Abortion in Mexico

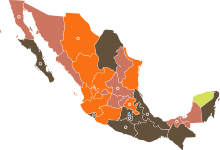

Abortion in Mexico is a controversial issue. Its legal status varies by state. The procedure is available on request to any woman up to twelve weeks into a pregnancy in Mexico City and the state of Oaxaca,[1][2] but is severely restricted in the other states.[3][4] As of April 2015, 138,792 abortions have been carried out in the capital city since its decriminalization (2007).[5] The abortion laws and their enforcement vary by region, but in conservative parts of the country, women are routinely prosecuted and convicted for having abortions: More than 679 women have been convicted for abortion in conservative-leaning states, such as Guanajuato.[4][6]

History

In 1931, fourteen years after the writing of the national Constitution, the Mexican Government addressed abortion by making it illegal, except in the cases when the abortion is caused by the negligence of the mother, continuation of the pregnancy endangers the life of the mother, or in pregnancy resulting from rape.[7][8][9]

In 1974, Mexico introduced the Ley General de Población, a law requiring the government to provide free family planning services in all public health clinics and a National Program for Family Planning to coordinate it.[10] That same year, Mexico amended its Constitution to recognize every Mexican citizen's "right to freely decide, in a responsible and informed manner, on the number and spacing of their children".[10][11] In 1991, the state of Chiapas legalized abortion.[12]

Up until the 1990s, the Mexican government considerably expanded its family planning services to rural areas and less-developed parts of the country, reducing inequalities in family planning services and contraceptive provision.[10] Contraceptive use doubled from 1976, but the annual rate of increase slowed down in 1992, and has come to a standstill in recent years.[10][13]

According to data provided by the Guttmacher Institute, in 1996, Mexico had the lowest percentage of women in Latin America who underwent an abortion procedure –1 in 40– a rate of 2.5%.[14] In 2009, Mexico's national abortion rate was at about 38 abortions per 1,000 for women between the ages of 15–44, which is at 3.8%. These rates are important to consider because of Mexico's stringent anti-abortion laws, and therefore might not be the most accurate representation of the actual data.[10][15]

Legality of abortion

On April 24, 2007, the Asamblea Legislativa de Distrito Federal or the Legislative Assembly of the Federal District (LAFD) reformed Articles 145 through 148 of the Criminal Code and Article 14 of the Health Code, all dealing with abortion. Forty-six out of the 66 members (from five distinct parties) of the Legislative Assembly of the Federal District approved the new legislation.[16] These changes expanded the previous law, which had allowed legal abortions in four limited circumstances.[17] In Mexico, abortion proceedings fall under local state legislation. A landmark Supreme Court decision in 2008 found no legal impediment to it in the federal Constitution and stated that, "to affirm that there is an absolute constitutional protection of life in gestation would lead to the violation of the fundamental rights of women".[18]

All states' penal codes permit abortions in cases of rape, and all but Guanajuato, Guerrero, and Querétaro's permit it to save the mother's life. Fourteen out of thirty-one expand these cases to include severe fetal deformities, and the state of Yucatán includes economic factors when the mother has previously borne three or more children.[19] Nevertheless, according to Jo Tuckman of The Guardian, in practice, almost no state provides access to abortions in the cases listed. They also prosecute neither the doctors who offer safe illegal abortions nor the cheaper life-threatening backstreet practitioners.[20]

There are, however, some exceptions. Since 2007, Mexico City, where approximately 7.87% of the national population lives,[21] offers abortion on request to any woman up to 12 weeks into a pregnancy,[22] which, along with Cuba and Uruguay, is one of the most liberal legislations on this matter in Latin America.[20] In contrast, recent political lobbying on behalf of the dominant Roman Catholic Church and anti-abortion organizations has resulted in the amendment of more than half of the state constitutions, which now define a fertilized human egg as a person with a right to legal protection.[23] As of 15 October 2009, none of those states removed its exceptions to abortion to reflect the changes in its constitution,[19] but according to Human Rights Watch and a local NGO, over the past eight years, the conservative-leaning state of Guanajuato "has denied every petition by a pregnant rape victim for abortion services", and about 130 of its residents have been sentenced for seeking or providing illegal abortion.[24] However, these days the government is aware of the existence of the institution called 'Las Libres de Guanajuato' which provides abortions and support for women in need, and ignores its existence.[25]

