Deutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank AG (German pronunciation: [ˈdɔʏ̯tʃə ˈbaŋk ʔaːˈɡeː] (![]()

| |

Deutsche Bank Twin Towers in Frankfurt, Germany | |

| Aktiengesellschaft | |

| Traded as | |

| ISIN | DE0005140008 |

| Industry | |

| Founded | 10 March 1870 |

| Founder | Ludwig Bamberger |

| Headquarters | Deutsche Bank Twin Towers Frankfurt, Germany |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | |

| Services | Private banking |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 86,824 (Q2 2020)[3] |

| Website | db |

The bank's network spans 58 countries with a large presence in Europe, the Americas and Asia.[4] As of 2017–2018, Deutsche Bank was the 17th largest bank in the world by total assets.[5] As the largest German banking institution, it is a component of the DAX stock market index.

The company is a universal bank with three major divisions: the Private & Commercial Bank, the Corporate & Investment Bank (CIB), and Asset Management (DWS). Its investment banking operations often command substantial deal flow.

History

1870–1919

Deutsche Bank was founded in Berlin in 1870 as a specialist bank for financing foreign trade and promoting German exports.[6][7] It subsequently played a large part in developing Germany's industry, as its business model focused on providing finance to industrial customers.[7] The bank's statute was adopted on 22 January 1870, and on 10 March 1870 the Prussian government granted it a banking licence. The statute laid great stress on foreign business:

The object of the company is to transact banking business of all kinds, in particular, to promote and facilitate trade relations between Germany, other European countries and overseas markets.[8]

Three of the founders were Georg Siemens, whose father's cousin had founded Siemens and Halske; Adelbert Delbrück and Ludwig Bamberger.[9] Prior to the founding of Deutsche Bank, German importers and exporters were dependent upon British and French banking institutions in the world markets—a serious handicap in that German bills were almost unknown in international commerce, generally disliked and subject to a higher rate of a discount than English or French bills.[10]

Founding members

- Hermann Zwicker (Bankhaus Gebr. Schickler, Berlin)

- Anton Adelssen (Bankhaus Adelssen & Co., Berlin)

- Adelbert Delbrück (Bankhaus Delbrück, Leo & Co.)

- Heinrich von Hardt (Hardt & Co., Berlin, New York)

- Ludwig Bamberger (politician, former chairman of Bischoffsheim, Goldschmidt & Co)

- Victor Freiherr von Magnus (Bankhaus F. Mart Magnus)

- Adolph vom Rath (Bankhaus Deichmann & Co., Cologne)

- Gustav Kutter (Bankhaus Gebrüder Sulzbach, Frankfurt)

- Gustav Müller (Württembergische Vereinsbank, Stuttgart)

First directors

- Wilhelm Platenius, Georg Siemens and Hermann Wallich

The bank's first domestic branches, inaugurated in 1871 and 1872, were opened in Bremen[11] and Hamburg.[12] Its first oversea-offices opened in Shanghai in 1872[13] and London in 1873[14] followed by South American offices between 1874 and 1886.[9] The branch opening in London, after one failure and another partially successful attempt, was a prime necessity for the establishment of credit for the German trade in what was then the world's money centre.[10]

Major projects in the early years of the bank included the Northern Pacific Railroad in the US[15] and the Baghdad Railway[16] (1888). In Germany, the bank was instrumental in the financing of bond offerings of steel company Krupp (1879) and introduced the chemical company Bayer to the Berlin stock market.

The second half of the 1890s saw the beginning of a new period of expansion at Deutsche Bank. The bank formed alliances with large regional banks, giving itself an entrée into Germany's main industrial regions. Joint ventures were symptomatic of the concentration then under way in the German banking industry. For Deutsche Bank, domestic branches of its own were still something of a rarity at the time; the Frankfurt branch[17] dated from 1886 and the Munich branch from 1892, while further branches were established in Dresden and Leipzig[18] in 1901.

In addition, the bank rapidly perceived the value of specialist institutions for the promotion of foreign business. Gentle pressure from the Foreign Ministry played a part in the establishment of Deutsche Ueberseeische Bank[19] in 1886 and the stake taken in the newly established Deutsch-Asiatische Bank[20] three years later, but the success of those companies showed that their existence made sound commercial sense.

1919–1933

In 1919, the bank purchased the state's share of Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft (Ufa).[21] In 1926, the bank assisted in the merger of Daimler and Benz.[21][22]

The bank merged with other local banks in 1929 to create Deutsche Bank und DiscontoGesellschaft.[23] In 1937, the company name changed back to Deutsche Bank.[24]

1933–1945

After Adolf Hitler came to power, instituting the Third Reich, Deutsche Bank dismissed its three Jewish board members in 1933. In subsequent years, Deutsche Bank took part in the aryanization of Jewish-owned businesses; according to its own historians, the bank was involved in 363 such confiscations by November 1938.[25] During the war, Deutsche Bank incorporated other banks that fell into German hands during the occupation of Eastern Europe. Deutsche Bank provided banking facilities for the Gestapo and loaned the funds used to build the Auschwitz camp and the nearby IG Farben facilities.[26]

During World War II, Deutsche Bank became responsible for managing the Bohemian Union Bank in Prague, with branches in the Protectorate and in Slovakia, the Bankverein in Yugoslavia (which has now been divided into two financial corporations, one in Serbia and one in Croatia), the Albert de Barry Bank in Amsterdam, the National Bank of Greece in Athens, the Creditanstalt-Bankverein in Austria and Hungary, the Deutsch-Bulgarische Kreditbank in Bulgaria, and Banca Comercială Română (The Romanian Commercial Bank) in Bucharest. It also maintained a branch in Istanbul, Turkey.

In 1999, Deutsche Bank confirmed officially that it had been involved in Auschwitz.[26] In December 1999 Deutsche, along with other major German companies, contributed to a US$5.2 billion compensation fund following lawsuits brought by Holocaust survivors.[27][28] The history of Deutsche Bank during the Second World War has since been documented by independent historians commissioned by the Bank.[25]

Post-WWII

Following Germany's defeat in World War II, the Allied authorities, in 1948, ordered Deutsche Bank's break-up into ten regional banks. These 10 regional banks were later consolidated into three major banks in 1952: Norddeutsche Bank AG; Süddeutsche Bank AG; and Rheinisch-Westfälische Bank AG. In 1957, these three banks merged to form Deutsche Bank AG with its headquarters in Frankfurt.

In 1959, the bank entered retail banking by introducing small personal loans. In the 1970s, the bank pushed ahead with international expansion, opening new offices in new locations, such as Milan (1977), Moscow, London, Paris, and Tokyo. In the 1980s, this continued when the bank paid U$603 million in 1986 to acquire Banca d'America e d'Italia.[29]

In 1989, the first steps towards creating a significant investment-banking presence were taken with the acquisition of Morgan, Grenfell & Co., a UK-based investment bank. By the mid-1990s, the buildup of a capital-markets operation had got underway with the arrival of a number of high-profile figures from major competitors. Ten years after the acquisition of Morgan Grenfell, the US firm Bankers Trust was added. Bankers Trust suffered major losses in the summer of 1998 due to the bank having a large position in Russian government bonds,[30] but avoided financial collapse by being acquired by Deutsche Bank for $10 billion in November 1998.[31] This made Deutsche Bank the fourth-largest money management firm in the world after UBS, Fidelity Investments, and the Japanese post office's life insurance fund.[31] At the time, Deutsche Bank owned a 12% stake in DaimlerChrysler but United States banking laws prohibit banks from owning industrial companies, so Deutsche Bank received an exception to this prohibition through 1978 legislation from Congress.[31]

Deutsche continued to build up its presence in Italy with the acquisition in 1993 of Banca Popolare di Lecco from Banca Popolare di Novara for about $476 million.[32] In 1999, it acquired a minority interest in Cassa di Risparmio di Asti.

