Slavery in China

Slavery in China has taken various forms throughout history. Slavery was abolished as a legally recognized institution, including in a 1909 law[1][2] fully enacted in 1910,[3] although the practice continued until at least 1949.[4] Illegal acts of forced labor and sexual slavery in China continue to occur in the twenty-first century[5], but those found guilty of such crimes are punished harshly.

History of Slavery in China

Shang dynasty (second millennium BC)

The earliest evidence of slavery in China dates to the Shang dynasty when, by some estimates, approximately 5 percent of the population was enslaved. The Shang dynasty engaged in frequent raids of surrounding states, capturing slaves who would be killed in ritual sacrifices. Scholars disagree as to whether these victims were also used as a source of slave labor. [6]

Warring States period (475–221 BC)

The Warring States period saw a decline in slavery from previous centuries, although it was still widespread during the period.[7] Since the introduction of private ownership of land in the state of Lu in 594 BC, which brought a system of taxation on private land, and saw the emergence of a system of landlords and peasants, the system of slavery began to decline over the following centuries, as other states followed suit.

Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC)

The Qin government confiscated property and enslaved families as punishment.[8][9] Large numbers of slaves were used by the Qin government to construct large-scale infrastructure projects, including road building, canal construction and land reclamation. Slave labor was quite extensive during this period.[10]

Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD)

One of Emperor Gao's first acts was to manumit agricultural workers enslaved during the Warring States period, although domestic servants retained their status.[1] The Han Dynasty promulgated laws to limit the possession of slaves: each king or duke was allowed a maximum of 200 slaves, an imperial princess was allowed a maximum of 100 slaves, other officials were limited to 30 slaves each.[10]

Men punished with castration during the Han dynasty were also used as slave labor.[11]

Deriving from earlier Legalist laws, the Han dynasty set in place rules penalizing criminals doing three years of hard labor or sentenced to castration by having their families seized and kept as property by the government.[12]

During the millennium long Chinese domination of Vietnam, Vietnam was a great source of slave girls who were used as sex slaves in China.[13][14]

Xin dynasty (9–23 AD)

In the year AD 9, the Emperor Wang Mang usurped the Chinese throne and, in order to deprive landowning families of their power, instituted a series of sweeping reforms, including the abolition of slavery and radical land reform. Slavery was reinstated in AD 12 before his assassination in AD 23.[15][16]

Three Kingdoms (220–280 AD)

During the Three Kingdoms period, a number of statuses intermediate between freedom and slavery developed, but none of them are thought to have exceeded 1 percent of the population.[1]

Tang dynasty (618–907 AD)

Tang law forbade enslaving free people, but allowed enslavement of criminals and foreigners.[17] Free people could however willingly sell themselves. The primary source of slaves was southern tribes, and young slave girls were the most desired. Although various officials such as Kong Kui, the governor of Guangdong, banned the practice, the trade continued.[18] Other peoples sold to Chinese included Turks, Persians, and Korean women, who were sought after by the wealthy.[19][17] The slave girls of Viet were eroticized in Tang dynasty poetry. (The term Viet(越) actually referred to southwest China. Hence in the context of the poetry (越婢脂肉滑), the words slave girl (婢) of Viet (越) more likely describe a girl from southern China than from present-day Vietnam. The poetry may therefore be misunderstood).[20]

Song dynasty (960–1279 AD)

The Song's warfare against northern and western neighbors produced many captives on both sides, but reforms were introduced to ease the transition from bondage to freedom.[1]

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368 AD)

The Yuan dynasty expanded slavery and implemented harsher terms of service.[1] In the process of the Mongol invasion of China proper, many Han Chinese were enslaved by the Mongol rulers.[21] According to Japanese historians Sugiyama Masaaki (杉山正明) and Funada Yoshiyuki (舩田善之), there were also a certain number of Mongolian slaves owned by Han Chinese during the Yuan. Moreover, there is no evidence that Han Chinese suffered particularly cruel abuse.[22]

Korean women were viewed as having white and delicate skin (肌膚玉雪發雲霧) by Hao Jingceng 郝經曾, a Yuan scholar, and it was highly desired and prestigious to own Korean female servants among the "Northerner" nobility in the Yuan dynasty as mentioned in Toghon Temür's (shùndì 順帝) Xù Zīzhì Tōngjiàn (續資治通鑒): (京师达官贵人,必得高丽女,然后为名家) and the Caomuzi (草木子) by Ye Ziqi (葉子奇) which was cited by the Jingshi ouji (京師偶記引) by Chai Sang (柴桑).[23][24]

Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD)

The Hongwu Emperor sought to abolish all forms of slavery[1] but in practice, slavery continued through the Ming dynasty.[1]

