Treaty of Paris (1856)

The Treaty of Paris of 1856 settled the Crimean War between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia.[1]

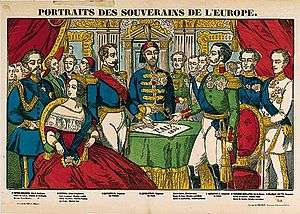

Edouard Louis Dubufe, Congrès de Paris, 1856, Palace of Versailles. | |

| Type | Multilateral Treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | 30 March 1856 |

| Location | Paris, France |

| Original signatories | France, UK, Ottoman Empire, Sardinia, Prussia, Austria, Russia[1] |

| Ratifiers | France, UK, Ottoman Empire, Sardinia, Prussia, Austria, Russian Empire |

| Language | French |

The treaty, signed on 30 March 1856 at the Congress of Paris, made the Black Sea neutral territory, closed it to all warships and prohibited fortifications and the presence of armaments on its shores.

The treaty marked a severe setback to Russian influence in the region. Conditions for the return of Sevastopol and other towns and cities in the south of Crimea to Russia were severe since no naval or military arsenal could be established by Russia on the coast of the Black Sea.

Summary

The Treaty of Paris was signed on 30 March 1856 at the Congress of Paris with Russia on one side of the negotiating table and France, Britain, the Ottoman Empire and Sardinia Piedmont on the other side. The treaty came about to resolve the Crimean War, which had begun on 23 October 1853, when the Porte formally declared war on Russia after it moved troops into the Danubian Principalities.[2]

The Treaty of Paris would have long-lasting implications on the future of the Ottoman Empire although at the time, it was seen as an achievement of the Tanzimat policy of reform. The Western European powers pledged to maintain the integrity of the Ottoman Empire and restored the respective territories of the Russian and the Ottoman Empires to their prewar boundaries. They also neutralized the Black Sea for international trade, which greatly weakened Russia militarily. Moldavia and Walachia (Romania) were recognized as quasi-independent states under Ottoman suzerainty. They gained the left bank of the mouth of the Danube and part of Bessarabia from Russia.[3]

Negotiations

.jpg)

As the first modern war came to a close after eighteen months, all sides of the war wanted to come to a lasting resolution. However, competing goals would spoil the idea of a lasting and definite peace treaty. Even within the allies, conflicting notions of what the peace should entail created a less solid peace deal, leading to further problems for the Ottoman Empire, especially in terms of its relations with the Russian Empire and the Concert of Europe. Also, mistrust between the French and British allies during the war effort compounded problems in hammering out a comprehensive peace plan.[4]

The war might have formally come to a close, but another war became more likely because of the treaty.[5][6]

Russian aims

Despite losing the war, the Russians wanted to ensure that they left the Congress of Paris with some strength left in their empire and with some of their wartime possessions under their rule. When Alexander II took the crown of Russia in 1855, he inherited a potential crisis that threatened to collapse his empire. Problems all throughout the empire, stretching from parts of Finland to Poland and Crimea and many tribal conflicts, stretched the Russian economy to the brink of collapse. Russia knew that within a few months, a total defeat in the war was imminent, which would mean the complete humiliation of Russia on a global scale. Peace talks were pursued by Alexander II with Britain and France in Paris in 1856 as a means of attempting to keep some imperial possession but also of stopping the deaths of thousands of its barely-trained army reserves as well as an economic crisis.[4] One main aim of the Russians was ending war with the appearance of some strength left in the Russian bear, which had once terrified the Western allies. It contrived "to turn defeat into victory... through... peacetime [internal] reforms and diplomatic initiatives."[7] Like the Ottomans, the Russians desired to turn their attention inward to fix many internal problems, such as the economy and growing unrest in the society that Russia had not done enough in the war effort to crush the weak Ottomans.