The Deutsche Bank Building in Lower Manhattan, formerly Bankers Trust Plaza, was heavily damaged by the collapse of the South Tower of the World Trade Center in the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.[33] Demolition work on the 39-story building continued for nearly a decade, and was completed in early 2011.[34]

In October 2001, Deutsche Bank was listed on the New York Stock Exchange. This was the first NYSE listing after interruption due to 11 September attacks. The following year, Josef Ackermann became CEO of Deutsche Bank and served as CEO until 2012 when he became involved with the Bank of Cyprus.[35][36] Then, beginning in 2002, Deutsche Bank strengthened its U.S. presence when it purchased Scudder Investments.[37] Meanwhile, in Europe, Deutsche Bank increased its private-banking business by acquiring Rued Blass & Cie (2002) and the Russian investment bank United Financial Group (2005) founded by the United States banker Charles Ryan and the Russian official Boris Fyodorov which followed Anshu Jain's aggressive expansion to gain strong relationships with state partners in Russia.[38][39] Jain persuaded Ryan to remain with Deutsche Bank at its new Russian offices and later, in April 2007, sent the President and Chairman of the Management Board of VTB Bank Andrey Kostin's son Andrey to Deutsche Bank's Moscow office.[38][40][lower-alpha 1] Later, in 2008, to establish VTB Capital, numerous bankers from Deutsche Bank's Moscow office were hired by VTB Capital.[36][42][43] In Germany, further acquisitions of Norisbank, Berliner Bank and Deutsche Postbank strengthened Deutsche Bank's retail offering in its home market. This series of acquisitions was closely aligned with the bank's strategy of bolt-on acquisitions in preference to so-called "transformational" mergers. These formed part of an overall growth strategy that also targeted a sustainable 25% return on equity, something the bank achieved in 2005.

When Citibank, Manufacturers Hanover, Chemical, Bankers Trust, and 68 other entities refused to financially support Donald Trump in the early 1990s, Donald Trump heavily relied upon Deutsche Bank for financial backing from its commercial real estate division since the mid-1990s.[38][39][44][lower-alpha 2] A few years after Trump sued Deutsche Bank for $3 billion in 2008, Trump shifted his financial portfolio from the investment banking division to the private wealth division with Rosemary Vrablic, formerly of Citigroup, Bank of America, and Merrill Lynch, becoming Trump's new and as of 2017 current personal banker at Deutsche Bank.[36][47][48]

The company's headquarters, the Deutsche Bank Twin Towers building, was extensively renovated beginning in 2007. The renovation took approximately three years to complete. The renovated building was certified LEED Platinum and DGNB Gold.

The bank developed, owned, and operated the Cosmopolitan of Las Vegas, after the project's original developer defaulted on its borrowings. Deutsche Bank opened the casino in 2010 and ran it at a loss until its sale in May 2014. The bank's exposure at the time of sale was more than $4 billion, however it sold the property to Blackstone Group for $1.73 billion.[49]

Financial crisis years (2007–2012)

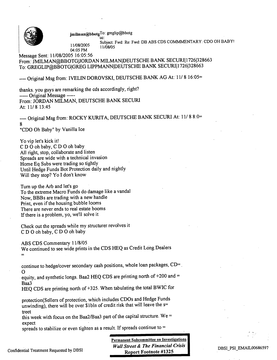

Housing credit bubble and CDO market

Deutsche Bank was one of the major drivers of the collateralized debt obligation (CDO) market during the housing credit bubble from 2004 to 2008, creating about $32 billion worth. The 2011 US Senate Permanent Select Committee on Investigations report on Wall Street and the Financial Crisis analyzed Deutsche Bank as a case study of investment banking involvement in the mortgage bubble, CDO market, credit crunch, and recession. It concluded that even as the market was collapsing in 2007, and its top global CDO trader was deriding the CDO market and betting against some of the mortgage bonds in its CDOs, Deutsche bank continued to churn out bad CDO products to investors.[50]

The report focused on one CDO, Gemstone VII, made largely of mortgages from Long Beach, Fremont, and New Century, all notorious subprime lenders. Deutsche Bank put risky assets into the CDO, like ACE 2006-HE1 M10, which its own traders thought was a bad bond. It also put in some mortgage bonds that its own mortgage department had created but could not sell, from the DBALT 2006 series. The CDO was then aggressively marketed as a good product, with most of it being described as having A level ratings. By 2009 the entire CDO was almost worthless and the investors (including Deutsche Bank itself) had lost most of their money.[50]

Greg Lippmann, head of global CDO trading, was betting against the CDO market, with approval of management, even as Deutsche was continuing to churn out product. He was a large character in Michael Lewis' book The Big Short, which detailed his efforts to find 'shorts' to buy Credit Default Swaps for the construction of Synthetic CDOs. He was one of the first traders to foresee the bubble in the CDO market as well as the tremendous potential that CDS offered in this. As portrayed in The Big Short, Lipmann in the middle of the CDO and MBS frenzy was orchestrating presentations to investors, demonstrating his bearish view of the market, offering them the idea to start buying CDS, especially to AIG in order to profit from the forthcoming collapse. As regards the Gemstone VII deal, even as Deutsche was creating and selling it to investors, Lippman emailed colleagues that it 'blew', and he called parts of it 'crap' and 'pigs' and advised some of his clients to bet against the mortgage securities it was made of. Lippman called the CDO market a 'ponzi scheme', but also tried to conceal some of his views from certain other parties because the bank was trying to sell the products he was calling 'crap'. Lippman's group made money off of these bets, even as Deutsche overall lost money on the CDO market.[50]

Deutsche was also involved with Magnetar Capital in creating its first Orion CDO. Deutsche had its own group of bad CDOs called START. It worked with Elliot Advisers on one of them; Elliot bet against the CDO even as Deutsche sold parts of the CDO to investors as good investments. Deutsche also worked with John Paulson, of the Goldman Sachs Abacus CDO controversy, to create some START CDOs. Deutsche lost money on START, as it did on Gemstone.[50]

On 3 January 2014, it was reported that Deutsche Bank would settle a lawsuit brought by US shareholders, who had accused the bank of bundling and selling bad real estate loans before the 2008 downturn. This settlement came subsequent and in addition to Deutsche's $1.93 billion settlement with the US Housing Finance Agency over similar litigation related to the sale of mortgage-backed securities to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.[51]

Leveraged super-senior trades

Former employees including Eric Ben-Artzi and Matthew Simpson have claimed that during the crisis Deutsche failed to recognise up to $12bn of paper losses on their $130bn portfolio of leveraged super senior trades, although the bank rejects the claims.[52] A company document of May 2009 described the trades as "the largest risk in the trading book",[53] and the whistleblowers allege that had the bank accounted properly for its positions its capital would have fallen to the extent that it might have needed a government bailout.[52] One of them claims that "If Lehman Brothers didn't have to mark its books for six months it might still be in business, and if Deutsche had marked its books it might have been in the same position as Lehman."[53]

Deutsche had become the biggest operator in this market, which were a form of credit derivative designed to behave like the most senior tranche of a CDO.[53] Deutsche bought insurance against default by blue-chip companies from investors, mostly Canadian pension funds, who received a stream of insurance premiums as income in return for posting a small amount of collateral.[53] The bank then sold protection to US investors via the CDX credit index, the spread between the two was tiny but was worth $270m over the 7 years of the trade.[53] It was considered very unlikely that many blue chips would have problems at the same time, so Deutsche required collateral of just 10% of the contract value.

