Effects of genocide on youth

The effects of genocide on youth include psychological and demographic effects that affect the transition into adulthood. These effects are also seen in future generations of youth.

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

| Issues |

| Genocide of indigenous peoples |

|

| Late Ottoman genocides |

| World War II (1941–1945) |

| Cold War |

|

| Genocides in postcolonial Africa |

|

| Ethno-religious genocide in contemporary era |

|

| Related topics |

| Category |

Demographic effects involve the transfer of children during genocides. In cases of transfer, children are moved or displaced from their homes into boarding schools, adoptive families, or to new countries with or without their families. There are significant shifts in populations in the countries that experience these genocides. Often, children are then stripped of their cultural identity and assimilated into the culture that they have been placed into.

Unresolved trauma of genocide affects future generations of youth.[1] Intergenerational effects help explain the background of these children and analyze how these experiences shape their futures. Effects include the atmosphere of the household they grew up in, pressures to succeed or act in specific ways, and how they view the world in which they live.

The passing down of narratives and stories are what form present day perceptions of the past.[2] Narratives are what form future generations' ideas of the people who were either victimized or carried out the genocide. As youth of future generations process the stories they hear they create their own perception of it and begin to identify with a specific group in the story. Youth of future generations begin to form their identity through the narratives they hear as they begin to relate to it and see how the genocide affects them. As stories are passed down, children also begin to understand what their parents or grandparents went through. They use narratives as explanation of why their parents talk about it in the way they do or do not talk about it all.[3]

Psychological effects of genocide are also relevant in youth. Youth who experience an extreme trauma at an early age are often incapable of fully understanding the event that took place. As this generation of children transition into adulthood, they sort out the event and recognize the psychological effects of the genocide. It is typical for these young survivors to experience symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as other psychological disorders.

Transitioning out of youth and into adulthood is an important development marker in the lives of all people. Youth who transition into adulthood during a genocide have a different experience than those who do not transition during a genocide. Some youth transition earlier as means of survival. Others are unable to fully transition, remaining in a youth state longer.

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States were subject to military and land-taking campaigns by U.S. government policies. Disease reduced 95 percent the American Indian population between 1492 and 1900, the worst demographic collapse in human history. There were also frequent violent conflicts between Indians and settlers.[4] Scholarly debates have not resolved whether specific conflicts during US military expansion can be defined as genocide because of questions over the intent.[5] Specific conflicts such as the Sand Creek massacre, the 1851 California Round Valley Wars, and Shoshoni massacres in the 1860s in Idaho have been described as genocidal or genocide.[6] Cultural genocide included the intent to destroy cultural systems like collective land ownership and preventing children from learning the Native culture.[1]

Youth and children were included among non-combatants killed by military forces, vigilantes, or disease during US colonization. Cases of girls being raped and children being cut into pieces were documented in the states of Arizona, Ohio, and Wyoming in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[6] Children were taken prisoner after battles between whites and Native Americans.[7]

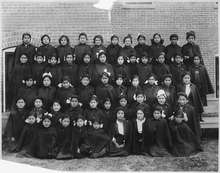

Youth in boarding schools

Youth were a primary target for many state projects. From 1824 until the 1970s, approximately 100 boarding schools were operated by the United States federal government.[8] Native families volunteered and were forced to send their children to attend Indian Boarding Schools. it has been claimed that this state intention was to keep youth from learning indigenous culture: one boarding school founder described boarding schools as a way to "Kill the Indian, Save the Man."[6] Children at these sites experienced physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. However, oral histories also document that youth had good experiences of friendships, skills learned, and sporting events.[9] As adults, they often struggled to raise their own children when returning to Indian cultural contexts.[1]

Intergenerational effects

Brave Heart and DeBruyn, psychologists treating American Indian youth, compare psychological trauma caused by massacres, land allotment, and boarding schools to the trauma experienced by Holocaust survivor descendants.[1] Adults who experienced boarding schools as children seek treatment to be able to adequately bond with their children. American Indian groups have created treatment processes such as the Takini Network: Lakota Holocaust Survivors' Association to treat youth and adults through cultural competence, participation in traditional ceremonies, and grief management.[1]

Armenian genocide, Turkey

The Armenian genocide began in 1915 when the Turkish government planned to wipe out Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire. About 2 million Armenians were killed and many more were removed from the country by force. The Turkish government does not acknowledge the events of the Armenian genocide as genocide.[10]