Following the decriminalization of abortions in the Distrito Federal, also known as Mexico City, the states of Baja California and San Luis Potosí enacted laws in 2008 bestowing “personhood” rights from the moment of conception.[26] In September 2011, the Supreme Court rejected two actions to overturn the laws enacted by the states of Baja California and San Luis Potosí for unconstitutionality. The Court recognized "the power of the state legislature" to enact laws on the subject. However, their decision does not criminalize or decriminalize abortion in Mexico.[7][22]

State law and court decisions

The National Supreme Court of Justice ruled on August 7, 2019 that rape victims have the right to receive abortions in public hospitals. Girls younger than 12 need parental permission.[27]

On September 25, 2019, Oaxaca became the second state, after Mexico City, to decriminalize abortion up to 12 weeks of pregnancy. The vote in the state legislature was 24 in favor and 12 against. It is estimated that 9,000 illegal abortions are performed in Oaxaca every year, 17% of them on women of 20 or younger. Abortion is the third cause of maternal mortality, and there are currently 20 women in prison for illegal abortions.[28]

In October 2019, Las Comisiones Unidas de Procuración y Administración de Justicia y de Igualdad de Género (The United Commissions for the Procuration and Administration of Justice and Gender Equality) in Puebla vote against decriminalization of abortion and legalization of same-sex marriage. The penalty for abortion is reduced from five to one year. A majority of the legislators were elected by the Together We Will Make History coalition and Marcelo García Almaguer of National Action Party called out members of National Regeneration Movement for double-talk since they call themselves "progressives" yet voted to support the criminalization of women.[29]

Influence from CEDAW

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) recognizes "the need for access to abortion services in cases where abortion is legal, and calls for a review of the laws where abortion is illegal".[16] The CEDAW Committee's recommendations to the Mexican State in 2006 specifically mention these issues.[16] CEDAW "encourages states to enact measures that ensure access to health care for women as a matter of gender equality".[16] Since Mexico signed the United Nations treaties and conventions, it is bound to above-mentioned standards.[16]

Effects of legislation

With the new legislation, the law redefines the term ‘abortion’.[16] An abortion is the legal termination of a pregnancy of 13 weeks of gestation or more.[16] During the first 12 weeks of gestation, the procedure is labeled the ‘legal termination of pregnancy’.[16] In addition, the term ‘pregnancy’ was officially defined as beginning when the embryo is implanted in the endometrium.[16] This helps to determine gestational age, and, according to the research team of Maria Sanchez Fuentes, "implicitly legitimizes any post-coital contraceptive method, including emergency contraception ... and assisted reproduction (including infertility treatments such as IVF) and stem-cell research".[16] Women charged with having an illegal abortion have their sentences reduced, and the penalty for forcing a woman to have an abortion against her own will, which includes her partner or a physician, is increased.[16] If physical violence is involved, the penalty is even higher.[16] Furthermore, the law explicitly states that sexual and reproductive health are a priority in health services, with the goal of preventing unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).[16]

According to an unofficial report by the organization Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida (GIRE), between 2009 and 2011, 679 women have charged with the crime of abortion in the interior of the country.[30][31] In the report, GIRE states that having legislation for each entity makes "access to abortion a matter of social injustice and gender discrimination."[30][31] According to the Omisión e Indiferencia: Derechos reproductivos en México (known as Omission and Indifference: Reproductive Rights in Mexico) presented by GIRE, only women with economic resources and information can travel to Mexico City to have an abortion "without the risk of being persecuted for committing a crime or do it in precarious conditions."[30][31][32] Although there are no official figures on clandestine abortions in the country, GIRE estimated that in 2009 159,000 women rushed to a hospital for complications of unsafe and illegal abortions.[30][31][32]

In addition, restrictive abortion policies not only limit women's individual agency and autonomy, but force poor women to choose between an unsafe illegal medical procedure, and bearing unwanted children.[16] Thus, such policies create structural social and economic inequality.[16]

