Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was the period in American history that lasted from 1863 to 1877 following the American Civil War (1861–65) and is a significant chapter in the history of American civil rights. Reconstruction ended the remnants of Confederate secession and abolished slavery, making the newly freed slaves citizens with civil rights ostensibly guaranteed by three new constitutional amendments. Reconstruction also refers to the attempt to transform the 11 Southern former Confederate states, as directed by Congress, and the role of the Union states in that transformation.

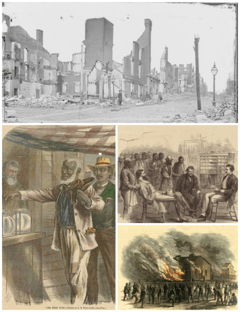

The ruins of Richmond, Virginia, the former Confederate capital, after the American Civil War; newly freed African Americans voting for the first time in 1867;[1] Office of the Freedmen's Bureau in Memphis, Tennessee; Memphis Riots of 1866 | |

| Date | December 8, 1863 – March 31, 1877 |

|---|---|

| Duration | 13 years, 3 months, 3 weeks and 2 days |

| Location | Southern United States |

| Also known as | Reconstruction, Reconstruction era of the United States, Reconstruction of the Rebel States, Reconstruction of the South, Reconstruction of the Southern States |

| Cause | American Civil War |

| Organized by | United States Government |

| Participants |

|

| Periods in United States history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Three visions of Civil War memory appeared during Reconstruction: the reconciliationist vision, which was rooted in coping with the death and devastation the war had brought; the white supremacist vision, which included racial segregation and the preservation of white political and cultural domination in the South; and the emancipationist vision, which sought full freedom, citizenship, male suffrage, and constitutional equality for African Americans.[2]

When Republican President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at the end of the Civil War, Vice President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee and former slave holder, became president. Johnson favored rapid measures to bring the South back into the Union, allowing the Southern states to determine the rights of former slaves. Lincoln's last speeches show that he leaned toward supporting the suffrage of all freedmen, whereas Johnson and the Democratic Party were strongly opposed to this.[3] Radical Republicans in Congress sought stronger, federal measures to upgrade the rights of African Americans, including the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, while curtailing the rights of former Confederates, such as through the provisions of the Wade–Davis Bill. Johnson, the most prominent Southerner to oppose the Confederacy, followed a lenient policy toward ex-Confederates.

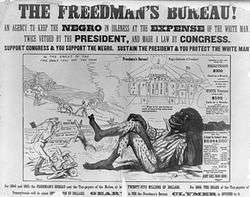

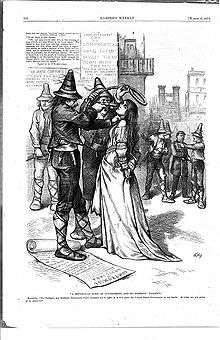

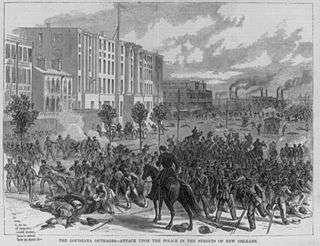

Johnson's weak Reconstruction policies prevailed until the congressional elections of 1866, which followed outbreaks of violence against blacks in the former rebel states, including the Memphis riots of 1866 and the New Orleans massacre of 1866. The subsequent 1866 election gave Republicans a majority in Congress, enabling them to pass the 14th Amendment, federalizing equal rights for freedmen, and dissolving rebel state legislatures until new state constitutions were passed in the South. A Republican coalition came to power in nearly all of the Southern states and set out to transform the society by setting up a free labor economy, using the U.S. Army and the Freedmen's Bureau. The bureau protected the legal rights of freedmen, negotiated labor contracts, and set up schools and churches for them. Thousands of Northerners came to the South as missionaries, teachers, businessmen, and politicians. Hostile whites began referring to these politicians as "carpetbaggers."

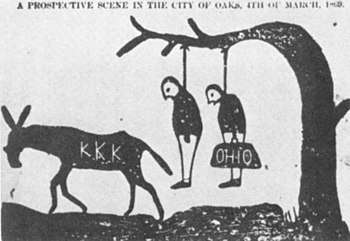

In early 1866, Congress passed the Freedmen's Bureau and Civil Rights Bills and sent them to Johnson for his signature. The first bill extended the life of the bureau, originally established as a temporary organization charged with assisting refugees and freed slaves, while the second defined all persons born in the United States as national citizens with equality before the law. After Johnson vetoed the bills, Congress overrode his vetoes, making the Civil Rights Act the first major bill in the history of the United States to become law through an override of a presidential veto. The Radicals in the House of Representatives, frustrated by Johnson's opposition to congressional Reconstruction, filed impeachment charges. The action failed by one vote in the Senate. The new national Reconstruction laws, in particular laws requiring suffrage (the right to vote) for freedmen, incensed white supremacists in the South, giving rise to the Ku Klux Klan. During 1867–69, the Klan murdered Republicans and outspoken freedmen in the South, including Arkansas Congressman James M. Hinds.

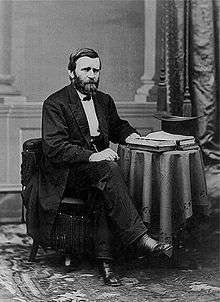

Elected in 1868, Republican President Ulysses S. Grant supported congressional Reconstruction and enforced the protection of African Americans in the South through the use of the Enforcement Acts passed by Congress. Grant used the Enforcement Acts to combat the Ku Klux Klan, which was essentially wiped out, although a new incarnation of the Klan eventually would again come to national prominence in the 1920s. Nevertheless, Grant was unable to resolve the escalating tensions inside the Republican Party between Northern Republicans and Southern Republicans (this latter group would be labelled "scalawags" by those opposing Reconstruction). Meanwhile, "Redeemers," self-styled conservatives in close cooperation with a faction of the Democratic Party, strongly opposed Reconstruction.[4] They alleged widespread corruption by the "carpetbaggers," excessive state spending, and ruinous taxes.

Public support for Reconstruction policies, requiring continued supervision of the South, faded in the North with the rise of the Liberal Republicans in 1872 and after the Democrats, who also strongly opposed Reconstruction, regained control of the House of Representatives in 1874. In 1877, as part of a congressional bargain to elect Republican Rutherford B. Hayes as president following the disputed 1876 presidential election, U.S. Army troops were withdrawn from the three states (South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida) where they still remained. This marked the end of Reconstruction.

Historian Eric Foner argues:

What remains certain is that Reconstruction failed, and that for Blacks its failure was a disaster whose magnitude cannot be obscured by the genuine accomplishments that did endure.[5]

Dating the Reconstruction era

In different states, Reconstruction began and ended at different times; though federal Reconstruction ended with the Compromise of 1877. In recent decades most historians follow Eric Foner in dating the Reconstruction of the South as starting in 1863, with the Emancipation Proclamation and the Port Royal Experiment, rather than 1865.[6] The usual ending for Reconstruction has always been 1877.

Reconstruction policies were debated in the North when the war began, and commenced in earnest after Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863.[7] Textbooks covering the entire range of American history North, South and West typically use 1865–1877 for their chapter on the Reconstruction era. Foner, for example, does this in his general history of the United States, Give Me Liberty! (2005).[8] However, in his 1988 monograph specializing on the situation in the South, titled Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, he begins in 1863.

