Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori (/ˈdiːəs/[1] or /ˈdiːæz/; Spanish: [poɾˈfiɾjo ði.as]; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915) was a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico, a total of 31 years, from 17 February 1877 to 1 December 1880 and from 1 December 1884 to 25 May 1911. The entire period 1876–1911 is often referred to as the Porfiriato.[2]

Porfirio Díaz | |

|---|---|

| |

| 29th President of Mexico | |

| In office 1 December 1884 – 25 May 1911 | |

| Vice President | Ramón Corral |

| Preceded by | Manuel González Flores |

| Succeeded by | Francisco León de la Barra |

| In office 17 February 1877 – 1 December 1880 | |

| Preceded by | Juan N. Méndez |

| Succeeded by | Manuel González Flores |

| In office 28 November 1876 – 6 December 1876 | |

| Preceded by | José María Iglesias |

| Succeeded by | Juan N. Méndez |

| Governor of Oaxaca | |

| In office 1 December 1882 – 3 January 1883 | |

| Preceded by | José Mariano Jiménez |

| Succeeded by | José Mariano Jiménez |

| Secretary of Development, Colonization and Industry of Mexico | |

| In office 1 December 1880 – 27 June 1881 | |

| President | Manuel González Flores |

| Preceded by | Vicente Riva Palacio |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Pacheco Villalobos |

| Governor of the Federal District | |

| In office 15 June 1867 – 14 August 1867 | |

| Preceded by | Tomas O'Horan |

| Succeeded by | Juan José Baz |

| Personal details | |

| Born | José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz 15 September 1830 Oaxaca City, Oaxaca, Mexico |

| Died | 2 July 1915 (aged 84) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Cimetière du Montparnasse, Paris |

| Political party | Liberal Party |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Deodato Lucas Porfirio (1875–46) Luz Aurora Victoria (1875–65) |

| Parents | José Faustino Díaz María Petrona Mori |

| Profession | Military officer, politician. |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1848–1876 |

| Rank | General |

A veteran of the War of the Reform (1858–60) and the French intervention in Mexico (1862–67), Díaz rose to the rank of General, leading republican troops against the French-imposed rule of Emperor Maximilian. He subsequently revolted against presidents Benito Juárez and Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, on the principle of no re-election to the presidency. Diaz succeeded in seizing power, ousting Lerdo in a coup in 1876, with the help of his political supporters, and Diaz was elected in 1877. In 1880, he stepped down and his political ally Manuel González was elected president, serving from 1880 to 1884. In 1884 Diaz abandoned the idea of no re-election and held office continuously until 1911.[3]

Díaz has been a controversial figure in Mexican history. His regime brought "order and progress", ending political turmoil and promoting economic development. Díaz and his allies comprised a group of technocrats known as Científicos, "scientists".[4] His economic policies largely benefited his circle of allies as well as foreign investors, and helped a few wealthy estate-owning hacendados acquire huge areas of land, leaving rural campesinos unable to make a living. In later years, these policies grew unpopular due to civil repression and political conflicts, as well as challenges from labor and the peasantry, groups that did not share in Mexico's prosperity.

Despite public statements in 1908 favoring a return to democracy and not running again for office, Díaz reversed himself and ran again in 1910. His failure to institutionalize presidential succession, since he was by then 80 years old, triggered a political crisis between the Científicos and the followers of General Bernardo Reyes, allied with the military and with peripheral regions of Mexico.[5] After Díaz declared himself the winner of an eighth term in office in 1910, his electoral opponent, wealthy estate owner Francisco I. Madero, issued the Plan of San Luis Potosí calling for armed rebellion against Díaz, leading to the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution. After the Federal Army suffered a number of military defeats against the forces supporting Madero, Díaz was forced to resign in May 1911 and went into exile in Paris, where he died four years later.

Early years

Porfirio Díaz was the sixth of seven children, baptized on 15 September 1830, in Oaxaca, Mexico, but his actual date of birth is unknown.[6] 15 September is an important date in Mexican history, the eve of the day when hero of independence Miguel Hidalgo issued his call for independence in 1810; when Díaz became president, the independence anniversary was commemorated on 15 September rather than on the 16th, a practice that continues to the present era.[7] Díaz was a castizo.[8] Díaz's father, José Díaz, was a Criollo (a Mexican of predominantly Spanish ancestry).[8][9][10] His mother, Petrona Mori (or Mory), was a Mestizo woman, daughter of a man of predominantly Spanish ancestry and an indigenous woman named Tecla Cortés; There is confusion about Jose Diaz's full name, which is listed on the baptismal certificate as José de la Cruz Díaz; he was also known as José Faustino Díaz, and was a modest innkeeper who died of cholera when his son was three.[8][9]

Despite the family's difficult economic circumstances following Díaz's father's death in 1833, Díaz was sent to school at the age of 6.[11] In the early independence period, the choice of professions was narrow: lawyer, priest, physician, military. The Díaz family was devoutly religious, and Díaz began training for the priesthood at the age of fifteen when his mother, María Petrona Mori Cortés, sent him to the Colegio Seminario Conciliar de Oaxaca. He was offered a post as a priest in 1846, but national events intervened. Díaz joined with seminary students who volunteered as soldiers to repel the U.S. invasion during the Mexican–American War, and, despite not seeing action, decided his future was in the military, not the priesthood.[11] Also in 1846, Díaz came into contact with a leading Oaxaca liberal, Marcos Pérez, who taught at the secular Institute of Arts and Sciences in Oaxaca. That same year, Díaz met Benito Juárez, who became governor of Oaxaca in 1847, a former student there.[12] In 1849, over the objections of his family, Díaz abandoned his ecclesiastical career and entered the Instituto de Ciencias and studied law.[9][12] When Antonio López de Santa Anna was returned to power by a coup d'état in 1853, he suspended the 1824 constitution and began persecuting liberals. At this point, Díaz had already aligned himself with radical liberals (rojos), such as Benito Juárez. Juárez was forced into exile in New Orleans; Díaz supported the liberal Plan de Ayutla that called for the ouster of Santa Anna. Díaz evaded an arrest warrant and fled to the mountains of northern Oaxaca, where he joined the rebellion of Juan Álvarez.[13] In 1855, Díaz joined a band of liberal guerrillas who were fighting Santa Anna's government. After the ousting and exile of Santa Anna, Díaz was rewarded with a post in Ixtlán, Oaxaca, that gave him valuable practical experience as an administrator.

Military career

Díaz's military career is most notable for his service in the struggle against the French. By the time of the Battle of Puebla (5 May 1862), Mexico's great victory over the French when they first invaded, Díaz had advanced to the rank of general and was placed in command of an infantry brigade.[9][14]

During the Battle of Puebla, his brigade was positioned centered between the forts of Loreto and Guadalupe. From there, he successfully helped repel a French infantry attack meant as a diversion, to distract the Mexican commanders' attention from the forts that were the French army's main targets. In violation of General Ignacio Zaragoza's orders, after helping fight off the larger French force, Díaz and his unit then pursued them and later Zaragoza commended his actions during the battle as "brave and notable".