Impact on health and the economy

Research done by Maria Sanchez Fuentes et al. concludes that the health and economic costs of unsafe abortion are very high, in common with other preventable illnesses.[16] Moreover, those costs are higher for poor women, because only women with economic means and sufficient information can access abortion under safe medical conditions in Mexico, or travel to foreign countries where abortion is legal throughout.[16] After the amendments to the abortion law in 2007, abortion services are now free of charge in public hospitals for Mexico City residents, which account for approximately one quarter of the country's population, and available for a moderate fee for women from other states or countries.[16]

Before the passage of the amendments to the abortion law, many Mexican women would buy herbs from the market and try dangerous home versions of abortion in order to end their unwanted pregnancies [33] Women also resorted to buying prescription drugs, obtained from pharmacists without a doctor's signature, that would induce an abortion.[33] Moreover, some women even ingested huge doses of drugs for arthritis and gastritis, available over the counter, which can cause miscarriages.[33] All of these methods are significantly dangerous, and most are illegal.

The fifth leading cause of maternal mortality in Mexico is illegal, unsafe abortion.[16][34] A huge proportion of poor and young women are forced to risk their health and lives in the conditions under which many clandestine abortions are practiced.[16] This highlights the costs of unsafe abortion to the public-health system.[16] In addition, women who undergo unsafe abortions and suffer complications or death represent the fourth highest cause of hospital admissions in Mexico's public hospitals.[16] The Ministry of Health statistics show that in Mexico City, maternal mortality has been reduced significantly since the passage of the new law.[33]

During 2008, the public health sector, under Mexico City's Ministry of Health, carried out 13,057 legal abortions, compared to 66 abortions between 2002 and 2007, when the legal indications were restricted to the four circumstances of rape, danger to the woman's life and health and congenital malformations.[35] At the end of April 2007, the city's Ministry of Health started providing first trimester abortions free of charge to the estimated 43 percent of women residing in Mexico City with no public health insurance.[35]

Demographics and public opinion

A 2008 study funded by the National Population Council (CONAPO), El Colegio de México and the Guttmacher Institute estimated 880,000 abortions carried out annually, with an average of 33 abortions a year for every 1,000 women between the ages of 15 and 44.[36] However, such studies are speculative —as abortion is highly restricted and reliable data is not readily available— with some estimates ranging as low as 297,000 abortions per year.[37]

By January 19, 2011, 52,484 abortions have been carried out in Mexico City since its decriminalization in 2007,[3] where some 85 percent of the gynecologists in the city's public hospitals have declared themselves conscientious objectors.[38] Among the petitioners, 78% were local residents, 21% were living out-of-state and 1% were foreigners from countries such as Germany, Argentina and Canada.[3] As for their age, 0.6% were between 11 and 14, 47.6% were between 18 and 24, 22% between 25 and 29, 13% between 30 and 34 and 2.7% between 40 and 44 years old. More than half were single.[3]

As of April 2012, roughly 78,544 women had undergone free legal terminations of pregnancy (LTP) without major complications – an average of 15,709 per year since the law passed in 2007.[30][39] According to the United Nations, more than 500,000 Mexican women seek illegal abortions every year, with more than 2,000 dying from botched or unsafe procedures.[17][40]

Political community

In the presidential election of 2006, a conservative candidate from the PAN won the election by an "infinitesimal percentage, and the progressive PRD candidate claimed fraud."[16] An article by Sanchez Fuentes et al., suggested that this caused polarization between the two parties and within Mexican society in general.[16] Since the PRD lost the presidential election, but maintained control of the local legislature and Mayor's Office in Mexico City, they demonstrated the differences between the left- and right-wing parties in the reproductive-rights context by supporting the change in the law.[16]

