Louisiana Creole people

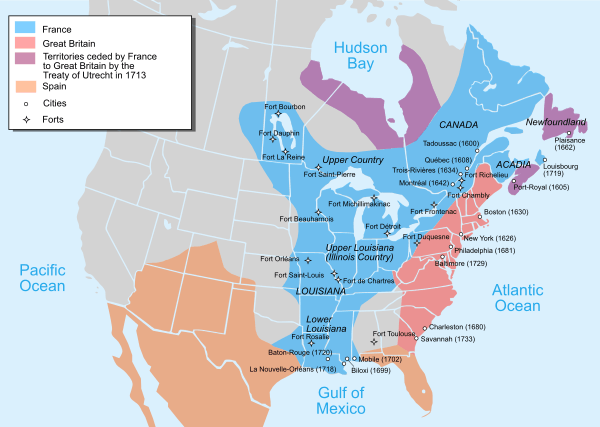

Louisiana Creole people (French: Créoles de la Louisiane, Spanish: Criollos de Luisiana) are persons descended from the inhabitants of colonial Louisiana during the period of both French and Spanish rule. Louisiana Creoles share cultural ties such as the traditional use of the French, Spanish, and Louisiana Creole languages[note 1] and predominant practice of Catholicism.[3]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Indeterminable | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Louisiana, Texas, Nevada, Alabama, Maryland, Florida, Georgia, Detroit, Chicago, New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco[1] | |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Spanish and Louisiana Creole (Kouri-Vini) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic, Protestant; some practice Voodoo | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Creoles of color

Peoples in Louisiana Spanish Americans Quebecois African Americans Canarian Americans Afro-Latino Native Americans Cajuns Métis Acadians Cuban Americans Isleño Portuguese Americans Dominican Americans Mexican Americans Stateside Puerto Ricans |

The term créole was originally used by French settlers to distinguish persons born in Louisiana from those born in the mother country or elsewhere. As in many other colonial societies around the world, creole was a term used to mean those who were "native-born", especially native-born Europeans such as the French and Spanish. It also came to be applied to African-descended slaves and Native Americans who were born in Louisiana.[3][4][5] The word is not a racial label, and people of fully European descent, fully African descent, or of any mixture therein (including Native American admixture) may identify as Creoles.

Starting with the native-born children of the French, as well as native-born African slaves, 'Creole' came to be used to describe Louisiana-born people to differentiate them from European immigrants and imported slaves. People of any race can and have identified as Creoles, and it is a misconception that créolité—the quality of being Creole—implies mixed racial origins. In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the class of free people of color in Louisiana became associated with the term Creole and further identification with mixed race took place during the interwar period in the 20th century. One historian has described this period as the "Americanization of Creoles," including an acceptance of the American binary racial system that divided Creoles into those who identified as mostly white and others as mostly black. (See Creoles of color.)

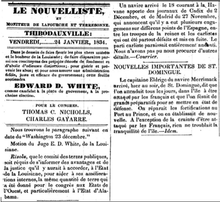

Créole was used casually as an identity in the 1700s in Louisiana. Starting in the very early 1800s in Louisiana, after the United States acquired this territory in the Louisiana Purchase, the term "Creole" began to take on a more political meaning and identity, especially for those persons of Latinate culture. These generally Catholic French speakers had a culture that contrasted with the Protestant English-speaking and Anglo culture of the new American settlers from the Upper South and the North.

In the early 19th century, amid the Haitian Revolution, thousands of refugees (both whites and free people of color from Saint-Domingue (affranchis or gens de couleur libres) arrived in New Orleans, often bringing enslaved Africans with them. So many refugees arrived that the city's population doubled. As more refugees were allowed in Louisiana, Haitian émigrés who had first gone to Cuba also arrived. These groups had strong influences on the city and its culture. Half of the white émigrė population of Haiti settled in Louisiana, especially in the greater New Orleans area. Later 19th-century immigrants to New Orleans, such as Irish, Germans and Italians, also married into the Creole groups. Most of the new immigrants were also Catholic.

There was also a sizable German Creole group of full German descent, centering on the parishes of St. Charles and St. John the Baptist. (It is for these settlers that the Côte des Allemands, literally "The German Coast", is named.) Over time, many of these groups assimilated, in part or completely, into the dominant French Creole culture, often adopting the French language and customs.

Although Cajuns are often presented in the twenty-first century as a group distinct from the Creoles, many historical accounts exist wherein persons with Acadian surnames either self-identify or are identified by others as being Creole, and some nineteenth century sources make specific references to "Acadian Creoles". As people born in colonial Louisiana, people of Acadian ancestry could and can be referred to as Creole, and until the early-mid twentieth century Cajuns were considered a subcategory of Louisiana Creole rather than a wholly separate group. Today, however, some Louisianans who identify as Cajun reject association as Creole, while others may embrace both identities.

Creoles of French descent, including those descended from the Acadians, have historically made up the majority of white Creoles in Louisiana. Louisiana Creoles are mostly Catholic in religion. Throughout the 19th century, most Creoles spoke French and were strongly connected to French colonial culture.[6] The sizeable Spanish Creole communities of Saint Bernard Parish and Galveztown spoke Spanish. The Malagueños of New Iberia spoke Spanish as well. The Isleños and Malagueños were Louisiana-born whites of Creole heritage. (Since the mid-20th century, however, the number of Spanish-speaking Creoles has declined in favor of English speakers, and few people under 80 years old speak Spanish.) They have maintained cultural traditions from the Canary Islands, where their immigrant ancestors came from.[2] However, just as with the Spanish Creoles, native languages of all Creole groups, whether French, Spanish or German, have declined over the years in favor of the English spoken by the majority of the population. The different varieties of Louisiana's Creoles shaped the state's culture, particularly in the southern areas around New Orleans and the plantation districts. Louisiana is known as the Creole State.[6]

While the sophisticated Creole society of New Orleans, which centered mainly on French Creoles, has historically received much attention, the Cane River area in northwest Louisiana, populated chiefly by Creoles of color, also developed its own strong Creole culture. Other enclaves of Creole culture have been located in south and southwest Louisiana: Frilot Cove, Bois Mallet, Grand Marais, Palmetto, Lawtell, Soileau and others. These communities have had a long history of cultural independence.

New Orleans also has had a significant historical population of Creoles of color as well, a group that was mostly free people of color, of mixed European, African, and Native American descent. Another area where many creoles can be found is within the River Parishes: St. Charles, St. John, and St. James. Many Creoles of German and French descent have also settled there. Most French Creoles are found in the greater New Orleans region, a seven parish-wide Creole cultural area including Orleans, St. Bernard, Jefferson, Plaquemines, St. Charles, St. Tammany and St. John the Baptist parishes. Also, Avoyelles and Evangeline parishes in Acadiana also have large French creole populations of French descent, also known as French Creoles.