In 1863, Díaz was captured by the French Army. He escaped and President Benito Juárez offered him the positions of secretary of defense or army commander in chief. He declined both, but took an appointment as commander of the Central Army. That same year, he was promoted to the position of Division General.

In 1864, the conservatives supporting Emperor Maximilian asked him to join the Imperial cause. Díaz declined the offer. In 1865, he was captured by the Imperial forces in Oaxaca. He escaped and fought the battles of Tehuitzingo, Piaxtla, Tulcingo and Comitlipa.

In 1866, Díaz formally declared loyalty. That same year, he earned victories in Nochixtlán, Miahuatlán, and La Carbonera, and once again captured Oaxaca destroying most French gains in the south of the country. He was then promoted to general. Also in 1866, Marshal Bazaine, commander of the Imperial forces, offered to surrender Mexico City to Díaz if he withdrew support of Juárez. Díaz declined the offer. In 1867, Emperor Maximilian offered Díaz the command of the army and the imperial rendition to the liberal cause. Díaz refused both. Finally, on 2 April 1867, he went on to win the final battle for Puebla. By the end of the war, he was hailed as a national hero.

Early opposition political career

When Juárez became the president of Mexico in 1868 and began to restore peace, Díaz resigned his military command and went home to Oaxaca. However, it was not long before Díaz was openly opposed to the Juárez administration, since Juárez held onto the presidency. As a Liberal military hero, Díaz had ambitions for national political power. He challenged the civilian Juárez, who was running for what Díaz considered an illegal subsequent term as president. In 1870, Díaz ran against President Juárez and Vice President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada. The following year, Díaz made claims of fraud in the July elections won by Juárez, who was confirmed as president by the Congress in October. In response, Díaz launched the Plan de la Noria on 8 November 1871, supported by a number of rebellions across the nation, including one by General Manuel González of Tamaulipas, but this rebellion failed.[15] In March 1872, Díaz's forces were defeated in the battle of La Bufa in Zacatecas.

Following the death of Juárez of natural causes on 9 July 1872, Lerdo became president. With Juárez's death, Díaz's principle of no re-election could not be used to oppose Lerdo, a civilian like Juárez. Lerdo offered amnesty to the rebels, which Díaz accepted and "retired" to the Hacienda de la Candelaria in Tlacotalpan, Veracruz, rather than his home state of Oaxaca.[15] In 1874, Díaz was elected to Congress from Veracruz. Opposition to Lerdo grew, particularly as his militant anti-clericalism increased, labor unrest grew, and a major rebellion of the Yaqui in northwest Mexico under the leadership of Cajemé challenged central government rule there.[16] Díaz saw an opportunity to plot a more successful rebellion, leaving Mexico in 1875 for New Orleans and Brownsville, Texas, with his political ally, fellow general Manuel González. Although Lerdo offered Díaz an ambassadorship in Europe, a way to remove him from the Mexican political scene, Díaz refused. With Lerdo running for a term of his own, Díaz could again invoke the principle of no re-election as a reason to revolt.

Becoming president and first term, 1876–80

Diaz launched his rebellion in Ojitlan, Oaxaca, on 10 January 1876 under the Plan of Tuxtepec, which initially failed. Díaz fled to the United States.[9] Lerdo was re-elected in July 1876 and his constitutional government was recognized by the United States. Díaz returned to Mexico and fought the Battle of Tecoac, where he defeated Lerdo's forces in what turned out to be the last battle (on 16 November).[9] In November 1876, Díaz occupied Mexico City, and Lerdo left Mexico for exile in New York. Díaz did not take formal control of the presidency until the beginning of 1877, putting in General Juan N. Méndez as provisional president, followed by new presidential elections in 1877 that gave Díaz the presidency. Ironically, one of his government's first amendments to the liberal 1857 constitution was to prevent re-election.[17]

Although the new election gave some air of legitimacy to Diaz's government, the United States did not recognize the regime. It was not clear that Díaz would continue to prevail against supporters of ousted President Lerdo, who continued to challenge Díaz's regime by insurrections, which ultimately failed. In addition, cross-border Apache attacks with raids on one side and sanctuary on the other was a sticking point.[18] Mexico needed to meet several conditions before the U.S. would consider recognizing Díaz's government, including payment of a debt to the U.S. and restraining the cross-border Apache raids. The U.S. emissary to Mexico, John W. Foster, had the duty to protect the interests of the U.S. first and foremost. Lerdo's government had entered into negotiations with the U.S. over claims that each had against the other in previous conflicts. A joint U.S.-Mexico Claims Commission was established in 1868, in the wake of the fall of the French Empire.[19] When Díaz seized power from Lerdo's government, he inherited Lerdo's negotiated settlement with the U.S. As Mexican historian Daniel Cosío Villegas put it, "He Who Wins Pays."[20] Díaz secured recognition by paying $300,000 to settle claims by the U.S. In 1878, the U.S. government recognized the Díaz regime and former U.S. president and Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant visited Mexico.[21]

During his first term in office, Díaz developed a pragmatic and personalist approach to solve political conflicts. Although a political liberal who had stood with radical liberals in Oaxaca (rojos), he was not a liberal ideologue, preferring pragmatic approaches towards political issues. He was explicit about his pragmatism. He maintained control through generous patronage to political allies.[22] In his first term, members of his political alliance were discontented that they had not sufficiently benefited from political and financial rewards. In general he sought conciliation, but force could be an option. "'Five fingers or five bullets,' as he was fond of saying."[23] Although he was an authoritarian ruler, he maintained the structure of elections, so that there was the façade of liberal democracy. His administration became famous for suppression of civil society and public revolts. One of the catch phrases of his later terms in office was the choice between "pan o palo", ("bread or the bludgeon")—that is, "benevolence or repression."[24] Díaz saw his task in his term as president to create internal order so that economic development could be possible. As a military hero and astute politician, Díaz's eventual successful establishment of that peace (Paz Porfiriana) became "one of [Díaz's] principal achievements, and it became the main justification for successive re-elections after 1884."[25]

Díaz and his advisers' pragmatism in relation to the United States became the policy of "defensive modernization", which attempted to make the best of Mexico's weak position against its northern neighbor. Attributed to Díaz was the phrase "so far from God, so close to the United States." Díaz's advisers Matías Romero, Juárez's emissary to the U.S., and Manuel Zamacona, a minister in Juárez's government, advised a policy of "peaceful invasion" of U.S. capital to Mexico, with the expectation that it would then be "naturalized" in Mexico. In their view, such an arrangement would "provide 'all possible advantages of annexation without ....its inconveniences'."[26] Díaz was won over to that viewpoint, which promoted Mexican economic development and gave the U.S. an outlet for its capital and allowed for its influence in Mexico. By 1880, Mexico was forging a new relationship with the U.S. as Díaz's term of office was ending.