Demographic effects

The biggest demographic shift is the number of children that were internally displaced within the Ottoman Empire. During the Armenian genocide, at least 60,000 youth were transferred to many different locations. Children were taken from their homes and transferred to poorly supplied camps where they would be sold. Some children were sold to central Anatolia to wealthy households for education and assimilation into the Turkish culture. Other children were sold to Muslim villagers who would then receive a stipend each month for raising them. In these instances, the displaced children had typically better lives than what they would have had with Armenian parents. Not all went to these types of homes. Some youth were sold for circumstances of exploitation and unpaid hard labor. Other youth were sent to homes in which they experienced physical and sexual abuse. Some young people were placed in homes of the people who were responsible for their parents' deaths. No matter what type of home they were sent to, the transfer of children involved the stripping of their culture identity. Their Armenian culture was erased by being raised in non-Armenian households; the Turkish government was carrying out a cultural genocide.[11]

Intergenerational effects

Narratives of the stories of the genocide are passed down from generation to generation in order for the story to continue to live on. It allowed the children of future generations to find their sense of ethnic identity through it. There are many different aspects of life in which children begin to form their identity, and in the Armenian culture, an emphasis is placed on the children to identify with the Armenian culture. Though the events of the Armenian genocide are historical facts, the personal stories from witnesses are used as a cultural artifact in the lives of Armenian children. They grow up with this strong sense of belonging to this culture due to these stories of suffering and use them as a uniting force.[2] Armenians are united in this ethnic community, known as the Armenian diaspora. Whether they are Russian or Armenian-Americans, they are part of the Armenian diaspora.[12] The desire for future generations to actively be part of this Armenian diaspora stems from the primary generation and their experiences with the cultural genocide.[11]

Future generations of genocide survivors recognize the shift in their geographical location due to the genocide. Future generations of Armenian-Americans have been told and retold the stories of how their ancestors came to America, and they recognize that if it had not been for the Armenian genocide, they might not be where they are today. They see the effect of the genocide in that they might still be in Armenia.[2] Future generations of children that are born in Russia recognize that their geographical location within Russia was effected by the genocide. They feel at home in places such as Krasnodar, Russia because that is where their families have migrated to after the genocide. Although the future generations of Armenian genocide survivors have migrated all over the globe and made their homes in these places, their ancestors have instilled a love for Armenia, the historic homeland.[12]

Cambodian genocide, Cambodia

The Cambodian genocide began in 1975 when Pol Pot, a Khmer Rouge leader, attempted to build a Communist peasant farming society. About 1.5 million Cambodians died.[13]

Demographic effects

Many Cambodian youth were taken to Canada in the 1980s. Most came through private sponsorship programs or through the Canadian federal government as refugees. Many of these sponsorship programs were Christian organizations through the "Master Agreement" made with the Canadian government. Primarily, families became refugees in Montreal and Toronto. Other small groups of refugees went to Ottawa, Hamilton, London, and Vancouver. Most refugees were of the lowest economic class in Cambodia, and they had less education. An emphasis was placed on getting the children refugees caught up academically with their peers of the same age by sending them to school. Cambodian Canadians preferred to stay in bigger cities such as Toronto because it allowed the children to attend school together. In these areas where the Cambodian population was higher, racism in schools against Cambodian refugees was less evident. Though they were placed in Canada, there was still a stress to maintain Khmer culture. Many parents continued to speak Khmer to their children, keeping the language alive. Khmer décor was hung in homes and Khmer traditions were carried out within the homes as a way to raise the children in Khmer culture.[14]

Intergenerational effects

Many second and third generation youth of survivors of the Cambodian genocide recognize the stories they are told as their primary source of information. The stories they hear discuss the Khmer Rouge in a negative way. Survivor stories include talk about harsh living and working conditions in which they were separated from their families, starved, tortured, and even killed. Other households avoid the subject all together. Some survivors do not want to relive the old traumas so they keep silent. Other survivors cannot make sense of it and do not want to be subject to the questions of youth that they cannot answer.[3]

Many youth in the generations following the genocide experience broken home life. They live in homes controlled by parents with PTSD. The youth experience their parents' hyper arousal, intrusive recollection, traumatic amnesia, and being easily frightened.[3][15] Even if the parents do not have PTSD, they still often elicit behaviors of emotional unavailability, over protection, and poor parenting on their children. Some children of survivors experience violence in their home such as physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect. Children in the following generations who have been raised in violent homes because of their parents' experiences have often elicited violent behaviors. School shootings, stabbings, and knifings have become more common among Cambodians following the genocide.[15] Some youth believe that it is because of the Khmer Rouge and the Cambodian genocide that they suffer from economic hardships.[3]

