Mormonism and slavery

The Latter Day Saint movement has had varying and conflicting teachings on slavery. Early converts were initially from the Northern United States and opposed slavery,[1] believing they were supported by Mormon scripture.[2] After the church base moved to the slave state of Missouri and gained Southern converts, church leaders began to own slaves.[3] New scriptures were revealed teaching against interfering with the slaves of others.[4] A few slave owners joined the church, and took their slaves with them to Nauvoo, Illinois, although Illinois was a free state.[5]

After Joseph Smith's death, the church split. The largest contingent followed Brigham Young, who supported slavery, allowing enslaved men and women to be brought to the territory but prohibiting the enslavement of their descendants and requiring their consent before any move [6] and became The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). A smaller contingent followed Joseph Smith III, who opposed slavery,[7] and became the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS). Young led his followers to Utah, where he led the efforts to legalize slavery in the Utah Territory.[8] Brigham Young taught that slavery was ordained of God and taught that the Republican Party's efforts to abolish slavery went against the decrees of God and would eventually fail.[9] He also encouraged members to participate in the Indian slave trade.[10]

Teachings on slavery

Mormon scripture simultaneously denounces both slavery and abolitionism in general, teaching that it was not right for men to be in bondage to each other,[11] but that one should not interfere with the slaves of others.[4] While in Missouri, Joseph Smith defended slavery, arguing that the Old Testament taught that blacks were cursed with servitude,[12]:22 a belief that was common in America at the time.[13] While promoting the legality of slavery, the church consistently taught against the abuse of slaves and advocated for laws that provided protection.[6] Critics said the church's definition of abuse of slaves was vague and difficult to enforce.[14]

Curse of Cain and Ham

Both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young referred to the Curse of Ham to justify slavery.[3][9] According to the Bible, after Cain killed Abel, God cursed him and put a mark on him,(Genesis 4:8-15) although the Bible does not state the nature of the mark. In another biblical account, Ham discovered his father Noah drunk and naked in his tent. Because of this, Noah cursed Ham's son, Canaan to be "servants of servants".(Genesis 9:20-27) While nothing explicitly supports enslaving black Africans, one interpretation that was popular in the United States during the Atlantic slave trade was that the mark of Cain was black skin, and it was passed on through Canaan's descendants, who they believed were black Africans. They argued that because Canaan was cursed to be servants of servants, then they were justified in enslaving Canaan's descendants. By the 1800s, this interpretation was widely accepted in America,[13][15] including among Mormons. An assistant president of the church, W. W. Phelps, wrote in a letter that Ham's wife was a descendant of Cain, and that the Canaanites were black Africans and covered by both curses.[16][17][18][19]

In June 1830, Joseph Smith began translating the Bible. Parts of it were canonized as the Book of Moses and accepted as official LDS scripture in 1880. It states that "the seed of Cain were black" (Moses 7:22). The Book of Moses also discusses a group of people called the Canaanites, who were also black (Moses 7:8). These Canaanites lived before the flood, and hence before the Biblical Canaan. Later, in 1835, Smith produced a work called the Book of Abraham. It relates the story of Pharaoh, a descendant of Ham, who was also a Canaanite by birth. Pharaoh could not have the priesthood because he was "of that lineage by which he could not have the right of Priesthood,"(Abraham 1:27) and that all Egyptians descended from him (Abraham 1:22). The Book of Abraham also says the curse came from Noah (Abraham 1:26). This book was also later canonized as Mormon scripture.

In 1836, Smith taught that the Curse of Ham came from God, and that it demanded the legalization of slavery. He warned those who tried to interfere with slavery that God could do his own work.[3] While Smith never reversed his opinion on the Curse of Ham, he did start expressing more anti-slavery positions. In 1844, Smith wrote his views as a candidate for president of the United States. The anti-slavery plank of his platform called for a gradual end to slavery by the year 1850. His plan called for the government to buy the freedom of slaves using money from the sale of public lands.[20]:19

After the succession crisis, Brigham Young consistently argued slavery was a "divine institution," even after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued during the Civil War by President Abraham Lincoln. In the year following the Emancipation Proclamation, Young gave several discourses on slavery and characterized himself as neither an abolitionist nor a pro-slavery man.[21]:290 He based his position on the scriptural curses.[6][12]:40 He also used these curses to justify banning blacks from the priesthood and from holding public office.[22] After Young, leaders did not use the curse of Cain to justify slavery, but this doctrine continued to be taught by President John Taylor[23] and Bruce R. McConkie.[24] The LDS Church today does not support slavery and disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse. [25]

Most modern scholars believe "Canaanites" to refer to people of Semitic origin, not black African. Most Christian, Jewish and Muslim religions also reject the teaching that Canaanites were black Africans.[26]

Legality of slavery

While Mormon scripture taught against slavery, it also taught the importance of upholding the law. Both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young stated that the Mormons were not abolitionists.[6][27]

