Talaat Pasha

Mehmed Talaat (Ottoman Turkish: محمد طلعت, romanized: Mehmed Talât; 1 September 1874 – 15 March 1921), commonly known as Talaat Pasha (Ottoman Turkish: طلعت پاشا; Turkish: Talât Paşa), was one of the triumvirate known as the Three Pashas that de facto ruled the Ottoman Empire during the First World War.[1] He was one of the leaders of the Young Turks and ruled the empire during the Armenian Genocide, which he initiated as Minister of Interior Affairs in 1915.

Mehmed Talaat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire | |

| In office 4 February 1917 – 8 October 1918 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed V Mehmed VI |

| Preceded by | Said Halim Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ahmed Izzet Pasha |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office November 1914 – 4 February 1917 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed V |

| Preceded by | Mehmet Cavit Bey |

| Succeeded by | Abdurrahman Vefik Sayın |

| Minister of Interior | |

| In office 23 January 1913 – 4 February 1917 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed V |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 September 1874 Kırcaali, Adrianople Vilayet, Ottoman Empire (modern Kardzhali, Kardzhali Province, Bulgaria) |

| Died | 15 March 1921 (aged 46) Berlin, Germany |

| Nationality | Ottoman |

| Political party | Committee of Union and Progress |

| Spouse(s) | Hayriye Talat Bafralı |

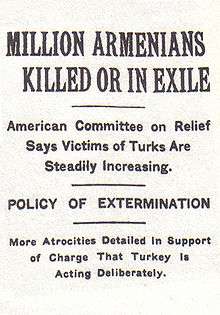

His career in Ottoman politics began by becoming deputy for Adrianople (Edirne) in 1908, then minister of the interior and minister of finance, and finally grand vizier (equivalent to prime minister) in 1917.[1] Acting as the minister of interior, Talaat Pasha ordered on 24 April 1915 the arrest and deportation of Armenian intellectuals in Constantinople (now Istanbul), most of them being ultimately murdered, and on 30 May 1915 requested the Tehcir Law (Temporary Deportation Law); these events initiated the Armenian Genocide. He is widely considered the main perpetrator of the genocide,[2][3][4][5][6] and thus is held responsible for the death of between 800,000 and 1,800,000[7][8][9][10] Armenians.

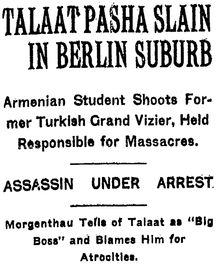

On the night of 2–3 November 1918 and with the aid of Ahmed Izzet Pasha, Talaat Pasha and Enver Pasha (the two main perpetrators of the genocide) fled the Ottoman Empire. Talaat was assassinated in Berlin in 1921 by Soghomon Tehlirian, a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, as part of Operation Nemesis.[1]

Early life

Mehmed Talaat was born in 1874 in Kırcaali town of Adrianople (Edirne) Vilayet into a family of Pomak and Gypsy descent.[11][12] His father was a junior civil servant working for the government of the Ottoman Empire and was from a village in the mountainous southeastern corner of present-day Bulgaria. Mehmed Talaat had a powerful build and a dark complexion.[13] His manners were gruff, which caused him to leave the civil preparatory school without a certificate after a conflict with his teacher. Without earning a degree, he joined the staff of the telegraph company as a postal clerk in Adrianople. His salary was not high, so he worked after hours as a Turkish language teacher in the Alliance Israelite School which served the Jewish community of Adrianople.[13]

At the age of 21 he had a love affair with the daughter of the Jewish headmaster for whom he worked. He was caught sending a telegram saying "Things are going well. I'll soon reach my goal." With two of his friends from the post office, he was charged with tampering with the official telegraph and arrested in 1893. He claimed that the message in question was to his girlfriend. The Jewish girl came forward to defend him. Sentenced to two years in jail, he was pardoned but exiled to Salonica (Thessaloniki) as a postal clerk.[13]

He married Hayriye Hanım (later known as Hayriye Talaat Bafralı), a young girl from Ioannina on 19 March 1910.[14]

Between 1898 and 1908 he served as a postman on the staff of the Salonica Post Office. Eventually, having served 10 years at this postal unit, he became head of the Salonica Post Office.[15]

Young Turk Revolution

In 1908, he was dismissed from membership in the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the nucleus of the Young Turks movement. However, after the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, he became deputy for Adrianople in the Ottoman Parliament, and in July 1909, he was appointed minister of interior affairs. He became minister of posts, and then secretary-general of the CUP in 1912.

