Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (/ˌɡwɑːdəˈluːp/, French: [ɡwad(ə)lup] (![]()

Guadeloupe Gwadloup (Guadeloupean Creole French) | |

|---|---|

Overseas region and department | |

| Overseas department of Guadelope Département d’Outre-Mer de la Guadeloupe (French) | |

.jpg) Beach in St. Anne, Guadeloupe | |

| |

| Country | |

| Prefecture | Basse-Terre |

| Departments | 1 |

| Government | |

| • President of the Regional Council | Ary Chalus |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,628 km2 (629 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 16th region |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

| • Total | 395,700[1] |

| Demonym(s) | Guadeloupean |

| Time zone | UTC-04:00 (AST) |

| ISO 3166 code | |

| GDP (2014)[1] | Ranked 25th |

| Total | €8.1 billion (US$10.3 bn) |

| Per capita | €19,810 (US$25,479) |

| NUTS Region | FRA |

| Website | www |

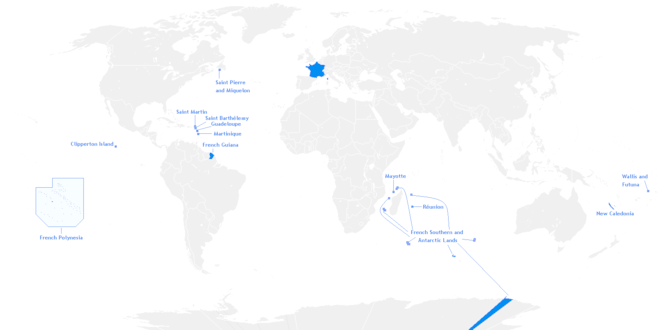

Like the other overseas departments, it is an integral part of France. As a constituent territory of the European Union and the Eurozone, the euro is its official currency and any European Union citizen is free to settle and work there indefinitely. As an overseas department, however, it is not part of the Schengen Area. The region formerly included Saint Barthélemy and Saint Martin, which were detached from Guadeloupe in 2007 following a 2003 referendum.

The official language is French; Antillean Creole is also spoken.[2][4]

Etymology

The archipelago was called Karukera (or "The Island of Beautiful Waters") by the native Arawak people.[2]

Christopher Columbus named the island Santa María de Guadalupe in 1493 after the Our Lady of Guadalupe, a shrine to the Virgin Mary venerated in the Spanish town of Guadalupe, Extremadura.[2] Upon becoming a French colony, the Spanish name was retained though altered to French orthography and phonology. The islands are locally known as Gwada.[5]

History

Pre-colonial era

The islands were first populated by indigenous peoples of the Americas, possibly as far back as 3000 BC.[6][7][8] The Arawak people are the first identifiable group; however, they were later displaced circa 1400 AD by Kalina-Carib peoples.[2]

Arrival of Europeans

Christopher Columbus was the first European to see Guadeloupe, landing in November 1493 and giving it its current name.[2] Several attempts at colonisation by the Spanish in the 16th century failed due to attacks from the native Caribs peoples.[2] In 1626 the French under Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc began to take an interest in Guadeloupe, expelling Spanish settlers.[2] The Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique settled in Guadeloupe in 1635, under the direction of Charles Liénard de L'Olive and Jean du Plessis d'Ossonville; they formally took possession of the island for France and brought in French farmers to colonise the land. This led to the death of many Caribs by disease and violence.[9] By 1640, however, the Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique had gone bankrupt, and they thus sold Guadeloupe to Charles Houël du Petit Pré who began plantation agriculture, with the first African slaves arriving in 1650.[10][11] Ownership of the island then passed to the French West India Company before it was annexed to France in 1674 under the tutelage of their Martinique colony.[2] Institutionalised slavery, enforced by the Code Noir from 1685, led to a booming sugar plantation economy.[12]

18th-19th centuries

During the Seven Years' War the British occupied Guadeloupe from the time of 1759 British Invasion of Guadeloupe until the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[2] During this time Pointe-à-Pitre became a major harbour, and markets in Britain's North American colonies were opened to Guadeloupean sugar which was traded for cheap food and timber. The economy expanded quickly, creating vast wealth for the European colonists.[13] During this time about 18,000 slaves were imported to Guadeloupe.[10] So prosperous was Guadeloupe at the time that under the 1763 Treaty of Paris France forfeited its Canadian colonies in exchange for Guadeloupe.[14] Coffee planting began in the late 1720s,[15] also worked by slaves, and by 1775 cocoa had also become a major export product.[10]