In the Book of Mormon, slavery was against the law.(Mosiah 2:13 & Alma 27:9) The Doctrine and Covenants teaches that "it is not right that any man should be in bondage to another" (D&C Section 101:79), but it is unclear whether it applied to black servitude, since it was never used either for or against black slavery in early discourses on slavery.[28]:13 The official position which was more often cited was the belief that one shouldn't interfere with slaves against the will of their masters, since it would cause unrest.(D&C Section 134:12) This explanation avoided taking a direct stance on slavery, and instead focused on following current laws.[28]:13 In general, Mormon teachings encouraged obeying, honoring and sustaining the laws of the land.(Articles of Faith 1:12)

In 1836, Smith wrote a piece in the Messenger and Advocate which supported slavery[12]:18 and affirmed that it was God's will.[29]:15 He said that the Northerners had no right to tell the Southerners whether they could have slaves. He said that if slavery were evil, southern "men of piety" would have objected. He expressed concern that freed slaves would overrun the United States and violate chastity and virtue. He pointed to biblical stories of slavery, arguing that the prophets who owned slaves were inspired of God, and knew more than abolitionists. He said that blacks were under the curse of Ham to be servants, and warned those who sought to free blacks were going against the dictates of God. Warren Parrish and Oliver Cowdery made similar arguments.[28]:14 During this time the Mormons were based in the slave state of Missouri.

After the move to the free state of Illinois, Smith began expressing more abolitionist ideals. He argued that blacks should be given employment opportunities equal to whites.[30] He believed that given equal chances as whites, blacks would become like whites.[31] In his personal journal, he wrote that the slaves owned by Mormons should be brought "into a free country and set ... free— Educate them and give them equal rights."[32] During Smith's 1844 campaign for president of the United States, he had advocated for the immediate abolition of slavery through compensation from money earned by the sale of public lands.[20][33]

My cogitations, like Daniel's have for a long time troubled me, when I viewed the condition of men throughout the world, and more especially in this boasted realm, where the Declaration of Independence 'holds these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness;' but at the same time some two or three millions of people are held as slaves for life, because the spirit in them is covered with a darker skin than ours.

— History of the Church, Vol. 6, Ch. 8, p.197 - p.198

Smith was killed in 1844, the year of his presidential bid, resulting in a schism among his followers. After the schism, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (later known as the Community of Christ), one of the resulting sects, embraced abolitionist ideals. Its leader following the schism, Joseph Smith III, was a "devotee" of Abraham Lincoln and supported the Republicans' charge to end slavery.[7]

Under Brigham Young, the LDS Church continued to teach that slavery was ordained of God. After he helped institute slavery in the Utah Territory, Young taught "inasmuch as we believe in the ordinances of God, in the Priesthood and order and decrees of God, we must believe in slavery".[34]:26 He argued that blacks needed to serve masters because they were not capable of ruling themselves,[35] When blacks were treated right, Young contended that they were much better off as slaves than if they were free.[34]:28 Because of these benefits, Young argued that slavery brought the "true liberty" which God had designed.[8]:110 He taught that because slavery was decreed of God, man was not able to remove it.[34]:27 He criticized the Northerners for their attempts to free the slaves contrary to the will of God and accused them of worshipping blacks. He opposed the American Civil War, calling it useless and saying that the "for the cause of human improvement is not in the least advanced by the dreadful war which now convulses our unhappy country."[9] After President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, Young prophesied that the attempts to free the slave would eventually fail.[36]

Relationship between master and slave

Slave owners complained that the Mormons were interfering with slaves, but the LDS Church denied such claims.[37]:27 In 1835, the Church issued an official statement that, because the United States government allowed slavery, the Church would not "interfere with bond-servants, neither preach the gospel to, nor baptize them contrary to the will and wish of their masters, nor meddle with or influence them in the least to cause them to be dissatisfied with their situations in this life, thereby jeopardizing the lives of men."[28] This was later adopted as scripture.(D&C Section 134:12) This policy was changed in 1836, when Smith wrote that slaves should not be taught the gospel at all until after their masters were converted.[28]:14

Church leaders taught that slaves should not be mistreated. In March 1842, Smith began studying some abolitionist literature, and stated, "it makes my blood boil within me to reflect upon the injustice, cruelty, and oppression of the rulers of the people. When will these things cease to be, and the Constitution and the laws again bear rule?" [38]

Under Brigham Young, the Church also opposed mistreatment of slaves. Young urged moderation, not to treat Africans as beasts of the field, nor to elevate them to equality with the whites, which was against God's will.[8]:109 He criticized the Southerners for their abuse of slaves, and taught that mistreating slaves should be against the law: "If the Government of the United States, in Congress assembled, had the right to pass an anti-polygamy bill, they had also the right to pass a law that slaves should not be abused as they have been; they had also a right to make a law that negroes should be used like human beings, and not worse than dumb brutes. For their abuse of that race, the whites will be cursed, unless they repent."[6] Later, as Utah sovereignty became a larger political issue, Young changed his stance on the role of the federal government in preventing abuse, arguing against federal meddling in a State's sovereignty by stating "even if we treated our slaves in an oppressive manner, it is none of their business and they ought not to meddle with it."[39]

In early Mormonism

Initially, Church leaders avoided the topic of slavery.[12]:18 Most of the early converts of the church came from the northern United States and tended to be anti-slavery.[40] These attitudes came into conflict with Southerners after they moved to Missouri.[1] In the summer of 1833 W. W. Phelps published an article in the church's newspaper, seeming to invite free black people into the state to become Mormons, and reflecting "in connection with the wonderful events of this age, much is doing towards abolishing slavery, and colonizing the blacks, in Africa."[41] Outrage followed Phelps' comments, and he was forced to reverse his position. He said he was "misunderstood" and that free blacks would not be admitted into the Church.[28]:14 His reversal did not end the controversy.[42] Missouri citizens accused Mormons of trying to interfere with their slaves. The Church denied such claims and began to teach against interfering with slaves and more pro-slavery rhetoric. Some slaves owners joined the church during this period. However, this did not end the controversy, and the church was forcibly expelled from Missouri.