After the assassination of the prime minister (grand vizier), Mahmud Şevket Pasha, in July 1913, Talaat Pasha again became minister of interior affairs. Talaat, with Enver Pasha and Djemal Pasha, formed a group later known as the Three Pashas. These men formed the triumvirate that ran the Ottoman government until the end of World War I in October 1918.

Armenian Genocide

According to various sources, Talaat Pasha had developed plans to eliminate the Armenians as early as 1910. Danish philologist Johannes Østrup wrote in his memoirs that in the autumn of 1910, Talaat talked openly about his plans to "exterminate" the Armenians with him.[16][17] According to Østrup, Talaat stated: "If I ever come to power in this country, I will use all my might to exterminate the Armenians."[16][17] In November of that year, a decision to carry out such a plan was made in Salonica (Thessaloniki) where a secret conference was held by prominent members of the CUP. The conference concluded that the Ottoman Empire, which promoted equality among Muslims and non-Muslims alike, was not ideologically compatible anymore, and that the Ottoman Empire should adopt a policy of Turkification.[18] Talaat, who attended the conference, was a leading advocate of this policy shift and stated in a speech that "there can be no question of equality, until we have succeeded in our task of ottomanizing the Empire."[19] Such a decision ultimately required the assimilation of non-Turkish elements within the empire and if necessary, it could be done through force.[18] British ambassador Gerard Lowther concluded after the conference, "[that the] committee have given up any idea of Ottomanizing all the non-Turkish elements by sympathetic and Constitutional ways has long been manifest. To them 'Ottoman' evidently means 'Turk' and their present policy of 'Ottomanization' is one of pounding the non-Turkish elements in a Turkish mortar."[19][20]

Talaat, along with Enver and Cemal, eventually represented the radical faction of the committee. In 1913, the faction ultimately seized power through a violent coup establishing the rule of the Three Pashas, which was also known as the "dictatorial triumvirate".[21] The Three Pashas then became largely responsible for the Ottoman Empire's entry into World War I. With the start of World War I, the Three Pashas found a suitable opportunity to begin their campaign of exterminating the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire.[21][22][23][24]

On 24 April 1915, Talaat issued an order to close all Armenian political organizations operating within the Ottoman Empire and arrest Armenians connected to them, justifying the action by stating that the organizations were controlled from outside the empire, were inciting upheavals behind the Ottoman lines, and were cooperating with Russian forces. This order resulted in the arrest on the night of 24–25 April 1915 of 235 to 270 Armenian community leaders in Constantinople (Istanbul), including politicians, clergymen, physicians, authors, journalists, lawyers, and teachers, the majority of whom were eventually murdered.[25] Although the mass killings of Armenian civilians had begun in the vilayet of Van several weeks earlier, these mass arrests in Constantinople are considered by many commentators to be the start of the Armenian Genocide.[25][26][27]

Talaat then issued the order for the Tehcir Law of 1 June 1915 to 8 February 1916 that allowed for the mass deportation of Armenians, a principal means of carrying out the Armenian Genocide.[28] The deportees did not receive any humanitarian assistance and there is no evidence that the Ottoman government provided the extensive facilities and supplies that would have been necessary to sustain the life of hundreds of thousands of Armenian deportees during their forced march to the Syrian desert or after.[27][29] Meanwhile, the deportees were subject to periodic rape and massacre, often the result of direct orders by the CUP. Talaat, who was a telegraph operator from a young age, had installed a telegraph machine in his own home and sent "sensitive" telegrams during the course of the deportations.[22][30] This was confirmed by Talaat's wife Hayriye, who stated that she often saw him using it to give direct orders to what she believed were provincial governors.[31] In a session of the Ottoman parliament, Ottoman statesman Reshid Akif Pasha testified that he had uncovered documents which demonstrated the process by which official statements made use of vague terminology when ordering deportation only to be clarified by special orders of "massacres" sent directly from CUP headquarters or often from the residence of Talaat himself.[32] He testified:

While humbly occupying my last post in the Cabinet, which barely lasted 25 to 30 days, I became cognizant of some secrets. I came across something strange in this respect. It was this official order for deportation, issued by the notorious Interior Ministry and relayed to the provinces. However, following [the issuance of] this official order, the Central Committee [of Union and Progress] undertook to send an ominous circular order to all points [in the provinces], urging the expediting of the execution of the accursed mission of the brigands. Thereupon, the brigands proceeded to act and the atrocious massacres were the result.[33][n 1]

