Modoc War

The Modoc War, or the Modoc Campaign (also known as the Lava Beds War), was an armed conflict between the Native American Modoc people and the United States Army in northeastern California and southeastern Oregon from 1872 to 1873.[3] Eadweard Muybridge photographed the early part of the US Army's campaign.

| Modoc War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Modoc | United States | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Kintpuash Scarface Charley Shaknasty Jim |

Frank Wheaton John Green Reuben Benard Alvan Gillem Edwin Cooley Mason Jefferson C. Davis Edward Canby † Donald McKay Billy Chinook | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 120 warriors[1] |

1,000 infantry, scouts and cavalry[1] 2 howitzers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

17 warriors killed[2] 39 warriors captured[2] |

73 soldiers and volunteers killed[2] 46 wounded | ||||||

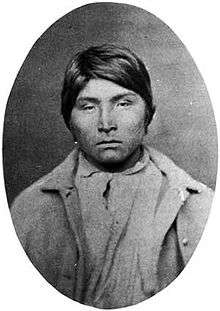

Kintpuash, also known as Captain Jack, led 52 warriors in a band of more than 150 Modoc people who left the Klamath Reservation. Occupying defensive positions throughout the lava beds south of Tule Lake (in present-day Lava Beds National Monument), those few warriors resisted for months the more numerous United States Army forces sent against them, which were reinforced with artillery. In April 1873 at a peace commission meeting, Captain Jack and others killed General Edward Canby and Rev. Eleazer Thomas, and wounded two others, mistakenly believing this would encourage the Americans to leave. The Modoc fled back to the lava beds. After U.S. forces were reinforced, some Modoc warriors surrendered and Captain Jack and the last of his band were captured. Jack and five warriors were tried for the murders of the two peace commissioners. Jack and three warriors were executed and two others sentenced to life in prison.

The remaining 153 Modoc of the band were sent to Indian Territory (pre-statehood Oklahoma), where they were held as prisoners of war until 1909, settled on reservation land with the Shawnee. Some at that point were allowed to return to the Klamath Reservation in Oregon. Most Modoc (and their descendants) stayed in what became the state of Oklahoma. They achieved separate federal recognition and were granted some land in Oklahoma. There are two federally recognized Modoc tribes: in Oregon and Oklahoma.

Events leading up to the war

The first known explorers from the United States to go through the Modoc country were John Charles Frémont together with Kit Carson and Billy Chinook in 1843. On the night of May 9, 1846, Frémont received a message brought to him by Lieutenant Archibald Gillespie, from President James Polk about the possibility of war with Mexico. Reviewing the messages, Frémont neglected the customary measure of posting a watchman for the camp. Carson was concerned but "apprehended no danger".[4] Later that night Carson was awakened by the sound of a thump. Jumping up, he saw his friend and fellow trapper Basil Lajeunesse sprawled in blood. He sounded an alarm and immediately the camp realized they were under attack by Native Americans, estimated to be several dozen in number. By the time the assailants were beaten off, two other members of Frémont's group were dead. The one dead attacker was judged to be a Klamath Lake native. Frémont's group fell into "an angry gloom."[5]

In retaliation, Frémont attacked a Klamath Tribe fishing village named Dokdokwas, that most likely had nothing to do with the attack, at the junction of the Williamson River and Klamath Lake, on May 10, 1846.[6] Accounts by scholars vary, but they agree that the attack completely destroyed the village structures; Sides reports the expedition killed women and children as well as warriors.[7]

The tragedy of Dokdokwas is deepened by the fact that most scholars now agree that Frémont and Carson, in their blind vindictiveness, probably chose the wrong tribe to lash out against: In all likelihood the band of native Americans that had killed [Frémont's three men] were from the neighboring Modoc ... The Klamaths were culturally related to the Modocs, but the two tribes were bitter enemies.[8]

Although most of the "49ers" missed the Modoc country, in March 1851 Abraham Thompson, a mule train packer, discovered gold near Yreka while traveling along the Siskiyou Trail from southern Oregon. The discovery sparked the California Gold Rush area to expand from the Sierra Nevada into Northeastern California. By April 1851, 2,000 miners had arrived in "Thompson's Dry Diggings" through the southern route of the old Emigrant Trail to test their luck, which took them straight through Modoc territory.[9]