Overview

As Confederate states came back under control of the U.S. Army, President Abraham Lincoln set up reconstructed governments in Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana during the war. He experimented by giving land to Blacks in South Carolina. By fall 1865, the new President Andrew Johnson declared the war goals of national unity and the ending of slavery achieved and Reconstruction completed. Republicans in Congress, refusing to accept Johnson's lenient terms, rejected and refused to seat new members of Congress, some of whom had been high-ranking Confederate officials a few months before. Johnson broke with the Republicans after vetoing two key bills that supported the Freedmen's Bureau and provided federal civil rights to the freedmen. The 1866 Congressional elections turned on the issue of Reconstruction, producing a sweeping Republican victory in the North, and providing the Radical Republicans with sufficient control of Congress to override Johnson's vetoes and commence their own "Radical Reconstruction" in 1867.[9] That same year, Congress removed civilian governments in the South, and placed the former Confederacy under the rule of the U.S. Army (except in Tennessee, where anti-Johnson Republicans were already in control). The Army conducted new elections in which the freed slaves could vote, while whites who had held leading positions under the Confederacy were temporarily denied the vote and were not permitted to run for office.

In 10 states, excluding Virginia, coalitions of freedmen, recent Black and white arrivals from the North ("carpetbaggers"), and white Southerners who supported Reconstruction ("scalawags") cooperated to form Republican biracial state governments. They introduced various Reconstruction programs including: funding public schools, establishing charitable institutions, raising taxes, and funding public improvements such as improved railroad transportation and shipping.

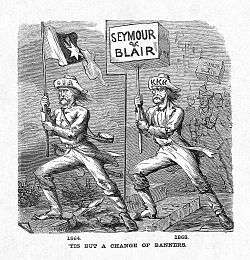

In the 1860s and 1870s, the terms "Radical" and "conservative" had distinct meanings. "Conservative" was the name of a faction, often led by the planter class. Conservative opponents called the Republican regimes corrupt and instigated violence toward freedmen and whites who supported Reconstruction. Most of the violence was carried out by members of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a secretive terrorist organization closely allied with the Southern Democratic Party. Klan members attacked and intimidated Blacks seeking to exercise their new civil rights, as well as Republican politicians in the South favoring those civil rights. One such politician murdered by the Klan on the eve of the 1868 presidential election was Republican Congressman James M. Hinds of Arkansas. Widespread violence in the South led to federal intervention by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1871, which suppressed the Klan. Nevertheless, white Democrats, calling themselves "Redeemers", regained control of the South state by state, sometimes using fraud and violence to control state elections. A deep national economic depression following the Panic of 1873 led to major Democratic gains in the North, the collapse of many railroad schemes in the South, and a growing sense of frustration in the North.

The end of Reconstruction was a staggered process, and the period of Republican control ended at different times in different states. With the Compromise of 1877, military intervention in Southern politics ceased and Republican control collapsed in the last three state governments in the South. This was followed by a period which white Southerners labeled "Redemption," during which white-dominated state legislatures enacted Jim Crow laws, disenfranchising most Blacks and many poor whites through a combination of constitutional amendments and election laws beginning in 1890. The white Southern Democrats' memory of Reconstruction played a major role in imposing the system of white supremacy and second-class citizenship for blacks using laws known as Jim Crow laws.[10]

Purpose

Reconstruction addressed how the 11 seceding rebel states in the South would regain what the Constitution calls a "republican form of government" and be re-seated in Congress, the civil status of the former leaders of the Confederacy, and the constitutional and legal status of freedmen, especially their civil rights and whether they should be given the right to vote. Intense controversy erupted throughout the South over these issues.[lower-roman 1]

Passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments is the constitutional legacy of Reconstruction. These Reconstruction Amendments established the rights that led to Supreme Court rulings in the mid-20th century that struck down school segregation. A "Second Reconstruction," sparked by the Civil Rights Movement, led to civil-rights laws in 1964 and 1965 that ended legal segregation and re-opened the polls to blacks.

The laws and constitutional amendments that laid the foundation for the most radical phase of Reconstruction were adopted from 1866 to 1871. By the 1870s, Reconstruction had officially provided freedmen with equal rights under the Constitution, and blacks were voting and taking political office. Republican legislatures, coalitions of whites and blacks, established the first public school systems and numerous charitable institutions in the South. White paramilitary organizations, especially the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) as well as the White League and Red Shirts, formed with the political aim of driving out the Republicans. They also disrupted political organizing and terrorized blacks to bar them from the polls.[11] President Grant used federal power to effectively shut down the KKK in the early 1870s, though the other, smaller groups continued to operate. From 1873 to 1877, conservative whites (calling themselves "Redeemers") regained power in the Southern states. They constituted the Bourbon wing of the national Democratic Party.

In the 1860s and 1870s, leaders who had been Whigs were committed to economic modernization, built around railroads, factories, banks, and cities.[12] Most of the "Radical" Republicans in the North were men who believed in integrating African Americans by providing them civil rights as citizens, along with free enterprise; most were also modernizers and former Whigs.[13] The "Liberal Republicans" of 1872 shared the same outlook except that they were especially opposed to the corruption they saw around President Grant, and believed that the goals of the Civil War had been achieved, and that the federal military intervention could now end.

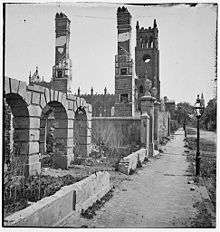

Material devastation of the South in 1865

Reconstruction played out against an economy in ruins. The Confederacy in 1861 had 297 towns and cities, with a total population of 835,000 people; of these, 162, with 681,000 people, were at some point occupied by Union forces. 11 were destroyed or severely damaged by war action, including Atlanta (with an 1860 population of 9,600), Charleston, Columbia, and Richmond (with prewar populations of 40,500, 8,100, and 37,900, respectively); the 11 contained 115,900 people according to the 1860 Census, or 14% of the urban South. The number of people who lived in the destroyed towns represented just over 1% of the Confederacy's combined urban and rural populations. The rate of damage in smaller towns was much lower—only 45 courthouses were burned out of a total of 830.[14]

Farms were in disrepair, and the prewar stock of horses, mules, and cattle was much depleted; 40% of the South's livestock had been killed.[15] The South's farms were not highly mechanized, but the value of farm implements and machinery according to the 1860 Census was $81 million and was reduced by 40% by 1870.[16] The transportation infrastructure lay in ruins, with little railroad or riverboat service available to move crops and animals to market.[17] Railroad mileage was located mostly in rural areas; over two-thirds of the South's rails, bridges, rail yards, repair shops, and rolling stock were in areas reached by Union armies, which systematically destroyed what they could. Even in untouched areas, the lack of maintenance and repair, the absence of new equipment, the heavy over-use, and the deliberate relocation of equipment by the Confederates from remote areas to the war zone ensured the system would be ruined at war's end.[14] Restoring the infrastructure—especially the railroad system—became a high priority for Reconstruction state governments.[18]

.jpg)

The enormous cost of the Confederate war effort took a high toll on the South's economic infrastructure. The direct costs to the Confederacy in human capital, government expenditures, and physical destruction from the war totaled $3.3 billion. By early 1865, the Confederate dollar was worth little due to high inflation. When the war ended, Confederate currency and bank deposits were worth zero, making the banking system a near-total loss. People had to resort to bartering services for goods, or else try to obtain scarce Union dollars. With the emancipation of the Southern slaves, the entire economy of the South had to be rebuilt. Having lost their enormous investment in slaves, white plantation owners had minimal capital to pay freedmen workers to bring in crops. As a result, a system of sharecropping was developed, in which landowners broke up large plantations and rented small lots to the freedmen and their families. The main feature of the Southern economy changed from an elite minority of landed gentry slaveholders into a tenant farming agriculture system.[19]

The end of the Civil War was accompanied by a large migration of new freed people to the cities.[20] In the cities, Black people were relegated to the lowest paying jobs such as unskilled and service labor. Men worked as rail workers, rolling and lumber mills workers, and hotel workers. The large population of slave artisans during the antebellum period had not been translated into a large number of freedmen artisans during Reconstruction.[21] Black women were largely confined to domestic work employed as cooks, maids, and child nurses. Others worked in hotels. A large number became laundresses. The dislocations had a severe negative impact on the black population, with a large amount of sickness and death.[22]

Over a quarter of Southern white men of military age—the backbone of the South's white workforce—died during the war, leaving countless families destitute.[15] Per capita income for white Southerners declined from $125 in 1857 to a low of $80 in 1879. By the end of the 19th century and well into the 20th century, the South was locked into a system of poverty. How much of this failure was caused by the war and by previous reliance on agriculture remains the subject of debate among economists and historians.[23]

Restoring the South to the Union

During the Civil War, the Radical Republican leaders argued that slavery and the Slave Power had to be permanently destroyed. Moderates said this could be easily accomplished as soon as the Confederate States Army surrendered and the Southern states repealed secession and accepted the Thirteenth Amendment–most of which happened by December 1865.[24]

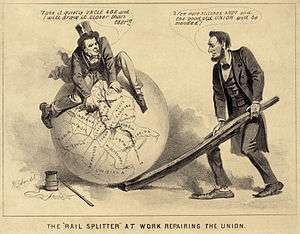

President Lincoln was the leader of the moderate Republicans and wanted to speed up Reconstruction and reunite the nation painlessly and quickly. Lincoln formally began Reconstruction in late 1863 with his ten percent plan, which went into operation in several states but which Radical Republicans opposed.