History

1st French period

Through both the French and Spanish (late 18th century) regimes, parochial and colonial governments used the term Creole for ethnic French and Spanish born in the New World as opposed to Europe. Parisian French was the predominant language among colonists in early New Orleans.

Later the regional French evolved to contain local phrases and slang terms. The French Creoles spoke what became known as Colonial French. Because of isolation, the language in the colony developed differently from that in France. It was spoken by the ethnic French and Spanish and their Creole descendants.

The commonly accepted definition of Louisiana Creole today is a person descended from ancestors in Louisiana before the Louisiana Purchase by the United States in 1803.[3] An estimated 7,000 European immigrants settled in Louisiana during the 18th century, one percent of the number of British colonists in the Thirteen Colonies along the Atlantic coast. Louisiana attracted considerably fewer French colonists than did its West Indian colonies. After the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, which lasted more than two months, the colonists had numerous challenges ahead of them in the Louisiana frontier. Their living conditions were difficult: uprooted, they had to face a new, often hostile, environment, with difficult climate and tropical diseases. Many of these immigrants died during the maritime crossing or soon after their arrival.

Hurricanes, unknown in France, periodically struck the coast, destroying whole villages. The Mississippi Delta was plagued with periodic yellow fever epidemics. Europeans also brought the Eurasian diseases of malaria and cholera, which flourished along with mosquitoes and poor sanitation. These conditions slowed colonization. Moreover, French villages and forts were not always sufficient to protect from enemy offensives. Attacks by Native Americans represented a real threat to the groups of isolated colonists. The Natchez killed 250 colonists in Lower Louisiana in retaliation for encroachment by the Europeans. The Natchez warriors took Fort Rosalie (now Natchez, Mississippi) by surprise, killing many individuals. During the next two years, the French attacked the Natchez in return, causing them to flee or, when captured, be deported as slaves to their Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue (later Haiti).

Casket girls

Aside from French government representatives and soldiers, colonists included mostly young men who were recruited in French ports or in Paris. Some served as indentured servants; they were required to remain in Louisiana for a length of time, fixed by the contract of service, to pay back the cost of passage and board. During this time, they were "temporary semi-slaves". To increase the colonial population, the government recruited young Frenchwomen, known as filles à la cassette (in English, casket girls, referring to the casket or case of belongings they brought with them) to go to the colony to be wed to colonial soldiers. The king financed dowries for each girl. (This practice was similar to events in 17th-century Quebec: about 800 filles du roi (daughters of the king) were recruited to immigrate to New France under the monetary sponsorship of Louis XIV.)

In addition, French authorities deported some female criminals to the colony. For example, in 1721, the ship La Baleine brought close to 90 women of childbearing age from the prison of La Salpêtrière in Paris to Louisiana. Most of the women quickly found husbands among the male residents of the colony. These women, many of whom were most likely prostitutes or felons, were known as The Baleine Brides.[7] Such events inspired Manon Lescaut (1731), a novel written by the Abbé Prévost, which was later adapted as an opera in the 19th century.

Historian Joan Martin maintains that there is little documentation that casket girls (considered among the ancestors of French Creoles) were transported to Louisiana. (The Ursuline order of nuns, who were said to chaperone the girls until they married, have denied the casket girl myth as well.) Martin suggests this account was mythical. The system of plaçage that continued into the 19th century resulted in many young white men having women of color as partners and mothers of their children, often before or even after their marriages to white women.[8] French Louisiana also included communities of Swiss and German settlers; however, royal authorities did not refer to "Louisianans" but described the colonial population as "French" citizens.

Spanish period

The French colony was ceded to Spain in the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762), in the final stages of the Seven Years' War, which took place on two continents. The Spanish were slow and reluctant to fully occupy the colony, however, and did not do so until 1769. That year Spain abolished Indian slavery. In addition, Spanish liberal manumission policies contributed to the growth of the population of Creoles of Color, particularly in New Orleans. Nearly all of the surviving 18th-century architecture of the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) dates from the Spanish period (the Ursuline Convent an exception). These buildings were designed by French architects, as there were no Spanish architects in Louisiana. The buildings of the French Quarter are of a Mediterranean style also found in southern France.[9]

The mixed-race Creole descendants, who developed as a third class of Creoles of color (Gens de Couleur Libres), particularly in New Orleans, were strongly influenced by the French Catholic culture. By the end of the 18th century, many mixed-race Creoles had gained education and tended to work in artisan or skilled trades; a relatively high number were property and slave owners. The Louisiana Creole language developed primarily from the influence of French and African languages, enabling slaves from different tribes and colonists to communicate.

2nd French period and Louisiana Purchase

Spain ceded Louisiana back to France in 1800 through the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. Napoleon sold Louisiana (New France) to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, following defeat of his forces in Saint-Domingue. He had been trying to regain control of the island colony following a multi-year slave rebellion.

Thousands of refugees from the revolution, both whites and affranchis or Gens de Couleur Libres, arrived in New Orleans, often bringing their African slaves with them. These groups had a strong influence on the city, increasing the number of French speakers, Africans with strong traditional customs, and Creoles of Color. The Haitian Revolution ended in the slaves gaining independence in 1804, establishing the second republic in the Western Hemisphere and the first republic led by black people. While Governor Claiborne and other officials wanted to keep out additional free black men, the French Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking population. As more refugees were allowed in Louisiana, Haitian émigrés who had first gone to Cuba also arrived.[10] Many of the white Francophones had been deported by officials in Cuba in retaliation for Bonapartist schemes in Spain.[11] After the Purchase, many Americans were also migrating to Louisiana. Later European immigrants included Irish, Germans, and Italians.

During the antebellum years, the major commodity crops were sugar and cotton, cultivated on large plantations along the Mississippi River outside the city with slave labor. Plantations were developed in the French style, with narrow waterfronts for access on the river, and long plots running back inland.

Nearly 90 percent of early 19th century immigrants to the territory settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration from Cuba brought 2,731 whites; 3,102 Gens de Couleur Libres; and 3,226 enslaved persons of African descent, which in total doubled the city's population. The city became 63 percent black in population, a greater proportion than Charleston, South Carolina's 53 percent.[10]

The transfer of the French colony to the United States and the arrival of Anglo-Americans from New England and the South resulted in a cultural confrontation. Some Americans were reportedly shocked by aspects of the culture and French-speaking society of the newly acquired territory: the predominance of the French language and Roman Catholicism, the free class of mixed-race people, and the strong African traditions of enslaved peoples. They pressured the United States' first governor of the Louisiana Territory, W.C.C. Claiborne, to change it.