By 1836, the church already had some slave owners and slaves as members. The rules established by the church for governing assemblies in the Kirtland Temple included attendees who were "bond or free, black or white." [43] When abolitionists tried to solicit support from the Mormons, they had little success.[44][45][46] Even though Illinois prohibited slavery, members who owned slaves took them along on the migration to Nauvoo. Nauvoo was reported to have 22 black members, including free and slave, between 1839–1843.[47] The state of Illinois did not pass laws to free existing slaves in the region for some time.

One slave-owning family in Nauvoo was the Flake family. They owned a slave named Green Flake. While building the Nauvoo Temple, families were asked to donate one day in ten to work on the temple. The Flake family used Green's slave labor to fulfill their tithing requirement. [5]

In The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

After Smith's death in 1844, the church went through a succession crisis, and split into multiple groups. The main body of the church, which would become the LDS Church, followed Brigham Young who was significantly more pro-slavery than Smith. Young led the Mormons to Utah and formed a theocratic government, under which slavery was legalized and the Indian slave trade was supported. Young promoted slavery,[48] teaching that blacks had been cursed to be "servants of servants" and that Indians needed slavery as part of a process of overcoming a curse placed on their Lamanite ancestors.

Slavery during westward migration

When church leaders asked for men from the members of Mississippi to help with the westward emigration, they sent four slaves with John Brown who was given the task to "take charge of them." Two of the slaves died, but Green Flake later joined the company, making it a total of three slaves arriving in Utah.[49] More slaves arrived as property of members in later companies. By 1850, 100 blacks had arrived, the majority of whom were slaves.[50] Some slaves escaped during the trek west, including one large contingent that escaped the Redd family during the night in Kansas,[51] but six of the slaves were not able to escape and continued with the family to Utah Territory.[52] When William Dennis stopped in Tabor, Iowa, members of the Underground Railroad helped five of his slaves escape, and despite a manhunt, they were able to reach freedom in Canada.[53][29]:39

Ambiguous Period (1847–1852)

Mormons arrived in Utah in the middle of the Mexican–American War; they ignored the Mexican ban on slavery. Instead, they recognized slavery as custom and consistent with the Mormon view on blacks.[54]

After the Compromise of 1850, Congress granted the Utah Territory the right to decide whether it would allow slavery based on popular sovereignty. Many prominent members of the church were slave owners, including Abraham O. Smoot and Charles C. Rich.[55]

The territory did not pass any laws defining the legality of slavery, and the LDS Church tried to remain neutral. In 1851, apostle Orson Hyde said that because many church members were coming from the South with slaves, that the church's position on the matter needed to be defined. He went on to say that there was no law in Utah prohibiting or authorizing slavery and that the decisions on the topic were to remain between slaves and their masters. He also clarified that individuals' choices on the matter were not in any way a reflection of the church as a whole or its doctrine.[56][57]:2

Once in Utah, Mormons continued to buy and sell slaves as property. Church members used their slaves to perform labor required for tithing, and sometimes donated them to the church as property.[49][29]:34 Both Young and Heber C. Kimball used the slave labor that had been donated in tithing before granting freedom to the people.[49][29]:52

In San Bernardino (1851–1856)

.jpg)

In 1851, a company of 437 Mormons under direction of Amasa M. Lyman and Charles C. Rich of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles settled at what is now San Bernardino, California. This first company took 26 slaves,[58] and more slaves were brought over as San Bernardino continued to grow.[59] Since California was a free state, the slaves should have been freed when they entered. However, slavery was openly tolerated in San Bernardino.[60] Many slaves wanted to be free,[61] but were still under the control of their masters and ignorant of the laws and their rights. Judge Benjamin Hayes freed 14 slaves who had belonged to Robert Smith.[62] Other slaves were freed by their masters.[58]

Indian slave trade

As historian Max Perry Mueller has written, the Mormons participated extensively in the Indian slave trade as part of their efforts to convert and control Utah's Native American population.[63] Mormons also were confronted in Utah with the practice of the Indian slave trade among regional tribes; it was very prevalent in the area. Tribes often took captives from enemies in raids or warfare, and used them as slaves or sold them. As the Mormons began expanding into Indian territory, they often had conflicts with the local residents. After expanding into Utah Valley, Young issued the extermination order against the Timpanogos, resulting in the Battle at Fort Utah. The Mormons took many Timpanogos women and children into slavery. Some were able to escape, but many died in slavery.[64] After expanding into Parowan, Mormons attacked a group of Indians, killing around 25 men and taking the women and children as slaves.[65]:274