In schools following the events of the Cambodian genocide, youth received mixed interpretations of the events of the genocide. Information about the time period in which these events occurred, known as the Democratic Kampuchea, was severely limited or even taken out of textbooks. Children previously participated in Hate Day, a day in which they were taught to hate Pol Pot and disapprove of the Khmer Rouge. Now, the day has become known as the Day of Remembrance in which they remember those who lost their lives during this time.[3]

It was not just the following generations of the survivors that were affected by the genocide, but the youth of the Khmer Rouge as well. Most youth with parents who were members of the Khmer Rouge do not hear of the events from their parents, but rather find information from museums, neighbors, and friends. Once they find out the cruelty that their parents and grandparents exhibited, they often feel embarrassed and do not want to identify themselves as children of the Khmer Rouge. Many Khmer Rouge members are ashamed and fear ostracism from their peers.[3]

Psychological effects

Cambodian youth who had been a part of the Cambodian genocide experienced high levels of violence early on in their lives. Many youth survivors have shown symptoms of PTSD. The amount of Cambodian genocide survivors with PTSD is five times higher than the average in the United States. Many survivors also experience panic disorder.[16]

There are children who survived the Cambodian genocide that may not have experienced the genocide directly, yet they still experienced psychological effects of the genocide through their parents. Parents often elicited anger towards their children following the Cambodian genocide. This anger was frequent and the episodes met the criteria for a panic-attack. When this anger was elicited within the home, trauma recall among the parent and the child was often triggered, resulting in catastrophic cognitions.[16]

Groups of Cambodian refugees often fled to highly populated areas in the country in which they fled to. Within these countries, they often resided in poorer areas of the city, which were considered high violence areas. Youth who experienced high violence in Cambodia and then moved to high violence areas in other countries are at greater risk for developing PTSD.[17]

Transition to adulthood

Military agrarianism was stressed under the Khmer Rouge, meaning young people were expected to be peasants and soldiers as part of the war effort. Prior to this time of war, youth was defined as a time free from responsibilities, typically ages seven to twenty-one. At the end of this time, youth would transition into adulthood via getting a job, having a family, and gaining responsibility. As youth became a part of the war effort, this transition was delayed. Youth were not able to transition into adulthood until almost age thirty. Instead of gaining more responsibility, youth stayed in a time of which they were disciplined, controlled, and homogenized by military leaders.[18]

Some child victims of the genocide who were able to escape the Khmer Rouge and flee to other countries were able to stay on track with their transition into adulthood. Many children were put in schools right away in order to keep them on the same academic level as their peers. Parents encouraged children to finish school, find work, and pursue family life in the same manner as their peers.[14]

Holocaust, Germany

The Holocaust began in 1933 prior to World War II in Germany when the Nazi regime under Adolf Hitler's rule attempted to wipe out the "inferior" people of the country. This primarily included people of the Jewish culture, but also included Gypsies, the disabled, some Slavic people, Jehovah's Witnesses, and homosexuals. By the end of the Holocaust in 1945, more than 6 million Jewish people had been killed.[19] Of these 6 million that had been killed, 1.5 million were children between ages zero and eighteen. By killing off many Jewish children, the Nazi regime hoped to exterminate the core and root of the Jewish culture.[20]

Demographic effects

Following the Holocaust, many survivors in Europe became displaced persons. Younger survivors had grown up inside concentration camps, Jewish ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe or in hiding. The destruction of murdered family and community and continuing hatred and violence against Jews often made return to their hometowns impossible. Many survivors went to European territories that were under the rule of the Allies of World War II. Some survivors went legally or illegally to British Mandatory Palestine. Many displaced persons went to the State of Israel, established in May 1948. Quota restrictions on immigration to the United States were gradually loosened, allowing many Holocaust survivors to immigrate to the United States where they were provided with US immigration visas for displaced persons under the Displaced Persons Act. Other destinations included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, South America, and South Africa.[21]

