Western Armenia

Western Armenia (Western Armenian: Արեւմտեան Հայաստան, Arevmdian Hayasdan), located in Western Asia, is a term used to refer to eastern parts of Turkey (formerly the Ottoman Empire) that were part of the historical homeland of the Armenians.[2] Western Armenia, also referred to as Byzantine Armenia, emerged following the division of Greater Armenia between the Byzantine Empire (Western Armenia) and Sassanid Persia (Eastern Armenia) in 387 AD.

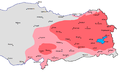

Orange: areas overwhelmingly populated by Armenians (Republic of Armenia: 98%;[1] Nagorno-Karabakh: 99%; Javakheti: 95%)

Yellow: Historically Armenian areas with presently no or insignificant Armenian population (Western Armenia and Nakhichevan)

The area was conquered by the Ottomans in the 16th century during the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555) against their Iranian Safavid arch-rivals. Being passed on from the former to the latter, Ottoman rule over the region became only decisive after the Ottoman–Safavid War of 1623–1639.[3] The area then became known as Turkish Armenia or Ottoman Armenia. During the 19th century, the Russian Empire conquered all of Eastern Armenia from Iran,[4] and also some parts of Turkish Armenia, such as Kars. The region's Armenian population was affected during the widespread massacres of Armenians in the 1890s.

The Armenians living in their ancestral lands were exterminated or deported by Ottoman forces during the 1915 Armenian Genocide and over the following years. The systematic destruction of Armenian cultural heritage, which had endured over 4000 years,[5][6] is considered an example of cultural genocide.[7][8]

Only assimilated and crypto-Armenians live in the area today, and some irredentist Armenians claim it as part of United Armenia. The most notable political party with these views is the Armenian Revolutionary Federation.

Etymology

In the Armenian language, there are several names for the region. Today, the most common is Arevmtyan Hayastan (Արևմտյան Հայաստան) in Eastern Armenian (mostly spoken in Armenia, Russia, Georgia, Iran) and Arevmdean Hayasdan (Արեւմտեան Հայաստան) in Western Armenian (spoken in the Diaspora: US, France, Lebanon, Syria, Argentina, etc.). Archaic names (used before the 1920s) include Tačkahayastan (Տաճկահայաստան) in Eastern and Daǰkahayasdan in Western Armenian. Also used in the same period were T'urk'ahayastan (Թուրքահայաստան) or T'rk'ahayastan (Թրքահայաստան), both meaning Turkish Armenia.

In the Turkish language, the literal translation of Western Armenia is Batı Ermenistan. The region has been officially described as Eastern Anatolia (Doğu Anadolu) since the seven geographical regions of Turkey were defined at the 1941 First Geography Congress. Throughout much of recorded history the eastern boundary of Anatolia was not considered to extend as far as the Araxes, the river which marks the present day boundary between the states of Armenia and Iran.[12] Some Kurds refer to the southern parts of region as Bakurê Kurdistanê (Northern Kurdistan).

History

Ottoman conquest

After the Ottoman-Persian War (1623–1639), Western Armenia became decisively part of the Ottoman Empire.[13] Since the Russo-Turkish War, 1828–1829, the term "Western Armenia" has referred to the Armenian-populated historical regions of the Ottoman Empire that remained under Ottoman rule after the eastern part of Armenia was ceded to the Russian Empire by the Qajar Persians following the outcome of the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813) and Russo-Persian War (1826–1828).[14]

Western (Ottoman) Armenia consisted of six vilayets (vilâyat-ı sitte): the vilayets of Erzurum, Van, Bitlis, Diyarbekir, Kharput, and Sivas.[15]

The fate of Western Armenia – commonly referred to as "The Armenian Question" – is considered a key issue in the modern history of the Armenian people.[16]