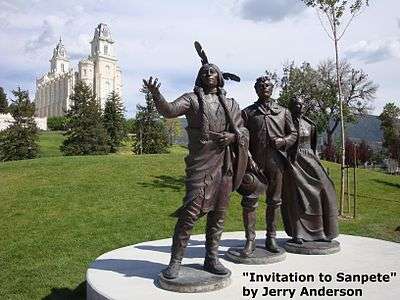

At the encouragement of Mormon leaders, their pioneers started participating in the Indian slave trade.[14][66][10] Chief Walkara, one of the main slave traders in the region, was baptized in the church. In 1851, Apostle George A. Smith gave Chief Peteetneet and Walkara talking papers that certified "it is my desire that they should be treated as friends, and as they wish to Trade horses, Buckskins and Piede children, we hope them success and prosperity and good bargains."[67]

As in other regions in the Southwest, the Mormons justified enslaving Indians in order to teach them Christianity and achieve their salvation. Mormon theology teaches that Indians are descendants in part from the Lamanites, an ancient group of people described in the Book of Mormon that had fallen into apostasy and had been cursed. When Young visited the members in Parowan, he encouraged them to "buy up the Lamanite children as fast as they could". He argued that by doing so, they could educate them and teach them the Gospel, and in a few generations the Lamanites would become "white and delightsome", as prophesied in Nephi.[68]

The Mormons strongly opposed the New Mexican slave trade.[69] Young sought to put an end to the Mexican slave trade.[70] Many of Walkara's band were upset by the interruption with the Mexican slave trade. In one graphic incident, Ute Indian Chief Arrapine, a brother of Walkara, insisted that because the Mormons had stopped the Mexicans from buying certain children, the Mormons were obligated to purchase them. In his book, Forty Years Among the Indians, Daniel Jones wrote, "[s]everal of us were present when he took one of these children by the heels and dashed its brains out on the hard ground, after which he threw the body towards us, telling us we had no hearts, or we would have bought it and saved its life."[71]

Legal period (1852–1862)

One of the Mexican slave traders, Don Pedro Leon Lujan, was charged with trading with the Indians without a license, including Indian slaves. His property was seized and his slaves distributed to Mormon families in Manti. He sued the government, charging that he received unequal treatment because he wasn't Mormon. The courts sided against him, but noted that Indian slavery had never been officially legalized in Utah.[72]

On January 5, 1852, Young, who was also Territorial Governor of Utah, addressed the joint session of the Utah Territorial Legislature. He discussed the ongoing trial of Don Pedro Leon Lujan and the importance of explicitly indicating the true policy for slavery in Utah. He explained that although he didn't think people should be treated as property, he felt because Indians were so low and degraded, that transferring them to "the more favored portions of the human race", would be a benefit and relief. He said this was superior to drudgery of Mexican slavery, because the Mexicans were "scarcely superior" to the Indians. He argued that it is proper for persons thus purchased to owe a debt to the man or woman who saved them,[73] and that it was "necessary that some law should provide for the suitable regulations under which all such indebtedness should be defrayed". He argued that this type of service was necessary and honorable to improve the condition of Indians.[74]

He also supported African slavery and said that "Inasmuch as we believe in the Bible, inasmuch as we believe in the ordinances of God, in the Priesthood and order and decrees of God, we must believe in slavery."[75] He argued that the blacks had the Curse of Ham placed on them which made them servants of servants and that he was not authorized to remove it. He also argued that blacks needed to serve masters because they are not capable of ruling themselves, and that when treated right, blacks were much better off as slaves than if they were free.[75] However, he urged moderation, not to treat Africans as beasts of the field, nor to elevate them to equality with the whites, which he believed was against the will of God.[8]:109 He said that this was the principle of true liberty according to the designs of God.[8]:110 On January 27, Orson Pratt objected to Young's remarks, saying it was not man's duty to enforce Cain's curse, and that slavery had not been authorized by God.[76] Young responded that the Lord had revealed these instructions to him.[77] After this, the Utah legislature passed an Act in Relation to Service, which officially legalized slavery in Utah Territory, and a month later passed an Act for the relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners, which specifically dealt with Indian slavery.

The acts had a few special provisions unique to slavery in Utah, reflecting Mormon beliefs. Masters were required by law to correct and punish their slaves, which particularly worried Republicans in Congress.[14] Black slaves brought into the Territory had to come "of their own free will and choice"; and they could not be sold or taken from the Territory against their will. Indian slaves just had to be in possession of a white person, which Republicans in Congress complained was too broad.[14] Indian slavery was limited to twenty years, while black slavery was limited to not be longer "than will satisfy the debt due his [master]." Several unique provisions were included which terminated the owner's contract in the event that the master neglected to feed, clothe, shelter, or otherwise abused the slave, or attempted to take them from the Territory against their will. Black slaves, but not Indian slaves, were freed if the master had sexual intercourse with them. Some schooling was also required for slaves, with blacks requiring less schooling than Indians. Despite the unique provisions in Utah, many black slaves received the same treatment as in the South. According to former slave Alexander Bankhead, the slaves were "far from being happy" and longed for their freedom.[49][51]