Hasan Tahsin Uzer, Governor of Erzurum, similarly testified during the Mamuretulaziz (now Elazig) trial that the special forces unit Special Organization (Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa), under the command of Behaeddin Shakir, was mobilized to kill Armenians and that this organization was in constant contact with the Ministry of Interior. He explained:

Then there was another Teskilat-ı Mahsusa, and that one had Bahaeddin Sakir's signature on it. In other words, he was sending telegrams around as the head of the Teskilat-ı Mahsusa...Bahaeddin Sakir had a code. He'd communicate with the Sublime Porte and with the Ministry of the Interior with it.[34]

Other sources also point to such telegrams directing massacre being sent from Talaat Pasha. Rafael de Nogales Méndez, a Venuzelan officer who served the Ottoman Army, visited Diyarbakır on 26 June 1915 and spoke with the governor Mehmet Reşid, who was later known as the "butcher of Diyarbakir".[35][36] Nogales Méndez recounts in his memoirs that Reşid mentioned to him that he received a telegram directly from Talaat ordering him to "burn-destroy-kill".[20][37] Abdulahad Nuri, an official in charge of the deportations, testified during the Turkish courts-martial of 1919–20 that he had been told by Talaat that the goal of the deportations was "extermination" and that he "personally received the orders of extermination" from Talaat himself.[38][n 2] In many instances, there had been additional instructions to "destroy" the telegrams after they had been read.[32]

Numerous diplomats and notable figures confronted Talaat Pasha over the deportations and news of massacres. In one such conversation with German Embassy representative Mordtmann, Talaat stated his aims of annihilating the Christians of Turkey under the cover of World War I:

"Turkey is taking advantage of the war in order to thoroughly liquidate its internal foes, i.e., the indigenous Christians, without being thereby disturbed by foreign intervention."[39][40]

In a memorandum sent to Berlin demanding the removal of German ambassador Paul Wolff Metternich because he interceded on behalf of the Armenians, Talaat reaffirmed such a commitment: "the work must be done now, after the war it will be too late."[41] By the end of the war, the subsequent German ambassador Johann von Bernstorff described his discussion with Talaat: "When I kept on pestering him about the Armenian question, he once said with a smile: 'What on earth do you want? The question is settled, there are no more Armenians'".[42] A similar statement by Talaat was made to Swedish military attaché Einar af Wirsén: "The way the Armenian problem was solved was hair-raising. I can still see in front of me Talaat's cynical expression, when he emphasized that the Armenian question was solved."[43][44] Talaat is reported to have said the following to American ambassador Henry Morgenthau, Sr. (as recorded in Ambassador Morgenthau's Story), who confronted Talaat on several occasions: "I have accomplished more toward solving the Armenian problem in three months than Abdulhamid II accomplished in thirty years!"[45] Morgenthau then relates an exchange he had with Talaat:

"Suppose a few Armenians did betray you," I said. "Is that a reason for destroying a whole race? Is that an excuse for making innocent women and children suffer?" "Those things are inevitable," he replied.[46]

In another exchange, Talaat demanded from Morgenthau the list of the holders of American insurance policies belonging to dead Armenians in an effort to appropriate the funds to the state. Morgenthau categorically refused his request describing it as "one of the most astonishing requests I have ever heard."[47]

Notable Turkish politicians and figures also condemned the policy. Turkish feminist Halide Edip, writing in her memoirs, captured a defiant reaction from Talaat Pasha when she probed him on the deportations and extermination. He allegedly told her that he was of the conviction that as long as a nation does what is best for its own interests and succeeds, the world admires it.[48] Abdülmecid II, the last Caliph of Islam of the Ottoman Dynasty, said: "I refer to those awful massacres. They are the greatest stain that has ever disgraced our nation and race. They were entirely the work of Talat and Enver."[49]

Turkification

Talaat Pasha was also a leading force in the Turkification and deportation of Kurds. In 1916 he was a major force behind the policies regarding the resettlements of Kurds and wanted to be informed whether the Kurds would really be turkifyed or not and how they get along with the Turkish habitants in the areas where they had been resettled too.[50]

Grand vizier, 1917–1918

In 1917, Talaat became the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, a post equivalent to that of prime minister, but was unable to reverse the downward spiral of Ottoman fortunes in his new position.