Intergenerational effects

Survivors of the Holocaust lived through very traumatic experiences, and their children and grandchildren felt the repercussions of this trauma. Generations following the Holocaust learned to have a distrust of the world. They were taught that the world and the people in it were inherently bad and could not be trusted, producing an ever-present fear of danger. Parents gave youth a terrifying worldview by failing to provide an effective framework of security and stability.[22] Parents viewed the world as inherently bad, and they often inflicted overprotectiveness on their children. Children of survivors of the Holocaust grew up with many restrictions to their daily lives as parents took on controlling roles in order to protect their children from the outside world.[23][24]

Survivors of the Holocaust received little to no education while in the concentration camps. They lost all opportunity to advance academically. Children of survivors feel the repercussions of the Holocaust by the parents' constant pressure for them to achieve academically.[22] The role of the child within the family was to provide hope for the future, creating a sense of over involvement of the parents in the children's lives. Children viewed their parents as living vicariously through them; the parents were stripped of a childhood experience and must experience it through their own children.[24] Due to the lack of education, survivors sometimes lacked communication skills. The communication skills they passed on to their children could be affected. An inability to communicate feelings was impressed on children when they were never taught the proper way to do so. The communication that occurred within the home also reflected the knowledge of the Holocaust events that were passed down to further generations. Some parents who survived the Holocaust were very vocal about the events, providing accurate stories to their children to allow the survivor to present the traumatic experience without becoming distant from it. Other parents did not directly recount their traumatic experiences to their children, rather young people became aware of the experiences through hearing the conversations their parents had with others. Some parents did not talk about it at all; they did not want to remember it, were afraid of remembering it, and ashamed of remembering it because of how traumatic the experiences were.[22]

Second and third generations of Holocaust survivors have also inherited PTSD symptoms. Because their parents or grandparents have developed such severe PTSD, youth in the following generations have a predisposition to developing PTSD.[22][23] This predisposition could have been due to the way they were raised. Second and third generations of survivors could also experience subsequent childhood traumas inflicted from their parents or grandparents. Depression in parent survivors is very prevalent, and children of these survivors are more vulnerable to developing depression as well. Behavior disorders were also more prevalent in children of survivors of the Holocaust.[22]

Psychological effects

Youth that grew up as victims of the Holocaust also experienced many psychological effects. One effect was that of learned helplessness. They grew up believing that they were inferior to everyone else, creating a victim mindset. They also had inherent feelings of abandonment, loneliness, and a sense of being unwanted. Being separated from their parents, separated from everyone they knew, they grew up thinking that everyone left them. Being constantly moved around they were not able to make concrete relationships and became lonely. Youth were raised in concentration camps where if they were not valuable they would be exterminated; proving themselves was used as a survival tactic. The feeling of needing to prove themselves carried over in every day life even as the war ended and they were no longer victims of the Holocaust. As another means of survival, children often had to alter their identities. They rid themselves of Jewish names and tendencies in order to survive.[24] During the Holocaust they grew up believing that they should be ashamed of who they were and their identity.[20] When the war ended, they struggled with returning to their Jewish life. Youth questioned who they were and struggled with finding their identity.[24]

Many young people that experienced the Holocaust became suicidal. They lost the desire to exist or felt a deep disgust at the idea of living. Germans questioned why Jews in the ghettos did not commit mass suicide because of how hard the Germans had made life for the Jews. Some youth survivors used the Nazi domination to fuel their desire to live and desire to fight back.[20]

Transition to adulthood

Youth who experienced the Holocaust at an early age were consequently stripped of their childhood in that they were prevented from having a normal childhood. They were forced to transition into adulthood much more quickly than those who were not victims of this genocide. As children, they had to be adults because it was dangerous to be a child. Children were often targeted groups of people to be exterminated during the Holocaust due to the fact that they could not help the Nazi regime. Young people had to prove themselves beneficial in order to survive, which for them meant becoming adults early on in age. Children survivors have grown up and created an alter ego child who desires to live the childish life that they missed out on due to the Holocaust.[24]

Some youth transitioned into adulthood in that they became very future oriented and determined to plan for the future. They planned on how they would continue on life after the Holocaust. Their goal was to live in a manner much like how they had lived before the genocide began. They also talked about achieving more than their parents ever had. Some youth talked about travel and studying abroad, becoming well versed in other languages and cultures. Youth were forced to focus on the future and plan for it rather than dwell in the youth years and childish lifestyle.[20]

See also

- Acute stress reaction

- Chronic stress

- Combat stress reaction

- Compassion fatigue

- Complex posttraumatic stress disorder

- Da Costa's syndrome

- Emotional dysregulation

- Malingering of posttraumatic stress disorder

- Posttraumatic embitterment disorder

- Psychogenic amnesia

- Psychoneuroimmunology

- PTSD Symptom Scale – Self-Report Version

- Research on the effects of violence in mass media

- Shell shock

- Survivor syndrome

- Susto

- Symptoms of victimization

- Thousand-yard stare

- Trauma model of mental disorders

References

- Brave Heart, Maria Y.H.; DeBruyn, Lemyra. "The American Indian: Holocaust: Healing Historical Unresolved Grief" (PDF). MN Department of Human Services. MCWTS. pp. 1–14.

