Carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. It is toxic to animals that use hemoglobin as an oxygen carrier (both invertebrate and vertebrate) when encountered in concentrations above about 35 ppm, although it is also produced in normal animal metabolism in low quantities, and is thought to have some normal biological functions. In the atmosphere, it is spatially variable and short-lived, having a role in the formation of ground-level ozone.

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Carbon monoxide | |||

| Other names

Carbon monooxide Carbonous oxide Carbon(II) oxide Carbonyl Flue gas Monoxide | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| 3587264 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.010.118 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 421 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Carbon+monoxide | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1016 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| CO | |||

| Molar mass | 28.010 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | colorless gas | ||

| Odor | odorless | ||

| Density | 789 kg/m3, liquid 1.250 kg/m3 at 0 °C, 1 atm 1.145 kg/m3 at 25 °C, 1 atm | ||

| Melting point | −205.02 °C (−337.04 °F; 68.13 K) | ||

| Boiling point | −191.5 °C (−312.7 °F; 81.6 K) | ||

| 27.6 mg/L (25 °C) | |||

| Solubility | soluble in chloroform, acetic acid, ethyl acetate, ethanol, ammonium hydroxide, benzene | ||

Henry's law constant (kH) |

1.04 atm·m3/mol | ||

| −9.8·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.0003364 | ||

| 0.122 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C) |

29.1 J/(K·mol) | ||

Std molar entropy (S |

197.7 J/(mol·K) | ||

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−110.5 kJ/mol | ||

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−283.4 kJ/mol | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| V04CX08 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | See: data page ICSC 0023 | ||

| GHS pictograms |    | ||

| GHS Signal word | Danger | ||

GHS hazard statements |

H220, H331, H360, H372 | ||

| P201, P202, P210, P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P281, P304+340, P308+313, P311, P314, P321, P377, P381, P403, P403+233, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | −191 °C (−311.8 °F; 82.1 K) | ||

| 609 °C (1,128 °F; 882 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 12.5–74.2% | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LC50 (median concentration) |

8636 ppm (rat, 15 min) 5207 ppm (rat, 30 min) 1784 ppm (rat, 4 h) 2414 ppm (mouse, 4 h) 5647 ppm (guinea pig, 4 h)[2] | ||

LCLo (lowest published) |

4000 ppm (human, 30 min) 5000 ppm (human, 5 min)[2] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits):[3] | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 50 ppm (55 mg/m3) | ||

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 35 ppm (40 mg/m3) C 200 ppm (229 mg/m3) | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

1200 ppm | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related carbon oxides |

Carbon dioxide Carbon suboxide Oxocarbons | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |||

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas | ||

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

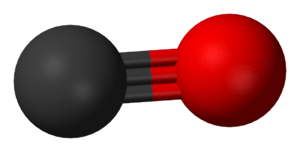

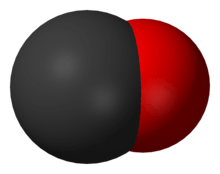

Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom, connected by a triple bond that consists of a net two pi bonds and one sigma bond. It is the simplest oxocarbon and is isoelectronic with other triply-bonded diatomic species possessing 10 valence electrons, including the cyanide anion, the nitrosonium cation, boron monofluoride and molecular nitrogen. In coordination complexes the carbon monoxide ligand is called carbonyl.

History

Aristotle (384–322 BC) first recorded that burning coals produced toxic fumes. An ancient method of execution was to shut the criminal in a bathing room with smoldering coals. What was not known was the mechanism of death. Greek physician Galen (129–199 AD) speculated that there was a change in the composition of the air that caused harm when inhaled.[5] In 1776, the French chemist de Lassone produced CO by heating zinc oxide with coke, but mistakenly concluded that the gaseous product was hydrogen, as it burned with a blue flame. The gas was identified as a compound containing carbon and oxygen by the Scottish chemist William Cruickshank in 1800.[6][7] Its toxic properties on dogs were thoroughly investigated by Claude Bernard around 1846.[8]

During World War II, a gas mixture including carbon monoxide was used to keep motor vehicles running in parts of the world where gasoline and diesel fuel were scarce. External (with a few exceptions) charcoal or wood gas generators were fitted, and the mixture of atmospheric nitrogen, hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and small amounts of other gases produced by gasification was piped to a gas mixer. The gas mixture produced by this process is known as wood gas. Carbon monoxide was also used on a large scale during the Holocaust at some Nazi German extermination camps, the most notable by gas vans in Chełmno, and in the Action T4 "euthanasia" program.[9]

Sources

Carbon monoxide is produced from the partial oxidation of carbon-containing compounds; it forms when there is not enough oxygen to produce carbon dioxide (CO2), such as when operating a stove or an internal combustion engine in an enclosed space. In the presence of oxygen, including atmospheric concentrations, carbon monoxide burns with a blue flame, producing carbon dioxide.[10] Coal gas, which was widely used before the 1960s for domestic lighting, cooking, and heating, had carbon monoxide as a significant fuel constituent. Some processes in modern technology, such as iron smelting, still produce carbon monoxide as a byproduct.[11] A large quantity of CO byproduct is formed during the oxidative processes for the production of chemicals. For this reason, the process off-gases have to be purified. On the other hand, considerable research efforts are made in order to optimize the process conditions,[12] develop catalyst with improved selectivity [13] and to understand the reaction pathways leading to the target product and side products.[14][15]

Worldwide, the largest source of carbon monoxide is natural in origin, due to photochemical reactions in the troposphere that generate about 5*10^12 kilograms per year.[16] Other natural sources of CO include volcanoes, forest fires, other forms of combustion, and carbon monoxide-releasing molecules.

In biology, carbon monoxide is naturally produced by the action of heme oxygenase 1 and 2 on the heme from hemoglobin breakdown. This process produces a certain amount of carboxyhemoglobin in normal persons, even if they do not breathe any carbon monoxide. Following the first report that carbon monoxide is a normal neurotransmitter in 1993,[17][18] as well as one of three gases that naturally modulate inflammatory responses in the body (the other two being nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide), carbon monoxide has received a great deal of clinical attention as a biological regulator. In many tissues, all three gases are known to act as anti-inflammatories, vasodilators, and promoters of neovascular growth.[19] Clinical trials of small amounts of carbon monoxide as a drug are ongoing.[20] Too much carbon monoxide causes carbon monoxide poisoning.

Some deep-diving marine mammal species are known to contain concentrations of carbon monoxide in their blood that resembles levels seen in chronic cigarette smokers [21]. It is believed these elevated levels of CO will increase the animals' hemoglobin-oxygen affinity, which can help the animals more efficiently deliver oxygen during the events of severe hypoxemia they routinely encounter during long duration dives. Further, these levels of CO could help the animals with the prevention of injuries associated ischemia/reperfusion events associated with the physiological dive response [22].

Molecular properties

Carbon monoxide has a molar mass of 28.0, which, according to the ideal gas law, makes it slightly less dense than air, whose average molar mass is 28.8.

