Armenian Oblast

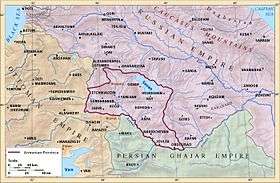

The Armenian Oblast or Armenian Province (Armenian: Հայկական մարզ, Russian: Армянская область) was an oblast (province) of the Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire that existed from 1828 to 1840.[1][2][3] It corresponded to most of present-day central Armenia, the Iğdır Province of Turkey, and the Nakhichevan exclave of Azerbaijan. Its administrative center was Erivan (Yerevan).[4]

Armenian Oblast Армянская область

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Russia |

| Political status | Oblast |

| Region | Caucasus |

| Established | 1828 |

| Abolished | 1840 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 31,672 km2 (12,229 sq mi) |

| Population (1832) | |

| • Total | 164,500 |

| • Density | 5.2/km2 (13/sq mi) |

History

The Armenian Oblast was created out of the territories of the former Erivan and Nakhichevan khanates, which were ceded to Russia by Persia under the Treaty of Turkmenchay after the Russo-Persian War of 1826-1828.[5][6] Ivan Paskevich, the Ukrainian-born military leader and hero of the war, was made "Count of Erivan" in the year of the oblast's creation.[3][5]

In 1829, Baltic German explorer Friedrich Parrot of the University of Dorpat (Tartu) traveled to the oblast as part of his expedition to climb Mount Ararat. Accompanied by Armenian writer Khachatur Abovian and four others, Parrot made the first ascent of Ararat in recorded history from the Armenian monastery of St. Hakob in Akhuri (modern Yenidoğan).[7]

The oblast was dissolved in 1840 and its territory incorporated into a larger new province, the Georgia-Imeretia Governorate.[3] This new division did not last long. In 1844, the Caucasus Viceroyalty was re-established, in which the former Armenian Oblast formed a subdivision of the Tiflis Governorate. In 1849, the Erivan Governorate was established, separate from the Tiflis Governorate.[8] It included the territory of the former Erivan and Nakhichievan khanates.[9]

Demographics

In order to gain demographic information on the newly-acquired Armenian territory, the Tsarist authorities dispatched Ivan Chopin to the oblast in 1829 to conduct a census of the population.[10] Muslims, including Tatars (today Azerbaijanis), Kurds, and Persians, formed the majority of the population, while Christian Armenians formed a very significant minority. [2] The number of Armenians increased significantly after the Russian government allowed and encouraged Armenians living in Persian and Turkish territory to migrate into Russian Transcaucasia. Armenian captives who had lived in Persia since 1804 or even as far back as 1795 were permitted to return.[11] By 1832, about 45,000 Armenians had resettled in the oblast.[12]

Literature

- A Journey to Arzrum, Alexander Pushkin, 1835–36

- Wounds of Armenia, Khachatur Abovian, 1841

References

- Tsutsiev, Arthur (2014). Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus. Translated by Nora Seligman Favorov. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780300153088.

- Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 122. ISBN 9780231139267.

- Bournoutian, George A. (1992). The Khanate of Erevan Under Qajar Rule, 1795-1828. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers. p. 26. ISBN 9780939214181.

- Tsutsiev, p. 16.

- King, Charles (2008). The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0195177756.

- Atkin, Muriel (1980). Russia and Iran, 1780–1828. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 158–159. ISBN 9780816609246.

- Parrot, Friedrich (2016) [1846]. Journey to Ararat. Translated by William Desborough Cooley. Introduction by Pietro A. Shakarian. London: Gomidas Institute. p. 139. ISBN 9781909382244.

- Tsutsiev, p. 20.

- Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780226332284.

- Bournoutian, p. 48.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1991). "Iranian Relations with Russia and the Soviet Union, to 1921". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 7: From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 339. ISBN 9780521200950.

- Bournoutian, p. 60.