The risk of Deutsche taking large losses if the collateral was wiped out in a crisis was called the gap option.[53] Ben-Artzi claims that after modelling came up with "economically unfeasible" results, Deutsche accounted for the gap option first with a simple 15% "haircut" on the trades (described as inadequate by another employee in 2006) and then in 2008 by a $1–2bn reserve for the credit correlation desk designed to cover all risks, not just the gap option.[53] In October 2008 they stopped modelling the gap option and just bought S&P put options to guard against further market disruption, but one of the whistleblowers has described this as an inappropriate hedge.[53] A model from Ben-Artzi's previous job at Goldman Sachs suggested that the gap option was worth about 8% of the value of the trades, worth $10.4bn. Simpson claims that traders were not simply understating the gap option but actively mismarking the value of their trades.[53]

European financial crisis

Deutsche Bank has negligible exposure to Greece. Spain and Italy however account for a tenth of its European private and corporate banking business. According to the bank's own statistics the credit risks in these countries are about €18 billion (Italy) and €12 billion (Spain).[54]

For the 2008 financial year, Deutsche Bank reported its first annual loss in five decades,[55] despite receiving billions of dollars from its insurance arrangements with AIG, including US$11.8 billion from funds provided by US taxpayers to bail out AIG.[56]

Based on a preliminary estimation from the European Banking Authority (EBA) in October 2011, Deutsche Bank AG needed to raise capital of about €1.2 billion (US$1.7 billion) as part of a required 9 percent core Tier 1 ratio after sovereign debt writedown starting in mid-2012.[57]

It needs to get its common equity tier-1 capital ratio up to 12.5% in 2018 to be marginally above the 12.25% required by regulators. As of September 2017 it stands at 11.9%.[58]

Since 2012

In January 2014, Deutsche Bank reported a €1.2 billion ($1.6 billion) pre-tax loss for the fourth quarter of 2013. This came after analysts had predicted a profit of nearly €600 million, according to FactSet estimates. Revenues slipped by 16% versus the prior year.[59]

Deutsche Bank's Capital Ratio Tier-1 (CET1) was reported in 2015 to be only 11.4%, lower than the 12% median CET1 ratio of Europe's 24 biggest publicly traded banks, so there would be no dividend for 2015 and 2016.[60] Furthermore, 15,000 jobs were to be cut.[61]

In June 2015, the then co-CEOs, Jürgen Fitschen and Anshu Jain, both offered their resignations[62] to the bank's supervisory board, which were accepted. Jain's resignation took effect in June 2015, but he provided consultancy to the bank until January 2016. Fitschen continued as joint CEO until May 2016. The appointment of John Cryan as joint CEO was announced, effective July 2016; he became sole CEO at the end of Fitschen's term.[63]

In January 2016, Deutsche Bank pre-announced a 2015 loss before income taxes of approximately €6.1 billion and a net loss of approximately €6.7 billion.[64] Following this announcement, a bank analyst at Citi declared: "We believe a capital increase now looks inevitable and see an equity shortfall of up to €7 billion, on the basis that Deutsche may be forced to book another €3 billion to €4 billion of litigation charges in 2016."[65]

Since May 2017, its biggest shareholder is Chinese conglomerate HNA Group, which owns 10% of its shares.[66]

In November 2018, the bank had their Frankfurt offices raided by police in connection with ongoing investigations around the Panama papers and money laundering. Deutsche Bank released a statement confirming it would "cooperate closely with prosecutors".[67]

AUTO1 FinTech is a joint venture of AUTO1 Group, Allianz and Deutsche Bank.

During the Annual General Meeting in May 2019, CEO Christian Sewing said he was expecting a "deluge of criticism" about the bank's performance and announced that he was ready to make "tough cutbacks"[68] after the failure of merger negotiations with Commerzbank AG and weak profitability. According to the New York Times, "its finances and strategy [are] in disarray and 95 percent of its market value [has been] erased".[69] News headlines in late June 2019 claimed that the bank would cut 20,000 jobs, over 20% of its staff, in a restructuring plan.[70][71] On 8 July 2019, the bank began to cut 18,000 jobs, including entire teams of equity traders in Europe, the US, and Asia. On the previous day, Sewing had laid blame on unnamed predecessors who created a "culture of poor capital allocation" and chasing revenue for the sake of revenue, according to a Financial Times report, and promised that going forward, the bank "will only operate where we are competitive".[72][73]

It was reported in January 2020 that Deutsche Bank had decided to cut the bonus pool at its investment branch by 30% following restructuring efforts.[74]

Leadership history

When Deutsche Bank was first organized in 1870 there was no CEO. Instead the board was represented by a speaker of the board. Beginning in February 2012, the bank has been led by two co-CEOs; in July 2015 it announced it would be led by one CEO beginning in 2016.[75] The management bodies are the annual general meeting, supervisory board and management board.

| Begin | End | CEO/Speaker | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Christian Sewing | [76] | |

| 2015 | 2018 | John Cryan | co-CEO with Fitschen until 2016[77] |

| 2012 | 2016 | Jürgen Fitschen | co-CEO[77] |

| 2012 | 2015 | Anshu Jain | co-CEO with Fitschen[78] |

| 2002 | 2012 | Josef Ackermann | CEO position created 2006[79] |

| 1997 | 2002 | Rolf-Ernst Breuer | |

| 1989 | 1997 | Hilmar Kopper | |

| 1985 | 1989 | Alfred Herrhausen | assassinated |

| 1976 | 1988 | Friedrich Wilhelm Christians | |

| 1976 | 1985 | Wilfried Guth | |

| 1967 | 1976 | Franz Heinrich Ulrich | co-speaker[80] |

| 1967 | 1969 | Karl Klasen | co-speaker |

| 1957 | 1967 | Hermann Josef Abs |

Performance

| Year | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net income | €-5.2bn | €0.3bn | €-0.7bn | €-1.4bn | €-6.8bn | €1.7bn | €0.7bn | €0.3bn | €4.3bn | €2.3bn | €5.0bn | €−3.9bn | €6.5bn | €6.1bn | €3.5bn | €2.5bn | €1.4bn |

| Revenues | €23.2bn | €25.3bn | €30.0bn | €33.5bn | €31.9bn | €31.9bn | €33.7bn | €33.2bn | €28.6bn | €28.0bn | €13.5bn | €30.7bn | €28.5bn | €25.6bn | €21.9bn | €21.3bn | |

| Return on equity | 5.1% | 2.6% | – | – | 5% | 18% | −29% | 30% | 26% | 16% | 1% | 7% | |||||

| Dividend | – | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.0 | 0.75 | 0.75 | – | – | – | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

Corporate governance

| Name | Position |

|---|---|

| Dr. Paul Achleitner | Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Deutsche Bank AG |

| Detlef Polaschek | Deputy Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Deutsche Bank AG |

| Ludwig Blomeyer-Bartenstein | Spokesperson of the Management and Head of the Market Region Bremen |

| Frank Bsirske | |

| Mayree Caroll Clark | Founder and Managing Partner of Eachwin Capital |

| Jan Duscheck | Head of national working group Banking, trade union ver.di |

| Gerhard Eschelbeck | |

| Katherine Garrett-Cox | Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer, Gulf International Bank (UK) Ltd. |

| Timo Heider | Deputy Chairman of the Group Staff Council of Deutsche Bank AG |

| Martina Klee | Deputy Chairperson of the Staff Council PWCC Center Frankfurt of Deutsche Bank |

| Henriette Mark | Chairperson of the Combined Staff Council Southern Bavaria of Deutsche Bank |

| Gabriele Platscher | Chairperson of the Staff Council Niedersachsen Ost of Deutsche Bank |

| Bernd Rose | Member of the Group Staff Council and European Staff Council of Deutsche Bank |

| Gerd Alexander Schütz | Founder and Member of the Management Board, C-QUADRAT |

| Stephan Szukalski | Federal Chairman of the German Association of Bank Employees |

