Antisemitism in the United States

Antisemitism in the United States has existed for centuries. In the United States, most Jewish community relations agencies distinguish between antisemitism, which is measured in terms of attitudes and behaviors; and the security and status of American Jews, which are measured by specific incidents. FBI data shows that Jews were the most likely group to be targeted for religiously-motivated hate crimes in every year since 1991, the Anti-Defamation League said in 2019.[1] Despite this, however, antisemitic incidents were following a generally decreasing trend in the last century along with the general reduction in socially sanctioned racism in the United States since World War II and the Civil Rights Movement.

Most Americans who have been surveyed express positive viewpoints with regard to Jews.[2] An ABC News report in 2007 recounted that about 6% of Americans reported some feelings of prejudice against Jews.[3] According to surveys by the Anti-Defamation League in 2011, antisemitism is rejected by clear majorities of Americans, with 64% of them lauding Jews' cultural contributions to the nation in 2011, but a minority of them still hold hateful views towards Jews, with 19% of Americans supporting the antisemitic canard that Jews co-control Wall Street.[4] Additionally, Holocaust denial has only been a fringe phenomenon in recent years; as of April 2018, 96% of Americans are aware of the facts of the Holocaust.[5]

American viewpoints on Jews and antisemitism

Roots of American attitudes towards Jews and Jewish history in America

Krefetz (1985) asserts that antisemitism in the 1980s seems "rooted less in religion or contempt and more rooted in envy, jealousy and fear" of Jewish affluence, and the hidden power of "Jewish money".[6] Historically, antisemitic attitudes and rhetoric tend to increase when the United States is faced with a serious economic crisis.[7] Academic David Greenberg has written in Slate, "Extreme anti-communism always contained an antisemitic component: Radical, alien Jews, in their demonology, orchestrated the Communist conspiracy." He also has argued that, in the years following World War II, some groups of "the American right remained closely tied to the unvarnished antisemites of the '30s who railed against the 'Jew Deal'", a bigoted term used against the New Deal measures under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[8] American antisemites have viewed the fraudulent text The Protocols of the Elders of Zion as a real reference to a supposed Jewish cabal out to subvert and ultimately destroy the U.S.[9]

Stereotypes

The most persistent form of antisemitism has been a series of widely circulating stereotypes that construct Jews as socially, religiously, and economically unacceptable to American life. They were made to feel marginal and menacing.[10]

Martin Marger wrote, "A set of distinct and consistent negative stereotypes, some of which can be traced as far back as the Middle Ages in Europe, has been applied to Jews."[11] David Schneder wrote, "Three large clusters of traits are part of the Jewish stereotype (Wuthnow, 1982). First, [American] Jews are seen as being powerful and manipulative. Second, they are accused of dividing their loyalties between the United States and Israel. A third set of traits concerns Jewish materialistic values, aggressiveness, clannishness."[12]

Stereotypes for Jewish people share some of the content for Asians: perceived disloyalty, power, intelligence, and dishonesty overlap. The similarity in content between stereotypes of Jews and Asians may stem from the fact that many immigrant Jews and Asians both developed a merchant role, a role also historically held by many Indians in East Africa, where their stereotype content resembles that for Asians and Jews in the United States.[13]

Some of the antisemitic canards cited by the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith (ADL) in their studies of U.S. social trends include the claims that "Jews have too much power in the business world," "Jews are more willing to use shady practices to get what they want," and "Jews always like to be at the head of things." Other issues that garner attention is the assertion of excessive Jewish influence in American cinema and news media.[2]

Statistics of American viewpoints and analysis

Polls and studies point to a steady decrease in antisemitic attitudes, beliefs, and manifestations among the American public.[2][14] A 1992 survey by the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith (ADL) showed that about 20% of Americans — between 30 and 40 million adults — held antisemitic views, a considerable decline from the total of 29% found in 1964. However, another survey by the same organization concerning antisemitic incidents showed that the curve has risen without interruption since 1986.[14]