González presidency, 1880–84

Díaz stepped down from the presidency, with his ally, General Manuel González, one of the trustworthy members of his political network (camarilla), elected president in a fully constitutional manner.[9] This four-year period, often characterized as the "González Interregnum,"[27] is sometimes seen as Díaz placing a puppet in the presidency, but González ruled in his own right and was viewed as a legitimate president free of the taint of coming to power by coup. During this period, Díaz briefly served as governor of his home state of Oaxaca. He also devoted time to his personal life, highlighted by his marriage to Carmen Romero Rubio, the devout 17-year-old daughter of Manuel Romero Rubio, a supporter of Lerdo. The couple honeymooned in the U.S., going to the New Orleans World's Fair, St. Louis, Washington, D.C. and New York. Accompanying them on their travels was Matías Romero and his U.S.-born wife. This working honeymoon allowed Díaz to forge personal connections with politicians and powerful businessmen with Romero's friends, including former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant. Romero then publicized the growing amity between the two countries and the safety of Mexico for U.S. investors.[28]

President González was making room in his government for political networks not originally part of Díaz's coalition, some of whom had been loyalists to Lerdo, including Evaristo Madero, whose grandson Francisco would challenge Díaz for the presidency in 1910. Important legislation changing rights to land and subsoil rights, and to encourage immigration and colonization by U.S. nations was passed during the González presidency. The administration also extended lucrative railway concessions to U.S. investors. Despite those developments, the González administration met financial and political difficulties, with the later period bringing the government to bankruptcy and popular opposition. Díaz's father-in-law Manuel Romero Rubio linked these issues to personal corruption by González. Despite Díaz's previous protestations of "no re-election", he ran for a second term in the 1884 elections.[29]

During this period the Mexican underground political newspapers spread the new ironic slogan for the Porfirian times, based on the slogan "Sufragio Efectivo, No Reelección" (Effective suffrage, no re-election) and changed it to its opposite, "Sufragio Efectivo No, Reelección" (Effective suffrage – No. Re-election!).[30] Díaz had the constitution amended, first to allow two terms in office, and then to remove all restrictions on re-election. With these changes in place, Díaz was re-elected four more times by implausibly high margins, and on some occasions claimed to have won with either unanimous or near-unanimous support.[30]

Over the next twenty-six years as president, Díaz created a systematic and methodical regime with a staunch military mindset.[9] His first goal was to establish peace throughout Mexico. According to John A. Crow, Díaz "set out to establish a good strong paz porfiriana, or Porfirian peace, of such scope and firmness that it would redeem the country in the eyes of the world for its sixty-five years of revolution and anarchy" since independence.[31] His second goal was outlined in his motto – "little of politics and plenty of administration,"[31] meaning the eliminating open political conflict replaced by a well-functioning government apparatus.

Administration 1884–1896

To secure his power, Díaz engaged in various forms of co-optation and coercion. He constantly balanced between the private desires of different interest groups and playing off one interest against another.[9] Following the González presidency, Díaz abandoned favoring his own political group (camarilla) that brought him to power in 1876 in the Plan of Tuxtepec and selected ministers and other high officials from other factions. Those included those loyal to Juárez (Matías Romero) and Lerdo (Manuel Romero Rubio). (Manuel Dublán) was one of the few loyalists from the Plan of Tuxtepec that Diaz retained as a cabinet minister. As money flowed to the Mexican treasury from foreign investments, Díaz could buy off his loyalists from Tuxtepec. An important group supporting the regime were foreign investors, especially from the U.S. and Great Britain, as well as Germany and France. Díaz himself met with investors, binding him with this group in a personal rather than institutional fashion.[32] The close cooperation between these foreign elements and the Díaz regime was a key nationalist issue in the Mexican Revolution.

In order to satisfy any competing domestic forces, such as the mixed-race Mestizos and wealthier indigenous leaders, Díaz gave them political positions that they could not refuse or made them intermediators for foreign interests, enriching them. He did the same thing with elite society by not interfering with their wealth and haciendas. The urban middle classes in Mexico City were often in opposition to the government, but with the country's economic prosperity and the expansion of the government, they had job opportunities in federal employment.[33]

Covering both pro- and anti-clerical elements, Díaz was both the head of the Freemasons in Mexico and an important advisor to the Catholic bishops.[34] Díaz proved to be a different kind of liberal than those of the past. He neither assaulted the Church (like most liberals) nor protected the Church.[35] With the influx of foreign investment and investors, Protestant missionaries arrived in Mexico, especially in Mexico's north, and Protestants became an opposition force during the Mexican Revolution.[36]

Although there was factionalism in the ruling group and in some regions, Díaz suppressed the formation of opposition parties.[37] Díaz dissolved all local authorities and all aspects of federalism that once existed. Not long after he became president, the governors of all federal states in Mexico answered directly to him.[9] Those who held high positions of power, such as members of the legislature, were almost entirely his closest and most loyal friends. Congress was a rubber stamp for his policy plans and they were compliant in amending the 1857 constitution to allow his re-election and extension of the presidential term.[38] In his quest for even more political control, Díaz suppressed the press and controlled the court system.[9]Díaz could intervene in political matters that threatened political stability, such as in the conflict in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila, placing José María Garza Galan in the governorship, undercutting wealthy estate owner Evaristo Madero, grandfather of Francisco I. Madero, who would challenge Díaz in the 1910 election. In another case, Díaz placed General Bernardo Reyes in the governorship of the state of Nuevo León, displacing existing political elites, but they made do, becoming wealthy during the Porfiriato.[39]

A key supporter of Díaz was former Lerdista Manuel Romero Rubio. According to historian Friedrich Katz, "Romero Rubio was in many respects the architect of the Porfirian state."[40] The relationship between the two was cemented when Díaz married Romero Rubio's young daughter, Carmen. Romero Rubio and his supporters did not oppose the amendment to the Constitution to allow Díaz's initial re-election and then indefinite re-election. One of Romero Rubio's protégés was José Yves Limantour, who became the main financial adviser to the regime, stabilizing the country's public finances. Limantour's political network was dubbed the Científicos, "the scientists", for their approach to governance. They sought reforms, such as decreasing corruption and increasing uniform application of laws. Díaz opposed any significant reform and continued to appoint governors and legislators and control the judiciary.