In 2007, the legal proposal to decriminalize abortion, led by the PRI, was introduced in the Mexico City Legislative Assembly (LAFD).[33] In this Mexico City abortion reform, "the policy community (including the center-left political parties; the Mexico City government, represented by the Mayor's Office; the local Ministry of Health; and the local Human Rights Ombudsman), along with academics, opinion leaders, and leading scientists, was very much united, and vocal in support of decriminalization".[16] Mexico City's then-mayor Marcelo Ebrard, from the PRD, declared, "This is a women's cause, but it is also the city's cause."[16] Manifestations of support for the bill came in the form of public announcements by public figures, printed in national newspapers, which are a key means of influencing public opinion and debate in Mexico, as well as via press declarations, and interviews, as suggested by.[16] A public announcement published on April 17, 2007, by the Academy of Bioethics, which outlined why the decriminalization of up to 12 weeks was not contradictory to scientific evidence, affirmed that, "an embryo at this stage has not developed a cerebral cortex or nerve endings, does not feel pain, and is not a human being or person".[16] Sanchez Fuentes et al. concluded that this bioethics perspective influenced the discourse surrounding the debate.[16]

Anti-abortion movement by the Catholic Church

Knowing the potential involvement of the Catholic church on this reform, LAFD pitched the debate as a necessary protection for women-particularly poor women.[17] This justification was meant to resonate especially with the largely Catholic population, religious interest groups, and the Catholic healthcare professionals.[17] While public opinion in Mexico City is largely in favor of legal abortion, the negotiation with religious as well as conscientiously objecting doctors and nurses was proven difficult.[17][41] Their religious faith had a major impact on the negotiation, because of Catholic's view on abortion as a sin.

The anti-abortion movement in Mexico has been led by the Catholic Church.[17] The Church remains influential in Mexico, and in any discussion of abortion, the government must discuss the reactions and policies of the Church.[17] It is also the Church's influence that has guided the debate towards a health rationale rather than a choice rationale – staying away from a pro-choice stance.[17] After the law was passed in April 2007, the Catholic Church collected 70,000 signatures supporting an abortion referendum.[33]

Under Articles 6 and 24, the Mexican constitution protects citizens with freedom of religion in Mexico.[17] During the first few weeks after the law passed in 2007, many doctors and nurses did not partake in abortions due to their faith.[17][42][43] The LAFD dealt with the Church's influence on public hospitals and their employees by reinforcing the reforms made in the Robles law (the law permitting abortion to be legal in Federal District (Mexico) and requiring, in Article 14 Bis 6 of the Health Law, that once again hospitals must have non-objecting doctors on call for abortions).[17] The Robles Law uses language that makes it clear that the right to object on religious grounds is not absolute and that the woman's right to receive the abortion trumps the doctor's right to object where no non-objecting doctor can be located.[17] Furthermore, Article 14 Bis 3 established the Clinical Commission for Evaluation to ensure that doctors were performing abortions and that every time a woman requests information about an abortion, it is recorded by an independent, centralized body of the government.[17] Former Secretary of Health, Manuel Mondragon, under the Mayor of Mexico City, Marcelo Ebrard, worked to make sure that abortions were readily available to women who sought them under the legal circumstances.[17] Essentially, the law incorporates a conscientious objection exemption for health care providers, and similarly requires that hospitals then provide a woman with an alternate provider, who will perform the abortion.[17][42] Furthermore, the separation of church and state is enshrined in the Mexican Reform Laws of 1859.[16] Therefore, the attempt by the Church to influence politics was illegal, and their threat of excommunication was invalid.[16] The major separation of the church and state did not permit for religious reasoning to be the major influence on policies, but the Catholic church threatened to prohibit the individuals supporting the policy from attending any religious sanctions and ceremonies.

According to Sanchez Fuentes et al., more than 80 percent of the women who have sought services are Catholic, and formally educated, claiming to help destigmatize abortion, influencing public opinion.[16]

Recent surveys

- In a May 2005 Consulta Mitofsky survey, when asked, "Would you agree or disagree with the legalization of abortion in Mexico?", 51% of polltakers said that they would disagree, 47.9% said that they would agree, and 1.1% said that they were unsure.[44]

- A November 2005 IMO survey found that 73.4% of Mexicans think abortion should not be legalized, while 11.2% think it should.[45]

- A January 2007 Consulta Mitofsky poll examined attitudes toward birth control methods in Mexico, asking, "Currently, there are many methods meant to prevent or terminate a pregnancy. In general, do you agree with the following methods?" 32.1% of respondents stated that they agreed with abortion.[46]