Particularly in the slave society of the South, slavery had become a racial caste. Since the late 17th century, children in the colonies took the status of their mothers at birth; therefore, all children of enslaved mothers were born into slavery, regardless of the race or status of their fathers. This produced many mixed-race slaves over the generations. Whites classified society into whites and blacks (the latter associated strongly with slaves). Although there was a growing population of free people of color, particularly in the Upper South, they generally did not have the same rights and freedoms as Creoles of Color in Louisiana under French and Spanish rule, who held office in some cases and served in the militia. For example, around 80 free Creoles of Color were recruited into the militia that fought in the Battle of Baton Rouge in 1779.[12] And 353 free Creoles of Color were recruited into the militia that fought in the Battle of New Orleans in 1812.[13] Later on, some of the descendants of these Creole of Color veterans of the Battle of New Orleans, like Caesar Antoine, went on to fight in the American Civil War.

When Claiborne made English the official language of the territory, the French Creoles of New Orleans were outraged, and reportedly paraded in protest in the streets. They rejected the Americans' effort to transform them overnight. In addition, upper-class French Creoles thought that many of the arriving Americans were uncouth, especially the rough Kentucky boatmen (Kaintucks) who regularly visited the city, having maneuvered flatboats down the Mississippi River filled with goods for market.

Realizing that he needed local support, Claiborne restored French as an official language. In all forms of government, public forums, and in the Catholic Church, French continued to be used. Most importantly, Louisiana French and Louisiana Creole remained the languages of the majority of the population of the state, leaving English and Spanish as minority languages.

Ethnic blend and race

Colonists referred to themselves and enslaved Black people who were native-born as creole, to distinguish them from new arrivals from France and Spain as well as Africa.[3] Native Americans, such as the Creek people, intermixed with Creoles also, making three races present in the ethnic group.

Like "Cajun," the term "Creole" is a popular name used to describe cultures in the southern Louisiana area. "Creole" can be roughly defined as "native to a region," but its precise meaning varies according to the geographic area in which it is used. Generally, however, Creoles felt the need to distinguish themselves from the influx of American and European immigrants coming into the area after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. "Creole" is still used to describe the heritage and customs of the various people who settled Louisiana during the early French colonial times. In addition to the French Canadians, the amalgamated Creole culture in southern Louisiana includes influences from the Chitimacha, Houma and other native tribes, enslaved West Africans, Spanish-speaking Isleños (Canary Islanders) and French-speaking Gens de Couleur Libres from the Caribbean.[14]

As a group, mixed-race Creoles rapidly began to acquire education, skills (many in New Orleans worked as craftsmen and artisans), businesses and property. They were overwhelmingly Catholic, spoke Colonial French (although some also spoke Louisiana Creole), and kept up many French social customs, modified by other parts of their ancestry and Louisiana culture. The Creoles of Color often married among themselves to maintain their class and social culture. The French-speaking mixed-race population came to be called "Creoles of color". It was said that "New Orleans persons of color were far wealthier, more secure and more established than freed unmixed Black Creoles and Cajuns elsewhere in Louisiana."[5]

Under the French and Spanish rulers, Louisiana developed a three-tiered society, similar to that of Haiti, Cuba, Brazil, Saint Lucia, Martinique, Guadeloupe and other Latin colonies. This three-tiered society included white Creoles; a prosperous, educated group of mixed-race Creoles of European, African and Native American descent; and the far larger class of African and Black Creole slaves. The status of mixed-race Creoles of color (Gens de Couleur Libres) was one they guarded carefully. By law they enjoyed most of the same rights and privileges as white Creoles. They could and often did challenge the law in court and won cases against white Creoles. They were property owners and created schools for their children. In many cases though, these different tiers viewed themselves as one group, as other Iberoamerican and Francophone ethnic groups commonly did. Race did not play as central a role as it does in Anglo-American culture: oftentimes, race was not a concern, but instead, family standing and wealth were key distinguishing factors in New Orleans and beyond.[3] The Creole civil rights activist Rodolphe Desdunes explained the difference between Creoles and Anglo-Americans, concerning the widespread belief in racialism by the latter, as follows:

The groups (Latin and Anglo New Orleaneans) had "two different schools of politics [and differed] radically ... in aspiration and method. One hopes [Latins], and the other doubts [Anglos]. Thus we often perceive that one makes every effort to acquire merits, the other to gain advantages. One aspires to equality, the other to identity. One will forget that he is a Negro to think that he is a man; the other will forget that he is a man to think that he is a Negro.[15]

After the United States acquired the area in the Louisiana Purchase, mixed-race Creoles of Color resisted American attempts to impose their binary racial culture. In the American South slavery had become virtually a racial caste, in which most people of any African descent were considered to be lower in status. The planter society viewed it as a binary culture, with whites and blacks (the latter including everyone other than whites, although for some years they counted mulattos separately on censuses).[3]

While the American Civil War promised rights and opportunities for the enslaved, the Creoles of Color, who had long been free before the war, worried about losing their identity and position. The Americans did not legally recognize a three-tiered society; nevertheless, some Creoles of Color such as Thomy Lafon, Victor Séjour and others, used their position to support the abolitionist cause.[16] And the Creole of Color, Francis E. Dumas, emancipated all of his slaves and organized them into a company in the Second Regiment of the Louisiana Native Guards.[17]

Following the Union victory in the Civil War, the Louisiana three-tiered society was gradually overrun by more Anglo-Americans, who classified everyone by the South's binary division of "black" and "white". During the Reconstruction era, Democrats regained power in the Louisiana state legislature by using paramilitary groups like the White League to suppress black voting. The Democrats enforced white supremacy by passing Jim Crow laws and a constitution near the turn of the 20th century that effectively disenfranchised most blacks and Creoles of color through discriminatory application of voter registration and electoral laws. Some white Creoles, such as the ex-Confederate general Pierre G. T. Beauregard, advocated against racism, and became proponents of Black Civil Rights and Black suffrage, involving themselves in the creation of the Louisiana Unification Movement that called for equal rights for blacks, denounced discrimination and the abandonment of segregation.[18][19]

The US Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 supported the binary society and the policy of "separate but equal" facilities (which were seldom achieved in fact) in the segregated South.[3] Some white Creoles, heavily influenced by white American society, increasingly claimed that the term Creole applied to whites only. According to Virginia R. Domínguez:

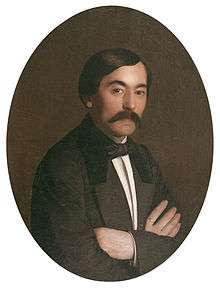

Charles Gayarré ... and Alcée Fortier ... led the outspoken though desperate defense of the Creole. As bright as these men clearly were, they still became engulfed in the reclassification process intent on salvaging white Creole status. Their speeches consequently read more like sympathetic eulogies than historical analysis.[20]

.jpg)

Sybil Kein suggests that, because of the white Creoles struggle for redefinition, they were particularly hostile to the exploration by the writer George Washington Cable of the multi-racial Creole society in his stories and novels. She believes that in The Grandissimes, he exposed white Creoles' preoccupation with covering up blood connections with Creoles of Color. She writes:

There was a veritable explosion of defenses of Creole ancestry. The more novelist George Washington Cable engaged his characters in family feuds over inheritance, embroiled them in sexual unions with blacks and mulattoes and made them seem particularly defensive about their presumably pure Caucasian ancestry, the more vociferously the white Creoles responded, insisting on purity of white ancestry as a requirement for identification as Creole.[20]

In the 1930s, populist Governor Huey Long satirized such Creole claims, saying that you could feed all the "pure white" people in New Orleans with a cup of beans and a half a cup of rice, and still have food left over![21] The effort to impose Anglo-American binary racial classification on Creoles continued, however. In 1938, in Sunseri v. Cassagne—the Louisiana Supreme Court proclaimed traceability of African ancestry to be the only requirement for definition of colored. And during her time as Registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics for the City of New Orleans (1949–1965), Naomi Drake tried to impose these binary racial classifications. She unilaterally changed records to classify mixed-race individuals as black if she found they had any black (or African) ancestry, an application of hypodescent rules, and did not notify people of her actions.[22]

Among the practices Drake directed was having her workers check obituaries. They were to assess whether the obituary of a person identified as white provided clues that might help show the individual was "really" black, such as having black relatives, services at a traditionally black funeral home, or burial at a traditionally black cemetery—evidence which she would use to ensure the death certificate classified the person as black.[23]

Not everyone accepted Drake's actions and people filed thousands of cases against the office to have racial classifications changed and to protest her withholding legal documents of vital records. This caused much embarrassment and disruption, finally causing the city to fire her in 1965.[24]

Culture

Cuisine

Louisiana Creole cuisine is recognized as a unique style of cooking originating in New Orleans, starting in the early 1700s. It makes use of what is sometimes called the Holy trinity: onions, celery and green peppers. It has developed primarily from various European, African, and Native American historic culinary influences. A distinctly different style of Creole or Cajun cooking exists in Acadiana.

Gumbo (Gombô in Louisiana Creole, Gombo in Louisiana French) is a traditional Creole dish from New Orleans with French, Spanish, Native American, African, German, Italian, and Caribbean influences. It is a roux-based meat stew or soup, sometimes made with some combination of any of the following: seafood (usually shrimp, crabs, with oysters optional, or occasionally crawfish), sausage, chicken (hen or rooster), alligator, turtle, rabbit, duck, deer or wild boar. Gumbo is often seasoned with filé, which is dried and ground sassafras leaves. Both meat and seafood versions also include the "Holy Trinity" and are served like stew over rice. It developed from French colonists trying to make bouillabaisse with New World ingredients. Starting with aromatic seasonings, the French used onions and celery as in a traditional mirepoix, but lacked carrots, so they substituted green bell peppers. Africans contributed okra, traditionally grown in regions of Africa, the Middle East and Spain. Gombo is the Louisiana French word for okra, which is derived from a shortened version of the Bantu words kilogombó or kigambó, also guingambó or quinbombó. "Gumbo" became the anglicized version of the word 'Gombo' after the English language became dominant in Louisiana. In Louisiana French dialects, the word "gombo" still refers to both the hybrid stew and the vegetable. The Choctaw contributed filé; the Spanish contributed peppers and tomatoes; and new spices were adopted from Caribbean dishes. The French later favored a roux for thickening. In the 19th century, the Italians added garlic. After arriving in numbers, German immigrants dominated New Orleans city bakeries, including those making traditional French bread. They introduced having buttered French bread as a side to eating gumbo, as well as a side of German-style potato salad.

Jambalaya is the second of the famous Louisiana Creole dishes. It developed in the European communities of New Orleans. It combined ham with sausage, rice and tomato as a variation of the Spanish dish paella, and was based on locally available ingredients. The name for jambalaya comes from the Occitan language spoken in southern France, where it means "mash-up." The term also refers to a type of rice cooked with chicken.

Today, jambalaya is commonly made with seafood (usually shrimp) or chicken, or a combination of shrimp and chicken. Most versions contain smoked sausage, more commonly used instead of ham in modern versions. However, a version of jambalaya that uses ham with shrimp may be closer to the original Creole dish.[25]

Jambalaya is prepared in two ways: "red" and "brown". Red is the tomato-based version native to New Orleans; it is also found in parts of Iberia and St. Martin parishes, and generally uses shrimp or chicken stock. The red-style Creole jambalaya is the original version. The "brown" version is associated with Cajun cooking and does not include tomatoes.

Red beans and rice is a dish of Louisiana and Caribbean influence, originating in New Orleans. It contains red beans, the "holy trinity" of onion, celery, and bell pepper, and often andouille smoked sausage, pickled pork, or smoked ham hocks. The beans are served over white rice. It is one of the famous dishes in Louisiana, and is associated with "washday Monday". It could be cooked all day over a low flame while the women of the house attended to washing the family's clothes.

Music

Zydeco (a transliteration in English of 'zaricô' (snapbeans) from the song, "Les haricots sont pas salés"), was born in black Creole communities on the prairies of southwest Louisiana in the 1920s. It is often considered the Creole music of Louisiana. Zydeco, a derivative of Cajun music, purportedly hails from Là-là, a genre of music now defunct, and old south Louisiana jurés. As Louisiana French and Louisiana Creole was the lingua franca of the prairies of southwest Louisiana, zydeco was initially sung only in Louisiana French or Creole. Later, Louisiana Creoles, such as the 20th-century Chénier brothers, Andrus Espree (Beau Jocque), Rosie Lédet and others began incorporating a more bluesy sound and added a new linguistic element to zydeco music: English. Today, zydeco musicians sing in English, Louisiana Creole or Colonial Louisiana French.