| John Aexander Thain | |

| Michelle Trogni | |

| Dr. Dagmar Valcarel | |

| Prof. Dr. Norbert Winkeljohann | Self-employed corporate consultant, Norbert Winkeljohann Advisory & Investments |

| Jürg Zeltner | Group CEO and Chairman of the Group Executive Committee,

Member of the Board of Directors, KBL European Private Bankers, Luxembourg |

| Name | Position |

|---|---|

| Christian Sewing | Chief Executive Officer |

| Frank Kuhnke | Chief Operating Officer |

| Werner Steinmüller | Chief Operating Officer Asia Pacific |

| Karl Von Rohr | Deputy Chairman (President) |

| Stuart Lewis | Chief Risk Officer |

| Fabrizio Campelli | Chief Transformation Officer |

| James Von Moltke | Chief Financial Officer |

Shareholders

Deutsche Bank is one of the leading listed companies in German post-war history. Its shares are traded on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange and, since 2001, also on the New York Stock Exchange and are included in various indices, including the DAX and the Euro Stoxx 50. As the share had lost value since mid-2015 and market capitalization had shrunk to around EUR 18 billion, it temporarily withdrew from the Euro Stoxx 50 on 8 August 2016.[81] With a 0.73% stake, it is currently the company with the lowest index weighting.[82]

In 2001, Deutsche Bank merged its mortgage banking business with that of Dresdner Bank and Commerzbank to form Eurohypo AG. In 2005, Deutsche Bank sold its stake in the joint company to Commerzbank.[83]

| Share | Shareholder | As of |

|---|---|---|

| 4.97 % | BlackRock | 2019 |

| 3.14 % | Douglas L. Braunstein (Hudson Executive Capital LP) | 2018 |

| 3.05 % | Paramount Services Holdings Ltd. | 2015 |

| 3.05 % | Supreme Universal Holdings Ltd. | 2015 |

| 3.001 % | Stephen A. Feinberg (Cerberus Capital Management) | 2017 |

| 0.19 % | C-QUADRAT Special Situations Dedicated Fund | 2019 |

Business divisions

The bank's business model rests on three pillars – the Corporate & Investment Bank (CIB), the Private & Commercial Bank and Asset Management (DWS).

Corporate & Investment Bank (CIB)

The Corporate & Investment Bank (CIB) is Deutsche Bank's capital markets business. The CIB comprises the below six units.[85]

- Corporate Finance is responsible for advisory and mergers & acquisitions (M&A).

- Equities / Fixed Income & Currencies. These two units are responsible for sales and trading of securities.

- Global Capital Markets (GCM) is focused on financing and risk management solutions. It includes debt and equity issuances.

- Global Transaction Banking (GTB) caters to corporates and financial institutions by providing commercial banking products including cross-border payments, cash management, securities services, and international trade finance.

- Deutsche Bank Research provides analysis of products, markets, and trading strategies.

Private & Commercial Bank

- Private & Commercial Clients Germany / International is the retail bank of Deutsche Bank. In Germany, it operates under two brands – Deutsche Bank and Postbank. Additionally, it has operations in Belgium, Italy, Spain and India. The businesses in Poland and Portugal are in the process of being sold.[86][87][88]

- Wealth Management functions as the bank's private banking arm, serving high-net-worth individuals and families worldwide. The division has a presence in the world's private banking hotspots, including Switzerland, Luxembourg, the Channel Islands, the Caymans and Dubai.[89]

Deutsche Asset Management (DWS)

Deutsche Bank holds a majority stake in the listed asset manager DWS Group (formerly Deutsche Asset Management), which was separated from the bank in March 2018.

Logotype

In 1972, the bank created the world-known blue logo "Slash in a Square" – designed by Anton Stankowski and intended to represent growth within a risk-controlled framework.[90]

Controversies

Deutsche Bank in general as well as specific employees have frequently figured in controversies and allegations of deceitful behavior or illegal transactions. As of 2016, the bank was involved in some 7,800 legal disputes and calculated €5.4 billion as litigation reserves,[91] with a further €2.2 billion held against other contingent liabilities.[65]

Tax evasion

Six former employees were accused of being involved in a major tax fraud deal with CO2 emission certificates, and most of them were subsequently convicted. It was estimated that the sum of money in the tax evasion scandal might have been as high as €850 million. Deutsche Bank itself was not convicted due to an absence of corporate liability laws in Germany.[92]

Espionage scandal

From as late as 2001 to at least 2007, the bank engaged in covert espionage on its critics. The bank has admitted to episodes of spying in 2001 and 2007 directed by its corporate security department, although characterizing them as "isolated".[93] According to the Wall Street Journal, Deutsche Bank had prepared a list of names of people who it wanted investigated for criticism of the bank, including Michael Bohndorf (an activist investor in the bank), Leo Kirch (a former media executive in litigation with the bank), and the Munich law firm of Bub Gauweiler & Partner, which represented Kirch.[93] According to the Wall Street Journal, the bank's legal department was involved in the scheme along with its corporate security department.[93] The bank has since hired Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, a New York law firm, to investigate the incidents on its behalf. The Cleary firm has concluded its investigation and submitted its report, which however has not been made public.[93] According to the Wall Street Journal, the Cleary firm uncovered a plan by which Deutsche Bank was to infiltrate the Bub Gauweiler firm by having a bank "mole" hired as an intern at the Bub Gauweiler firm. The plan was allegedly cancelled after the intern was hired but before she started work.[93] Peter Gauweiler, a principal at the targeted law firm, was quoted as saying "I expect the appropriate authorities including state prosecutors and the bank's oversight agencies will conduct a full investigation."[93]

In May 2009, Deutsche Bank informed the public that the executive management had learned about possible violations that occurred in past years of the bank's internal procedures or legal requirements in connection with activities involving the bank's corporate security department. Deutsche Bank immediately retained the law firm Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton in Frankfurt to conduct an independent investigation[94] and informed the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin). The principal findings by the law firm, published in July 2009,[95] found four incidents that raised legal issues, such as data protection or privacy concerns. In all incidents, the activities arose out of certain mandates performed by external service providers on behalf of the Bank's Corporate Security Department. The incidents were isolated, no systemic misbehaviour was found and there was no indication that present members of the Management Board had been involved in any activity that raises legal issues or has had any knowledge of such activities.[95] This was confirmed by the Public Prosecutor's Office in Frankfurt in October 2009.[96] BaFin found deficiencies in operations within Deutsche Bank's security unit in Germany but found no systemic misconduct by the bank.[97] The bank initiated steps to strengthen controls for the mandating of external service providers by its Corporate Security Department and their activities.[95]

Black Planet Award

In 2013, the CEOs Anshu Jain and Jürgen Fitschen as well as the major shareholders of Deutsche Bank were awarded the Black Planet Award of the Foundation Ethics & Economics (Ethecon Foundation).[98][99]

April 2015 Libor scandal

On 23 April 2015, Deutsche Bank agreed to a combined US$2.5 billion in fines – a US$2.175 billion fine by American regulators, and a €227 million penalty by British authorities – for its involvement in the Libor scandal uncovered in June 2012. It was one of several banks described as colluding to fix interest rates used to price hundreds of trillions of dollars of loans and contracts worldwide, including mortgages and student loans.[100][101] Deutsche Bank also pleaded guilty to wire fraud, acknowledging that at least 29 employees had engaged in illegal activity. It was required to dismiss all employees who were involved with the fraudulent transactions.[101] However, no individuals will be charged with criminal wrongdoing. In a Libor first, Deutsche Bank will be required to install an independent monitor.[100] Commenting on the fine, Britain's Financial Conduct Authority director Georgina Philippou said "This case stands out for the seriousness and duration of the breaches ... One division at Deutsche Bank had a culture of generating profits without proper regard to the integrity of the market. This wasn't limited to a few individuals but, on certain desks, it appeared deeply ingrained."[101] The fine represented a record for interest rate related cases, eclipsing a $1.5 billion Libor related fine to UBS, and the then-record $450 million fine assessed to Barclays earlier in the case.[101][100] The size of the fine reflected the breadth of wrongdoing at Deutsche Bank, the bank's poor oversight of traders, and its failure to take action when it uncovered signs of abuse internally.[100]