Over the next year, Jerusalem and Baghdad were lost. On January 11, 1918, the special decree On Armenia was signed by Lenin and Stalin which rearmed and repatriated over 100,000 Armenians from the former Tsar's Army to be sent to the Caucasus for operations against Ottoman interests.[51][52] At the beginning of January 1918 with the Tsarist Army of the Caucasus departing, he had been influential in pursuing an offensive policy, convinced that despite all the pacifist rhetoric coming from Moscow 'the Russian leopard had not changed its spots'. The fall of Kars on 25 April 1918 reversed Russia's last conquest from the Berlin Treaty (1878) and Ottoman Turkey restored the 1877 borders against its Russian enemy. In October 1918 however, the British shattered both Ottoman armies they faced – and the armistice the British forced on Turkey at Mudros (30 October 1918) obliged the Ottoman army to evacuate Transcaucasia.[53] With defeat certain, Talaat had resigned on 14 October 1918.

Exile, 1919–1921

Talaat Pasha fled the Ottoman capital in a German submarine on 3 November 1918, from Constantinople harbour to Berlin. Just a week later the Ottoman Porte capitulated to the Allies and signed the Armistice of Mudros.

Public opinion was shocked by the departure of Talaat Pasha, even though he had been known to turn a blind eye on corrupt ministers appointed because of their associations with the CUP.[54] Talaat Pasha had a reputation for being courageous and patriotic, the type of individual who would willingly face the consequences of his actions.[54] With the occupation of Constantinople, Izzet Pasha resigned. Tevfik Pasha took the position of grand vizier the same day that British ships entered the Golden Horn. Tevfik Pasha lasted until 4 March 1919, replaced by Ferid Pasha whose first order was the arrest of leading members of the CUP.

Turkish courts-martial of 1919–1920

Following the occupation of Constantinople by the Allied Powers, the British exerted pressure on the Ottoman Porte and brought to trial the Ottoman leaders who had held positions of responsibility between 1914 and 1918 for having committed, among other charges, the Armenian Genocide. Those who were caught were put under arrest at the Bekirağa division and were subsequently exiled to Malta. The courts-martial were designed by Sultan Mehmed VI to punish the Committee of Union and Progress for the empire's ill-conceived involvement in World War I. The Pashas who had held the highest positions in the administration and whose names were at the top of the execution lists of the Armenian assassination teams could be condemned in absentia because they had gone abroad.

By January 1919, a report to Sultan Mehmed VI accused over 130 suspects, most of whom were high officials. The indictment accused the main defendants, including Talaat, of being "mired in an unending chain of bloodthirstiness, plunder and abuses". They were accused of deliberately engineering Turkey's entry into the war "by a recourse to a number of vile tricks and deceitful means". They were also accused of "the massacre and destruction of the Armenians" and of trying to "pile up fortunes for themselves" through "the pillage and plunder" of their possessions. The indictment alleged that "The massacre and destruction of the Armenians were the result of decisions by the Central Committee of Ittihadd".[55] The Court released its verdict on 5 July 1919: Talaat, Enver, Cemal, and Dr. Nazim were condemned to death in absentia.

The British were determined not to leave Talaat alone. The British had intelligence reports indicating that he had gone to Germany, and the British High Commissioner pressured Damad Ferit Pasha and the Sublime Porte to demand that Germany return him to the Ottoman Empire. As a result of efforts pursued personally by (Sir) Andrew Ryan, a former Dragoman and now a member of the British intelligence service, Germany responded to the Ottoman Empire stating that it was willing to be helpful if official papers could be produced showing these persons had been found guilty, and added that the presence of these persons in Germany could not as yet be ascertained.[56]

Aubrey Herbert interview, 1921

The last official interview Talaat granted was to Aubrey Herbert, a British intelligence agent.[57] It was nine days before his assassination. The interview was conducted during a series of short meetings in a park in a small German town. The interview gave chance to Talaat to explain the policies of the Ottoman Empire during the last 10 years.

These meetings corroborated earlier intelligence to the effect that Talaat Pasha was seeking support from Muslim countries to form a serious opposition movement against the Allied Powers, and that he was soon intending to take refuge in Ankara, where the Turkish national movement was forming. Furthermore, Talaat Pasha also threatened that he was going to incite the Pan-Turanist and Pan-Islamist movements against the United Kingdom unless it signed a peace treaty favorable for Turkey.