First hostilities

Although the Modoc initially had no trouble with Americans, after the murders of settlers in a raid by the Pit River Tribe, an American militia unit, not familiar with the Indian peoples, retaliated by attacking an innocent Modoc village, killing men, women and children.[10] (Kintpuash, the future chief also known as Captain Jack, survived the attack but lost some of his family.) To try to end the American encroachment, some Modoc chose to attack the next whites they encountered. In September 1852 the Modoc attacked a wagon train of some 65 men, women, and children on their way to California.[11]

One badly wounded man escaped to the Oregon settlements in Willamette Valley and told of the attack. His report spread quickly and Oregon volunteers who later reached the scene, reported bodies of men, women and children mutilated and scattered for more than a mile along the lake shore and their wagons plundered and burned.[11] The location became known as Bloody Point.[10][12] In another round of retaliation, California militia led by an Indian fighter named Ben Wright killed 41 Modoc at a peace parley.[10] John Schonchin, the brother of the Modoc chief, was one of the Indians who escaped.

Great Treaty of Council Grove

Rounds of hostilities continued in the area as American settlers continued to encroach on Modoc land and urged the government to take over the territory. Warriors of the Klamath and the Yahooskin also attacked settlers and migrants in efforts to repulse them. In 1864 the United States and the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin band—over 1000 Indians, mostly Klamath—signed a treaty, by which the Indians ceded millions of acres of lands and the US established the Klamath Reservation, within the boundaries of present-day Oregon. Under the treaty terms, the Modoc, with Old Chief Schonchin as their leader, gave up their lands in the Lost River, Tule Lake and Lower Klamath Lake regions of California, and moved to a reservation in the Upper Klamath River Valley. In return, the Indians would receive food, blankets, and clothing for as many years as would be required to establish themselves.[9] Allen David signed for the Klamath, while Old Schonchin and Kintpuash for the Modoc. Looking around for something to give emphasis to his pledge, Schonchin pointed to the distant butte and dramatically declared, "That mountain shall fall, before Schonchin will again raise his hand against his white brother."[11] The old chief kept his word, although his brother and Kintpuash repudiated signing the treaty and left the reservation with a few followers.

Captain Jack

While the old Modoc chief remained in the reservation, Kintpuash returned to Lost River and led an abusive harassment against the white settlers who had occupied the area. The small Modoc group of about 43 Indians demanded rent for the occupation of their land, which most settlers paid. After a few attempts to negotiate in behalf of the complaining settlers, including failed attempts by Agent Lindsay Applegate in 1864–6[13] and Superintendent Huntington in 1867, the Modoc finally relocated in 1869 following a council between Kintpuash (also known as Captain Jack); Alfred B. Meacham, the US Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon that replaced Huntington; O.C. Knapp, the US Indian agent on the reservation; Ivan D. Applegate, sub-agent at Yainax on the reservation; and Dr. William.C. McKay. Meacham was from Oregon, and knew Captain Jack and the Modoc.

When soldiers suddenly appeared at the meeting, the Modoc warriors fled, leaving behind their women and children. Meacham placed the women and children in wagons and started for the reservation. He allowed "Queen Mary", Captain Jack's sister, to go meet with Captain Jack to persuade him to move to the reservation. She succeeded. Once on the reservation, Captain Jack and his band prepared to make their permanent home at Modoc Point.

Mistreatment by the Klamath

Shortly after the Modoc started building their homes, however, the Klamath, longtime rivals, began to steal the Modoc lumber. The Modoc complained, but the US Indian agent could not protect them against the Klamath. Captain Jack's band moved to another part of the reservation. Several attempts were made to find a suitable location, but the Klamath continued to harass the band.

In 1870, Captain Jack and his band of nearly 200 left the reservation and returned to Lost River. During the months that his band had been on the reservation, a number of settlers had taken up former Modoc land in the Lost River region.

