Incitement to genocide

Incitement to genocide is a crime under international law which prohibits inciting (encouraging) the commission of genocide. An extreme version of hate speech, incitement to genocide is considered an inchoate offense and is theoretically subject to prosecution even if genocide does not occur, although charges have never been brought in an international court without mass violence having occurred. "Direct and public incitement to commit genocide" was forbidden by the Genocide Convention in 1948. Incitement to genocide is often cloaked in metaphor and euphemism and may take many forms beyond direct advocacy, including dehumanization and "accusation in a mirror". Historically, incitement to genocide has played a significant role in the commission of genocide, including the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust and the Rwandan genocide. However, it may occur in the absence of genocide.

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

| Issues |

| Genocide of indigenous peoples |

|

| Late Ottoman genocides |

| World War II (1941–1945) |

| Cold War |

|

| Genocides in postcolonial Africa |

|

| Ethno-religious genocide in contemporary era |

|

| Related topics |

| Category |

Definition

"Direct and public incitement to commit genocide" was forbidden by the Genocide Convention (1948), Article 3(c).[1] If genocide was committed, incitement could also be prosecuted as complicity in genocide, prohibited in Article 3(e), without the requirement to be direct or public.[2]

Incitement

Incitement means encouraging someone else to commit a crime, in this case genocide.[3] The Genocide Convention is generally interpreted as requiring intent to cause genocide for incitement prosecutions.[4]

"Direct"

"Direct" means that the speech must be both intended and understood as a call to take action against the targeted group, which may be difficult to prove for prosecutors due to cultural and individual differences.[3] Wilson notes that "direct" does not inherently exclude euphemisms (see below), "if the prosecution can show that the overwhelming majority of listeners understood a euphemistic form of speech as a direct (rather than circuitous, oblique or veiled) call to commit genocide".[5] American genocide scholar Gregory Gordon, noting that most incitement does not take the form of imperative command to kill the target group (see below), recommends that "glossary of incitement techniques should be woven into judicial pronouncements".[6]

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia came to different conclusions on the prosecution of incitement. According to ICTR, incitement did not require an explicit call for violence against the targeted group or casually connected subsequent violence. ICTY came to the opposite conclusion in Prosecutor v. Kordić, because "hate speech not directly calling for violence... did not rise to the same level of gravity" as crimes against humanity.[7]

"Public"

Incitement is considered "public" "if it is communicated to a number of individuals in a public place or to members of a population at large by such means as the mass media".[3] However, the Genocide Convention never defines the term "public" and it is unclear how the criterion would apply to new technologies, such as social media.[8] Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza was convicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda for speeches made at a roadblock, but on appeal it was ruled that these speeches were not considered public.[9]

Causation

Incitement to genocide is an inchoate crime as it is technically prosecutable even if genocide is never committed.[10][11][12] However, Gordon writes that "no international court has ever brought an incitement prosecution in the absence of a subsequent genocide or other directly-related large-scale atrocity".[13] Wilson noted that the judgement against Jean-Paul Akayesu "seemingly elevated causation to a legal requirement to prove incitement" as it stated "there must be proof of a possible causal link" between the alleged incitement and murders.[14] Tribunals assert that the incitement led to violence, even when this is not conclusively proven by the prosecution.[15][16]

Davies details four benefits of an inchoate and separate approach to prosecuting incitement, compared to considering incitement part of the crime of genocide: obviating the difficult task of proving a causal connection between incitement and violence, allowing people to be charged with aiding and abetting incitement, allowing incitement to genocide to be prosecuted even when the resulting violence cannot be proven to have been genocidal (rather than merely war crimes or crimes against humanity), and enabling the prevention of genocide by prosecuting incitement before genocide results.[17]

Free speech issues

Defining incitement to genocide is important because it can be in tension with the protection of free speech. In the Léon Mugesera case, a Canadian federal appeals court found that his 1992 speech claiming that Hutus were about to be "exterminated by inyenzi or cockroaches" was protected free speech and that the speech's themes were "elections, courage and love", but the Canadian Supreme Court ruled that "reasonable grounds exist to believe that Mr. Mugesera committed a crime against humanity".[18][19] Some dictators have used overly broad interpretations of "incitement" in order to jail journalists and political opponents.[20]

Gordon argued that the benefits of free speech do not apply in situations where mass violence is occurring because "the 'marketplace of ideas' has been likely shut down or is not functioning properly." Therefore, it is justified to restrict speech that would not ordinarily be punishable.[21] Susan Benesch, a free speech advocate, concedes that free speech provisions are intended to protect private speech while most or all genocide is state-sponsored. Therefore, in her opinion, prosecution of incitement to genocide should take into account the authority of the speaker and whether they are likely to persuade the audience.[22][23] Richard Ashby Wilson observed that those prosecuted for incitement to genocide and related international crimes "have gone beyond mere insult, libel and slander to incite others to commit mass atrocities. Moreover, their utterances usually occur in a context of an armed conflict, genocide and a widespread or systematic attack on a civilian population."[24]

Alternate definitions

Alternate definitions and interpretations have been proposed by various authors. In Benesch's six-pronged "reasonably probable consequences" test, a finding of incitement to genocide would require violence as a possible consequence of the speech,[16][25] which is compatible with existing jurisprudence.[26] Carol Pauli's "Communications Research Framework" is intended to define situations where freedom of speech can be justifiably infringed by broadcast interference and other non-judicial measures to prevent genocide.[27] Gordon has argued for "fixing the existing framework" by reinterpreting or changing incitement, direct, public, and causation elements.[28] Gordon favors removing the requirement to be public, because "[p]rivate incitement can be just as lethal, if not more, than public."[29]