During this interview, Talaat maintained on several occasions that the CUP had always sought British friendship and advice, but that Britain was in no mood to offer any assistance whatsoever.[58]

Assassination, 1921

Before the assassination, the British intelligence services identified Talaat in Stockholm, where he had gone for a few days. The British intelligence first planned to apprehend him in Berlin, where he was planning to return, but then changed its mind because it feared the complications this would create in Germany. Another view in British intelligence was that Talaat should be apprehended by the Royal Navy at sea while returning from Scandinavia by ship. In the end, it was decided to let him return to Berlin, find out what he was trying to accomplish with his activities abroad, and to establish direct contact with him before giving the final verdict.[59] This was achieved with the help of Aubrey Herbert.

The British intelligence service established contact with its counterpart in the Soviet Union to evaluate the situation. Talaat Pasha's plans made the Russian officials as anxious as the British. The two intelligence services collaborated and signed between them the 'death warrant' of Talaat. Information concerning his physical description and his whereabouts was forwarded to their men in Germany.[59]

It was decided that Armenian revolutionaries should carry out the verdict.[59] Talaat was assassinated with a single bullet on 15 March 1921 as he came out of his house in Hardenbergstrasse, Charlottenburg. His assassin was an Armenian Revolutionary Federation member from Erzurum named Soghomon Tehlirian.[60] Soghomon Tehlirian admitted committing the shooting, but after a cursory two-day trial, he was found innocent by a German court on grounds of temporary insanity because of the traumatic experience he had gone through during the genocide.[61]

Legacy

Immediately following World War I

Talaat Pasha received widespread condemnation across the world for his leading role in the Armenian Genocide. He was found guilty of massacre of Armenians and sentenced to death in absentia by the Turkish Court on July 5, 1919.[62] Commenting on the widespread rape, torture and killings of the Armenians, U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Henry Morgenthau wrote in his 1919 memoir:

Whatever crimes the most perverted instincts of the human mind can devise, and whatever refinements of persecution and injustice the most debased imagination can conceive, became the daily misfortunes of this devoted people. I am confident that the whole history of the human race contains no such horrible episode as this. The great massacres and persecutions of the past seem almost insignificant when compared with the sufferings of the Armenian race in 1915.[63]

Post mortem

Shortly after the assassination of Talaat in March 1921, the "Posthumous Memoirs of Talaat" was published in the October volume of The New York Times Current History.[64] In his memoir, Talaat admitted to purposefully deporting the Armenians to the Ottoman Empire's eastern provinces in a prepared scheme. He however blamed Armenian civilians themselves for the deportations, implying the civilian population could have caused a revolution and it was therefore justified to exterminate them.[65][66]

He was buried in the Turkish Cemetery in Berlin. In 1943, his remains were taken to Istanbul and reburied in Şişli.[67]

Modern views

Talaat Pasha, Enver Pasha and Djemal Pasha are widely considered the main authors of the Armenian Genocide by historians.[68]

Historians have cited the influence of the Armenian Genocide on the Holocaust, which took place a few decades later. Records show the Nazis discussing and praising the Turkish model of extermination as early as the 1920s.[69]

Within modern Turkey, criticism also focuses on Talaat and the rest of the Three Pashas for causing the Ottoman Empire's entry into World War I and its subsequent partitioning by the Allies. Turkey's founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk widely criticized Talaat Pasha and his colleagues for their policies during and immediately prior to the First World War.[70]

A multitude of streets in Turkey display his name, as well as a street in the city of Paphos in the Republic of Cyprus that contains a large Turkish minority.[71]

In film

Talaat is depicted in two films:

See also

- The Remaining Documents of Talaat Pasha

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018). Talaat Pasha : father of modern Turkey, architect of genocide. Princeton University Press. p. 532. ISBN 978-0-691-15762-7.

References

Notes

- Original Turkish: 25–30 güne vasıl olmayan (İzzet Paşa) kabine(sin)deki yakın dönemdeki hizmetinde öğrendiğim bazı gizli şeyler vardır. Bu cümleden olmak üzere tuhaf bir şeye tesadüf ettim. Bu tehcir emri resmi olarak mahut Dahiliye Nazırı (Talat) tarafından verilmiş, vilayetlere tebliğ edilmiş. Bu resmi emri takiben ise çetelerin koşup melun vazifelerini yerine getirmeleri için Merkez-i Umumi (İttihat Terakki yönetimi) tarafından uğursuz emirler her yöne tamim (emir) olunmuştur. Binaenaleyh, çeteler meydan almış ve mukatale-i zalime (zalim katliam) yüz göstermiştir.