Return to Lost River

Acknowledging the bad feeling between the Modoc and the Klamath, Meacham recommended to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C. that Captain Jack's Modoc band be given a separate reservation at Yainax, in the lower southern part of the reservation. Pending a decision, Meacham instructed Captain Jack to remain at Clear Lake. Oregon settlers complained that Modoc warriors roamed the countryside raiding the homesteads; they petitioned Meacham to return the Modoc to the Klamath Reservation. In part, the Modoc raided for food; the US did not adequately supply them. Captain Jack and his band did better in their old territory with hunting.

Failure of US to respond to Modoc

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs never responded to Meacham's request for a separate reservation for the Modoc. After hearing more complaints from settlers, Meacham instead requested General Edward Canby, Commanding General of the Department of the Columbia, to move Captain Jack's band to Yainax on the Klamath Reservation, his recommended site for their use. Canby forwarded Meacham's request to General Schofield, Commanding General of the Pacific, suggesting that before using force, peaceful efforts should be made. Jack had asked to talk to Meacham, but he sent his brother John Meacham in his place.[14]

In the middle of the crisis, the Commission of Indian Affairs replaced Meacham, appointing T. B. Odeneal as Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon.[14][15] He "knew almost nothing of the background of the situation and had never met Jack or the Modocs" but was charged with "getting the Modocs to leave Lost River."[14] In turn, Odeneal appointed a new US Indian agent, who was also unfamiliar with the parties and conditions.

On April 3, 1872, Major Elmer Otis held a council with Captain Jack at Lost River Gap, near what is now Olene, Oregon. At the council, Major Otis presented Captain Jack with some settlers who complained about the behavior of Jack's men. Captain Jack countered that the Modoc were abused and unjustly accused of crimes which other Indians had committed.

Although the council's results were inconclusive, Otis resolved to remove Jack's band of Modoc to the Klamath Reservation. As he needed reinforcements, he recommended waiting until later in the year, when he could put the Modoc at a disadvantage.[16]

On April 12, the Commission of Indian Affairs directed US Superintendent T. B. Odeneal[15] to move Captain Jack and his Modoc to the reservation if practicable. He was to ensure the tribe was protected from the Klamath.

On May 14, Odeneal sent Ivan D. Applegate and L. S. Dyar to arrange for a council with Captain Jack, which the latter refused. On July 6, 1872, the US Commissioner of Indian Affairs repeated his direction to Superintendent Odeneal to move Captain Jack and his band to the Klamath Reservation, peacefully if possible, but forcibly if necessary. Minor skirmishes occurred during the summer and early fall, but some of the settlers in California were sympathetic to the Modoc, as they had gotten along well with them before. The Modoc felt mistreated.

Battle of Lost River

On November 27, Superintendent Odeneal requested Major John Green, commanding officer at Fort Klamath, to furnish sufficient troops to compel Captain Jack to move to the reservation. On November 28 Captain James Jackson, commanding 40 troops, left Fort Klamath for Captain Jack's camp on Lost River. The troops, reinforced by citizens from Linkville (now Klamath Falls, Oregon) and by a band of militiamen arrived in Jack's camp on Lost River about a mile above Emigrant Crossing (now Merrill, Oregon) on November 29.

Wishing to avoid conflict, Captain Jack agreed to go to the reservation, but the situation became tense when Jackson demanded that the Modoc chief surrender his weapons. Although Captain Jack had never fought the Army, he was alarmed at this command, but he finally agreed to put down his weapons. The rest of the Modoc warriors began to follow his lead.

Suddenly an argument erupted between Modoc warrior Scarfaced Charley and Lieutenant Frazier A. Boutelle, of company B, 1st Cavalry. They drew their revolvers and shot at each other, both missing. The rest of the Modocs scrambled for their weapons, and briefly fought before fleeing toward California. After driving the remaining Modoc from the camp, Captain Jackson ordered a retreat to await reinforcements. One soldier had been killed and seven wounded in the encounter; the Modoc lost two killed and three wounded.

A small band of Modoc under Hooker Jim retreated from the battlefield to the Lava Beds south of Tule Lake. In attacks on November 29 and November 30, they killed a total of 18 settlers.