Types

Susan Benesch noted that "Inciters have used strikingly similar techniques before genocide, even in times and places as different as Nazi Germany in the 1930s and Rwanda in the 1990s."[30] The following types have been classified by Gordon.[31]

Direct advocacy

Gordon notes that "direct calls for destruction are relatively rare".[32] In May 1939, Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher wrote "A punitive expedition must come against the Jews in Russia. A punitive expedition which will provide the same fate for them that every murderer and criminal must expect. Death sentence and execution. The Jews in Russia must be killed. They must be exterminated root and branch."[33] On 4 June 1994, Kantano Habimana broadcast from RTLM: "we will kill the Inkotanyi and exterminate them" based on their alleged ethnic characteristics: "Just look at his small nose and then break it".[34][32] Gordon considers Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's 2005 comments that Israel "must be wiped off the map" an example of direct advocacy.[32]

Predictions

In the Rwandan Media Case, some broadcasts of the Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) that "foretold elimination of the inyenzi or cockroaches" were found to constitute incitement to genocide. An example is the following statement by Ananie Nkurunziza on RTLM on 5 June 1994: "I think we are fast approaching what I would call dawn … dawn, because—for the young people who may not know— dawn is when the day breaks. Thus when day breaks, when that day comes, we will be heading for a brighter future, for the day when we will be able to say “There isn’t a single Inyenzi left in the country.” The term Inyenzi will then be forever forgotten, and disappear for good."[32]

Dehumanization

According to Gordon, "verminization, pathologization, demonization, and other forms of dehumanization" can be considered incitement to genocide. Verminization classifies the target as something "whose extermination would be considered normal and desirable",[35] which is why Hutu leaders frequently described Tutsis as inyenzi (cockroaches). RTLM propagandist Georges Ruggiu pled guilty to incitement to genocide, admitting that calling Tutsis "inyenzi" meant designating them "persons to be killed".[35] Gordon writes that like dehumanization, demonization is "sinister figurative speech but is more phantasmagorical and/ or anthropocentric in nature... [centering] on devils, malefactors, and other nefarious personages."[36] Pathologization means designating the target as a disease. According to genocide scholar Gregory Stanton, this "expropriates pseudo-medical terminology to justify massacre [and it] dehumanizes the victims as sources of filth and disease, [propagating] the reversed social ethics of the perpetrators".[35][37] Stanton identified dehumanization as third in the eight stages of genocide, noting that "Dehumanization overcomes the normal human revulsion against murder." While Stanton and others have contended that dehumanization is a necessary condition for genocide,[38] Johannes Lang has argued that its role is overstated and that forms of humiliation and torture which occur during genocide occur precisely because the victims' humanity is recognized.[39]

"Accusation in a mirror"

"Accusation in a mirror" is a false claim that accuses the target of something that the perpetrator is doing or intends to do.[36][40] The name was coined by an anonymous Rwandan propagandist in Note Relative à la Propagande d’Expansion et de Recrutement. Drawing on the ideas of Joseph Goebbels and Vladimir Lenin, he instructed collagues to "impute to enemies exactly what they and their own party are planning to do".[40][41][42] By invoking collective self-defense, propaganda justifies genocide, just as self-defense is a defense for individual homicide.[40] Susan Benesch remarked that while dehumanization "makes genocide seem acceptable", accusation in a mirror makes it seem necessary.[43]

Kenneth L. Marcus writes that the tactic is "similar to a false anticipatory tu quoque" (a logical fallacy which charges the opponent with hypocrisy). The tactic does not rely on what misdeeds the enemy could plausibly be charged with, based on actual culpability or stereotypes, and does not involve any exaggeration but instead is an exact mirror of the perpetrator's own intentions. The weakness of the strategy is that it reveals the perpetrator's intentions, perhaps before he is able to carry it out. This could enable intervention to prevent genocide, or alternatively be "an indispensable tool for identifying and prosecuting incitement".[44] According to Marcus, despite its weaknesses the tactic is frequently used by genocide perpetrators (including Nazis, Serbs, and Hutus) because it is effective. He recommends that courts should consider a false accusation of genocide by an opposing group to satisfy the "direct" requirement, because that is an "almost invariable harbinger of genocide".[45]

Euphemism and metaphor

Perpetrators often rely on euphemisms or metaphors to conceal their actions.[46] During the Rwandan genocide, calls to "go to work" referred to the murder of Tutsis.[46][43] In Prosecutor v. Nyiramasuhuko, et al. (2015), two defendants had asked others to "sweep the dirt outside".[36] The Trial Chamber of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) held that this was incitement to genocide, because listeners "understood the words … 'sweeping dirt', to mean they needed to kill Tutsis".[36] Similarly, in Nazi Germany euphemisms such as Final Solution, special treatment, and "resettlement to the East" were used to refer to mass murder.[47] According to William Schabas, "The history of genocide shows that those who incite the crime speak in euphemisms."[46]

Justification

Justifying ongoing atrocities may be considered incitement to genocide. For example, Nazi propagandists repeatedly emphasized to potential perpetrators that "massacres, torture, death marches, slavery, and other atrocities" were carried out in a "humane" way. According to W. Michael Reisman, "in many of the most hideous international crimes, many of the individuals who are directly responsible operate within a cultural universe that inverts our morality and elevates their actions to the highest form of group, tribe, or national defense".[46][43]

Praising past violence

Praising the perpetrators of completed atrocities can be a form of incitement. RTLM announcer Georges Ruggiu thanked the "valiant combatants" supposedly fighting a "battle" against Tutsi civilians. Eliézer Niyitegeka, transport minister, thanked militias for their "good work".[48]

Asking questions

In the Rwandan genocide, Simon Bikindi's loudspeaker broadcasts to militia asking "have you killed the Tutsis here?" were held to contribute to a finding of incitement to genocide.[48]

