rise apartments and hotels, are located in the area.[77] The University of Havana is located in Vedado.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1750 | 70,000 | — |

| 1931 | 728,500 | +940.7% |

| 1943 | 868,426 | +19.2% |

| 1953 | 1,139,579 | +31.2% |

| 1970 | 1,786,522 | +56.8% |

| 1981 | 1,929,432 | +8.0% |

| 2002 | 2,171,671 | +12.6% |

| 2012 | 2,106,146 | −3.0% |

| 2018 | 2,131,480 | +1.2% |

By the end of 2012 official Census, 19.1% of the population of Cuba lived in Havana.[5] According to the census of 2012, the population was 2,106,146.[5] The city has an average life expectancy of 76.81 years at birth.[5] In 2009, there were 1,924 people living with HIV/AIDS in the city, 78.9% of these are men, and 21.1% being women.[78]

According to the 2012 official census (the Cuban census and similar studies use the term "skin colour" instead of "race").[5]

- White: 58.4%, (Spanish descent were most common)[5][79]

- Mestizo or Mulatto (mixed race): 26.4%

- Black: 15.2%

- Asian: 0.2%[79]

There are few mestizos in contrast to many other Latin American countries, because the Native Indian population was virtually wiped out by Eurasian diseases in colonial times.[80]

Havana agglomeration grew rapidly during the first half of the 20th century reaching 1 million inhabitants in the 1943 census. The con-urbanization expanded over the Havana municipality borders into neighbor municipalities of Marianao, Regla and Guanabacoa. Starting from the 1980s, the city's population is growing slowly as a result of balanced development policies, low birth rate, its relatively high rate of emigration abroad, and controlled domestic migration. Because of the city and country's low birth rate and high life expectancy,[4][81] its age structure is similar to a developed country, with Havana having an even higher proportion of elderly than the country as a whole.[5]

The Cuban government controls the movement of people into Havana on the grounds that the Havana metropolitan area (home to nearly 20% of the country's population) is overstretched in terms of land use, water, electricity, transportation, and other elements of the urban infrastructure. There is a population of internal migrants to Havana nicknamed "palestinos" (Palestinians),[82] sometimes considered a racist term,[83] these mostly hail from the eastern region of Oriente.[84]

The city's significant minority of Chinese, mostly Cantonese ancestors, were brought in the mid-19th century by Spanish settlers via the Philippines with work contracts and after completing 8-year contracts many Chinese immigrants settled permanently in Havana.[79] Before the revolution the Chinese population counted to over 200,000,[85] today, Chinese ancestors could count up to 100,000.[86] Chinese born/ native Chinese (mostly Cantonese as well) are around 400 presently.[87] There are some 3,000 Russians living in the city; as reported by the Russian Embassy in Havana, most are women married to Cubans who had studied in the Soviet Union.[88] Havana also shelters other non-Cuban population of an unknown size. There is a population of several thousand North African teen and pre-teen refugees.[89]

Religion

Roman Catholics form the largest religious group in Havana. Havana is one of the three Metropolitan sees on the island (the others being Camagüey and Santiago), with two suffragan bishoprics: Matanzas and Pinar del Río. Its patron saint is San Cristobal (Saint Christopher), to whom the cathedral is devoted. it also has a minor basilica, Basílica Santuario Nacional de Nuestra Señora de la Caridad del Cobre and two other national shrines, Jesús Nazareno del Rescate and San Lázaro (El Rincón). It received papal visits from three successive supreme pontiffs: Pope John Paul II (January 1998), Pope Benedict XVI (March 2012) and Pope Francis (September 2015).

The Jewish community in Havana has reduced after the Revolution from once having embraced more than 15,000 Jews,[90] many of whom had fled Nazi persecution and subsequently left Cuba to Miami or moved to Israel after Castro took to power in 1959. The city once had five synagogues, but only three remain (one Orthodox, and two Conservative: one Conservative Ashkenazi and one Conservative Sephardic), Beth Shalom Grand Synagogue is one of them and another that is a hybrid of all 3 put together. In February 2007 the New York Times estimated that there were about 1,500 known Jews living in Havana.[91]