World War I and later years

Armenian Genocide

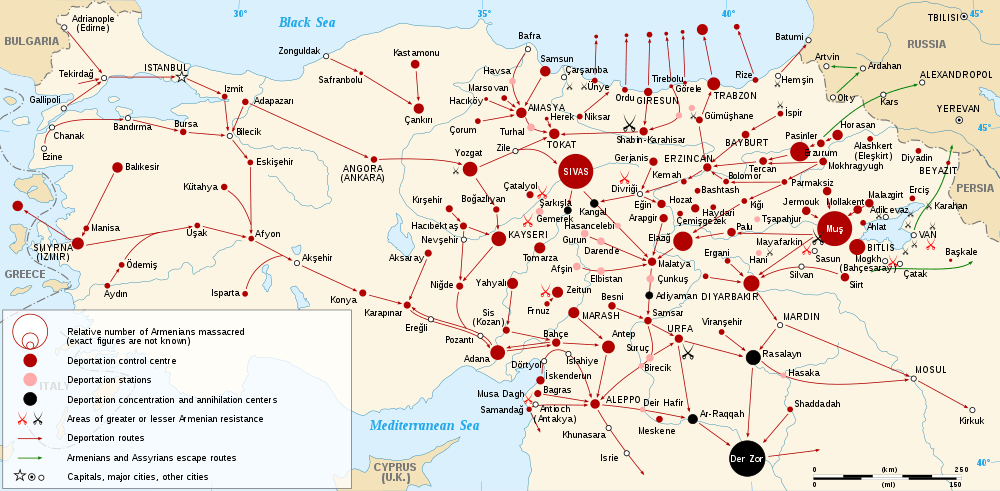

In 1894–1896 and 1915 the Ottoman Empire perpetrated systematic massacres and forced deportations of Armenians[17] resulting in the Armenian Genocide. The massive deportation and killings of Armenians began in the spring 1915. On 24 April 1915, Armenian intellectuals and community leaders were deported from Constantinople. Depending on the sources cited, about 1,500,000 Armenians were killed during this act.

Caucasus Campaign

During the Caucasus Campaign of World War I, the Russian Empire occupied most of the Armenian-populated regions of the Ottoman Empire. A temporary provincial government was established in occupied areas between 1915 and 1918.

The chaos caused by the Russian Revolution of 1917 put a stop to all Russian military operations and Russian forces began to conduct withdrawals. The first and second congresses of Western Armenians took place in Yerevan in 1917 and 1919.

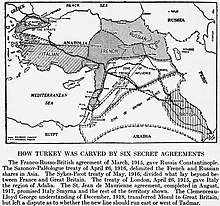

Sazonov–Paléologue Agreement

The Sazonov–Paléologue Agreement of 26 April 1916 between Russian Foreign minister Sergey Sazonov and French ambassador to Russia Maurice Paléologue proposed to give Western Armenia to Russia in return for Russian assent to the Sykes–Picot agreement.[18][19]

Current situation

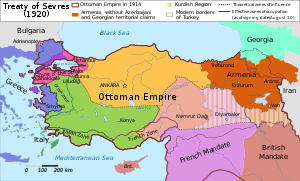

Currently, Armenia does not have any territorial claims against Turkey, although one political party, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, the largest Armenian party in the diaspora, claims the area given to the Republic of Armenia (1918–1920) by US President Woodrow Wilson's arbitral award as part of the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, also known as Wilsonian Armenia.

Since 2000, an organizing committee of the congress of heirs of Western Armenians who survived the Armenian Genocide is active in diasporan communities.[20]

Territories claimed

| Area | Part of | Area (km²) | Population | Armenians | % Armenian | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Armenia | 132,967 | 6,461,400 | N/A | 2009 estimate[21] | ||

Gallery

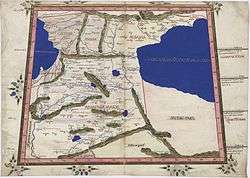

Western Armenia the first half of the 18th century. Herman Moll's map,1736.

Western Armenia the first half of the 18th century. Herman Moll's map,1736. Armenia Turkomania on 1810 map.

Armenia Turkomania on 1810 map..jpg) Persis, Parthia, Armenia. Rest Fenner, published in 1835.

Persis, Parthia, Armenia. Rest Fenner, published in 1835. The Six Armenian vilayets (provinces) of the Ottoman Empire were defined as Western Armenia.

The Six Armenian vilayets (provinces) of the Ottoman Empire were defined as Western Armenia. Armenian Genocide: map of massacre locations and deportation and extermination centers.

