Corruption in Armenia

Corruption in Armenia is a widespread and growing problem in Armenian society. Council of Europe's Group of States Against Corruption in its fourth evaluation round noted that corruption remains an important problem for Armenian society.[1] Cases of bribery in the extremely corrupt court are just one of the major forms that corruption takes in this country.

| Political corruption | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Concepts | ||||||||||||

| Corruption by country | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Extent

In 2017 there were 634 corruption related criminal cases registered (up from 428 in 2016), which led to criminal persecution of 376 persons.[2]

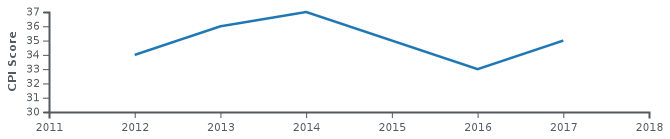

In 2017 Armenia scored 35 on Corruption Perceptions Index and was positioned 107th out of 180 countries.[3][4] Following chart represents score of Armenia in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index, higher is better.[5]

According to Transparency International 2014 report, entrenched corruption, strong patronage networks, a lack of clear separation between private enterprise and public office, as well as the overlap between political and business elites in Armenia render the implementation of anti-corruption efforts relatively inefficient and feed a pervasive political apathy and cynicism on the part of citizens, who do not see an impactful role for themselves in the fight against corruption.[6]

In 2006 the United Nations Development Programme in Armenia views corruption in Armenia as "a serious challenge to its development."[7] The selective and non-transparent application of tax, customs and regulatory rules, as well as weak enforcement of court decisions fuels opportunities for corruption. The Armenian procurement system is characterised by instances of unfair tender processes and preferential treatment. Relationship between high-ranking government officials and the emerging private business sector encourage influence peddling. The government has reportedly failed to fund implementation of the anti-corruption strategy and devoted no money and little commitment for anti-corruption efforts.

Anti-corruption institutions

The main anti-corruption institutions of the Armenian government are an Anti-Corruption Council – headed by the prime minister – and the Anti-Corruption Strategy Monitoring Commission, established in June 2004 to strengthen the implementation of anticorruption policy. However, these institutions scarcely functioned in 2006-2007, even though they were supposed to meet twice-quarterly and monthly, respectively.[8] Furthermore, Armenian Anti-Corruption Council was accused of lavish spending and has largely failed to investigate or prosecute senior officials.[9][10]

History

The late Prime Minister Andranik Margarian launched Armenia’s first post-Soviet campaign against corruption in 2003. The initiative, however, has been widely disparaged for being short on results.[11] Former Prime Minister Tigran Sargsyan has acknowledged that corruption is Armenia’s "number one problem that obstructs all our reforms."[11]

The government has recently launched an anti-graft campaign which has been accompanied by changes in customs regulations, reported tax police inspections of companies owned by pro-government businesspeople and numerous high-profile firings of people in the tax department, customs service and police. The recent crackdown on corruption has received mixed reactions.[11]

Areas

Courts

Corruption takes the form of bribery in Armenian courts. If you have relative judges or can give bribes ranging from a few hundred to thousands of US dollars, you can easily get the judge to let you win the case. This has resulted in a large portion of repatriated Armenians from the USA an many other countries to lose everything they bring to the country and worked very hard for.

Mining

Regulation of mineral industry in Armenia carries multiple corruption risks, as it was highlighted by international research.[12]

Education

Despite the success of the authorities in reducing petty corruption/bribery in some citizen-government interactions, anti-corruption watchdogs report that entrenched corruption, strong patronage networks, a lack of clear separation between private enterprise and public office, as well as the overlap between political and business elites limit the effective implementation of anti-corruption efforts. These problems affect the education system too. It is perceived as one of the sectors that is hit hardest by corruption. Attempts to fight the problem have brought mixed results and often opened new opportunities for malpractice instead of closing the existing ones.[13][14]

Tax and customs agencies

In 2007, World Bank economists pointed to serious problems with rule of law and widespread corruption in the Armenian tax and customs agencies.[15]