2005 survey

The number of Americans holding antisemitic views declined markedly six years later when another ADL study classified only 12 percent of the population—between 20 and 25 million adults, as "most antisemitic." Confirming the findings of previous surveys, both studies also found that African Americans were significantly more likely than whites to hold antisemitic views, with 34 percent of blacks classified as "most antisemitic," compared to 9 percent of whites in 1998.[14] The 2005 Survey of American Attitudes Towards Jews in America, a national poll of 1,600 American adults conducted in March 2005, found that 14% of Americans—or nearly 35 million adults—hold views about Jews that are "unquestionably antisemitic," compared to 17% in 2002, Previous ADL surveys over the last decade had indicated that antisemitism was in decline. In 1998, the number of Americans with hardcore antisemitic beliefs had dropped to 12% from 20% in 1992.

The 2005 survey found "35 percent of foreign-born Hispanics (down from 44% [in 2002])" and 36 percent of African-Americans hold strong antisemitic beliefs, four times more than the 9 percent for whites."[15] The 2005 Anti-Defamation League survey includes data on Hispanic attitudes, with 29% being most antisemitic (as opposed as 9% for whites and 36% for blacks), being born in the United States helped alleviate that attitude: 35% of foreign-born Hispanics and only 19% of those born in the US.[15]

The survey findings come at a time of increased antisemitic activity in America. The 2004 ADL Audit of Antisemitic Incidents reported that antisemitic incidents reached their highest level in nine years. A total of 1,821 antisemitic incidents were reported in 2004, an increase of 17% over the 1,557 incidents reported during 2003.[16] "What concerns us is that many of the gains we had seen in building a more tolerant and accepting America seem not to have taken hold as firmly as we had hoped," said Abraham H. Foxman, ADL National Director. "While there are many factors at play, the findings suggest that antisemitic beliefs endure and resonate with a substantial segment of the population, nearly 35 million people."

After 2005

In 2007 an ABC News report recounted that past ABC polls across several years have tended to find that about 6% of Americans self-report prejudice against Jews as compared to about 25% being against Arab Americans and about 10% against Hispanic Americans. The report also remarked that a full 34% of Americans reported "some racist feelings" in general as a self-description.[3]

A 2009 study entitled "Modern Anti-Semitism and Anti-Israeli Attitudes", published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in 2009, tested new theoretical model of antisemitism among Americans in the Greater New York area with three experiments. The research team's theoretical model proposed that mortality salience (reminding people that they will someday die) increases antisemitism and that antisemitism is often expressed as anti-Israel attitudes. The first experiment showed that mortality salience led to higher levels of antisemitism and lower levels of support for Israel. The study's methodology was designed to tease out antisemitic attitudes that are concealed by polite people. The second experiment showed that mortality salience caused people to perceive Israel as very important, but did not cause them to perceive any other country this way. The third experiment showed that mortality salience led to a desire to punish Israel for human rights violations but not to a desire to punish Russia or India for identical human rights violations. According to the researchers, their results "suggest that Jews constitute a unique cultural threat to many people's worldviews, that antisemitism causes hostility to Israel, and that hostility to Israel may feed back to increase antisemitism." Furthermore, "those claiming that there is no connection between antisemitism and hostility toward Israel are wrong."[17]

The 2011 Survey of American Attitudes Toward Jews in America released by the ADL found that the recent world economic recession increased some antisemitic viewpoints among Americans. Abraham H. Foxman, the organization's national director, argued, "It is disturbing that with all of the strides we have made in becoming a more tolerant society, antisemitic beliefs continue to hold a vice-grip on a small but not insubstantial segment of the American public." Specifically, the polling found that 19% of Americans answered "probably true" to the assertion that "Jews have too much control/influence on Wall Street" while 15% concurred with the related statement that Jews seem "more willing to use shady practices" in business. Nonetheless, the survey generally reported positive attitudes for most Americans, the majority of those surveyed expressed philo-Semitic sentiments such as 64% agreeing that Jews have contributed much to U.S. social culture.[4]