Today's Zydeco often incorporates a blend of swamp pop, blues, and/or jazz as well as "Cajun Music" (originally called Old Louisiana French Music). An instrument unique to zydeco is a form of washboard called the frottoir or scrub board. This is a vest made of corrugated aluminum, and played by the musician working bottle openers, bottle caps or spoons up and down the length of the vest. Another instrument used in both Zydeco and Cajun music since the 1800s is the accordion. Zydeco music makes use of the piano or button accordion while Cajun music is played on the diatonic accordion, or Cajun accordion, often called a "squeeze box". Cajun musicians also use the fiddle and steel guitar more often than do those playing Zydeco.

Zydeco can be traced to the music of enslaved African people from the 19th century. It is represented in Slave Songs of the United States, first published in 1867. The final seven songs in that work are printed with melody along with text in Louisiana Creole. These and many other songs were sung by slaves on plantations, especially in St. Charles Parish, and when they gathered on Sundays at Congo Square in New Orleans.

Among the Spanish Creole people highlights, between their varied traditional folklore, the Canarian Décimas, romances, ballads and pan-Hispanic songs date back many years, even to the Medieval Age. This folklore was carried by their ancestors from the Canary Islands to Louisiana in the 18th century. It also highlights their adaptation to the Isleño music to other music outside of the community (especially from the Mexican Corridos).[2]

Language

Louisiana Creole (Kréyol La Lwizyàn) is a French Creole[26] language spoken by the Louisiana Creole people and sometimes Cajuns and Anglo-residents of the state of Louisiana. The language consists of elements of French, Spanish, African and Native American roots.

Louisiana French (LF) is the regional variety of the French language spoken throughout contemporary Louisiana by individuals who today identify ethno-racially as Creole, Cajun or French, as well as some who identify as Spanish (particularly in New Iberia and Baton Rouge, where the Creole people are a mix of French and Spanish and speak the French language[2]), African-American, white, Irish, or of other origins. Individuals and groups of individuals through innovation, adaptation, and contact continually enrich the French language spoken in Louisiana, seasoning it with linguistic features that can sometimes only be found in Louisiana.[27][28][29][30][31]

Tulane University's Department of French and Italian website prominently declares "In Louisiana, French is not a foreign language".[32] Figures from U.S. decennial censuses report that roughly 250,000 Louisianans claimed to use or speak French in their homes.[33]

Among the 18 governors of Louisiana between 1803 and 1865, six were French Creoles and spoke French: Jacques Villeré, Pierre Derbigny, Armand Beauvais, Jacques Dupré, Andre B. Roman and Alexandre Mouton.

According to the historian Paul Lachance, "the addition of white immigrants to the white creole population enabled French-speakers to remain a majority of the white population [in New Orleans] until almost 1830. If a substantial proportion of Creoles of Color and slaves had not also spoken French, however, the Gallic community would have become a minority of the total population as early as 1820."[34] In the 1850s, white Francophones remained an intact and vibrant community; they maintained instruction in French in two of the city's four school districts.[35] In 1862, the Union general Ben Butler abolished French instruction in New Orleans schools, and statewide measures in 1864 and 1868 further cemented the policy.[35] By the end of the 19th century, French usage in the city had faded significantly.[36] However, as late as 1902 "one-fourth of the population of the city spoke French in ordinary daily intercourse, while another two-fourths was able to understand the language perfectly,"[37] and as late as 1945, one still encountered elderly Creole women who spoke no English.[38] The last major French-language newspaper in New Orleans, L'Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans, ceased publication on December 27, 1923, after ninety-six years;[39] according to some sources Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans continued until 1955.[40]

Today, it is generally in more rural areas that people continue to speak Louisiana French or Louisiana Creole. Also during the '40s and '50s many Creoles left Louisiana to find work in Texas, mostly in Houston and East Texas. The language and music is widely spoken there; the 5th ward of Houston was originally called Frenchtown due to that reason. There were also Zydeco clubs started in Houston, like the famed Silver Slipper owned by a Creole named Alfred Cormier that has hosted the likes of Clifton Chenier and Boozoo Chavais.

On the other hand, Spanish usage has fallen markedly over the years among the Spanish Creoles. Still, in the first half of twentieth century, most of the people of Saint Bernard and Galveztown spoke the Spanish language with the Canarian Spanish dialect (the ancestors of these Creoles were from the Canary Islands) of the 18th century, but the government of Louisiana imposed the use of English in these communities, especially in the schools (e.g. Saint Bernard) where if a teacher heard children speaking Spanish she would fine them and punish them. Now, only some people over the age of 80 can speak Spanish in these communities. Most of the youth of Saint Bernard can only speak English.[2]

New Orleans Mardi Gras

Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday in English) in New Orleans, Louisiana, is a Carnival celebration well known throughout the world. It has colonial French roots.

The New Orleans Carnival season, with roots in preparing for the start of the Christian season of Lent, starts after Twelfth Night, on Epiphany (January 6). It is a season of parades, balls (some of them masquerade balls) and king cake parties. It has traditionally been part of the winter social season; at one time "coming out" parties for young women at débutante balls were timed for this season.

Celebrations are concentrated for about two weeks before and through Fat Tuesday (Mardi Gras in French), the day before Ash Wednesday. Usually there is one major parade each day (weather permitting); many days have several large parades. The largest and most elaborate parades take place the last five days of the season. In the final week of Carnival, many events large and small occur throughout New Orleans and surrounding communities.

The parades in New Orleans are organized by Carnival krewes. Krewe float riders toss throws to the crowds; the most common throws are strings of plastic colorful beads, doubloons (aluminum or wooden dollar-sized coins usually impressed with a krewe logo), decorated plastic throw cups, and small inexpensive toys. Major krewes follow the same parade schedule and route each year.

While many tourists center their Mardi Gras season activities on Bourbon Street and the French Quarter, none of the major Mardi Gras parades has entered the Quarter since 1972 because of its narrow streets and overhead obstructions. Instead, major parades originate in the Uptown and Mid-City districts and follow a route along St. Charles Avenue and Canal Street, on the upriver side of the French Quarter.

To New Orleanians, "Mardi Gras" specifically refers to the Tuesday before Lent, the highlight of the season. The term can also be used less specifically for the whole Carnival season, sometimes as "the Mardi Gras season". The terms "Fat Tuesday" or "Mardi Gras Day" always refer only to that specific day.