Poverty and slums

| Housing Units and Population of Havana Slums[92][93] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing type | Year | Units | Population | % of Total Pop. | ||||

| cuartería(a) | 2001 | 60,754 | 206,564 | 9.4 | ||||

| slums | 2001 | 21,552 | 72,986 | 3.3 | ||||

| shelters | 1997 | 2,758 | 9,178 | 0.4 | ||||

| (a)A cuartería (or ciudadela, solar) is a large inner-city old mansion or hotel or boarding house subdivided into rooms, sometimes with over 60 families.[94] | ||||||||

The years after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the city, and Cuba in general have suffered decades of economic deterioration, including Special Period of 1990s.[95] The national government does not have an official definition of poverty.[96] The government researchers argue that "poverty" in most commonly accepted meanings does not really exist in Cuba, but rather that there is a sector of the population that can be described as "at risk" or "vulnerable" using internationally accepted measures.[96]

The generic term "slum" is seldom used in Cuba, substandard housing is described: housing type, housing conditions, building materials, and settlement type. The National Housing Institute considers units in solares (a large inner-city mansion or older hotel or boarding house subdivided into rooms, sometimes with over 60 families)[94] and shanty towns to be the "precarious housing stock" and tracks their number. Most slum units are concentrated in the inner-city municipalities of Old Havana and Centro Habana, as well as such neighbourhoods as Atarés in Regla.[93] People living in slums have access to the same education, health care, job opportunities and social security as those who live in formerly privileged neighbourhoods. Shanty towns are scattered throughout the city except for in a few central areas.[93]

Over 9% of Havana's population live in cuartería (solares, ciudadela), 3.3% in shanty towns, and 0.3% in refugee shelters.[92][93] This does not include an estimate of the number of people living in housing in "fair" or "poor" condition because in many cases these units do not necessarily constitute slum housing but rather are basically sound dwellings needing repairs. According to Instituto Nacional de Vivienda (National Housing Institute) official figures, in 2001, 64% of Havana's 586,768 units were considered in "good" condition, up from 50% in 1990. Some 20% were in "fair" condition and 16% in "poor" condition.[93] Partial or total building collapses are not uncommon, although the number had been cut in half by the end of the 1990s as the worst units disappeared and others were repaired. Buildings in Old Havana and Centro Habana are especially exposed to the elements: high humidity, the corrosive effects of salt spray from proximity to the coast, and occasional flooding. Most areas of the city, specially the highly-populated districts, are in urban decay.[97]

Transport

Urban buses

The city's public buses is carried out by the Empresa Provincial de Transporte de La Habana (EPTH).

- Metrobus

The Red Principal, previously known as MetroBus, serves the inner-city urban area, with a maximum distance of 20 km (12 mi).[98] The Red Principal consists of 17 main lines, identified with the letter "P" with long-distance routes. The stops are usually 800–1,000 metres (2,600–3,300 ft), with frequent buses in peak hours, about every 10 minutes. It uses large modern articulated buses, such as the Chinese-made Yutong brand, Russian-made Liaz, or MAZ of Belarus.

- Red Alimentadora

The Red Alimentadora, known as the feeder line, connects the adjacent towns and cities in the metropolitan area with the city center, with a maximum distance of 40 km (25 mi).[98] This division has one of the most used and largest urban bus fleets in the country, its fleet is made up of mostly new Chinese Yutong buses.[99] In 2008 the Cuban government invested millions of dollars for the acquisition of 1,500 new Yutong urban buses.

Airports

Havana is served by José Martí International Airport. The Airport lies about 11 kilometres (7 mi) south of the city center, in the municipality of Boyeros, and is the main hub for the country's flag carrier Cubana de Aviación. The airport is Cuba's main international and domestic gateway, it connects Havana with the rest of the Caribbean, North, Central and South America, Europe and one destination in Africa.

The city is also served by Playa Baracoa Airport which is small airport to the west of city used for some domestic flights, primarily Aerogaviota.

Rail

Havana has a network of suburban, interurban and long-distance rail lines. The railways are nationalised and run by the FFCC (Ferrocarriles de Cuba – Railways of Cuba). The FFCC connects Havana with all the provinces of Cuba. The main railway stations are: Central Rail Station, La Coubre Rail Station, Casablanca Station, and Estación de Tulipán.