Misappropriation of international loans

In March 2004, an ad hoc commission of the Armenian parliament investigating the use of a $30 million World Bank loan concluded that mismanagement and corruption among government officials and private firms was the reason of the failure of the program to upgrade Yerevan's battered water infrastructure.[16] The World Bank issued the loan in 1999 in order to improve Yerevan residents' access to drinking water. The government promised to ensure around-the-clock water supplies to the vast majority of households by 2004, but as of 2008, most city residents continue to have running water for only a few hours a day.[16]

Veolia Environnement, the French utility giant that took over Yerevan's loss-making water and sewerage network in 2006, has said that it will need a decade to end water rationing.[16] In August 2007, Bruce Tasker, a Yerevan-based British engineer who had participated in the parliamentary inquiry as an expert, publicly implicated not only Armenian officials and businessmen but also World Bank representatives in Yerevan in the alleged misuse of the loan. In an October 4, 2007 news conference, the World Bank Yerevan office head Aristomene Varoudakis denied the allegations, claiming that the World Bank disclosed fully all information available on the project to the parliamentary commission and that based on this information there was no evidence of fraud or mismanagement in the project.[16]

Illegitimate use of eminent domain

Eminent domain laws[17] have been used to forcefully remove residents, business owners, and land owners from their property. The projects that finally are built on the site are not of state interest, but rather are privately owned by the same authorities who have executed the eminent domain clause. A prominent example is the development of Yerevan's central Northern Avenue area. Another involves an ongoing project (as of November 2008) to construct a trade center near Yerevan's botanical garden. The new land owners are non other than Yerevan's mayor Yervand Zakharyan and Deputy Mayor Karen Davtyan, who was at one time Director of the Armenian Development Agency and successfully executed the eviction of residents on Northern Avenue.[18]

Traffic police and extortion

Traffic police residing along major highways, such as those connecting traffic between Tbilisi and Yerevan frequently extort passing traffic for bribes in exchange for forgiving "traffic violations". Tourists are especially targeted, with the police openly requesting ~5,000 Armenian Dram per bribe. Violations are often fabricated, and police target local and foreign drivers alike.

See also

References

- "FOURTH EVALUATION ROUND on Armenia".

- "Criminal statistics of 2017 summary by Armstat" (PDF).

- e.V., Transparency International. "Transparency International - Armenia". www.transparency.org. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- "Corruption Perception Index 2017".

- e.V., Transparency International. "Corruption Perceptions Index 2017". www.transparency.org. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- "TI's 2014 National Integrity System Assessment Armenia".

- "Strengthening Cooperation between the National Assembly, Civil Society and the Media in the Fight Against Corruption" Archived 2006-05-02 at the Wayback Machine, Speech by Ms. Consuelo Vidal, (UN RC / UNDP RR), April 6, 2006.

- Global Corruption Report 2008 Archived 2010-09-03 at the Wayback Machine, Transparency International, Chapter 7.4, p. 225.

- Grigoryan, Marianna (2015-08-12). "Armenia's anti-corruption council accused of lavish spending". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- "The Guardian: Armenia's anti-corruption council accused of lavish spending". Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- "ARMENIA: GETTING SERIOUS ABOUT CORRUPTION?" Archived 2008-07-27 at the Wayback Machine, EurasiaNet, July 11, 2008.

- e.V., Transparency International. "TI Publication - Combatting corruption in mining approvals". www.transparency.org. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- Strengthening integrity and fighting corruption in education: Armenia, Open Society Foundations - Armenia and Center for Applied Policy, 2015

- Armenia,3 Round of Monitoring of the Istanbul Action Plan, OECD Publishing, 2014

- World Bank Urges ‘Second Generation Reforms’ In Armenia, Armenia Liberty (RFE/RL), March 20, 2007.

- Corruption Chronicles: International Loans, Eurasianet.org, 2008.

- The Constitution of the Republic of Armenia (27 November 2005), Chapter 2: Fundamental Human and Civil Rights and Freedoms, Article 31 Archived 27 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- The Yerevan Municipality Allocates a Parcel of Land to one of its Employees under the Guise of “Eminent Domain” Archived 2009-08-21 at the Wayback Machine, Hetq Online, November 10, 2008.