Creole places

Cane River Creoles

While the sophisticated Creole society of New Orleans has historically received much attention, the Cane River area developed its own strong Creole culture. The Cane River Creole community in the northern part of the state, along the Red River and Cane River, is made up of multi-racial descendants of French, Spanish, Africans, Native Americans, similar mixed Creole migrants from New Orleans and various other ethnic groups who inhabited this region in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The community is located in and around Isle Brevelle in lower Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana. There are many Creole communities within Natchitoches Parish, including Natchitoches, Cloutierville, Derry, Gorum and Natchez. Many of their historic plantations still exist.[41] Some have been designated as National Historic Landmarks, and are noted within the Cane River National Heritage Area, as well as the Cane River Creole National Historical Park. Some plantations are sites on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail.

Isle Brevelle, the area of land between Cane River and Bayou Brevelle, encompasses approximately 18,000 acres (73 km2) of land, 16,000 acres of which are still owned by descendants of the original Creole families. The Cane River as well as Avoyelles and St. Landry Creole family surnames include but are not limited to: Antee, Anty, Arceneaux, Arnaud, Balthazar, Barre', Bayonne, Beaudoin, Bellow, Bernard, Biagas, Bossier, Boyér, Brossette, Buard, Byone, Carriere, Cassine, Catalon, Chevalier, Christophe, Cloutier, Colson, Colston, Conde, Conant, Coutée, Cyriak, Cyriaque, Damas, DeBòis, DeCuir, Deculus, Delphin, De Sadier, De Soto, Dubreil, Dunn, Dupré. Esprit, Fredieu, Fuselier, Gallien, Goudeau, Gravés, Guillory, Hebert, Honoré, Hughes, LaCaze, LaCour, Lambre', Landry, Laurent, LéBon, Lefìls, Lemelle, LeRoux, Le Vasseur, Llorens, Mathés, Mathis, Métoyer, Mezière, Monette, Moran, Mullone, Pantallion, Papillion, Porche, PrudHomme, Rachal, Ray, Reynaud, Roque, Sarpy, Sers, Severin, Simien, St. Romain, St. Ville, Sylvie, Sylvan, Tyler, Vachon, Vallot, Vercher and Versher. (Most of the surnames are of French and sometimes Spanish origin).[41]

Pointe Coupee Creoles

Another historic area to Louisiana is Pointe Coupee, an area northwest of Baton Rouge. This area is known for the False River; the parish seat is New Roads, and villages including Morganza are located off the river. This parish is known to be uniquely Creole; today a large portion of the nearly 22,000 residents can trace Creole ancestry. The area was noted for its many plantations and cultural life during the French, Spanish, and American colonial periods.

The population here had become bilingual or even trilingual with French, Louisiana Creole, and English because of its plantation business before most of Louisiana. The Louisiana Creole language is widely associated with this parish; the local mainland French and Creole (i.e., locally born) plantation owners and their African slaves formed it as communication language, which became the primary language for many Pointe Coupee residents well into the 20th century. The local white and black populations as well as persons of blended ethnicity spoke the language, because of its importance to the region; Italian immigrants in the 19th century often adopted the language.[42]

Common Creole family names of the region include the following: Aguillard, Amant, Bergeron, Bonaventure, Boudreaux, Carmouche, Chenevert, Christophe, Decuir, Domingue, Duperon, Eloi, Elloie, Ellois, Fabre, Francois, Gaines, Gremillion, Guerin, Honoré, Jarreau, Joseph, Morel, Olinde, Porche, Pourciau, St. Patin, Ricard, St. Romain, Tounoir, Valéry and dozens more.[43]

Brian J. Costello, an 11th generation Pointe Coupee Parish Creole, is the premiere historian, author and archivist on Pointe Coupee's Creole population, language, social and material culture. Most of his 19 solely-authored books, six co-authored books and numerous feature articles and participation in documentaries since 1987 have addressed these topics. He was immersed in the area's Louisiana Creole dialect in his childhood, through inter-familial and community immersion and is, therefore, one of the dialect's most fluent, and last, speakers.

Avoyelles Creoles

Avoyelles Parish has a history rich in Creole ancestry. Marksville has a significant populace of French Creoles who have Native American ancestry. The languages that are spoken are Louisiana French and English. This parish was established in 1750. The Creole community in Avoyelles parish is alive and well and has a unique blend of family, food and Creole culture. Creole family names of this region are: Auzenne, Barbin, Beaudoin, Biagas, Bordelon, Boutte, Broussard, Carriere, Chargois, DeBellevue, DeCuir, Deshotels, Dufour, DuCote, Esprit, Fontenot, Fuselier, Gaspard, Gauthier, Goudeau, Gremillion, Guillory, Lamartiniere, Lemelle, Lemoine, LeRoux, Mayeux, Mouton, Moten, Muellon, Normand, Perrie, Rabalais, Ravarre, Saucier, Sylvan and Tyler.[44] A French Creole Heritage day has been held annually in Avoyelles Parish on Bastille Day since 2012.

Evangeline Parish Creoles

Evangeline Parish was formed out of the northwestern part of St. Landry Parish in 1910, and is therefore, a former part of the old Poste des Opelousas territory. Most of this region's population was a direct result of the North American Creole & Métis influx of 1763, the result of the end of the French & Indian War which saw former French colonial settlements from as far away as "Upper Louisiana" (Great Lakes region, Indiana, Illinois) to "Lower Louisiana's" (Illinois, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama), ceded to British America. The majority of these French Creoles and Métis peoples chose to leave their former homes electing to head for the only 'French' exempted settlement area in Lower Louisiana, the "Territory of Orleans" or the modern State of Louisiana.

These Creoles and Métis families generally did not remain in New Orleans and opted for settlement in the northwestern "Creole parishes" of higher ground. This area reaches upwards to Pointe Coupee, St. Landry, Avoyelles and what became Evangeline Parish in 1910. Along with these diverse Métis & Creole families came West Indian slaves (Caribbean people).