- Original Turkish: "Talat Bey'le temas ettim, imha emirlerini bizzat aldım. Memleketin selameti bundadır."

References

- Sylvia Kedourie, S Tanvir Wasti (1996) Turkey: Identity, Democracy, Politics. ISBN 0-7146-4718-7 p. 96

- Akçam, Taner (2006). A Shameful Act. New York: Holt & Co. pp. 165, 186–187.

- Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: Genocide and Extermination in World History from Carthage to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 414.

- Rosenbaum, Alan S. (2001). Is the Holocaust Unique?. Westview Press. pp. 122–123.

- Naimark, Norman (2001). Fires of hatred. Harvard University Press. p. 57.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas. Talaat Pasha Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide. Princeton University Press. p. xi. ISBN 9780691157627.

- Göçek, Fatma Müge (2015). Denial of violence : Ottoman past, Turkish present and collective violence against the Armenians, 1789–2009. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-19-933420-X.

- Auron, Yair (2000). The banality of indifference: Zionism & the Armenian genocide. Transaction. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7658-0881-3.

- Forsythe, David P. (11 August 2009). Encyclopedia of human rights (Google Books). Oxford University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9.

- Chalk, Frank Robert; Jonassohn, Kurt (10 September 1990). The history and sociology of genocide: analyses and case studies. Institut montréalais des études sur le génocide. Yale University Press. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-0-300-04446-1.

- Taner Timur, Türkler ve Ermeniler: 1915 ve Sonrası, İmge Kitabevi, 2001, ISBN 978-975-533-318-2, p. 53. (in Turkish)

- Abdullah I (King of Jordan), Philip Perceval Graves, Memoirs, publisher J. Cape, 1950, p. 40.

- Mango, Andrew (2004). Atatürk. London: John Murray. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7195-6592-2.

- Başverenler, başkaldıranlar at Google Books

- "İZ BIRAKAN PTT'CİLER (1) TALAT PAŞA | Telekomcular Derneği". www.telekomculardernegi.org.tr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Bjørnlund, Matthias (Fall 2006). "'When the Cannons Talk, the Diplomats Must be Silent' – A Danish diplomat in Constantinople during the Armenian genocide". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 1 (2): 197–223.

- Østrup, Johannes (1938). Erindringer (in Danish). H. Hirsch-sprungs forlag. p. 118.

- Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and soil a world history of genocide and extermination from Sparta to Darfur. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. pp. 404–5. ISBN 0300137931.

- Rae, Heather (2002). State identities and the homogenisation of peoples (1. publ. ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–4. ISBN 052179708X.

- Üngör, Ugur Ümit. The making of modern Turkey: nation and state in Eastern Anatolia, 1913–1950. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-965522-7.

- Peretz, Don (1994). The Middle East today. New York, NY: Praeger. p. 74. ISBN 0275945766.

- de Waal, Thomas (2015). Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019935071X.

- Jones, Adam (2010). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 1136937978.

- Gettleman, Marvin; Schaar, Stuart, eds. (2012). The Middle East and Islamic World Reader: An Historical Reader for the 21st Century (revised ed.). Grove/Atlantic, Inc. ISBN 0802194524.

- Steven L. Jacobs (2009). Confronting Genocide: Judaism, Christianity, Islam. Lexington Books. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-7391-3589-1.

On 24 April 1915 the Ministry of the Interior ordered the arrest of Armenian parliamentary deputies, former ministers, and some intellectuals. Thousands were arrested, including 2,345 in the capital, most of whom were subsequently executed ...

- Demourian, Avet (25 April 2009). "Armenians mark massacre anniversary". The Boston Globe.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). "Tehcir Law". In Whitehorn, Alan (ed.). The Armenian Genocide: The Essential Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1610696883.

- Josh Belzman (23 April 2006). "PBS effort to bridge controversy creates more". Today.com. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- "Exiled Armenians starve in the desert; Turks drive them like slaves, American committee hears ;- Treatment raises death rate". New York Times. 8 August 1916. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012.

- Hewitt, William L. (2004). Defining the horrific readings on genocide and Holocaust in the twentieth century. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 100. ISBN 013110084X.