Mormons continued taking Indian children from their families long after the slave traders left and even began to actively solicit children from Paiute parents. They also began selling Indian slaves to each other.[78]:56 By 1853, each of the hundred households in Parowan had one or more Paiute children.[78]:57 Indian slaves were used for both domestic and manual labor.[79]:240 In 1857, Representative Justin Smith Morrill estimated that there were 400 Indian slaves in Utah.[14] Richard Kitchen has identified at least 400 Indian slaves taken into Mormon homes, but estimates even more went unrecorded because of the high mortality rate of Indian slaves. Many of them tried to escape.[65]

Brigham Young opposed slaves who wanted to escape their masters. This was enforced by Utah laws.[80] When Dan, a slave, tried to escape his master, William Camp, the courts upheld that Dan was Camp's property and could not escape. Dan was later sold to Thomas Williams for $800 and then to William Hooper.[49]

The Mormon position of slavery was often criticized and condemned by anti-slavery groups.[29]:19 In 1856, the key plank of the Republican Party's platform was "to prohibit in the territories those twin relics of barbarism, polygamy and slavery".[81] While considering appropriations for Utah Territory, Representative Justin Smith Morrill criticized the LDS Church for its laws on slavery. He said that under the Mormon patriarchy, slavery took a new shape. He criticized the use of the term servants instead of slaves and the requirement for Mormon masters to "correct and punish" their "servants". He expressed concern that Mormons might be trying to increase the number of slaves in the state.[14] Horace Greeley also criticized the Mormon position on slavery and general apathy towards the welfare of black people.[44]

Emancipation (1862–present)

When the American Civil War broke out, there is some indication that some Mormon slave owners returned to southern states because they were worried that they would lose their slaves.[51] On June 19, 1862 Congress prohibited slavery in all US territories, and on January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The slaves of the Mormons were incredibly joyful when the news reached that they were free, and many left Utah for other states, particularly California.[49][51]

After the slaves were freed, Young gave several discourses on slavery. He characterized himself as neither an abolitionist nor a pro-slavery man.[6] He criticized both the South for their abuse of slaves and the North for their alleged worshipping of blacks. He opposed the American Civil War, calling it useless and that the "cause of human improvement is not in the least advanced" by trying to free the slaves. He predicted the Emancipation Proclamation would fail.[82]

Evaluations by historians

Leaders of the church have had varying opinions on slavery, and many Mormon historians have discussed the issue.

Harris and Bringhurst noted that early Mormons wanted to stay neutral or aloof of slavery as a political issue, probably because of the strong Mormon presence in Missouri, which was then a slave state. In 1833, Joseph Smith stated that "it is not right that any man should be in bondage one to another," but most historians agree that this statement referred to debt and other types of economic bondage. In 1835, Joseph Smith wrote that missionaries should not baptize slaves against the will of their masters. According to Harris and Bringhurst, Joseph Smith made these statements to distance the church from abolitionism, and not to align with pro-slavery positions, but it came across as supporting slavery. Church headquarters were in Ohio, where abolitionism and anti-abolitionism were polarized many citizens. After members of the church were expelled from Missouri to Illinois, Smith changed to an antislavery position, which he held until his death in 1844. More new converts were from free states and a handful of black people joined the church, which may have contributed to Smith's change in position.[12]:15–19

John G. Turner writes that Brigham Young's stance on slavery was contradictory. In 1851 he opposed abolitionism, seeing it as politically radical, yet he did not want to "lay a foundation" for slavery. In an 1852 speech, Young was against slavery, but also against equal rights for blacks. Two weeks after the speech, Young pushed to have slavery formally recognized in the Utah territory, stating that he was for slavery, and said that a belief in slavery naturally followed from believing in God's priesthood and decrees. Young mimicked proslavery apologetics when he argued that slaves were better off than European workers and that slavery was mutually beneficial to slave and master. Young feared that abolishing slavery would result in blacks ruling over whites. At the end of 1852, Young commented that he was glad the black population was small. Young was generous with the black servants and slaves in his life, but that did not change their lack of rights. According to Turner, Young's position on slavery is unsurprising given the racial context of the time, as discrimination was common in white American Protestant groups. Turner does note that Young's theological justification for racial discrimination set a discriminatory precedent that his successors believed they ought to perpetuate.[83]:225–229

According to W. Paul Reeve, Brigham Young was the driving force behind the 1852 legislation to solidify slavery in the Utah territory, and that the common fear of "interracial mixing" motivated Young. Reeve also states that Mormons were surprised by the Native American slave trade from the Utes. The slave traders would insist that the Mormons buy slaves, sometimes killing a child to motivate their purchase. The 1852 law tried to change slavery into indentured servitude, requiring Mormons with Native American children to register them with their local judge and provide some education for them; the law did not work well in practice. Reeve explains that while Joseph Smith saw a potential for black equality, Young believed that blacks were inferior to whites by divine design.[17]:143–145

In the Community of Christ

Joseph Smith III, son of Joseph Smith, founded the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1860, now known as the Community of Christ. Smith was a vocal advocate of abolishing the slave trade, and followed Owen Lovejoy, an anti-slavery congressman from Illinois, and Abraham Lincoln. He joined the Republican party and advocated for their antislavery politics. He rejected the fugitive slave law, and openly stated that he would assist slaves trying to escape.[84] While he was a strong opponent of slavery, he still viewed whites as superior to blacks, and held that they must not "sacrifice the dignity, honor and prestige that may be rightfully attached to the ruling races."[7]