Accounts vary regarding the first clash. One version: that the soldiers and militia had gotten drunk in Klamath Falls and arrived at the Lost River camp disorganized and were outfought; that, furthermore, the militia arrived last and retreated first, with one casualty; and that the Army did not drive the Modoc away. This version claimed that some warriors held their ground while the women and children loaded their boats and paddled south; that Scarfaced Charley, who spoke good English, was foul-tempered from lack of sleep, because he'd been gambling all night and was possibly drunk—but, since there was a warrant out for his arrest on a false murder charge, he wasn't going to go quietly. The official report, however, concealed that the operation had been badly managed, as Captain Jackson later admitted.

Fortifying the Stronghold

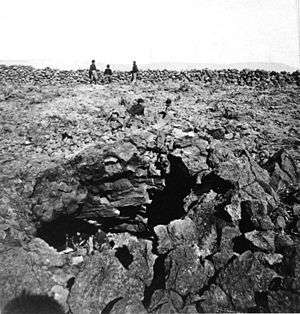

For some months, Captain Jack had boasted that in the event of war, he and his band could successfully defend themselves in an area in the lava beds on the south shore of Tule Lake. The Modoc retreated there after the Battle of Lost River. Today it is called Captain Jack's Stronghold. The Modoc took advantage of the lava ridges, cracks, depressions, and caves, all such natural features being ideal from the standpoint of defense. At the time the 52 Modoc warriors occupied the Stronghold, Tule Lake bounded the Stronghold on the north and served as a source of water.

On December 21, a Modoc party scouting from the Stronghold attacked an ammunition wagon at Land's Ranch. By January 15, 1873, the U.S. Army had 400 troops in the field near the Lava Beds. The greatest concentration of troops was at Van Brimmer's ranch, 12 miles west of the Stronghold. Troops were also stationed at Land's ranch, 10 miles east of the Stronghold. Col. Frank Wheaton was in command of all troops, including regular army as well as volunteer companies from California and Oregon.

On January 16, troops from Land's ranch, commanded by Col. R. F. Bernard, skirmished with the Modoc near Hospital Rock.

First battle of the Stronghold

On the morning of January 17, 1873, troops advanced on the Stronghold. Hindered by fog, the soldiers never saw any Modoc. Occupying excellent positions, the Modoc repulsed troops advancing from the west and east. A general retreat of troops was ordered at the end of the day. In the attack, the U.S. Army lost 35 men killed, and 5 officers and 20 enlisted men wounded. Captain Jack's band included approximately 150 Modoc, including women and children. Of that number, there were only 52 warriors. The Modoc suffered no casualties in the fighting, as they had the advantage of terrain and local knowledge over the militia.

Peace Commission appointed

On January 25, Columbus Delano, Secretary of the Interior, appointed a Peace Commission to negotiate with Captain Jack. The Commission consisted of Alfred B. Meacham, the former superintendent for Oregon as chairman; Jesse Applegate, and Samuel Case. General Edward Canby, commander in the Pacific Northwest, was appointed to serve the Commission as counselor. Frank and Toby Riddle were appointed as interpreters.

On February 19, the Peace Commission held its first meeting at Fairchild's ranch, west of the lava beds. A messenger was sent to arrange a meeting with Captain Jack. He agreed that if the commission would send John Fairchild and Bob Whittle, two settlers, to the edge of the lava beds he would talk to them. When Fairchild and Whittle went to the lava beds, Captain Jack told them he would talk with the commission if they would return with Judge Elijah Steele of Yreka as the judge had been friendly to Captain Jack.

Steele went to the Stronghold. After a night in the Stronghold, Steele returned to Fairchild's ranch and informed the Peace Commission that the Modoc were planning treachery, and that all efforts of the Commission would be useless. Meacham wired the Secretary of the Interior, informing him of Steele's opinion. The Secretary instructed Meacham to continue negotiations for peace. Judge A. M. Rosborough was added to the commission. Jesse Applegate and Samuel Case resigned and were replaced by Rev. Eleazer Thomas and L. S. Dyar.

In April, Gillem's Camp was established at the edge of the lava beds, two and one-half miles west of the Stronghold. Col. Alvan C. Gillem was placed in command of all troops, including those at Hospital Rock commanded by Col. E. C. Mason.

On April 2, the commission and Captain Jack met in the lava beds midway between the Stronghold and Gillem's Camp. At this meeting Captain Jack proposed: (1) Complete pardon of all Modoc; (2) Withdrawal of all troops; and (3) The right to select their own reservation. The Peace Commission proposed: (1) That Captain Jack and his band go to a reservation selected by the government; (2) That the Modoc guilty of killing the settlers be surrendered and tried for murder. After much discussion, the meeting broke up with no resolution.

