1971 Bangladesh genocide

The genocide in Bangladesh began on 26 March 1971 with the launch of Operation Searchlight,[5] as West Pakistan (now Pakistan) began a military crackdown on the Eastern wing (now Bangladesh) of the nation to suppress Bengali calls for self-determination.[6] During the nine-month-long Bangladesh War for Liberation, members of the Pakistani military and supporting Islamist militias from Jamaat-e-Islami[7] killed between 300,000 and 3,000,000[4][8] people and raped between 200,000 and 400,000 Bengali women,[8][9] according to Bangladeshi and Indian sources,[10] in a systematic campaign of genocidal rape.[11][12] The actions against women were supported by Jamaat-e-Islami religious leaders, who declared that Bengali women were gonimoter maal (Bengali for "public property").[13] As a result of the conflict, a further eight to ten million people, mostly Hindus,[14] fled the country to seek refuge in neighbouring India. It is estimated that up to 30 million civilians were internally displaced[8] out of 70 million.[15] During the war, there was also ethnic violence between Bengalis and Urdu-speaking Biharis.[16] Biharis faced reprisals from Bengali mobs and militias[17] and from 1,000[18] to 150,000[19][20] were killed. Other sources claim it was up to 500,000.[21][22]

| 1971 Bangladesh genocide | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Bangladesh Liberation War | |

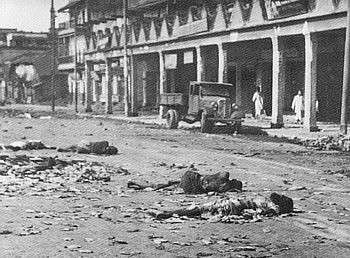

Rayerbazar killing field photographed immediately after the war started, showing bodies of Bengali nationalist intellectuals (Image courtesy: Rashid Talukdar, 1971) | |

| Location | East Pakistan |

| Date | 21 March – 16 December 1971 (8 months, 2 weeks and 3 days) |

| Target | Bengalis |

Attack type | Deportation, ethnic cleansing, mass murder, genocidal rape |

| Deaths | Estimated between 300,000[1] to 3,000,000[2][3][4] |

| Perpetrators | |

| Motive | Anti-Bengali sentiment, anti-Hindu sentiment |

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

| Issues |

| Genocide of indigenous peoples |

|

| Late Ottoman genocides |

| World War II (1941–1945) |

| Cold War |

|

| Genocides in postcolonial Africa |

|

| Ethno-religious genocide in contemporary era |

|

| Related topics |

| Category |

| Part of a series on |

| Persecution of Bengali Hindus |

|---|

Part of Bengali Hindu history |

| Discrimination |

| Persecution |

|

| Opposition |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Bangladesh |

|

|

|

Ancient

|

|

Classical

|

|

Medieval

|

|

Modern

|

|

Contemporary

|

|

Related articles |

|

|

There is an academic consensus that the events which took place during the Bangladesh Liberation War constituted a genocide,[23] and warrant judicial accountability.[24] However, some scholars deny it was a genocide.[25]

Background

Following the partition of India, the new state of Pakistan represented a geographical anomaly, with two wings separated by 1,600 kilometres (1,000 mi) of Indian territory.[26] The wings were not only separated geographically, but also culturally. The authorities of the West viewed the Bengali Muslims in the East as "too Bengali" and their application of Islam as "inferior and impure", believing this made the Bengalis unreliable "co-religionists". To this extent politicians in West Pakistan began a strategy to forcibly assimilate the Bengalis culturally.[27]

The Bengali people were the demographic majority in Pakistan, making up an estimated 75 million in East Pakistan, compared with 55 million in the predominantly Punjabi-speaking West Pakistan.[28] The majority in the East were Muslim, with large minorities of Hindus, Buddhists and Christians. The West considered the people of the East to be second-class citizens, and Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi, who served as head of the Pakistani Forces in East Pakistan in 1971, referred to the region as a "low-lying land of low-lying people".[29]

In 1948, a few months after the creation of Pakistan, Governor-General Mohammad Ali Jinnah declared Urdu as the national language of the newly formed state,[30] although only four per cent of Pakistan's population spoke Urdu at that time.[31] He branded those who supported the use of Bengali as communists, traitors and enemies of the state.[32] The refusal by successive governments to recognise Bengali as the second national language culminated in the Bengali language movement and strengthened support for the newly formed Awami League, which was founded in the East as an alternative to the ruling Muslim League.[33] A 1952 protest in Dhaka, the capital of East Pakistan, was forcibly broken up, resulting in the deaths of several protesters. Bengali nationalists viewed those who had died as martyrs for their cause, and the violence led to calls for secession.[34] The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 caused further grievances, as the military had assigned no extra units to the defence of the East.[35] This was a matter of concern to the Bengalis who saw their nation undefended in case of Indian attack during the conflict of 1965,[36][37] and that Ayub Khan, the dictator-ruler of Pakistan, was willing to lose the East if it meant gaining Kashmir.[38]

The slow response to the Bhola cyclone which struck on 12 November 1970 is widely seen as a contributing factor in the December 1970 general election. The East Pakistan-based Awami League, headed by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won a national majority in the first democratic election since the creation of Pakistan, sweeping East Pakistan. But, the West Pakistani establishment prevented them from forming a government.[39] President Yahya Khan, encouraged by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto,[40] banned the Awami League and declared martial law.[41] The Pakistani Army demolished Ramna Kali Mandir (temple) and killed 85 Hindus.[42] On 22 February 1971, General Yahya Khan is reported to have said "Kill three million of them, and the rest will eat out of our hands."[43][44][45]

Some Bengalis supported a united Pakistan and opposed secession from it.[46] According to Indian academic Sarmila Bose, these pro-Pakistan Bengalis constituted a significant minority, and included the Islamic parties. Moreover, many Awami League voters who hoped to achieve provincial autonomy may not have desired secession.[47] Additionally, some Bengali officers and soldiers remained loyal to the Pakistani Army and were taken as prisoners of war by India along with other West Pakistani soldiers.[48] Thus, according to Sarmila Bose, there were many pro-regime Bengalis who killed and persecuted the pro-liberation fighters.[48] Sydney Schanberg reported the formation of armed civilian units by the Pakistani Army in June 1971. Only a minority of the recruits were Bengali while most were Biharis and Urdu speakers. The units with local knowledge played an important role in the implementation of the Pakistani Army's genocide.[49] American writer Gary J. Bass believes that the breakup of Pakistan was not inevitable, identifying 25 March 1971 as the point where the idea of a united Pakistan ended for Bengalis with the start of military operations.[50] According to John H. Gill, since there was widespread polarisation between pro-Pakistan Bengalis and pro-liberation Bengalis during the war, those internal battles are still playing out in the domestic politics of modern-day Bangladesh.[51]

Operation Searchlight

Operation Searchlight was a planned military operation carried out by the Pakistani Army to curb elements of the separatist Bengali nationalist movement in East Pakistan in March 1971.[52] The Pakistani state justified commencing Operation Searchlight on the basis of anti-Bihari violence by Bengalis in early March.[53] Ordered by the government in West Pakistan, this was seen as the sequel to Operation Blitz which had been launched in November 1970. On 1 March 1971 East Pakistan governor Admiral Syed Mohammed Ahsan was replaced after disagreeing with military action in East Pakistan.[54][55] His successor Sahibzada Yaqub Khan resigned after refusing to use soldiers to quell a mutiny and disagreement with military action in East Pakistan.[56][57]

According to Indian academic[58][59] Sarmila Bose, the postponement of the National Assembly on 1 March led to widespread lawlessness spread by Bengali protesters during the period of 1–25 March, in which the Pakistani government lost control over much of the province. Bose asserts that during this 25-day period of lawlessness, attacks by Bengalis on non-Bengalis were common as well as attacks by Bengalis on Pakistani military personnel who, according to Bose and Anthony Mascarenhas, showed great restraint until 25 March, when Operation Searchlight began.[60] Bose also described the atrocities committed by the Pakistani Army in her book.[61] According to Anthony Mascarenhas, the actions of the Pakistani Army compared to the violence by Bengalis was "altogether worse and on a grander scale".[1]

