Yagul

Yagul is an archaeological site and former city-state associated with the Zapotec civilization of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, located in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. The site was declared one of the country's four Natural Monuments on 13 October 1998.[1] The site is also known locally as Pueblo Viejo (Old Village) and was occupied at the time of the Spanish Conquest. After the Conquest the population was relocated to the nearby modern town of Tlacolula where their descendants still live.[2][3]

| Yagul | |

|---|---|

IUCN category III (natural monument or feature) | |

| |

| |

| Location | Oaxaca, Mexico |

| Nearest city | Tlacolula de Matamoros |

| Coordinates | 16°57′30″N 96°27′1″W |

| Area | 1,076 hectares (2,658.9 acres) |

| Established | May 24, 1999 |

| Governing body | Comision Nacional de Areas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP) |

| Part of | Prehistoric Caves of Yagul and Mitla in the Central Valley of Oaxaca |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iii) |

| Reference | 1352 |

| Inscription | 2010 (34th session) |

Yagul was first occupied around 500-100 BC. Around 500-700 AD, residential, civic and ceremonial structures were built at the site. However, most of the visible remains date to 1250-1521 AD, when the site functioned as the capital of a Postclassic city-state.[4]

The site was excavated in the 1950s and 60s by archaeologists Ignacio Bernal and John Paddock.[2][5]

Vestiges of human habitation in the area, namely cliff paintings at Caballito Blanco, date to at least 3000 BC. After the abandonment of Monte Albán about 800 AD, the region's inhabitants established themselves in various small centers such as Lambityeco, Mitla and Yagul.[1]

Etymology

Yagul comes from the Zapotec language, it is formed from ya (tree) and gul (old), hence "old tree".[1][2]

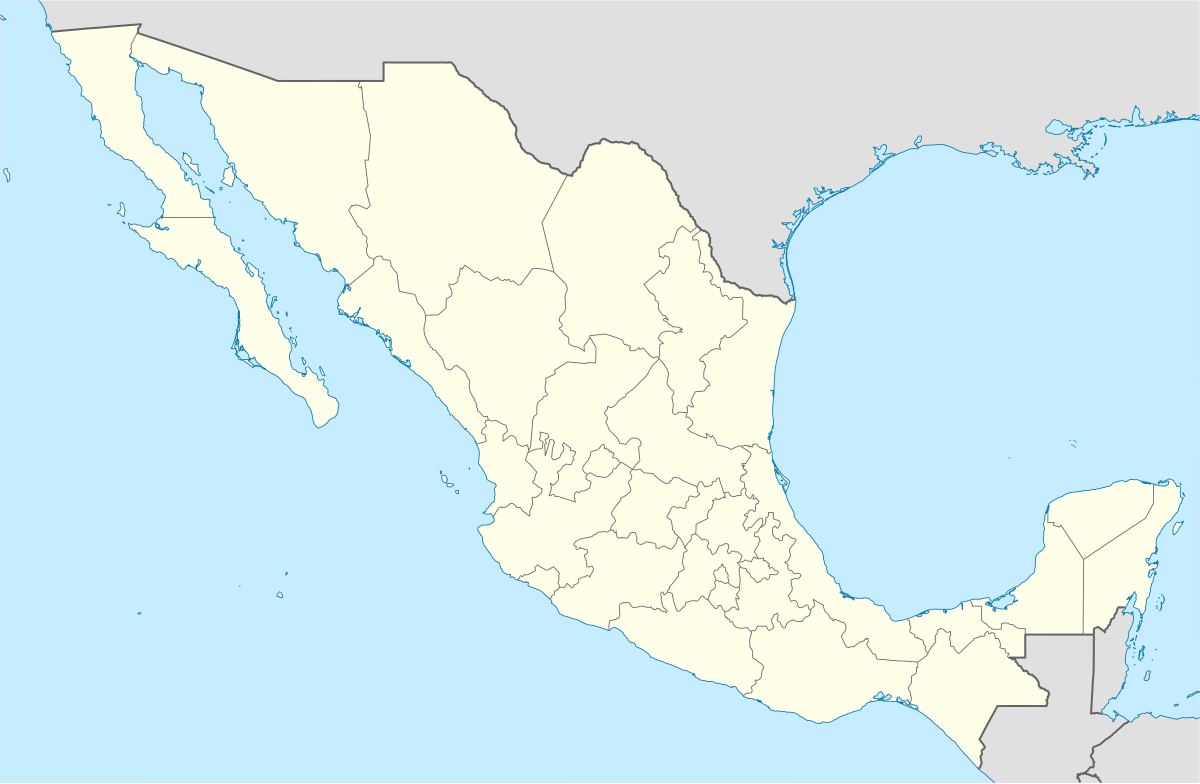

Location

Yagul is located just off Highway 190 between the city of Oaxaca and Mitla, about 36 km from the former.[1] The site is situated on a volcanic outcrop surrounded by fertile alluvial land,[2] in the Tlacolula arm of the Valley of Oaxaca.[6] The Salado river flows to the south.[2]

Site history

Occupation at Yagul dates as far back as the Middle to Late Preclassic. Elaborate Preclassic period burials have been excavated at Yagul, accompanied by ceramic effigy vessels that indicate the increasing influence of Monte Albán upon the local elite.[7]

In the Late Postclassic, immediately prior to the Spanish Conquest, Yagul had a population of more than 6000 people.[8]