A 2019 survey by the Jewish Electorate Institute found that 73% of American Jews feel less secure since the election of Donald Trump to the presidency. Antisemitic attacks against synagogues since 2016 have contributed to this fear. The survey found that combatting antisemitism is a priority issue in domestic politics among American Jews, including millennials.[18]

Antisemitism within the African-American community

Surveys which were conducted by the ADL in 2007, 2009, 2011, and 2013 all found that the large majority of African-Americans who were questioned rejected antisemitism and expressed the same kinds of generally tolerant viewpoints as other Americans who were also surveyed. For example, their 2009 study reported that 28% of African-Americans surveyed displayed antisemitic views while a 72% majority did not. However, those three surveys all found that negative attitudes towards Jews were stronger among African-Americans than among the general population at large.[19]

According to earlier ADL research, going back to 1964, the trend that African-Americans are significantly more likely than white Americans to hold antisemitic beliefs across all education levels has remained over the years. Nonetheless, the percentage of the population holding negative beliefs against Jews has waned considerably in the black community during this period as well. In a 1967 New York Times Magazine article entitled "Negroes are Anti-Semitic Because They're Anti-White," the African-American author James Baldwin sought to explain the prevalence of black antisemitism.[20] An ADL poll from 1992 stated that 37% of African-Americans surveyed displayed antisemitism;[2] in contrast, a poll from 2011 found that only 29% did so.[19]

Personal backgrounds play a huge role in terms of holding prejudiced versus tolerant views. Among black Americans with no college education, 43% fell into the most antisemitic group (versus 18% for the general population) compared to that being only 27% among blacks with some college education and just 18% among blacks with a four-year college degree (versus 5% for those in the general population with a four-year college degree). That data from the ADL's 1998 polling research showed a clear pattern.[2] Although the 1998 ADL survey found a strong correlation between education level and antisemitism among African Americans, blacks at all educational levels were still more likely than whites to accept anti-Jewish stereotypes.[21]

Holocaust denial

Austin App, a German-American La Salle University professor of medieval English literature, is considered the first major American Holocaust denier.[22] App wrote extensively in newspapers and periodicals, and he also wrote a couple of books which detailed his defense of Nazi Germany and Holocaust denial. App's work inspired the Institute for Historical Review, a California center which was founded in 1978 with the sole purpose of denying the Holocaust.[23]

One of the newer forms of antisemitism is the denial of the Holocaust by revisionist historians and neo-Nazis.[24]

A survey which was conducted in 1994 by the American Jewish Committee (AJC) found that Holocaust denial was only a tiny fringe position, with 91% of respondents agreeing with the validity of the Holocaust and only 1% saying that it was possible that the holocaust had never happened.[25]

Antisemitic organizations

White supremacists

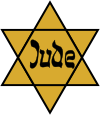

There are a number of antisemitic organizations in the United States, some of them violent, which emphasize white supremacy. These include Christian Identity Churches, White Aryan Resistance, the Ku Klux Klan, and the American Nazi Party, among others. Several fundamentalist churches, such as the Westboro Baptist Church, also preach antisemitic messages. The largest neo-Nazi organizations in the United States are the National Nazi Party and the National Socialist Movement. Many members of these antisemitic groups shave their heads and tattoo themselves with Nazi symbols such as swastikas, SS, and "Heil Hitler". Additionally, antisemitic groups march and preach antisemitic messages throughout America.[26]

Nation of Islam

A number of Jewish organizations, Christian organizations, Muslim organizations, and academics consider the Nation of Islam to be antisemitic. Specifically, they claim that the Nation of Islam has engaged in revisionist and antisemitic interpretations of the Holocaust and exaggerates the role of Jews in the Atlantic slave trade.[27] The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) alleges that the NOI Health Minister, Abdul Alim Muhammad, has accused Jewish doctors of injecting blacks with the AIDS virus.[28]