The Modoc began to turn on Captain Jack, who still hoped for a peaceful solution. Led by Schonchin John and Hooker Jim, they put pressure on Jack to kill the peace commission. They believed that if the Americans lost their leaders, the Army would leave. They shamed Jack for his continuing negotiations by dressing him in women's clothing during council meetings. Rather than lose his position as chief of the band, Captain Jack agreed to attack the commission if no progress was made.

On April 5, Captain Jack requested a meeting with Meacham. Accompanied by John Fairchild and Judge Rosborough, with Frank and Toby Riddle serving as interpreters, Meacham met Captain Jack at the peace tent; it was erected about one mile east of Gillem's Camp. The meeting lasted several hours. Captain Jack asked for the lava beds to be given to them as a reservation. The meeting ended with no agreement. After Meacham returned to camp, he sent a message to Captain Jack, asking that he meet the commission at the peace tent on April 8. While delivering this message, the Modoc interpreter Tobey Riddle learned of the Modoc plan to kill the peace commissioners. On her return, she warned the commissioners.

On April 8, just as the commissioners were starting for the peace tent, the signal tower on the bluff above Gillem's Camp received a message; it said that the lookout had seen five Modoc warriors at the peace tent and about 20 armed Modoc hiding among the rocks nearby. The commissioners realized that the Modoc were planning an attack and decided to stay at Gillem's. Rev. Thomas insisted on arranging a date for another meeting with Captain Jack. On April 10, the commission sent a message asking Captain Jack to meet with them at the peace tent on the following morning.

Murder at the peace tent

On April 11, General Canby, Alfred B. Meacham, Rev. E. Thomas, and L. S. Dyar, with Frank and Toby Riddle as interpreters, met with Captain Jack, Boston Charley, Bogus Charley, Schonchin John, Black Jim, and Hooker Jim. After some talk, during which it became evident that the Modoc were armed, General Canby informed Captain Jack that the commission could not meet his terms until orders came from Washington.

Angrily, Schonchin John demanded Hot Creek for a reservation. Captain Jack got up and walked away a few steps. The two Modoc Brancho (Barncho) and Slolux, armed with rifles, ran forward from hiding. Captain Jack turned, giving the signal to fire. His first shot killed General Canby. Reverend Thomas fell mortally wounded. Dyar and Frank Riddle escaped by running. Meacham fell seriously wounded, but Toby Riddle saved his life and interrupted warriors intending to scalp him by yelling, "The soldiers are coming!" The Modoc warriors broke off and left.

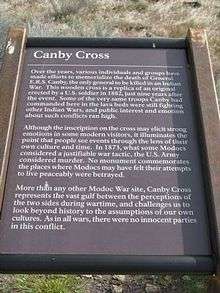

US efforts for peace ended when the Modoc killed the commissioners. Canby's Cross marks the site where Canby and Thomas died.

Second Battle of the Stronghold

The U.S. Army prepared to attack the Stronghold. On April 15 a general attack began, troops advancing from Gillem's camp on the west and Mason's camp at Hospital Rock, northeast of the Stronghold. Fighting continued throughout the day, the troops remaining in position during the night. Each advance of troops on April 16 was under heavy fire from the Modoc positions. That night the troops succeeded in cutting the Modoc off from their water supply at the shore of Tule Lake. By the morning of April 17 everything was in readiness for the final attack on the Stronghold. When the order was given to advance, the troops charged into the Stronghold.

After the fighting along the shoreline of Tule Lake on the afternoon and night of April 16, the Modoc defending the Stronghold realized that their water supply had been cut off by the troops commanding the shoreline. On April 17, before the troops had begun to charge the Stronghold, the Modoc escaped through an unguarded crevice. During the fighting at the Stronghold, April 15–17, US casualties included one officer and six enlisted men killed, and thirteen enlisted men wounded. Modoc casualties were two boys, reported to have been killed when they tried to open a cannonball and it exploded. Several Modoc women were reported to have died from sickness.