A potential opposition force was the Mexican Federal Army. Troops were often men forced into military service and poorly paid. Díaz increased the size of the military budget and began modernizing the institution along the lines of European militaries, including the establishment of a military academy to train officers. High rank officers were brought into government service.[41] Diaz expanded the crack police force, the Rurales, who were under control of the president.[42] Díaz knew that it was crucial for him to suppress banditry; he expanded the Rurales, although it guarded chiefly only transport routes to major cities.[43] Díaz thus worked to enhance his control over the military and the police.[35]

Economic development under Díaz

Díaz sought to attract foreign investment to Mexico to aid development of mining, agriculture, industry, and infrastructure. Political stability and the revision of laws, some dating to the colonial era, created a legal structure and an atmosphere where entrepreneurs felt secure in investing capital in Mexico. Railways, financed by foreign capital, transformed areas that were remote from markets into productive regions. The government mandate to survey land meant that secure title was established for investors. The process often obliterated claims of local communities that could not prove title or extinguished traditional usage of forests and other areas not under cultivation. The private survey companies bid for contracts from the Mexican government, with the companies acquiring one-third of the land measured, often prime land that was along proposed railway routes. Companies usually sold that land, often to foreigners who pursued large-scale cultivation of crops for export.[44] Crops included coffee, rubber, henequen (for twine used in binding wheat), sugar, wheat, and vegetable production. Land only suitable for pasturage was enclosed with barbed wire, extinguishing traditional communal grazing of cattle, and premium cattle were imported. Owners of large landed estates (haciendas) often took the opportunity to sell to foreign investors as well. The result by the turn of the twentieth century was the transfer of a vast amount of Mexican land in all parts of the country into foreign hands, either individuals or land companies. Along the northern border with the U.S., American investors were prominent, but they owned land along both coasts, across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and central Mexico.[45] Rural communities and small-scale farmers lost their holdings and forced to be agricultural wage laborers or pursue or move. Conditions on haciendas were often harsh.[46] Landlessness caused rural discontent and a major cause of peasant participation in the Mexican Revolution, seeking a reversal of the concentration of land ownership through land reform.

For elites, "it was the golden age of Mexican economics, 3.2 dollars per peso. Mexico was compared economically to economic powers of the time such as France, Great Britain, and Germany. For some Mexicans, there was no money and the doors were thrown open to those who had."[31] Economic progress varied drastically from region to region. The north was defined by mining and ranching while the central valley became the home of large-scale farms for wheat and grain and large industrial centers.[35]

One component of economic growth involved stimulating foreign investment in the Mexican mining sector. Through tax waivers and other incentives, investment and growth were effectively realized. The desolate region of Baja California Sur benefited from the establishment of an economic zone with the founding of the town of Santa Rosalía and the commercial development of the El Boleo copper mine. This came about when Díaz granted a French mining company a 70-year tax waiver in return for its substantial investment in the project. In a similar fashion, the city of Guanajuato realized substantial foreign investment in local silver mining ventures. The city subsequently experienced a period of prosperity, symbolized by the construction of numerous landmark buildings, most notably, the magnificent Juárez Theatre. By 1900 over 90% of the communal land of the Central Plateau had been sold off or expropriated, forcing 9.5 million peasants off the land and into service of big landowners.[47]

Because Díaz had created such an effective centralized government, he was able to concentrate decision-making and maintain control over the economic instability.[35] This instability arose largely as a result of the dispossession of hundreds of thousands of peasants of their land. Communal indigenous landholdings were privatized, subdivided, and sold. The Porfiriato thus generated a stark contrast between rapid economic growth and sudden, severe impoverishment of the rural masses, a situation that was to explode in the Mexican revolution of 1910.[48]

During 1883–1894, laws were passed to give fewer and fewer people large amounts of land, which was taken away from people by bribing local judges to declare it vacant or unoccupied (terrenos baldíos). A friend of Díaz obtained 12 million acres of land in Baja California by bribing local judges. Those who opposed were killed or captured and sold as slaves to plantations. The manufacture of cheap alcohol increased prompting the number of bars in Mexico City to rise from 51 in 1864 to 1,400 in 1900. This caused the rate of death from alcoholism and alcohol related accidents to rise to levels higher than anywhere else in the world.[49]

Relations with the Catholic Church

Unlike many doctrinaire liberals, Díaz was not virulently anti-clerical. Radical liberalism was anti-clerical, seeing the privileges of the Church as challenging the idea of equality before the law and individual, rather than corporate identity. The economic power of the Church was considered a detriment to modernization and development. The Church as a major corporate landowner and de facto banking institution shaped investments to conservative landed estates more than industry, infrastructure building, or exports.

However, powerful liberals implemented legal measures to curtail the power of the Church. The Juárez Law abolished special privileges (fueros) of ecclesiastics and the military, and the Lerdo law mandated disentailment of the property of corporations, specifically the Church and indigenous communities. The liberal constitution of 1857 removed the privileged position of the Catholic Church and opened the way to religious toleration, considering religious expression as freedom of speech. However, Catholic priests were ineligible for elective office, but could vote.[50] Conservatives fought back in the War of the Reform, under the banner of religión y fueros (that is, Catholicism and special privileges of corporate groups), but they were defeated in 1861.

Following the fall of the Second Empire in 1867, liberal presidents Benito Juárez and his successor Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada began implementing the anti-clerical measures of the constitution. Lerdo went further, extending the laws of the Reform to formalize: separation of Church and State; civil marriage as the only valid manner for State recognition; prohibitions of religious corporations to acquire real estate; elimination from legal oaths any religious element, but only a declaration to tell the truth; and the elimination of monastic vows as legally binding.[51] Further prohibitions on the Church in 1874 included: the exclusion of religion in public institutions; restriction of religious acts to church precincts; banning of religious garb in public except within churches; and prohibition of the ringing of church bells except to summon parishioners.[52]

Díaz was a political pragmatist and not an ideologue, likely seeing that the religious question re-opened political discord in Mexico. When he rebelled against Lerdo, Díaz had at least the tacit and perhaps even the explicit support of the Church.[53] When he came to power in 1877, Díaz left the anti-clerical laws in place, but no longer enforced them as state policy, leaving that to individual Mexican states. This led to the re-emergence of the Church in many areas, but in others a less full role. The Church flouted the Reform prohibitions against wearing clerical garb, there were open-air processions and Masses, and religious orders existed.[54] The Church also recovered its property, sometimes through intermediaries, and tithes were again collected.[54] The Church regained its role in education, with the complicity of the Díaz regime which did not put money into public education. The Church also regained its role in running charitable institutions.[55] Despite the increasingly visible role of the Catholic Church during the Porfiriato, the Vatican was unsuccessful in getting the reinstatement of a formal relationship between the papacy and Mexico, and the constitutional limitations of the Church as an institution remained the law of the land.[56]