The bond length between the carbon atom and the oxygen atom is 112.8 pm.[23][24] This bond length is consistent with a triple bond, as in molecular nitrogen (N2), which has a similar bond length (109.76 pm) and nearly the same molecular mass. Carbon–oxygen double bonds are significantly longer, 120.8 pm in formaldehyde, for example.[25] The boiling point (82 K) and melting point (68 K) are very similar to those of N2 (77 K and 63 K, respectively). The bond-dissociation energy of 1072 kJ/mol is stronger than that of N2 (942 kJ/mol) and represents the strongest chemical bond known.[26]

The ground electronic state of carbon monoxide is a singlet state[27] since there are no unpaired electrons.

Bonding and dipole moment

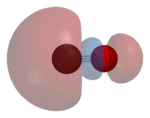

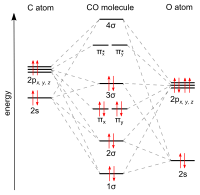

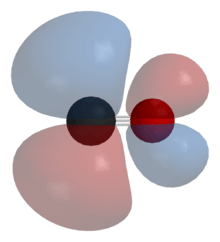

Carbon and oxygen together have a total of 10 electrons in the valence shell. Following the octet rule for both carbon and oxygen, the two atoms form a triple bond, with six shared electrons in three bonding molecular orbitals, rather than the usual double bond found in organic carbonyl compounds. Since four of the shared electrons come from the oxygen atom and only two from carbon, one bonding orbital is occupied by two electrons from oxygen, forming a dative or dipolar bond. This causes a C←O polarization of the molecule, with a small negative charge on carbon and a small positive charge on oxygen. The other two bonding orbitals are each occupied by one electron from carbon and one from oxygen, forming (polar) covalent bonds with a reverse C→O polarization, since oxygen is more electronegative than carbon. In the free carbon monoxide molecule, a net negative charge δ– remains at the carbon end and the molecule has a small dipole moment of 0.122 D.[28]

The molecule is therefore asymmetric: oxygen has more electron density than carbon, and is also slightly positively charged compared to carbon being negative. By contrast, the isoelectronic dinitrogen molecule has no dipole moment.

Carbon monoxide has a computed fractional bond order of 2.6, indicating that the "third" bond is important but constitutes somewhat less than a full bond.[29] Thus, in valence bond terms, –C≡O+ is the most important structure, while :C=O is non-octet, but has a neutral formal charge on each atom and represents the second most important resonance contributor. Because of the lone pair and divalence of carbon in this resonance structure, carbon monoxide is often considered to be an extraordinarily stabilized carbene.[30] Isocyanides are compounds in which the O is replaced by an NR (R = alkyl or aryl) group and have a similar bonding scheme.

If carbon monoxide acts as a ligand, the polarity of the dipole may reverse with a net negative charge on the oxygen end, depending on the structure of the coordination complex.[31] See also the section "Coordination chemistry" below.

Bond polarity and oxidation state

Theoretical and experimental studies show that, despite the greater electronegativity of oxygen, the dipole moment points from the more-negative carbon end to the more-positive oxygen end.[32][33] The three bonds are in fact polar covalent bonds that are strongly polarized. The calculated polarization toward the oxygen atom is 71% for the σ-bond and 77% for both π-bonds.[34]

The oxidation state of carbon in carbon monoxide is +2 in each of these structures. It is calculated by counting all the bonding electrons as belonging to the more electronegative oxygen. Only the two non-bonding electrons on carbon are assigned to carbon. In this count, carbon then has only two valence electrons in the molecule compared to four in the free atom.

Biological and physiological properties

Toxicity

Carbon monoxide poisoning is the most common type of fatal air poisoning in many countries.[35] Carbon monoxide is colorless, odorless, and tasteless, but highly toxic. It combines with hemoglobin to produce carboxyhemoglobin, by binding to the site in hemoglobin that normally carries oxygen, leaving it ineffective for delivering oxygen to bodily tissues. Concentrations as low as 667 ppm may cause up to 50% of the body's hemoglobin to convert to carboxyhemoglobin.[36] A level of 50% carboxyhemoglobin may result in seizure, coma, and fatality. In the United States, the OSHA limits long-term workplace exposure levels above 50 ppm.[37]

The most common symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning may resemble other types of poisonings and infections, including symptoms such as headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, fatigue, and a feeling of weakness. Affected families often believe they are victims of food poisoning. Infants may be irritable and feed poorly. Neurological signs include confusion, disorientation, visual disturbance, syncope (fainting), and seizures.[38]

Some descriptions of carbon monoxide poisoning include retinal hemorrhages, and an abnormal cherry-red blood hue.[39] In most clinical diagnoses these signs are seldom noticed.[38] One difficulty with the usefulness of this cherry-red effect is that it corrects, or masks, what would otherwise be an unhealthy appearance, since the chief effect of removing deoxygenated hemoglobin is to make an asphyxiated person appear more normal, or a dead person appear more lifelike, similar to the effect of red colorants in embalming fluid. The "false" or unphysiologic red-coloring effect in anoxic CO-poisoned tissue is related to the meat-coloring commercial use of carbon monoxide, discussed below.

Carbon monoxide also binds to other molecules such as myoglobin and mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase. Exposures to carbon monoxide may cause significant damage to the heart and central nervous system, especially to the globus pallidus,[40] often with long-term chronic pathological conditions. Carbon monoxide may have severe adverse effects on the fetus of a pregnant woman.[41]

Normal human physiology

Carbon monoxide is produced naturally by the human body as a signaling molecule. Thus, carbon monoxide may have a physiological role in the body, such as a neurotransmitter or a blood vessel relaxant.[42] Because of carbon monoxide's role in the body, abnormalities in its metabolism have been linked to a variety of diseases, including neurodegenerations, hypertension, heart failure, and pathological inflammation.[42] Relative to inflammation, carbon monoxide has been shown to inhibit the movement of leukocytes to inflamed tissues, stimulate leukocyte phagocytosis of bacteria, and reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by leukocytes. In animal model studies, furthermore, carbon monoxide reduced the severity of experimentally induced bacterial sepsis, pancreatitis, hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury, colitis, osteoarthritis, lung injury, lung transplantation rejection, and neuropathic pain while promoting skin wound healing. These actions are similar to those of Specialized pro-resolving mediators which act to dampen, reverse, and repair the tissue damage due to diverse inflammation responses. Indeed, carbon monoxide can act additively with one of these mediators (Resolvin D1) to limit inflammatory responses. The studies implicate carbon monoxide as a physiological contributor to limiting inflammation and suggest that its delivery by inhalation or carbon monoxide-forming drugs may be therapeutically useful for controlling pathological inflammatory responses.[43][44][45][46]

CO functions as an endogenous signaling molecule, modulates functions of the cardiovascular system, inhibits blood platelet aggregation and adhesion, suppresses, reverses, and repairs the damage caused by inflammatory responses. It may play a role as potential therapeutic agent.[43][47]

Microbiology

Carbon monoxide is a nutrient for methanogenic archaea, which reduce it to methane using hydrogen.[48] This is the theme for the emerging field of bioorganometallic chemistry. Extremophile micro-organisms can, thus, utilize carbon monoxide in such locations as the thermal vents of volcanoes.[49]

Some microbes can convert carbon monoxide to carbon dioxide to yield energy.[50]

In bacteria, carbon monoxide is produced via the reduction of carbon dioxide by the enzyme carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, an Fe-Ni-S-containing protein.[51]

CooA is a carbon monoxide sensor protein.[52] The scope of its biological role is still unknown; it may be part of a signaling pathway in bacteria and archaea. Its occurrence in mammals is not established.