Conditional advocacy

In January 1994, Hassan Ngeze wrote an article stating that if Tutsi militias attacked, there would be "none of them left in Rwanda, not even a single accomplice. All the Hutu are united". The ICTR found that this was incitement to genocide, even though it was conditional.[48]

Target–sympathizer conflation

During genocide, members of the majority group who help or sympathize with the targeted group are also persecuted. For example, during the Holocaust, non-Jews who hid Jews or simply opposed the genocide were murdered. In Rwanda, Hutus who opposed the genocide were labeled "traitors" and murdered.[49][43] Mahmoud Ahmadinejad also threatened sympathizers with Israel, stating "Anybody who recognizes Israel will burn in the fire of the Islamic nation’s fury".[49]

Causing genocide

According to Gregory Stanton, "one of the best predictors of genocide is incitement to genocide".[50] According to Susan Benesch, the strongest evidence for a causal connection between incitement and genocide is found in cases where there is widespread civilian participation in killings (as in Rwanda or the Nazi Holocaust) and where the target group lives alongside a majority group, requiring the acquiescence of that group for genocide to occur.[51] Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn wrote that "in order to perform a genocide the perpetrator has always had to first organize a campaign that redefined the victim group as worthless, outside the web of mutual obligations, a threat to the people, immoral sinners, and/or subhuman."[52]

Larry May argues that incitement to genocide is proof of genocidal intent,[53] and that inciters (along with planners) are more responsible for the resulting genocide than mere participants in the killing.[54] He believes that incitement should be prosecuted more harshly than non-leadership participation for this reason, and because "the crime in question is not merely the individual act of killing or harming, but rather the mass crime of intending to destroy a protected group."[55]

History

Origins

According to Ben Kiernan, Cato the Elder may have made the first recorded incitement to genocide when he repeatedly called for Carthage to be destroyed ("Carthago delenda est").[56] The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a 1903 antisemitic hoax, has been described as a "warrant for genocide". It was influential among the Nazis and also has gained a following in the Islamic world, being referenced in the Hamas Covenant and frequently discussed in the state-controlled Iranian media and by Hezbollah.[57]

Armenian genocide

During the Armenian genocide, Ottoman propaganda described Armenians as "traitors, saboteurs, spies, conspirators, vermin, and infidels". At a meeting of the Committee of Union and Progress in February 1915, a speaker argued that "It is absolutely necessary to eliminate the Armenian people in its entirety, so that there is no further Armenian on this earth and the very concept of Armenia is extinguished." The party "envisioned the Armenian as an invasive infection in Muslim Turkish society", and CUP propagandist Ziya Gökalp promoted the idea that "Turkey could only be revitalized if it rid itself of its non-Muslim elements".[58] This propaganda led directly to the murder of over a million Armenians.[59]

The Holocaust

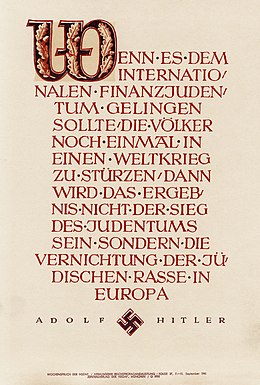

Gordon identifies three strategies that the Nazi leadership employed in order to spread hate propaganda about Jews: statements by Nazi leaders, the Ministry of Propaganda, and destruction of the independent press.[61] American historian Jeffrey Herf has argued that the role of euphemisms in Nazi propaganda has been exaggerated, and in fact Nazi leaders often made direct threats against Jews.[62] The German dictator Adolf Hitler was the most important Nazi propagandist.[61][63] His speeches and statements against the Jews were broadcast on the radio and reprinted on the front pages of the party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter, as well as other major newspapers.[64][63] Goebbels' Ministry of Propaganda achieved "wholesale control of the mass media", and from 4 October 1933, all independent media was required to report to Otto Dietrich's Reich League of the German Press, which fined or censored newspaper editors who failed to follow Nazi ideology.[65]

According to Nazi propaganda, an international Jewish conspiracy controlled the Allies and started World War II to "Bolshevize" the world; Germany fought back with a "war against the Jews".[66] Nazi propagandists repeatedly accused "international Jewry" of plotting the exterminatation (Ausrottung) or annihilation (Vernichtung) of the German people and threatened to do the same to the Jews.[67][68] As evidence, the obscure self-published American book Germany Must Perish!, which advocated the compulsory sterilization of all Germans, was repeatedly emphasized in Nazi propaganda.[69] Hitler's prophecy, found in a 1939 speech which blamed Jews for the war and predicted their annihilation in that event, was frequently quoted during the killings of Jews and was another means of arguing for genocide.[70] Jews inside Europe were presented as a fifth column and saboteurs who posed a serious threat to the German war effort, even as mass deportations to extermination camps were ongoing.[71]

Another tactic used to incite genocide against Jews was to portray them as subhumans (Untermenschen).[72] According to Nazi propaganda, Jews were "parasites, plague, cancer, tumour, bacillus, bloodsucker, blood poisoner, lice, vermin, bedbugs, fleas and racial tuberculosis" on the German national community, which was allegedly threatened by "Jewish disease".[73] Goebbels described Jews as "the lice of civilized humanity". Nazi jurist Walter Buch wrote in the legal journal Deutsche Justiz: "the National Socialist has recognized...[that] the Jew is not a human being".[74] By excluding Jews from humanity, it became justified to kill them.[75]

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and Nazi collaborator Amin al-Husseini has also been described as inciting genocide from 1937.[76] For example, in a 1944 radio address for Bosnian Muslims, he stated, "Kill the Jews wherever you find them. This pleases God, history, and religion."[77] Al-Husseini wanted to extend the Nazi genocide to Muslim-majority areas, as was implemented where German forces were able to reach, in the Caucasus, North Africa, and the Balkans.[78] His ideas have had a substantial influence among radical Arab nationalists and Islamists, and have influenced Hamas, Hezbollah, the Iranian government, the Muslim Brotherhood, and al-Qaida.[79]