Still later, Saint-Domingue/Haitian Creoles, Napoleonic soldiers, and 19th century French families would also settle this region. One of Napoleon Bonaparte's adjutant majors is actually considered the founder of Ville Platte, the parish seat of Evangeline Parish. General Antoine Paul Joseph Louis Garrigues de Flaugeac and his fellow Napoleonic soldiers, Benoit DeBaillon, Louis Van Hille, and Wartelle's descendants also settled in St. Landry Parish and became important public, civic, and political figures. They were discovered on the levee in tattered uniforms by a wealthy Creole planter, "Grand Louis' Fontenot of St. Landry (and what is now, Evangeline Parish), a descendant of one of Governor Jean-Batiste LeMoyne, Sieur de Bienville's French officers from Fort Toulouse, in what is now the State of Alabama.[45]

Many Colonial French, Swiss German, Austrian, and Spanish Creole surnames still remain among prominent and common families alike in Evangeline Parish. Some later Irish and Italian names also appear. Surnames such as, Ardoin, Aguillard, Mouton, Bordelon, Boucher, Brignac, Brunet, Buller (Buhler), Catoire, Chapman, Coreil, Darbonne, DeBaillion, DeVille, DeVilliers, Duos, Dupre' Estillette, Fontenot, Guillory, Gradney, LaFleur, Landreneau, LaTour, LeBas, LeBleu, LeRoux, Milano-Hebert, Miller, Morein, Moreau, Moten, Mounier, Ortego, Perrodin, Pierotti, Pitre (rare Acadian-Creole), Rozas, Saucier, Schexnayder, Sebastien, Sittig, Soileau, Vidrine, Vizinat and many more are reminiscent of the late French Colonial, early Spanish and later American period of this region's history.[46]

As of 2013, the parish was once again recognized by the March 2013 Regular Session of the Louisiana Legislature as part of the Creole Parishes, with the passage of SR No. 30. Other parishes so recognized include Avoyelles, St. Landry and Pointe Coupee Parishes. Natchitoches Parish also remains recognized as "Creole".

Evangeline Parish's French-speaking Senator, Eric LaFleur sponsored SR No. 30 which was written by Louisiana French Creole scholar, educator and author, John laFleur II. The parish's namesake of "Evangeline" is a reflection of the affection the parish's founder, Paulin Fontenot had for Henry Wadsworth's famous poem of the same name, and not an indication of the parish's ethnic origin. The adoption of "Cajun" by the residents of this parish reflects both the popular commerce as well as media conditioning, since this northwestern region of the French-speaking triangle was never part of the Acadian settlement region of the Spanish period.[47]

The community now hosts an annual "Creole Families Bastille Day (weekend) Heritage & Honorarium Festival in which a celebration of Louisiana's multi-ethnic French Creoles is held, with Catholic mass, Bastille Day Champagne toasting of honorees who've worked in some way to preserve and promote the French Creole heritage and language traditions. Louisiana authors, Creole food, and cultural events featuring scholarly lectures and historical information along with fun for families with free admission, and vendor booths are also a feature of this very interesting festival which unites all French Creoles who share this common culture and heritage.

St. Landry Creoles

St. Landry Parish has a significant population of Creoles, especially in Opelousas and its surrounding areas. The traditions and Creole heritage are prevalent in Opelousas, Port Barre, Melville, Palmetto, Lawtell, Eunice, Swords, Mallet, Frilot Cove, Plaisance, Pitreville, and many other villages, towns and communities. The Roman Catholic Church and French/Creole language are dominant features of this rich culture. Zydeco musicians host festivals all through the year.

Notable people

See also

- Creoles of color

- Cane River Creole National Historical Park

- Melrose Plantation

- French Quarter

- Faubourg Marigny

- Tremé

- Little New Orleans

- Frenchtown, Houston

- Magnolia Springs, Alabama

- Institute Catholique

- 7th Ward of New Orleans

- Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

- Native Americans in the United States

- Isleños

- Spanish Americans

- French Americans

- Canarian Americans

- Mexicans

Notes

- As of 2007 According to anthropologist Samuel G. Armistead, even in New Iberia and Baton Rouge, where the Creole people are a mix of French and Spanish, they primarily speak French as a second language and their names and surnames are French-descended. In Saint Bernard Parish and Galveztown, some people are descendants of colonial Spanish settlers and a few elders still speak Spanish.[2]

Further reading

- Brasseaux, Carl A. Acadian to Cajun: Transformation of a people, 1803–1877 (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1992)

- Eaton, Clement. The Growth of Southern Civilization, 1790–1860 (1961) pp 125–49, broad survey

- Eble, Connie. "Creole in Louisiana." South Atlantic Review (2008): 39–53. in JSTOR

- Gelpi Jr, Paul D. "Mr. Jefferson's Creoles: The Battalion d'Orléans and the Americanization of Creole Louisiana, 1803–1815." Louisiana History (2007): 295–316. in JSTOR

- Landry, Rodrigue, Réal Allard, and Jacques Henry. "French in South Louisiana: towards language loss." Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development (1996) 17#6 pp: 442–468.

- Stivale, Charles J. Disenchanting les bons temps: identity and authenticity in Cajun music and dance (Duke University Press, 2002)

- Tregle, Joseph G. "Early New Orleans Society: A Reappraisal." Journal of Southern History (1952) 18#1 pp: 20–36. in JSTOR

- Douglas, Nick (2013). Finding Octave: The Untold Story of Two Creole Families and Slavery in Louisiana. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Jacques Anderson, Beverly (2011). Cherished Memories: Snapshots of Life and Lessons from a 1950s New Orleans Creole Village. iUniverse.com.

- Malveaux, Vivian (2009). Living Creole and Speaking It Fluently. AuthorHouse.

- Kein, Sybil (2009). Creole: the history and legacy of Louisiana's free people of color. Louisiana State University Press.

- Jolivette, Andrew (2007). Louisiana Creoles: Cultural Recovery and Mixed-Race Native American Identity. Lexington Books.

- Gehman, Mary (2009). The Free People of Color of New Orleans: An Introduction. Margaret Media, Inc.

- Clark, Emily (2013). The Strange History of the American Quadroon: Free Women of Color in the Revolutionary Atlantic World. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Dominguez, Virginia (1986). White by Definition: Social Classification in Creole Louisiana. Rutgers University Press.

- Hirsch, Arnold R. (1992). Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization. Louisiana State University Press.

- Wilson, Warren Barrios (2009). Dark, Light, Almost White, Memoir of a Creole Son. Barrios Trust.

- laFleur II, John, Costello, Brian, Fandrich, Dr Ina (2013). Louisiana's French Creole Culinary & Linguistic Traditions: Facts vs Fiction Before and Since Cajunization. BookRix GmbH & Co. KG.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Thompson, Shirley Elizabeth (2009). Exiles at Home: The Struggle to Become American in Creole New Orleans. Harvard University Press.

- Martin, Munro, Britton, Celia (2012). American Creoles: The Francophone Caribbean and the American South. Liverpool University Press.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

-

- smaller populations in Cuba, Haiti and Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Mexico,

- G. Armistead, Samuel. La Tradición Hispano – Canaria en Luisiana (in Spanish: Hispanic Tradition – Canary in Louisiana). Page 26 (prorogue of the Spanish edition) and pages 51 – 61 (History and languages). Anrart Ediciones. Ed: First Edition, March 2007.