British and French aims

The most interesting relationship at the Treaty of Paris negotiations was probably between the French and the British. In the middle of the war, they began to pick up their Napoleonic War rivalry once again. The French blamed many of the defeats of the alliance on the fact that Britain had marched into war without a clear plan of action, as was perhaps illustrated by the celebrated and valourous but fruitless Charge of the Light Brigade during the Battle of Balaclava. The British were increasingly wary throughout the war that the French might capitalise on a weakened Russia and focus their attention on seeking revenge for French military defeats at Trafalgar and Waterloo at the hands of the British.[8]

British and French diplomats and politicians welcomed the Russian peace talks because they would end the war before either ally could turn its attention onto betraying the other.

Britain and France also desired to ensure that the Ottoman Empire came out of the Peace of Paris stronger and able to keep the balance of power in Europe stable. Britain and France hoped that peace and restricting Russian access to key areas in the area, such as the Black Sea, would free up the limping Ottoman Empire to focus on internal issues such as rising tides of nationalism in many nations under the empire's authority. Without the Ottomans being in full control of their empire, the great powers feared that there could be a mad grab for its territory and a strengthening of nations that could pose a threat to the French and the British. A strong Russia and German force, bolstered by the acquisition of lands from a decaying Ottoman Empire, scared them into desiring nothing more than protecting the "sick man of Europe" from further external stress.[9]

Thus, the full removal of Russian presence in the Danubian provinces and the Black Sea served both to protect British dominance and to weaken Russia.

Russian losses

The Ottoman, British and French governments would have desired a more crushing defeat for Russia, which was still crippled in many key areas. The Russians had lost over 500,000 troops and knew that pressing further militarily with their untrained army would have cost even more lives.

Russia was forced to withdraw from the Danubian Principalities, where it had started a period of common tutelage for the Ottomans and the Congress of Great Powers.[10]

Russia had to return to Moldavia part of the territory it had annexed in 1812 (to the mouth of the Danube, in southern Bessarabia). Russia thus lost its influence over the Romanian principalities (Moldavia and Wallachia), which, together with the Principality of Serbia, were given greater independence.

Also, Russia was forced to abandon its claim, the pretext for the war, to protect Christians in the Ottoman Empire in favour of France.

Russian battleships were banned from sailing the Black Sea[11], which greatly decreased Russian influence over the essential warm water port.

Another loss that Russia needed to contend with after the war was the stretched economy and a restless people, unhappy with how the war had been executed. The political and social unrest, compounded by economic decay, led its intellectuals to use the defeat to demand fundamental reform of the government and the social system. The emancipation of the serfs and the spread of revolutionary ideas were largely due to the defeat.

Treaty of Paris: debates

Treaty of Paris: debates- A medallion issued to celebrate the end of the Crimean War and the Treaty of Paris, made from a soft, "silver colour" alloy

Short-term consequences

One immediate result of the treaty was the reopening of the Black Sea for safe, open international trade after both the naval war and the presence of Russian warships had made trade difficult. The Russian fleet in the Black Sea was formidable and sank the Turkish fleet.

Now that the Russian fleet was banned from the waterway, peaceful trade could return.[12]

The Peace of Paris also allowed the war to end and for temporary stability to return to Europe. The Ottomans could focus their attention on the crumbling internal infrastructure, and the Russians could look to their faltering economy. Tensions built up by opportunistic fears between Britain and France could temporarily ease.

However, nothing in the Peace of Paris could keep Europe stable for the long run, as much more troubling long-term consequences were caused.

The Peace of Paris was also affected by the general public in places such as France and Britain because the Crimean War, as one of the first modern wars, was also the first in which the general public received timely and accurate media coverage of the carnage. The British prime minister, Lord Aberdeen, who was viewed as being incompetent with the war effort, lost a vote in Parliament and resigned in favour of Lord Palmerston, who was seen as having a clearer plan to victory.[4] Peace was necessary because for the first time, foreign policy was very accessible to the people, who demanded an end to the bloodshed.