1864: Wade–Davis Bill

The issue of loyalty emerged in the debates over the Wade–Davis Bill of 1864. The bill required voters to take the "ironclad oath," swearing that they had never supported the Confederacy or been one of its soldiers. Pursuing a policy of "malice toward none" announced in his second inaugural address,[25] Lincoln asked voters only to support the Union.[26] Lincoln pocket vetoed the Wade–Davis Bill, which was much more strict than the ten percent plan.[9][27]

Following Lincoln's veto, the Radicals lost support but regained strength after Lincoln's assassination in April 1865.

1865

Upon Lincoln's assassination in April 1865, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, who had been elected with Lincoln in 1864 as vice president, became president. Johnson rejected the Radical program of Reconstruction and instead appointed his own governors and tried to finish Reconstruction by the end of 1865. Thaddeus Stevens vehemently opposed President Johnson's plans for an abrupt end to Reconstruction, insisting that Reconstruction must "revolutionize Southern institutions, habits, and manners... The foundations of their institutions...must be broken up and relaid, or all our blood and treasure have been spent in vain."[28] Johnson broke decisively with the Republicans in Congress when he vetoed the Civil Rights Act in early 1865. While Democrats celebrated, the Republicans rallied, passed the bill again, and overrode Johnson's repeat veto.[29] Full-scale political warfare now existed between Johnson (now allied with the Democrats) and the Radical Republicans.[30]

Since the war had ended, Congress rejected Johnson's argument that he had the war power to decide what to do. Congress decided it had the primary authority to decide how Reconstruction should proceed, because the Constitution stated the United States had to guarantee each state a republican form of government. The Radicals insisted that meant Congress decided how Reconstruction should be achieved. The issues were multiple: Who should decide, Congress or the president? How should republicanism operate in the South? What was the status of the former Confederate states? What was the citizenship status of the leaders of the Confederacy? What was the citizenship and suffrage status of freedmen?[31]

1866

By late 1866, the opposing faction of Radical Republicans was skeptical of Southern intentions. White reactions included outbreaks of mob violence against Black people, such as the Memphis riots of 1866 and the New Orleans massacre of 1866. Radical Republicans demanded a prompt and strong federal response to protect freedmen and curb Southern racism. Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts led the Radicals. Sumner argued that secession had destroyed statehood but the Constitution still extended its authority and its protection over individuals, as in existing U.S. territories.

Stevens and his followers viewed secession as having left the states in a status like new territories. The Republicans sought to prevent Southern politicians from "restoring the historical subordination of Negroes." Since slavery was abolished, the Three-Fifths Compromise no longer applied to counting the population of blacks. After the 1870 Census, the South would gain numerous additional representatives in Congress, based on the population of freedmen.[32] One Illinois Republican expressed a common fear that if the South were allowed to simply restore its previous established powers, that the "reward of treason will be an increased representation."[33]

The election of 1866 decisively changed the balance of power, giving the Republicans two-thirds majorities in both houses of Congress, and enough votes to overcome Johnson's vetoes. They moved to impeach Johnson because of his constant attempts to thwart Radical Reconstruction measures, by using the Tenure of Office Act. Johnson was acquitted by one vote, but he lost the influence to shape Reconstruction policy.[34] The Republican Congress established military districts in the South and used Army personnel to administer the region until new governments loyal to the Union—that accepted the Fourteenth Amendment and the right of freedmen to vote—could be established. Congress temporarily suspended the ability to vote of approximately 10,000 to 15,000 former Confederate officials and senior officers, while constitutional amendments gave full citizenship to all African Americans, and suffrage to the adult men.[35]

With the power to vote, freedmen began participating in politics. While many enslaved people were illiterate, educated Blacks (including fugitive slaves) moved down from the North to aid them, and natural leaders also stepped forward. They elected white and black men to represent them in constitutional conventions. A Republican coalition of freedmen, Southerners supportive of the Union (derisively called "scalawags" by white Democrats), and Northerners who had migrated to the South (derisively called "carpetbaggers")—some of whom were returning natives, but were mostly Union veterans—organized to create constitutional conventions. They created new state constitutions to set new directions for Southern states.[36]

Suffrage

Congress had to consider how to restore to full status and representation within the Union those Southern states that had declared their independence from the United States and had withdrawn their representation. Suffrage for former Confederates was one of two main concerns. A decision needed to be made whether to allow just some or all former Confederates to vote (and to hold office). The moderates in Congress wanted virtually all of them to vote, but the Radicals resisted. They repeatedly imposed the ironclad oath, which would effectively have allowed no former Confederates to vote. Historian Harold Hyman says that in 1866 congressmen "described the oath as the last bulwark against the return of ex-rebels to power, the barrier behind which Southern Unionists and Negroes protected themselves."[37]

Radical Republican leader Thaddeus Stevens proposed, unsuccessfully, that all former Confederates lose the right to vote for five years. The compromise that was reached disenfranchised many Confederate civil and military leaders. No one knows how many temporarily lost the vote, but one estimate placed the number as high as 10,000 to 15,000.[38] However, Radical politicians took up the task at the state level. In Tennessee alone, over 80,000 former Confederates were disenfranchised.[39]

Second, and closely related, was the issue of whether the 4 million freedmen were to be received as citizens: Would they be able to vote? If they were to be fully counted as citizens, some sort of representation for apportionment of seats in Congress had to be determined. Before the war, the population of slaves had been counted as three-fifths of a corresponding number of free whites. By having 4 million freedmen counted as full citizens, the South would gain additional seats in Congress. If Blacks were denied the vote and the right to hold office, then only whites would represent them. Many conservatives, including most white Southerners, Northern Democrats, and some Northern Republicans, opposed black voting. Some Northern states that had referendums on the subject limited the ability of their own small populations of blacks to vote.