Occurrence

Carbon monoxide occurs in various natural and artificial environments. Typical concentrations in parts per million are as follows:

| ppmv: parts per million by volume (note: volume fraction is equal to mole fraction for ideal gas only, see volume (thermodynamics)) | |

| Concentration | Source |

|---|---|

| 0.1 ppmv | Natural atmosphere level (MOPITT)[55] |

| 0.5–5 ppmv | Average level in homes[56] |

| 5–15 ppmv | Near properly-adjusted gas stoves in homes, modern vehicle exhaust emissions[57] |

| 17 ppmv | Atmosphere of Venus |

| 100–200 ppmv | Exhaust from automobiles in the Mexico City central area in 1975[58] |

| 700 ppmv | Atmosphere of Mars |

| <1000 ppmv | Car exhaust fumes after passing through catalytic converter[59] |

| 5,000 ppmv | Exhaust from a home wood fire[60] |

| 30,000–100,000ppmv | Undiluted warm car exhaust without a catalytic converter[59] |

Atmospheric presence

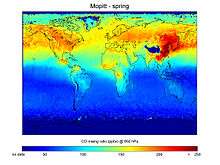

Carbon monoxide (CO) is present in small amounts (about 80 ppb) in the Earth's atmosphere. About half of the carbon monoxide in Earth's atmosphere is from the burning of fossil fuels and biomass (such as forest and bushfires).[61] Most of the rest comes from chemical reactions with organic compounds emitted by human activities and plants. Small amounts are also emitted from the ocean, and from geological activity because carbon monoxide occurs dissolved in molten volcanic rock at high pressures in the Earth's mantle.[62] Because natural sources of carbon monoxide are so variable from year to year, it is difficult to accurately measure natural emissions of the gas.

Carbon monoxide has an indirect effect on radiative forcing by elevating concentrations of direct greenhouse gases, including methane and tropospheric ozone. CO can react chemically with other atmospheric constituents (primarily the hydroxyl radical, OH.) that would otherwise destroy methane.[63] Through natural processes in the atmosphere, it is oxidized to carbon dioxide and ozone. Carbon monoxide is short-lived in the atmosphere (with an average lifetime of about one to two months), and spatially variable in concentration.[64]

In the atmosphere of Venus carbon monoxide occurs as a result of the photodissociation of carbon dioxide by electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths shorter than 169 nm.

Due to its long lifetime in the mid-troposphere, carbon monoxide is also used as tracer for pollutant plumes.[65]

Urban pollution

Carbon monoxide is a temporary atmospheric pollutant in some urban areas, chiefly from the exhaust of internal combustion engines (including vehicles, portable and back-up generators, lawn mowers, power washers, etc.), but also from incomplete combustion of various other fuels (including wood, coal, charcoal, oil, paraffin, propane, natural gas, and trash).

Large CO pollution events can be observed from space over cities.[66]

Role in ground-level ozone formation

Carbon monoxide is, along with aldehydes, part of the series of cycles of chemical reactions that form photochemical smog. It reacts with hydroxyl radical (•OH) to produce a radical intermediate •HOCO, which transfers rapidly its radical hydrogen to O2 to form peroxy radical (HO2•) and carbon dioxide (CO2).[67] Peroxy radical subsequently reacts with nitrogen oxide (NO) to form nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and hydroxyl radical. NO2 gives O(3P) via photolysis, thereby forming O3 following reaction with O2. Since hydroxyl radical is formed during the formation of NO2, the balance of the sequence of chemical reactions starting with carbon monoxide and leading to the formation of ozone is:

- CO + 2O2 + hν → CO2 + O3

(where hν refers to the photon of light absorbed by the NO2 molecule in the sequence)

Although the creation of NO2 is the critical step leading to low level ozone formation, it also increases this ozone in another, somewhat mutually exclusive way, by reducing the quantity of NO that is available to react with ozone.[68]

Indoor pollution

In closed environments, the concentration of carbon monoxide can easily rise to lethal levels. On average, 170 people in the United States die every year from carbon monoxide produced by non-automotive consumer products.[69] According to the Florida Department of Health, "every year more than 500 Americans die from accidental exposure to carbon monoxide and thousands more across the U.S. require emergency medical care for non-fatal carbon monoxide poisoning"[70] These products include malfunctioning fuel-burning appliances such as furnaces, ranges, water heaters, and gas and kerosene room heaters; engine-powered equipment such as portable generators; fireplaces; and charcoal that is burned in homes and other enclosed areas. The American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) reported 15,769 cases of carbon monoxide poisoning resulting in 39 deaths in 2007.[71] In 2005, the CPSC reported 94 generator-related carbon monoxide poisoning deaths.[69] Forty-seven of these deaths were known to have occurred during power outages due to severe weather, including Hurricane Katrina.[69] Still others die from carbon monoxide produced by non-consumer products, such as cars left running in attached garages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that several thousand people go to hospital emergency rooms every year to be treated for carbon monoxide poisoning.[72]

Biological sources

Carbon monoxide is produced in heme catabolism and thus is present in blood. Normal circulating levels in the blood are 0% to 3% saturation,[73] i.e. the ratio of the amount of carboxyhaemoglobin present to the total circulating haemoglobin,[74] and are higher in smokers. Some deep-diving marine mammal species are known to maintain carboxyhemoglobin levels between 5-10% [21]. Carbon monoxide levels cannot be assessed through a physical exam. Laboratory testing requires a blood sample (arterial or venous) and laboratory analysis on a CO-Oximeter. Additionally, a noninvasive carboxyhemoglobin (SpCO) test method from Pulse CO-Oximetry exists and has been validated compared to invasive methods.[75]

A carbon monoxide sensor protein, CooA, has been characterized in bacteria.

Astronomy

Beyond Earth, carbon monoxide is the second-most common molecule in the interstellar medium, after molecular hydrogen. Because of its asymmetry, this polar molecule produces far brighter spectral lines than the hydrogen molecule, making CO much easier to detect. Interstellar CO was first detected with radio telescopes in 1970. It is now the most commonly used tracer of molecular gas in general in the interstellar medium of galaxies, as molecular hydrogen can only be detected using ultraviolet light, which requires space telescopes. Carbon monoxide observations provide much of the information about the molecular clouds in which most stars form.[76]

Beta Pictoris, the second brightest star in the constellation Pictor, shows an excess of infrared emission compared to normal stars of its type, which is caused by large quantities of dust and gas (including carbon monoxide)[77][78] near the star.