In 2004 the annual passenger volume was some 11 million,[98] but demand is estimated at two-and-a-half to three times this value, with the busiest route being between Havana and Santiago de Cuba, some 836 kilometres (519 mi) apart by rail. In 2000 the Union de Ferrocarriles de Cuba bought French first class airconditioned coaches.

In the 1980s there were plans for a Metro system in Havana similar to Moscow's, as a result of the Soviet Union influence in Cuba at the time. The studies of geology and finance made by Cuban, Czech and Soviet specialists were already well advanced in the 1980s.[100] The Cuban press showed the construction project and the course route, linking municipalities and neighborhoods in the capital.[100] In the late 1980s the project had already begun, each mile of track was worth a million dollars at the time, but with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 the project was later dropped.[100]

Interurban (tram)

An interurban line, known as the Hershey Electric Railway, built in 1917 runs from Casablanca (across the harbor from Old Havana) to Hershey and on to Matanzas.[101]

Tramway

Havana operated a tram system until 1952, which began as a horsecar system, Ferro Carril Urbano de la Habana in 1858,[102] merged with rival coach operator in 1863 as Empresa del Ferro-Carril Urbano y Omnibus de La Habana and later electrified in 1900 under new foreign owners as Havana Electric Railway Company.[103] Ridership decline resulted in bankruptcy in 1950 with new owner Autobus Modernos SA abandoning systems in favor of buses and sold the remaining cars were sold to Matanzas in 1952.

Ferry

Ferries connect Old Havana with Regla and Casablanca, leaving every 10–15 minutes from Muelle Luz (at the foot of Santa Clara Street). The fare is CUP 0.20¢.[104]

Roads

The city's road network is quite extensive, and has broad avenues, main streets and major access roads to the city such as the Autopista Nacional (A1), Carretera Central and Via Blanca. The road network has been under construction and growth since the colonial era but is undergoing a major deterioration due to low maintenance.[105]

Motorways (autopistas) include:

- A1 – Autopista Nacional, from Havana to Santa Clara and Sancti Spiritus, with additional short sections near Santiago and Guantanamo

- A4 – Autopista Este-Oeste, from Havana to Pinar del Río

- Via Blanca, to Matanzas and Varadero

- Havana ring road (Spanish: Primer anillo), which starts at a tunnel under the entrance to Havana Harbor

- Autopista del Mediodia, from Havana to San Antonio de los Baños

- an autopista from Havana to Melena del Sur

- an autopista from Havana to Mariel

Administration

The governor is Reinaldo García Zapata,[12] he was elected on January, 2020.[11]

The city is administered by a city-provincial council, with a governor as chief administrative officer,[106] thus Havana functions as both a city and a province. The city has little autonomy and is dependent upon the national government, particularly, for much of its budgetary and overall political direction.

The national government is headquartered in Havana and plays an extremely visible role in the city's life. Moreover, the all-embracing authority of many national institutions has led to a declining role for the city government, which, nevertheless, still provides much of the essential services and has competences in education, health care, city public transport, garbage collection, small industry, agriculture, etc.

Voters elect delegates to Municipal Assemblies in competitive elections. There is only one political party, the Communist Party, but since there must be a minimum of two candidates, members of the Communist Party often run against each other. Candidates are not required to be members of the party. They are nominated directly by citizens in open meetings within each election district. Municipal Assembly delegates in turn elect members of the Provincial Assembly, which in Havana serves roughly as the City Council; its president functions as the Mayor. There are direct elections for deputies to the National Assembly based on slates, and a portion of the candidates is nominated at the local level. The People's Councils (Consejos Populares) consist of local municipal delegates who elect a full-time representative to preside over the body. In addition, there is participation from "mass organisations" and representatives of local government agencies, industries and services. The 105 People's Councils in Havana cover an average of 20,000 residents.

Havana city borders are contiguous with the Mayabeque Province on the south and east and to Artemisa Province on the west, since former La Habana Province (rural) was abolished in 2010.

Infrastructure

Education

The national government assumes all responsibility for education, and there are adequate primary, secondary, and vocational training schools throughout Cuba. The schools are of varying quality and education is free and compulsory at all levels except higher learning, which is also free.