Lincoln had supported a middle position: to allow some black men to vote, especially U.S. Army veterans. Johnson also believed that such service should be rewarded with citizenship. Lincoln proposed giving the vote to "the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks."[40] In 1864, Governor Johnson said: "The better class of them will go to work and sustain themselves, and that class ought to be allowed to vote, on the ground that a loyal Negro is more worthy than a disloyal white man."[41]

As president in 1865, Johnson wrote to the man he appointed as governor of Mississippi, recommending: "If you could extend the elective franchise to all persons of color who can read the Constitution in English and write their names, and to all persons of color who own real estate valued at least two hundred and fifty dollars, and pay taxes thereon, you would completely disarm the adversary [Radicals in Congress], and set an example the other states will follow."[42]

Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens, leaders of the Radical Republicans, were initially hesitant to enfranchise the largely illiterate freedmen. Sumner preferred at first impartial requirements that would have imposed literacy restrictions on blacks and whites. He believed that he would not succeed in passing legislation to disenfranchise illiterate whites who already had the vote.[43]

In the South, many poor whites were illiterate as there was almost no public education before the war. In 1880, for example, the white illiteracy rate was about 25% in Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, South Carolina, and Georgia, and as high as 33% in North Carolina. This compares with the 9% national rate, and a black rate of illiteracy that was over 70% in the South.[44] By 1900, however, with emphasis within the black community on education, the majority of blacks had achieved literacy.[45]

Sumner soon concluded that "there was no substantial protection for the freedman except in the franchise." This was necessary, he stated, "(1) For his own protection; (2) For the protection of the white Unionist; and (3) For the peace of the country. We put the musket in his hands because it was necessary; for the same reason we must give him the franchise." The support for voting rights was a compromise between moderate and Radical Republicans.[46]

The Republicans believed that the best way for men to get political experience was to be able to vote and to participate in the political system. They passed laws allowing all male freedmen to vote. In 1867, black men voted for the first time. Over the course of Reconstruction, more than 1,500 African Americans held public office in the South; some of them were men who had escaped to the North and gained educations, and returned to the South. They did not hold office in numbers representative of their proportion in the population, but often elected whites to represent them.[47] The question of women's suffrage was also debated but was rejected.[48] Women eventually gained the right to vote with the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920.

From 1890 to 1908, Southern states passed new state constitutions and laws that disenfranchised most blacks and tens of thousands of poor whites with new voter registration and electoral rules. When establishing new requirements such as subjectively administered literacy tests, in some states, they used "grandfather clauses" to enable illiterate whites to vote.[49]

Southern Treaty Commission

The Five Civilized Tribes that had been relocated to Indian Territory (now part of Oklahoma) held black slaves and signed treaties supporting the Confederacy. During the war, a war among pro-Union and anti-Union Indians had raged. Congress passed a statute that gave the president the authority to suspend the appropriations of any tribe if the tribe is "in a state of actual hostility to the government of the United States...and, by proclamation, to declare all treaties with such tribe to be abrogated by such tribe."[50][51]

As a component of Reconstruction, the Interior Department ordered a meeting of representatives from all Indian tribes who had affiliated with the Confederacy.[52] The council, the Southern Treaty Commission, was first held in Fort Smith, Arkansas in September 1865, and was attended by hundreds of Indians representing dozens of tribes. Over the next several years the commission negotiated treaties with tribes that resulted in additional re-locations to Indian Territory and the de facto creation (initially by treaty) of an unorganized Oklahoma Territory.

Lincoln's presidential Reconstruction

Preliminary events

President Lincoln signed two Confiscation Acts into law, the first on August 6, 1861, and the second on July 17, 1862, safeguarding fugitive slaves from the Confederacy that came over across Union lines and giving them indirect emancipation if their masters continued insurrection against the United States. The laws allowed the confiscation of lands for colonization from those who aided and supported the rebellion. However, these laws had limited effect as they were poorly funded by Congress and poorly enforced by Attorney General Edward Bates.[53][54][55]

In August 1861, Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont, Union commander of the Western Department, declared martial law in Missouri, confiscated Confederate property, and emancipated their slaves. President Lincoln immediately ordered Frémont to rescind his emancipation declaration, stating: "I think there is great danger that...the liberating slaves of traitorous owners, will alarm our Southern Union friends, and turn them against us–perhaps ruin our fair prospect for Kentucky." After Frémont refused to rescind the emancipation order, President Lincoln terminated him from active duty on November 2, 1861. Lincoln was concerned that the border states would secede from the Union if slaves were given their freedom. On May 26, 1862, Union Maj. Gen. David Hunter emancipated slaves in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, declaring all "persons...heretofore held as slaves...forever free." Lincoln, embarrassed by the order, rescinded Hunter's declaration and canceled the emancipation.[56]

On April 16, 1862, Lincoln signed a bill into law outlawing slavery in Washington, D.C., and freeing the estimated 3,500 slaves in the city, and on June 19, 1862, he signed legislation outlawing slavery in all U.S. territories. On July 17, 1862, under the authority of the Confiscation Acts and an amended Force Bill of 1795, he authorized the recruitment of freed slaves into the U.S. Army and seizure of any Confederate property for military purposes.[55][57][58]

Gradual emancipation and compensation

In an effort to keep border states in the Union, President Lincoln, as early as 1861, designed gradual compensated emancipation programs paid for by government bonds. Lincoln desired Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri to "adopt a system of gradual emancipation which should work the extinction of slavery in twenty years." On March 26, 1862, Lincoln met with Senator Charles Sumner and recommended that a special joint session of Congress be convened to discuss giving financial aid to any border states who initiated a gradual emancipation plan. In April 1862, the joint session of Congress met; however, the border states were not interested and did not make any response to Lincoln or any congressional emancipation proposal.[59] Lincoln advocated compensated emancipation during the 1865 River Queen steamer conference.

Colonization

In August 1862, President Lincoln met with African-American leaders and urged them to colonize some place in Central America. Lincoln planned to free the Southern slaves in the Emancipation Proclamation and he was concerned that freedmen would not be well treated in the United States by whites in both the North and South. Although Lincoln gave assurances that the United States government would support and protect any colonies that were established for former slaves, the leaders declined the offer of colonization. Many free blacks had been opposed to colonization plans in the past because they wanted to remain in the United States. President Lincoln persisted in his colonization plan in the belief that emancipation and colonization were both part of the same program. By April 1863, Lincoln was successful in sending black colonists to Haiti as well as 453 to Chiriqui in Central America; however, none of the colonies were able to remain self-sufficient. Frederick Douglass, a prominent 19th-century American civil rights activist, criticized Lincoln by stating that he was "showing all his inconsistencies, his pride of race and blood, his contempt for Negroes and his canting hypocrisy." African Americans, according to Douglass, wanted citizenship and civil rights rather than colonies. Historians are unsure if Lincoln gave up on the idea of African American colonization at the end of 1863 or if he actually planned to continue this policy up until 1865.[55][59][60]

Installation of military governors

Starting in March 1862, in an effort to forestall Reconstruction by the Radicals in Congress, President Lincoln installed military governors in certain rebellious states under Union military control.[61] Although the states would not be recognized by the Radicals until an undetermined time, installation of military governors kept the administration of Reconstruction under presidential control, rather than that of the increasingly unsympathetic Radical Congress. On March 3, 1862, Lincoln installed a loyalist Democrat, Senator Andrew Johnson, as military governor with the rank of brigadier general in his home state of Tennessee.[62] In May 1862, Lincoln appointed Edward Stanly military governor of the coastal region of North Carolina with the rank of brigadier general. Stanly resigned almost a year later when he angered Lincoln by closing two schools for black children in New Bern. After Lincoln installed Brigadier General George Foster Shepley as military governor of Louisiana in May 1862, Shepley sent two anti-slavery representatives, Benjamin Flanders and Michael Hahn, elected in December 1862, to the House, which capitulated and voted to seat them. In July 1862, Lincoln installed Colonel John S. Phelps as military governor of Arkansas, though he resigned soon after due to poor health.

Emancipation Proclamation

In July 1862, President Lincoln became convinced that "a military necessity" was needed to strike at slavery in order to win the Civil War for the Union. The Confiscation Acts were only having a minimal effect to end slavery. On July 22, he wrote a first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation that freed the slaves in states in rebellion. After he showed his Cabinet the document, slight alterations were made in the wording. Lincoln decided that the defeat of the Confederate invasion of the North at Sharpsburg was enough of a battlefield victory to enable him to release the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation that gave the rebels 100 days to return to the Union or the actual proclamation would be issued.