This modus vivendi between Díaz and the Church had pragmatic and positive consequences. Díaz did not publicly renounce liberal anti-clericalism, meaning that the Constitution of 1857 remained in place, but he did not enforce its anti-clerical measures. Conflict could reignite, but it was to the advantage of both Church and the Díaz government for this arrangement to continue. If the Church did counter Díaz, he had the constitutional means to rein in its power. The Church regained considerable economic power, with conservative intermediaries holding lands for it. The Church remained important in education and charitable institutions. Other important symbols of the normalization of religion in late 19th century Mexico included: the return of the Jesuits (expelled by the Bourbon monarchy in 1767); the crowning of the Virgin of Guadalupe as "Queen of Mexico"; and the support of Mexican bishops for Díaz's work as peacemaker.[57] Not surprisingly, when the Mexican Revolution broke out in 1910, the Catholic Church was a staunch supporter of the Díaz regime.[58]

Cracks in the political system

Díaz has been characterized as a "republican monarch and his regime a synthesis of pragmatic [colonial-era] Bourbon methods and Liberal republican ideals.... As much by longevity as by design, Díaz came to embody the nation."[59] Díaz did not plan well for the transition to a regime other than his own. As Diaz aged and continued to be re-elected, the question of presidential succession became more urgent. Political aspirants within his regime envisioned succeeding to the presidency and opponents began organizing in anticipation of Díaz's exit.

In 1898, the Díaz regime faced a number of important issues, with the death of Matías Romero, Díaz's long-time political adviser who had made great efforts to strengthen Mexico's ties with the U.S. since the Juárez regime, and a major shift in U.S. foreign policy toward imperialism with its success in the Spanish–American War. Romero's death created new dynamics amongst the three political groups that Díaz both relied upon and manipulated. Romero's faction had strongly supported U.S. investment in Mexico, and was largely pro-American, but with Romero's death his faction declined in power. The other two factions were José Yves Limantour's Científicos and Bernardo Reyes's followers, the Reyistas. Limantour pursued a policy of offsetting U.S. influence by favoring European investment, especially British banking houses and entrepreneurs, such as Weetman Pearson. U.S. investment in Mexico remained robust, even grew, but the economic climate was more hostile to their interests and their support for the regime declined.[60]

The U.S. had asserted that it had the preeminent role in the Western hemisphere, with U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt modifying the Monroe Doctrine via the Roosevelt Corollary, which declared that the U.S. could intervene in other countries' political affairs if the U.S. determined they were not well run. Díaz pushed back against this policy, saying that the security of the hemisphere was a collective enterprise of all its nations. There was a meeting of American states, in the second Pan-American Conference, which met in Mexico City from 22 October 1901 – 31 January 1902, and the U.S. backed off from its hard-line policy of interventionism, at least for the moment in regard to Mexico.[61]

In domestic politics, Bernardo Reyes became increasingly powerful, and Díaz appointed him Minister of War. The Mexican Federal Army was becoming increasingly ineffective. With wars being waged against the Yaqui in northwest Mexico and the Maya, Reyes requested and received increased funding to augment the number of men at arms.

There was some open opposition to Díaz's regime, with eccentric lawyer Nicolás Zúñiga y Miranda running against Díaz. Zúñiga lost every election but always claimed fraud and considered himself to be the legitimately elected president, but he did not mount a serious challenge to the regime.[62] More importantly, as the 1910 election approached and Díaz stated he would not run for re-election, Limantour and Reyes vied against each other for favor.

On 17 February 1908, in an interview with the U.S. journalist James Creelman of Pearson's Magazine, Díaz stated that Mexico was ready for democracy and elections and that he would retire and allow other candidates to compete for the presidency.[9] Without hesitation, several opposition and pro-government groups united to find suitable candidates who would represent them in the upcoming presidential elections. Many liberals formed clubs supporting Bernardo Reyes, then the governor of Nuevo León, as a candidate. Despite the fact that Reyes never formally announced his candidacy, Díaz continued to perceive him as a threat and sent him on a mission to Europe, so that he was not in the country for the elections.

In 1909, Díaz and William Howard Taft, the then president of the United States, planned a summit in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico, a historic first meeting between a U.S. president and a Mexican president and also the first time an American president would cross the border into Mexico.[63] Díaz requested the meeting to show U.S. support for his planned seventh run as president, and Taft agreed to protect the several billion dollars of American capital then invested in Mexico.[64] After nearly 30 years with Díaz in power, U.S. businesses controlled "nearly 90 percent of Mexico's mineral resources, its national railroad, its oil industry and, increasingly, its land."[65] Both sides agreed that the disputed Chamizal strip connecting El Paso to Ciudad Juárez would be considered neutral territory with no flags present during the summit, but the meeting focused attention on this territory and resulted in assassination threats and other serious security concerns.[66] The Texas Rangers, 4,000 U.S. and Mexican troops, U.S. Secret Service agents, FBI agents and U.S. marshals were all called in to provide security.[67] An additional 250-man private security detail led by Frederick Russell Burnham, the celebrated scout, were hired by John Hays Hammond, a close friend of Taft from Yale and a former candidate for U.S. vice president in 1908 who, along with his business partner Burnham, held considerable mining interests in Mexico.[68][69][70] On 16 October, the day of the summit, Burnham and Private C.R. Moore, a Texas Ranger, discovered a man holding a concealed palm pistol standing at the El Paso Chamber of Commerce building along the procession route.[71] Burnham and Moore captured and disarmed the assassin within only a few feet of Díaz and Taft.[72]

1910 Centennial of Independence

The year 1910 was important in Mexico's history—the centennial of the revolt by Father Miguel Hidalgo that liberals saw as the start of the movement for Mexico's independence. Although Hidalgo was caught and executed in 1811 and it took nearly a decade of fighting to achieve independence, it was former royalist military officer Agustín de Iturbide who made the break with Spain in 1821. On the cover of the official program for the centennial, three figures are shown: Hidalgo, father of independence; Benito Juárez, with the label "Lex" (law); and Porfirio Díaz, with the label "Pax" (peace). Also on the cover are the emblem of Mexico and the cap of liberty. Díaz inaugurated the monument to Independence with its golden angel during the September centennial celebrations. Although Díaz and Juárez had been political rivals after the French Intervention, Díaz had done much to promote the legacy of his dead rival and had a large monument to Juárez built by the Alameda Park, which Díaz inaugurated during the centennial. A work published in 1910 details the day-by-day events of the September festivities.[73]

1910 election

As groups began to settle on their presidential candidate, Díaz decided that he was not going to retire but rather allow Francisco I. Madero, an elite but democratically leaning reformer, to run against him. Although Madero, a landowner, was very similar to Díaz in his ideology, he hoped for other elites in Mexico to rule alongside the president. Ultimately, however, Díaz did not approve of Madero and had him jailed during the 1910 election.