- Bardakçı, Murat (2008). Talât Paşa'nın evrak-ı metrûkesi (in Turkish) (4. ed.). Cağaloğlu, İstanbul: Everest Yayınları. p. 211. ISBN 9752895603.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N. (2004). The history of the Armenian genocide : ethnic conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus (6th rev. ed.). New York: Berghahn Books. p. 384. ISBN 1-57181-666-6.

- Akçam, Taner (2006). "The Ottoman Documents and the Genocidal Policies of the Committee for Union and Progress (Ittihat ve Terakki) towards the Armenians in 1915". Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal. 1 (2): 140. ISSN 1911-0359.

- Akçam, Taner (2006). "The Ottoman Documents and the Genocidal Policies of the Committee for Union and Progress (Ittihat ve Terakki) towards the Armenians in 1915". Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal. 1 (2): 142–3. ISSN 1911-0359.

- Anderson, Perry (2011). The new old world (pbk. ed.). London: Verso. p. 459. ISBN 978-1-84467-721-4.

Resit Bey, the butcher of Diyarbakir

- Olaf Farschid, ed. (2006). The first world war as remembered in the countries of the eastern mediterranean. Würzburg: Ergon-Verl. p. 52. ISBN 3899135148.

Later, Reshid became infamous for organizing the extermination of the Armenians in the province of Diarbekir, receiving the nickname "Kasap" (the butcher)

- Gaunt, David (2006). Massacres, resistance, protectors: muslim-christian relations in Eastern Anatolia during world war I (1st Gorgias Press ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias. p. 157. ISBN 1593333013.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N.; Akçam, Taner (2011). Judgment at Istanbul the Armenian genocide trials. New York: Berghahn Books. p. 86. ISBN 085745286X.

- Wolcott, Martin Gilman; The Evil 100 (2000); Page 350; Citadel Press

- Dadrian, Vahakn (1989). "Genocide as a Problem of National and International Law: The World War I Armenian Case and Its Contemporary Legal Ramifications". Yale Journal of International Law. 14 (2): 258. ISSN 0889-7743. OCLC 12626339.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N. (2004). The history of the Armenian genocide: ethnic conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus (6th rev. ed.). New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 1571816666.

- A., Bernstorff (2011). Memoirs of Count Bernstorff. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-169-93525-7.

- Travis, Hannibal (2010). Genocide in the Middle East: the Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, N.C.: Carolina Academic Press. p. 219. ISBN 1594604363.

- Avedian, Vahagn. "The Armenian Genocide 1915 From a Neutral Small State's Perspective: Sweden" (PDF). Historiska institutionen Uppsala universitet. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Morgenthau, Sr., Henry (1919). Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. Doubleday, Page. p. 342.

- Morgenthau, Sr., Henry (1919). Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. Doubleday, Page. p. 336.

- Morgenthau, Sr., Henry (1919). Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. Doubleday, Page. p. 339.

'I wish,' Talaat now said, 'that you would get the American life insurance companies to send us a complete list of their Armenian policy holders. They are practically all dead now and have left no heirs to collect the money. It of course all escheats to the State. The Government is the beneficiary now. Will you do so?'

This was almost too much, and I lost my temper.

'You will get no such list from me,' I said, and I got up and left him. - Memoirs of Halide Edip by Halide Edip, The Century Company, NY, 1926, p. 387, at Google Books

- Najmuddin; Najmuddin, Dilshad; Shahzad (2006). Armenia: A Resume with Notes on Seth's Armenians in India. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4669-5461-2.

- Üngör, Umut. "Young Turk social engineering : mass violence and the nation state in eastern Turkey, 1913- 1950" (PDF). University of Amsterdam. pp. 217–226. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- McMeekin, Sean (2010). The Berlin-Baghdad Express: Ottoman Empire and Germany's bid for World Power. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674057395.

- Reynolds, Michael A. (May 2009). "Buffers, not Brethren: Young Turk Military Policy in the First World War and the Myth of Panturanism". 2003. Past and Present. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sean Mcmeekin, The Berlin-Baghdad Express, p.330,337

- Kedourie, Sylvia (1996). Turkey: Identity, Democracy, Politics. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 0-7146-4718-7.

- V. Dadrian, The History of the Armenian Genocide, pp. 323-324.

- Oke, Mim Kemal (1988). The Armenian question 1914–1923. Nicosia: Oxford 1988, ataa.org

- Herbert, Aubrey (1925). Ben Kendim: A Record of Eastern Travel. G. P. Putnam's sons ltd. p. 41. ISBN 0-7146-4718-7.

