United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government responsible for the enforcement of the law and administration of justice in the United States, and is equivalent to the justice or interior ministries of other countries. The department was formed in 1870 during the Ulysses S. Grant administration, and administers several federal law enforcement agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the United States Marshals Service (USMS), the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). The department is responsible for investigating instances of financial fraud, representing the United States government in legal matters (such as in cases before the Supreme Court), and running the federal prison system.[4][5] The department is also responsible for reviewing the conduct of local law enforcement as directed by the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994.[6]

Seal of the U.S. Department of Justice | |

Flag of the U.S. Department of Justice | |

The Robert F. Kennedy Building is the headquarters of the U.S. Department of Justice | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 1, 1870 |

| Type | Executive department |

| Jurisdiction | U.S. federal government |

| Headquarters | Robert F. Kennedy Department of Justice Building 950 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C., United States 38°53′36″N 77°1′30″W |

| Motto | "Qui Pro Domina Justitia Sequitur" (Latin: "Who prosecutes on behalf of justice (or the Lady Justice)"[1][2] |

| Employees | 113,114 (2019)[3] |

| Annual budget | $29.9 billion (FY 2019)[3] |

| Agency executives | |

| Website | Justice.gov |

The department is headed by the United States Attorney General, who is nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate and is a member of the Cabinet. As of February 2019, the Attorney General is William Barr.

History

The office of the Attorney General was established by the Judiciary Act of 1789 as a part-time job for one person, but grew with the bureaucracy. At one time, the Attorney General gave legal advice to the U.S. Congress, as well as the President; however, in 1819, the Attorney General began advising Congress alone to ensure a manageable workload.[7] Until March 3, 1853, the salary of the Attorney General was set by statute at less than the amount paid to other Cabinet members. Early attorneys general supplemented their salaries by running private law practices, often arguing cases before the courts as attorneys for paying litigants.[8]

Following unsuccessful efforts in 1830 and 1846 to make attorney general a full-time job,[9] in 1867, the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary, led by Congressman William Lawrence, conducted an inquiry into the creation of a "law department" headed by the Attorney General and also composed of the various department solicitors and United States attorneys. On February 19, 1868, Lawrence introduced a bill in Congress to create the Department of Justice. President Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill into law on June 22, 1870.[10]

Grant appointed Amos T. Akerman as Attorney General and Benjamin H. Bristow as America's first solicitor general the same week that Congress created the Department of Justice. The Department's immediate function was to preserve civil rights. It set about fighting against domestic terrorist groups who had been using both violence and litigation to oppose the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution.[11]

Both Akerman and Bristow used the Department of Justice to vigorously prosecute Ku Klux Klan members in the early 1870s. In the first few years of Grant's first term in office, there were 1000 indictments against Klan members with over 550 convictions from the Department of Justice. By 1871, there were 3000 indictments and 600 convictions with most only serving brief sentences while the ringleaders were imprisoned for up to five years in the federal penitentiary in Albany, New York. The result was a dramatic decrease in violence in the South. Akerman gave credit to Grant and told a friend that no one was "better" or "stronger" than Grant when it came to prosecuting terrorists.[12] George H. Williams, who succeeded Akerman in December 1871, continued to prosecute the Klan throughout 1872 until the spring of 1873, during Grant's second term in office.[13] Williams then placed a moratorium on Klan prosecutions partially because the Justice Department, inundated by cases involving the Klan, did not have the manpower to continue prosecutions.[13]

The "Act to Establish the Department of Justice" drastically increased the Attorney General's responsibilities to include the supervision of all United States attorneys, formerly under the Department of the Interior, the prosecution of all federal crimes, and the representation of the United States in all court actions, barring the use of private attorneys by the federal government.[14] The law also created the office of Solicitor General to supervise and conduct government litigation in the Supreme Court of the United States.[15]

With the passage of the Interstate Commerce Act in 1887, the federal government took on some law enforcement responsibilities, and the Department of Justice tasked with performing these.[16]

In 1884, control of federal prisons was transferred to the new department, from the Department of Interior. New facilities were built, including the penitentiary at Leavenworth in 1895, and a facility for women located in West Virginia, at Alderson was established in 1924.[17]