Bosnian genocide

In 1991, the state of Yugoslavia (which had consisted of Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, Slovenes, Albanians, Slavic Macedonians, and Montenegrins) broke apart and fell into ethnic violence, which began with the secession of Croatia and Slovenia from the Serbian-led government in Belgrade. Bosnia-Herzegovina, an ethnically divided region with a plurality of Bosniaks as well as large Serbian and Croatian minorities, declared independence in March 1992. Serbs in Bosnia were represented by Serb Democratic Party (SDS), whose leader, Radovan Karadžić, had already threatened Bosniaks with genocide: supporting independence "might lead Bosnia into a hell and [cause] one people to disappear". Serbs did not recognize Bosnian independence and instead started the Bosnian War. Serbian forces committed many war crimes during the conflict, which included ethnic cleansing of non-Serbs, mass rapes, imprisonment in internment camps and the Srebenica massacre.[80]

Alongside the Serb military campaign, there was also a Serb propaganda campaign which aimed to instill "mutual fear and hatred and particularly inciting the Bosnian Serb population against the other ethnicities", according to the judgement in Prosecutor v. Brđanin. Because of the propaganda, people who had lived peacefully together turned against each other and became murderers. In 1991, Wolves of Vučjak and other Serb militia groups helped the SDS seize control of the TV stations, which were subsequently used for pro-Serb propaganda.[81] According to this propaganda, which became more virulent as the war continued, Bosniaks and Croats would commit genocide against the Serbs unless they were eliminated first. The most extreme broadcasts, according to Brđanin, "openly incited people to kill non-Serbs".[82]

Rwandan genocide

Incitement to genocide attracted attention due to its occurrence prior to and during the Rwandan genocide in 1994, in which more than a million Tutsi people were killed.[83][34][84] The pro-genocide media, especially RTLM, was referred to as "radio genocide", "death by radio" and "the soundtrack to genocide", and its causative role was recognized by international commentators.[83] Rwanda, a former Belgian colony, included Hutu (84%) and Tutsi (15%) populations. Under colonial rule, Tutsi were favored to the exclusion of Hutus, leading to a buildup of ethnic resentment. After majority rule began in 1962, Hutus unleashed violence against Tutsis which led many of the latter to flee to neighboring countries. In 1987, these exiles created Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), which invaded Rwanda in 1990.[85] In 1993, international pressure caused the Hutu government under Juvénal Habyarimana to sign the Arusha Accords with the RPF, but Hutu hardliners took to the media to denounce the agreement, Belgium, and Tutsis.[86]

The state-controlled Radio Rwanda was taken over by Hutu extremists for broadcasting hate propaganda.[87] A tabloid newspaper, Kangura, was also responsible for inicitement, juxtaposing a picture of a machete with the question "What shall we do to complete the social revolution of 1959?"[88] At Ferdinand Nahimana's behest, in 1992 Radio Rwanda broadcast a fabricated "hit list" supposedly drawn up by Tutsis as Hutu militias were being bussed to the target area. The militiamen killed hundreds of Tutsi civilians in the Bugesera massacres, which proved to be a "dress rehearsal" for the 100 days of murder that began in April 1994. Also in 1992, Léon Mugesera called for Tutsi to be sent "back to Ethiopia" via the non-navigable Nyabarongo River, which had been previously used to dispose of the bodies of Tutsis murdered in ethnic violence. The Rwandan Minister of Justice soon filed incitement charges against him, causing Mugesera to flee to Canada.[89] After Nahimana was sacked from Radio Rwanda due to his role in the Bugesera massacres, he and others set up a private radio station, RTLM, which played the key role in inciting the genocide. Gordon describes four categories of RTLM broadcasts before the genocide. The first type criticized Tutsis based on alleged characteristics (such as wealth, similar to antisemitism, or physical traits). Another type of broadcast generalized all Tutsis as "inyenzi" (cockroaches) and Inkotanyi, a dangerous feudal warrior. The RTLM also acknowledged its reputation for inciting racial hatred, and denounced specific Tutsis (on 3 April, a doctor in Cyangugu was mentioned in a broadcast; he was murdered on 6 April.)[90]

The genocide began on 6 April 1994 with the assassination of Habyarimana, whose plane was shot down over Kigali. Hutu extremists organized death squads which assassinated Tutsi and moderate Hutu politicians. A unit of Belgian peacekeepers were also murdered, in order to encourage the UN to withdraw its peacekeeping mission.[91]

Islamism

Joseph Spoerl writes that many 20th-century Islamists believe a "Jewish conspiracy to destroy Muslims, the Islamic faith, and Islamic culture", which closely correlates with calls for genocide of Jews.[92] According to Robert Wistrich, Islamist extremist groups believe that there is a war between "Muslims and Jews in which no compromise is possible" and seek an "apocalyptic genocidal resolution of the conflict with the Jews".[93] In 2015, Esther Webman wrote "The alleged eternal enmity of the Jews to Islam is dominant in Islamist thought today, suggesting a justification for genocidal measures against them to free humanity from their evil."[94] The influential Sunni cleric Yusuf al-Qaradawi, accepted as the highest spiritual authority by Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood, once said, referring to an "oppressive, Jewish, Zionist band of people": "kill them, down to the very last one". Al-Qaradawi has also endorsed conspiracy theories accusing Jews of plotting to destroy Islam and take over the entire Middle East.[95]