On the night of 25 March 1971 the Pakistani Army launched Operation Searchlight. Time magazine dubbed General Tikka Khan, the "Butcher of Bengal" for his role in operation Searchlight.[62] Targets of the operation included Jagannath Hall which was a dormitory for non-Muslim students of Dhaka University, Rajarbagh Police Lines, Pilkhana, which is the headquarters of East Pakistan Rifles. About 34 students were killed in the dormitories of Dhaka University. Neighbourhoods of old Dhaka which had a majority Hindu population were also attacked. Robert Payne, an American journalist, estimated that 7,000 people had been killed and 3,000 arrested in that night.[63] Teachers of Dhaka University were killed in the operation by the Pakistani Army.[64] Sheikh Mujib was arrested by the Pakistani Army on 25 March.[65] Ramna Kali Mandir was demolished by the Pakistani Army in March 1971.[66]

The original plan envisioned taking control of the major cities on 26 March 1971, and then eliminating all opposition, political, or military,[67] within one month. The prolonged Bengali resistance was not anticipated by Pakistani planners.[68] The main phase of Operation Searchlight ended with the fall of the last major town in Bengali hands in mid May. The countryside still remained almost evenly contested.[69]

The first report of the Bangladesh genocide was published by West Pakistani journalist Anthony Mascarenhas in The Sunday Times, London on 13 June 1971 titled "Genocide". He wrote: "I saw Hindus, hunted from village to village and door to door, shot off-hand after a cursory 'short-arm inspection' showed they were uncircumcised. I have heard the screams of men bludgeoned to death in the compound of the Circuit House (civil administrative headquarters) in Comilla. I have seen truckloads of other human targets and those who had the humanity to try to help them hauled off 'for disposal' under the cover of darkness and curfew."[70] This article helped turn world opinion against Pakistan and decisively encouraged the Government of India to intervene.[1] On 2 August 1971, Time magazine correspondent sent a dispatch that provided detailed description of the destruction in East Pakistan. It wrote that cities have whole sections damaged from shelling and aerial bombardments. The dispatch wrote: "In Dhaka, where soldiers set sections of the Old City ablaze with flamethrowers and then machine-gunned thousands as they tried to escape the cordon of fire, nearly 25 blocks have been bulldozed clear, leaving open areas set incongruously amid jam-packed slums." It quoted a senior US official as saying "It is the most incredible, calculated thing since the days of the Nazis in Poland."[71][72]

Archer K. Blood, American diplomat wrote in the Blood Telegram: "with support of the Pak military, non-Bengali Muslims are systematically attacking poor people's quarters and murdering Bengalis and Hindus."[73][74]

Estimated killed

.jpg)

Bangladeshi authorities claim that as many as 3 million people were killed, although the Hamoodur Rahman Commission, the official Pakistani government investigation, claimed the figure was only 26,000 civilian casualties.[75][76] The figure of 3 million has become embedded in Bangladeshi culture and literature.[24] Sayyid A. Karim, Bangladesh's first foreign secretary alleges that the source of the figure was Pravda, the news-arm of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[24] Independent researchers have estimated the death toll to be around 300,000 to 500,000 people while others estimate the casualty figure to be 3 million.[8][1][77][78] The United States intelligence agency, the CIA and the State Department estimated that 200,000 people had been killed in the genocide.[79]

According to Sarmila Bose's controversial book Dead Reckoning: Memories of the 1971 Bangladesh War, the number lies somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000.[80][81] However, her book was the subject of strong criticism by journalists; writer and visual artist Naeem Mohaiemen; Nayanika Mookherjee, an anthropologist at Durham University; and others.[80][82][83][84]

In 1976 the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh undertook a comprehensive population survey in Matlab, Noakhali where a total of 868 excess wartime deaths were recorded; this led to an estimated overall excess number of deaths in the whole of Bangladesh of nearly 500,000.[24] Based on this study, the British Medical Journal in 2008, conducted a study by Ziad Obermeyer, Christopher J. L. Murray, and Emmanuela Gakidou which estimated that 125,000–505,000 civilians died as a result of the conflict;[24] the authors note that this is far higher than a previous estimate of 58,000 by Uppsala University and the Peace Research Institute, Oslo.[85] This figure is supported by the statements of Bangladeshi author Ahmed Sharif in 1996, who added that "they kept the truth hidden for getting political advantages".[86] American political scientists Richard Sisson and Leo E. Rose give a low-end estimate of 300,000 dead, killed by all parties, and they deny that a genocide occurred, while American political scientist R. J. Rummel estimated that about 1.5 million people were killed in Bangladesh.[87] Indian journalist Nirmal Sen claims that the total number killed was about 250,000 and among them, about 100,000 were Bengalis and the rest were Biharis.[86]

Many of those killed were the victims of radical religious paramilitary militias formed by the West Pakistani Army, including the Razakars, Al-Shams and Al-Badr forces.[88][89] There are many mass graves in Bangladesh,[90][91] and more are continually being discovered (such as one in an old well near a mosque in Dhaka, located in the Mirpur region of the city, which was discovered in August 1999).[92] The first night of war on Bengalis, which is documented in telegrams from the American Consulate in Dhaka to the United States State Department, saw indiscriminate killings of students of Dhaka University and other civilians.[93]

On 16 December 2002, the George Washington University's National Security Archive published a collection of declassified documents, consisting mostly of communications between US embassy officials and USIS centres in Dhaka and India, and officials in Washington, D.C.[93] These documents show that US officials working in diplomatic institutions within Bangladesh used the terms selective genocide[94][95] and genocide (see Blood telegram) to describe events they had knowledge of at the time. The complete chronology of events as reported to the Nixon administration can be found on the Department of State website.[96]

Islamist militias

The Jamaat-e-Islami[97] as well as other Islamists opposed the Bangladeshi independence struggle and sided with the Pakistani state and armed forces out of Islamic solidarity.[98][99] According to political scientist Peter Tomsen, Pakistan's secret service, in conjunction with the political party Jamaat-e-Islami, formed militias such as Al-Badr ("the moon") and the Al-Shams ("the sun") to conduct operations against the nationalist movement.[100][101] These militias targeted noncombatants and committed rapes as well as other crimes.[16] Local collaborators known as Razakars also took part in the atrocities. The term has since become a pejorative akin to the western term "Judas".[102]

Members of the Muslim League, Nizam-e-Islam, Jamaat-e-Islami and Jamiat Ulema Pakistan, who had lost the election, collaborated with the military and acted as an intelligence organisation for them.[103] Jamaat-e-Islami members and some of its leaders collaborated with the Pakistani forces in rapes and targeted killings.[104] The atrocities by Al-Badr and the Al-Shams garnered worldwide attention from news agencies; accounts of massacres and rapes were widely reported.[101]

Killing of intellectuals

During the war, the Pakistani Army and its local collaborators, mainly Jamaat e Islami carried out a systematic execution of the leading Bengali intellectuals. A number of professors from Dhaka University were killed during the first few days of the war.[105][106] However, the most extreme cases of targeted killing of intellectuals took place during the last few days of the war. Professors, journalists, doctors, artists, engineers and writers were rounded up by the Pakistani Army and the Razakar militia in Dhaka, blindfolded, taken to torture cells in Mirpur, Mohammadpur, Nakhalpara, Rajarbagh and other locations in different sections of the city to be executed en masse, most notably at Rayerbazar and Mirpur.[107][108][109][110] Allegedly, the Pakistani Army and its paramilitary arm, the Al-Badr and Al-Shams forces created a list of doctors, teachers, poets, and scholars.[111][112]

During the nine-month duration of the war, the Pakistani Army, with the assistance of local collaborators systematically executed an estimated 991 teachers, 13 journalists, 49 physicians, 42 lawyers, and 16 writers, artists and engineers.[109] Even after the official ending of the war on 16 December there were reports of killings being committed by either the armed Pakistani soldiers or by their collaborators. In one such incident, notable filmmaker Jahir Raihan was killed on 30 January 1972 in Mirpur allegedly by the armed Beharis. In memory of the people who were killed, 14 December is observed in Bangladesh as Shaheed Buddhijibi Dibosh ("Day of the Martyred Intellectuals").[89][109][113]

Notable intellectuals who were killed from the time period of 25 March to 16 December 1971 in different parts of the country include Dhaka University professors Dr. Govinda Chandra Dev (philosophy), Dr. Munier Chowdhury (Bengali literature), Dr. Mufazzal Haider Chaudhury (Bengali Literature), Dr. Anwar Pasha (Bengali Literature), Dr M Abul Khair (history), Dr. Jyotirmoy Guhathakurta (English literature), Humayun Kabir (English literature), Rashidul Hasan (English literature), Ghyasuddin Ahmed, Sirajul Haque Khan, Faizul Mahi, Dr Santosh Chandra Bhattacharyya[114] and Saidul Hassan (physics), Rajshahi University professors Dr. Hobibur Rahman (mathematics), Prof Sukhranjan Somaddar (Sanskrit), Prof Mir Abdul Quaiyum (psychology) as well as Dr. Mohammed Fazle Rabbee (cardiologist), Dr. AFM Alim Chowdhury (ophthalmologist), Shahidullah Kaiser (journalist), Nizamuddin Ahmed (journalist),[115] Selina Parvin (journalist), Altaf Mahmud (lyricist and musician), Dhirendranath Datta (politician), Jahir Raihan (novelist, journalist, film director) and Ranadaprasad Saha (philanthropist).[116][117]

