Luis Barragán House and Studio

Luis Barragán House and Studio, also known as Casa Luis Barragán, is the former residence of architect Luis Barragán in Miguel Hidalgo district, Mexico City.[1] It is owned by the Fundación de Arquitectura Tapatía and the Government of the State of Jalisco. It is now a museum exhibiting Barragán's work and is also used by visiting architects.[2] It retains the original furniture and Barragán's personal objects. These include a mostly Mexican art collection spanning the 16th to 20th century, with works by Picasso, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Jesús Reyes Ferreira and Miguel Covarrubias.

| Luis Barragán House | |

|---|---|

Casa Luis Barragán | |

The staircase in the reading room, one of the best known details of the house | |

| |

| General information | |

| Location | Mexico City, Mexico |

| Coordinates | 19°24′39″N 99°11′32″W |

| Completed | 1947 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Luis Barragán |

| Official name | Luis Barragán House and Studio |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii |

| Designated | 2004 (28th session) |

| Reference no. | 1136 |

| State Party | Mexico |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

Located in the west of Mexico City, the residence was built in 1948 after the Second World War. It reflects Barragán's design style during this period and remained his residence until his death in 1988. In 1994 it was converted into a museum, run by Barragán's home state of Jalisco and the Arquitectura Tapatía Luis Barragán Foundation, with tours available only by appointment. In 2004, it was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO because it is one of the most influential and representative examples of modern Mexican architecture.[3]

History

The area of the house was originally just outside the historic town of Tacubaya.[4] The house was built on property that Barragán probably purchased in 1939 as part of a larger development at a time when his career was shifting from real estate to architecture. He eventually sold the rest of the land, keeping that area for himself.[5] The predecessor to the house is the “Ortega House,” which made use of a preexisting building. Barragán lived there from 1943 to 1947.[5] The house was designed and built in 1947 for Luz Escandón de R. Valenzuela, but in 1948, Barragán decided to move into it himself, despite the fact that at the time he was developing the elite subdivision Jardines del Pedregal in the south of the city.[5][6] Barragán lived there until his death in 1988, and during this time the house underwent many modifications, functioning as a kind of laboratory for his ideas.[5][7][8]

In 1993, the government of the state of Jalisco and Arquitectura Tapatía Luis Barragán Foundation acquired the house, turning it into a museum in 1994.[9] In 2004, it was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, the only private residence in Latin America to be named so. It was named because of its representation of 20th-century architecture, which integrated traditional and vernacular elements and mixes various philosophical and artistic tendencies of the mid 20th century.[4][8] It has also named as one of the ten most important houses constructed in the 20th century. It has also been the subject of various publications including the book, “La casa de Luis Barragán,” written by three experts on Barragán's work.[7] Despite its importance, the house is little known to Mexico City tourism, generally visited by architects and art aficionados from various parts of the world.[8][10]

The museum

The house was completely restored in 1995 at a cost of 250,000 pesos for its function as a museum, with money coming from CONACULTA, the national lottery and the Jalisco government.[9] As a key piece of 20th-century architecture in Mexico, the house itself is the main exhibition. It retains the original furniture and Barragán's personal objects. These include a mostly Mexican art collection spanning the 16th to 20th century, with works by Picasso, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Jesús Reyes Ferreira and Miguel Covarrubias.[4][9] Reyes Ferreria was particularly appreciated with the house collection contains one of his few oils.[6] Guided tours are offered but a previous appointment is necessary.[11] The museum is run by the state of Jalisco (Barragán's home state) and the Arquitectura Tapatía Luis Barragán Foundation.[8] It maintains a library of about 3,000 publications and personal papers and photographs.[12][13] It has also partnered with Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education to create a faculty position named after the architect.[13]

The museum also hosts events such as conferences, presentation and art exhibits.[4][11] Its book presentation have those about the architect and his works such as “Barragán, obra completa”.[9] Temporary exhibits held at the house include that of Jorge Yázpk (2008), Azul Pacífico by Sofía Taboas (2008), Homenaje al cuadrado by Josef Albers (2007), Equus by Teresas Zimbrón (2007), Little did he know by Aldo Chaparro, Mauricio Garcia Torre and Mauricio Limón (2007), Frederic Amat (2006), Luciano Matus (2006), La mancha by Santiago Borja (2006), Valeria Florescano (2004),[14] Alberto Moreno, (2008), José Limón (2008), Intervenciones a la aquitectura by Humberto Spindola (2009), SANAA by Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa (2009) and one by Francisco Ugarte (2010) .[15]