The University of Havana, located in the Vedado section of Havana, was established in 1728 and was regarded as a leading institution of higher learning in the Western Hemisphere. Soon after the Revolution, the university, as well as all other educational institutions, were nationalized. Since then several other universities have opened, like the Higher Learning Polytechnic Institute José Antonio Echeverría where the vast majority of today's Cuban engineers are taught.

The Cuban National Ballet School with 4,350 students is one of the largest ballet schools in the world and the most prestigious ballet school in Cuba.[107]

Health

All Cuban residents have free access to health care in hospitals,[108] local polyclinics, and neighborhood family doctors who serve on average 170 families each,[109] which is one of the highest doctor-to-patient ratio in the world.[110] However, the health system has suffered from shortages of supplies, equipment and medications caused by ending of the Soviet Union subsidies in the early 1990s and the US embargo.[111] Nevertheless, Havana's infant mortality rate in 2009 was 4.9 per 1,000 live births,[5] 5.12 in the country as a whole, which is lower than many developed nations,[112][113] and the lowest in the developing world.[112][113][114] Administration of the health care system for the nation is centered largely in Havana. Hospitals in Havana are run by the national government, and citizens are assigned hospitals and clinics to which they may go for attention.

Services

Utility services are under the control of several nationalized state enterprises that have developed since the Cuban revolution. Water, electricity, and sewage service are administered in this fashion. Electricity is supplied by generators that are fueled with oil. Much of the original power plant installations, which operated before the Revolutionary government assumed control, have become somewhat outdated. Electrical blackouts occurred, prompting the national government in 1986 to allocate the equivalent of $25,000,000 to modernize the electrical system.

Sports

Many Cubans are avid sports fans who particularly favour baseball. Havana's team in the Cuban National Series is Industriales. FCBA. The city has several large sports stadiums, the largest one is the Estadio Latinoamericano. Admission to sporting events is generally free, and impromptu games are played in neighborhoods throughout the city. Social clubs at the beaches provide facilities for water sports and include restaurants and dance halls.

- Havana was host to the 11th Pan American Games in 1991.[115] Stadiums and facilities for this were built in the relatively unpopulated eastern suburbs.

- Havana was host to the 1992 IAAF World Cup in Athletics.[116]

- Havana was an applicant to host the 2008 Summer Olympics and 2012 Summer Olympics,[117] but was not shortlisted.

Notable people

Notable people originally from Havana:

International relations

Diplomatic offices

As Cuba's national capital and seat of government, Havana hosts 88 embassies (including the papal apostolic nunciature, traditionally manned by a titular archbishop). Furthermore, there are 11 consulates(-general) and a trade office.[10]

- Embassies

|

|

Twin towns – sister cities

Havana is twinned with:

|

|

Note: Some of the city's municipalities are also twinned to small cities or districts of other big cities, for details see their respective articles.

See also

- Largest cities in the Americas

- List of cities in the Caribbean

Notes

- "How Obama's US-Cuba deal could shape Havana's future". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Anuario Demográfico de Cuba 2018" (PDF) (in Spanish). Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información. June 2019.

- "Subnational Human Development Index". Global Data Lab. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Cuba". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- "Población total por color de la piel según provincias y municipios" (PDF). 2012 Official Census. Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2013.

- "Largest Cities in the Caribbean".

- "Havana". The Free Dictionary.

capital of Spanish Cuba in 1552

- "Old Havana". www.galenfrysinger.com.

- (in English) Spanish–American War, Effects of the Press on Spanish-American Relations in 1898

- "Cuba - Embassies and Consulates". Embassypages.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- San Miguel, Raúl (18 January 2020). "Electos el Gobernador y Vicegobernadora en La Habana". Tribuna de La Habana (in Spanish).

- (in Spanish) Preside Esteban Lazo toma de posesión de las autoridades de Gobierno en La Habana

- "Workforce and Salary (Section 4.5)" (in Spanish and English). ONE- Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas – Republica de Cuba. Archived from the original on 2010-12-16.

- "Anuario Estadistico de Ciudad de La Habana" (in Spanish). ONE – Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas (National Statistics Office). Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- "Section 15 (Turismo), article 15.7 (Visitantes por mes)" (in Spanish). ONE- Oficina de Estadisticas de Cuba. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- "Old Havana and its Fortification System". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO.ORG.

