First Military District

The First Military District of the U.S. Army was a temporary administrative unit of the U.S. War Department that existed in the American South. The district was stipulated by the Reconstruction Acts during the Reconstruction period following the American Civil War. It only included Virginia, and was the smallest of the five military districts in terms of size. The district was successively commanded by Brigadier General John Schofield (1867–1868), Colonel George Stoneman (1868–1869) and Brigadier General Edward Canby (1869–1870).[1]

Creation of The First Military District

In March 1867, Radical Republicans in Congress became frustrated with President Andrew Johnson's Reconstruction policies, which, they believed, allowed too many former Confederate officials to hold public office in the South.[2] Politically empowered former Confederates would obstruct the civil rights of newly freed African Americans. For Republicans these rights, which would allow the antebellum ideology of abolition to translate to real freedom, were critical.

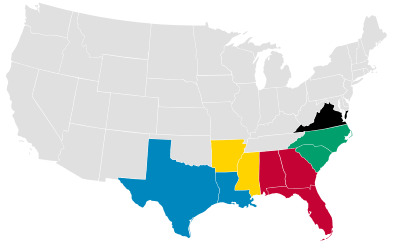

In response, Congressional Republicans passed a multitude of bills furthering strict Reconstruction policies known as the Reconstruction Acts, the most important of which being the Act to Provide for the More Efficient Government of the Rebel States. This act, passed on March 2, 1867, divided the former Confederate States (except for Tennessee, after it ratified the 14th Amendment)[3] into five separate military districts. The Reconstruction Acts required that each former Confederate state hold a Constitutional Convention, adopt a new State Constitution, and ratify the 14th Amendment before rejoining the Union. The act designated Virginia as The First Military District (also referred to as Military District No. 1).

Each of these districts fell under the command of former Union Army general officers to supervise the replacement undesirable former Confederate officials and use military force to guarantee the safety of liberated African Americans and maintain peace. However, it soon became apparent that the appointed army commanders could only act as peacekeepers until the president unveiled a proper Reconstruction policy.[4]

The military governors supervising Military District No. 1 were Major General Schofield, Major General Stoneman, and finally Brigadier General Canby until Virginia rejoined the Union in January 1870,[5] which officially ended Reconstruction in Virginia.

Under military rule

Under General Schofield

President Johnson first appointed General John Schofield as the first military governor of the district. Schofield commanded the Federal Army of the Ohio and had served with General Sherman during the last year of the war. Schofield sympathized with Virginia's social and economic leaders and was skeptical of radical proposals to allow African Americans, most of whom had little or no education, to vote or participate in politics. However, he duly issued orders to register eligible white and black men and make certain that the election was properly conducted. Under his command, African American men participated willingly in Virginia's General Assembly election in 1867.

Under General Stoneman

After Schofield became secretary of war under Johnson early in June 1868, his deputy commander in Virginia, George Stoneman, succeeded him. Unlike his predecessor, Stoneman pushed back against the Reconstruction efforts enacted by Congressional Republicans. Aligning himself with the Democratic Party, Stoneman pursued more moderate policies than the other Military Governors, which garnered him support among white Virginians.[5]

Under General Canby

Major General Edward Canby was assigned to the First Military District in April 1869, serving until September 1870. This assignment put Canby at the center of conflicts between Republicans and Democrats, whites and blacks, and state and federal governments. His role as Military Governor was concluded after Virginia ratified the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. It was under Canby's term that a committee of nine leading Conservative politicians, under the chairmanship of Alexander H. H. Stuart, negotiated a compromise allowing voters to ratify the new state constitution. Once moderate Republicans and Conservatives dominated the Virginian General Assembly after its election in 1869, the 14th and 15th Amendments were ratified shortly after. Virginia was readmitted into the union in January 1869, thus ending Reconstruction in the state and Canby's tenure.

Legacy of Military Rule

Immediate aftermath

The period of military government in Virginia preserved for African Americans some of their hard-won guarantees of citizenship. However, the degradation of these rights occurred shortly after the end of military rule. With its readmission to the Union, the district commanders relinquished their powers under the Reconstruction Acts to the civil authorities within their commands. Therefore, Conservative Party candidates regained dominance over state legislature, and returned Virginia to control of prewar leaders.

Impact on African Americans

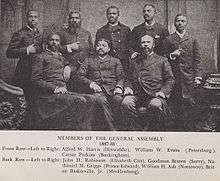

During the time after military rule, African Americans merely gained minority status in the constitutional convention, in either house of the General Assembly, or in city or county government offices. However, the Constitutional right for African Americans to vote was firmly established under military rule, which lead to the election of more than twenty African Americans to Virginia's General Assembly between 1870 and 1875.[6] While many of these African American political leaders following the end of military rule were somewhat wealthier and had more education than other African Americans, they faced many of the same difficulties and obstacles as the men who were born into slavery. They worked in jobs similar to other freedmen, such as mechanics, farmers, and ministers.[5] However, these first African American political leaders in Virginia used the guarantee of suffrage in the 15th Amendment to their full advantage and paved the path for future leaders and further struggles for equal rights to follow in their footsteps.

See also

References

- Virginia Military Governors during Reconstruction

- "First Military District". www.encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- "Mapping History : Reconstruction - Military Districts in the South: 1867". mappinghistory.uoregon.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- Bradley, Mark (2015). The Army and Reconstruction 1865-1877. pp. 13–15.

- "Library of Virginia : Civil War Research Guide - Reconstruction". www.lva.virginia.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- Jackson, Luther (1946). Negro Office-Holders in Virginia 1865-1895. Norfolk. pp. 10–15.