- A March 2007 Parametría survey compared the opinions of people living in Mexico City with those living throughout the rest of the country, asking, "Do you agree or disagree with allowing women to have an abortion without being penalized, if the procedure takes place within the first 14 weeks of a pregnancy?" In Mexico City, 44% said they "agree", 38% that they "disagree", 14% that they "neither" agree nor disagree, and 3% that they are "not sure". Throughout the rest of Mexico, 58% of those surveyed said that they "disagree", 23% that they "agree", 15% that they "neither" agree nor disagree, and 4% that they are "not sure".[47]

See also

- Mexico City Policy

- Law of Mexico

- Verónica Cruz Sánchez

References

- "Mexico's Oaxaca state legalizes abortion in historic move". jpost.com. The Jerusalem Post. 2019-09-26. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- Agren, David (2019-09-26). "'We have made history': Mexico's Oaxaca state decriminalises abortion". theguardian.com. The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- Gómez, Natalia (6 February 2011). "Realizan abortos legales sin regulación". El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- Gaestel, Allyn; Shelley, Allison (1 October 2014). "Mexican women pay high price for country's rigid abortion laws". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- "Se han interrumpido legalmente 138 mil embarazos en ocho años". Excélsior (in Spanish). Notimex. 23 April 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- Malkin, Elisabeth (22 September 2010). "Many States in Mexico Crack Down on Abortion". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- Jelen, Ted G.; Jonathan Doc Bradley (2012). "Abortion Opinion in Emerging Democracies: Latin America and Central Europe" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Hassmann, Melissa (2005). Abortion Politics in North America. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishing, Inc.

- department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, Policy Data Bank. "UN Report-Mexico". Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Juarez, F (2013). Unintended Pregnancy and Induced Abortion in Mexico: Causes and Consequences (PDF). New York: Guttmacher Institute.

- Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. "Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, Capítulo I de los Derechos Humanos y sus Garantías, Artículo 4" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- Cad. “Mexico: State Loosens Abortion Law.” Off Our Backs, vol. 21, no. 3, 1991, pp. 11–11. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20833453 accessed 21 March 2019

- Fuentes, M Urbina (2005). Política de población y los programas de planificación familiar, en: Valdés L ed., La ley de población a treinta años de distancia: reflexiones, análisis y propuestas (in Spanish). Mexico City: UNAM. pp. 339–353.

- "An Overview of Clandestine Abortion in Latin America". Guttmacher Institute. December 1996. Archived from the original on 2014-03-17. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "Fact Sheet: Unintended Pregnancy and Induced Abortion In Mexico". Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Sanchez Fuentes, Maria Luisa; Jennifer Paine; Brook Elliott-Buettner (July 2008). "The Decriminalisation of Abortion in Mexico City: How Did Abortion Rights Become a Political Priority?". Gender and Development. 16 (2): 345–360. doi:10.1080/13552070802120533. JSTOR 20461278. S2CID 146457306.

- Johnson, Thea B. (2013). "GUARANTEED ACCESS TO SAFE AND LEGAL ABORTIONS: THE TRUE REVOLUTION OF MEXICO CITY'S LEGAL REFORMS REGARDING ABORTION" (PDF). Columbia Human Rights Law Review. 2. 44 (437). Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- Miller Llana, Sara (2008-08-28). "Mexico's Supreme Court upholds abortion law". Christian Science Monitor. Mexico City. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- "State Legislation". Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida, A.C. 2012. Archived from the original on 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2012-07-24.

- Tuckman, Jo (2008-08-29). "Judges uphold abortion rights in Mexico City". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- "Population of Mexico City as a percentage of the national population of Mexico". Wolfram Alpha. 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- Ellingwood, Ken (2008-08-29). "Mexican Supreme Court upholds legalized abortion law". Los Angeles Times. Mexico City. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- "Temen se extienda prohibición al aborto en el país". El Financiero en línea (in Spanish). Mexico City. 2009-10-13. Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- "Mexico: Stop Blocking Abortions for Rape Victims". New York: Human Rights Watch. 2009-03-05. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- Lysakowska, Anna (2014). "The Politics of Abortion in Mexico: A study based on the examples of the states of Distrito Federal and Guanajuato". ISBN 978-3659527661.