In December 2012, the Simon Wiesenthal Center put the NOI leader Louis Farrakhan on its list of the ten most prominent antisemites in the world. He was the only American to make the list. The organization cited statements that he had made in October of that year in which he claimed that "Jews control the media" and "Jews are the most violent of people".[29]

Farrakhan has denied charges of antisemitism, although his denial included a reference to "Satanic Jews." After he was banned from Facebook, he stated that those who consider him a hater don't know him personally. However, he admitted that Facebook's designation of him as a "dangerous individual" was correct.[30]

New antisemitism

In recent years some scholars have advanced the concept of New antisemitism, which is simultaneously being espoused by far leftists, far rightists, and radical Islamists, and tends to focus on opposition to the creation of a Jewish homeland in the State of Israel, and these same scholars also argue that the language of Anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel are used to attack the Jews more broadly. In their view, the proponents of the new concept believe that criticisms of Israel and Zionism are often disproportionate in degree and unique in kind, and they attribute this to antisemitism.

In the context of the "Global War on Terrorism" statements have been made by both the South Carolina Democrat Senator Ernest Hollings and the Republican populist columnist Pat Buchanan which suggest that the George W. Bush administration went to war in order to win over Israel's supporters. In 2004, a number of prominent public figures accused Jewish members of the Bush administration of tricking America into war against Saddam Hussein in order to help Israel. Hollings claimed that the US action against Saddam was undertaken "to secure Israel." Buchanan said that a "cabal" had managed "to snare our country in a series of wars that are not in America's interests."[31] Hollings wrote an editorial in the May 6, 2004 Charleston Post and Courier, where he argued that Bush invaded Iraq possibly because "spreading democracy in the Mideast to secure Israel would take the Jewish vote from the Democrats."

Noted critics of Israel, such as Noam Chomsky and Norman Finkelstein (themselves both also Jewish), question the extent of this new antisemitism in the United States. Chomsky wrote Necessary Illusions that the Anti-Defamation League casts any question of pro-Israeli policy as antisemitism, conflating and muddling issues as even Zionists receive the allegation.[32] Finkelstein stated that supposed "new antisemitism" is a preposterous concept advanced by the ADL to combat critics of Israeli policy.[33]

Antisemitism on college campuses

Many Jewish intellectuals who fled from Nazi Germany after Hitler's rise to power in the 1930s arrived in the United States. There, they hoped to continue their academic careers, but barring a scant few, they found little acceptance in elite institutions in Depression-era America with its undercurrent of antisemitism, instead, they found work in historically black colleges and universities in the American South.[34][35]

On April 3, 2006, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights announced its finding that incidents of antisemitism are a "serious problem" on college campuses throughout the United States. The Commission recommended that the U.S. Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights protect college students from antisemitism through vigorous enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and further recommended that Congress clarify that Title VI applies to discrimination against Jewish students.[36]

In February 2015, the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights under Law and Trinity College[37] presented the results of a national survey of American Jewish college students. The survey had a 10-12% response rate and it does not claim to be representative. The report showed that 54% of the 1,157 self-identified Jewish students at 55 campuses nationwide who took part in the online survey reported having experienced or witnessed antisemitism on their campuses during the Spring semester of the last academic year.

A 2017 report by Brandeis University's Steinhardt Social Research Institute indicated that most Jewish students never experience anti-Jewish remarks or physical attacks. The study, "Limits to Hostility," notes that even though it is often reported in the news, actual antisemitic hostility remains rare on most campuses and it is seldom encountered by Jewish students.[38] The study attempts to document the student experience at the campus level, by adding more detailed information to national-level surveys like the 2015 Brandeis and Trinity College Anti-semitism reports.[39]:5 The report summary highlights the finding that, even though antisemitism does exist on campus, "Jewish students do not think their campus is hostile to Jews."