- Goodsell, James Nelson (April 11, 2017). "Havana". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Havana climate summary". Weatherbase. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- (in Spanish) Fundación de La Habana a orillas del Río Onicajinal o Mayabeque

- "San Cristobal de La Habana en el Sur". Mayabeque.blogia.com. 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- C Cumo. The Ongoing Columbian Exchange: Stories of Biological and Economic Transfer in World History: Stories of Biological and Economic Transfer in World History Page 356 ISBN 978-1610697958 https://books.google.com/books?id=tzqhBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA356&dq=An+epidemic+kills+a+third+of+cuban+population+1649&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjYwIyV0vzbAhWus1kKHb49ASQQ6AEILzAB#v=onepage&q=An%20epidemic%20kills%20a%20third%20of%20cuban%20population%201649&f=false

- Thomas, Hugh (1998). Cuba, or The pursuit of freedom (2nd ed.). Da Capo Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780306808272.

- Harbron, John D..Trafalgar and the Spanish navy, Lestrange Maritime Press, 2004, ISBN 0-87021-695-3, pp. 15–17. Havana built nearly 50% more Ships of the Line than any other Spanish dockyard during the 18th century.

- Pocock, Tom (1998). "Chapter Six". Battle for Empire: The very first world war 1756–63. Michael O'Mara Books. ISBN 9781854793904.

- Thomas, Hugh: Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom 2nd edition. Chapter One

- Cantón Navarro, José (2001). History of Cuba: The Challenge of the Yoke and the Star : Biography of a People. Editoral SI-MAR. p. 81. ISBN 9789597054757.

- Moruzzi, Peter (2018). HAVANA BEFORE CASTRO : when Cuba was a tropical playground. Gibbs Smith. ISBN 1423603672.

- Nigel Hunt. "Cuba Nationalization Laws". cuba heritage .org. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- "Elogian capital humano en restauración de La Habana". Digital Granma Internacional (in Spanish). 7 December 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007.

- "Havana tornado: Cuba's capital hit by rare twister". BBC News. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- "The Latest: Havana hit by Category F3 tornado". StarTribune.com. Associated Press. 28 January 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-01-29.

- Guy, Jack (28 January 2019). "Huge tornado in Cuba kills 4 and injures 195". CNN.

- Cappucci, Matthew (28 January 2019). "A deadly tornado plowed through Havana on Sunday night. Here's how it happened". The Washington Post. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "Death Toll Rises to Six From Rare Havana Tornado". Weather Underground. 4 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- "World Weather Information Service – Havana". Cuban Institute of Meteorology. June 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- "Casa Blanca, Habana, Cuba: Climate, Global Warming, and Daylight Charts and Data". Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- "Station La Havane" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- "Klimatafel von Havanna (La Habana, Obs. Casa Blanca) / Kuba" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- Centro Habana Archived May 19, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – Centro Habana guia turistica, Cuba

- CubaJunky.com. "Centro Habana". Cuba-junky.com. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- "Havana Miramar School". Cactuslanguage.com. Archived from the original on 2010-02-08. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Population by Province and Municipality

- "Oficial Statistics for Havana" (in Spanish). Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas de Cuba (ONE). Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Rainsford, Sarah (2012-05-17). "Cuba's crumbling buildings mean Havana housing shortage". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-02-24.

- "Old Havana Building Collapse Kills Four - Havana Times.org". www.havanatimes.org. Retrieved 2017-02-24.

- Alonso, Alejandro (2003). Havana Deco. New York: W.W. Norton and Company. pp. 3–7. ISBN 978-0-393-73232-0.

- Sainsbury, Brendan (2007). Havana. Lonely planet. pp. 101–02. ISBN 978-1-74104-069-2.

- Juliet, Barclay (1993). Havana, Portrait of a City. London: Casell. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-84403-127-6.

- Rodriguez, Eduardo-Luis (1999). "Introduction". The Havana guide: modern architecture. New York City: Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-1-56898-210-6.