On January 1, 1863, the actual Emancipation Proclamation was issued, specifically naming 10 states in which slaves would be "forever free." The proclamation did not name the states of Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, and Delaware, and specifically excluded numerous counties in some other states. Eventually, as the U.S. Army advanced into the Confederacy millions of slaves were set free. Many of these freedmen joined the U.S. Army and fought in battles against the Confederate forces.[55][60][63] Yet hundreds of thousands of freed slaves died during emancipation from illness that devastated Army regiments. Freed slaves suffered from smallpox, yellow fever, and malnutrition.[64]

Louisiana 10% electorate plan

President Abraham Lincoln was concerned to effect a speedy restoration of the Confederate states to the Union after the Civil War. In 1863, President Lincoln proposed a moderate plan for the Reconstruction of the captured Confederate state of Louisiana. The plan granted amnesty to rebels who took an oath of loyalty to the Union. Black freedmen workers were tied to labor on plantations for one year at a pay rate of $10 a month.[65] Only 10% of the state's electorate had to take the loyalty oath in order for the state to be readmitted into the U.S. Congress. The state was required to abolish slavery in its new state constitution. Identical Reconstruction plans would be adopted in Arkansas and Tennessee. By December 1864, the Lincoln plan of Reconstruction had been enacted in Louisiana and the legislature sent two senators and five representatives to take their seats in Washington. However, Congress refused to count any of the votes from Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee, in essence rejecting Lincoln's moderate Reconstruction plan. Congress, at this time controlled by the Radicals, proposed the Wade–Davis Bill that required a majority of the state electorates to take the oath of loyalty to be admitted to Congress. Lincoln pocket-vetoed the bill and the rift widened between the moderates, who wanted to save the Union and win the war, and the Radicals, who wanted to effect a more complete change within Southern society.[66][67] Frederick Douglass denounced Lincoln's 10% electorate plan as undemocratic since state admission and loyalty only depended on a minority vote.[68]

Legalization of slave marriages

Before 1864, slave marriages had not been recognized legally; emancipation did not affect them.[20] When freed, many made official marriages. Before emancipation, slaves could not enter into contracts, including the marriage contract. Not all free people formalized their unions. Some continued to have common-law marriages or community-recognized relationships.[69] The acknowledgement of marriage by the state increased the state's recognition of freed people as legal actors and eventually helped make the case for parental rights for freed people against the practice of apprenticeship of black children.[70] These children were legally taken away from their families under the guise of "providing them with guardianship and 'good' homes until they reached the age of consent at twenty-one" under acts such as the Georgia 1866 Apprentice Act.[71] Such children were generally used as sources of unpaid labor.

Freedmen's Bureau

On March 3, 1865, the Freedmen's Bureau Bill became law, sponsored by the Republicans to aid freedmen and white refugees. A federal bureau was created to provide food, clothing, fuel, and advice on negotiating labor contracts. It attempted to oversee new relations between freedmen and their former masters in a free labor market. The act, without deference to a person's color, authorized the bureau to lease confiscated land for a period of three years and to sell it in portions of up to 40 acres (16 ha) per buyer. The bureau was to expire one year after the termination of the war. Lincoln was assassinated before he could appoint a commissioner of the bureau. A popular myth was that the act offered 40 acres and a mule, or that slaves had been promised this.

With the help of the bureau, the recently freed slaves began voting, forming political parties, and assuming the control of labor in many areas. The bureau helped to start a change of power in the South that drew national attention from the Republicans in the North to the conservative Democrats in the South. This is especially evident in the election between Grant and Seymour (Johnson did not get the Democratic nomination), where almost 700,000 black voters voted and swayed the election 300,000 votes in Grant's favor.

Even with the benefits that it gave to the freedmen, the Freedmen's Bureau was unable to operate effectively in certain areas. Terrorizing freedmen for trying to vote, hold a political office, or own land, the Ku Klux Klan was the nemesis of the Freedmen's Bureau.[72][73][74]

Bans color discrimination

Other legislation was signed that broadened equality and rights for African Americans. Lincoln outlawed discrimination on account of color, in carrying U.S. mail, in riding on public street cars in Washington, D.C., and in pay for soldiers.[75]

February 1865 peace conference

Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward met with three Southern representatives to discuss the peaceful Reconstruction of the Union and the Confederacy on February 3, 1865, in Hampton Roads, Virginia. The Southern delegation included Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens, John Archibald Campbell, and Robert M. T. Hunter. The Southerners proposed the Union recognition of the Confederacy, a joint Union-Confederate attack on Mexico to oust dictator Maximilian I, and an alternative subordinate status of servitude for blacks rather than slavery. Lincoln flatly rejected recognition of the Confederacy, and said that the slaves covered by his Emancipation Proclamation would not be re-enslaved. He said that the Union states were about to pass the Thirteenth Amendment outlawing slavery. Lincoln urged the governor of Georgia to remove Confederate troops and "ratify this constitutional amendment prospectively, so as to take effect—say in five years... Slavery is doomed." Lincoln also urged compensated emancipation for the slaves as he thought the North should be willing to share the costs of freedom. Although the meeting was cordial, the parties did not settle on agreements.[76]

Historical legacy debated

Lincoln continued to advocate his Louisiana Plan as a model for all states up until his assassination on April 15, 1865. The plan successfully started the Reconstruction process of ratifying the Thirteenth Amendment in all states. Lincoln is typically portrayed as taking the moderate position and fighting the Radical positions. There is considerable debate on how well Lincoln, had he lived, would have handled Congress during the Reconstruction process that took place after the Civil War ended. One historical camp argues that Lincoln's flexibility, pragmatism, and superior political skills with Congress would have solved Reconstruction with far less difficulty. The other camp believes that the Radicals would have attempted to impeach Lincoln, just as they did to his successor, Andrew Johnson, in 1868.[66][77]

Johnson's presidential Reconstruction

1865–1869

Northern anger over the assassination of Lincoln and the immense human cost of the war led to demands for punitive policies. Vice President Andrew Johnson had taken a hard line and spoke of hanging Confederates, but when he succeeded Lincoln as president, Johnson took a much softer position, pardoning many Confederate leaders and former Confederates.[78] Former Confederate President Jefferson Davis was held in prison for two years, but other Confederate leaders were not. There were no trials on charges of treason. Only one person—Captain Henry Wirz, the commandant of the prison camp in Andersonville, Georgia—was executed for war crimes. Andrew Johnson's conservative view of Reconstruction did not include the involvement of blacks or former slaves in government and he refused to heed Northern concerns when Southern state legislatures implemented Black Codes that set the status of the freedmen much lower than that of citizens.[9]

Smith argues that "Johnson attempted to carry forward what he considered to be Lincoln's plans for Reconstruction."[79] McKitrick says that in 1865 Johnson had strong support in the Republican Party, saying: "It was naturally from the great moderate sector of Unionist opinion in the North that Johnson could draw his greatest comfort."[80] Billington says: "One faction, the moderate Republicans under the leadership of Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, favored a mild policy toward the South."[81] Lincoln biographers Randall and Current argued that:

It is likely that had he lived, Lincoln would have followed a policy similar to Johnson's, that he would have clashed with congressional Radicals, that he would have produced a better result for the freedmen than occurred, and that his political skills would have helped him avoid Johnson's mistakes.[82]

Historians generally agree that President Johnson was an inept politician who lost all his advantages by unskilled maneuvering. He broke with Congress in early 1866 and then became defiant and tried to block enforcement of Reconstruction laws passed by the U.S. Congress. He was in constant conflict constitutionally with the Radicals in Congress over the status of freedmen and whites in the defeated South.[83] Although resigned to the abolition of slavery, many former Confederates were unwilling to accept both social changes and political domination by former slaves. In the words of Benjamin Franklin Perry, President Johnson's choice as the provisional governor of South Carolina: "First, the Negro is to be invested with all political power, and then the antagonism of interest between capital and labor is to work out the result."[84]

However, the fears of the mostly conservative planter elite and other leading white citizens were partly assuaged by the actions of President Johnson, who ensured that a wholesale land redistribution from the planters to the freedmen did not occur. President Johnson ordered that confiscated or abandoned lands administered by the Freedmen's Bureau would not be redistributed to the freedmen but would be returned to pardoned owners. Land was returned that would have been forfeited under the Confiscation Acts passed by Congress in 1861 and 1862.