The 1789 French Revolution brought chaos to Guadeloupe. Under new revolutionary law free people of colour were entitled to equal rights. Taking advantage of the anarchic political situation, Britain invaded Guadeloupe in 1794, to which the French responded by sending in soldiers led by Victor Hugues, who retook the lands and abolished slavery.[2] In the Reign of Terror that followed more than 1,000 colonists were killed.[13]

In 1802 the First French Empire reinstated the pre-revolutionary government and slavery, prompting a slave rebellion led by Louis Delgrès.[2] The French authorities responded quickly, culminating in the Battle of Matouba on 28 May 1802. Realising they had no chance of success, Delgrès and his followers committed mass suicide by deliberately exploding their gunpowder stores.[16][17] In 1810 the British again seized the island, handing it over to Sweden in 1813.[18]

In the Treaty of Paris of 1814, Sweden ceded Guadeloupe to France, giving rise to the Guadeloupe Fund. In 1815 the Treaty of Vienna definitively acknowledged French control of Guadeloupe.[2][10]

Slavery was abolished in the French Empire in 1848.[2] From 1854 indentured labourers from the French colony of Pondicherry in India were brought in. Emancipated slaves had the vote from 1849, but French nationality and the vote was not granted to Indian citizens until 1923, thanks largely to the efforts of Henry Sidambarom.[19]

20th-21st centuries

In 1936 Félix Éboué became the first black governor of Guadeloupe.[20] During the Second World War Guadeloupe initially came under the control of the Vichy government, later joining Free France in 1943.[2] In 1946, the colony of Guadeloupe became an overseas department of France.[2]

Tensions arose in the post-war era over the social structure of Guadeloupe and its relationship with mainland France. The 'Massacre of St Valentine' occurred in 1952, when striking factory workers in Le Moule were shot at by the Compagnies républicaines de sécurité, resulting in four deaths.[21][22][23] In May 1967 racial tensions exploded into rioting following a racist attack on a black Guadeloupean, resulting in eight deaths.[24][25][26]

An independence movement grew in the 1970s, prompting France to declare Guadeloupe a French region in 1974.[2] The Union populaire pour la libération de la Guadeloupe (UPLG) campaigned for complete independence, and by the 1980s the situation had turned violent with the actions of groups such as Groupe de libération armée (GLA) and Alliance révolutionnaire caraïbe (ARC).

Greater autonomy was granted to Guadeloupe in 2000.[2] Through a referendum in 2003, Saint-Martin and Saint Barthélemy voted to separate from the administrative jurisdiction of Guadeloupe, this being fully enacted by 2007.[2]

In January 2009, labour unions and others known as the Liyannaj Kont Pwofitasyon went on strike for more pay.[27] Strikers were angry with low wages, the high cost of living, high levels of poverty relative to mainland France and levels of unemployment that are amongst the worst in the European Union.[28] The situation quickly escalated, exacerbated by what was seen as an ineffectual response by the French government, turning violent and prompting the deployment of extra police after a union leader (Jacques Bino) was shot and killed.[29] The strike lasted 44 days and had also inspired similar actions on nearby Martinique. President Nicolas Sarkozy later visited the island, promising reform.[30] Tourism suffered greatly during this time and affected the 2010 tourist season as well.

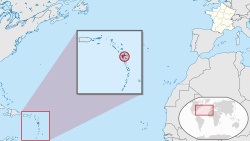

Geography

Guadeloupe is an archipelago of more than 12 islands, as well as islets and rocks situated where the northeastern Caribbean Sea meets the western Atlantic Ocean.[2] It is located in the Leeward Islands in the northern part of the Lesser Antilles, a partly volcanic island arc. To the north lies Antigua and Barbuda and the British Oversea Territory of Montserrat, with Dominica lying to the south.