Battle of Sand Butte

On April 26, Captain Evan Thomas commanding five officers, sixty-six troops and fourteen Warm Spring Scouts left Gillem's camp on a reconnaissance of the lava beds to locate the Modoc. While they were eating lunch at the base of Sand Butte (now Hardin Butte), in a flat area surrounded by ridges, Captain Thomas and his party were attacked by 22 Modoc led by Scarfaced Charley. Some of the troops fled in disorder. Those who remained to fight were either killed or wounded. US casualties included four officers killed and two wounded, one dying within a few days, and 13 enlisted men killed and 16 wounded.

Following the successful Modoc attack, many soldiers called for Col. Gillem to be removed. On May 2, Bvt. Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis, the new commander of the Department of the Columbia, reported to relieve Gillem of command, and assume control of the army in the field.

Battle of Dry Lake

At first light on May 10, the Modoc attacked an Army encampment at Dry Lake. The troops charged, routing the Modoc. Casualties among the Army included five men killed, two of whom were Warm Spring Scouts, and twelve men wounded. The Modoc reported five warriors killed. Among the five was Ellen's Man, a prominent man in the band. This was the first defeat of the Modoc in battle.

With the death of Ellen's Man, dissent arose among the Modoc, who began to split apart. A group led by Hooker Jim surrendered to the Army and agreed to help them capture Captain Jack. In return, they received amnesty for the murders of settlers at Tule Lake, Canby and Thomas.

Captain Jack, his wife, and little girl were captured by army scouts; Captain William F. Drannan, U.S. Army and Scout George Jones, U.S. Army in Langell's valley, June 4.

After the war

General Davis prepared to execute Captain Jack and his leaders, but the War Department ordered the Modoc to be held for trial. The Army took Captain Jack and his band as prisoners of war to Fort Klamath, where they arrived July 4.

Captain Jack, Schonchin John, Black Jim, Boston Charley, Brancho (Barncho) and Slolux were tried by a military court for the murders of Canby and Thomas, and attacks on Meacham and others. The six Modoc were convicted, and sentenced to death on July 8.

On September 10, President Ulysses S. Grant approved the death sentence for Captain Jack, Schonchin John, Black Jim and Boston Charley; Brancho and Slolux were committed to life imprisonment on Alcatraz. Grant ordered that the remainder of Captain Jack's band be held as prisoners of war.

On October 3, 1873, Captain Jack and his three lead warriors were hanged at Fort Klamath. The remainder of the band of Modoc Indians, consisting of 39 men, 64 women, and 60 children, as prisoners of war were sent to the Quapaw Agency in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). In 1909, after Oklahoma had become a state, members of the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma were offered the chance to return to the Klamath Reservation. Twenty-nine people returned to Oregon; the Modoc of Oregon and their descendants became part of the Klamath Tribes Confederation.

The historian Robert Utley believes that the Modoc War and the Great Sioux War a few years later, undermined public confidence in President Grant's peace policy.[17] There was renewed public sentiment to use force against the American Indians to suppress them.

Appendix to history of the Modoc War

In the First Battle of the Stronghold, January 17, 1873, there were approximately 400 Army troops in the field. The troops included U. S. Army infantry, cavalry, and howitzer units; Oregon and California volunteer companies, and some Klamath Indian Scouts. Lt. Col. Frank Wheaton commanded all troops.

In the Second Battle of the Stronghold, April 17, 1873, approximately 530 troops were engaged. These included U. S. Army infantry, cavalry, artillery and the U.S. Army Wasco Scouts from the Warm Springs Indian Reservation . The volunteer companies had withdrawn from the field. A small number of civilians were used as runners and packers. Col. Alvin C. Gillem was in command.

During the Modoc War, the Modoc had no more than 53 warriors engaged in the fighting.

The casualty lists for the Modoc War are as follows:

| Rank | Killed | Wounded |

|---|---|---|

| Officers (U.S.A.) | 7 | 4 |

| Enlisted Men | 48 | 42 |

| Civilians | 16 | 1 |

| Indian Scouts | 2 | 0 |

| TOTALS | 73 | 47 |

Including the four Modoc executed at Fort Klamath, Captain Jack's band suffered the loss of seventeen warriors killed.