Freedmen and the enactment of Black Codes

Southern state governments quickly enacted the restrictive "Black Codes." However, they were abolished in 1866 and seldom had effect, because the Freedmen's Bureau (not the local courts) handled the legal affairs of freedmen.

The Black Codes indicated the plans of the Southern whites for the former slaves.[85] The freedmen would have more rights than did free blacks before the war, but they would still have only a limited set of second-class civil rights, no voting rights and no citizenship. They could not own firearms, serve on a jury in a lawsuit involving whites, or move about without employment.[86] The Black Codes outraged Northern opinion. They were overthrown by the Civil Rights Act of 1866 that gave the freedmen more legal equality (although still without the right to vote).[87]

The freedmen, with the strong backing of the Freedmen's Bureau, rejected gang-labor work patterns that had been used in slavery. Instead of gang labor, freed people preferred family-based labor groups.[88] They forced planters to bargain for their labor. Such bargaining soon led to the establishment of the system of sharecropping, which gave the freedmen greater economic independence and social autonomy than gang labor. However, because they lacked capital and the planters continued to own the means of production (tools, draft animals, and land), the freedmen were forced into producing cash crops (mainly cotton) for the land-owners and merchants, and they entered into a crop-lien system. Widespread poverty, disruption to an agricultural economy too dependent on cotton, and the falling price of cotton, led within decades to the routine indebtedness of the majority of the freedmen, and the poverty of many planters.[89]

Northern officials gave varying reports on conditions for the freedmen in the South. One harsh assessment came from Carl Schurz, who reported on the situation in the states along the Gulf Coast. His report documented dozens of extra-judicial killings and claimed that hundreds or thousands more African Americans were killed.[90]

The number of murders and assaults perpetrated upon Negroes is very great; we can form only an approximative estimate of what is going on in those parts of the South which are not closely garrisoned, and from which no regular reports are received, by what occurs under the very eyes of our military authorities. As to my personal experience, I will only mention that during my two days sojourn at Atlanta, one Negro was stabbed with fatal effect on the street, and three were poisoned, one of whom died. While I was at Montgomery, one Negro was cut across the throat evidently with intent to kill, and another was shot, but both escaped with their lives. Several papers attached to this report give an account of the number of capital cases that occurred at certain places during a certain period of time. It is a sad fact that the perpetration of those acts is not confined to that class of people which might be called the rabble.[91]

The report included sworn testimony from soldiers and officials of the Freedmen's Bureau. In Selma, Alabama, Major J. P. Houston noted that whites who killed 12 African Americans in his district never came to trial. Many more killings never became official cases. Captain Poillon described white patrols in southwestern Alabama:

who board some of the boats; after the boats leave they hang, shoot, or drown the victims they may find on them, and all those found on the roads or coming down the rivers are almost invariably murdered. The bewildered and terrified freedmen know not what to do—to leave is death; to remain is to suffer the increased burden imposed upon them by the cruel taskmaster, whose only interest is their labor, wrung from them by every device an inhuman ingenuity can devise; hence the lash and murder is resorted to intimidate those whom fear of an awful death alone cause to remain, while patrols, Negro dogs and spies, disguised as Yankees, keep constant guard over these unfortunate people.

Much of the violence that was perpetrated against African Americans was shaped by gender prejudices regarding African Americans. Black women were in a particularly vulnerable situation. To convict a white man of sexually assaulting black women in this period was exceedingly difficult.[21] The South's judicial system had been wholly re-figured to make one of its primary purposes the coercion of African Americans to comply with the social customs and labor demands of whites. Trials were discouraged and attorneys for black misdemeanor defendants were difficult to find. The goal of county courts was a fast, uncomplicated trial with a resulting conviction. Most blacks were unable to pay their fines or bail, and "the most common penalty was nine months to a year in a slave mine or lumber camp."[92] The South's judicial system was rigged to generate fees and claim bounties, not to ensure public protection. Black women were socially perceived as sexually avaricious and since they were portrayed as having little virtue, society held that they could not be raped.[93] One report indicates two freed women, Frances Thompson and Lucy Smith, describe their violent sexual assault during the Memphis Riots of 1866.[94] However, black women were vulnerable even in times of relative normalcy. Sexual assaults on African American women were so pervasive, particularly on the part of their white employers, that black men sought to reduce the contact between white males and black females by having the women in their family avoid doing work that was closely overseen by whites.[95] Black men were construed as being extremely sexually aggressive and their supposed or rumored threats to white women were often used as a pretext for lynching and castrations.[21]

Moderate responses

During fall 1865, out of response to the Black Codes and worrisome signs of Southern recalcitrance, the Radical Republicans blocked the readmission of the former rebellious states to the Congress. Johnson, however, was content with allowing former Confederate states into the Union as long as their state governments adopted the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery. By December 6, 1865, the amendment was ratified and Johnson considered Reconstruction over. Johnson was following the moderate Lincoln presidential Reconstruction policy to get the states readmitted as soon as possible.[96]

Congress, however, controlled by the Radicals, had other plans. The Radicals were led by Charles Sumner in the Senate and Thaddeus Stevens in the House of Representatives. Congress, on December 4, 1865, rejected Johnson's moderate presidential Reconstruction, and organized the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, a 15-member panel to devise Reconstruction requirements for the Southern states to be restored to the Union.[96]

In January 1866, Congress renewed the Freedmen's Bureau; however, Johnson vetoed the Freedmen's Bureau Bill in February 1866. Although Johnson had sympathy for the plight of the freedmen, he was against federal assistance. An attempt to override the veto failed on February 20, 1866. This veto shocked the congressional Radicals. In response, both the Senate and House passed a joint resolution not to allow any senator or representative seat admittance until Congress decided when Reconstruction was finished.[96]

Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, leader of the moderate Republicans, took affront to the Black Codes. He proposed the first Civil Rights Act, because the abolition of slavery was empty if:

laws are to be enacted and enforced depriving persons of African descent of privileges which are essential to freemen. . . . A law that does not allow a colored person to go from one county to another, and one that does not allow him to hold property, to teach, to preach, are certainly laws in violation of the rights of a freeman... The purpose of this bill is to destroy all these discriminations.[97]

The key to the bill was the opening section:

All persons born in the United States . . . are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States; and such citizens of every race and color, without regard to any previous condition of slavery . . . shall have the same right in every State . . . to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties and to none other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom to the Contrary notwithstanding.

The bill did not give freedmen the right to vote. Congress quickly passed the Civil Rights bill; the Senate on February 2 voted 33–12; the House on March 13 voted 111–38.

Johnson's vetoes

Although strongly urged by moderates in Congress to sign the Civil Rights bill, Johnson broke decisively with them by vetoing it on March 27, 1866. His veto message objected to the measure because it conferred citizenship on the freedmen at a time when 11 out of 36 states were unrepresented and attempted to fix by federal law "a perfect equality of the white and black races in every state of the Union." Johnson said it was an invasion by federal authority of the rights of the states; it had no warrant in the Constitution and was contrary to all precedents. It was a "stride toward centralization and the concentration of all legislative power in the national government."[99]

The Democratic Party, proclaiming itself the party of white men, North and South, supported Johnson.[100] However, the Republicans in Congress overrode his veto (the Senate by the close vote of 33–15, and the House by 122-41) and the civil rights bill became law. Congress also passed a watered-down Freedmen's Bureau bill; Johnson quickly vetoed as he had done to the previous bill. Once again, however, Congress had enough support and overrode Johnson's veto.[101]

The last moderate proposal was the Fourteenth Amendment, whose principal drafter was Representative John Bingham. It was designed to put the key provisions of the Civil Rights Act into the Constitution, but it went much further. It extended citizenship to everyone born in the United States (except Indians on reservations), penalized states that did not give the vote to freedmen, and most important, created new federal civil rights that could be protected by federal courts. It guaranteed the federal war debt would be paid (and promised the Confederate debt would never be paid). Johnson used his influence to block the amendment in the states since three-fourths of the states were required for ratification (the amendment was later ratified). The moderate effort to compromise with Johnson had failed, and a political fight broke out between the Republicans (both Radical and moderate) on one side, and on the other side, Johnson and his allies in the Democratic Party in the North, and the conservative groupings (which used different names) in each Southern state.