Hamas

Hamas, an Islamist Palestinian militant group that has controlled the Gaza Strip since 2007, has fired thousands of rockets indiscriminately into Israeli civilian areas and orchestrated a suicide bombing campaign aimed at Israeli civilians.[96][97][98] Hamas has been accused of incitement to genocide by Benjamin Netanyahu's government,[99] the Simon Wiesenthal Center,[100] Daniel Goldhagen,[101] Irwin Cotler,[102] Jeffrey Goldberg, and others, especially due to the contents of the Hamas Charter.[98] The 1988 Hamas Charter quotes the hadith: "The day of judgment will not come until Muslims fight the Jews (killing the Jews), when the Jews will hide behind stones and trees. The stones and trees will say ‘O Muslims, O Abdulla, there is a Jew behind me, come and kill him.'"[98][93] Goldberg described this statement as "a frank and open call for genocide".[98]

Several statements by Hamas officials have been described as incitement to genocide.[103] In 2010, Abdallah Jarbu, a Hamas deputy minister, said, "May He [Allah] annihilate this filthy people [Jews] who have neither religion nor conscience."[104][105][lower-alpha 1] In 2012, the Hamas politician Ahmad Bahar delivered a televised sermon in which he prayed for Allah to kill "the Jews and their supporters... [and] the Americans and their supporters... without leaving a single one".[107] During a 2014 children's broadcast on Al-Aqsa TV, one of the participants says that she wants to "shoot Jews", all of them.[107] During the March of Return protests along the Israel–Gaza barrier in 2019, Hamas official Fathi Hammad asked Palestinians around the world to "go out and slaughter and kill Jews... [Palestinians] must attack every Jew who exists in the globe, slaughter and kill them."[100]

Iran

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran is controlled by an Islamic government.[108] Iran has attempted to develop nuclear weapons and uses proxy terrorism (via Hamas, Hezbollah, and Islamic Jihad) to attack and threaten Israeli civilians.[97][109] Incendiary statements calling for the destruction of Israel are common in Iranian politics.[110] President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has called for Israel to be "wiped Israel off the map"[111] and predicted the destruction of Israel on multiple occasions, stating "the growing turmoil in the Islamic world would in no time wipe Israel away" and that Israel "will one day vanish," "will be gone, definitely," and that Israeli Jews "are nearing the last days of their lives".[112][35] He once asked an audience a rhetorical question: were Israeli Jews human beings? He answered in the negative: "'They are like cattle, nay, more misguided.' A bunch of bloodthirsty barbarians. Next to them, all the criminals of the world seem righteous." He also called Israelis "filthy bacteria" and "wild beast".[36][113] Other Iranian politicians have made similar statements.[110]

Gregory Stanton, Gregory Gordon, and other legal scholars contend that Ahmadinejad is guilty of incitement to genocide,[50][111] although Benesch disagrees.[111][114] Paul Martin, Prime Minister of Canada, said "This threat to Israel's existence, this call for genocide coupled with Iran's obvious nuclear ambitions is a matter that the world cannot ignore."[115] In December 2006, the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations and the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs hosted a symposium "Bring Ahmadinejad to Justice For Incitement to Genocide". The resulting petition, authored by Irwin Colter, has been signed by Elie Wiesel, Former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Louise Arbour, and the former Swedish Deputy Prime Minister Per Ahlmark, and historian Yehuda Bauer.[116][117] Former diplomats John Bolton and Dore Gold, as well as Alan Dershowitz and other experts from the United States, Canada, and Israel, attempted to bring prosecution against Ahmadinejad for incitement to genocide in the International Court of Justice.[118] In 2007, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution calling on Ahmadinejad to be investigated for inciting genocide.[111][117] In 2012, Canada severed diplomatic relations with Iran; incitement to genocide was cited in the foreign ministry's statement.[119]

Islamic State

The Islamic State (IS) has incited genocide against Yazidi people by dehumanizing them as "Satanists" and "devil worshippers" and issuing fatwas which recommend the sexual slavery of Yazidi women.[120] According to IS propaganda, Yazidis' "continual existence to this day is a matter that Muslims should question as they will be asked about it on Judgement Day."[121] Mohamed Elewa Badar argues IS has incited genocide, not just against Yazidis but against all those deemed kafir (infidels) in their extremist interpretation of Islam.[122] IS advocates the "partial or total eradication of non-Muslim groups",[123] and has committed genocide against the Yazidis.[124]

International treaties

Based on the precedent of Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher, who was convicted of crimes against humanity by the International Military Tribunal in 1946, "[d]irect and public incitement to commit genocide" was forbidden by the Genocide Convention (1948), Article 3.[3] During the debate on the convention, the Soviet delegate argued that "[i]t was impossible that hundreds of thousands of people should commit so many crimes unless they had been incited to do so" and that inciters, "the ones really responsible for the atrocities committed", ought to face justice.[125] Several delegates supported a provision that would criminalize hate propaganda even if it did not directly call for violence. The Secretariat Draft called for the criminalization of "[a]ll forms of public propaganda tending by their systematic and hateful character to provoke genocide, or tending to make it appear as a necessary, legitimate or excusable act".[126] However, the United States was reluctant to criminalize genocide incitement due to concerns over freedom of the press,[127] and opposed any provisions that were seen as overly broad and likely to infringe on freedom of speech.[128]

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965) prohibits "all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred, incitement to racial discrimination, as well as all acts of violence or incitement to such acts against any race or group of persons of another colour or ethnic origin".[127] One of the most widely ratified treaties, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) also prohibits "propaganda for war" and "advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence" (which arguably conflicts with a separate article calling for freedom of speech).[129] However, according to Wilson, many countries signed these treaties to maintain a façade of respect for human rights while violating their provisions and there is little effective international enforcement of human rights outside of the European Court of Human Rights. No more trials for incitement to genocide were held until nearly fifty years after the ratification of the Genocide Convention.[130]