Solid carbon monoxide is a component of comets.[79] Halley's Comet is about 15% carbon monoxide.[80] It has also been identified spectroscopy on the surface of Neptune's moon Triton.[81] At room temperature and at atmospheric pressure carbon monoxide is actually only metastable (see Boudouard reaction) and the same is true at low temperatures where CO and CO

2 are solid, but nevertheless it can exist for billions of years in comets. There is very little CO in the atmosphere of Pluto, which seems to have been formed from comets. This may be because there is (or was) liquid water inside Pluto. Carbon monoxide can react with water to form carbon dioxide and hydrogen:

- CO + H2O → H

2 + CO

2

This is called the water-gas shift reaction when occurring in the gas phase, but it can also take place (very slowly) in aqueous solution. If the hydrogen partial pressure is high enough (for instance in an underground sea), formic acid will be formed:

- CO + H2O → HCOOH

These reactions can take place in a few million years even at temperatures such as found on Pluto.[82]

Mining

Miners refer to carbon monoxide as "white damp" or the "silent killer". It can be found in confined areas of poor ventilation in both surface mines and underground mines. The most common sources of carbon monoxide in mining operations are the internal combustion engine and explosives, however in coal mines carbon monoxide can also be found due to the low temperature oxidation of coal.[83]

Production

Many methods have been developed for carbon monoxide's production.[84]

Industrial production

A major industrial source of CO is producer gas, a mixture containing mostly carbon monoxide and nitrogen, formed by combustion of carbon in air at high temperature when there is an excess of carbon. In an oven, air is passed through a bed of coke. The initially produced CO2 equilibrates with the remaining hot carbon to give CO. The reaction of CO2 with carbon to give CO is described as the Boudouard reaction.[85] Above 800 °C, CO is the predominant product:

- CO2 + C → 2 CO (ΔH = 170 kJ/mol)

Another source is "water gas", a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide produced via the endothermic reaction of steam and carbon:

- H2O + C → H2 + CO (ΔH = +131 kJ/mol)

Other similar "synthesis gases" can be obtained from natural gas and other fuels.

Carbon monoxide can also be produced by high-temperature electrolysis of carbon dioxide with solid oxide electrolyzer cells:[86] One method, developed at DTU Energy uses a cerium oxide catalyst and does not have any issues of fouling of the catalyst[87][88]

- 2 CO2 → 2 CO + O2

Carbon monoxide is also a byproduct of the reduction of metal oxide ores with carbon, shown in a simplified form as follows:

- MO + C → M + CO

Carbon monoxide is also produced by the direct oxidation of carbon in a limited supply of oxygen or air.

- 2 C(s) + O2 → 2 CO(g)

Since CO is a gas, the reduction process can be driven by heating, exploiting the positive (favorable) entropy of reaction. The Ellingham diagram shows that CO formation is favored over CO2 in high temperatures.

Laboratory preparation

Carbon monoxide is conveniently produced in the laboratory by the dehydration of formic acid or oxalic acid, for example with concentrated sulfuric acid.[89][90][91] Another method is heating an intimate mixture of powdered zinc metal and calcium carbonate, which releases CO and leaves behind zinc oxide and calcium oxide:

- Zn + CaCO3 → ZnO + CaO + CO

Silver nitrate and iodoform also afford carbon monoxide:

- CHI3 + 3AgNO3 + H2O → 3HNO3 + CO + 3AgI

Finally, metal oxalate salts release CO upon heating, leaving a carbonate as byproduct:

- Na

2C

2O

4 → Na

2CO

3 + CO

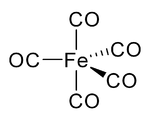

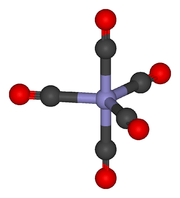

Coordination chemistry

Most metals form coordination complexes containing covalently attached carbon monoxide. Only metals in lower oxidation states will complex with carbon monoxide ligands. This is because there must be sufficient electron density to facilitate back-donation from the metal dxz-orbital, to the π* molecular orbital from CO. The lone pair on the carbon atom in CO, also donates electron density to the dx²−y² on the metal to form a sigma bond. This electron donation is also exhibited with the cis effect, or the labilization of CO ligands in the cis position. Nickel carbonyl, for example, forms by the direct combination of carbon monoxide and nickel metal:

- Ni + 4 CO → Ni(CO)4 (1 bar, 55 °C)

For this reason, nickel in any tubing or part must not come into prolonged contact with carbon monoxide. Nickel carbonyl decomposes readily back to Ni and CO upon contact with hot surfaces, and this method is used for the industrial purification of nickel in the Mond process.[92]

In nickel carbonyl and other carbonyls, the electron pair on the carbon interacts with the metal; the carbon monoxide donates the electron pair to the metal. In these situations, carbon monoxide is called the carbonyl ligand. One of the most important metal carbonyls is iron pentacarbonyl, Fe(CO)5:

Many metal-CO complexes are prepared by decarbonylation of organic solvents, not from CO. For instance, iridium trichloride and triphenylphosphine react in boiling 2-methoxyethanol or DMF to afford IrCl(CO)(PPh3)2.

Metal carbonyls in coordination chemistry are usually studied using infrared spectroscopy.

Organic and main group chemistry

In the presence of strong acids and water, carbon monoxide reacts with alkenes to form carboxylic acids in a process known as the Koch–Haaf reaction.[89] In the Gattermann–Koch reaction, arenes are converted to benzaldehyde derivatives in the presence of AlCl3 and HCl.[90] Organolithium compounds (e.g. butyl lithium) react with carbon monoxide, but these reactions have little scientific use.

Although CO reacts with carbocations and carbanions, it is relatively nonreactive toward organic compounds without the intervention of metal catalysts.[93]

With main group reagents, CO undergoes several noteworthy reactions. Chlorination of CO is the industrial route to the important compound phosgene. With borane CO forms the adduct H3BCO, which is isoelectronic with the acetylium cation [H3CCO]+. CO reacts with sodium to give products resulting from C-C coupling such as sodium acetylenediolate 2Na+

·C

2O2−

2. It reacts with molten potassium to give a mixture of an organometallic compound, potassium acetylenediolate 2K+

·C

2O2−

2, potassium benzenehexolate 6K+

C

6O6−

6,[94] and potassium rhodizonate 2K+

·C

6O2−

6.[95]

The compounds cyclohexanehexone or triquinoyl (C6O6) and cyclopentanepentone or leuconic acid (C5O5), which so far have been obtained only in trace amounts, can be regarded as polymers of carbon monoxide.