- "Havana's magnificent necropolis tells a story of wealth and freedom". Carilat.de. Archived from the original on 2009-08-01. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- Travel Photos of Galen R Frysinger, Sheboygan, Wisconsin 3,000 buildings found in Old Havana

- Hartford Web Publishing Cuban Restoration Project Pins New Hopes on Old Havana

- Habana Vieja – UNESCO World Heritage List

- United Buddy Bears in Havana 2015

- Bears in Havana: Another Step for Tolerance

- Havana's Chinatown Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – The once largest Chinese community in Latin America

- China Today Chinese in Cuba

- Embassy of Cuba in Beijing, History of Chinese in Cuba Surgido en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, el Barrio Chino de La Habana experimentó un rápido desarrollo y llegó a convertirse, en la siguiente centuria, en el más importante de América Latina.

- Rafael Lam "Chinese from Manila in Cuba"

- Embassy of Cuba in Beijing-Immigration in Cuba Archived February 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Cuba Culture "Aportes de los chinos en Cuba"

- El Barrio Chino de la Habana – Havana's Barrio Chino (in Spanish)

- "Historia del Museo Nacional". Museonacional.cult.cu (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- "Centro Asturiano". MuseoNacional.cult.cu. Archived from the original on 2008-02-12. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- "(ES) El Alma de la nación no se vende". Cubaweb.cu. Archived from the original on 22 August 2001. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Museo de Artes Decorativos- José Gómez Mena, one of Cuba's wealthiest aristocrats, built this house in 1927 to hold his staggering collection of antique furniture, rugs, paintings and vases.

- (in Spanish) Paseos por La Habana Archived October 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine-El museo guarda en su interior mobiliario antiguo, porcelana y ceramica, cristalerias, espejos, bronces y objetos ornamentales.

- "170 Aniversario Gran Teatro". Archived from the original on 2019-01-08. Retrieved 2019-01-07.

- (in Spanish) Radio Havana-Cuba- Existen también piezas escultóricas en las cuatro cúpulas del techo realizadas por Giuseppe Moretti.

- International Tourism and the Formation of Productive Clusters in the Cuban Economy Miguel Alejandro Figueras

- A Novel Tourism Concept Archived January 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Caribbean News Net

- Fawthrop, Tom (21 November 2003). "Cuba sells its medical expertise". BBC News.

- "The economy of Havana". Macalester.edu. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- "Tourism in Cuba during the Special Period" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-25. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- AP (27 December 2013). "Lack of Customers Dooms Many Cuban Businesses". Weekly Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- "De una casa colonial a una mansión del Vedado" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 October 2004. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- "britannica.com". britannica.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Official Census, people living with HIV/AIDS in Havana

- Embassy of Cuba in Beijing – History of Immigration in Cuba Archived 2009-02-03 at the Wayback Machine "The first (immigrants) came from various regions of Spain, mostly peasants from the Canaries and Galicia, which like those from China, were subjected to conditions of living and working conditions similar to those of slaves."

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A–M. ABC-CLIO. p. 413. ISBN 0-313-34102-8.

- "Millennium Indicators". Mdgs.un.org. 2010-06-23. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- LARRY ROHTERPublished: October 20, 1997 (1997-10-20). "Cuba's Unwanted Refugees Squatters in Havana's Shantytowns". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- AlJazeera A Palestinian filmmaker finds much in common with a homeless Cuban musician.

- "Castro's Cuba in Perspective". Isreview.org. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- Havana's Chinatown Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – Cuba's Chinese population before the Revolution

- CIA World Factbook. Cuba. 2006. September 6, 2006. Archived May 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- In Havana there are now about 400 native Chinese, but their presence is being felt like a million ("En La Habana quedan hoy unos 400 chinos oriundos, pero su presencia se está haciendo sentir como si fueran un millón".)

- (in Spanish) Russians in Cuba Los rusos que se quedaron en la isla -unos 3.000 actualmente- son en su mayoría mujeres como Marina o Natalia que se casaron con cubanos que habían ido a la URSS a estudiar, indicó la embajada rusa en La Habana.

- "Sahrawi children inhumanely treated in Cuba, former Cuban official". MoroccoTimes.com. 31 March 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-11-25. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- Present-Day Jewish Life in Cuba

- 1,500 Jews who live in Cuba; 1,100 reside in Havana, and the remaining 400 are spread among the provinces. In Cuba, Finding a Tiny Corner of Jewish Life.

- INV, Instituto Nacional de la Vivienda (2001a) Boletín Estadístico Anual. 2001. INV, Havana.