Since 1998, incitement to genocide is also forbidden by Article 25(3)(e) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[131][3] According to the Rome Statue, incitement is not "a crime in its own right" and an inchoate offense, as it was considered in previous prosecutions, but simply one possible "mode of criminal participation in genocide". Thomas Davies contends that this change makes it less likely that a perpetrator will be held accountable for incitement.[132]

Case law

Nuremberg trials

Julius Streicher, the founder, editor, and publisher of Der Stürmer, was found responsible for antisemitic articles referring to Jews as "a parasite, an enemy, and an evil-doer, a disseminator of diseases" or "swarms of locusts which must be exterminated completely".[133] He continued to publish antisemitic articles even after learning of the mass murder of Jews in the occupied Soviet Union.[33] The prosecution argued that "Streicher helped to create, through his propaganda, the psychological basis necessary for carrying through a program of persecution which culminated in the murder of six million men, women, and children."[134] Because Streicher's articles "incited the German people to active persecution" and "murder and extermination", he was convicted of crimes against humanity by the IMT in 1946.[133]

Hans Fritzsche was the Chief of the German Press Division of Joseph Goebbels' Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda from 1938; in this position he issued instructions to German newspapers telling them what to report.[135] According to the IMT prosecution, he "incited and encouraged the commission of War Crimes by deliberately falsifying news to arouse in the German People those passions which led them to the commission of atrocities". Fritzsche was acquitted because the court was "not prepared to hold that [his broadcasts] were intended to incite the German people to commit atrocities on conquered peoples".[136] Nuremberg prosecutor Alexander Hardy later said that evidence not available to the prosecution at the time proved Fritzsche not only knew of the extermination of European Jews but also "played an important part in bringing [Nazi crimes] about", and would have resulted in his conviction.[137] Fritzsche was later classified as Group I (Major Offenders) by a denazification court which gave him the maximum penalty, eight years' imprisonment.[137][138]

Otto Dietrich was not tried at the main Nuremberg trial, but was convicted of crimes against humanity at the Ministries Trial, one of the subsequent Nuremberg trials.[139] According to Hardy, Dietrich "more than anyone else, was responsible for presenting to the German people the justification for liquidating the Jews".[140] Hardy noted that Dietrich not only controlled Der Stürmer but another 3,000 newspapers and 4,000 periodicals with a combined circulation over 30 million.[140] The judgement against him noted that he conducted "a well thought-out, oft-repeated, persistent campaign to arouse the hatred of the German people against Jews" despite the lack of direct calls for violence made by him.[141]

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

The ICTR indicted three people for incitement to genocide in the so-called Rwanda Media Case: Hassan Ngeze, Ferdinand Nahimana, and Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza. All were convicted. The judges asserted that "The power of the media to create and destroy fundamental human values comes with great responsibility. Those who control such media are accountable for its consequences". They noted that "Without a firearm, machete or any physical weapon, you caused the deaths of thousands of innocent civilians". Prosecutors were able to prove that "direct" calls to genocide were made despite the use of euphemisms such as "go to work" for murdering Tutsi. After an appeal, the conviction of Barayagwiza was vacated because he had not been in control of the media while the genocide was occurring. However, Barayagwiza was still guilty of "instigating the perpetration of acts of genocide" and crimes against humanity.[3][24]

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia

The ICTY has focused on prosecuting crimes other than genocide, because it is believed that the hate speech that occurred during the Bosnian genocide did not meet the legal standard of incitement to genocide.[3] Serb politician Vojislav Šešelj was indicted for crimes against humanity, including "war propaganda and incitement of hatred towards non-Serb people".[142] Serbian politician Radovan Karadžić was convicted of "participating in a joint criminal enterprise to commit crimes against humanity on the basis of his public speeches and broadcasts".[143] Dario Kordić and Radoslav Brđanin were also convicted of crimes based on instigating violence in public speeches.[143]

National case law

In 2016, Léon Mugesera was convicted of incitement to genocide and inciting ethnic hatred by a Rwandan court based on his 1992 speech.[144]

Countering incitement

Inclusion of incitement in the Genocide Convention was intended to prevent genocide.[145] As the judgement of Prosecutor v. Kalimanzira stated, "The inchoate nature of the crime allows intervention at an earlier stage, with the goal of preventing the occurrence of genocidal acts."[146] Irwin Cotler stated that efforts to enforce the Genocide Convention in inchoate incitement cases "have proven manifestly inadequate".[147] Alternately, prosecution for incitement after the genocide had concluded could have deterrent effect on those planning to commit the crime, but the effectiveness of international criminal trials as a deterrent is disputed.[148] However, deterrence is less effective when the definition of the crime is contested and undefined.[20]

Besides prosecutions, non-judicial interventions (called "information intervention") is possible against incitement, such as jamming broadcasting frequencies used to disseminate incitement or broadcasting counterspeech advocating against genocide.[149] Genocide-inciting social media accounts and websites (such as those used by Islamic State to spread propaganda) can be shut down and taken offline. However, propagandists can circumvent these methods by creating new accounts or moving to a different hosting service.[150] As an alternative to outright censorship, Google developed a "Redirect Method" which identifies individuals searching for IS-related material and redirects them to content which challenges IS narratives.[151]

See also

Notes

- "[The Jews] suffer from a mental disorder, because they are thieves and aggressors.… They want to present themselves to the world as if they have rights, but in fact, they are foreign bacteria – a microbe unparalleled in the world. It’s not me who says this. The Koran itself says they have no parallel: “You shall find the strongest men in enmity to the believers to be the Jews.” May He [Allah] annihilate this filthy people who have neither religion nor conscience. I condemn whoever believes in normalizing relations with them, whoever supports sitting down with them, and whoever believes they are human beings. They are not human beings. They are not people. They have no religion, no conscience, and no moral values."[104][106]

References

- Gordon 2017, p. 118.