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order which gave the Department of Justice responsibility for the "functions of prosecuting in the courts of the United States claims and demands by, and offsenses [sic] against, the Government of the United States, and of defending claims and demands against the Government, and of supervising the work of United States attorneys, marshals, and clerks in connection therewith, now exercised by any agency or officer..."[18]

Headquarters

The U.S. Department of Justice building was completed in 1935 from a design by Milton Bennett Medary. Upon Medary's death in 1929, the other partners of his Philadelphia firm Zantzinger, Borie and Medary took over the project. On a lot bordered by Constitution and Pennsylvania Avenues and Ninth and Tenth Streets, Northwest, it holds over 1,000,000 square feet (93,000 m2) of space. The sculptor C. Paul Jennewein served as overall design consultant for the entire building, contributing more than 50 separate sculptural elements inside and outside.

Various efforts, none entirely successful, have been made to determine the original intended meaning of the Latin motto appearing on the Department of Justice seal, Qui Pro Domina Justitia Sequitur (literally "Who For Lady Justice Strives"). It is not even known exactly when the original version of the DOJ seal itself was adopted, or when the motto first appeared on the seal. The most authoritative opinion of the DOJ suggests that the motto refers to the Attorney General (and thus, by extension, to the Department of Justice) "who prosecutes on behalf of justice (or the Lady Justice)".[19]

The motto's conception of the prosecutor (or government attorney) as being the servant of justice itself finds concrete expression in a similarly-ordered English-language inscription ("THE UNITED STATES WINS ITS POINT WHENEVER JUSTICE IS DONE ITS CITIZENS IN THE COURTS") in the above-door paneling in the ceremonial rotunda anteroom just outside the Attorney General's office in the Department of Justice Main Building in Washington, D.C.[20] The building was renamed in honor of former Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in 2001. It is sometimes referred to as "Main Justice".[21]

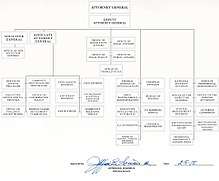

Organization

Leadership offices

- Office of the Attorney General

- Office of the Deputy Attorney General

- Office of the Associate Attorney General

- Office of the United States Principal Deputy Associate Attorney General

- Office of the Solicitor General of the United States

Divisions

| Division | Year established (as formal division) |

|---|---|

| Antitrust Division | 1933[22] |

| Civil Division (originally called the Claims Division; adopted current name on February 13, 1953)[23][24] |

1933[23] |

| Civil Rights Division | 1957[25] |

| Criminal Division | 1919[26] |

| Environment and Natural Resources Division (ENRD) (originally called the Land and Natural Resources Division; adopted current name in 1990)[27] |

1909[27] |

| Justice Management Division (JMD) (originally called the Administrative Division; adopted current name in 1985)[28] |

1945[28] |

| National Security Division (NSD) | 2007[29] |

| Tax Division | 1933[30] |

| War Division (defunct) | 1942 (disestablished 1945)[31] |

Law enforcement agencies

Several federal law enforcement agencies are administered by the Department of Justice:

- United States Marshals Service (USMS) – The office of U.S. Marshal was established by the Judiciary Act of 1789. The U.S. Marshals Service was established as an agency in 1969, and it was elevated to full bureau status under the Justice Department in 1974.[32][33]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) – On July 26, 1908, a small investigative force was created within the Justice Department under Attorney General Charles Bonaparte. The following year, this force was officially named the Bureau of Investigation by Attorney General George W. Wickersham. In 1935, the bureau adopted its current name.[34]

- Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) – the Three Prisons Act of 1891 created the federal prison system. Congress created the Federal Bureau of Prisons in 1930 by Pub. L. No. 71–218, 46 Stat. 325, signed into law by President Hoover on May 14, 1930.[35][36][37]

- National Institute of Corrections (NIC)

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) – Except for a brief period during Prohibition, ATF's predecessor bureaus were part of the Department of the Treasury for more than two hundred years.[38] ATF was first established by Department of Treasury Order No. 221, effective July 1, 1972; this order "transferred the functions, powers, and duties arising under laws relating to alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and explosives from the Internal Revenue Service to ATF.[39] In 2003, under the terms of the Homeland Security Act, ATF was split into two agencies – the new Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) was transferred to the Department of Justice, while the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) was retained by the Department of the Treasury.[38]

- Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

- Office of the Inspector General (OIG)

Offices

- Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR)

- Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys (EOUSA)