The election went ahead. Madero had gathered much popular support, but when the government announced the official results, Díaz was proclaimed to have been re-elected almost unanimously, with Madero said to have attained a minuscule number of votes. This case of massive electoral fraud aroused widespread anger throughout the Mexican citizenry.[9] Madero called for revolt against Díaz in the Plan of San Luis Potosí, and the violence to oust Díaz is now seen as the first phase of the Mexican Revolution. Díaz was forced to resign from office on 25 May 1911 and left the country for Spain six days later, on 31 May 1911.[74]

Personal life

Díaz came from a devoutly Catholic family; his uncle, José Agustín, was bishop of Oaxaca. Díaz had trained for the priesthood, and it seemed likely that was his career path. Oaxaca was a center of liberalism, and the founding of the Institute of Arts and Sciences, a secular institution, helped foster professional training for Oaxacan liberals, including Benito Juárez and Porfirio Díaz. When Díaz abandoned his ecclesiastical career for one in the military, his powerful uncle disowned him.[75]

In Díaz's personal life, it is clear that religion still mattered and that fierce anti-clericalism could have a high price. In 1870, his brother Félix, a fellow liberal, who was then governor of Oaxaca, had rigorously applied the anti-clerical laws of the Reform. In the rebellious and supposedly idolatrous town of Juchitán in Tehuantepec, Félix Díaz had "roped the image of the patron saint of Juchitán … to his horse and dragged it away, returning the saint days later with its feet cut off".[76] When Félix had to flee Oaxaca City in 1871 following Porfirio's failed coup against Juárez, Félix ended up in Juchitán, where the villagers killed him, doing to his body even worse than he did to their saint.[76] Having lost a brother to the fury of religious peasants, Díaz had a cautionary tale about the dangers of enforcing anti-clericalism. Even so, it is clear that Díaz wanted to remain in good standing with the Church.

Díaz married Delfina Ortega Díaz (1845–1880), the daughter of his sister, Manuela Josefa Díaz Mori (1824–1856). Díaz and his niece would have seven children, with Delfina dying due to complications of her seventh delivery. Following her death, he wrote a private letter to Church officials renouncing the Laws of the Reform, which allowed his wife to be buried with Catholic rites in sacred ground.[77]

Díaz had a relationship with a soldadera, Rafaela Quiñones, during the war of the French Intervention, which resulted in the birth of Amada Díaz (1867–1962) , whom he recognized. Amada went to live in Díaz's home with his wife Delfina.[78] Amada married Ignacio de la Torre y Mier, but the couple had no children. De la Torre was said to have been present at the 1901 Dance of the Forty-One, a gathering of gay men and cross-dressers that was raided by police. The report that de la Torre was there was neither confirmed nor denied, but the dance was a huge scandal at the time, satirized by caricaturist José Guadalupe Posada.

Díaz remarried in 1881, to Carmen Romero Rubio, the pious 17-year-old daughter of his most important advisor, Manuel Romero Rubio. Oaxaca cleric Father Eulogio Gillow y Zavala gave his blessing. Gillow was later appointed archbishop of Oaxaca. Doña Carmen is credited with bringing Díaz into closer reconciliation with the Church, but Díaz was already inclined in that direction.[57] The marriage produced no children, but Díaz's surviving children lived with the couple until adulthood.

Although Díaz is criticized on many grounds, he did not create a family dynasty. His only son to survive to adulthood, Porfirio Díaz Ortega, known as "Porfirito," trained to be an officer at the military academy. He graduated as a military engineer and never served in combat. He and his family went into European exile after Díaz's resignation. They were allowed to return to Mexico during the amnesty of Lázaro Cárdenas.

Díaz kept his brother's son Félix Díaz away from political or military power. He did, however, allow his nephew to enrich himself. It was only after Díaz went into exile in 1911 that his nephew became prominent in politics, as the embodiment of the old regime. Even so, Díaz's assessment of his nephew proved astute since Félix never successfully led troops or garnered sustained support, and was forced into exile several times.[79]

On 2 July 1915, Díaz died in exile in Paris, France. He is buried there in the Cimetière du Montparnasse. He was survived by his second wife (María del Carmen Romero-Rubio Castelló, 1864–1944) and two of his children with his first wife, (Deodato Lucas Porfirio Díaz Ortega, 1873–1946, and Luz Aurora Victoria Díaz Ortega, 1875–1965), as well as his natural daughter Amada. His other children died as infants or young children. His widow Carmen and his son were allowed to return to Mexico.[80]

In 1938, the 430-piece collection of arms of the late General Porfirio Díaz was donated to the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario.[81]

Legacy

The legacy of Díaz has undergone revision since the 1990s. In Díaz's lifetime before his ouster, there was an adulatory literature, which has been named "Porfirismo". The vast literature that characterizes him as a ruthless tyrant and dictator has its origins in the late period of Díaz's rule and has continued to shape Díaz's historical image. In recent years, however, Díaz's legacy has been re-evaluated by Mexican historians, most prominently by Enrique Krauze, in what has been termed "Neo-Porfirismo".[82][83][84] As Mexico pursued a neoliberal path under President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, the modernizing policies of Díaz that opened Mexico up to foreign investment fit with the new pragmatism of the Institutional Revolutionary Party. Díaz was characterized as a far more benign figure for these revisionists.

Díaz is usually credited with the saying, "¡Pobre México! ¡Tan lejos de Dios y tan cerca de los Estados Unidos!" (Poor Mexico, so far from God and so close to the United States!).[85][86]

Partly due to Díaz's lengthy tenure, the current Mexican constitution limits a president to a single six-year term with no possibility of re-election, even if it is nonconsecutive. Additionally, no one who holds the post, even on a caretaker basis, is allowed to run or serve again. This provision is so entrenched that it remained in place even after legislators were allowed to run for a second consecutive term.

There have been several attempts to return Díaz's remains to Mexico since the 1920s. The most recent movement started in 2014 in Oaxaca by the Comisión Especial de los Festejos del Centenario Luctuoso de Porfirio Díaz Mori, which is headed by Francisco Jiménez. According to some, the fact that Díaz's remains have not been returned to Mexico "symbolises the failure of the post-Revolutionary state to come to terms with the legacy of the Díaz regime."[80][87]

Honors

List of notable foreign awards awarded to President Díaz:[88]

In popular culture

The main Mexican holiday is the Day of Independence, celebrated on 16 September. Americans are more familiar with Cinco de Mayo, which commemorates the date of the Battle of Puebla, in which Díaz participated, when a major victory was won against the French. Under the Porfiriato, the Mexican Consuls in the United States gave Cinco de Mayo more importance than the Day of Independence due to the President's personal involvement in the events. It is still widely celebrated in the United States, although largely due to cultural permeation.