Violence against women

The generally accepted figure for the mass rapes during the nine-month long conflict is between 200,000 and 400,000.[118][8][119][120] During the war, a fatwa in Pakistan declared that the Bengali freedom fighters were Hindus and that their women could be taken as the 'booty of war'.[121] Imams and Muslim religious leaders publicly declared that the Bengali women were 'gonimoter maal' (war booty) and thus they openly supported the rape of Bengali women by the Pakistani Army.[13] Numerous women were tortured, raped and killed during the war.[122] Bangladeshi sources cite a figure of 200,000 women raped, giving birth to thousands of war-babies. The soldiers of the Pakistan Army and razakars also kept Bengali women as sex-slaves inside the Pakistani Army's camps, and many became pregnant.[8][123] The perpetrators also included Mukti Bahini and the Indian Army, which targeted noncombatants and committed rapes, as well as other crimes.[16]

Among other sources, Susan Brownmiller refers to an estimated number of over 400,000. Pakistani sources claim the number is much lower, though having not completely denied rape incidents.[124][125][126] Brownmiller quotes:[127]

Khadiga, thirteen years old, was interviewed by a photojournalist in Dacca. She was walking to school with four other girls when they were kidnapped by a gang of Pakistani soldiers. All five were put in a military brothel in Mohammadpur and held captive for six months until the end of the war.

In a New York Times report named 'Horrors of East Pakistan Turning Hope into Despair', Malcolm W. Browne[128] wrote:

One tale that is widely believed and seems to come from many different sources is that 563 women picked up by the army in March and April and held in military brothels are not being released because they are pregnant beyond the point at which abortions are possible.

The licentious attitude of the soldiers, although generally supported by their superiors, alarmed the regional high command of the Pakistani Army. On 15 April 1971, in a secret memorandum to the divisional commanders, Niazi complained,

Since my arrival, I have heard numerous reports of troops indulging in looting and arson, killing people at random and without reasons in areas cleared of the anti state elements; of late there have been reports of rape and even the West Pakistanis are not being spared; on 12 April two West Pakistani women were raped, and an attempt was made on two others.[129]

Anthony Mascarenhas published a newspaper article titled 'Genocide in June 1971' in which he also wrote about violence perpetrated by Bengalis against Biharis.[130]

First it was the massacre of the non-Bengalis in a savage outburst of Bengali hatred. Now it was massacre deliberately carried out by the West Pakistan army ... The West Pakistani soldiers are not the only ones who have been killing in East Bengal, of course. On the night of 25 March… the Bengali troops and paramilitary units stationed in East Pakistan mutinied and attacked non-Bengalis with atrocious savagery. Thousands of families of unfortunate Muslims, many of them refugees from Bihar who chose Pakistan at the time of the partition riots in 1947, were mercilessly wiped out. Women were raped, or had their breasts torn out with specially-fashioned knives. Children did not escape the horror; the lucky ones were killed with their parents…

Pakistani Major General Khadim Hussain Raja wrote in his book that Niazi, in presence of Bengali officers would say ‘Main iss haramzadi qom ki nasal badal doonga (I will change the race of the Bengalis)’. A witness statement to the commission read "The troops used to say that when the Commander (Lt Gen Niazi) was himself a raper (sic), how could they be stopped?".[131]

Another work that has included direct experiences from the women raped is Ami Birangona Bolchhi ("I, the heroine, speak") by Nilima Ibrahim. The work includes in its name from the word Birangona (Heroine), given by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman after the war, to the raped and tortured women during the war. This was a conscious effort to alleviate any social stigma the women might face in the society.

There are eyewitness reports of the "rape camps" established by the Pakistani Army.[43] The US based Women Under Siege Project of the Women's Media Center have reported the girls as young as 8 and women as old as 75 were detained in Pakistan military barracks, and where they were victims of mass rape which sometimes culminated in mass murder. The report was based on interview with survivors.[132] Australian Doctor Geoffrey Davis was brought to Bangladesh by the United Nation and International Planned Parenthood Federation to carry out late term abortions on rape victims. He was of the opinion that the 200,000 to 400,000 rape victims were an underestimation. On the actions of Pakistan army he said "They’d keep the infantry back and put artillery ahead and they would shell the hospitals and schools. And that caused absolute chaos in the town. And then the infantry would go in and begin to segregate the women. Apart from little children, all those were sexually matured would be segregated..And then the women would be put in the compound under guard and made available to the troops ... Some of the stories they told were appalling. Being raped again and again and again. A lot of them died in those [rape] camps. There was an air of disbelief about the whole thing. Nobody could credit that it really happened!"[133]

In October 2005, Sarmila Bose published a paper suggesting that the casualties and rape allegations in the war have been greatly exaggerated for political purposes.[52][134] Whilst she received praise from many quarters,[135] a number of researchers have shown inaccuracies in Bose's work, including flawed methodology of statistical analysis, misrepresentation of referenced sources, and disproportionate weight to Pakistani Army testimonies.[136]

A 2014 film titled Children of War focused on the harrowing condition in the 'rape camps' set up by the Anti Separatists.[137]

Historian Christian Gerlach states that "a systematic collection of statistical data was aborted, possibly because the tentative data did not substantiate the claim that three million had died and at least 200,000 women had been raped."[138]

Violence against minorities

US government cables noted that the minorities of Bangladesh, especially the Hindus, were specific targets of the Pakistani Army.[74][105] There was widespread killing of Hindu males, and rapes of women. Documented incidents in which Hindus were massacred in large numbers include the Jathibhanga massacre, the Chuknagar massacre, and the Shankharipara massacre.[139] More than 60% of the Bengali refugees who fled to India were Hindus.[140][141] It has been alleged that this widespread violence against Hindus was motivated by a policy to purge East Pakistan of what was seen as Hindu and Indian influences.[142] Buddhist temples and Buddhist monks were also attacked through the course of the year.[143] Lt. Colonel Aziz Ahmed Khan reported that in May 1971 there was written order to kill Hindus and that General Niazi would ask troops how many Hindus they had killed.[144]

According to R. J. Rummel, professor of political science at the University of Hawaii,

The genocide and gendercidal atrocities were also perpetrated by lower-ranking officers and ordinary soldiers. These "willing executioners" were fueled by an abiding anti-Bengali racism, especially against the Hindu minority. "Bengalis were often compared with monkeys and chickens. Said General Niazi, 'It was a low lying land of low lying people.' The Hindus among the Bengalis were as Jews to the Nazis: scum and vermin that [should] best be exterminated. As to the Moslem Bengalis, they were to live only on the sufferance of the soldiers: any infraction, any suspicion cast on them, any need for reprisal, could mean their death. And the soldiers were free to kill at will. The journalist Dan Coggin quoted one Pakistani captain as telling him, "We can kill anyone for anything. We are accountable to no one." This is the arrogance of Power.[145]

Persecution of Biharis

In 1947, at the time of partition and the establishment of the state of Pakistan, Bihari Muslims, many of whom were fleeing the violence that took place during partition, migrated from India to the newly independent East Pakistan.[146] These Urdu-speaking people were averse to the Bengali language movement and the subsequent nationalist movements because they maintained allegiance toward West Pakistani rulers, causing anti-Bihari sentiments among local nationalist Bengalis. After the convening of the National Assembly was postponed by Yahya Khan on 1 March 1971, the dissidents in East Pakistan began targeting the ethnic Bihari community which had supported West Pakistan.[147]

In early March 1971, 300 Biharis were slaughtered in rioting by Bengali mobs in Chittagong alone.[147] The Government of Pakistan used the 'Bihari massacre' to justify its deployment of the military in East Pakistan on 25 March,[147] when it initiated its infamous Operation Searchlight. When the war broke out in 1971, the Biharis sided with the Pakistani Army. Some of them joined Razakar and Al-Shams militia groups and participated in the persecution and genocide of their Bengali countrymen, in retaliation for atrocities committed against them by Bengalis,[147] including the widespread looting of Bengali properties and abetting other criminal activities.[105] When the war finished Biharis faced severe retaliation, resulting in a counter-genocide and the displacement of over a million non-Bengalis.[75]