Radical Reconstruction

Concerned that President Johnson viewed Congress as an "illegal body" and wanted to overthrow the government, Republicans in Congress took control of Reconstruction policies after the election of 1866.[102] Johnson ignored the policy mandate, and he openly encouraged Southern states to deny ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment (except for Tennessee, all former Confederate states did refuse to ratify, as did the border states of Delaware, Maryland, and Kentucky). Radical Republicans in Congress, led by Stevens and Sumner, opened the way to suffrage for male freedmen. They were generally in control, although they had to compromise with the moderate Republicans (the Democrats in Congress had almost no power). Historians refer to this period as "Radical Reconstruction" or "congressional Reconstruction."[103] The business spokesmen in the North generally opposed Radical proposals. Analysis of 34 major business newspapers showed that 12 discussed politics, and only one, Iron Age, supported radicalism. The other 11 opposed a "harsh" Reconstruction policy, favored the speedy return of the Southern states to congressional representation, opposed legislation designed to protect the freedmen, and deplored the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson.[104]

The South's white leaders, who held power in the immediate postwar era before the vote was granted to the freedmen, renounced secession and slavery, but not white supremacy. People who had previously held power were angered in 1867 when new elections were held. New Republican lawmakers were elected by a coalition of white Unionists, freedmen and Northerners who had settled in the South. Some leaders in the South tried to accommodate new conditions.

Constitutional amendments

Three constitutional amendments, known as the Reconstruction amendments, were adopted. The Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery was ratified in 1865. The Fourteenth Amendment was proposed in 1866 and ratified in 1868, guaranteeing United States citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States and granting them federal civil rights. The Fifteenth Amendment, proposed in late February 1869, and passed in early February 1870, decreed that the right to vote could not be denied because of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." Left unaffected was that states would still determine voter registration and electoral laws. The amendments were directed at ending slavery and providing full citizenship to freedmen. Northern congressmen believed that providing black men with the right to vote would be the most rapid means of political education and training.

Many blacks took an active part in voting and political life, and rapidly continued to build churches and community organizations. Following Reconstruction, white Democrats and insurgent groups used force to regain power in the state legislatures, and pass laws that effectively disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites in the South. From 1890 to 1910, Southern states passed new state constitutions that completed the disenfranchisement of blacks. U.S. Supreme Court rulings on these provisions upheld many of these new Southern state constitutions and laws, and most blacks were prevented from voting in the South until the 1960s. Full federal enforcement of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments did not reoccur until after passage of legislation in the mid-1960s as a result of the civil rights movement.

For details, see:

- Redemption (United States history)

- Disenfranchisement after the Reconstruction Era

- Jim Crow laws

- United States v. Cruikshank (1875),[105][106] related to the Colfax Massacre

- Posse Comitatus Act (1878)

- Civil Rights Cases (1883)

- Civil rights movement (1896–1954)

- Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

- Williams v. Mississippi (1898)

- Giles v. Harris (1903)

Statutes

The Reconstruction Acts as originally passed, were initially called "An act to provide for the more efficient Government of the Rebel States." The legislation was enacted by the 39th Congress, on March 2, 1867. It was vetoed by President Johnson, and the veto overridden by a two-thirds majority, in both the House and the Senate, the same day. Congress also clarified the scope of the federal writ of habeas corpus to allow federal courts to vacate unlawful state court convictions or sentences in 1867 (28 U.S.C. § 2254).

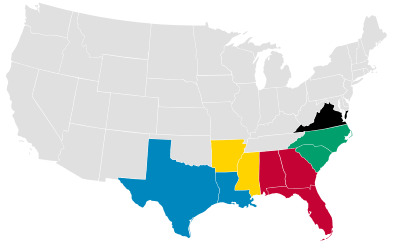

Military Reconstruction

With the Radicals in control, Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts on July 19, 1867. The first Reconstruction Act, authored by Oregon Sen. George Henry Williams, a Radical Republican, placed 10 of the former Confederate states—all but Tennessee—under military control, grouping them into five military districts:[107]

- First Military District: Virginia, under General John Schofield

- Second Military District: North Carolina and South Carolina, under General Daniel Sickles

- Third Military District: Georgia, Alabama, and Florida, under Generals John Pope and George Meade

- Fourth Military District: Arkansas and Mississippi, under General Edward Ord

- Fifth Military District: Texas and Louisiana, under Generals Philip Sheridan and Winfield Scott Hancock

20,000 U.S. troops were deployed to enforce the act.

The four border states that had not joined the Confederacy were not subject to military Reconstruction. West Virginia, which had seceded from Virginia in 1863, and Tennessee, which had already been re-admitted in 1866, were not included in the military districts.

The 10 Southern state governments were re-constituted under the direct control of the United States Army. One major purpose was to recognize and protect the right of African Americans to vote.[108] There was little to no combat, but rather a state of martial law in which the military closely supervised local government, supervised elections, and tried to protect office holders and freedmen from violence.[109] Blacks were enrolled as voters; former Confederate leaders were excluded for a limited period.[110] No one state was entirely representative. Randolph Campbell describes what happened in Texas:[111]

The first critical step . . . was the registration of voters according to guidelines established by Congress and interpreted by Generals Sheridan and Charles Griffin. The Reconstruction Acts called for registering all adult males, white and black, except those who had ever sworn an oath to uphold the Constitution of the United States and then engaged in rebellion. . . . Sheridan interpreted these restrictions stringently, barring from registration not only all pre-1861 officials of state and local governments who had supported the Confederacy but also all city officeholders and even minor functionaries such as sextons of cemeteries. In May Griffin . . . appointed a three-man board of registrars for each county, making his choices on the advice of known scalawags and local Freedmen's Bureau agents. In every county where practicable a freedman served as one of the three registrars. . . . Final registration amounted to approximately 59,633 whites and 49,479 blacks. It is impossible to say how many whites were rejected or refused to register (estimates vary from 7,500 to 12,000), but blacks, who constituted only about 30 percent of the state's population, were significantly over-represented at 45 percent of all voters.[112]

State constitutional conventions: 1867–69

The 11 Southern states held constitutional conventions giving black men the right to vote,[113] where the factions divided into the Radical, conservative, and in-between delegates.[114] The Radicals were a coalition: 40% were Southern white Republicans ("scalawags"); 25% were white carpetbaggers, and 34% were black.[115] Scalawags wanted to disenfranchise all of the traditional white leadership class, but moderate Republican leaders in the North warned against that, and black delegates typically called for universal voting rights.[116][117] The carpetbaggers inserted provisions designed to promote economic growth, especially financial aid to rebuild the ruined railroad system.[118][119] The conventions set up systems of free public schools funded by tax dollars, but did not require them to be racially integrated.[120]

Until 1872, most former Confederate or prewar Southern office holders were disqualified from voting or holding office; all but 500 top Confederate leaders were pardoned by the Amnesty Act of 1872.[121] "Proscription" was the policy of disqualifying as many ex-Confederates as possible. It appealed to the scalawag element. For example, in 1865 Tennessee had disenfranchised 80,000 ex-Confederates.[122] However, proscription was soundly rejected by the black element, which insisted on universal suffrage.[123] The issue would come up repeatedly in several states, especially in Texas and Virginia. In Virginia, an effort was made to disqualify for public office every man who had served in the Confederate Army even as a private, and any civilian farmer who sold food to the Confederate States Army.[124][125] Disenfranchising Southern whites was also opposed by moderate Republicans in the North, who felt that ending proscription would bring the South closer to a republican form of government based on the consent of the governed, as called for by the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Strong measures that were called for in order to forestall a return to the defunct Confederacy increasingly seemed out of place, and the role of the United States Army and controlling politics in the state was troublesome. Historian Mark Summers states that increasingly "the disenfranchisers had to fall back on the contention that denial of the vote was meant as punishment, and a lifelong punishment at that... Month by month, the un-republican character of the regime looked more glaring."[126]