In the early 2000s, the house hosted a year-long project called El aire es azul (The air is blue) with twenty one international artists who spent the time in the house creating art inspired by the house. These artists included Pedro Reyes, Claudia Fernandez, Damian Ortega, Anri Sala and Koo Jeon-A.[12][16]

Luis Barragán

Luis Barragán Morfin was born in 1902 in Guadalajara to a wealthy family. He grew up on a large ranch near the small town of Mazamitla in Jalisco.[17] He obtained a degree in civil engineering in 1925, then spent the following two years in Europe.[18] Here he came in contact with the landscaping work of Ferdinan Bac.[4] When he returned to Mexico, he began building houses in Guadalajara, a number of which became featured in publications in the United States and Italy. In 1936, he moved to Mexico City. Here he worked in real estate development including area in which his house is found today. During his career, he developed projects in Mexico City, Manzanillo, Guadalajara, Acapulco, La Jolla, CA but his best known work is that on Ciudad Satélite. His architecture work is generally confined to houses with his abilities mostly self-taught. In 1976, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held an exhibition of his work and he also received the Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes. In 1980, he received the Pritzker Prize .[7][18] Soon after, he developed Parkinson's disease which impeded his ability to work. He also received two other awards, the Premio Jalisco and the Premio Nacional de Arquitectura before his death, as well as a retrospective of his work at the Museo Tamayo de Arte Contemporáneo. Barragán died at his home on November 22, 1988.[17][18]

Barragan's work is notable for its use of traditional materials, rich spaces, broad planar forms and unlike most of his contemporaries, the use of bright colors.[10] It still has strong influence on Mexican architecture, especially housing, making more modern styles difficult to sell.[16][19]

Description

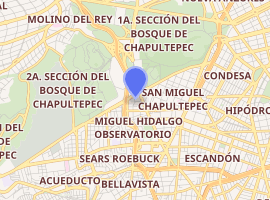

The house is located in Colonia Ampliación Daniel Garza in the Miguel Hidalgo borough of Mexico City.[7] The main facade is on Calle General Francisco Ramírez numbers 12 and 14, a small street near the historic center of the former town of Tacubaya. Today the area is working class, which has been entirely engulfed by the urban sprawl of Mexico City. The Ortega house is next door.[5][6] The house is built from concrete with a plaster rendering.[5] The north end is taken up by the studio, with its own entrance at #12 and the remaining part, number 14, was Barragan's private residence.[5][6] Most of the architectural influence on the house is Mexican but there are also international influences as well.[5] His Mexican influences include the buildings of his youth in Jalisco, the use of masonry building and the tradition of strongly dividing public and private space. His use of color is based on the vibrant colors of traditional Mexico, tempered by the artistic influences of Rufino Tamayo and in particular, Jesús Reyes Ferreira.[6][20] Reyes was influential in moving Mexican interior design away from French to more indigenous looks in the 1930s and 1940s.[17] With the exception of the breakfast nook, the house is designed to not need artificial light during the day, with windows and other openings placed to let in as much light as possible.[6]

The facades of the house align with the street and are very plain, with rough cement walls very similar in color and composition of its neighbors. The only distinction is that the walls are much higher. It has only a few small windows and two doors to the outside streets on the southwest side.[5][6] For this reason the house is not easily visible.[6] Since the facade is plain and flat, there is no way to guess the layout inside.[10] Instead, the house focuses inward, centered on a garden, which itself is surrounded by high walls except on the west. The house has been compared to an oasis with high walls to keep out the “urban chaos.”[16][17]

The qualities of his architecture are expressed in the interior, including the garden space. He used strong non-harmonic color schemes.[5] It is designed for the maximum use of natural light as well as free flowing space, using geometric forms.[11] The total footage of the construction is 1,161m2, with two floors, a roof terrace and a private garden.[4][5] The house represents an integration of modern and traditional architectural styles, which has since been influential, especially in the design of gardens, plazas and landscapes. The levels of the floors are not regular and rooms have different heights.[5]

The main entrance to the studio is at #12 but it can also be accessed from the living room. It can also be accessed from the garden via a patio.[5][6]

After entering the door at #14, one enters a bare and dim foyer, whose main purpose is that of a buffer between the interior of the house and outside world. It is small and sparse. Its flooring is of volcanic stone which continues into the entrance hall. This stone is usually used for exterior floors, giving the area a patio feel.[6] This leads to a vestibule with a high ceiling, yellow light onto a volcanic stone floor and one of the walls painted fuchsia.[10]