The Javans sent 300 black slaves as tribute to the Ming dynasty in 1381.[25] When the Ming dynasty crushed the Miao Rebellions in 1460, they castrated 1,565 Miao boys, which resulted in the deaths of 329 of them. They turned the survivors into eunuch slaves. The Guizhou Governor who ordered the castration of the Miao was reprimanded and condemned by Emperor Yingzong of Ming for doing it once the Ming government heard of the event.[26][27] Since 329 of the boys died, they had to castrate even more.[28] On 30 Jan 1406, the Ming Yongle Emperor expressed horror when the Ryukyuans castrated some of their own children to become eunuchs in order to give them to Yongle. Yongle said that the boys who were castrated were innocent and didn't deserve castration, and he returned the boys to Ryukyu and instructed them not to send eunuchs again.[29]

Later Ming rulers, as a way of limiting slavery because of their inability to prohibit it, passed a decree that limited the number of slaves that could be held per household and extracted a severe tax from slave owners.[1]

Qing dynasty (1644–1912 AD)

The Qing dynasty initially oversaw an expansion in slavery and states of bondage such as the booi aha.[4] They possessed about two million slaves upon their conquest of China.[1] However, like previous dynasties, the Qing rulers soon saw the advantages of phasing out slavery, and gradually introduced reforms turning slaves and serfs into peasants.[1] Laws passed in 1660 and 1681 forbade landowners from selling slaves with the land they farmed and prohibited physical abuse of slaves by landowners.[1] The Kangxi Emperor freed all the Manchus' hereditary slaves in 1685.[1] The Yongzheng Emperor's "Yongzheng emancipation" between 1723 and 1730 sought to free all slaves to strengthen his authority through a kind of social leveling that created an undifferentiated class of free subjects under the throne, freeing the vast majority of slaves.[1]

The abolition of slavery in many countries following the British emancipation led to increasing demands for cheap Chinese laborers, known as "coolies". Mistreatment ranged from the near-slave conditions maintained by some crimps and traders in the mid-1800s in Hawaii and Cuba to the relatively dangerous tasks given to the Chinese during the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad in the 1860s.[4]

Among his other reforms, Taiping Rebellion leader Hong Xiuquan abolished slavery and prostitution in the territory under his control in the 1850s and 1860s.[4]

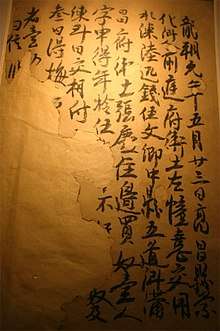

"Slavery exists in China, especially in Canton and Peking ... I have known a male slave. He is named Wang and is a native of Kansu, living in Kuei-chou in the house of his original master's son, and with his own family of four persons acknowledged to me that he was a slave, Nu-p'u. He was a person of considerable ability, but did not appear to care about being free. Female slaves are very common all over China, and are generally called . . .

YA-TOU 丫頭. Slave girl, a female slave. Slave girls are very common in China; nearly every Chinese family owns one or more slave girls generally bought from the girl's parents, but sometimes also obtained from other parties. It is a common thing for well-to-do people to present a couple of slave girls to a daughter as part of her marriage dowery. Nearly all prostitutes are slaves. It is, however, customary with respectable people to release their slave girls when marriageable. Some people sell their slave girls to men wanting a wife for themselves or for a son of theirs.

I have bought three different girls; two from Szű-chuan for a few taels each, less than fifteen dollars. One I released in Tientsin, another died in Hongkong; the other I gave in marriage to a faithful servant of mine. Some are worth much money at Shanghai."[30]

In addition to sending Han exiles convicted of crimes to Xinjiang to be slaves of Banner garrisons there, the Qing also practiced reverse exile, exiling Inner Asian (Mongol, Russian and Muslim criminals from Mongolia and Inner Asia) to China proper where they would serve as slaves in Han Banner garrisons in Guangzhou. Russian, Oirats and Muslims (Oros. Ulet. Hoise jergi weilengge niyalma) such as Yakov and Dmitri were exiled to the Han banner garrison in Guangzhou.[31]

20th century

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s the Yi people (also known as Nuosu) of China terrorized Sichuan to rob and enslave non-Nuosu including Han people. The descendants of the Han slaves, known as the White Yi (白彝), outnumbered the Black Yi (黑彝) aristocracy by ten to one.[32] There was a saying that can be translated as: "The worst insult to a Nuosu is to call him a "Han"." (To do so implied that the Nuosu's ancestors were slaves.)

21st century

Some Chinese citizens and foreigners are unlawfully kept for unfree labour or are raped.[5]

References

- Hallet, Nicole. "China and Antislavery Archived 2014-08-17 at the Wayback Machine". Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition, Vol. 1, p. 154 – 156. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007. ISBN 0-313-33143-X.