The main two islands are Basse-Terre (west) and Grande-Terre (east), which form a butterfly shape as viewed from above, the two 'wings' of which are separated by the Grand Cul-de-Sac Marin, Rivière Salée and Petit Cul-de-Sac Marin. More than half of Guadeloupe's land surface consists of the 847.8 km2 Basse-Terre.[31] The island is mountainous, containing such peaks as Mount Sans Toucher (4,442 feet; 1,354 metres) and Grande Découverte (4,143 feet; 1,263 metres), culminating in the active volcano La Grande Soufrière, the highest mountain peak in the Lesser Antilles with an elevation of 1,467 metres (4,813 ft).[2][32] In contrast Grande-Terre is mostly flat, with rocky coasts to the north, irregular hills at the centre, mangrove at the southwest, and white sand beaches sheltered by coral reefs along the southern shore.[33] This is where the main tourist resorts are found.[34]

Marie-Galante is the third-largest island, followed by La Désirade, a north-east slanted limestone plateau, the highest point of which is 275 metres (902 ft). To the south lies the Îles de Petite-Terre, which are two islands (Terre de Haut and Terre de Bas) totalling 2 km2.[34]

Les Saintes is an archipelago of eight islands of which two, Terre-de-Bas and Terre-de-Haut are inhabited. The landscape is similar to that of Basse-Terre, with volcanic hills and irregular shoreline with deep bays.

There are numerous other smaller islands, most notably Tête à l'Anglais, Îlet à Kahouanne, Îlet à Fajou, Îlet Macou, Îlet aux Foux, Îlets de Carénage, La Biche, Îlet Crabière, Îlets à Goyaves, Îlet à Cochons, Îlet à Boissard, Îlet à Chasse and Îlet du Gosier.

Geology

Basse-Terre is a volcanic island. The Lesser Antilles are at the outer edge of the Caribbean Plate, and Guadeloupe is part of the outer arc of the Lesser Antilles Volcanic Arc. Many of the islands were formed as a result of the subduction of oceanic crust of the Atlantic Plate under the Caribbean Plate in the Lesser Antilles subduction zone. This process is ongoing and is responsible for volcanic and earthquake activity in the region. Guadeloupe was formed from multiple volcanoes, of which only la Soufriere is not extinct.[35] Its last eruption was in 1976, and led to the evacuation of the southern part of Basse-Terre. 73,600 people were displaced over a course of three and a half months following the eruption.

K–Ar dating indicates that the three northern massifs on Basse-Terre Island are 2.79 million years old. Sections of volcanoes collapsed and eroded within the last 650,000 years, after which the Sans Toucher volcano grew in the collapsed area. Volcanoes in the north of Basse-Terre Island mainly produced andesite and basaltic andesite.[36] There are several beaches of dark or "black" sand.[34]

La Désirade, east of the main islands has a basement from the Mesozoic, overlaid with thick limestones from the Pliocene to Quaternary periods.[37]

Grande-Terre and Marie-Galante have basements probably composed of volcanic units of Eocene to Oligocene, but there are no visible outcrops. On Grande-Terre, the overlying carbonate platform is 120 metres thick.[37]

Climate

The islands are part of the Leeward Islands, so called because they are downwind of the prevailing trade winds, which blow out of the northeast.[2][38] This was significant in the days of sailing ships. Grande-Terre is so named because it is on the eastern, or windward side, exposed to the Atlantic winds. Basse-Terre is so named because it is on the leeward south-west side and sheltered from the winds. Guadeloupe has a tropical climate tempered by maritime influences and the Trade Winds. There are two seasons, the dry season called "Lent" from January to June, and the wet season called "winter", from July to December.[2]

The island is vulnerable to hurricanes - among the storms to make landfall on the islands are:[31] Hurricane Cleo in 1964, Hurricane Hugo in 1989, and Hurricane Maria in 2017.[39][40][41]

| Climate data for Guadeloupe | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.1 (84.4) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.5 (86.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.5 (76.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

25.2 (77.4) |

26.3 (79.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

22.1 (71.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 84 (3.3) |

64 (2.5) |

73 (2.9) |

123 (4.8) |

148 (5.8) |

118 (4.6) |

150 (5.9) |

198 (7.8) |

236 (9.3) |

228 (9.0) |

220 (8.7) |

137 (5.4) |

1,779 (70.0) |

| Average precipitation days | 15.0 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 11.6 | 13.6 | 12.8 | 15.4 | 16.2 | 16.6 | 18.1 | 16.6 | 15.7 | 174.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 235.6 | 229.1 | 232.5 | 240.0 | 244.9 | 237.0 | 244.9 | 248.0 | 216.0 | 217.0 | 207.0 | 223.2 | 2,775.2 |

| Source: Hong Kong Observatory[42] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