- Kathe Managan, The Term "Creole" in Louisiana : An Introduction Archived December 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, lameca.org. Retrieved December 5, 2013

- Bernard, Shane K, "Creoles" Archived June 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, "KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana". Retrieved October 19, 2011

- Helen Bush Caver and Mary T. Williams, "Creoles", Multicultural America, Countries and Their Cultures Website. Retrieved February 3, 2009

- Christophe Landry, "Primer on Francophone Louisiana: more than Cajun", "francolouisiane.com". Retrieved October 19, 2011

- National Genealogical Society Quarterly, December 1987; vol.75, number 4: "The Baleine Brides: A Missing Ship's Roll for Louisiana"

- Joan M. Martin, Plaçage and the Louisiana Gens de Couleur Libre, in Creole, edited by Sybil Kein, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 2000.

- "National Park Service. Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. Ursuline Convent". Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "Haitian Immigration: 18th & 19th Centuries", In Motion: African American Migration Experience, New York Public Library. Retrieved May 7, 2008

- The Bourgeois Frontier : French Towns, French Traders and American Expansion, by Jay Gitlin (2009). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10118-8, pg 54

- Charles Gayarré, History of Louisiana: The Spanish domination, William J. Widdleton, 1867, pp 126–132

- "The Battle of New Orleans", wcny.org. Retrieved September 1, 2016

- "Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve: Places Reflecting America's Diverse Cultures Explore their Stories in the National Park System: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary". National Park Service. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- Christophe Landry, "Wearing the wrong spectacles and catching the Time disease!" Archived 2016-10-14 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 23, 2016

- "Keep Up The Fight", theneworleanstribune.com. Retrieved September 1, 2016

- Thompson, Shirley Elizabeth (2009). Exiles at Home: The Struggle to Become American in Creole New Orleans. Harvard University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-674-02351-2.

- Williams, pp. 282–84.

- name="Monumental Heist: A Story of Race; A Race to the White House"Charles E. Marsala (2018). "24". Monumental Heist: A Story of Race; A Race to the White House. eBookIt.com.

- Kein, Sybil (2009). Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana's Free People of Color. Louisiana State University Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780807142431.

- Delehanty, Randolph (1995). New Orleans: Elegance and Decadence. Chronicle Books. p. 14.

- Dominguez, Virginia (1986). White by Definition: Social Classification in Creole Louisiana. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. pp. 36–45. ISBN 0-8135-1109-7.

- O'Byrne, James (August 16, 1993). "Many feared Naomi Drake and powerful racial whim". The Times-Picayune. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- Baca, George; Khan, Aisha; Palmié, Stephan, eds. (2009). Empirical Futures: Anthropologists and Historians Engage the Work of Sidney W. Mintz. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-8078-5988-9.

- Jambalaya." Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, John F. Mariani, Bloomsbury, 2nd edition, 2014. Credo Reference, https://login.avoserv2.library.fordham.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/bloomfood/jambalaya/0?institutionId=3205. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- "Louisiana Creole Dictionary", www.LouisianaCreoleDictionary.com Website. Retrieved July 15, 2014

- Brasseaux, Carl A. (2005). French, Cajun, Creole, Houma: A Primer on Francophone Louisiana. Baton Rouge: LSU Press. ISBN 0-8071-3036-2.

- Klingler, Thomas A.; Picone, Michael; Valdman, Albert (1997). "The Lexicon of Louisiana French". In Valdman, Albert (ed.). French and Creole in Louisiana. Springer. pp. 145–170. ISBN 0-306-45464-5.

- Landry, Christophe (2010). "Francophone Louisiana: more than Cajun". Louisiana Cultural Vistas. 21 (2): 50–55.

- Fortier, Alcée (1894). Louisiana Studies: Literature, Customs and Dialects, History and Education. New Orleans: Tulane University.

- Klingler, Thomas A. (2003). Sanchez, T.; Horesh, U. (eds.). "Language labels and language use among Cajuns and Creoles in Louisiana". U Penn Working Papers in Linguistics. 9 (2): 77–90.

- "Tulane University – School of Liberal Arts – HOME". Tulane.edu. April 16, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- "Table 4. Languages Spoken at Home by Persons 5 Years and Over, by State: 1990 Census". Census.gov. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- Quoted in Jay Gitlin, The Bourgeois Frontier: French Towns, French Traders, and American Expansion, Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10118-8 p. 159

- Gitlin, The Bourgeois Frontier, p. 166

- Gitlin, The Bourgeois Frontier, p. 180

- Leslie's Weekly, December 11, 1902

- Gumbo Ya-Ya: Folk Tales of Louisiana by Robert Tallant & Lyle Saxon. Louisiana Library Commission: 1945, p. 178

- French, Cajun, Creole, Houma: A Primer on Francophone Louisiana by Carl A. Brasseaux Louisiana State University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8071-3036-2 pg 32

- New Orleans City Guide. The Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration: 1938 pg 90

- "Cane River Creole Community-A Driving Tour" Archived March 31, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Louisiana Regional Folklife Center, Northwestern State University. Retrieved February 3, 2009

- Costello, Brian J. C'est Ca Ye' Dit. New Roads Printing, 2004

- Costello, Brian J. A History of Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana. Margaret Media, 2010.

- "Avoyelles Family Name Origins". avoyelles.com. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- Napoleon's Soldiers in America, by Simone de la Souchere-Delery, 1998

- Louisiana's French Creole Culinary & Linguistic Traditions: Facts vs. Fiction Before And Since Cajunization 2013, by J. LaFleur, Brian Costello w/ Dr. Ina Fandrich

- Dr. Carl A. Brasseaux's "The Founding of New Acadia: The Beginnings of Acadian Life in Louisiana," 1765–1803

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Creole people of Louisiana. |

- French Creoles

- Louisiana Creole Dictionary

- Quadroons for Beginners: Discussing the Suppressed and Sexualized History of Free Women of Color with Author Emily Clark

- I Am What I Say I Am: Racial and Cultural Identity among Creoles of Color in New Orleans

- The creole people of New Orleans

- Creole spirit

- Cast From Their Ancestral Home, Creoles Worry About Culture's Future

- 'Faerie Folk' Strike Back With Fritters

- Left Coast Creole

- Louisiana Creole-Mexican Connection

- LA Creole

- CreoleGen

- Nsula.edu: Louisiana Creole Heritage Center website

- Loyno.edu: "Creoles" — Kate Chopin website.

- Canerivercolony.com: Cane River Colony website