- Gang Zhou. Man and Land in Chinese History: an Economic Analysis Archived 2016-04-12 at the Wayback Machine, p. 158. Stanford University Press (Stanford), 1986. ISBN 0-8047-1271-9.

- Huang, Philip C. Code, Custom, and Legal Practice in China: the Qing and the Republic Compared Archived 2014-08-17 at the Wayback Machine, p. 17. Stanford University Press (Stanford), 2001. ISBN 0-8047-4110-7.

- Rodriguez, Junius. "China, Late Imperial Archived 2014-08-17 at the Wayback Machine". The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, Vol. 1, p. 146. ABC-CLIO, 1997. ISBN 0-87436-885-5.

- "Oppressed, enslaved and brutalised: The women trafficked from North Korea into China's sex trade". The Telegraph. May 20, 2019. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- Critical Readings on Global Slavery, Damian Alan Pargas, Felicia Roşu (ed), p 523

- The First Emperor of China by Li Yu-Ning(1975)

- Lewis 2007, p. 252.

- Society for East Asian Studies (2001). Journal of East Asian archaeology, Volume 3. Brill. p. 299. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- Junius P. Rodriguez. "China, medieval". The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery:A-K. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 147.

- History of Science Society (1952). Osiris, Volume 10. Saint Catherine Press. p. 144. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- Barbieri-Low 2007, p. 146.

- Henley, Andrew Forbes, David. Vietnam Past and Present: The North. Cognoscenti Books. ISBN 9781300568070.

- Schafer, Edward Hetzel (1967). The Vermilion Bird. University of California Press. p. 56.

slave girls of viet.

- Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2011. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-313-33143-5.

- Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, p. 420, at Google Books

- Schafer 1963, p. 44.

- Schafer 1963, p. 45.

- Benn 2002, p. 39.

- Henley, Andrew Forbes, David. e+girls+of+viet%22#v=onepage Vietnam Past and Present: The North Check

|url=value (help). Cognoscenti Books. ISBN 9781300568070. - Rodriguez, Junius P. (1997). The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery. ABC-CLIO. p. 146. ISBN 9780874368857. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

chinese slaves mongols manchu.

- Funada Yoshiyuki, "The Image of the Semu People: Mongols, Chinese, Southerners, and Various Other Peoples under the Mongol Empire", Historical and Philological Studies of China's Western Regions, p199-221, 2014(04)

- Hoong Teik Toh (2005). Materials for a Genealogy of the Niohuru Clan: With Introductory Remarks on Manchu Onomastics. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 35–. ISBN 978-3-447-05196-5. Archived from the original on 2017-04-24. Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- Tōyō Bunko (Japan). Memoirs of the Research Department. p. 63.Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko (the Oriental Library). Toyo Bunko. 1928. p. 63.

- Tsai 1996, p. 152.

- Tsai 1996, p. 16.

- Harrasowitz 1991, p. 130.

- Mitamura 1970, p. 54.

- Wade, Geoff (July 1, 2007). "Ryukyu in the Ming Reign Annals 1380s-1580s" (PDF). Working Paper Series (93). Asia Research Institute National University of Singapore: 75. SSRN 1317152. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Mesny's Chinese Miscellany, Vol. IV, 1905, p. 399.

- Yongwei, MWLFZZ, FHA 03-0188-2740-032, QL 43.3.30 (April 26, 1778).

- Ramsey 1987, p. 252.

- Du 2013, p. 150.

- Lozny 2013, p. 346.

Bibliography

| Library resources about Slavery in China |

- Abramson, Marc S. (2008), Ethnic Identity in Tang China, University of Pennsylvania Press

- Barbieri-Low, Anthony Jerome (2007), Artisans in early imperial China, University of Washington Press

- Benn, Charles (2002), Daily Life in Traditional China: The Tang Dynasty, Greenwood Press

- Du, Shanshan (2013), Women and Gender in Contemporary Chinese Societies, Lexington Books

- Harrasowitz, O. (1991), Journal of Asian History, Volume 25, O. Harrassowitz.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007), The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Lozny, Ludomir R. (2013), Continuity and Change in Cultural Adaptation to Mountain Environments, Springer

- Mitamura, Taisuke (1970), Chinese eunuchs: the structure of intimate politics, C.E. Tuttle Co.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The Languages of China, Princeton University Press

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963), The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T'ang Exotics, University of California Press

- Toh, Hoong Teik (2005), Materials for a Genealogy of the Niohuru Clan, Harrassowitz Verlag

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (1996), The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty, SUNY Press

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Slavery in China. |