According to The Minorities at Risk Project the number of Bihari killed is about 1,000.[18] International estimates vary between 20,000 and 200,000. In June 1971, Bihari representatives stated that 500,000 Biharis were killed by Bengalis.[21] R.J. Rummel gives a prudent estimate of 150,000 killed.[22]

After the war the Government of Bangladesh confiscated the properties of the Bihari Population. There are many reports of massacres of Biharis and alleged collaborators that took place in the period following the surrender of the Pakistani Army on 16 December 1971.[148] In an incident on 18 December 1971, captured on camera and attended by members of the foreign press, Abdul Kader Siddiqui and Kaderia Bahini guerrillas under his command and named after him,[149] bayoneted and shot to death a group of prisoners of war who were accused of belonging to the Razakar paramilitary forces.[150][151]

International reactions

Time reported a high US official as saying "It is the most incredible, calculated thing since the days of the Nazis in Poland."[152] Genocide is the term that is used to describe the event in almost every major publication and newspaper in Bangladesh,[153][154] and is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group"[155]

A 1972 report by the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) noted that both sides in the conflict accused each other of perpetrating genocide. The report observed that it may be difficult to substantiate claims that the "whole of the military action and repressive measures taken by the Pakistani Army and their auxiliary forces constituted genocide' that was intended to destroy the Bengali people in whole or in part, and that 'preventing a nation from attaining political autonomy does not constitute genocide: the intention must be to destroy in whole or in part the people as such." The difficulty of proving intent was considered to be further complicated by the fact that three specific sections of the Bengali people were targeted in killings committed by the Pakistani Army and their collaborators: members of the Awami League, students, and East Pakistani citizens of the Hindu religion. The report observed, however, that there is a strong prima facie case that particular acts of genocide were committed, especially towards the end of the war, when Bengalis were targeted indiscriminately. Similarly, it was felt that there is a strong prima facie case that crimes of genocide were committed against the Hindu population of East Pakistan.[156]

As regards the massacres of non-Bengalis by Bengalis during and after the Liberation War, the ICJ report argued that it is improbable that "spontaneous and frenzied mob violence against a particular section of the community from whom the mob senses danger and hostility is to be regarded as possessing the necessary element of conscious intent to constitute the crime of genocide," but that, if the dolus specialis were to be proved in particular cases, these would have constituted acts of genocide against non-Bengalis.[156]

After the minimum 20 countries became parties to the Genocide Convention, it came into force as international law on 12 January 1951. At that time however, only two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council were parties to the treaty, and it was not until after the last of the five permanent members ratified the treaty in 1988, and the Cold War came to an end, that the international law on the crime of genocide began to be enforced. As such, the allegation that genocide took place during the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 was never investigated by an international tribunal set up under the auspices of the United Nations.

Rudolph Rummel wrote "In 1971, the self-appointed president of Pakistan and commander-in-chief of the army General Agha Mohammed Yahya Khan and his top generals prepared a careful and systematic military, economic, and political operation against East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). They planned to murder that country's Bengali intellectual, cultural, and political elite. They planned to indiscriminately murder hundreds of thousands of its Hindus and drive the rest into India. And they planned to destroy its economic base to insure that it would be subordinate to West Pakistan for at least a generation to come. This despicable and cutthroat plan was outright genocide."[157]

The genocide is also mentioned in some publications outside the subcontinent; for example, The Guinness Book of Records lists the atrocities as one of the largest five genocides in the twentieth century.[158]

U.S. complicity

President Richard Nixon viewed Pakistan as a Cold War ally and, therefore, refused to condemn its actions. From the White House tapes: "The President seems to be making sure that the distrusted State Department would not, on its own, condemn Yahya for killing Bengalis."[79] Nixon and China tried to suppress reports of genocide from East Pakistan.[159] Nixon also relied on American disinterest in what was happening in Pakistan, he said "Biafra stirred up a few Catholics. But you know, I think Biafra stirred people up more than Pakistan, because Pakistan they're just a bunch of brown goddamn Moslems."[160]

The U.S. government secretly encouraged the shipment of weapons from Iran, Turkey, and Jordan to Pakistan, and reimbursed those countries for them[161] despite Congressional objections.[93]

A collection of declassified U.S. government documents, mostly consisting of communications between US officials in Washington, D.C. and in embassies and USIS centers in Dhaka and in India, show that US officials knew about these mass killings at the time and, in fact, used the terms "genocide" and "selective genocide," for example, in the "Blood Telegram."[93] They also show that President Nixon, advised by Henry Kissinger, decided to downplay this secret internal advice, because he wanted to protect the interests of Pakistan as he was apprehensive of India's friendship with the USSR, and he was seeking a closer relationship with China, which supported Pakistan.[162]

In his book The Trial of Henry Kissinger, Christopher Hitchens elaborates on what he saw as the efforts of Kissinger to subvert the aspirations of independence on the part of the Bengalis.[163] Hitchens not only claims that the term genocide is appropriate to describe the results of the struggle, but also points to the efforts of Henry Kissinger in undermining others who condemned the then ongoing atrocities as being a genocide. He also wrote "Kissinger was responsible for the killing of thousands of people, including Sheik Mujibur Rahman".[164]

Some American politicians did speak out. Senator Ted Kennedy charged Pakistan with committing genocide and called for a complete cut-off of American military and economic aid to Pakistan.[165]

War crimes trial attempts

As early as 22 December 1971, the Indian Army was conducting investigations of senior Pakistani Army officers connected to the massacre of intellectuals in Dhaka, with the aim of collecting sufficient evidence to have them tried as war criminals. They produced a list of officers who were in positions of command at the time, or were connected to the Inter-Services Screening Committee.[166]

1972–1975

On 24 December 1971 Home minister of Bangladesh A. H. M. Qamaruzzaman said, "war criminals will not survive from the hands of law. Pakistani military personnel who were involved with killing and raping have to face tribunal." In a joint statement after a meeting between Sheikh Mujib and Indira Gandhi, the Indian government assured that it would give all necessary assistance for bringing war criminals into justice. In February 1972, the government of Bangladesh announced plans to put 100 senior Pakistani officers and officials on trial for crimes of genocide. The list included General A. K. Niazi and four other generals.[167]

After the war, the Indian Army held 92,000 Pakistani prisoners of war,[168] and 195 of those were suspected of committing war crimes. All 195 of them were released in April 1974 following the tripartite Delhi Agreement between Bangladesh, Pakistan and India, and repatriated to Pakistan, in return for Pakistan's recognition of Bangladesh.[169] Pakistan expressed her interest to perform a trial against those 195 officials and furthermore fearing for the fate of 400,000 Bengalis trapped in Pakistan, Bangladesh agreed to handover them to Pakistani authority.[109]

The Bangladeshi Collaborators (Special Tribunals) Order of 1972 was promulgated to bring to trial those Bangladeshis who collaborated with and aided the Pakistani Armed forces during the Liberation War of 1971.[170] There are conflicting accounts of the number of persons brought to trial under the 1972 Collaborators Order, ranging between 10,000 and 40,000.[171] At the time, the trials were considered problematic by local and external observers, because they appear to have been used for carrying out political vendettas. R. MacLennan, a British MP who was an observer at the trials stated that 'In the dock, the defendants are scarcely more pitiable than the succession of confused prosecution witnesses driven (by the 88-year-old defence counsel) to admit that they, too, served the Pakistani government but are now ready to swear blindly that their real loyalty was to the government of Bangladesh in exile.'[172] In May 1973 Pakistan government detained Bengali civil servants stranded in Pakistan and their family members in response to Bangladesh's attempt to try POWs for genocide.[173] Pakistan unsuccessfully pleaded to the International Court of Justice five times to contest Bangladesh's application of the term "genocide".[173]

The government of Bangladesh issued a general amnesty on 30 November 1973, applying it to all persons except those who were punished or accused of rape, murder, attempted murder or arson.[171] The Collaborators Order of 1972 was revoked in 1975.