- "La legalidad del aborto en México a discusión en la Suprema Corte". CNN. 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "México: La Corte Suprema de Justicia avala aborto por violación" [Mexico: Supreme Court approves abortion in cases of rape]. CNN Espanol (in Spanish). August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- "Congreso de Oaxaca aprueba despenalizar el aborto" [Congress of Oaxaca decriminalizes abortion], Milenio (in Spanish), Sep 25, 2019, retrieved Oct 5, 2019

- Gabriela Hernandez (Oct 5, 2019), "Legisladores poblanos cierran paso a la despenalización del aborto y al matrimonio igualitario" [Puebla legislators close path to decriminalization of abortion and legalization of equal marriage], Proceso (in Spanish)

- Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida. "Cifras del aborto en México". Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Montalvo, Tania (24 April 2013). "Una de cada 3 mujeres que interrumpe su embarazo en el DF es ama de casa". CNN: Mexico. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- Grupo de Informacion en Reproduccion Elegida. "Aborto: Capitulo Uno" (PDF). GIRE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Ford, Allison (2010). "MEXICO CITY LEGALIZES ABORTION". Law and Business Review of the Americas. 16 (1): 119–127. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Wilson, Kate S.; Sandra G. Garcia; Cudia Diaz Olvarrieta; Aremic Villalobos-Hernandez; Jorge Valencia Rodriguez; Patricio Sanhueza Smith; Courtney Burks (September 2011). "Public Opinion on Abortion in Mexico City after the Landmark Reform". Studies in Family Planning. 42 (3): 175–182. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2011.00279.x. JSTOR 41310727. PMID 21972670.

- Schiavon, Rafael; Maria E. Collado; Erika Troncoso; Jose E. Soto Sanchez; Gabriela Otero Zorrilla; Tia Palermo (November 2010). "Characteristics of private abortion services in Mexico City after legalization". Reproductive Health Matters. 18 (36): 127–135. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36530-X. JSTOR 25767368. PMID 21111357. S2CID 15771389.

- Cevallos, Diego (2009-05-22). "Avalanche of Anti-Abortion Laws". Inter Press Service. Archived from the original on 2009-07-26. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- Henshaw, Stanley (1999-01-01). "The Incidence of abortion Worldwide". International Family Planning Perspectives. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- Malkin, Elisabeth; Cattan, Nacha (24 August 2008). "Mexico City Struggles With Law on Abortion". The New York Times. p. A5. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- Amuchástegui, Ana (2013). "Body and embodiment in the experience of abortion for Mexican women: the sexual body, the fertile body, and the body of abortion". Gender, Sexuality & Feminism. 1 (1). doi:10.3998/gsf.12220332.0001.101.

- Malcolm Moore; Jerry McDermott (26 April 2007). "Catholics to appeal Mexico City's abortion law". Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- Wilson, Kate S.; García SG; Díaz Olavarrieta C; Villalobos-Hernández A; Rodríguez JV; Smith PS; Burks C. (September 2011). "Public opinion on abortion in Mexico City after the landmark reform". Studies in Family Planning. 42 (3): 175–182. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2011.00279.x. PMID 21972670.

- ELISABETH MALKIN; NACHA CATTAN (24 August 2008). "Mexico City Struggles With Law on Abortion". New York Times. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Tobar, Hector (3 November 2007). "In Mexico, abortion is out from shadows". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Mexico Deeply Divided on Social Issues Archived June 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine." (July 5, 2005). Angus Reid Global Monitor. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- "Mexicans Support Status Quo on Social Issues Archived December 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine." (December 1, 2005). Angus Reid Global Monitor. Retrieved January 10, 2006.

- "Mexicans Support Birth Control, Not Abortion Archived March 31, 2007, at the Wayback Machine." (March 28, 2007). Angus Reid Global Monitor. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- "Urban-Rural Abortion Divide Evident in Mexico Archived June 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine." (April 15, 2007). Angus Reid Global Monitor. Retrieved June 20, 2007.