The National Demographic Survey of American Jewish College Students provided a snapshot of the type, context, and location of antisemitism as it was experienced by a large national sample of Jewish students on university and four-year college campuses.[40] Inside Higher Ed focused on the more surprising findings of the report, like the fact that high rates of antisemitism were also reported at institutions regardless of their location or type, that the data which was collected after the survey suggests that discrimination occurs during low-level, everyday interpersonal activities, and Jewish students feel that their reports of antisemitism are largely ignored by the administration.[41] However, not all of the reception was positive, and The Forward argued that the study only documented a snapshot in time rather than a trend, that it did not survey a representative sample of Jewish college students and it was flawed because it allowed students to define antisemitism (leaving the term open to interpretation).[42]

Hate crimes

In April 2019, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) reported that antisemitism in the U.S. was at "near-historic levels," with 1,879 attacks recorded against individuals and institutions during 2018, "the third-highest year on record since the ADL started tracking such data in the 1970s."[43]

This followed data from earlier in the decade which showed a multi-year slide in antisemitism, including a 19% decline in 2013.[44]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) organizes Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) which are designed to collect and evaluate statistics of offenses which are committed in the U.S. In 2014, 1,140 victims of anti-religious hate crimes were listed, of which 56.8% were motivated by offenders' anti-Jewish biases. 15,494 law enforcement agencies contributed to the UCR analysis.[45][46]

However, low numbers of hate crimes against Jewish targets are also related to the relatively small size of the Jewish population in the U.S. when it is compared to the population sizes of other minority groups. According to the American Enterprise Institute, Jews were the most likely of any group, religious or otherwise, to be targeted for hate crimes in the U.S. in 2018[47], 2016[48], and 2015.[49] While The New York Times reported that Jews were the most targeted in proportion to their population size in 2005[50], and they were the second most targeted individuals after LGBT individuals in 2014[51][52].

On Saturday, October 27, 2018, an antisemitic shooter murdered 11 Jewish people in an attack on the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania during Shabbat services. It was the deadliest antisemitic act in US history.[53] The number of antisemitic hate crimes rose sharply in New York City in 2018.[54]

On April 27, 2019, a gunman killed one and injured three inside the Chabad of Poway synagogue in Poway, California.[55]

The NYPD reported a 75% increase in the amount of swastika graffiti between 2016 and 2018, with an uptick observed after the Pittsburgh shooting. Out of 189 hate crimes in New York City in 2018, 150 featured swastikas.[56] On February 1 2019 graffiti which read "fucking Jews" was found on the wall of a synagogue in LA.[57] During Hanukkah festivities in December 2019, a number of attacks which were committed in New York were possibly motivated by antisemitism, including a mass stabbing in Monsey.[58]

See also

References

- "ADL Urges Action After FBI Reports Jews Were Target of Most Religion-Based Hate Crimes in 2018". Anti-Defamation League.

- "Anti-Semitism and Prejudice in America: Highlights from an ADL Survey - November 1998". Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- "Aquí Se Habla Español – and Two-Thirds Don't Mind" (PDF). ABC News. Oct 8, 2007. Retrieved Dec 20, 2013.

- "ADL poll: Anti-Semitic attitudes on rise in USA". The Jerusalem Post. November 3, 2011. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Astor, Maggie (2018-04-12). "Holocaust Is Fading From Memory, Survey Finds". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- Krefetz, 1985

- Goldberg, Michelle. Kingdom Coming: The Rise of Christian Nationalism. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006. pp. 186-187.

- Greenberg, David (March 12, 2002). "Nixon and the Jews. Again". Slate. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- Harris, Paul (2 February 2011). "Glenn Beck and the echoes of Charles Coughlin". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America. Indiana University Press. 2006. p. 589. ISBN 978-0253346858.

- Marger, Martin N. (2008). Race and Ethnic Relations: American and Global Perspectives. Cengage Learning. p. 3234. ISBN 9780495504368.