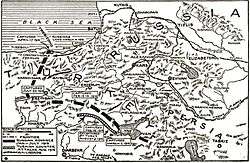

Armenian Genocide: map of massacre locations and deportation and extermination centers. The area of Russian occupation of Western Armenia in summer 1916 (Russian map).

The area of Russian occupation of Western Armenia in summer 1916 (Russian map). The area of Russian occupation of that region in summer 1916.

The area of Russian occupation of that region in summer 1916. The modern concept of United Armenia as used by Woodrow Wilson and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun).

The modern concept of United Armenia as used by Woodrow Wilson and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun). Early 1600s spread of Armenians, a few decades after Ottoman conquest, within modern Turkey, per the State Committee of the Real Estate Cadastre of Armenia[22]

Early 1600s spread of Armenians, a few decades after Ottoman conquest, within modern Turkey, per the State Committee of the Real Estate Cadastre of Armenia[22]

See also

Notes

- "The lands of Western Armenia which Mt. Ararat represent..."[9] "mount Ararat is the symbol of banal irredentism for the territories of Western Armenia"[10]"...Ararat, which is in the territory of modern Turkey but symbolizes the dream of all Armenians around the globe about the lands lost to the west of this biblical mountain."[11]

References

- "2011 Census Results" (PDF). armstat.am. National Statistical Service of Republic of Armenia. p. 144.

- Myhill, John (2006). Language, Religion and National Identity in Europe and the Middle East: A historical study. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-272-9351-0.

- "Genocide and the Modern Age: Etiology and Case Studies of Mass Death". Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp 728–729 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- Marie-Aude Baronian; Stephan Besser; Yolande Jansen (2007). Diaspora and Memory: Figures of Displacement in Contemporary Literature, Arts and Politics. Rodopi. p. 174. ISBN 9789042021297.

- Shirinian, Lorne (1992). The Republic of Armenia and the rethinking of the North-American Diaspora in literature. E. Mellen Press. p. ix. ISBN 9780773496132.

This date is important, for it marks the beginning of the Armenian Genocide, which destroyed the over two-thousand-year Armenian presence in historical, Western Armenia.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (2008). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 9781412835923.

- Jones, Adam (2013). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 9781134259816.

- Shirinian, Lorne (1992). The Republic of Armenia and the rethinking of the North-American Diaspora in literature. Edwin Mellen Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0773496132.

- Adriaans, Rik (2011). "Sonorous Borders: National Cosmology & the Mediation of Collective Memory in Armenian Ethnopop Music". University of Amsterdam. p. 48. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Khojoyan, Sara (1 August 2008). "Beyond and Inside: Turk look on Ararat with Armenian perception". ArmeniaNow.

- Hacikyan, Agop Jack (2005). The Heritage of Armenian Literature: From the eighteenth century to modern times. Wayne State University Press.

- "Genocide and the Modern Age: Etiology and Case Studies of Mass Death". Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Dowling, Timothy C. (2014). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. pp. 728–729. ISBN 1598849484.

- Armenia

- Kirakossian, Arman J. (2004). British Diplomacy and the Armenian Question, from the 1830s to 1914. Taderon.

- Armenia at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Spencer Tucker (2005). World War I: Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1142–. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

- The Armenian Review. Hairenik Association. 1956.

The Sazonov-Paleologue agreement of April 26, 1916 between Great Britain and France and the Sykes–Picot agreement of May 16, 1916 between Great Britain and France which together made up the Anglo-Franco-Russian accord of 1916...

- "Western Armenians are preparing". A1+. 16 November 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008.

- Papian 2009, p. 37.

- State Committee of the Real Estate Cadastre of the Republic of Armenia (2007). Հայաստանի Ազգային Ատլաս (National Atlas of Armenia), Yerevan: Center of Geodesy and Cartography SNPO, p. 102 see map

Further reading

- Arman J. Kirakosian, "English Policy towards Western Armenia and Public Opinion in Great Britain (1890–1900)", Yerevan, 1981, 26 p. (in Armenian and Russian).

- Armen Ayvazyan, "Western Armenia vs Eastern Anatolia", Europe & Orient – n°4, 2007