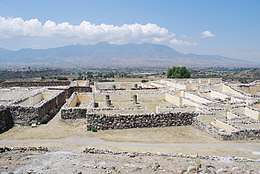

Site description

Yagul is one of the most studied archaeological sites in the Valley of Oaxaca.[8] This important prehispanic centers name literally means "Old Stick" or "Old Tree", The site is set around a hill, and can be divided into three principal areas; the fortress, the ceremonial center and the residential areas.[9] The construction stone at Yagul is mainly river cobbles formed from volcanic rock such as basalt.[2] About 30 tombs have been found at Yagul, sometimes located in pairs. A few of these bear hieroglyphic inscriptions.[10]

Fortress

Situated atop the cliffs to the northeast of the site and protected by natural and artificial walls, it has an excellent vantage point over the whole Tlacolula Valley.[11] It has several lookout points, including one reached by a narrow bridge.[1]

Residential area

Unexcavated residential areas lie on terraces to the south, east and west of the hill.[1] Classic Period residences are to the northwest of the excavated ceremonial centre and lower class Postclassic residences are presumed to lie around the site core.[11]

Ceremonial center

The ceremonial center was excavated in 1974 by Bernal and Gamio.[12] It composes the vast majority of what has been excavated, and what can be seen today. The ceremonial center consists of a number of large patios bordered by monumental architecture, and also includes a ballcourt and an elite residential complex.[12] Some of the structures in this area are:

- Ballcourt. The restored ballcourt has an east–west orientation and is the largest in the Valley of Oaxaca. A carved serpent's head, now in the Regional Museum in Oaxaca, was found fixed to the top of the south wall.[2][13] The ballcourt was built in the Classic Period between 500 and 700 AD, and then widened between 700 and 900 AD.[1] It has a total length of 47 meters and a central field length of 30 meters, and is 6 meters wide.[14]

- Palace of the Six Patios. This is a labyrinthine structure formed of an intricate complex of passageways and many rooms. It is formed of three elite complexes, each with two patios surrounded by rooms. In each pair of patios, the northern was probably a residence and the southern was possibly the administrative area. A tomb entrance is found in each patio.[1] The same layout is found at the nearby site of Mitla although the two sites were probably independent.[2] The walls are faced with dressed stones and stucco over a rough stone and clay core, the floors were of red stucco.[15] Patio F is somewhat different from the others in the complex in that it opened out onto the ballcourt and lower patio complexes and appears to have had a more public function. It had a low bench situated within a room that would have been visible to the areas below and may have been intended for the reception of visitors.[12] The palace complex also included a temple.[16]

- Patio 1 is a large open area immediately southeast of the Palace of the Six Patios. It has rooms on all sides except the south side. Immediately to the south of Patio 1 is a temple.[2]

- Patio 4 lies to the southeast of the ballcourt and is part of a temple-patio-altar complex formed from four mounds around a central altar. It was in use from at least the Classic Period through to the Postclassic. A sculpture of a frog-effigy lies at the base of the eastern mound.[2]

- Tomb 30. This Postclassic tomb lies underneath Patio 4. It is formed of three chambers with decorated panels, the principal chamber has a facade decorated with two human heads carved in stone. The door to the tomb is a stone slab with hieroglyphic inscriptions on both sides.[9][11]

- Council Chamber. This is a long, narrow chamber with an east–west orientation, lying to the south of a narrow "street". It was once decorated with stone mosaics and was entered via steps from Patio 1, which lies immediately to the south. The entrance is divided into 3 sections by two 2-meter wide pillars. Due to its non-residential nature and its lack of a shrine or temple, this room is presumed to have been administrative in function.[1][17]

- Decorated Street. This narrow "street" runs in an east–west direction between the Palace of the Six Patios to the north and the Council Chamber to the south. Its southern wall is over 40 meters long and was decorated with geometric stone mosaics similar to those at Mitla.[1]

- Building U. This building was built on an artificial platform in the northern part of the site, a tomb lies under its floor. It is reached by a stairway to the south and has a good view across most of the site.[1]

The site is in the care of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (National Institute of Anthropology and History) and is open to the public.

Notes

- Yagul at INAH (in Spanish)

- Winter 1998, p.119.

- Adams 1996, p.333.

- Winter 1998, pp.72, 75.

- Winter 1998, p.6.

- Joyce 2010, pp.271-272.

- Joyce 2010, p.147.

- Joyce 2010, p.271.

- INAH 1973, p.38.

- INAH 1973, pp.38, 40.

- Winter 1998, p.120.

- Joyce 2010, p.272.

- INAH 1973, pp.38-39.

- Kowalewski et al. 1991, p.29

- INAH 1973, p.39.

- Joyce 2010, p.273.

- INAH 1973, p.40.

References

- Adams, Richard E.W. (1996). Prehistoric Mesoamerica (Revised ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2834-8. OCLC 22593466.

- INAH [Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia] (1973). The Oaxaca Valley: Official Guide (5th ed.). México, D.F.: INAH. OCLC 1336526.

- Joyce, Arthur A. (2010). Mixtecs, Zapotecs, and Chatinos: Ancient Peoples of Southern Mexico. Chichester, West Sussex, UK.: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20978-2. OCLC 318057918.

- Kowalewski, Stephen A.; Gary M. Feinman; Laura Finsten; Richard E. Blanton (1991). "Pre-Hispanic Ballcourts from the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1360-0. OCLC 51873028.

- Winter, Marcus (1998). Oaxaca: The Archaeological Record. Indian peoples of Mexico series. Alberto Beltrán (illus.) (2nd ed.). México, D.F.: Minutiae Mexicana. ISBN 968-7074-31-0. OCLC 26752490.

External links

- Yagul at INAH (in Spanish)