It is the connection of Jews with money, however, that appears to be the sine qua non of anti-Semitism.

- Schneider, David J. (2004). The psychology of stereotyping. Guilford Press. p. 461. ISBN 9781572309296.

- The handbook of social psychology, Volume 2. 1998. pp. 380–381.

- "The Resuscitation of Anti-Semitism: An American Perspective - An Interview with Abraham Foxman". Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "ADL Survey: Antisemitism In America Remains Constant; 14 Percent Of Americans Hold 'Strong' Antisemitic Beliefs". Archived from the original on 7 February 2011.

- "ADL Audit: Antisemitic Incidents At Highest Level in Nine Years".

- Modern Anti-Semitism and Anti-Israeli Attitudes, Florette Cohen, Department of Psychology, The College of Staten Island, City University New York; Lee Jussim, Department of Psychology, Rutgers University, New Brunswick; Kent D. Harber, Department of Psychology, Rutgers University, Newark; Gautam Bhasin, Department of Counseling, Columbia Teacher's College, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2009, Vol. 97, No. 2, 290–306 psycnet.apa.org

- "Poll: Domestic Issues Dominate The Priorities Of The Jewish Electorate." Jewish Electorate Institute. 22 May 2019. 22 May 2019.

- "ADL 2011 Antisemitism Presentation" (PDF). Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-12. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- "To what degree does Anti-Semitism among African Americans simply reflect Anti-White sentiment?". Archived from the original on 2007-10-20.

- "ADL Survey Finds Anti-Semitism ...." Jewish Virtual Library. November 1998. 23 May 2019.

- Atkins, Stephen E. (2009). Austin J. App and Holocaust Denial. Holocaust denial as an international movement. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. pp. 153–55. ISBN 0-313-34539-2.

- Carlos C. Huerta and Dafna Shiffman-Huerta "Holocaust Denial Literature: Its Place in Teaching the Holocaust", in Rochelle L. Millen. New Perspectives on the Holocaust: A Guide for Teachers and Scholars, NYU Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8147-5540-2, p. 189.

- Antisemitism In The Contemporary World. Edited by Michael Curtis. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1986, 333 pp., $42.50. ISBN 0-8133-0157-2.

- Kagay, Michael R. (July 8, 1994). "Poll on Doubt Of Holocaust Is Corrected". Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- "Extremism in America - About Westboro Baptist Church".

- "H-Antisemitism - H-Net".

- Nation of Islam Archived 2006-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- "Wiesenthal ranks top 10 anti-Semites, Israel-haters".

- McCann, Herbert G. "Farrakhan delivers insult while denying he’s anti-Semitic." Associated Press News. 10 May 2019. 17 January 2020.

- Rafael Medoff, President Lindbergh? Roth's New Novel Raises Questions About Antisemitism in the 1940s--and Today Archived 2008-03-23 at the Wayback Machine, David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, September 2004. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- Noam Chomsky, Necessary Illusions, Appendix V, Segment 20

- "Congressmember Weiner Gets It Wrong On Palestinian Group He Tried To Bar From U.S." Democracy Now!. 2006-08-30. Archived from the original on 2007-11-14.

- "Jewish Prof's and HBCU's - African American Registry". African American Registry. Retrieved 2018-12-24.

- Hoch, Paul K. (1983-05-11). "The reception of central European refugee physicists of the 1930s: USSR, UK, US". Annals of Science. 40 (3): 217–246. doi:10.1080/00033798300200211. ISSN 0003-3790.

- U.S. Commission on Civil Rights: "Findings and Recommendations Regarding Campus Antisemitism" (PDF). (19.3 KiB). April 3, 2006

- Kosmin, Barry; Keysar, Ariela. "Anti-Semitism Report" (PDF). Louis D. Brandeis Center. Louis D. Brandeis Cent for Human Rights Under Law. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-03-18.