At pressures of over 5 gigapascals, carbon monoxide converts into a solid polymer of carbon and oxygen. This is metastable at atmospheric pressure but is a powerful explosive.[96][97]

Uses

Chemical industry

Carbon monoxide is an industrial gas that has many applications in bulk chemicals manufacturing.[98] Large quantities of aldehydes are produced by the hydroformylation reaction of alkenes, carbon monoxide, and H2. Hydroformylation is coupled to the Shell higher olefin process to give precursors to detergents.

Phosgene, useful for preparing isocyanates, polycarbonates, and polyurethanes, is produced by passing purified carbon monoxide and chlorine gas through a bed of porous activated carbon, which serves as a catalyst. World production of this compound was estimated to be 2.74 million tonnes in 1989.[99]

- CO + Cl2 → COCl2

Methanol is produced by the hydrogenation of carbon monoxide. In a related reaction, the hydrogenation of carbon monoxide is coupled to C-C bond formation, as in the Fischer-Tropsch process where carbon monoxide is hydrogenated to liquid hydrocarbon fuels. This technology allows coal or biomass to be converted to diesel.

In the Cativa process, carbon monoxide and methanol react in the presence of a homogeneous Iridium catalyst and hydroiodic acid to give acetic acid. This process is responsible for most of the industrial production of acetic acid.

An industrial scale use for pure carbon monoxide is purifying nickel in the Mond process.

Carbon monoxide can also be used in the water-gas shift reaction to produce hydrogen.

Meat coloring

Carbon monoxide is used in modified atmosphere packaging systems in the US, mainly with fresh meat products such as beef, pork, and fish to keep them looking fresh. The carbon monoxide combines with myoglobin to form carboxymyoglobin, a bright-cherry-red pigment. Carboxymyoglobin is more stable than the oxygenated form of myoglobin, oxymyoglobin, which can become oxidized to the brown pigment metmyoglobin. This stable red color can persist much longer than in normally packaged meat.[100] Typical levels of carbon monoxide used in the facilities that use this process are between 0.4% to 0.5%.

The technology was first given "generally recognized as safe" (GRAS) status by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002 for use as a secondary packaging system, and does not require labeling. In 2004, the FDA approved CO as primary packaging method, declaring that CO does not mask spoilage odor.[101] Despite this ruling, the process remains controversial for fears that it masks spoilage.[102] In 2007, a bill[103] was introduced to the United States House of Representatives to label modified atmosphere carbon monoxide packaging as a color additive, but the bill died in subcommittee. The process is banned in many other countries, including Japan, Singapore, and the European Union.[104][105][106]

Medicine

In biology, carbon monoxide is naturally produced by the action of heme oxygenase 1 and 2 on the heme from hemoglobin breakdown. This process produces a certain amount of carboxyhemoglobin in normal persons, even if they do not breathe any carbon monoxide.

Following the first report that carbon monoxide is a normal neurotransmitter in 1993,[17][18] as well as one of three gases that naturally modulate inflammatory responses in the body (the other two being nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide), carbon monoxide has received a great deal of clinical attention as a biological regulator. In many tissues, all three gases are known to act as anti-inflammatories, vasodilators, and encouragers of neovascular growth.[19] However, the issues are complex, as neovascular growth is not always beneficial, since it plays a role in tumor growth, and also the damage from wet macular degeneration, a disease for which smoking (a major source of carbon monoxide in the blood, several times more than natural production) increases the risk from 4 to 6 times.

There is a theory that, in some nerve cell synapses, when long-term memories are being laid down, the receiving cell makes carbon monoxide, which back-transmits to the transmitting cell, telling it to transmit more readily in future. Some such nerve cells have been shown to contain guanylate cyclase, an enzyme that is activated by carbon monoxide.[18]

Studies involving carbon monoxide have been conducted in many laboratories throughout the world for its anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective properties. These properties have potential to be used to prevent the development of a series of pathological conditions including ischemia reperfusion injury, transplant rejection, atherosclerosis, severe sepsis, severe malaria, or autoimmunity. Clinical tests involving humans have been performed, however the results have not yet been released.[20]

Metallurgy

Carbon monoxide is a strong reductive agent, and whilst not known, it has been used in pyrometallurgy to reduce metals from ores since ancient times. Carbon monoxide strips oxygen off metal oxides, reducing them to pure metal in high temperatures, forming carbon dioxide in the process. Carbon monoxide is not usually supplied as is, in gaseous phase, in the reactor, but rather it is formed in high temperature in presence of oxygen-carrying ore, carboniferous agent such as coke and high temperature. The blast furnace process is a typical example of a process of reduction of metal from ore with carbon monoxide.

Lasers

Carbon monoxide has also been used as a lasing medium in high-powered infrared lasers.[107]

Niche uses

Carbon monoxide has been proposed for use as a fuel on Mars. Carbon monoxide/oxygen engines have been suggested for early surface transportation use as both carbon monoxide and oxygen can be straightforwardly produced from the atmosphere of Mars by zirconia electrolysis, without using any Martian water resources to obtain hydrogen, which would be needed to make methane or any hydrogen-based fuel.[108] Likewise, blast furnace gas collected at the top of blast furnace, still contains some 10% to 30% of carbon monoxide, and is used as fuel on Cowper stoves and on Siemens-Martin furnaces on open hearth steelmaking.

See also

- Carbon monoxide (data page) – Chemical data page

- Breath carbon monoxide

- Carbon monoxide detector – A device that measures carbon monoxide (CO)

- Criteria air pollutants

- List of highly toxic gases – Wikipedia list article

- Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society – US based organisation for research and education in hyperbaric physiology and medicine. – hyperbaric treatment for CO poisoning

- Rubicon Foundation – Non-profit organization for promoting research and information access for underwater diving research articles on CO poisoning

References

- Richard, Pohanish (2012). Sittig's Handbook of Toxic and Hazardous Chemicals and Carcinogens (2 ed.). Elsevier. p. 572. ISBN 978-1-4377-7869-4. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "Carbon monoxide". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0105". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- GOV, NOAA Office of Response and Restoration, US. "CARBON MONOXIDE - CAMEO Chemicals - NOAA". cameochemicals.noaa.gov.

- Penney, David G. (2000) Carbon Monoxide Toxicity, CRC Press, p. 5, ISBN 0-8493-2065-8.

- Cruickshank, W. (1801) "Some observations on different hydrocarbons and combinations of carbon with oxygen, etc. in reply to some of Dr. Priestley's late objections to the new system of chemistry," Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts [a.k.a. Nicholson's Journal], 1st series, 5 : 1–9.

- Cruickshank, W. (1801) "Some additional observations on hydrocarbons, and the gaseous oxide of carbon," Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts, 1st series, 5 : 201–211.

- Waring, Rosemary H.; Steventon, Glyn B.; Mitchell, Steve C. (2007). Molecules of death. Imperial College Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-86094-814-5.

- Kitchen, Martin (2006). A history of modern Germany, 1800–2000. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 323. ISBN 978-1-4051-0041-0.

- Thompson, Mike. Carbon Monoxide – Molecule of the Month, Winchester College, UK.