The International Crimes (Tribunals) Act of 1973 was promulgated to prosecute any persons, irrespective of nationality, who were accused of committing crimes against peace, crimes against humanity, war crimes, "violations of any humanitarian rules applicable in armed conflicts laid out in the Geneva Conventions of 1949" and "any other crimes under international law".[174] Detainees held under the 1972 Collaborators order who were not released by the general amnesty of 1973 were going to be tried under this Act. However, no trials were held, and all activities related to the Act ceased after the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1975.[175]

There are no known instances of criminal investigations or trials outside Bangladesh of alleged perpetrators of war crimes during the 1971 war. Initial steps were taken by the Metropolitan Police to investigate individuals resident in the United Kingdom who were alleged to have committed war crimes according to a Channel 4 documentary film aired in 1995. To date, no charges have been brought against these individuals.[176]

1991–2006

On 29 December 1991 Ghulam Azam, who was accused of being a collaborator with Pakistan in 1971, became the chairman or Ameer of the political party Jamaat-e-Islami of Bangladesh, which caused controversy. This prompted the creation of a 'National Committee for Resisting the Killers and Collaborators of 1971', in the footsteps of a proposal by writer and political activist Jahanara Imam. A mock people's court was formed which on 26 March 1992, found Ghulam Azam guilty in a trial that was criticised widely and sentenced him to death.

A case was filed in the Federal Court of Australia on 20 September 2006 for alleged crimes of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity during 1971 by the Pakistani Armed Forces and its collaborators. Raymond Solaiman & Associates acting for the plaintiff Mr. Solaiman, have released a press statement which among other things says:[177]

We are glad to announce that a case has been filed in the Federal Magistrate's Court of Australia today under the Genocide Conventions Act 1949 and War Crimes Act. This is the first time in history that someone is attending a court proceeding in relation to the [alleged] crimes of Genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity during 1971 by the Pakistani Armed Forces and its collaborators. The Proceeding number is SYG 2672 of 2006. On 25 October 2006, a direction hearing will take place in the Federal Magistrates Court of Australia, Sydney registry before Federal Magistrate His Honor Nicholls.

On 21 May 2007, at the request of the applicant leave was granted to the applicant to discontinue his application filed on 20 September 2006.[178]

2007–present

On 30 July 2009, the Minister of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs of Bangladesh stated that no Pakistanis would be tried under the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act of 1973.[179] This decision has drawn criticism from international jurists, because it effectively gives immunity to the commanders of the Pakistani Army who are generally considered to be ultimately responsible for the majority of the crimes that were committed in 1971.[179]

The International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) is a war crimes tribunal in Bangladesh set up in 2009 to investigate and prosecute suspects for the genocide committed in 1971 by the Pakistan Army and their local collaborators, Razakars, Al-Badr and Al-Shams during the Bangladesh Liberation War.[180] During the 2008 general election, the Awami League (AL) pledged to try war criminals.[181]

The government set up the tribunal after the Awami League won the general election in December 2008 with more than two-thirds majority in parliament. The War Crimes Fact Finding Committee, tasked to investigate and find evidence, completed its report in 2008, identifying 1600 suspects.[182][183] Prior to the formation of the ICT, the United Nations Development Programme offered assistance in 2009 on the tribunal's formation.[184] In 2009 the parliament amended the 1973 act that authorised such a tribunal to update it.[185]

Throughout the years, tens of thousands of mostly young demonstrators, including women, have called for the death penalty for those convicted of war crimes. Non-violent protests supporting this position have occurred in other cities as the country closely follows the trials. The first indictments were issued in 2010.

By 2012, nine leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami, the largest Islamist party in the nation, and two of the Bangladesh National Party, had been indicted as suspects in war crimes.[186] Three leaders of Jamaat were the first tried; each were convicted of several charges of war crimes. The first person convicted was Abul Kalam Azad, tried in absentia as he had left the country; he was sentenced to death in January 2013.[187]

.jpg)

While human rights groups[188] and various political entities[189][190] initially supported the establishment of the tribunal, they have since criticised it on issues of fairness and transparency, as well as reported harassment of lawyers and witnesses representing the accused.[188][191][192][193] Jamaat-e-Islami supporters and their student wing, Islami Chhatra Shibir, called a general strike nationwide on 4 December 2012, in proteat against the tribunal which erupted in nation-wide violence. They demanded that the tribunal be scrapped permanently and their leaders be released immediately.[194][195][196]

One of the most high profile verdict was of Abdul Quader Molla, assistant secretary general of Jamaat, who was convicted in February 2013 and sentenced to life imprisonment culminating in the massive Shahbag protests. The government although initially reluctant, eventually appealed the verdict in the Supreme Court which granted the death sentence. Abdul Quader Molla was subsequently executed on Thursday 12 December 2013 amidst controversies on the legitimacy of the war tribunal hearings drawing wide criticisms from countries such as US, UK and Turkey and also the UN. A period of unrest ensued. The majority of the population were however found to be in favour of the execution.[197]

Salahuddin Quader Chowdhury and Ali Ahsan Mohammad Mujahid, who had both been convicted of genocide and rape, were hanged in Dhaka Central Jail on 22 November 2015 around 12:45 am.[198][199]

Of late, a draft of the Digital Security Act, 2016 has been finalized and has been placed for cabinet approval. The law proposes to declare any propaganda against the War of Liberation as cognizable and non-bailable.[200]

Views in Pakistan

| Part of a series on |

| Denial of mass killings |

|---|

| Instances of denial |

|

| Scholarly controversy over mass killings |

|

| Related topics |

The Hamoodur Rahman Commission set up by the Pakistani government following the war noted various atrocities committed by the Pakistani military, including widespread arson and killings in the countryside, killing of intellectuals and professionals, killing of Bengali military officers and soldiers on the pretence of mutiny, killing Bengali civilian officials, businessmen and industrialists, raping numerous Bengali women as a deliberate act of revenge, retaliation and torture, deliberate killing of members of the Bengali Hindu minority and the creation of mass graves.[201] The Hamoodur Rahman Commission wrote, "indiscriminate killing and looting could only serve the cause of the enemies of Pakistan. In the harshness, we lost the support of the silent majority of the people of East Pakistan.... The Comilla Cantonment massacre (on 27th/28th of March, 1971) under the orders of CO 53 Field Regiment, Lt. Gen. Yakub Malik, in which 17 Bengali Officers and 915 men were just slain by a flick of one Officer's fingers should suffice as an example".[131] The commission's report and findings were suppressed by the Pakistani government for more than 30 years, but were leaked to the Indian and Pakistani media in 2000. However, the commission's lowly death toll of 26,000 was criticised as an attempt to whitewash the war.[80]

Several former West Pakistani Army officers who served in Bangladesh during the 1971 war have admitted to large-scale atrocities by their forces.[131][202][203]

The government of Pakistan continues to deny that the 1971 Bangladesh genocide took place under Pakistan's rule of Bangladesh (East Pakistan) during the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. They typically accuse Pakistani reporters (such as Anthony Mascarenhas) who reported on the genocide of being "enemy agents".[204] According to Donald W. Beachler, professor of political science at Ithaca College:[205]

The government of Pakistan explicitly denied that there was genocide. By their refusal to characterise the mass-killings as genocide or to condemn and restrain the Pakistani government, the US and Chinese governments implied that they did not consider it so.

Similarly, in the wake of the 2013 Shahbag protests against war criminals who were complicit in the genocide, English journalist Philip Hensher wrote[206]

The genocide is still too little known about in the West. It is, moreover, the subject of shocking degrees of denial among partisan polemicists and manipulative historians.

In the 1974 Delhi Agreement, Bangladesh called on Pakistan to prosecute 195 military officers for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide under relevant provisions of international law. Pakistan responded that it "deeply regretted any crimes that may have been committed".[207] It failed to bring the perpetrators to account on its own soil, as requested by Bangladesh. The position taken by Pakistan was reiterated by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1974, when he simply expressed "regret" for 1971, and former Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf in 2002, when he expressed regret for the "excesses" committed in 1971.[208] By 2015, many of those 195 officers were deceased.