With fertile volcanic soils, heavy rainfall and a warm climate, vegetation on Basse-Terre is lush.[31] Most of the islands' forests are on Basse-Terre, containing such species as mahogany, ironwood and chestnut trees.[2] Mangrove swamps line the Salée River.[2] Much of the forest on Grande-Terre has been cleared, with only a few small patches remaining.[2]

Numerous mammal species live on the islands, notably raccoons, agouti and mongoose.[2] Bird species include the Guadeloupe woodpecker, Antillean nighthawk and monk parakeets.[2] The waters of the islands support a rich variety of marine life.[2]

Demographics

Guadeloupe recorded a population of 402,119 in the 2013 census.[43] The population is mainly of Afro-Caribbean or mixed Creole, white European, Indian (Tamil, Telugu, and other South Indians), Lebanese, Syrians, and Chinese. There is also a substantial population of Haitians in Guadeloupe who work mainly in construction and as street vendors.[44] Basse-Terre is the political capital; however, the largest city and economic hub is Pointe-à-Pitre.[2]

The population of Guadeloupe has been stable recently, with a net increase of only 335 people between the 2008 and 2013 censuses.[45] In 2012 the average population density in Guadeloupe was 247.7 inhabitants for every square kilometre, which is very high in comparison to the whole France's 116.5 inhabitants for every square kilometre. One third of the land is devoted to agriculture and all mountains are uninhabitable; this lack of space and shelter makes the population density even higher.

Major urban areas

| Rank | Urban Area | Pop. (08) | Pop. (99) | Δ Pop | Activities | Island |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pointe-à-Pitre | 132,884 | 132,751 | economic center | Grande-Terre and Basse-Terre | |

| 2 | Basse-Terre | 37,455 | 36,126 | administrative center | Basse-Terre | |

| 3 | Sainte-Anne | 23,457 | 20,410 | tourism | Grande-Terre | |

| 4 | Petit-Bourg | 22,171 | 20,528 | agriculture | Basse-Terre | |

| 5 | Le Moule | 21,347 | 20,827 | agriculture | Grande-Terre | |

Health

In 2011, life expectancy at birth was recorded at 77.0 years for males and 83.5 for females.[46]

Medical centers in Guadeloupe include: University Hospital Center (CHU) in Pointe-à-Pitre, Regional Hospital Center (CHR) in Basse-Terre, and four hospitals located in Capesterre-Belle-Eau, Pointe-Noire, Bouillante and Saint-Claude.

The Institut Pasteur de la Guadeloupe, is located in Pointe-à-Pitre and is responsible for researching environmental hygiene, vaccinations, and the spread of tuberculosis and mycobacteria[47]

Governance

Together with Martinique, La Réunion, Mayotte and French Guiana, Guadeloupe is one of the overseas departments, being both a region and a department combined into one entity.[2] It is also an outermost region of the European Union. The inhabitants of are French citizens with full political and legal rights.

Legislative powers are centred on the separate departmental and regional councils.[2] The elected president of the Departmental Council of Guadeloupe is currently Josette Borel-Lincertin; its main areas of responsibility include the management of a number of social and welfare allowances, of junior high school (collège) buildings and technical staff, and local roads and school and rural buses. The Regional Council of Guadeloupe is a body, elected every six years, consisting of a president (currently Ary Chalus) and eight vice-presidents. The regional council oversees secondary education, regional transportation, economic development, the environment, and some infrastructure, among other things.

Guadeloupe elects one deputy from one of each of the first, second, third, and fourth constituencies to the National Assembly of France. Three senators are chosen for the Senate of France by indirect election.[2] For electoral purposes, Guadeloupe is divided into two arrondissements (Basse-Terre and Pointe-à-Pitre), and 21 cantons.

Most of the French political parties are active in Guadeloupe. In addition there are also regional parties such as the Guadeloupe Communist Party, the Progressive Democratic Party of Guadeloupe, the Guadeloupean Objective, the Pluralist Left, and United Guadaloupe, Socialism and Realities.

The prefecture (regional capital) of Guadeloupe is Basse-Terre. Local services of the state administration are traditionally organised at departmental level, where the prefect represents the government.[2]

For the purposes of local government, Guadeloupe is divided into 32 communes.[2] Each commune has a municipal council and a mayor. Revenues for the communes come from transfers from the French government, and local taxes. Administrative responsibilities at this level include water management, acts of birth, marriage, etc., and municipal police.