Long-term consequences

Nationalism was bolstered in many ways by the Crimean War, and very little could be done at a systemic level to stem the tides of growing nationalist sentiment in many nations. The Ottoman Empire, for the next few decades until World War I, had to face a number of patriotic uprisings in many of its provinces. No longer capable of withstanding the internal forces tearing it apart, the empire was splintering, as many ethnic groups cried out for more rights, most notably self-rule. Britain and France may have allowed the situation in Europe to stabilise briefly, but the Peace of Paris did little to create lasting stability in the Concert of Europe. The Ottomans joined the Concert of Europe after the Peace was signed, but most European nations looked to the crumbling empire with either hungry or terrified eyes.

The war revealed to the world just how important solving the "Eastern Question" was to the stability of Europe; however, the Peace of Paris provided no clear answer or guidance.[6]

The importance of the Ottoman Empire to Britain and France in maintaining the balance of power in the Black and the Mediterranean Seas made many view the signing of the Treaty of Paris to be the entrance of the Ottoman Empire to the European international theatre. Greater penetration of European influence into Ottoman international law and a decline in emphasis of Islamic practices in their legal system illustrate more of an inclusion of the Ottoman Empire into European politics and disputes, leading to its major role in the First World War.[13]

Austria and Germany were affected by nationalism as a result of the signing of the Peace of Paris. Austria was normally an ally of Russia but was neutral during the war, mobilized troops against Russia and sent at least an ultimatum asking the withdrawal of Russian armies from the Balkans.

After the Russian defeat, relations between the two nations, the most conservative in Europe, remained very strained. Russia, the gendarme of conservatism and the saviour of Austria during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, angrily resented the failure of Austria to help or assist its former ally, which contributed to Russia's non-intervention in the 1859 Franco-Austrian War, which meant the end of Austrian influence in Italy; in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, with the loss of its influence in most German-speaking land; and in the Ausgleich (compromise) with Hungary of 1867, which meant the sharing of the power in the Danubian Empire with the Magyars. The status of Austria as a great power, after the unifications of Germany, Italy and, to a lesser extent, of Romania, was now severely diminished. Austria slowly became a little more than a German satellite state.

A unified and strengthened Germany was not a pleasant thought for many in Britain and France[14] since it would pose a threat to both French borders and British political and economic interest in the East.

Essentially, the war that sought to stabilise power relations in Europe brought about by a temporary peace. The great powers only strengthened nationalist aspirations of ethnic groups, under the control of the victorious Ottomans and of the German states. By 1877, the Russians and the Ottomans would once again be at war.[6]

Provisions

The treaty admitted the Ottoman Empire to the European concert, and the Powers promised to respect its independence and territorial integrity. Russia gave up some and relinquished its claim to a protectorate over the Christians in the Ottoman domains. The Black Sea was demilitarised, and an international commission was set up to guarantee freedom of commerce and navigation on the Danube River.

Moldavia and Wallachia would stay under nominal Ottoman rule but be granted independent constitutions and national assemblies, which were to be monitored by the victorious powers. A project of a referendum was to be set in place to monitor the will of the peoples on unification. Moldavia recovered part of Bessarabia (including part of Budjak), which it had held prior to 1812, creating a buffer between the Ottoman Empire and Russia in the west. The United Principalities of Romania, which would later be formed from the two territories, would remain an Ottoman vassal state until 1877.

New rules of wartime commerce were set out in the Declaration of Paris: (1) privateering was illegal; (2) a neutral flag covered enemy goods except contraband; (3) neutral goods, except contraband, were not liable to capture under an enemy flag; (4) a blockade, to be legal, had to be effective.[15]

The treaty also demilitarised the Åland Islands in the Baltic Sea, which belonged to the autonomous Russian Grand Duchy of Finland. The fortress Bomarsund had been destroyed by British and French forces in 1854, and the alliance wanted to prevent its future use as a Russian military base.