Role in 2007–08 financial crisis

In January 2017, Deutsche Bank agreed to a $7.2 billion settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice over its sale and pooling of toxic mortgage securities in the years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis. As part of the agreement, Deutsche Bank was required to pay a civil monetary penalty of $3.1 billion and provide $4.1 billion in consumer relief, such as loan forgiveness. At the time of the agreement, Deutsche Bank was still facing investigations into the alleged manipulation of foreign exchange rates, suspicious equities trades in Russia, as well as alleged violations of U.S. sanctions on Iran and other countries. Since 2012, Deutsche Bank had paid more than €12 billion for litigation, including a deal with U.S. mortgage-finance giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.[102]

2015 sanctions violations

On 5 November 2015, Deutsche Bank was ordered to pay US$258 million (€237.2 million) in penalties imposed by the New York State Department of Financial Services and the United States Federal Reserve Bank after the bank was caught doing business with Burma, Libya, Sudan, Iran, and Syria which were under US sanctions at the time. According to the US federal authorities, Deutsche Bank handled 27,200 US dollar clearing transactions valued at more than US$10.86 billion (€9.98 billion) to help evade US sanctions between early 1999 until 2006 which are done on behalf of Iranian, Libyan, Syrian, Burmese, and Sudanese financial institutions and other entities subject to US sanctions, including entities on the Specially Designated Nationals by the Office of Foreign Assets Control.[103][104]

In response to the penalties, the bank will pay US$200 million (€184 million) to the NYDFS while the rest (US$58 million; €53.3 million) will go to the Federal Reserve. In addition to the payment, the bank will install an independent monitor, fire six employees who were involved in the incident, and ban three other employees from any work involving the bank's US-based operations.[105] The bank is still under investigation by the US Justice Department and New York State Department of Financial Services into possible sanctions violations relating to the 2014–15 Ukrainian crisis and its activities within Russia.[106]

Dakota Access Pipeline

Environmentalists criticize Deutsche Bank for co-financing the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline, which is planned to run close to an Indian reservation and is seen as a threat to their livelihood by its inhabitants.[107][108]

Deutsche Bank has issued a statement addressing the criticism it received from various environmental groups.[109]

2017 money-laundering fine

In January 2017, the bank was fined $425 million by the New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS)[110] and £163 million by the UK Financial Conduct Authority[111] regarding accusations of laundering $10 billion out of Russia.[112][113][114]

Relationship with Donald Trump

Deutsche Bank is widely recognized as being the largest creditor to real-estate-mogul-turned-politician Donald Trump, 45th President of the United States, lending him and his company more than $2 billion over twenty years ending 2020.[115] The bank held more than $360 million in outstanding loans to the candidate in the months prior to his 2016 election. As of December 2017 Deutsche Bank's role in, and possible relevance to, Trump and Russian parties cooperating to elect him was reportedly under investigation by Special Counsel Robert Mueller.[116] As of March 2019, Deutsche Bank's relationship with Trump was reportedly also under investigation by two U.S. congressional committees and by the New York attorney general.[117][118][119]

In April 2019, House Democrats subpoenaed the Bank for Trump's personal and financial records.[120][121][122][123][124] On 29 April 2019, President Donald Trump, his business, and his children Donald Trump Jr., Eric Trump, and Ivanka Trump sued Deutsche Bank and Capital One bank to block them from turning over financial records to congressional committees that have issued subpoenas for the information.[125] On 22 May 2019, judge Edgardo Ramos of the federal District Court in Manhattan rejected the Trump suit against Deutsche Bank, ruling the bank must comply with congressional subpoenas.[126] Six days later, Ramos granted Trump's attorneys their request for a stay so they could pursue an expedited appeal through the courts.[127] In October 2019, a federal appeals court said the bank asserted it did not have Trump's tax returns.[128] In December 2019, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Deutsche Bank must release Trump's financial records, with some exceptions, to congressional committees; Trump was given seven days to seek another stay pending a possible appeal to the Supreme Court.[129]

The New York Times reported in May 2019 that anti-money laundering specialists in the bank detected what appeared to be suspicious transactions involving entities controlled by Trump and his son-in-law Jared Kushner, for which they recommended filing suspicious activity reports with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network of the Treasury Department, but bank executives rejected the recommendations. One specialist noted money moving from Kushner Companies to Russian individuals and flagged it in part because of the bank's previous involvement in a Russian money-laundering scheme.[130][131]

On 19 November 2019, Thomas Bowers, a former Deutsche Bank executive and head of American wealth management, was reported to have committed suicide in his Malibu home.[132] Bowers had been in charge of overseeing and personally signing over $360 million in high-risk loans for Trump's National Doral Miami resort.[133] The loans had been subject to a criminal investigation by special council Robert Mueller in his investigation of the president's 2016 campaign involvement in Russian election meddling. Documents on those loans have also been subpoenaed from Deutsche Bank by the House Democrats together with the financial documents of the president. A relationship between Bowers’s responsibilities and apparent suicide has not been established; the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner – Coroner has closed the case, giving no indication to wrongdoing by third parties.[134]

Relationship with Jeffrey Epstein

Deutsche Bank lent money and traded currencies for the well-known sex offender Jeffrey Epstein up to May 2019, long after Epstein's 2008 guilty plea in Florida to soliciting prostitution from underage girls, according to news reports.[135][136][137] Epstein and his businesses had dozens of accounts through the private-banking division.[138][139] According to The New York Times, Deutsche Bank managers overruled compliance officers who raised concerns about Epstein's reputation.[136]

The bank found suspicious transactions in which Epstein moved money out of the United States, the Times reported.[138]

The New York Department of Financial Services (DFS) imposed a $150 million penalty on Deutsche Bank on 7 July 2020, in connection with Epstein. The bank had "ignored red flags on Epstein".[140][141] From 2013 to 2018, "Epstein, his related entities and his associates" had opened over forty accounts with Deutsche Bank.[140]

Criminal cartel charges in Australia

On 1 June 2018, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) announced that criminal cartel charges were expected to be laid by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) against ANZ Bank, its group treasurer Rick Moscati, along with Deutsche Bank, Citigroup, and a number of individuals.[142][143]

Alleged involvement in Danske Bank money-laundering scandal

On 19 November 2018, a whistleblower on alleged money-laundering activities undertaken by Danske Bank stated that a large European bank was involved in helping Danske process $150 billion in suspect funds.[144] Although the whistleblower, Howard Wilkinson, did not name Deutsche Bank directly, another inside source claimed the institute in question was Deutsche Bank's U.S. unit.[145]

Improper handling of ADRs investigation

On 20 July 2018, Deutsche Bank agreed to pay nearly $75 million to settle charges of improper handling of "pre-released" American depositary receipts (ADRs) under investigation of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Deutsche Bank didn't admit or deny the investigation findings but agreed to pay disgorgement of more than $44.4 million in ill-gotten gains plus $6.6 million in prejudgment interest and a penalty of $22.2 million.[146][147]

Malaysian 1MDB fund

U.S. prosecutors are investigating Deutsche Bank's role in a multibillion-dollar fraud scandal involving the 1Malaysia Development Berhad, or 1MDB, according to news reports in July 2019.[148][149] Deutsche Bank helped raise $1.2 billion for the 1MDB in 2014.[149]

Acquisitions

- Mendelssohn & Co. 1938

- Morgan, Grenfell & Company, 1990

- Bankers Trust, 30 November 1998[150]