Symbols and flags

As a part of France, Guadeloupe uses the French tricolour as its flag and La Marseillaise as its anthem.[48] However, a variety of other flags are also used in an unofficial or informal context, most notably the sun-based flag. Independentists also have their own flag.

National flag of France

National flag of France.svg.png) Colonial flag of Guadeloupe

Colonial flag of Guadeloupe_variant.svg.png) Red variant of the colonial sun flag

Red variant of the colonial sun flag.svg.png) Flag used by the independence and the cultural movements

Flag used by the independence and the cultural movements Logo of the Regional Council of Guadeloupe

Logo of the Regional Council of Guadeloupe

Economy

The economy of Guadeloupe depends on tourism, agriculture, light industry and services.[49] It is reliant upon mainland France for large subsidies and imports and public administration is the largest single employer on the islands.[2][50] Unemployment is especially high among the youth population.[51]

In 2006, the GDP per capita of Guadeloupe at market exchange rates, not at PPP, was €17,338 (US$21,780).[52]

GDP: real exchange rate - US$9.74 billion (in 2006)[53]

GDP - real growth rate: NA%

GDP - per capita: real exchange rate - US$21,780 (in 2006)[54]

Exports: US$676 million (in 2005)[55]

Exports - commodities: bananas, sugar, rum

Imports: US$3.102 billion (in 2005)[55]

Tourism

Tourism is the one of the most prominent sources of income, with most visitors coming from France and North America.[56] An increasingly large number of cruise ships visit Guadeloupe, the cruise terminal of which is in Pointe-à-Pitre.[57]

Agriculture

The traditional sugar cane crop is slowly being replaced by other crops, such as bananas (which now supply about 50% of export earnings), eggplant, guinnep, noni, sapotilla, giraumon squash, yam, gourd, plantain, christophine, cocoa, jackfruit, pomegranate, and many varieties of flowers.[2] Other vegetables and root crops are cultivated for local consumption, although Guadeloupe is dependent upon imported food, mainly from the rest of France.

Culture

Language

Guadeloupe's official language is French, which is spoken by nearly all of the population.[2][58] In addition, most of the population can also speak Guadeloupean Creole, a variety of Antillean Creole. Traditionally stigmatised as the language of the Creole majority, attitudes have changed in recent decades. In the early 1970s to the mid 1980s Guadeloupe saw the rise and fall of an at-times violent movement for (greater) political independence from France,[59][60] and Creole was claimed as key to local cultural pride and unity. In the 1990s, in the wake of the independence movement's demise, Creole retained its de-stigmatized status as a symbol of local culture, albeit without de jure support from the state and without being practiced with equal competence in all strata and age groups of society.[61][62] However, the language has since gained greater acceptance on the part of France, such that it was introduced as an elective in public schools. Today, the question as to whether French and Creole are stable in Guadeloupe, i.e. whether both languages are practised widely and competently throughout society, remains a subject of active research.[63]

Religion

About 80% of the population are Roman Catholic.[2] Guadeloupe is in the diocese of Basse-Terre (et Pointe-à-Pitre).[64][65] Other major religions include various Protestant denominations.[2]

Literature

Guadeloupe has always had a rich literary output, with Guadeloupean author Saint-John Perse winning the 1960 Nobel Prize in Literature. Other prominent writers from Guadeloupe or of Guadeloupean descent include Maryse Condé, Simone Schwarz-Bart, Myriam Warner-Vieyra, Oruno Lara, Daniel Maximin, Paul Niger, Guy Tirolien and Nicolas-Germain Léonard.

Music

Music and dance are also very popular, and the interaction of African, French and Indian cultures[66] has given birth to some original new forms specific to the archipelago, most notably zouk music.[67] Since the 1970s, Guadeloupean music has increasingly claimed the local language, Guadeloupean Creole as the preferred language of popular music. Islanders enjoy many local dance styles including zouk, zouk-love, compas, as well as the modern international genres such as hip hop, etc.

Traditional Guadeloupean music includes biguine, kadans, cadence-lypso, and gwo ka. Popular music artists and bands such as Experience 7, Francky Vincent, Kassav' (which included Patrick St-Eloi, and Gilles Floro) embody the more traditional music styles of the island, whilst other musical artists such as the punk band The Bolokos (1) or Tom Frager focus on more international genres such as rock or reggae. Many international festivals take place in Guadeloupe, such as the Creole Blues Festival on Marie-Galante. All the Euro-French forms of art are also ubiquitous, enriched by other communities from Brazil, Dominican Republic, Haiti, India, Lebanon, Syria) who have migrated to the islands.