In the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS Church) broke from the LDS Church in the early 20th century. Although it emerged well after slavery was made illegal in the United States, there have been several accusations of slavery. On April 20, 2015, the U.S. Department of Labor assessed fines totaling $1.96 million against a group of FLDS Church members, including Lyle Jeffs, a brother of the church's controversial leader, Warren Jeffs, for alleged child slave labor violations during the church's 2012 pecan harvest at an orchard near Hurricane, Utah.[85] The church has been suspected of trafficking underage women across state lines, as well as across the US–Canada[86] and US–Mexico borders,[87] for the purpose of sometimes involuntary plural marriage and sexual slavery.[88] The FLDS is suspected by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police of having trafficked more than 30 under-age girls from Canada to the United States between the late 1990s and 2006 to be entered into polygamous marriages.[86] RCMP spokesman Dan Moskaluk said of the FLDS's activities: "In essence, it's human trafficking in connection with illicit sexual activity."[89] According to the Vancouver Sun, it's unclear whether or not Canada's anti-human trafficking statute can be effectively applied against the FLDS's pre-2005 activities, because the statute may not be able to be applied retroactively.[90] An earlier three-year-long investigation by local authorities in British Columbia into allegations of sexual abuse, human trafficking, and forced marriages by the FLDS resulted in no charges, but did result in legislative change.[91]

See also

References

- Carol L. Higham (2013). The Civil War and the West: The Frontier Transformed: The Frontier Transformed. p. 10. ISBN 9780313393594.

- http://mit.irr.org/brigham-young-we-must-believe-in-slavery-23-january-1852

- Smith, Joseph (1836). . p. 290 – via Wikisource.

As the fact is uncontrovertable, that the first mention we have of slavery is found in the holy bible ..."And he said cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren"... the people who interfere the least with the decrees and purposes of God in this matter, will come under the least condemnation before him; and those who are determined to pursue a course which shows an opposition and a feverish restlessness against the designs of the Lord, will learn, when perhaps it is too late for their own good, that God can do his own work without the aid of those who are not dictate by his counsel.

- D&C Section 134:12

- Flake, Joel. "Green Flake: His Life and Legacy" (1999) [Textual Record]. Americana Collection, Box: BX 8670.1 .F5992f 1999, p. 8. Provo, Utah: L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

- Young, Brigham (1863). . pp. 104–111 – via Wikisource.

- "The Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Community of Christ and African-American members".

- Utah Legislative Assembly (1852). Journals of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Utah, of the ... Annual Session, for the Years ..., Volume 1.

- Young, Brigham (1863). . pp. 248–250 – via Wikisource.

- Emma Green (2017). "When Mormons Aspired to Be a 'White and Delightsome' People". The Atlantic.

- D&C Section 101:79

- Harris, Matthew L.; Bringhurst, Newell G. (2015). The Mormon Church and Blacks. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-08121-7.

- Benjamin Braude, "The Sons of Noah and the Construction of Ethnic and Geographical Identities in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods," William and Mary Quarterly LIV (January 1997): 103–142. See also William McKee Evans, "From the Land of Canaan to the Land of Guinea: The Strange Odyssey of the Sons of Ham," American Historical Review 85 (February 1980): 15–43

- United States. Congress (1857). The Congressional Globe, Part 2. Blair & Rives. p. 287.

- John N. Swift and Gigen Mammoser, "'Out of the Realm of Superstition: Chesnutt's 'Dave's Neckliss' and the Curse of Ham'", American Literary Realism, vol. 42 no. 1, Fall 2009, 3

- Phelps, W. W. (1835). . p. 82 – via Wikisource.

Canaan, after he laughed at his grand father's nakedness, heired three curses: one from Cain for killing Abel; one from Ham for marrying a black wife, and one from Noah for ridiculing what God had respect for

Messenger and Advocate 1:82 - W. Paul Reeve (2015). Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199754076.

- Bush, Lester E.; Mauss, Armand L. (1984). "2". Neither White nor Black.

- John J Hammond (2012-09-12). Vol IV AN INACCESSIBLE MORMON ZION: EXPULSION FROM JACKSON COUNTY. ISBN 9781477150900.

- Bush, Lester E., Jr. (Spring 1973), "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview" (PDF), Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 8 (1): 18–19

- Watt, G. D. (1865). "The Persecutions of the Saints—Their Loyalty to the Constitution—the Mormon Battalion—the Laws of God Relative to the African Race". In Young, Brigham (ed.). Journal of Discourses Vol. 10. Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company. ISBN 9781600960154.

- Collier, Fred C., ed. (1987). The Teachings of President Brigham Young. Vol 3. 1852-1854. Salt Lake City, UT: Collier's Publishing Co. p. 46. ISBN 978-0934964012.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Journal of Discourses, Vol. 22 page 304

- McConkie, Bruce (1966). Mormon Doctrine. pp. 526–27.

- Race and the Priesthood,

The Church today disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse.

- Whitford 2009, p. 35; Ham, Sarfati & Wieland 2001.