The International Crimes Tribunal set up by Bangladesh in 2009 to prosecute surviving collaborators of the pro-Pakistani militias in 1971 has been the subject of strong criticism in Pakistani political and military circles. On 30 November 2015, the government of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif retreated from earlier positions and said that it denies any role by Pakistan in atrocities in Bangladesh.[209] A statement of the Pakistani Foreign Ministry, after summoning the Acting Bangladeshi High Commissioner, said that "Pakistan also rejected insinuation of complicity in committing crimes or war atrocities. Nothing could be further from the truth".[209][210] The statement marked a growing trend of genocide denial in Pakistan, which picked up pace after controversial Indian academic Sarmila Bose accused the Mukti Bahini of war crimes. Bose has claimed that there is greater denial in Bangladesh of war crimes which were committed by Bengalis against Biharis.[80]

Many in Pakistan's civil society have called for an unconditional apology to Bangladesh and an acknowledgement of the genocide, including noted journalist Hamid Mir,[211] human rights activist Asma Jahangir,[212] former Pakistan Air Force chief Asghar Khan,[213] cultural activist Salima Hashmi,[214] and defence analyst Muhammad Ali Ehsan.[215] Asma Jahangir has called for an independent United Nations inquiry to investigate the atrocities. Jahangir also described Pakistan's reluctance to acknowledge the genocide a result of the Pakistani Army's dominant influence on foreign policy.[212] She spoke of the need for closure on the 1971 genocide.[216] Pakistani historian Yaqoob Khan Bangash described the actions of the Pakistani Army during the Bangladesh Liberation war as a "rampage".[62]

Documentaries and films

- Stop Genocide (1971 documentary film)[217][218]

- Major Khaled's war (1971 documentary film)[219][220]

- Nine Months to Freedom: The Story of Bangladesh (1972 documentary film)[221][222]

- Children of War (2014 film) a film portraying the atrocities in the 1971 Bangladesh Genocide.

- Merciless Mayhem:The Bangladesh Genocide Through Pakistani Eyes (2018 TV Movie)[223][224]

See also

- 1971 Dhaka University massacre

- Akhira massacre

- Bakhrabad massacre

- Bengali Genocide Remembrance Day

- Burunga massacre

- Jinjira massacre

- Chuknagar massacre

- The Concert for Bangladesh, the first major benefit concert

- Movement demanding trial of war criminals of Bangladesh : 1972 to present

- Bangladesh Liberation War Library and Research Centre, a Digital Library, working to 'preserve and publicly distribute' the historical documents regarding the Liberation War of Bangladesh and Genocide of Innocent Bengali People in 1971.

References

- Dummett, Mark (16 December 2011). "Bangladesh war: The article that changed history". BBC News. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Samuel Totten; William S. Parsons; Israel W. Charny (2004). Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. Psychology Press. pp. 295–. ISBN 978-0-415-94430-4.

- Sandra I. Cheldelin; Maneshka Eliatamby (18 August 2011). Women Waging War and Peace: International Perspectives of Women's Roles in Conflict and Post-Conflict Reconstruction. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-4411-6021-8.

- "Bangladesh sets up war crimes court – Central & South Asia". Al Jazeera. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- Spencer 2012, p. 63.

- Ganguly 2002, p. 60.

- Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S. (10 September 2012). Centuries of Genocide: Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-24550-4.

- Alston, Margaret (2015). Women and Climate Change in Bangladesh. Routledge. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-317-68486-2.

- "Birth of Bangladesh: When raped women and war babies paid the price of a new nation". 19 December 2016.

- Sisson, Richard; Rose, Leo E. (1991). War and Secession: Pakistan, India, and the Creation of Bangladesh. University of California Press. p. 306. ISBN 9780520076655.

- Sharlach 2000, pp. 92–93.

- Sajjad 2012, p. 225.

- D'Costa 2011, p. 108.

- Tinker, Hugh Russell. "History (from Bangladesh)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "World Population Prostpects 2017". Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. Archived from the original on 6 May 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- Saikia 2011, p. 3.

- Khan, Borhan Uddin; Muhammad Mahbubur Rahman (2010). Rainer Hofmann, Ugo Caruso (ed.). Minority Rights in South Asia. Peter Lang. p. 101. ISBN 978-3631609163.

- "Chronology for Biharis in Bangladesh". The Minorities at Risk (MAR) Project. Archived from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- George Fink (25 November 2010). Stress of War, Conflict and Disaster. Academic Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-12-381382-4.

- Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace and Conflict: Po – Z, index. 3. Academic Press. 1999. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-12-227010-9.

- Gerlach, Christian (2010). Extremely Violent Societies: Mass Violence in the Twentieth-Century World. Cambridge University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-139-49351-2.

- Rummel, R.J. (1997). Death by Government. Transaction Publishers. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-56000-927-6.

- Payaslian.

- Bergman, David (24 April 2014). "Questioning an iconic number". The Hindu. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- Beachler, Donald (1 December 2007). "The politics of genocide scholarship: the case of Bangladesh". Patterns of Prejudice. 41 (5): 467–492. doi:10.1080/00313220701657286.

Some scholars and other writers have denied that what took place in Bangladesh was a genocide.

- Brecher 2008, p. 169.

- Mookherjee 2009, p. 51.

- Jones 2010, p. 340.

- Jones 2010, pp. 227–228.

- Thompson 2007, p. 42.

- Shah 1997, p. 51.

- Hossain & Tollefson 2006, p. 245.

- Enskat, Mitra & Spiess 2004, p. 217.

- Harder 2010, p. 351.

- Haggett 2001, p. 2716.

- Hagerty & Ganguly 2005, p. 31.

- Midlarsky 2011, p. 257.

- Riedel 2011, p. 9.

- Roy 2010, p. 102.

- Filkins, Dexter (27 September 2013). "'The Blood Telegram,' by Gary J. Bass". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Sisson & Rose 1992, p. 141.

- Dasgupta, Abhijit; Togawa, Masahiko; Barkat, Abul (7 June 2011). Minorities and the State: Changing Social and Political Landscape of Bengal. SAGE Publications India. p. 147. ISBN 9788132107668.

- Hensher, Philip (19 February 2013). "The war Bangladesh can never forget". The Independent. London. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Feldstein, Mark (28 September 2010). Poisoning the Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington's Scandal Culture. Macmillan. p. 8. ISBN 9781429978972.

- Hewitt, William L. (2004). Defining the Horrific: Readings on Genocide and Holocaust in the 20th Century. Pearson Education. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-13-110084-8.

- Baxter, Craig (1997). Bangladesh: From A Nation To A State. Westview Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-813-33632-9.

The Pakistanis had armed some groups, Bihari and Bengali, that opposed separation.

- Bose, Sarmila (8 October 2005). "Anatomy of Violence: Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971" (PDF). Economic and Political Weekly. 40 (41): 4463–4471. JSTOR 4417267.

- Bose, Sarmila (November 2011). "The question of genocide and the quest for justice in the 1971 war" (PDF). Journal of Genocide Research. 13 (4): 398. doi:10.1080/14623528.2011.625750.

- "The Demolition of Ramna Kali Temple in March 1971". Asian Tribune. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- "Last Word: Gary J. Bass". Newsweek Pakistan. 17 December 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Gill, John H (1994). An Atlas of 1971 Indian-Pakistan war-the Creation of Bangladesh. NESA. p. 66.

- Bose, Sarmila (8 October 2005). "Anatomy of Violence: Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971". Economic and Political Weekly. Archived from the original on 1 March 2007.

- D' Costa, Bina (2011). Nationbuilding, Gender and War Crimes in South Asia. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 9780415565660.

- Cowasjee, Ardeshir (17 September 2000). "Gen Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan – 4". Dawn. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- "Ahsan, Vice Admiral Syed Muhammad – Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Roberts, Sam (28 January 2016). "Sahabzada Yaqub Khan, Pakistani Diplomat, Dies at 95". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Editorial (27 January 2016). "Sahibzada Yaqub Khan". Dawn. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- "Bio – Sarmila Bose". Sarmila Bose. 8 February 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- Mookherjee, Nayanika (8 June 2011). "This account of the Bangladesh war should not be seen as unbiased". The Guardian.

- Bose, Sarmila (8 October 2005). "Anatomy of Violence: Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971" (PDF). Economic and Political Weekly: 4464–4465.

- Bose, Sarmila. "'Smriti Irani misrepresented my work in her speech': Oxford researcher Sarmila Bose". Scroll.in. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- "No lessons learnt in forty years". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- "The Black Night that still haunts the nation". The Daily Star. 25 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- Chandan, Md Shahnawaz Khan (8 March 2015). "The Heroes of a Forgetful Nation". The Daily Star. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- Russell, Malcolm (2015). The Middle East and South Asia 2015–2016. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-4758-1879-6.

- Abhijit Dasgupta; Masahiko Togawa; Abul Barkat (7 June 2011). Minorities and the State: Changing Social and Political Landscape of Bengal. SAGE Publications. p. 147. ISBN 978-81-321-0766-8.

- Sālik, Ṣiddīq (1997). Witness To Surrender. Dhaka: University Press. pp. 63, 228–229. ISBN 978-984-05-1373-4.

- Pakistan Defence Journal, 1977, Vol 2, p2-3

- Jones, Owen Bennett (2003). Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-300-10147-8.