- Schabas 2018, pp. 17–18.

- "Incitement to Genocide in International Law". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Benesch 2008, p. 493.

- Wilson 2017, p. 66.

- Gordon 2017, p. 399.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 307, Chapter 8 passim.

- Gordon 2017, p. 190.

- Gordon 2017, p. 191.

- May 2010, p. 101.

- Timmermann 2006, p. 823.

- Wilson 2017, p. 25.

- Gordon 2008, pp. 906–907.

- Wilson 2017, p. 36.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 398–399.

- Benesch 2008, p. 497.

- Davies 2009, pp. 245–246.

- Benesch 2008, pp. 486–487.

- Mugesera v. Canada

- Gordon 2017, p. 216.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 320, 402.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 274–275.

- Benesch 2008, pp. 494–495.

- Wilson 2017, p. 2.

- Gordon 2017, p. 274.

- Gordon 2017, p. 277.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 277–278.

- Gordon 2017, p. 281.

- Gordon 2017, p. 400.

- Benesch 2008, p. 503.

- Gordon 2017, p. 284.

- Gordon 2017, p. 285.

- Benesch 2008, p. 510.

- Timmermann 2006, p. 824.

- Gordon 2017, p. 286.

- Gordon 2017, p. 287.

- Blum et al. 2008, p. 204.

- Haslam 2019, pp. 119–120.

- Haslam 2019, p. 134.

- Benesch 2008, p. 504.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 287–288.

- Marcus 2012, pp. 357–358.

- Benesch 2008, p. 506.

- Marcus 2012, pp. 359–360.

- Marcus 2012, pp. 360–361.

- Gordon 2017, p. 289.

- Herf 2005, p. 55.

- Gordon 2017, p. 290.

- Gordon 2017, p. 291.

- Ginsburg, Mitch (18 September 2012). "Genocides, unlike hurricanes, are predictable, says world expert. And Iran is following the pattern". Times of Israel. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Benesch 2008, p. 499.

- Benesch 2008, p. 500.

- May 2010, p. 119.

- May 2010, p. 123.

- May 2010, pp. 151–152.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 31–32.

- Spoerl 2020, pp. 212, 216, 223, 224.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 34–35.

- Gordon 2017, p. 36.

- Herf 2006, p. 52.

- Gordon 2017, p. 37.

- Herf 2005, p. 54.

- Bytwerk 2005, p. 48.

- Herf 2005, p. 56.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 38–39, 114–115.

- Herf 2005, p. 63.

- Herf 2005, pp. 55–56.

- Bytwerk 2005, p. 39.

- Bytwerk 2005, pp. 42, 46.

- Bytwerk 2005, pp. 48–49.

- Gordon 2017, p. 40.

- Gordon 2017, p. 39.

- Blum et al. 2008, p. 205.

- Benesch 2008, pp. 503–504.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 39–40.

- Rubin & Schwanitz 2014, p. 94.

- Spoerl 2020, p. 214.

- Rubin & Schwanitz 2014, p. 123.

- Rubin & Schwanitz 2014, p. 95.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 41–42.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 42–43.

- Gordon 2017, p. 44.

- Wilson 2017, p. 1.

- Gordon 2017, p. 46.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 46–47.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 49–50.

- Gordon 2017, p. 50.

- Gordon 2017, p. 51.

- Gordon 2017, p. 52.

- Gordon 2017, p. 53.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 53–54.

- Spoerl 2020, p. 212.

- Wistrich 2014, p. 36.

- Spoerl 2020, p. 225.

- Spoerl 2020, pp. 221, 236.

- Gordon 2008, p. 862.

- Gordon 2014, pp. 600–601.

- Goldberg, Jeffrey (4 August 2014). "What Would Hamas Do If It Could Do Whatever It Wanted?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Ahren, Raphael; Lieber, Dov (1 May 2017). "Israel dismisses purportedly 'friendlier' Hamas principles". Times of Israel. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "'A Fatwa for Genocide' – Wiesenthal center slams Hamas charter". The Jerusalem Post. 14 July 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Goldhagen 2009, p. 498.

- Eltis 2008, p. 464.

- Spoerl 2020, pp. 218–220.

- Spoerl 2020, p. 220.

- Goldhagen 2009, pp. 292–293.

- Goldhagen 2009, p. 292.

- Spoerl 2020, p. 219.

- Gordon 2008, p. 858.

- Gordon 2008, pp. 861, 911, 919.

- Gordon 2014, p. 600.

- Gordon 2008, p. 855.

- Gordon 2008, p. 866.

- Spoerl 2020, p. 222.

- Benesch 2008, pp. 490–491.

- "Canada slams Iran's anti-Israel statement". Ynetnews. 14 November 2005. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Cotler 2009, p. i.

- Benesch 2008, p. 490.

- Tait, Robert; Pilkington, Ed (13 December 2006). "Move to bring genocide case against Ahmadinejad as Iran president repeats call to wipe out Israel". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Canada Closes Embassy in Iran, Expels Iranian Diplomats from Canada". Iran Watch. 7 September 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Gordon 2017, p. 59.

- Cheterian 2019, p. 7.

- Badar 2016, p. 410.

- Richter et al. 2018, p. 4.

- Cheterian 2019, p. 12.

- Timmermann 2006, p. 852.

- Timmermann 2014, p. 154.

- Wilson 2017, p. 3.

- Timmermann 2014, p. 155.

- Wilson 2017, pp. 3–4.

- Wilson 2017, p. 4.

- Davies 2009, p. 245.

- Davies 2009, pp. 245, 260.

- Timmermann 2006, pp. 827–828.

- Gordon 2017, p. 328.

- Gordon 2014, p. 578.

- Timmermann 2006, p. 828.