- González Rego, R. 1999. "Una Primera Aproximación al Análisis Espacial de los Problemas Socioambientales en los Barrios y Focos Insalubres de Ciudad de La Habana". Facultad de Filosofía e Historia. Departamento de Sociología, Universidad de La Habana. 250 p.

- Dick Cluster; Rafael Hernández (2006). The History of Havana. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-4039-7107-4.

- Burnett, Victoria. "Cuba - Overview". New York Times. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Angela, Ferriol Maruaga; et al: Cuba crisis, ajuste y situación social (1990–1996), La Habana, Cuba : Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1998, Champter 1

- "Havana's former grandeur decays and crumbles". Reuters. 2007-03-24. Retrieved 2020-07-17.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 22, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) National Statistics Census of Cuba – Transportation p. 6

- "International transportation fair in Havana Business in excess of $100 million, Granma national newspaper note". Web.archive.org. 2004-10-30. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- Havana Metro Archived January 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Hace unos años parecía que la capital cubana tendría metro, cuando en la década de 1980 los estudios de geología y finanzas realizados por especialistas cubanos y soviéticos iban muy adelantados.

- Conner Gorry; David Stanley (2004). Cuba. Lonely Planet. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-74059-120-1.

- http://www.tramz.com/cu/hb/hb.html

- http://www.tramz.com/cu/hb/hbb.html

- ""Havana", Lonely Planet". Lonelyplanet.com. Archived from the original on 2009-02-28. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- "Transporte publico en La Habana" (in Spanish). Mundo Viajero. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Cuba elige gobernadores ajustándose a nueva Constitución

- (in Spanish) La Escuela Nacional de Ballet Archived 2009-06-23 at the Wayback Machine – La Escuela desarrolla una experiencia única en el mundo, enmarcada en la Batalla de Ideas.

- Harvard Public Health Review/Summer 2002 Archived 2012-05-30 at Archive.today The Cuban Paradox

- Medical know-how boosts Cuba's wealth BBC online.

- Commitment to health: resources, access and services Archived July 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine United Nations Human Development report

- The effects of the U.S. embargo on medicines in Cuba have been studied in numerous reports.

• R Garfield and S Santana. Columbia University, School of Nursing, New York; "The impact of the economic crisis and the US embargo on health in Cuba" "this embargo has raised the cost of medical supplies and food Rationing, universal access to primary health services"

• American Association for World Health; Online. American Association for World Health Report. March 1997. Accessed 6 October 2006. Supplementary source : American Public Health Association website Archived August 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine "After a year-long investigation, the American Association for World Health has determined that the U.S. embargo of Cuba has dramatically harmed the health and nutrition of large numbers of ordinary Cuban citizens."

• Felipe Eduardo Sixto; An evaluation of Four decades of Cuban Healthcare Archived June 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

"The lack of supplies accompanied by a deterioration of basic infrastructure (potable water and sanitation) resulted in a setback of many of the previous accomplishments. The strengthening of the U.S. embargo contributed to these problems."

• Pan American Health organization; Health Situation Analysis and Trends Summary Regional Core Health Data System – Country Profile: CUBA Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine "The two determining factors underlying the crisis are well known. One is the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc, and the other is the economic embargo the Government of the United States."

• Harvard Public Health; Review/Summer 2002 : The Cuban Paradox Archived 2012-05-30 at Archive.today "Because its access to traditional sources of financing is seriously hindered by the sanctions, which until recently included all food and medicine, Cuba has received little foreign and humanitarian aid to maintain the vitality of its national programs"

• The Lancet medical journal; Role of USA in shortage of food and medicine. "The resultant lack of food and medicines to Cuba contributed to the worst epidemic of neurological disease this century." - United Nations World Population Prospects: 2011 revision Archived 2013-06-03 at the Wayback Machine – 2011 revision

- CIA World Factbook 2009 Archived March 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "Cuba tiene la menor mortalidad infantil del mundo en desarrollo, según UNICEF". Publico.es. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- "Havana '91 Quadro de Medalhas". Panamerican Games '91 (in Portuguese). quadrodemedalhas.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- "IAAF WORLD CUP IN ATHLETICS". gbrathletics.com. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Olympic bids: The rivals". BBC.co.uk. 2003-07-15. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- https://www.rte.ie/news/2016/1128/834875-fidel-castro-death-cuba/