- Ayres, Robert U.; Ayres, Edward H. (2009). Crossing the Energy Divide: Moving from Fossil Fuel Dependence to a Clean-Energy Future. Wharton School Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-13-701544-3.

- Kinetic studies of propane oxidation on Mo and V based mixed oxide catalysts (PDF). 2011.

- Amakawa, Kazuhiko; Kolen'Ko, Yury V.; Villa, Alberto; Schuster, Manfred E/; Csepei, Lénárd-István; Weinberg, Gisela; Wrabetz, Sabine; Naumann d'Alnoncourt, Raoul; Girgsdies, Frank; Prati, Laura; Schlögl, Robert; Trunschke, Annette (26 April 2013). "Multifunctionality of Crystalline MoV(TeNb) M1 Oxide Catalysts in Selective Oxidation of Propane and Benzyl Alcohol". ACS Catalysis. 3 (6): 1103–1113. doi:10.1021/cs400010q.

- Naumann d'Alnoncourt, Raoul; Csepei, Lénárd-István; Hävecker, Michael; Girgsdies, Frank; Schuster, Manfred E.; Schlögl, Robert; Trunschke, Annette (March 2014). "The reaction network in propane oxidation over phase-pure MoVTeNb M1 oxide catalysts" (PDF). Journal of Catalysis. 311: 369–385. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2013.12.008. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0014-F434-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-15. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- Hävecker, Michael; Wrabetz, Sabine; Kröhnert, Jutta; Csepei, Lenard-Istvan; Naumann d'Alnoncourt, Raoul; Kolen'Ko, Yury V.; Girgsdies, Frank; Schlögl, Robert; Trunschke, Annette (January 2012). "Surface chemistry of phase-pure M1 MoVTeNb oxide during operation in selective oxidation of propane to acrylic acid" (PDF). Journal of Catalysis. 285 (1): 48–60. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2011.09.012. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-1BEB-F. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-30. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- Weinstock, B.; Niki, H. (1972). "Carbon Monoxide Balance in Nature". Science. 176 (4032): 290–2. Bibcode:1972Sci...176..290W. doi:10.1126/science.176.4032.290. PMID 5019781.

- Verma, A; Hirsch, D.; Glatt, C.; Ronnett, G.; Snyder, S. (1993). "Carbon monoxide: A putative neural messenger". Science. 259 (5093): 381–4. Bibcode:1993Sci...259..381V. doi:10.1126/science.7678352. PMID 7678352.

- Kolata, Gina (January 26, 1993). "Carbon Monoxide Gas Is Used by Brain Cells As a Neurotransmitter". The New York Times. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- Li, L; Hsu, A; Moore, PK (2009). "Actions and interactions of nitric oxide, carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulphide in the cardiovascular system and in inflammation—a tale of three gases!". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 123 (3): 386–400. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.005. PMID 19486912.

- Johnson, Carolyn Y. (October 16, 2009). "Poison gas may carry a medical benefit". The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- Tift, M; Ponganis, P; Crocker, D (2014). "Elevated carboxyhemoglobin in a marine mammal, the northern elephant seal". Journal of Experimental Biology. 217 (10): 1752–1757. doi:10.1242/jeb.100677. PMID 24829326.

- Tift, M; Ponganis, P (2019). "Time Domains of Hypoxia Adaptation-Elephant Seals Stand Out Among Divers". Frontiers in Physiology. 10. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00677. PMID 31214049.

- Gilliam, O. R.; Johnson, C. M.; Gordy, W. (1950). "Microwave Spectroscopy in the Region from Two to Three Millimeters". Physical Review. 78 (2): 140–144. Bibcode:1950PhRv...78..140G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.78.140.

- Haynes, William M. (2010). Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (91 ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 9–33. ISBN 978-1439820773.

- Haynes, William M. (2010). Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (91 ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 9–39. ISBN 978-1439820773.

- Common Bond Energies (D) and Bond Lengths (r). wiredchemist.com

- Vidal, C. R. (28 June 1997). "Highly Excited Triplet States of Carbon Monoxide". Archived from the original on 2006-08-28. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- Scuseria, Gustavo E.; Miller, Michael D.; Jensen, Frank; Geertsen, Jan (1991). "The dipole moment of carbon monoxide". J. Chem. Phys. 94 (10): 6660. Bibcode:1991JChPh..94.6660S. doi:10.1063/1.460293.

- Martinie, Ryan J.; Bultema, Jarred J.; Vander Wal, Mark N.; Burkhart, Brandon J.; Vander Griend, Douglas A.; DeKock, Roger L. (2011-08-01). "Bond Order and Chemical Properties of BF, CO, and N2". Journal of Chemical Education. 88 (8): 1094–1097. Bibcode:2011JChEd..88.1094M. doi:10.1021/ed100758t. ISSN 0021-9584. S2CID 11905354.

- 1925-, Ulrich, Henri (2009). Cumulenes in click reactions. Wiley InterScience (Online service). Chichester, U.K.: Wiley. p. 45. ISBN 9780470747957. OCLC 476311784.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Lupinetti, Anthony J.; Fau, Stefan; Frenking, Gernot; Strauss, Steven H. (1997). "Theoretical Analysis of the Bonding between CO and Positively Charged Atoms". J. Phys. Chem. A. 101 (49): 9551–9559. Bibcode:1997JPCA..101.9551L. doi:10.1021/jp972657l.

- Blanco, Fernando; Alkorta, Ibon; Solimannejad, Mohammad; Elguero, Jose (2009). "Theoretical Study of the 1:1 Complexes between Carbon Monoxide and Hypohalous Acids". J. Phys. Chem. A. 113 (13): 3237–3244. Bibcode:2009JPCA..113.3237B. doi:10.1021/jp810462h. hdl:10261/66300. PMID 19275137.

- Meerts, W; De Leeuw, F.H.; Dymanus, A. (1 June 1977). "Electric and magnetic properties of carbon monoxide by molecular-beam electric-resonance spectroscopy". Chemical Physics. 22 (2): 319–324. Bibcode:1977CP.....22..319M. doi:10.1016/0301-0104(77)87016-X.

- Stefan, Thorsten; Janoschek, Rudolf (2000). "How relevant are S=O and P=O Double Bonds for the Description of the Acid Molecules H2SO3, H2SO4, and H3PO3, respectively?". Journal of Molecular Modeling. 6 (2): 282–288. doi:10.1007/PL00010730.

- Omaye ST (2002). "Metabolic modulation of carbon monoxide toxicity". Toxicology. 180 (2): 139–150. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00387-6. PMID 12324190.

- Tikuisis, P; Kane, DM; McLellan, TM; Buick, F; Fairburn, SM (1992). "Rate of formation of carboxyhemoglobin in exercising humans exposed to carbon monoxide". Journal of Applied Physiology. 72 (4): 1311–9. doi:10.1152/jappl.1992.72.4.1311. PMID 1592720.