Past a low threshold and parchment screen is the living room, with a double height ceiling of wooden beams and a floor of pine planks. The walls are white with small doors leading to service spaces. The main window overlooks the garden.[10] Other spaces on the ground floor include reading room/library, and a dining area, which has a low ceiling and a fuchsia wall with ceramic bowls from all parts of Mexico on display.[10] Areas on this floor are divided by staircases and folding screens.[6]

The dining room, living room, breakfast nook and kitchen all open to the garden area which has a fountain.[5][10] The garden was originally going to be simply grass but the architect allowed a number of plants to grow semi freely, allowing for a more wild feel to the vegetation. It is small but it appears bigger because it borders the neighbor's garden. The windows that face this garden were moved after the building was finished and the marks left by their old sites give this facade an unkempt look. The windows were placed and moved with the interior in mind. One window which was moved was that of the dining room, possibly to correct the view while seated at the table.[6]

Another outside opening is the Patio de las ollas (Patio of the Pots), which is on the west side of the building. It was not in the original plans but was the result of later modifications to separate the workshop from the garden. It is a small space but it provides light and greenery in the center of the structure.[6]

The upper floor is a more private space with thick wood shutters for the windows.[10] Access to this area and the roof terrace is via stone stairs lacking railings, a typical Barragán characteristic.[5][10] The upper floor contains a master bedroom with dressing room, a guest room and an “afternoon room.”[5] The main bedroom has a window facing the garden and was where the architect slept, simply calling it the “white room.” It contains a painting called “Anunciación” as well as a thirty cm tall folding screen with images of an African model which were cut from magazines. The dressing room attached to the bedroom is also called the cuarto del Cristo or Christ room, with its crucifix. The guest room faces east onto the street and originally was a terrace. This and the bedrooms have a monastic feel because of their sparseness and type of furniture, reflecting the Franciscan beliefs of Barragán.[6]

The roof terrace has high walls of blood red, dark brownish gray and white, with the floors in red ceramic tiles. The walls have the effect of framing the sky as well as hiding the chimney, water tank and service stairs. It serves as a small lookout point, overlooking the patio, observatory, chapel and garden. The side facing the garden has a simple wood railing.[6][10]

References

- "Casa Luis Barragán." Secretariat of Culture of Mexico. Retrieved on April 12, 2016. "General Francisco Ramírez 14-16 Col. Ampliación Daniel Garza CP 11840 Miguel Hidalgo, Miguel Hidalgo, Distrito Federal"

- Casa Luis Barragán website Archived 2010-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "Mexico - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Casa Estudio Luis Barragán". Sistema de Información Cultural. Mexico: CONACULTA. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- "Luis Barragán House and Studio". World Heritage Convention. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- "Fachada". Mexico City: Luis Barragán House/Studio. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- "Publican libro "La casa de Luis Barragán"" [Publish book "La casa de Luis Barragán"]. El Economista (in Spanish). Mexico City. February 10, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- "La casa Luis Barragán". Mexico City: Luis Barragán House/Studio. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- Lopez, Maria Luisa (May 31, 1995). "Abriran este ano Casa-Museo Luis Barragan" [Luis Barragán House Museum opens this year]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 12.

- Perez-Gil, Javier (September 1, 2007). "PURSUITS; Leisure & Arts -- Masterpiece: The House Barragan Built; Each room in the late architect's home is a calculated surprise". Wall Street Journal. New York. p. 12.

- "Líneas y luz: la Casa Luis Barragán". Mexico City: Glamour magazine Mexico. January 25, 2013. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- Garcia, Omar (November 2, 2002). "Intervienen artistas Casa Luis Barragan" [Artists intervene at Luis Barragán house]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- Alvarez, Ricardo (January 12, 2000). "Reuniran acervo de Luis Barragan" [Reunite collection of Luis Barragán]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara. p. 1.

- "La Jornada". Jornada.unam.mx. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Exposiciones temporales". Mexico City: Luis Barragán House/Studio. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- "Books And Arts: The colours of serenity; Luis Barragan". The Economist. 366 (8308): 79–80. January 25, 2003.

- Tim Street-Porter (June 1, 1997). "Architecture of Mexico: the houses of Luis Barragan". Mexico City: Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- "Luis Barragán". Mexico City: Luis Barragán House/Studio. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- Barreneche, Raul A (January 1999). "Suburban sophisticate: The AIA Journal The AIA Journal". Architecture. 88 (1): 100–105.

- Canizaro, Vincent B. (2007). Architectural Regionalism : Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity, and Tradition. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 77. ISBN 9781568986166.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Luis Barragán House and Studio. |