- Scudder Investments, 2001

- RREEF, 2002[151][152]

- Berkshire Mortgage Finance, 22 October 2004[153]

- Chapel Funding (now DB Home Lending), 12 September 2006[154]

- Norisbank, 2 November 2006

- MortgageIT, 3 January 2007[155]

- Hollandsche Bank-Unie, 2 July 2008

- Sal. Oppenheim, 2010

- Deutsche Postbank, 2010[156]

Notable employees

- Hermann Josef Abs, former chair (1957–1968)

- Paul Achleitner, Chairman of the Supervisory Board

- Josef Ackermann, former CEO (2002–2012)

- Michael Cohrs, former head of Global Banking (2002–2010)

- Sir John Craven – financier in London

- Jürgen Fitschen, former co-chair

- David Folkerts-Landau, head of Research

- Katherine Garrett-Cox, chief executive officer

- Alfred Herrhausen, former chair (1988–1989)

- Henry Jackson – founder of OpCapita

- Anshu Jain, former head of Corporate and Investment Banking

- Sajid Javid, (2007–2009)

- Otto Hermann Kahn – philanthropist

- Karl Kimmich, former chair (1942–1945)

- Georg von Siemens, co-founder and director (1870–1900)

- Johannes Teyssen, (chair of the management board of E.ON)

- Ted Virtue – executive board member

- Hermann Wallich, co-founder and director (1870–1893)

- Boaz Weinstein – derivatives trader

Notes

- Andrey Kostin (1979–2011), a Russian banker and son of Andrey Kostin who is the President and Chairman of the Management Board of VTB Bank, graduated from the Russian Government Finance Academy in 2000 and began working with Deutsche Bank's London office in 2000.[40] From 2002–2007, the younger Andrey Kostin worked in Deutsche Bank's Office of Interbank and Corporate Sales in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Africa.[40] In April 2007, Anshu Jain sent the younger Andrey Kostin to work at Deutsche Bank's Moscow office.[38][40] While he was at Deutsche Bank's Moscow office, the Moscow office began posting profits of $500 million to $1 billion a year.[38][40] He served on its management board beginning July 2008 and was the deputy chairman of the management board from February 2011.[40] On 2 July 2011, at 7:30 a.m., while he was at a vacation retreat reserved for FSB personnel, he died when his Can-Am Outlander-800 ATV crashed into a tree along a country road near Pereslavl-Zalessky and the village of Los (Russian: Лось) in the Yaroslavl region of Russia.[40] He was not wearing a helmet.[41]

- Justin Kennedy, son of Anthony Kennedy, and others such as Jon Vaccaro, Mike Offit, Steve Stuart, Eric Schwartz, and Tobin "Toby" Cobb are central to Donald Trump's financial support at Deutsche Bank.[44] Justin Kennedy worked for Deutsche Bank from 1997–2009 becoming the global head of real estate capital markets.[36][45][46]

References

- Ewing, Jack (8 April 2018). "Deutsche Bank Replaces C.E.O. Amid Losses and Lack of Direction". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Deutsche Bank Annual Report 2019" (PDF). db.com. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Interim Report as of June 30, 2020" (PDF).

- Deutsche Bank. "Deutsche Bank Location Finder". Deutsche Bank. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- "Top 50 Largest Banks in the World". relbanks.com. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- For the history of Deutsche Bank, in general, see Lothar Gall (et al.), The Deutsche Bank 1870–1995, London (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) 1995.

- James, Harold. "Deutsche Bank Isn't Deutsch Anymore". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Statut der Deutschen Bank Aktien-Gesellschaft, Berlin 1870, pp. 3–4.

- James, H (13 September 2004). The Nazi Dictatorship and the Deutsche Bank. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521838746. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Manfred Pohl / Angelika Raab-Rebentisch, Die Deutsche Bank in Bremen 1871–1996, Munich, Zurich (Piper) 1996.

- Manfred Pohl / Angelika Raab-Rebentisch, Die Deutsche Bank in Hamburg 1872–1997, Munich, Zurich (Piper) 1997.

- Deutsche Bank in China, Munich (Piper) 2008.

- Manfred Pohl / Kathleen Burk, Deutsche Bank in London 1873–1998, Munich, Zurich (Piper) 1998.

- Christopher Kobrak, Banking on Global Markets. Deutsche Bank and the United States, 1870 to the Present, New York (Cambridge University Press) 2008.

- A Century of Deutsche Bank in Turkey, Istanbul 2008, pp. 21–27.

- Historische Gesellschaft der Deutschen Bank (ed.), Die Deutsche Bank in Frankfurt am Main, Munich, Zurich (Piper) 2005.

- Manfred Pohl / Angelika Raab-Rebentisch, Die Deutsche Bank in Leipzig 1901–2001, Munich, Zurich (Piper) 2001.

- Manfred Pohl, Deutsche Bank Buenos Aires 1887–1987, Mainz (v. Hase & Koehler) 1987.

- Maximilian Müller-Jabusch, 50 Jahre Deutsch-Asiatische Bank 1890–1939, Berlin 1940.

- Plumpe, Werner; Nützenadel, Alexander; Schenk, Catherine (5 March 2020). Deutsche Bank: The Global Hausbank, 1870 – 2020. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-4729-7730-4.

- Whittington, Richard; Mayer, Michael (2002). The European Corporation: Strategy, Structure, and Social Science. Oxford University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-19-925104-9.

- "TWO LEADING BANKS COMBINE IN BERLIN; Deutsche and Disconto Gesellschaft Form Biggest of Kind in German History.285,000,000-MARK CAPITALCombined Deposits 4,000,000,000----Believed Forerunner of OtherFinancial Consolidations. Announcement of Merger. One Employed 14,000 Persons". The New York Times. 27 September 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Deutsche Bank Resumes Name". The New York Times. 9 September 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Geschichte – Deutsche Bank". db.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2005.

- Schmid, John (5 February 1999). "Deutsche Bank Linked To Auschwitz Funding". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- "$5.2 Billion German Settlement". 15 December 2004. Archived from the original on 8 September 2006. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- For a detailed account of Deutsche Bank's involvement with the Nazis see: Harold James. The Nazi Dictatorship and the Deutsche Bank. Cambridge University Press, 2004, 296 pp., ISBN 0-521-83874-6.

- "La bella banca" (PDF). Bankgeschichte.de. February 2018.

- Moyer, Liz (30 October 2007). "Super-Size That Severance". Forbes. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Andrews, Edmund L. (1 December 1998). "Bank Giant: The Overview; Deutsche Gets Bankers Trust for $10 Billion". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Reuters (27 November 1993). "Company News; Deutsche Bank Announces Big Expansion in Italy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- "The Deutsche Bank building: Tombstone at Ground Zero – Mar. 20, 2008". 2 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "Lower Manhattan : 130 Liberty Street". 28 March 2011. Archived from the original on 28 March 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Brinded, Lianna (11 November 2014). "Bank of Cyprus Funded and Controlled by Ex-KGB, Billionaires and Controversial Former Financiers". International Business Times UK. Archived from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Protess, Ben; Silver-Greenberg, Jessica; Drucker, Jesse (19 July 2017). "Big German Bank, Key to Trump's Finances, Faces New Scrutiny". New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "Scudder PIC joins Deutsche Bank's private banking". bizjournals.com. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Harding, Luke (21 December 2017). "Is Donald Trump's Dark Russian Secret Hiding in Deutsche Bank's Vaults?". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 9 November 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Sampathkumar, Mythili (14 April 2017). "Former MI6 chief Richard Dearlove says Donald Trump borrowed money from Russia during 2008 financial crisis: Days before taking office, Mr Trump said Russia had never had any 'levarage' over him". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "Сын главы ВТБ Андрей Костин разбился на квадроцикле: 32-летний банкир погиб на отдыхе в Ярославской области" [The son of the head of VTB Andrei Kostin crashed on a quad: 32-year-old banker died on holiday in the Yaroslavl region]. Izvestia (in Russian). 2 July 2011. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Шипилов, Евгений; Танас, Ольга (4 July 2011). "Погиб на трезвую голову: В ДТП погиб сын президента ВТБ Андрей Костин" [Killed sober: The accident killed the son of the president of VTB Andrei Kostin]. Gazeta (in Russian). Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Corcoran, Jason (22 December 2011). "Putin Pushing Russian Banks Points 'Two Tanks' at Western Firms". Bloomberg Businessweek. London.