Classical music has seen a resurgent interest in Guadeloupe. One of the first known composers of African origin was born in Guadeloupe, Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges, a contemporary of Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and a celebrated figure in Guadeloupe. Several monuments and cites are dedicated to Saint-Georges in Guadeloupe, and there is an annual music festival, Festival International de Musique Saint-Georges, dedicated in his honour.[68] The festival attracts classical musicians from all over the world and is one of the largest classical music festivals in the Caribbean.[69]

Another element of Guadeloupean culture is its dress. A few women (particularly of the older generation) wear a unique style of traditional dress, with many layers of colourful fabric, now only worn on special occasions. On festive occasions they also wore a madras (originally a "kerchief" from South India) headscarf tied in many different symbolic ways, each with a different name. The headdress could be tied in the "bat" style, or the "firefighter" style, as well as the "Guadeloupean woman". Jewellery, mainly gold, is also important in the Guadeloupean lady's dress, a product of European, African and Indian inspiration.

Sport

Football (soccer) is popular in Guadeloupe, and several notable footballers are of Guadeloupean origin, including Marius Trésor, Stéphane Auvray, Ronald Zubar and his younger brother Stéphane, Miguel Comminges, Dimitri Foulquier, Bernard Lambourde, Anthony Martial, Alexandre Lacazette, Thierry Henry, Lilian Thuram, William Gallas, Layvin Kurzawa Thomas Lemar and Kingsley Coman.

The national football team were 2007 CONCACAF Gold Cup semi-finalists, defeated by Mexico.

Basketball is also popular. Best known players are the NBA players Rudy Gobert, Mickaël Piétrus, Johan Petro, Rodrigue Beaubois, and Mickael Gelabale (now playing in Russia), who were born on the island.

Several track and field athletes, such as Marie-José Pérec, Patricia Girard-Léno, Christine Arron, and Wilhem Belocian, are also Guadeloupe natives. Triple Olympic champion Marie-José Pérec, and fourth-fastest 100-metre (330-foot) runner Christine Arron.

The island has produced many world-class fencers. Yannick Borel, Daniel Jérent, Ysaora Thibus, Anita Blaze, Enzo Lefort and Laura Flessel were all born and raised in Guadeloupe. According to olympic gold medalist and world champion Yannick Borel, there is a good fencing school and a culture of fencing in Guadeloupe.[70]

Even though Guadeloupe is part of France, it has its own sports teams. Rugby union is a small but rapidly growing sport in Guadeloupe.

The island is also internationally known for hosting the Karujet Race – Jet Ski World Championship since 1998. This nine-stage, four-day event attracts competitors from around the world (mostly Caribbeans, Americans, and Europeans). The Karujet, generally made up of seven races around the island, has an established reputation as one of the most difficult championships in which to compete.

The Route du Rhum is one of the most prominent nautical French sporting events, occurring every four years.

Bodybuilder Serge Nubret was born in Anse-Bertrand, Grande-Terre, representing the French state in various bodybuilding competitions throughout the 1960s and 1970s including the IFBB's Mr. Olympia contest, taking 3rd place every year from 1972 to 1974, and 2nd place in 1975.[71] Bodybuilder Marie-Laure Mahabir also hails from Guadeloupe.

The country has also a passion for cycling. It hosted the French Cycling Championships in 2009 and continues to host the Tour de Guadeloupe every year.

Guadeloupe also continues to host the Orange Open de Guadeloupe tennis tournament (since 2011).

The Tour of Guadeloupe sailing, which was founded in 1981.

In boxing, the following athletes come from the island of Guadeloupe: Ludovic Proto (amateur; competed in the 1988 Summer Olympics in the men's light welterweight division), Gilbert Delé (professional; held the European light-middleweight title from 1989 to 1990, then won the WBA light-middleweight title in 1991, by defeating Carlos Elliott via TKO), and Jean-Marc Mormeck (professional; former two-time unified cruiserweight champion—held the WBA, WBC, and The Ring world titles twice between 2005 and 2007).