- The film The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin (1918) has Díaz played by Pedro Sose

- The film The Mad Empress (1939) has Díaz played by Earl Gunn

- The film Juarez (1939) has Díaz played by John Garfield

- The film Porfirio Díaz (1944) is a biopic of his life

- The film My Memories of Mexico (1944) has Díaz played by Antonio R. Frausto

- The film Sobre las olas (1950) has Díaz by Antonio R. Frausto

- The film Viva Zapata! (1952) has Díaz by Fay Roope

- The film Terra em Transe (1967) uses the character metaphorically. It is interpreted by the Brazilian actor Paulo Autran and the character is portrayed as a conservative president supported by revolutionary forces.

- The Mexican soap opera La Constitución (1970) has Díaz played by Miguel Manzano

- The Mexican soap opera El Carruaje (1972) has Díaz played by Salvador Sánchez

- Porfirio Díaz is one of the main characters of the Mexican soap opera El Vuelo del Águila (1994) with Humberto Zurita as the young Díaz and Manuel Ojeda playing Díaz as President and Fabián Robles as a child

- The film Zapata - El sueño del héroe (2004) has Díaz played by Justo Martínez

- The card-game "Pax Porfiriana" (2012) has, as its theme, the competing hacendados jockeying to win out in the regime and topple Díaz.

- Post-hardcore punk band At the Drive-In has a track titled "Porfirio Díaz" on their 1996 debut album Acrobatic Tenement

- The novel All the Pretty Horses (1992) by Cormac McCarthy. Alejandra's aunt is a childhood friend of Francisco Madero. The revolution is mentioned in a monologue.

- The James Carlos Blake novels The Friends of Pancho Villa (1996), in which Díaz is a major character, and Country of the Bad Wolfes (2012), in which Díaz is a central character.

- Porfirio Díaz is referenced in chapter two of D.H. Lawrence's seminal Studies in Classical American Literature (1923), with respect to the "perfectibility of man."

- Michael Nava's novel, The City of Palaces (2014), is set against the backdrop of Porfirio's presidency and the Mexican revolution.

Gallery

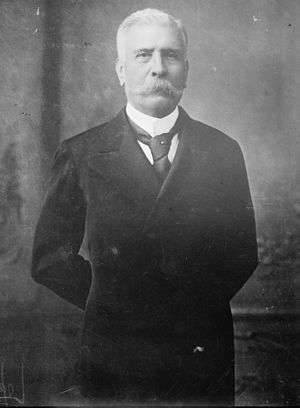

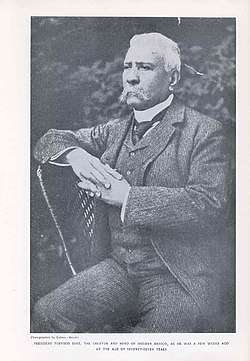

- Porfirio Díaz before 1910

Celebration of Mexico's first one hundred years of Independence in 1910, Porfirio Díaz (left) and Enrique Creel (center)

Celebration of Mexico's first one hundred years of Independence in 1910, Porfirio Díaz (left) and Enrique Creel (center)- Resignation letter of 1911

Porfirio Díaz, tomb interior

Porfirio Díaz, tomb interior Díaz family on vacation in Egypt

Díaz family on vacation in Egypt Porfirio Díaz on a horse

Porfirio Díaz on a horse

See also

References

- "Díaz". Dictionary.com.

- Stevens, D.F. "Porfirio Díaz" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 2, p. 378. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Schell,William Jr. "Politics and Government: 1876–1910" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 1111–1117.

- Vaughan, Mary Kay, "Científicos" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 2, p. 155. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Vaughan, "Cientificos", p. 155.

- Garner (2001), pp. 25, 44, n.4

- Garner (2001), p. 21

- Garner (2001), p. 25

- Britannica (1993), p. 70

- Garner (2001), p. 25

- Garner (2001), p. 26

- Garner (2001), p. 27

- Garner (2001), pp. 35, 241

- Garza, James A., "Porfirio Díaz" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 406.

- Garner (2001), p. 245

- Garner (2001), p. 246

- Garner (2001), p. 247

- Schell, "Politics and Government: 1976-1910," p. 1112

- Feller, A.H. The Mexican Claims Commissions, 1823–1934: A Study in the Law and Procedure of International Tribunals. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1935, p. 6

- Cosio Villegas, Daniel. The United States Versus Porfirio Diaz, translated by Nettie Lee Benson. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1963, p. 13.

- Garner (2001), pp. 247–248

- Garner (2001), p. 70

- Schell, "Politics and Government: 1876–1910," p. 1112.

- Krauze (1997), p. 212

- Garner (2001), p. 69

- quoted in Schell, "Politics and Government: 1876–1910", p. 1112

-

- Coerver, Don M. The Porfirian Interregnum: The Presidency of Manuel González of Mexico, 1880–1884. 1979.

- Schell, "Politics and Government: 1876–1910", pp. 1112–13.

- Schell, "Politics and Government: 1876–1910, 1113

- Buckman, Robert T. (2007). The World Today Series: Latin America 2007. Harpers Ferry, WV: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-887985-84-0.

- Crow (1992)

- Schell, "Politics and Government: 1876–1910", p. 1113

- Katz,"The Liberal Republic and the Porfiriato", p. 83

- Zayas Enríquez, Rafael (1908). Porfirio Díaz. D. Appleton. p. 31.

- Skidmore & Smith (1989)

- Baldwin, Deborah J. Protestants and the Mexican Revolution: Missionaries, Ministers, and Social Change. Urbana: University of Illinois Press 1990.

- Katz,"The Liberal Republic and the Porfiriato", p. 84

- Katz, "The Liberal Republic and the Porfiriato", p. 81

- Schell, "Politics and Government: 1876–1910"

- Katz, "The Liberal Republic and the Porfiriato", p. 84.

- Katz, "The Liberal Republic and the Porfiriato", p. 85

- Schell, "Politics and Government: 1876–1910

- Vanderwood (1970)

- Holden, R.H. Mexico and the Survey of Public Lands: The Management of Modernization, 1876 – 1911. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press 1993.

- Hart, John Mason. Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico Since the Civil War. Berkeley: University of California Press 2002.

- Katz,Friedrich "Labor Conditions on Haciendas in Porfirian Mexico: Some Trends and Tendencies," Hispanic American Historical Review, 1974, 54(1)

- 1948–, Meade, Teresa A. (19 January 2016). A history of modern Latin America : 1800 to the present (Second ed.). Chichester, West Sussex. ISBN 9781118772485. OCLC 915135785.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Eakin (2007), p. 26

- 1948–, Meade, Teresa A. (19 January 2016). A history of modern Latin America : 1800 to the present (Second ed.). Chichester, West Sussex. ISBN 9781118772485. OCLC 915135785.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Mecham (1934), p. 437

- Mecham (1934), p. 454

- Mecham (1934), pp. 454–455

- Mecham (1934), p. 456

- Mecham (1934), p. 457

- Mecham (1934), pp. 457–459

- Mecham (1934), p. 459

- Krauze (1997), pp. 227–228

- Mecham (1934), p. 460

- Schell, "Politics and Government: 1876–1910", p. 1112

- Schell, "Politics and Government: 1876–1910" p. 1114

- Schell, "Politics and Government: 1876–1910" p. 1114

- Colín, Ricardo Pacheco. "Zúñiga y Miranda, "Presidente legítimo"" (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- Harris & Sadler (2009), p. 1

- Harris & Sadler (2009), p. 2

- Zeit, Joshua (4 February 2017). "The Last Time the U.S. Invaded Mexico". Politico. Washington, D.C.