The Modoc War is estimated to have cost the United States over $400,000; a very expensive war in terms of lives and dollars, considering the small number of opposing forces. In contrast, the estimated cost to purchase the land requested by the Modoc for a separate reservation was $20,000.

Battlefields of the Modoc War are among the outstanding features of the Lava Beds National Monument. These include Captain Jack's Stronghold, where numerous cracks, ridges, and knobs were used by the Modoc to defend their positions. In addition there are numerous Modoc fortified outposts, smoke-stained caves occupied by the Modoc during the months of the war, corrals in for their cattle and horses, and a war-dance ground and council area. Around the Stronghold are numerous low stone fortifications built by troops advancing on the Stronghold.

After the Modoc left the Stronghold, US troops built fortifications to protect against their possible return. The Thomas-Wright battlefield, near Hardin Butte, is a feature of the monument; as is the site of Gillem's camp, the former military cemetery, Hospital Rock, and Canby's Cross. The National Park Service provides self-guided trail maps for two walking tours of the battle field.

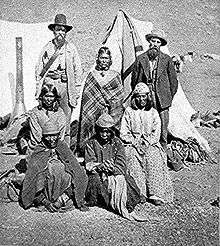

.jpg) Schonchin and Captain Jack

Schonchin and Captain Jack.jpg) Shacknasty Jim

Shacknasty Jim.jpg) Hooker Jim

Hooker Jim Boston Charley in 1873

Boston Charley in 1873 Scarface Charley

Scarface Charley

Legacy

Canby's memorial plaque and cross

A memorial plaque and a reproduction of Canby's Cross have been set up at Lava Beds National Monument outside of Tulelake. The names of all the fallen (both Modoc and US Army) are listed at Gillem's Camp; another historical marker is at the Lava Beds.

Over the years, various individuals and groups have made efforts to memorialize the death of General E.R.S. Canby, the only general to be killed in the Indian Wars. The wooden cross is a replica of an original erected by a U.S. soldier in 1882, nine years after the event. Some of the same troops whom Canby had commanded at the Lava Beds were fighting other Indian Wars, and public interest ran high.

John Yoo's torture memos

When he was the Deputy Assistant U.S. Attorney General at the Office of Legal Counsel, John Yoo cited the Supreme Court's Modoc ruling, to argue that the USA was entitled to torture captives apprehended in Afghanistan, because they, like "Indians", were not entitled to be considered lawful combatants.[18][19]

See also

- Indian Campaign Medal

- Modoc War topics index

- Native American history of California

Notes

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-08-08. Retrieved 2010-07-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-11. Retrieved 2016-06-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Beck, Warren A. and Ynez D. Hasse. The Modoc War, 1872 to 1873. Archived 2006-11-08 at the Wayback Machine California State Military Museum. (10 Feb 2008)

- This account is described in Dunlay p. 115, and Sides p. 78.

- Fremont, Memoirs, p. 492.

- John Charles Fremont Archived 2012-07-23 at the Wayback Machine Las Mariposas Civil War – TheCivilWarDays.com

- H. Sides reports the massacre included women and children. Dunlay reports that Carson said, "I directed their houses to be set on fire" and "We gave them something to remember ... the women and children we did not interfere with." (Dunlay, p.117)

- Sides, Blood and Thunder, p. 87

- Harry V. Sproull. Modoc Indian War, Lava Beds Natural History Association, 1975.

- Davis Riddle, History, pp. 28–30.

- Modoc NF History, 1945 – Chapter I, General Description Archived 2014-05-29 at the Wayback Machine United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

- "Modoc War" Archived 2006-11-08 at the Wayback Machine, California State Military Museum

- Davis Riddle, History, p. 252.