- Executive Office of the United States Trustee (EOUST)

- Office of Attorney Recruitment and Management (OARM)

- Office of the chief information officer

- In May 2014, the Department appointed Joseph Klimavicz as CIO.[40] Klimavicz succeeds Kevin Deeley, who served as acting CIO since November 2013 when the previous office holder, Luke McCormack, left to take the CIO post at the Department of Homeland Security.[40]

- Office of Dispute Resolution

- Office of the Federal Detention Trustee (OFDT)

- Office of Immigration Litigation

- Office of Information Policy

- Office of Intelligence Policy and Review (OIPR)

- Office of Intergovernmental and Public Liaison (merged with Office of Legislative Affairs on April 12, 2012)

- Office of Justice Programs (OJP)

- Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA)

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS)

- National Institute of Justice (NIJ)

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP)

- Office for Victims of Crime (OVC)

- Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking Office (SMART)

- Office of the Police Corps and Law Enforcement Education

- Office of Legal Counsel (OLC)

- Office of Legal Policy (OLP)

- Office of Legislative Affairs

- Office of the Pardon Attorney

- Office of Privacy and Civil Liberties (OPCL)

- Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR)

- Office of Public Affairs

- Office on Sexual Violence and Crimes against Children

- Office of Tribal Justice

- Office on Violence Against Women (OVW)

- Professional Responsibility Advisory Office (PRAO)

- United States Attorneys Offices

- United States Trustees Offices

- Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS)

- Community Relations Service

Other offices and programs

- Foreign Claims Settlement Commission of the United States

- INTERPOL, U.S. National Central Bureau

- National Drug Intelligence Center (former)

- Obscenity Prosecution Task Force (former)

- United States Parole Commission

In March 2003, the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service was abolished and its functions transferred to the United States Department of Homeland Security. The Executive Office for Immigration Review and the Board of Immigration Appeals, which review decisions made by government officials under Immigration and Nationality law, remain under jurisdiction of the Department of Justice. Similarly the Office of Domestic Preparedness left the Justice Department for the Department of Homeland Security, but only for executive purposes. The Office of Domestic Preparedness is still centralized within the Department of Justice, since its personnel are still officially employed within the Department of Justice.

In 2003, the Department of Justice created LifeAndLiberty.gov, a website that supported the USA PATRIOT Act. It was criticized by government watchdog groups for its alleged violation of U.S. Code Title 18 Section 1913, which forbids money appropriated by Congress to be used to lobby in favor of any law, actual or proposed.[41] The website has since been taken offline.

Finances and budget

The Justice Department authorized the budget for 2015 United States federal budget. The budget authorization is broken down as follows:[42]

| Program | Funding (in millions) |

|---|---|

| Management and Finance | |

| General Administration | $129 |

| Justice Information Sharing Technology | $26 |

Administrative Reviews and Appeals

|

$351

|

| Office of the Inspector General | $89 |

| United States Parole Commission | $13 |

| National Security Division | $92 |

| Legal Activities | |

| Office of the Solicitor General | $12 |

| Tax Division | $109 |

| Criminal Division | $202 |

| Civil Division | $298 |

| Environmental and Natural Resources Division | $112 |

| Office of Legal Counsel | $7 |

| Civil Rights Division | $162 |

| Antitrust Division | $162 |

| United States Attorneys | $1,955 |

| United States Bankruptcy Trustees | $226 |

| Law Enforcement Activities | |

| United States Marshals Service | $2,668 |

| Federal Bureau of Investigation | $8,347 |

| Drug Enforcement Administration | $2,018 |

| Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives | $1,201 |

| Federal Bureau of Prisons | $6,894 |

| Interpol-Washington Office | $32 |

| Grant Programs | |

| Office of Justice Programs | $1,427 |

| Office of Community Oriented Policing Services | $248 |

| Office on Violence Against Women | $410 |

| Mandatory Spending | |

| Mandatory Spending | $4,011 |

| TOTAL | $31,201 |

See also

References

- Revision of Original Letter Dated 14 February 1992, United States Department of Justice.