Transport

Guadeloupe is served by a number of airports; most international flights use Pointe-à-Pitre International Airport.[2] Boats and cruise ships frequent the islands, using the ports at Pointe-à-Pitre and Basse-Terre.[2]

On 9 September 2013 the county government voted in favour of constructing a tramway in Pointe-à-Pitre. The first phase will link northern Abymes to downtown Pointe-à-Pitre by 2019. The second phase, scheduled for completion in 2023, will extend the line to serve the university.[72]

Crime

Guadeloupe is one of the safest islands in the Caribbean;[73] nevertheless, it was the most violent overseas French department in 2016.[74] The murder rate is slightly more than that of Paris, at 8.2 per 100,000. The high level of unemployment caused violence and crime to rise especially in 2009 and 2010, the years following a great worldwide recession.[75] While the residents of Guadeloupe describe the island as a place with little everyday crime, most violence is caused by the drug trade or domestic disputes.[73]

See also

- Bibliography of Guadeloupe

- Index of Guadeloupe-related articles

- List of colonial and departmental heads of Guadeloupe

- Overseas departments and territories of France

- Slavery in the British and French Caribbean

References

- "Panorama - Guadeloupe". Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques. Gouvernment de France. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Encyclopedia Britannica - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "CIA World Factbook (2006) - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "CIA World Factbook (2006) - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Guadeloupe: These tiny islands are the French Caribban's greatest secret". CNN. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Gaudeloupe, a land of history". Region Guadeloupe. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Siegel et al - Analyse préliminaire de prélèvements sédimentaires en provenance de Marie-Galante. Bilan scientifique 2006-2008. Service régional de l’archéologie Guadeloupe- Saint-Martin – Saint-Barthélemy 2009.

- "Paleoenvironmental evidence for first human colonization of the eastern Caribbean". 2015. pp. 275–295. ISSN 0277-3791..

- "Guadeloupe from precolumbian times until today". Antilles Info Tourisme. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Guadeloupe History Timeline". World Atlas. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- La Guadeloupe: renseignements sur l'histoire, la flore, la faune, la géologie, la minéralogie, l'agriculture, le commerce, l'industrie, la législation, l'administration, Volume 1, Partie 2, de Jules Ballet (Imprimerie du gouvernement, 1895) (in French)

- "History of Guadeloupe". caribya!. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Guadeloupe > History". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Treaty of Paris, 1763". Office of the Historian. United States Government. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Auguste Lacour, Histoire de la Guadeloupe, vol. 1 (1635-1789). Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe, 1855 full text at Google Books, p. 236ff.

- Moitt, Bernard (1996). David Barry Gaspar (ed.). "Slave women and Resistance in the French Caribbean". More than Chattel: Black Women and Slavery in the Americas. Indiana University Press: 243. ISBN 0-253-33017-3.

- "Memorial in homage to Delgrès - Basse Terre - Cartographie des Mémoires de l'Esclavage". www.mmoe.llc.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Lindqvist, Herman (2015). Våra kolonier : de vi hade och de som aldrig blev av. Albert Bonniers Förlag. p. 232. ISBN 9789100155346.

- A remote French Island reconnects with India – Top News Law

- Chambre de commerce et d'industrie de la Guyane. "DOSSIER DE PRESSE" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015..

- "14 février 1952: une grève en Guadeloupe réprimée dans le sang, France24.com, 14 février 2009".

- Le petit lexique colonial

- "Source : Le Nouvel Observateur".

- "Mai 1967 à Pointe-à-Pitre : « Un massacre d'Etat »" (in French). 25 May 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- Félix-Hilaire Fortuné (2001). La France et l'Outre-Mer antillais [France and the West Indies] (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 303.

- Article du Monde En Guadeloupe, la tragédie de "Mé 67" refoulée, Béatrice Gurrey

- "Race, class fuel social conflict on French Caribbean islands". Agence France-Presse (AFP). 17 February 2009

- Shirbon, Estelle (13 February 2009). "Paris fails to end island protests, seen spreading". Reuters. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- "France proposes to raise salaries to end Guadeloupe violence". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 19 February 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- Sarkozy offers autonomy vote for Martinique, AFP

- "Guadeloupe". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "CIA World Factbook (2006) - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "CIA World Factbook (2006) - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Geography and geology". Le Guide Guadeloupe. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- "Guadeloupe" (PDF). Institut de physique du globe de Paris. Universite de Paris. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- Samper, A.; Quidelleur, X.; Lahitte, P.; Mollex, D. (2007). "Timing of effusive volcanism and collapse events within an oceanic arc island: Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe archipelago (Lesser Antilles Arc)". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 258: 175–191. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2007.03.030.