- Smith, Joseph. "Elder's Journal, July 1832". The Joseph Smith Papers. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. p. 43. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

Are the Mormons abolitionists? No ... we do not believe in setting the Negroes free.

- Lester E. Bush, Jr (1973). Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview (PDF). Dialogue 8.

- Don B. Williams (December 2004). Slavery in Utah Territory: 1847–1865. ISBN 9780974607627.

- Joseph Smith Views of U.S. Government Archived November 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine February 7, 1844

- History of the Church, 5:217–218 Archived November 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Compilation on the Negro in Mormonism, p.40

- Arnold K. Garr, "Joseph Smith: Campaign for President of the United States", Ensign February 2002.

- Young, Brigham (1987), Collier, Fred C. (ed.), The Teachings of President Brigham Young: Vol. 3 1852–1854, Salt Lake City, Utah: Colliers Publishing Company, ISBN 0934964017, OCLC 18192348

- Young, Brigham (1863). . p. 191 – via Wikisource.

In the providences of God their ability is such that they cannot rise above the position of a servant.

- Brigham Young said, "Will the present struggle free the slave? No ... Can you destroy the decrees of the Almighty? You cannot. Yet our Christian brethren think that they are going to overthrow the sentence of the Almighty upon the seed of Ham. They cannot do that, though they may kill them by thousands and tens of thousands."Young, Brigham (1863). . pp. 248–250 – via Wikisource.

- Late persecution of the Church of Jesus Christ, of Latter Day Saints : ten thousand American citizens robbed, plundered, and banished; others imprisoned, and others martyred for their religion : with a sketch of their rise, progress and doctrine. 1840.

- History of the Church, 4:544.

- Paul Finkelman (1989). Religion and Slavery. p. 397. ISBN 9780824067960.

If Utah was admitted into the Union as a sovereign State, and we chose to introduce slavery here, it is not their business to meddle, with it; and even if we treated our slaves in an oppressive manner, it is still none of their business and they ought not to meddle with it.

- "American Prophet:The Church Early Persecutions". KPBS.

- Phelps, W.W. (July 1833), p. 109

- Bush & Mauss 1984, p. 55

- History of the Church, Vol. 2, Ch. 26, p. 368

- Horace Greeley (1860). An Overland Journey, from New York to San Francisco, in the Summer of 1859. C. M. Saxton, Barker & Company. p. 243.

I think I never heard, from the lips or journals of any of your people, one word in reprehension of that gigantic national crime and scandal, American Chattel slavery. You speak forcibly of the wrongs to which your feeble brethren have from time to time been subjected; but what are they all to the perpetual, the gigantic outrage involved in holding in abject bondage four millions of human beings?

- Joseph Smith (April 1836). "Messenger and Advocate". 2 (7): 290.

Thinking, perhaps, that the sound might go out, that "an abolitionist" had held forth several times to this community, and that the public feeling was not aroused to create mobs or disturbances, leaving the impression that all he said was concurred in, and received as gospel and the word of salvation. I am happy to say, that no violence or breach of the public peace was attempted, so far from this, that all except a very few, attended to their own avocations and left the gentleman to hold forth his own arguments to nearly naked walls.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Warren Parrish (1836). "Messenger and Advocate". 2 (7).

Not long since a gentleman of the Presbyterian faith came to this town (Kirtland) and proposed to lecture upon the abolition question. Knowing that there was a large branch of the church of Latter Day Saints in this place, who, as a people, are liberal in our sentiments; he no doubt anticipated great success in establishing his doctrine among us. But in this he was mistaken. The doctrine of Christ and the systems of men are at issue and consequently will not harmonize together.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Late Persecution of the Church of Latter-day Saints, 1840

- Jason Horowitz (February 28, 2012). "The Genesis of a church's stand on race".

- Kristen Rogers-Iversen (September 2, 2007). "Utah settlers' black slaves caught in 'new wilderness'". The Salt Lake Tribune.

- John David Smith (1997). Dictionary of Afro-American Slavery. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- "Brief History Alex Bankhead and Marinda Redd Bankhead (mention of Dr Pinney of Salem)". The Broad Ax. March 25, 1899.

- Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel:John Hardison Redd

- John Todd (1906). Early Settlement and Growth of Western Iowa; Or, Reminiscences. pp. 134–137.

- John Williams Gunnison (1852). The Mormons: Or, Latter-day Saints, in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake: a History of Their Rise and Progress, Peculiar Doctrines, Present Condition, and Prospects, Derived from Personal Observation, During a Residence Among Them. Lippincott, Grambo & Company. p. 143.

Involuntary labor by negroes is recognized by custom; those holding slaves keep them as part of their family, as they would their wives, without any law on the subject. Negro caste springs naturally from their doctrine of blacks being ineligible to the priesthood

- Slavery in Utah

- Lythgoe, Dennis L. (Fall 1967). "Negro Slavery and Mormon Doctrine". Western Humanities Review. 21 (4): 327 – via ProQuest.