Politics

Grant: the Radical President

During the Civil War, many in the North believed that fighting for the Union was a noble cause–for the preservation of the Union and the end of slavery. After the war ended, with the North victorious, the fear among Radicals was that President Johnson too quickly assumed that slavery and Confederate nationalism were dead and that the Southern states could return. The Radicals sought out a candidate for president who represented their viewpoint.[127]

In 1868, the Republicans unanimously chose Ulysses S. Grant as their presidential candidate. Grant won favor with the Radicals after he allowed Edwin Stanton, a Radical, to be reinstated as secretary of war. As early as 1862, during the Civil War, Grant had appointed the Ohio military chaplain John Eaton to protect and gradually incorporate refugee slaves in west Tennessee and northern Mississippi into the Union war effort and pay them for their labor. It was the beginning of his vision for the Freedmen's Bureau.[128] Grant opposed President Johnson by supporting the Reconstruction Acts passed by the Radicals.[129][130]

Immediately upon inauguration in 1869, Grant bolstered Reconstruction by prodding Congress to readmit Virginia, Mississippi, and Texas into the Union, while ensuring their state constitutions protected every citizen's voting rights.[131] Grant met with prominent black leaders for consultation, and signed a bill into law that guaranteed equal rights to both blacks and whites in Washington, D.C.[131]

In Grant's two terms he strengthened Washington's legal capabilities to directly intervene to protect citizenship rights even if the states ignored the problem.[133] He worked with Congress to create the Department of Justice and office of solicitor general, led by Attorney General Amos Akerman and the first Solicitor General Benjamin Bristow. Congress passed three powerful Enforcement Acts in 1870–71. These were criminal codes which protected the freedmen's right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protection of laws. Most important, they authorized the federal government to intervene when states did not act. Grant's new Justice Department prosecuted thousands of Klansmen under the tough new laws. Grant sent federal troops to nine South Carolina counties to suppress Klan violence in 1871. Grant supported passage of the Fifteenth Amendment stating that no state could deny a man the right to vote on the basis of race. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875 giving people access to public facilities regardless of race.[134]

To counter vote fraud in the Democratic stronghold of New York City, Grant sent in tens of thousands of armed, uniformed federal marshals and other election officials to regulate the 1870 and subsequent elections. Democrats across the North then mobilized to defend their base and attacked Grant's entire set of policies.[135] On October 21, 1876, President Grant deployed troops to protect black and white Republican voters in Petersburg, Virginia.[136]

Grant's support from Congress and the nation declined due to scandals within his administration and the political resurgence of the Democrats in the North and South. By 1870, most Republicans felt the war goals had been achieved, and they turned their attention to other issues such as economic policies.[137]

Congressional investigation (1871–1872)

On April 20, 1871, the U.S. Congress launched a 21-member investigation committee on the status of the Southern Reconstruction states: North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. Congressional members on the committee included Rep. Benjamin Butler, Sen. Zachariah Chandler, and Sen. Francis P. Blair. Subcommittee members traveled into the South to interview the people living in their respective states. Those interviewed included top-ranking officials, such as Wade Hampton III, former South Carolina Gov. James L. Orr, and Nathan Bedford Forrest, a former Confederate general and prominent Ku Klux Klan leader (Forrest denied in his congressional testimony being a member). Other Southerners interviewed included farmers, doctors, merchants, teachers, and clergymen. The committee heard numerous reports of white violence against blacks, while many whites denied Klan membership or knowledge of violent activities. The majority report by Republicans concluded that the government would not tolerate any Southern "conspiracy" to resist violently the congressional Reconstruction. The committee completed its 13-volume report in February 1872. While Grant had been able to suppress the KKK through the Enforcement Acts, other paramilitary insurgents organized, including the White League in 1874, active in Louisiana; and the Red Shirts, with chapters active in Mississippi and the Carolinas. They used intimidation and outright attacks to run Republicans out of office and repress voting by blacks, leading to white Democrats regaining power by the elections of the mid-to-late 1870s.[138]

African American officeholders

Republicans took control of all Southern state governorships and state legislatures, except for Virginia.[139] The Republican coalition elected numerous African Americans to local, state, and national offices; though they did not dominate any electoral offices, black men as representatives voting in state and federal legislatures marked a drastic social change. At the beginning of 1867, no African American in the South held political office, but within three or four years "about 15 percent of the officeholders in the South were black—a larger proportion than in 1990." Most of those offices were at the local level.[140] In 1860 blacks constituted the majority of the population in Mississippi and South Carolina, 47% in Louisiana, 45% in Alabama, and 44% in Georgia and Florida,[141] so their political influence was still far less than their percentage of the population.

About 137 black officeholders had lived outside the South before the Civil War. Some who had escaped from slavery to the North and had become educated returned to help the South advance in the postwar era. Others were free blacks before the war, who had achieved education and positions of leadership elsewhere. Other African American men elected to office were already leaders in their communities, including a number of preachers. As happened in white communities, not all leadership depended upon wealth and literacy.[142][143]

| Race of delegates to 1867 state constitutional conventions[144] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | White | Black | % White | Statewide white population (% in 1870)[145] |

| Virginia | 80 | 25 | 76 | 58 |

| North Carolina | 107 | 13 | 89 | 63 |

| South Carolina | 48 | 76 | 39 | 41 |

| Georgia | 133 | 33 | 80 | 54 |

| Florida | 28 | 18 | 61 | 51 |

| Alabama | 92 | 16 | 85 | 52 |

| Mississippi | 68 | 17 | 80 | 46 |

| Louisiana | 25 | 44 | 36 | 50 |

| Texas | 81 | 9 | 90 | 69 |

There were few African Americans elected or appointed to national office. African Americans voted for both white and black candidates. The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution guaranteed only that voting could not be restricted on the basis of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. From 1868 on, campaigns and elections were surrounded by violence as white insurgents and paramilitaries tried to suppress the black vote, and fraud was rampant. Many congressional elections in the South were contested. Even states with majority African American populations often elected only one or two African American representatives to Congress. Exceptions included South Carolina; at the end of Reconstruction, four of its five congressmen were African Americans.[146]

| African Americans in Office 1870–1876[147] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | State Legislators | U.S. Senators | U.S. Congressmen |

| Alabama | 69 | 0 | 4 |

| Arkansas | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Florida | 30 | 0 | 1 |

| Georgia | 41 | 0 | 1 |

| Louisiana | 87 | 0 | 1* |

| Mississippi | 112 | 2 | 1 |

| North Carolina | 30 | 0 | 1 |

| South Carolina | 190 | 0 | 6 |

| Tennessee | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Texas | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Virginia | 46 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 633 | 2 | 15 |

Social and economic factors

Religion

Freedmen were very active in forming their own churches, mostly Baptist or Methodist, and giving their ministers both moral and political leadership roles. In a process of self-segregation, practically all blacks left white churches so that few racially integrated congregations remained (apart from some Catholic churches in Louisiana). They started many new black Baptist churches and soon, new black state associations.

Four main groups competed with each other across the South to form new Methodist churches composed of freedmen. They were the African Methodist Episcopal Church; the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, both independent black denominations founded in Philadelphia and New York, respectively; the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (which was sponsored by the white Methodist Episcopal Church, South) and the well-funded Methodist Episcopal Church (Northern white Methodists). The Methodist Church had split before the war due to disagreements about slavery.[148][149] By 1871 the Northern Methodists had 88,000 black members in the South, and had opened numerous schools for them.[150]