- "OSHA CO guidelines". OSHA. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- Blumenthal, Ivan (1 June 2001). "Carbon monoxide poisoning". J R Soc Med. 94 (6): 270–272. doi:10.1177/014107680109400604. PMC 1281520. PMID 11387414.

- Ganong, William F (2005). "37". Review of medical physiology (22 ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 684. ISBN 978-0-07-144040-0. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- Prockop LD, Chichkova RI (2007). "Carbon monoxide intoxication: an updated review". J Neurol Sci. 262 (1–2): 122–130. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.037. PMID 17720201.

- Tucker Blackburn, Susan (2007). Maternal, fetal, & neonatal physiology: a clinical perspective. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 325. ISBN 978-1-4160-2944-1.

- Wu, L; Wang, R (December 2005). "Carbon Monoxide: Endogenous Production, Physiological Functions, and Pharmacological Applications". Pharmacol Rev. 57 (4): 585–630. doi:10.1124/pr.57.4.3. PMID 16382109. S2CID 17538129.

- Wallace JL, Ianaro A, Flannigan KL, Cirino G (2015). "Gaseous mediators in resolution of inflammation". Seminars in Immunology. 27 (3): 227–33. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2015.05.004. PMID 26095908.

- Uehara EU, Shida Bde S, de Brito CA (2015). "Role of nitric oxide in immune responses against viruses: beyond microbicidal activity". Inflammation Research. 64 (11): 845–52. doi:10.1007/s00011-015-0857-2. PMID 26208702.

- Nakahira K, Choi AM (2015). "Carbon monoxide in the treatment of sepsis". American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 309 (12): L1387–93. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00311.2015. PMC 4683310. PMID 26498251.

- Shinohara M, Serhan CN (2016). "Novel Endogenous Proresolving Molecules:Essential Fatty Acid-Derived and Gaseous Mediators in the Resolution of Inflammation". Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 23 (6): 655–64. doi:10.5551/jat.33928. PMID 27052783.

- Olas, Beata (25 April 2014). "Carbon monoxide is not always a poison gas for human organism: Physiological and pharmacological features of CO". Chemico-Biological Interactions. 222 (5 October 2014): 37–43. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2014.08.005. PMID 25168849.

- Thauer, R. K. (1998). "Biochemistry of methanogenesis: a tribute to Marjory Stephenson. 1998 Marjory Stephenson Prize Lecture" (Free). Microbiology. 144 (9): 2377–2406. doi:10.1099/00221287-144-9-2377. PMID 9782487.

- Hogan, C. Michael (2010). "Extremophile" in E. Monosson and C. Cleveland (eds.). Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment, Washington, DC

- "Martian life must be rare as free energy source remains untapped". New Scientist. May 13, 2017.

- Jaouen, G., ed. (2006). Bioorganometallics: Biomolecules, Labeling, Medicine. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-30990-0.

- Roberts, G. P.; Youn, H.; Kerby, R. L. (2004). "CO-Sensing Mechanisms". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 68 (3): 453–473. doi:10.1128/MMBR.68.3.453-473.2004. PMC 515253. PMID 15353565.

- Global Maps. Carbon Monoxide. earthobservatory.nasa.gov

- Source for figures: Carbon dioxide, NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory, (updated 2010.06). Methane, IPCC TAR table 6.1, (updated to 1998). The NASA total was 17 ppmv over 100%, and CO2 was increased here by 15 ppmv. To normalize, N2 should be reduced by about 25 ppmv and O2 by about 7 ppmv.

- Committee on Medical and Biological Effects of Environmental Pollutants (1977). Carbon Monoxide. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-309-02631-4.

- Green W. "An Introduction to Indoor Air Quality: Carbon Monoxide (CO)". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- Gosink, Tom (1983-01-28). "What Do Carbon Monoxide Levels Mean?". Alaska Science Forum. Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Archived from the original on 2008-12-25. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- Singer, Siegfried Fred (1975). The Changing Global Environment. Springer. p. 90. ISBN 978-9027704023.

- "Carbon Monoxide Poisoning: Vehicles (AEN-208)". www.abe.iastate.edu. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- Gosink T (January 28, 1983). "What Do Carbon Monoxide Levels Mean?". Alaska Science Forum. Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Archived from the original on December 25, 2008. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- Seinfeld, John; Pandis, Spyros (2006). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-72018-8.

- Sigel, Astrid; Sigel, Roland K. O. (2009). Metal-Carbon Bonds in Enzymes and Cofactors. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-84755-915-9.

- White, James Carrick; et al. (1989). Global climate change linkages: acid rain, air quality, and stratospheric ozone. Springer. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-444-01515-0.

- Drummond, James (February 2, 2018). "MOPITT, Atmospheric Pollution, and Me: A Personal Story". Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- Pommier, M.; Law, K. S.; Clerbaux, C.; Turquety, S.; Hurtmans, D.; Hadji-Lazaro, J.; Coheur, P.-F.; Schlager, H.; Ancellet, G.; Paris, J.-D.; Nédélec, P.; Diskin, G. S.; Podolske, J. R.; Holloway, J. S.; Bernath, P. (2010). "IASI carbon monoxide validation over the Arctic during POLARCAT spring and summer campaigns". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 10 (21): 10655–10678. Bibcode:2010ACP....1010655P. doi:10.5194/acp-10-10655-2010.

- Pommier, M.; McLinden, C. A.; Deeter, M. (2013). "Relative changes in CO emissions over megacities based on observations from space". Geophysical Research Letters. 40 (14): 3766. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40.3766P. doi:10.1002/grl.50704.

- Reeves, Claire E.; Penkett, Stuart A.; Bauguitte, Stephane; Law, Kathy S.; Evans, Mathew J.; Bandy, Brian J.; Monks, Paul S.; Edwards, Gavin D.; Phillips, Gavin; Barjat, Hannah; Kent, Joss; Dewey, Ken; Schmitgen, Sandra; Kley, Dieter (2002). "Potential for photochemical ozone formation in the troposphere over the North Atlantic as derived from aircraft observationsduring ACSOE". Journal of Geophysical Research. 107 (D23): 4707. Bibcode:2002JGRD..107.4707R. doi:10.1029/2002JD002415.

- Ozone and other photochemical oxidants. National Academies. 1977. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-309-02531-7.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, Carbon Monoxide Questions and Answers Archived 2010-01-09 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 2009-12-04

- "Tracking Carbon Monoxide". Environmental Public Health Tracking – Florida Dept. of Health. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

- "AAPCC Annual Data Reports 2007". American Association of Poison Control Centers.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network, Carbon Monoxide Poisoning, accessed 2009-12-04

- "Carbon Monoxide (Blood) - Health Encyclopedia - University of Rochester Medical Center". www.urmc.rochester.edu.

- Roth D.; Herkner H.; Schreiber W.; Hubmann N.; Gamper G.; Laggner A.N.; Havel C. (2011). "Accuracy of Noninvasive Multiwave Pulse Oximetry Compared With Carboxyhemoglobin From Blood Gas Analysis in Unselected Emergency Department Patients" (PDF). Annals of Emergency Medicine. 58 (1): 74–9. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.12.024. PMID 21459480.