- Anam, Tahmima (26 December 2013). "Pakistan's State of Denial". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Tharoor, Ishaan. "Forty Years After Its Bloody Independence, Bangladesh Looks to Its Past to Redeem Its Future". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- "World: Pakistan: The Ravaging of Golden Bengal". Time. 2 August 1971. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Mahtab, Moyukh (23 December 2015). "The burden of remembrance". The Daily Star. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- U.S. Consulate (Dacca) Cable, Sitrep: Army Terror Campaign Continues in Dacca; Evidence Military Faces Some Difficulties Elsewhere, 31 March 1971, Confidential, 3 pp

- Willem van Schendel (2009). A History of Bangladesh. Cambridge University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-316-26497-3.

- "Alleged atrocities by the Pakistan Army (paragraph 33)". Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report. 23 October 1974. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Totten, Samuel (2012). Plight and Fate of Women During and Following Genocide. Transaction Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4128-4759-9.

- Myers (2004). Exploring Social Psychology 4E. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-07-070062-8.

- Bass, Gary (19 November 2013). "Looking Away from Genocide". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- "Controversial book accuses Bengalis of 1971 war crimes". BBC News. 16 June 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- Jack, Ian (20 May 2011). "It's not the arithmetic of genocide that's important. It's that we pay attention". The Guardian.

- "Bose is more Pakistani than Jinnah the Quaid". The Sunday Guardian. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- Mohaiemen, Naeem (3 October 2011). "Flying Blind: Waiting for a Real Reckoning on 1971". The Daily Star. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- "This account of the Bangladesh war should not be seen as unbiased". The Guardian. 8 June 2011. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Obermeyer, Ziad; et al. (June 2008). "Fifty years of violent war deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia: analysis of data from the world health survey programme". British Medical Journal. 336 (7659): 1482–1486. doi:10.1136/bmj.a137. PMC 2440905. PMID 18566045.

- Mukhopadhay, Keshab (13 May 2005). "An interview with prof. Ahmed sharif". News from Bangladesh. Daily News Monitoring Service. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Beachler, Donald W. (2011). The genocide debate : politicians, academics, and victims (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-230-11414-2.

- Many of the eyewitness accounts of relations that were picked up by "Al Badr" forces describe them as Bengali men. The only survivor of the Rayerbazar killings describes the captors and killers of Bengali professionals as fellow Bengalis. See 37 Dilawar Hossain, account reproduced in 'Ekattorer Ghatok-dalalera ke Kothay' (Muktijuddha Chetona Bikash Kendro, Dhaka, 1989)

- Khan, Asadullah (14 December 2005). "The loss continues to haunt us". The Daily Star (Point-Counterpoint).

- Tahmima Anam (13 February 2013). "Shahbag protesters versus the Butcher of Mirpur". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- "Crimes of War – Bangladesh: A Free and Fair War Crimes Tribunal?". crimesofwar.org. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- DPA report (8 August 1999). "Mass grave found in Bangladesh". The Chandigarh Tribune.

- Gandhi, Sajit, ed. (16 December 2002). "The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971". National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 79. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- "Cable from U.S. Consulate in Dacca: Selective Genocide" (PDF). National Security Archive. 27 March 1971. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- Telegram 959 From the US Consulate General in Dacca to the Department of State, 28 March 1971, 0540Z ("Selective Genocide")

- "Office of the Historian". Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- Baxter, Craig (1997). Bangladesh: From A Nation To A State. Westview Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-813-33632-9.

- LINTNER, BERTIL (2004). "Religious Extremism and Nationalism in Bangladesh" (PDF). p. 418.

- Kalia, Ravi (2012). Pakistan: From the Rhetoric of Democracy to the Rise of Militancy. Routledge. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-136-51641-2.

- Schmid 2011, p. 600.

- Tomsen 2011, p. 240.

- Mookherjee 2009, p. 49.

- Ḥaqqānī 2005, p. 77.

- Shehabuddin 2010, p. 93.

- "Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–7, Documents on South Asia, 1969–1972 – Office of the Historian". history.state.gov.

- Ajoy Roy, "Homage to my martyr colleagues", 2002

- "125 Slain in Dacca Area, Believed Elite of Bengal". The New York Times. New York, NY, USA. 19 December 1971. p. 1. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

At least 125 persons, believed to be physicians, professors, writers and teachers were found murdered today in a field outside Dacca. All the victims' hands were tied behind their backs and they had been bayoneted, garroted or shot. They were among an estimated 300 Bengali intellectuals who had been seized by West Pakistani soldiers and locally recruited

- Murshid, Tazeen M. (1997). "State, nation, identity: The quest for legitimacy in Bangladesh". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 20 (2): 1–34. doi:10.1080/00856409708723294. ISSN 1479-0270.

- Khan, Muazzam Hussain (2012). "Killing of Intellectuals". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Shaiduzzaman (14 December 2005), "Martyred intellectuals: martyred history" Archived 1 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily New Age, Bangladesh

- Askari, Rashid (14 December 2005). "Our martyerd intellectuals". The Daily Star (Editorial).

- Dr. M.A. Hasan, Juddhaporadh, Gonohatya o bicharer anneshan, War Crimes Fact Finding Committee and Genocide archive & Human Studies Centre, Dhaka, 2001

- Shahiduzzaman No count of the nation's intellectual loss Archived 1 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine The New Age, 15 December 2005

- "Gallows for Mueen, Ashraf". The Daily Star. 3 November 2013.

- "Story of a Martyred Intellectual of 71's war". Adnan's Den. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- "ICT issues arrest order against Mueen, Ashrafuzzaman". Daily Sun. 3 May 2013. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- Khan, Tamanna (4 November 2013). "It was matricide". The Daily Star. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- D'Costa 2011, pp. 120–121.

- Islam, Kajalie Shehreen (2012). "Breaking Down the Birangona: Examining the (Divided) Media Discourse on the War Heroines of Bangladesh's Independence Movement". International Journal of Communication. 6: 2131. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Martin, Susan Forbes; Tirman, John (2009). Women, Migration, and Conflict: Breaking a Deadly Cycle. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 173. ISBN 978-90-481-2825-9.

- Bodman & Tohidi 1998, p. 208.

- "BANGLADESH GENOCIDE 1971 – RAPE VICTIMS Interview". 15 December 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2013 – via YouTube.

- "East Pakistan: Even the Skies Weep". Time. 25 October 1971.

- Debasish Roy Chowdhury 'Indians are bastards anyway' in Asia Times 23 June 2005 "In Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape, Susan Brownmiller likens it to the Japanese rapes in Nanjing and German rapes in Russia during World War II. "... 200,000, 300,000 or possibly 400,000 women (three sets of statistics have been variously quoted) were raped.""

- Brownmiller, Susan, "Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape" ISBN 0-449-90820-8, page 81

- Hamoodur Rahman Commission Archived 16 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Chapter 2 Archived 12 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Paragraphs 32,34

- "[Genocide/1971] Susan Brownmiller: Against Our Will – Men, Women and Rape". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- Browne, Malcolm W. (14 October 1971). "Horrors of East Pakistan Turning Hope into Despair" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Mamoon, Muntassir; (translation by Kushal Ibrahim) (June 2000). The Vanquished Generals and the Liberation War of Bangladesh (First ed.). Somoy Prokashon. p. 30. ISBN 978-984-458-210-1.

- Anthony Mascarenhas, Sunday Times, 13 June 1971

- "Genocide they wrote". The Daily Star. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- "Why is the mass sexualized violence of Bangladesh's Liberation War being ignored?". Women in the World in Association with The New York Times – WITW. 25 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- "1971 Rapes: Bangladesh Cannot Hide History". Forbes. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- "New impartial evidence debunks 1971 rape allegations against groups working for Pakistan and also some members of the Pakistani Army". Daily Times. 2 July 2005.

- Woollacott, Martin (1 July 2011). "Dead Reckoning by Sarmila Bose – review". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Khatun, Salma. "Sarmila Bose rewrites history". Drishtipat. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007.

- Joshi, Namrata (2 June 2014). "Children of War". Outlook. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Gerlach, Christian (2010). Extremely Violent Societies: Mass Violence in the Twentieth-Century World. Cambridge University Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-521-70681-0.

- Bose, Sarmila (2011). Dead Reckoning: Memories of the 1971 Bangladesh War. London: Hurst and Co. pp. 73, 122.