- Harris & Sadler (2009), p. 14

- Harris & Sadler (2009), p. 15

- Hampton (1910)

- van Wyk (2003), pp. 440–446

- "Mr. Taft's Peril; Reported Plot to Kill Two Presidents". Daily Mail. London. 16 October 1909. ISSN 0307-7578.

- Hammond (1935), pp. 565–566

- Harris & Sadler (2009), p. 213

- Díaz Flores Alatorre, Manuel. Recuerdo del Primer Centenario de la Independencia Nacional: Efemérides de las fiestas, recepciones, actos políticos, inauguraciones de monumentos, y de edificios, etc.. Mexico City: Rondero y Treppiedi 1910.

- "Gen. Diaz Departs and Warns Mexico". The New York Times. 31 May 1911. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- Krauze (1997), p. 213

- Krauze (1997), p. 226

- Cited in Krauze (1997), p. 227

- https://web.archive.org/web/20150420035413/http://www.archivohistorico.oaxaca.gob.mx/?q=node%2F50

- Henderson, Peter V.N. "Félix Díaz" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 404–05.

- Garner (2001), p. 12

- webmaster.rmc (23 March 2015). "Collections & History Gallery".

- Garner (2001), pp. 1–17

- Krauze (1987)

- Krauze (1997), Chapter 9, "The Triumph of the Mestizo", pp. 205–244

- Keyes (2006), p. 387

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070910071903/http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2005/08/26/026a2pol.php

- Krauze (1987), p. 150

- "Organización Editorial Mexicana".

Further reading

- Alec-Tweedie, Ethel. The Maker of Modern Mexico: Porfirio Diaz, John Lane Co., 1906.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe. Life of Porfirio Díaz, The History Company Publisher, San Francisco, 1887.

- Beals, Carleton. Porfirio Díaz, Dictator of Mexico, J.B. Lippincott & Company, Philadelphia, 1932.

- Cosío Villegas, Daniel. The United States Versus Porfirio Díaz.trans. by Nettie Lee Benson. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1963.

- Creelman, James. Diaz: Master of Mexico (New York 1911) full text online

- Garner, Paul (2001). Porfirio Díaz. Pearson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Godoy, José Francisco. Porfirio Díaz, President of Mexico, the Master Builder of a Great Commonwealth, G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1910.

- Katz, Friedrich. "The Liberal Republic and the Porfiriato, 1867-1910" in Mexico Since Independence, Leslie Bethell, ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991, pp. 49–124. ISBN 0-521-42372-4

- Krauze, Enrique (1987). Porfirio Díaz: Místico de la Autoridad. Mexico.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997. ISBN 0-06-016325-9

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1986. vol. 1

- López Obrador, Andrés Manuel (2014). Neoporfirismo: Hoy como ayer. Grijalbo. ISBN 9786073123266.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perry, Laurens Ballard. Juárez and Díaz: Machine Politics in Mexico, Northern Illinois University Press, DeKalb, IL, 1978.

- Roeder, Ralph. Hacia El México Moderno: Porfirio Díaz. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1973.

- Turner, John Kenneth. Barbarous Mexico.(1910) Austin: University of Texas Press, reprint 1969.

- Vanderwood, Paul (1970). "Genesis of the Rurales: Mexico's Early Struggle for Public Security". Hispanic American Historical Review. 50 (2): 323–344. doi:10.2307/2513029. JSTOR 2513029.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Porfiriato

- Cumberland, Charles C. Mexican Revolution: Genesis Under Madero, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1952.

- De María y Campos, Alfonso. "Porfirianos prominentes: origenes y años de juventud de ocho integrantes del group de los Científicos 1846–1876", Historia Mexicana 30 (1985), pp. 610–81.

- González Navarro, Moisés. "Las ideas raciales de los Científicos'. Historia Meixana 37 (1988) pp. 575–83.

- Hale, Charles A. Justo Sierra. Un liberal del Porfiriato. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica 1997.

- Hale, Charles A. The Transformation of Liberalism in Late Nineteenth-Century Mexico. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1989.

- Harris, Charles H. III; Sadler, Louis R. (2009). The Secret War in El Paso: Mexican Revolutionary Intrigue, 1906–1920. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4652-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hart, John Mason. Revolutionary Mexico: The Coming and Process of the Mexican Revolution, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1989.

- Priego, Natalia. Positivism, Science, and 'The Scientists' in Porfirian Mexico. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press 2016.

- Raat, William. "The Antiposivitist Movement in Pre-Revolutionary Mexico, 1892–1911", Journal of Inter-American Studies and World Affairs, 19 (1977) pp. 83–98.

- Raat, William. "Los intelectuales, el Positivismo y la cuestión indígena". Historia Mexicana 20 (1971), pp. 412–27.

- Villegas, Abelardo. Positivismo y Porfirismo. Mexico: Secreatria de Educación Pública, Col Sepsetentas 1972.

- Zea, Leopoldo, El Positivismo en México. Nacimiento apogeo y decadenica. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica 1968.

Historiography

- Benjamin, Thomas; Ocasio-Meléndez, Marcial (1984). "Organizing the Memory of Modern Mexico: Porfirian Historiography in Perspective, 1880s–1980s". Hispanic American Historical Review. 64 (2): 323–364. doi:10.1215/00182168-64.2.323. JSTOR 2514524.

- Gil, Carlos, ed. (1977). The Age of Porfirio Díaz: Selected Readings. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-0443-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Porfirio Díaz. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Porfirio Díaz |

- Historial Text Archive: Díaz, Porfirio (1830–1915)

- Works by Porfirio Díaz at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Porfirio Díaz at Internet Archive

- The New Student's Reference Work/Diaz, Porfirio

- Creelman's interview in Spanish

- Creelman's interview in English

- Newspaper clippings about Porfirio Díaz in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by José María Iglesias |

President of Mexico 28 November – 6 December 1876 |

Succeeded by Juan N. Méndez |

| Preceded by Juan N. Méndez |

President of Mexico 17 February 1877 – 1 December 1880 |

Succeeded by Manuel González Flores |

| Preceded by Manuel González Flores |

President of Mexico 1 December 1884 – 25 May 1911 |

Succeeded by Francisco León de la Barra |