- Bourdon, E; Bouchot, V; Gadalia, A; Sanjuan, B. "Geology and geothermal activity of the Bouillante Volcanic Chain" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "CIA World Factbook (2006) - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Barnes, Joe (19 September 2017). "Hurricane Maria DAMAGE update: First signs of devastation after storm batters Guadeloupe". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Fwd: Hurricane Maria in Guadeloupe". stormcarib.com. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Euan McKirdy; Holly Yan. "Hurricane Maria cripples Dominica as it churns toward Puerto Rico". CNN. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Climatological Information for Guadeloupe". Archived from the original on 3 April 2012.

- INSEE. "Recensement de la population en Guadeloupe - 402 119 habitants au 1er janvier 2013" (in French). Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Jackson, Regine (2011). Geographies of Haitian Diaspora. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 1136807888. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- INSEE. "Recensement de la population en Guadeloupe - 402 119 habitants au 1er janvier 2013" (in French). Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "Population". Insee.

- Rastogi, Nalin. "Institut Pasteur de la Guadeloupe". Institut Pasteur de la Guadeloupe. Rastogi, Nalin. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "Constitution du 4 octobre 1958" [Constitution of 4 October 1958]. www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- "CIA World Factbook (2006) - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "CIA World Factbook (2006) - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "CIA World Ffactbook (2006) - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- INSEE-CEROM. "Tableau de bord économique de la Guyane" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- (in French) INSEE-CEROM. "Les comptes économiques de la Guadeloupe en 2006" (PDF). Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- (in French) INSEE-CEROM. "Tableau de bord économique de la Guyane" (PDF). Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- (in French) INSEE-CEROM. "Les comptes économiques de la Guadeloupe en 2006" (PDF). Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- "CIA World Factbook (2006) - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Guadeloupe Cruise Port". cruisecritic. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "CIA World Factbook (2006) - Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Schnepel, Ellen. In Search of a National Identity: Creole and Politics in Guadaloupe. University of Wisconsin Press (7 July 2004)

- Bebel-Gisler, D. (1976). La langue créole, force jugulée: Etude sociolinguistique desrapports de force entre le créole et le français aux Antilles (The creole language, represssed power: Sociolinguistic study of the power relations between Creole andFrench in the Antilles). Paris: Harmattan.

- Meyjes, Gregory Paul P, On the status of Creole in Guadeloupe: a study of present-day language attitudes. Unpub. PhD. Dissertation. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 1995.

- Durizot-Jno-Baptiste, Paulette. La question du créole à l'école en Guadeloupe : quelle dynamique? Paris, France : L'Harmattan, 1996.

- Manahan, Kathe. Diglossia Reconsidered: Language Choice and Code-Switching in Guadeloupean Voluntary Organizations, Kathe Manahan Texas Linguistic Forum. 47: 251-261, Austin, TX. 2004

- "Diocese of Basse-Terre (et Pointe-à-Pitre)". Catholic Hierarchy. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Neuvaine à l'Immaculée Conception (30 novembre au 8 décembre) 2016". Diocese Guadeloupe. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Sahai, Sharad (1998). Guadeloupe Lights Up: French-lettered Indians in a remote corner of the Caribbean reclaim their Hindu identity Archived 1 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Hinduism Today, Digital Edition, February 1998.

- Pareles, Jon (1988). "Zouk, a Distinctive, Infectious Dance Music". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "Site officiel de l'association du Festival international de musique Saint-Georges". saintgeorgesfestival.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "The Saint-Georges International Music Festival, Guadeloupe, French West Indies by Mark Laiosa". arttimesjournal.com. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Scarnecchia, Arianna. "Yannick Borel: "I hope the Worlds will be a big challenge"". Pianeta Scherma International. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- "Mr. Olympia Contest Results". www.getbig.com.

- Dinane, Nathalie; Blumstein, Emmanuel (10 September 2013). "Tramway, un projet sur les rails pour 2019". France-Antilles (in French). Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Graff, Vincent. (2013), "Death in Paradise: Ben Miller on investigating the deadliest place on the planet," Radio Times, 8 January 2013

- Guadeloupe : la spirale de la violence, francetvinfo.fr, 29 September 2016

- Borredon, Laurent. (2011), "Crime and Unemployment Dog Guadeloupe," The Guardian, 27 December 2011

External links

| The Wikibook Geography of France has a page on the topic of: Guadeloupe |