- U.S. State Department, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XI, "South Asia Crisis, 1971", page 165

- Kennedy, Senator Edward, "Crisis in South Asia – A report to the Subcommittee investigating the Problem of Refugees and Their Settlement, Submitted to U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee", 1 November 1971, U.S. Govt. Press, page 66. Sen. Kennedy wrote, "Field reports to the U.S. Government, countless eye-witness journalistic accounts, reports of International agencies such as World Bank and additional information available to the subcommittee document the reign of terror which grips East Bengal (East Pakistan). Hardest hit have been members of the Hindu community who have been robbed of their lands and shops, systematically slaughtered, and in some places, painted with yellow patches marked 'H'. All of this has been officially sanctioned, ordered and implemented under martial law from Islamabad."

- Mascarenhas, Anthony (13 June 1971). "Genocide". The Times. London.

The Government's policy for East Bengal was spelled out to me in the Eastern Command headquarters at Dacca. It has three elements: 1. The Bengalis have proved themselves unreliable and must be ruled by West Pakistanis; 2. The Bengalis will have to be re-educated along proper Islamic lines. The – Islamization of the masses – this is the official jargon – is intended to eliminate secessionist tendencies and provide a strong religious bond with West Pakistan; 3. When the Hindus have been eliminated by death and flight, their property will be used as a golden carrot to win over the under privileged Muslim middle-class. This will provide the base for erecting administrative and political structures in the future.

- "Bangladesh: A Bengali Abbasi Lurking Somewhere?". South Asia Analysis Group. 23 April 2001. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010.

- Jones, Owen Bennett (2003). Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-300-10147-8.

- DEATH BY GOVERNMENT, by R.J. Rummel New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1994

- Hasan, Bijoyeta Das, Khaled. "In Pictures: Plight of Biharis in Bangladesh". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- D'Costa 2011, p. 103.

- ICJ EAST PAKISTAN 1971 REPORT, supra note 5, at 44–45, quoted in S. Linton, Criminal Law Forum (2010), p. 205.

- Ahsan, Syed Badrul (28 March 2012). "Old images from a long-ago war". The Daily Star. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Stanhope, Henry (20 December 1971). "Mukti Bahini Bayonet Prisoners After Prayers". The Times. London. p. 4.

[Dateline: Dec 19] Four Razakar prisoners, who were bayoneted publicly after a rally yesterday ... The leader of the Mukti Bahini ... took part, casually beating the prisoners with has swagger stick before borrowing a bayonet to lunge at one of the trussed-up men. The leader, Mr Abdul Qader Siddiqui, the Mukti commander-in-chief for Dacca, Tangail, Mymensingh and Pusur, whose 'troops' are known as the Qaderi ... Mr Saddiqui's Mukti guards ... fixed bayonets and charged at the prisoners ... They stabed [sic] them through the neck, the chest, the stomach. One of the guards, dismayed at having no bayonet, shot one of the prisoners in the stomach with his sten gun. The crowd watched with interest and the photographers snapped away.

- International Commission of Jurists, the Events in Pakistan: A Legal Study by the Secretariat of the International Commission of Jurists 9 (1972)

- "Pakistan: The Ravaging of Golden Bengal". Time. 2 August 1971.

- Rabbee, N. (16 December 2005). "Remembering a Martyr". Star Weekend Magazine. The Daily Star. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- "The Jamaat Talks Back". The Bangladesh Observer (Editorial). 30 December 2005. Archived from the original on 23 January 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- Funk, T. Marcus (2010). Victims' Rights and Advocacy at the International Criminal Court. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973747-5.

- International Commission of Jurists, "The Events in Pakistan: A Legal Study By The Secretariat Of The International Commission Of Jurists" 9 (1972), p. 56–57., cited in S. Linton, "Completing the Circle: Accountability for the Crimes of the 1971 Bangladesh War of Liberation," Criminal Law Forum (2010) 21:191–311, p. 243.

- Rummel, R. J. (1994). Death by Government: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900. Transaction Publishers. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-56000-145-4.

- Guinness World Records (2006). Guinness World Records 2007. London: Guinness World Records Ltd. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-1-904994-12-1.

- "US, China suppressed genocide reports during Bangladesh liberation war". Zee News. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Mishra, Pankaj (23 September 2013). "Unholy Alliances". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Black, Conrad, "Richard Nixon: A Life in Full" (New York: PublicAffairs, 2007), p. 756.

- "Memorandam for the Record" (PDF). 11 August 1971. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- "The toxic cult of America's national interest". theweek.com. 23 January 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Nabi, Waheed (21 October 2013). "America's role in Mujib murder". The Daily Star. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- "Kennedy Charges Genocide in Pakistan, Urges Aid Cutoff" (PDF). The Washington Post. 17 August 1971. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2013. Alt URL

- Dring, S. (23 December 1971). "Pakistani officers on list for war crimes trials". The Times. London. p. 5.

- "100 face genocide charges". The Times. London. 23 February 1972. p. 7.

- Kharas, J. G. (11 May 1973). "Case Concerning Trial of Pakistani Prisoners of War (Pakistan v. India): Request for the Indication of Interim Measures of Protection" (PDF). International Court of Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Linton, Suzannah (2010). "Completing the circle: accountability for the crimes of the 1971 Bangladesh war of liberation". Criminal Law Forum. 21 (2): 203. doi:10.1007/s10609-010-9119-8. hdl:10722/124770. SSRN 2036374.

- President's Order No. 8 of 1972 (1972) (Bangl.); Collaborators (Special Tribunals) Order (1972) (Bangl.).

- S. Linton, Criminal Law Forum (2010), p. 205.

- A. Mascarenhas, 'Bangladesh: A Legacy of Blood', Hodder and Stoughton, 1986, p. 25.

- "How We Shortchanged Bangladesh". Newsweek Pakistan. 4 August 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- S. Linton, Criminal Law Forum (2010), p. 206.

- "Gwynne Dyer: Genocide trials in Bangladesh". Georgia Straight Vancouver's News & Entertainment Weekly. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- "Torture in Bangladesh 1971–2004: Making International Commitments a Reality and Providing Justice and Reparations to Victims". REDRESS. August 2004. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- Raymond Faisal Solaiman v People's Republic of Bangladesh & Ors Archived 14 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine In The Federal Magistrates Court of Australia at Sydney.

- This judgement can be found via the Federal Court of Australia home page Archived 3 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine by following the links and using SYG/2672/2006 as the key for the database

- S. Linton, Criminal Law Forum (2010), p. 228.

- Wierda, Marieke; Anthony Triolo (31 May 2012). Luc Reydams; Jan Wouters; Cedric Ryngaert (eds.). International Prosecutors. Oxford University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0199554294.

- Kibria, Nazli (2011). Muslims in Motion: Islam and National Identity in the Bangladeshi Diaspora. Rutgers University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0813550565.

The landslide victory of the Awami League in the 2008 election included a manifesto pledge to prosecute the war criminals of 1971.

- Rahman, Syedur; Craig Baxter (2010). Historical dictionary of Bangladesh (4th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-8108-6766-6.

- Montero, David (14 July 2010). "Bangladesh arrests are opening act of war crimes tribunal". The Christian Science Monitor.

- D'Costa 2011, p. 76.

- "Will ban on Islamic party heal wounds?". Deutsche Welle. 18 February 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- "Bangladesh Islamic party leaders indicted on war crimes charges". CBC. The Associated Press. 28 May 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Mustafa, Sabir (2013). "Bangladesh cleric Abul Kalam Azad sentenced to die for war crimes". BBC News. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Adams, Brad (18 May 2011). "Letter to the Bangladesh Prime Minister regarding the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act". Human Rights Watch.

- Haq, M. Zahurul (5 August 2011). M.N. Schmitt; Louise Arimatsu; T. McCormack (eds.). Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law – 2010 (1st ed.). Springer. p. 463. ISBN 978-9067048101.

- Ullah, Ansar Ahmed (3 February 2012). "Vote of trust for war trial". The Daily Star.

- Adams, Brad (2 November 2011). "Bangladesh: Stop Harassment of Defense at War Tribunal". Thomson Reuters Foundation. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013.

- Karim, Bianca; Tirza Theunissen (29 September 2011). Dinah Shelton (ed.). International Law and Domestic Legal Systems: Incorporation, Transformation, and Persuasion. Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0199694907.

- Ghafour, Abdul (31 October 2012). "International community urged to stop 'summary executions' in Bangladesh". Arab News.

- "Jamaat, Shibir go berserk". The Daily Star. 13 November 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Jamaat-Shibir men run amok". New Age. 14 November 2012. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Jamaat desperately on the offensive". The Daily Sun. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2013.