- "Keith A. Murray, The Modocs and Their War, 1965; reprint, University of Oklahoma Press, 1984, p. 71". Archived from the original on 2016-05-12. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- Don C. Fisher and John E. Doerr, Jr., "Outline of Events in the History of the Modoc War" Archived 2012-05-26 at the Wayback Machine, Nature Notes From Crater Lake, Volume 10, No. 2 – July 1937, Crater Lake Institute, accessed 1 November 2011

- Reports of the Otis Conference, 3 April 1873; and Otis to Odeneal, 11 April 1872. Archived 2014-05-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Robert Marshall Utley, Frontier regulars: the United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891 (1984) p. 206 online Archived 2016-04-28 at the Wayback Machine

-

Nick Estes (2017-01-11). "Indian Killers: Crime, Punishment, and Empire". The Red Nation. Archived from the original on 2019-05-11. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

Consider former Deputy Assistant Attorney General John Yoo’s 2003 'torture memos' in support of torture in the War on Terror. As Chickasaw scholar Jodi Byrd notes, Yoo cited the 1873 Modoc Indian Prisoners Supreme Court opinion that justified the murder of Indians by U.S. soldiers. 'All the laws and customs of civilized warfare,' the Court opined, 'may not be applicable to an armed conflict to Indian tribes on our Western frontier.' 'Indians' were legally killable because they possessed no rights as 'enemy combatants,' as it is with those now labeled “terrorist.”

-

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014). "An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States". Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807000410. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

Drawing a legal analogy between the Modoc prisoners and the Guantánamo detainees, Assistant US Attorney General Yoo employed the legal category of homo sacer—in Roman law, a person banned from society, excluded from its legal protections but still subject to the sovereign’s power. Anyone may kill a homo sacer without it being considered murder. To buttress his claim that the detainees could be denied prisoner of war status, Yoo quoted from the 1873 Modoc Indian Prisoners opinion...

References

- "Named Campaigns — Indian Wars". United States Army Center of Military History.

- Riddle, Jeff C. Davis. The Indian History of the Modoc War and the Causes that Led to It, Printed by Marnell and Co., 1914.

- Dunlay, Tom, Kit Carson and the Indians, University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

- Drannan, William F, "Thirty One Years on the Plains and in the Mountains" Rhodes & M'Clure Publishing Co. Chicago, IL 1899

- Murray, Keith A. (1984). The Modocs and Their War. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1331-6.

- Sabin, Edwin L., Kit Carson Days, vol. 1 & 2, University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

- Sides, Hampton, Blood and Thunder, Doubleday, 2006. ISBN 0-385-50777-1.

- Note: This article was adapted from a series of articles by Don C. Fisher and John E. Doerr Jr., published in the public domain Nature Notes from Crater Lake National Park, vol. x, nº 1–3, National Park Service, 1937.

Further reading

- Beeson, John. A Plea for the Indians: With Facts and Features of the Late War in Oregon. Third Edition. New York: John Beeson, 1858.

- Cothran, Boyd. Remembering the Modoc War: Redemptive Violence and the Making of American Innocence, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1-4696-1860-9

- Meacham, Alfred B. Wigwam and Warpath; or, The Royal Chief in Chains, Boston: J. P. Dale & Co., (1875), at Internet Archive, online text

- Murray, Keith A. The Modocs and Their War, Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959; reprint 1965, 1979 and more

- Quinn, Arthur. Hell With the Fire Out: A History of the Modoc War, New York: Faber and Faber, 1998

- Riddle, Jeff C. The Indian History of the Modoc War, and the Causes that Led to It, Marnell and Company, 1914, Internet Archives, online text with photos

- Smith, J. L. (2010). A Chronological History of the Oregon War, 1850 to 1878. Anchorage, AK: White Stone Press. ISBN 9781456485993.

- Solnit, Rebecca. River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West, 2003 ISBN 0-670-03176-3

- Yenne, Bill. Indian Wars: The Campaign for the American West, 2005. ISBN 1-59416-016-3.

Fiction

- Johnston, Terry C. Devil's Backbone: The Modoc War, 1872–3, New York: Macmillan, 1991

- Riddle, Paxton. Lost River, Berkley Trade Publications, 1999

External links

- Warren A. Beck and Ynez D. Hasse, "Indian Wars: The Modoc War", California State Military Museum, first published in their Historical Atlas of California, used with permission of the University of Oklahoma Press, 1975

- Gary Brecher, "The Modocs: A Beautiful Little War", The Exile, 23 February 2007

- The Beginning of the End, Documentary on the Modoc War produced by students from the Advanced Laboratory for Visual Anthropology at California State University, Chico.

- The Modoc War, Documentary produced by Oregon Public Broadcasting in cooperation with the Oregon Historical Society.