Signing parties

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

See also

- In 2006, Finland celebrated the 150th anniversary of the demilitarisation of the Åland Islands by issuing a commemorative coin. Its obverse depicts a pine tree, very typical in the Åland Islands, and the reverse features a boat's stern and rudder, with a dove perched on the tiller, a symbol of 150 years of peace.

- Berwick-upon-Tweed – an apocryphal story concerns Berwick's status with Russia

References

- Hertslet, Edward (1875), "GENERAL TREATY between Great Britain, Austria, France, Prussia, Russia, Sardinia and Turkey, signed at Paris on 30th March 1856 (Translation)" in The Map of Europe by Treaty; which have taken place since the general peace of 1814. With numerous maps and notes, vol. II, London: Butterworth, pages 1250-65; Pierre Albin (1912), "ACTE GENERAL DU CONGRES DE PARIS (30 mars 1856)" ,Les grands traités politiques. Recueil des principaux textes diplomatique depuis 1815 jusqu'à nos jours, Paris: F.Alcan, p. 170-180

- C. D. Hazen et al., Three Peace Congresses of the Nineteenth Century (1917).

- Winfried Baumgart, and Ann Pottinger Saab, Peace of Paris, 1856: Studies in War, Diplomacy & Peacemaking (1981).

- James, Brian. ALLIES IN DISARRAY: The Messy End of the Crimean War. History Today, 58, no. 3, 2008, pp. 24–31.

- Temperley, Harold. The Treaty of Paris of 1856 and Its Execution. The Journal of Modern History, 4, no. 3, 1932, pp. 387–414.

- Pearce, Robert. The Results of the Crimean War. History Review, 70, 2011, pp. 27–33

- Gorizontoy, Leonid. The Crimean War as a Test of Russia's Imperial Durability.Russian Studies in History, 51, no.1, 2012, pp. 65–94

- James, Brian. ALLIES IN DISARRAY: The Messy End of the Crimean War, History Today, 58, no. 3, 2008, pp. 24–31.

- Pearce, Robert. The Results of the Crimean War. History Review 70, 2011, pp. 27–33

- Wedgewood Benn, David.The Crimean War and its lessons for today. International Affairs, 88, no. 2, 2012, pp. 387–391

- Replaced by Treaty of London (1871).

- Wedgewood Benn, David. The Crimean War:and its lessons for today. International Affairs, 88, no. 2, 2012, pp. 387–391

- Palabiyik, Mustafa Serdar, The Emergence of the Idea of ‘InternationalLaw’ in the Ottoman Empire before the Treaty of Paris (1856), Middle Eastern Studies, 50:2, 2014, 233-251.

- Trager, Robert. Long-Term Consequences of Aggressive Diplomacy: European Relations after Austrian Crimean War Threats. Security Studies, 21, no. 2, 2012, pp. 232–265.

- A.W. Ward; G. P. Gooch (1970). The Cambridge History of British Foreign Policy 1783–1919. Cambridge U.P,. pp. 390–91.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treaty of Paris, 1856. |

Sources and further reading

- Adanir, Fikret. "Turkey's entry into the Concert of Europe." European Review 13#3 (2005): pp 395-417.

- Baumgart, Winfried, and Ann Pottinger Saab. Peace of Paris, 1856: Studies in War, Diplomacy & Peacemaking (1981), 230 pp

- Figes, Orlando. The Crimean War: A History (2010) pp 411–65.

- Hazen, C. D. et al. Three Peace Congresses of the Nineteenth Century (1917) pp 23-44. online

- Jelavich, Barbara. St. Petersburg and Moscow: tsarist and Soviet foreign policy, 1814-1974 (Indiana University Press, 1974) pp 128–33.

- Mosse, W. E. "The Triple Treaty of 15 April 1856." English Historical Review 67.263 (1952): pp 203-229. in JSTOR

- Taylor, A.J.P. The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848–1918 (1954) pp 83–97

- Temperley, Harold. "The Treaty of Paris of 1856 and Its Execution," Journal of Modern History (1932) 4#3 pp 387–414 in JSTOR