- Rapoza, Kenneth (12 October 2011). "Russian Bank Heads To New York". Forbes. New York City. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- McLannahan, Ben; Scannell, Kara; Silverman, Gary (30 August 2017). "Donald Trump's debt to Deutsche Bank". Financial Times. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Haberman, Maggie; Liptak, Adam (28 June 2018). "Inside the White House's Quiet Campaign to Create a Supreme Court Opening". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- Locke, Benjamin (29 June 2018). "A shocking report just revealed disturbing secret relationship between Trump and Justice Kennedy's son". Washington Press. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- Harding, Luke; Kirchgaessner, Stephanie; Hopkins, Nick; Smith, David (16 February 2017). "Deutsche Bank examined Donald Trump's account for Russia links". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- Gaines, carl (6 February 2013). "Deutsche Bank's Rosemary Vrablic and Private Banking's Link to CRE Finance". Commercial Observer. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- "Unprofitable Vegas casino sold by Deutsche Bank for $1.73 billion". The Las Vegas News.Net. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Levin–Coburn report on Wall Street and the Financial Crisis" (PDF). US Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. 13 April 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2011.

- "Deutsche Bank Settles with US Shareholders". Market Watch. 3 January 2014.

- Braithwaite, Tom; Scannell, Kara; Mackenzie, Michael (5 December 2012). "Deutsche hid up to $12bn losses, say staff". Financial Times.

- Braithwaite, Tom; Mackenzie, Michael; Scannell, Kara (5 December 2012). "Deutsche Bank: Show of strength or a fiction?". Financial Times.

- Böll, Sven; Hawranek, Dietmar; Hesse, Martin; Jung, Alexander; Neubacher, Alexander; Reiermann, Christian; Sauga, Michael; Schult, Christoph; Seith, Anne; Sultan, Christopher (translator) (25 June 2012). "Imagining the Unthinkable. The Disastrous Consequences of a Euro Crash". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Subscribe to read". Financial Times.

- Javers, Eamon (15 March 2009). "AIG ships billions in bailout abroad". politico.com. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- "Deutsche Bank Said to Be Ordered by EU to Close $1.7 Billion Capital Gap". Bloomberg. 28 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- "Deutsche Bank reports core capital ratio of 11.9% despite 2016 full-year net loss of EUR 1.4 billion – Newsroom". db.com.

- "When Deutsche Bank sneaks out its results on a Sunday night, they can't be good". Quartz. 19 January 2014.

- "Deutsche Bank Plans to Eliminate Dividend for Two Years in Overhaul". 29 October 2015.

- "Deutsche Bank cutting 15,000 jobs as new CEO sets out strategy plan". 29 October 2015.

- "Deutsche Bank appoints John Cryan to succeed Jürgen Fitschen and Anshu Jain". Deutsche Bank. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- "Jain Era Ending as Deutsche Bank Appoints Cryan for Top Job". Bloomberg. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "Deutsche Bank reports preliminary full year and fourth quarter 2015 results – Newsroom". db.com.

- "Can Cryan halt Deutsche Bank's decline?". Euromoney. March 2016.

- "HNA Group, Secretive Chinese Conglomerate, Takes Top Stake in Deutsche Bank". The New York Times. 3 May 2017.

- Harding, Luke (29 November 2018). "Deutsche Bank offices raided in connection with Panama Papers". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- "Deutsche Bank CEO Signals More Cuts to Investment Bank". Wall Street Journal. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

... "tough cutbacks" at the troubled lender’s investment bank, his strongest public admission yet that the business needs a dramatic overhaul.

- "Deutsche Bank, in a Last-Ditch Effort to Stop Its Spiral, Could Lay Off 20,000". New York Times. 28 June 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

Other investment-banking divisions also could be slashed, including the bond-trading business and teams that specialize in selling and trading various types of derivatives.

- "Deutsche Bank Plans to Cut as Many as 20,000 Jobs in Revamp". Bloomberg. 30 June 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

The bank expects to make a formal announcement no later than July 8, one person said. The Wall Street Journal first reported on the plan to cut as many as 20,000 jobs.

- "Deutsche Bank Discusses Lower Capital Buffer With Regulators". Bloomberg. 1 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

...including the loss of as many as 20,000 jobs over the coming years ... The cost could run into the billions of euros, analysts estimate

- "Deutsche Bank starts cull of 18,000 jobs". Financial Times. 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

German lender begins its most radical strategic overhaul in two decades

- Farrell, Sean; Kollewe, Julia; Helmore, Edward (8 July 2019). "Deutsche Bank starts cutting London jobs with 18,000 at-risk worldwide". theguardian.com.

- "Deutsche Bank Cuts Investment Bank Bonuses About 30%". Bloomberg. 17 January 2020.

- "Deutsche Bank Annual Report". Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- "Neue Führung: Christian Sewing wird Chef der Deutschen Bank". Spiegel Online. 8 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Bray, Chad (19 May 2016). "Jürgen Fitschen to Stay With Deutsche Bank in New Role". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- Dakers, Marion (2017). "Former Deutsche Bank boss Anshu Jain takes up new role at Cantor Fitzgerald". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- Germany, Süddeutsche de GmbH, Munich. "Der Außenminister, der Kanzler-Neffe und Mr. Peanuts". Süddeutsche.de (in German). Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Banken: Chronologie: Vorstandssprecher der Deutschen Bank". Die Zeit (in German). 31 May 2012. ISSN 0044-2070. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Deutsche Bank fliegt aus Stoxx Europe 50". manager magazin (in German). Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "EURO STOXX 50® INDEX" (PDF). stoxx.com. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "Annual Report 2006 / Related Party Transactions". annualreport.deutsche-bank.com. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "Shareholder Structure – Deutsche Bank". db.com. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Deutsche Bank Corporate & Investment Bank". db.com. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Deutsche Bank sells chunk of Polish business to Santander". Financial Times. 14 December 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Deutsche Bank To Sell Portuguese Private and Commercial Clients Business To Abanca". Reuters. 27 March 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- The Financial (28 May 2018). "Germany's biggest Private & Commercial Bank is launched". finchannel.com. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- "Wealth Management – Locations". Deutsche Bank. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Deutsche Bank Logo: Design and History". Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- "Deutsche Bank: Neuer Skandal | Börse Aktuell". Boerse.ARD.de. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "Steuerbetrug: Sechs Ex-Mitarbeiter der Deutschen Bank verurteilt". Die Zeit. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Crawford, David; Karnitschnig, Matthew (3 August 2009). "Bank Spy Scandal Widens". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- "Deutsche Bank undertakes independent investigation" (Press release). duetsche-bank.de. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- "Deutsche Bank gives update on inquiries" (Press release). deutsche-bank.de. 22 July 2009. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- "Press release Public Prosecutor's Office in Frankfurt" (Press release). sta-frankfurt.justiz.hessen.de. 8 October 2009. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- "Deutsche Bank Probe Finds Individual Misconduct". The Wall Street Journal. 18 December 2009. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- "Ethics & Economics – Black Planet Dossier 2013 DEUTSCHE BANK". ethecon.org. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- "Deutsche Bank receives Black Planet Award at AGM". Banktrack. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Protess, Ben; Jack Ewing (23 April 2015). "Deutsche Bank to Pay $2.5 Billion Fine to Settle Rate-Rigging Case". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- "Deutsche Bank fined record $2.5 billion in rate rigging inquiry". Reuters. 23 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Freifeld, Karen. "Deutsche Bank agrees to $7.2 billion mortgage settlement with U.S." Reuters. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Deutsche Bank to pay US$258m for violating US sanctions". Channel NewsAsia. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "NYDFS Announces Deutsche Bank to Pay $258 Million, Install Independent Monitor, Terminate Employees for Transactions on Behalf of Iran, Syria, Sudan, Other Sanctioned Entities". New York State Department of Financial Services. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "Deutsche Bank fined $258m for violating US sanctions". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "Deutsche Bank ordered to pay US over $250mn for violating sanction regime". RT. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- Tabuchi, Hiroko (7 November 2016). "Environmentalists Target Bankers Behind Pipeline". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- "Call on Deutsche Bank to Divest from DAPL". Action Network. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- "Preservation of sensitive, protected sites". db.com. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- "DFS Fines Deutsche Bank $425 Million for Russian Mirror-Trading Scheme". Dfs.ny.gov. 30 January 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Jill Treanor. "Deutsche Bank fined $630m over Russia money laundering claims | Business". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Thomas, Landon, Jr. (30 January 2017). "Deutsche Bank Fined for Helping Russians Launder $10 Billion". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- Wang, Christine (30 January 2017). "Deutsche Bank to pay $425 million fine over Russian money-laundering scheme: New York regulator". CNBC. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "Deutsche Bank Ends N.Y. Mirror-Trade Probe for $425 Million". Bloomberg L.P. 30 January 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- Enrich, David; Protess, Ben; Rashbaum, William K.; Weiser, Benjamin (5 August 2020). "Trump's Bank Was Subpoenaed by N.Y. Prosecutors in Criminal Inquiry" – via NYTimes.com.