- Carter, Kate B. (1965). The Story of the Negro Pioneer. Salt Lake City, Utah: Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

We feel it to be our duty to define our position in relation to the subject of slavery. There are several in the Valley of the Salt Lake from the Southern States, who have their slaves with them. There is no law in Utah to authorize slavery, neither any to prohibit it. If the slave is disposed to leave his master, no power exists there, either legal or moral, that will prevent him. But if the slave chooses to remain with his master, none are allowed to interfere between the master and the slave. All the slaves that are there appear to be perfectly contented and satisfied. When a man in the Southern states embraces our faith, the Church says to him, if your slaves wish to remain with you, and to go with you, put them not away; but if they choose to leave you, or are not satisfied to remain with you, it is for you to sell them, or let them go free, as your own conscience may direct you. The Church, on this point, assumes not the responsibility to direct. The laws of the land recognize slavery, we do not wish to oppose the laws of the country. If there is sin in selling a slave, let the individual who sells him bear that sin, and not the Church.Millennial Star, February 15, 1851.

- Nicholas R. Cataldo (1998). "Former Slave Played Major Role In San Bernardino's Early History: Lizzy Flake Rowan". City of San Bernardino.

- "The Latter-Day Saints' Millennial Star, Volume 17". p. 63.

Most of those who take slaves there pass over with them in a little while to San Bernardino ... How many slaves are now held there they could not say, but the number relatively was by no means small. A single person had taken between forty and fifty, and many had gone in with smaller numbers.

- Mark Gutglueck. "Mormons Created And Then Abandoned San Bernardino". San Bernardino County Sentinel.

- Camille Gavin (2007). Biddy Mason: A Place of Her Own. America Star Books. ISBN 9781632491909.

- Benjamin Hayes. "Mason v. Smith".

none of the said persons of color can read and write, and are almost entirely ignorant of the laws of the state of California as well as those of the State of Texas, and of their rights

- Mueller, Max (2017). Race and the Making of the Mormon People. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 158–59, 197–99. ISBN 978-1469636160.

- Farmer, Jared (2008). On Zion's Mount: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02767-1.

- Andrés Reséndez. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America.

- Ronald L. Holt. Beneath These Red Cliffs. USU Press. p. 25.

- Richard S. Van Wagoner and Steven C. Walker. A Book of Mormons.

- American Historical Company, American Historical Society (1913). Americana, Volume 8. National Americana Society. p. 83.

- "United States V. Don Pedro Leon Lujan et al.: 1851–52 – A Well-established Slave Trade". JRank.

- "United States V. Don Pedro Leon Lujan et al.: 1851–52 – Lujan Ordered Not To Trade With Indians". JRank.

- Jones, Daniel Webster (1890), Forty Years Among the Indians, Salt Lake City, Utah: Juvenile Instructor Office, p. 53, OCLC 3427232

- "United States V. Don Pedro Leon Lujan et al.: 1851–52 - Lujan Ordered Not To Trade With Indians". JRank.

- Michael Kay Bennion. "Captivity, Adoption, Marriage and Identity: Native American Children in Mormon Homes, 1847–1900". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Utah. Legislative Assembly (1852). Journals of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Utah, of the ... Annual Session, for the Years ..., Volume 1. p. 109.

- Brigham Young (January 23, 1852). "Legislative council; views on servitude bill and African slavery". Historian's Office Reports of speeches.

- Young, Margaret Blair (June 11, 2014). "A Few Words from Orson Pratt". Patheos. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- Stevenson, Russell W. (August 8, 2014). "Shouldering the Cross: How to Condemn Racism and Still Call Brigham Young a Prophet". FairMormon. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- Martha C. Knack. Boundaries Between: The Southern Paiutes, 1775–1995.

- Ned Blackhawk (2009-06-30). Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West. ISBN 9780674020993.

- Brigham Young told Greeley: "If slaves are brought here by those who owned them in the states, we do not favor their escape from the service of their owners." (see Greeley, Overland Journey 211–212) quoted in Terry L. Givens, Philip L. Barlow (September 2015). The Oxford Handbook of Mormonism. p. 383. ISBN 9780199778416.

- GOP Convention of 1856 in Philadelphia from the Independence Hall Association website

- Millennial Star, No. 50, Vol. XXV, Saturday, December 12, 1863, page 787 https://books.google.com/books?id=f0hQAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA787&lpg=PA787

- Turner, John G. (2012). Brigham Young, pioneer prophet. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 225. ISBN 9780674067318.

Brigham Young slavery.

- Roger D. Launius (1995). Joseph Smith III: Pragmatic Prophet. ISBN 9780252065156.

- "FLDS Church Members Fined $2 Million for Alleged Child Labor Violations". ABC News. 8 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- "Dozens of girls may have been trafficked to U.S. to marry". CTV News. 11 August 2011.

- Moore-Emmett, Andrea (27 July 2010). "Polygamist Warren Jeffs Can Now Marry Off Underaged Girls With Impunity". Ms. blog. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- Robert Matas (30 March 2009). "Where 'the handsome ones go to the leaders'". The Globe and Mail.

- Matthew Waller (25 November 2011). "FLDS may see more charges: International sex trafficking suspected". San Angelo Standard-Times.

- D Bramham (19 February 2011). "Bountiful parents delivered 12-year-old girls to arranged weddings". The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015.

- Martha Mendoza (15 May 2008). "FLDS in Canada may face arrests soon". Deseret News. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2012.