- Madan, Rafael (Fall 2008). "The Sign and Seal of Justice" (PDF). Ave Maria Law Review. 7: 123, 191–192. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- "2020 Budget Summary". The United States Department of Justice. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- "Fraud Section (FRD) | Department of Justice". Justice.gov. March 25, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- "Organization, Mission & Functions Manual: Attorney General, Deputy and Associate | DOJ | Department of Justice". Justice.gov. August 27, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- "Conduct of Law Enforcement Agencies | CRT | Department of Justice". Justice.gov. August 6, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- "United States Department of Justice: About DOJ". September 16, 2014.

- Madan, Rafael (Fall 2008). "The Sign and Seal of Justice" (PDF). Ave Maria Law Review. 7: 123, 127–136. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- Madan, Rafael (Fall 2008). "The Sign and Seal of Justice" (PDF). Ave Maria Law Review. 7: 123, 132–134. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- "Public Acts of the Forty First Congress".

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. Penguin Press. p. 700.

- Smith 2001, pp. 542–547.

- Williams (1996), The Great South Carolina Ku Klux Klan Trials, 1871–1872, p. 123

- "Act to Establish the Department of Justice". Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- "About DOJ – DOJ – Department of Justice". September 16, 2014.

- Langeluttig, Albert (1927). The Department of Justice of the United States. Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 9–14.

- Langeluttig, Albert (1927). The Department of Justice of the United States. Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 14–15.

- Executive Order 6166, Sec. 5 (June 12, 1933), at .

- Madan, Rafael (Fall 2008). "The Sign and Seal of Justice" (PDF). Ave Maria Law Review. 7: 123, 125, 191–192, 203. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- Madan, Rafael (Fall 2008). "The Sign and Seal of Justice" (PDF). Ave Maria Law Review. 7: 123, 192–203. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- "PRESIDENTIAL MEMORANDUM DIRECTS DESIGNATION OF MAIN JUSTICE BUILDING AS THE "ROBERT F. KENNEDY JUSTICE BUILDING"". U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- History of the Antitrust Division, United States Department of Justice.

- Gregory C. Sisk & Michael F. Noone, Litigation with the Federal Government (4th ed.) (American Law Institute, 2006), pp. 10–11.

- Former Assistant Attorneys General: Civil Division, U.S. Department of Justice.

- Kevin Alonso & R. Bruce Anderson, "Civil Rights Legislation and Policy" in Postwar America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History (2006, ed. James Ciment), p .233.

- Organization, Mission and Functions Manual: Criminal Division, United States Department of Justice.

- Arnold W. Reitze, Air Pollution Control Law: Compliance and Enforcement (Environmental Law Institute, 2001), p. 571.

- Cornell W. Clayton, The Politics of Justice: The Attorney General and the Making of Legal Policy (M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1992), p. 34.

- National Security Cultures: Patterns of Global Governance (Routledge, 2010; eds. Emil J. Kirchner & James Sperling), p. 195.

- Nancy Staudt, The Judicial Power of the Purse: How Courts Fund National Defense in Times of Crisis (University of Chicago Press, 2011), p. 34.

- Civilian Agency Records: Department of Justice Records, National Archived and Records Administration.

- Larry K. Gaines & Victor E. Kappeler, Policing in America (8th ed. 2015), pp. 38–39.

- United States Marshals Service Then … and Now (Office of the Director, United States Marshals Service, U.S. Department of Justice, 1978).

- The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide (Oryz Press, 1999, ed. Athan G. Theoharis), p. 102.

- Mitchel P. Roth, Prisons and Prison Systems: A Global Encyclopedia (Greenwood, 2006), pp. 278–79.

- Dean J. Champion, Sentencing: A Reference Handbook (ABC-CLIO, Inc.: 2008), pp. 22–23.

- James O. Windell, Looking Back in Crime: What Happened on This Date in Criminal Justice History? (CRC Press, 2015), p. 91.

- Transfer of ATF to U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

- Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives Bureau, Federal Register.

- Malykhina, Elena (April 25, 2014). "Justice Department Names New CIO". Government. InformationWeek.

- Dotgovwatch.com, October 18, 2007

- 2015 Department of Justice Budget Authority by Appropriation, United States Department of Justice, Accessed July 13, 2015

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States Department of Justice. |

- Official website

- United States Department of Justice at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

- Department of Justice on USAspending.gov

- USDOJ in the Federal Register

- Human Rights First; In Pursuit of Justice: Prosecuting Terrorism Cases in the Federal Courts (2009)

- Justice.gov Indictment against internet poker using UIGEA.