- Smith, Allan (8 December 2017). "Trump's long and winding history with Deutsche Bank could now be at the center of Robert Mueller's investigation". Business Insider. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Enrich, David (18 March 2019). "A Mar-a-Lago Weekend and an Act of God: Trump's History With Deutsche Bank". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Enrich, David (18 March 2019). "Deutsche Bank and Trump: $2 Billion in Loans and a Wary Board". Retrieved 8 November 2019 – via NYTimes.com.

- Buchanan, Larry; Yourish, Karen (25 September 2019). "Tracking 30 Investigations Related to Trump". New York Times. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- Flitter, Emily; Enrich, David (15 April 2019). "Deutsche Bank Is Subpoenaed for Trump Records by House Democrats". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Kara Scannell and Jeremy Herb (16 April 2019). "House committees issue subpoenas to Deutsche Bank, JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Bank of America to probe Trump's finances". CNN.com. Retrieved 16 April 2019.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Zachary Warmbrodt and John Bresnahan (15 April 2019). "House Democrats subpoena Deutsche Bank in Trump investigation". Politico.com. Retrieved 16 April 2019.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Hosenball, Mark; Beech, Eric; Zargham, Mohammad; Osterman, Cynthia; Adler, Leslie (15 April 2019). "House panels issue subpoenas to Deutsche Bank, others in Trump probe". Reuters.com. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Demijian, Karoun (15 April 2019). "House Democrats subpoena Deutsche Bank, other financial institutions tied to Trump". WashingtonPost.com. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Alesci, Cristina (30 April 2019). "Trump team sues Deutsche Bank and Capital One to keep them from turning over financial records to Congress". CNN. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- Flitter, Emily; McKinley, Jesse; Enrich, David; Fandos, Nicholas (22 May 2019). "Trump's Financial Secrets Move Closer to Disclosure" – via NYTimes.com.

- Merle, Renae (28 May 2019). "House subpoenas for Trump's bank records put on hold while president appeals". Washington Post. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- "Deutsche Bank tells U.S. court it does not have Trump's tax returns". 11 October 2019 – via www.reuters.com.

- Enrich, David (3 December 2019). "Trump Loses Appeal on Deutsche Bank Subpoenas" – via NYTimes.com.

- Enrich, David (19 May 2019). "Deutsche Bank Staff Saw Suspicious Activity in Trump and Kushner Accounts". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- Mullen, Jethro (31 January 2017). "Deutsche Bank fined for $10 billion Russian money-laundering scheme". CNN Money. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- Levai, Scott Stedman and Eric (27 November 2019). "Deutsche Bank Executive Who Signed Off On Trump Loans Kills Himself At Age 55".

- Flitter, Emily; Enrich, David (15 April 2019). "Deutsche Bank Is Subpoenaed for Trump Records by House Democrats". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Los Angeles County Medical Examiner-Coroner".

- David Enrich [@davidenrich] (10 July 2019). "Exclusive: @DeutscheBank had an extensive relationship with Jeffrey Epstein, lending him money and providing trading services — up until May 2019, when the bank cut him off.www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/business/jeffrey-epstein-net-worth.html" (Tweet). Retrieved 11 July 2019 – via Twitter.

- Stewart, James B.; Goldstein, Matthew; Kelly, Kate; Enrich, David (10 July 2019). "Jeffrey Epstein's 'Infinite Means' May Be a Mirage". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- Metcalf, Tom; Robinson, Matt (10 July 2019). "Deutsche Bank ended its relationship with Jeffrey Epstein this year". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- Enrich, David; Becker, Jo (23 July 2019). "Jeffrey Epstein Moved Money Overseas in Transactions His Bank Flagged to U.S." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- Hong, Jenny Strasburg and Nicole. "Jeffrey Epstein's Financial Trail Goes Through Deutsche Bank". WSJ. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- Goldstein, Matthew (7 July 2020). "Deutsche Bank Settles Over Ignored Red Flags on Jeffrey Epstein". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Superintendent Lacewell Announces DFS Imposes $150 Million Penalty on Deutsche Bank in Connection with Bank's Relationship with Jeffrey Epstein and Correspondent Relationships with Danske Estonia And FBME Bank". Department of Financial Services (Press release). 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Update: Criminal cartel charges to be laid against Deutsche Bank". ACCC. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- "Update: Criminal cartel charges to be laid against Citigroup". ACCC. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Jensen, Teis; Gronholt-Pedersen, Jacob (19 November 2018). "Danske whistleblower says big European bank handled $150 billion in..." Reuters. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Arons, Steven; Barnert, Jan-Patrick; Comfort, Nicholas (20 November 2018). "Deutsche Bank Hits Record Low on New Worry Over Danske Role". bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "SEC.gov | Deutsche Bank to Pay Nearly $75 Million for Improper Handling of ADRs". sec.gov. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Deutsche to pay $75 million to settle ADRs abuses case, U.S. SEC says". Reuters. 20 July 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- Strasburg, Aruna Viswanatha, Bradley Hope and Jenny. "U.S. Investigating Deutsche Bank's Dealings With Malaysian Fund 1MDB". WSJ. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- Flitter, Emily (10 July 2019). "Deutsche Bank Caught Up in Scandal Over Malaysian 1MDB Fund". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- "Acquisition of Bankers Trust Successfully Closed". Deutsche-bank.de. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- "Deutsche Asset & Wealth Management – Real Estate Investment Management". rreef.com. 16 January 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2005. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- "Deutsche Bank to acquire RREEF for $490 million". nreionline.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010.

- "interstitials | Business solutions from". AllBusiness.com. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- "Acquisition of Chapel Funding". Deutsche-bank.de. 12 September 2006. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- "Acquisition of MortgageIT Holdings". Deutsche-bank.de. 28 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- "Deutsche Bank wins control of Postbank". Financial Times. London.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Deutsche Bank. |