- Azarian-Ceccato, Natasha (2010). "Reverberations of the Armenian Genocide: Narrative's intergenerational transmission and the task of not forgetting". Narrative Inquiry. 20 (1): 106–123. doi:10.1075/ni.20.1.06aza.

- Münyas, Burcu (September 2008). "Genocide in the minds of Cambodian youth: transmitting (hi)stories of genocide to second and third generations in Cambodia". Journal of Genocide Research. 10 (3): 413–439. doi:10.1080/14623520802305768.

- Jackson, Robert (2011). "Demographics, Historical". In Tucker, Spencer (ed.). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8.

- Rensink, Brenden (2011). Genocide of Native Americans: Historical Facts and Historiographic Debates. Lincoln, NE: Digital Commons. pp. 18–22.

- Lamm, Alan (2011). "Demographics, Historical". In Tucker, Spencer (ed.). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8.

- Pierpaoli Jr., Paul (2011). "Demographics, Historical". In Tucker, Spencer (ed.). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 471. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8.

- "American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many". NPR.org. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- "Native Words Native Warriors". americanindian.si.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- "Armenian Genocide". History.com. A+E Networks. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- Watenpaugh, Keith David (July 2013). ""Are There Any Children for Sale?": Genocide and the Transfer of Armenian Children (1915–1922)". Journal of Human Rights. 12 (3): 283–295. doi:10.1080/14754835.2013.812410.

- Ziemer, Ulrike (May 2009). "Narratives of Translocation, Dislocation and Location: Armenian Youth Cultural Identities in Southern Russia". Europe-Asia Studies. 61 (3): 409–433. doi:10.1080/09668130902753283.

- "Pol Pot". History.com. A+E Networks. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- McLellan, Janet (2009). Cambodian refugees in Ontario : resettlement, religion, and identity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9962-4.

- Chung, Margaret. "Intergenerational Effects of Genocidal Disaster among Cambodian Youth". National Association of Social Workers, New York City Chapter. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- Hinton, Devon E.; Rasmussen, Andrew; Nou, Leakhena; Pollack, Mark H.; Good, Mary-Jo (November 2009). "Anger, PTSD, and the nuclear family: A study of Cambodian refugees". Social Science & Medicine. 69 (9): 1387–1394. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.018. PMC 2763362. PMID 19748169.

- Berthold, S. Megan (July 1999). "The effects of exposure to community violence on Khmer refugee adolescents". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 12 (3): 455–471. doi:10.1023/A:1024715003442. PMID 10467555.

- Raffin, Anne (September 2012). "Youth Mobilization and Ideology". Critical Asian Studies. 44 (3): 391–418. doi:10.1080/14672715.2012.711977.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. "Introduction to the Holocaust". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- Clark, Joanna (1999). Holocaust Youth and Creativity. Educational Resources Information Center. pp. 1–55.

- "The Aftermath of the Holocaust". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. August 18, 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Braga, Luciana L; Mello, Marcelo F; Fiks, José P (2012). "Transgenerational transmission of trauma and resilience: a qualitative study with Brazilian offspring of Holocaust survivors". BMC Psychiatry. 12 (1): 134. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-134. PMC 3500267. PMID 22943578.

- Barel, Efrat; Van IJzendoorn, Marinus H.; Sagi-Schwartz, Abraham; Bakermans-Kranenburg, Marian J. (2010). "Surviving the Holocaust: A meta-analysis of the long-term sequelae of a genocide". Psychological Bulletin. 136 (5): 677–698. doi:10.1037/a0020339. PMID 20804233.

- Kellermann, Natan P.F. (7 January 2011). "The Long-Term Psychological Effects and Treatment of Holocaust Trauma". Journal of Loss and Trauma. 6 (3): 197–218. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.623.9640. doi:10.1080/108114401753201660.

External links