- Gordon 2014, p. 579.

- Timmermann 2006, p. 829.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 114–115.

- Gordon 2017, p. 115.

- Gordon 2017, pp. 330–331.

- Benesch 2008, p. 511.

- Wilson 2017, p. 5.

- Gordon 2017, p. 398.

- Schabas 2018, p. 18.

- Gordon 2017, p. 215.

- Gordon 2017, p. 217.

- Benesch 2008, pp. 497–498.

- Benesch 2008, p. 488.

- Richter et al. 2018, p. 15.

- Richter et al. 2018, p. 16.

Sources

- Badar, Mohamed Elewa (2016). "The Road to Genocide: The Propaganda Machine of the Self-declared Islamic State (IS)". International Criminal Law Review. 16 (3): 361–411. doi:10.1163/15718123-01603004.

- Benesch, Susan (2008). "Vile Crime or Inalienable Right: Defining Incitement to Genocide". Virginia Journal of International Law. 48 (3). SSRN 1121926.

- Blum, Rony; Stanton, Gregory H.; Sagi, Shira; Richter, Elihu D. (2008). "'Ethnic cleansing' bleaches the atrocities of genocide". European Journal of Public Health. 18 (2): 204–209. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckm011. ISSN 1101-1262. PMID 17513346.

- Bytwerk, Randall L. (2005). "The Argument for Genocide in Nazi Propaganda". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 91 (1): 37–62. doi:10.1080/00335630500157516.

- Cotler, Irwin (2009). "The Danger of a Nuclear, Genocidal and Rights-Violating Iran:The Responsibility to Prevent Petition" (PDF).

- Cheterian, Vicken (2019). "ISIS genocide against the Yazidis and mass violence in the Middle East". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies: 1–13. doi:10.1080/13530194.2019.1683718.

- Davies, Thomas E. (2009). "How the Rome Statute Weakens the International Prohibition on Incitement to Genocide" (PDF). Harvard Human Rights Journal. 22 (2): 245–270.

- Eltis, Karen (2008). "A constitutional "right" to deny and promote genocide? Preempting the usurpation of human rights discourse towards incitement from a Canadian perspective" (PDF). Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution. 9: 463–478.

- Haslam, Nick (2019). "The Many Roles of Dehumanization in Genocide". In Newman, Leonard S. (ed.). Confronting Humanity at Its Worst: Social Psychological Perspectives on Genocide. Oxford University Press. pp. 119–138. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190685942.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-19-068594-2.

- Herf, Jeffrey (2005). "The "Jewish War": Goebbels and the Antisemitic Campaigns of the Nazi Propaganda Ministry". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 19 (1): 51–80. doi:10.1093/hgs/dci003.

- Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah (2009). Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-0-7867-4656-9.

- Gordon, Gregory (2008). "From Incitement to Indictment - Prosecuting Iran's President for Advocating Israel's Destruction and Piecing Together Incitement Law's Emerging Analytical Framework". Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 98 (3): 853–920. ISSN 0091-4169. JSTOR 40042789.}

- Gordon, Gregory S. (2014). "The Forgotten Nuremberg Hate Speech Case: Otto Dietrich and the Future of Persecution Law". Ohio State Law Journal. 75: 571–607. SSRN 2457641.

- Gordon, Gregory S. (2017). Atrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-061270-2.

- Marcus, Kenneth L. (2012). "Accusation in a Mirror". Loyola University Chicago Law Journal. 43 (2): 357–393. SSRN 2020327.

- May, Larry (2010). Genocide: A Normative Account. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48426-8.

- Richter, Elihu D.; Markus, Dror Kris; Tait, Casey (2018). "Incitement, genocide, genocidal terror, and the upstream role of indoctrination: can epidemiologic models predict and prevent?". Public Health Reviews. 39 (1): 30. doi:10.1186/s40985-018-0106-7. PMC 6196410. PMID 30377548.

- Rubin, Barry; Schwanitz, Wolfgang G. (2014). Nazis, Islamists, and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19932-1.

- Schabas, William A. (2018). "Prevention of Crimes Against Humanity". Journal of International Criminal Justice. 0: 1–24. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqy033.

- Spoerl, Joseph S. (2020). "Parallels between Nazi and Islamist Anti-Semitism". Jewish Political Studies Review. 31 (1/2): 210–244. ISSN 0792-335X. JSTOR 26870795.

- Timmermann, Wibke Kristin (2006). "Incitement in international criminal law" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 88 (864): 823–852.

- Timmermann, Wibke Kristin (2014). Incitement in International Law. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-66966-1.

- Wilson, Richard Ashby (2017). Incitement on Trial: Prosecuting International Speech Crimes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-10310-8.

- Wistrich, Robert S. (2014). "Gaza, Hamas, and the Return of Antisemitism". Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. 8 (3): 35–48. doi:10.1080/23739770.2014.11446601.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Incitement to genocide |

- Incitement to genocide case law—Case Law Database

- "'Incitement on Trial: Prosecuting International Speech Crimes: A Conversation with Richard Ashby Wilson, Linda Lakhdhir, Marko Milanovic and Nadine Strossen" (November 8, 2017) Open Society Foundations

- Richter, Elihu D.; Barnea, Alex (Summer 2009). "Tehran's Genocidal Incitement Against Israel". Middle East Quarterly. 16 (3): 45–51. A list of Iranian statements that could be considered incitement to genocide.

- Weiner, Justus Reid (January 2007). "Referral of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and the Member State of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations, Including Its Main Bodies, Judicial Organs, and Specialized Agencies on the Charge of Incitement to Commit Genocide and Other Charges" (PDF). International Journal of Punishment and Sentencing. 3 (1): 1–40. ISBN 965-218-055-6. Gale Document Number: GALE A189952092.