- Kedourie, Sylvia (1996). Turkey: Identity, Democracy, Politics. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 0-7146-4718-7.

- Oke, Mim Kemal (1988). The Armenian question 1914–1923. Rustem & Brother. ISBN 978-9963-565-16-0.

- Operationnemesis.com

- "Robert Fisk: My conversation with the son of Soghomon Tehlirian". The Independent. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- Dadrian, Vahakn, "The History of the Armenian Genocide", Page 323-324, Berghahn Books, 2003

- "Henry Morgenthau, Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, Page 119, Blackmask Online" (PDF). Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Talaat Pasha, "Posthumous Memoirs of Talaat Pasha", The New York Times Current History, Vol. 15, no. 1 (October 1921): 295

- "I admit that we deported Armenians from our eastern provinces, and we acted in this matter upon a previously prepared scheme. The responsibility of these acts falls upon the deported people themselves. Russians ... had armed and equipped the Armenian inhabitants of this district [Van] ... and had organized strong Armenian bandit forces. ... When we entered the Great War, these bandits began their destructive activities in the rear of the Turkish army on the Caucasus front, blowing up the bridges and killing the innocent Mohammedan inhabitants regardless of age and sex... All these Armenian bandits were helped by the native Armenians." Hovannisian, Richard; The Armenian Genocide in Perspective, Page 142, Transaction Publishers, 1987

- ""Naturally the Christians became alarmed when placards were posted in the villages and cities ordering everybody to bring their arms to headquarters. Although this order applied to all citizens, the Armenians well understood what the result would be, should they be left defenseless while their Moslem neighbours were permitted to retain their arms. In many cases, however, the persecuted people patiently obeyed the command; and then the Turkish officials almost joyfully seized their rifles as evidence that a "revolution" was being planned and threw their victims into prison on a charge of treason. Thousands failed to deliver arms simply because they had none to deliver, while an even greater number tenaciously refused to give them up, not because they were plotting an uprising, but because they proposed to defend their own lives and their women's honour against the outrages which they knew were being planned. The punishment inflicted upon these recalcitrants forms one of the most hideous chapters of modern history. Most of us believe that torture has long ceased to be an administrative and judicial measure, yet I do not believe that the darkest ages ever presented scenes more horrible than those which now took place all over Turkey." Henry Morgenthau, Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, Page 112, Blackmask Online" (PDF). Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "Talât Pascha (1872 - 1921) - Find A Grave Memorial". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- Alayaria, Aida; Consequences of Denial: The Armenian Genocide, Page 182, 2008, Karnac Books Ltd

- "In the German interwar and Nazi discourses on the New Turkey, one finds a chilling propagation of what a post-genocidal country, one cleansed of its minorities, could achieve: To the Nazis, the New Turkey was something of a post-genocidal wonderland, something that Germany would have to emulate. The Nazis were discussing the Turkish model already in the early 1920s. A German-Jewish newspaper reader and critic of Anti-Semitism, Siegfried Lichtenstaedter, understood the "Turkish lessons" formulated in Nazi articles (in 1923 and 1924) to mean that the Jews of Germany and Austria should be, and had to be, killed and their property given to "Aryans.""; Ihrig, Stefan; How the Armenian Genocide Shaped the Holocaust; 2016

- Muammer Kaylan. The Kemalists: Islamic Revival and the Fate of Secular Turkey. Prometheus Books, Publishers. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-61592-897-2.

- "Talat Paşa". Talat Paşa. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Talaat Pasha. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Talaat Pasha |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mehmed Talat |

- First World War.com: Talat Pasha's Alleged Orders Regarding the Armenian Massacres

- Interview with Talaat Pasha by Henry Morgenthau – American Ambassador to Constantinople 1915

- Talaat Pasha's report on the Armenian Genocide

- Mehmet Talaat (1874–1921) and his role in the Greek Genocide

- Newspaper clippings about Talaat Pasha in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by |

Minister of Interior 4 February 1917 – 23 January 1913 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by Mehmet Cavit Bey |

Minister of Finance November 1914 – 4 February 1917 |

Succeeded by Abdurrahman Vefik Sayın |

| Preceded by Said Halim Pasha |

Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire 4 February 1917 – 8 October 1918 |

Succeeded by Ahmed Izzet Pasha |