- Combes, Françoise (1991). "Distribution of CO in the Milky Way". Annual Review of Astronomy & Astrophysics. 29: 195–237. Bibcode:1991ARA&A..29..195C. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.29.090191.001211.

- Khan, Amina. "Did two planets around nearby star collide? Toxic gas holds hints". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- Dent, W.R.F.; Wyatt, M.C.;Roberge, A.; Augereau, J.-C.; Casassus, S.;Corder, S.; Greaves, J.S.; de Gregorio-Monsalvo, I; Hales, A.; Jackson, A.P.; Hughes, A. Meredith; Lagrange, A.-M; Matthews, B.; Wilner, D. (March 6, 2014). "Molecular Gas Clumps from the Destruction of Icy Bodies in the β Pictoris Debris Disk". Science. 343 (6178): 1490–1492. arXiv:1404.1380. Bibcode:2014Sci...343.1490D. doi:10.1126/science.1248726. PMID 24603151. Retrieved March 9, 2014.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Greenberg, J. Mayo (1998). "Making a comet nucleus". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 330: 375. Bibcode:1998A&A...330..375G.

- Yeomans, Donald K. (2005). "Comets (World Book Online Reference Center 125580)". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 April 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- Lellouch, E.; de Bergh, C.; Sicardy, B.; Ferron, S.; Käufl, H.-U. (2010). "Detection of CO in Triton's atmosphere and the nature of surface-atmosphere interactions". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 512: L8. arXiv:1003.2866. Bibcode:2010A&A...512L...8L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014339. ISSN 0004-6361.

- Christopher Glein and Hunter Waite (May 11, 2018). "Primordial N2 provides a cosmo chemical explanation for the existence of Sputnik Planitia, Pluto". Icarus. 313: 79–92. arXiv:1805.09285. Bibcode:2018Icar..313...79G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.05.007.

- "MSHA - Occupational Illness and Injury Prevention Program - Health Topics - Carbon Monoxide". arlweb.msha.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-12-31. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. "Inorganic Chemistry" Academic Press: San Diego, 200. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- Higman, C; van der Burgt, M (2003). Gasification. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7506-7707-3.

- Zheng, Yun; Wang, Jianchen; Yu, Bo; Zhang, Wenqiang; Chen, Jing; Qiao, Jinli; Zhang, Jiujun (2017). "A review of high temperature co-electrolysis of H O and CO to produce sustainable fuels using solid oxide electrolysis cells (SOECs): advanced materials and technology". Chem. Soc. Rev. 46 (5): 1427–1463. doi:10.1039/C6CS00403B. PMID 28165079.

- New route to carbon-neutral fuels from carbon dioxide discovered by Stanford-DTU team

- Selective high-temperature CO2 electrolysis enabled by oxidized carbon intermediates

- Koch, H.; Haaf, W. (1973). "1-Adamantanecarboxylic Acid". Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, 5, p. 20

- Coleman, G. H.; Craig, David (1943). "p-Tolualdehyde". Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, 2, p. 583

- Brauer, Georg (1963). Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry Vol. 1, 2nd Ed. Newyork: Academic Press. p. 646. ISBN 978-0121266011.

- Mond L, Langer K, Quincke F (1890). "Action of carbon monoxide on nickel". Journal of the Chemical Society. 57: 749–753. doi:10.1039/CT8905700749.

- Chatani, N.; Murai, S. "Carbon Monoxide" in Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (Ed: L. Paquette) 2004, J. Wiley & Sons, New York. doi:10.1002/047084289

- Büchner, W.; Weiss, E. (1964). "Zur Kenntnis der sogenannten "Alkalicarbonyle" IV[1] Über die Reaktion von geschmolzenem Kalium mit Kohlenmonoxid". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 47 (6): 1415–1423. doi:10.1002/hlca.19640470604.

- Fownes, George (1869). A Manual of elementary chemistry. H.C. Lea. p. 678.

- Katz, Allen I.; Schiferl, David; Mills, Robert L. (1984). "New phases and chemical reactions in solid carbon monoxide under pressure". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 88 (15): 3176–3179. doi:10.1021/j150659a007.

- Evans, W. J.; Lipp, M. J.; Yoo, C.-S.; Cynn, H.; Herberg, J. L.; Maxwell, R. S.; Nicol, M. F. (2006). "Pressure-Induced Polymerization of Carbon Monoxide: Disproportionation and Synthesis of an Energetic Lactonic Polymer". Chemistry of Materials. 18 (10): 2520–2531. doi:10.1021/cm0524446.

- Elschenbroich, C.; Salzer, A. (2006). Organometallics: A Concise Introduction (2nd ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-28165-7.

- Wolfgang Schneider; Werner Diller. "Phosgene". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_411.

- Sorheim, S; Nissena, H; Nesbakken, T (1999). "The storage life of beef and pork packaged in an atmosphere with low carbon monoxide and high carbon dioxide". Journal of Meat Science. 52 (2): 157–164. doi:10.1016/S0309-1740(98)00163-6. PMID 22062367.

- Eilert EJ (2005). "New packaging technologies for the 21st century". Journal of Meat Science. 71 (1): 122–127. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.04.003. PMID 22064057.

- Huffman, Randall D. "Low-Oxygen Packaging with CO: A Study in Food Politics That Warrants Peer Review". FoodSafetyMagazine.com. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- "Carbon Monoxide Treated Meat, Poultry, and Seafood Safe Handling, Labeling, and Consumer Protection Act (Introduced in House)". The Library of Congress. 2007-07-19.

- "Proof in the Pink? Meat Treated to Give It Fresh Look". ABC News. November 14, 2007. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- Carbon Monoxide in Meat Packaging: Myths and Facts. American Meat Institute. 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- "CO in packaged meat". Carbon Monoxide Kills Campaign. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- Ionin, A.; Kinyaevskiy, I.; Klimachev, Y.; Kotkov, A.; Kozlov, A. (2012). "Novel mode-locked carbon monoxide laser system achieves high accuracy". SPIE Newsroom. doi:10.1117/2.1201112.004016. S2CID 112510554.

- Landis (2001). "Mars Rocket Vehicle Using In Situ Propellants". Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. 38 (5): 730–735. Bibcode:2001JSpRo..38..730L. doi:10.2514/2.3739.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carbon monoxide. |

- Global map of carbon monoxide distribution

- Explanation of the structure

- Carbon Monoxide Safety Association

- International Chemical Safety Card 0023

- CDC NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards: Carbon monoxide—National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- External MSDS data sheet

- Carbon Monoxide Detector Placement

- Carbon Monoxide Purification Process

- Microscale Gas Chemistry Experiments with Carbon Monoxide

- "Instant insight: Don't blame the messenger". Chemical Biology (11: Research News). 18 October 2007. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 27 October 2019. Outlining the physiology of carbon monoxide from the Royal Society of Chemistry.