- Lipman, Steve (18 December 2017). "What Anti-Semitism On Campus?". The New York Jewish Week. The Jewish Week Media Group. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Wright, Graham; Shain, Michelle; Hecht, Shahar; Saxe, Leonard (December 2017). "The Limits of Hostility:Students Report on Antisemitism and Anti-Israel Sentiment at Four US Universities" (PDF). Brandeis University. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "National Survey of U.S. Jewish College Students Shows High Rate of Anti-Semitism on Campuses". Trinity College. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Mulhere, Kaitlin. "Campus Anti-Semitism". Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Ulinich, Anya. "The Anti-Semitism Surge That Isn't". The Forward. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- "Anti-Semitic Incidents Remained at Near-Historic Levels in 2018; Assaults Against Jews More Than Doubled". Anti-Defamation League.

- "ADL Audit: Anti-Semitic Incidents Declined 19 Percent Across the United States in 2013". ADL. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Latest Hate Crime Statistics Available".

- "Victims".

- "New 2018 FBI data: Jews were 2.7X more likely than blacks, 2.2X more likely than Muslims to be hate crime victims". American Enterprise Institute - AEI. 14 November 2019.

- "2016 FBI data: Jews were 3X more likely than blacks, 1.5X more likely than Muslims to be hate crime victims". American Enterprise Institute - AEI. 13 November 2017.

- https://www.aei.org/carpe-diem/2015-fbi-data-jews-were-nearly-3x-more-likely-than-blacks-1-5x-more-likely-than-muslims-to-be-a-hate-crime-victim/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Park, Haeyoun; Mykhyalyshyn, Iaryna (16 June 2016). "L.G.B.T. People Are More Likely to Be Targets of Hate Crimes Than Any Other Minority Group". The New York Times.

- Park, Haeyoun; Mykhyalyshyn, Iaryna (16 June 2016). "L.G.B.T. People Are More Likely to Be Targets of Hate Crimes Than Any Other Minority Group". The New York Times.

- "Interesting facts of the day on US hate crimes in 2014". American Enterprise Institute - AEI. 6 December 2015.

- "Why Pittsburgh matters - Religion News Service". Religion News Service. 28 October 2018. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- Liphshiz, Cnaan (28 December 2018). "Hate crimes in NY: Jews targeted in 2018 more than all other groups combined". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- "Poway synagogue shooting". Wikipedia. 4 January 2020.

- "Hate crimes in NY: Jews targeted in 2018 more than all other groups combined". Forward. 23 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- "Anti-Semitic graffiti found on LA synagogue". The Times of Israel. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- "Synagogue stabbings: five hurt in Monsey attack, say reports". The Guardian. December 28, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

Further reading

- Buckley, William F. In Search of Anti-Semitism, New York: Continuum, 1992

- Carr, Steven Alan. Hollywood and anti-Semitism: A cultural history up to World War II, Cambridge University Press 2001

- Dershowitz, Alan M. Chutzpah 1st ed., Boston: Little, Brown, c1991

- Dinnerstein, Leonard. Antisemitism in America, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994

- Dinnerstein, Leonard Uneasy at Home: Antisemitism and the American Jewish Experience, New York: Columbia University Press, 1987.

- Dolan, Edward F. Anti-Semitism, New York: F. Watts, 1985.

- Extremism on the Right: A Handbook New revised edition, New York: Anti Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, 1988.

- Flynn, Kevin J. and Gary Gerhardt The Silent Brotherhood: Inside America's Racist Underground, New York: Free Press; London: Collier Macmillan, c1989

- Ginsberg, Benjamin The Fatal Embrace: Jews and the State, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, c1993

- Hate Groups in America: a Record of Bigotry and Violence, New rev. ed. New York: Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, c1988

- Hirsch, Herbert and Jack D. Spiro, eds. Persistent Prejudice: Perspectives on Anti-Semitism, Fairfax, Va.: George Mason University Press; Lanham, MD: Distributed by arrangement with University Pub. Associates, c1988

- Jaher, Frederic Cople A Scapegoat in the Wilderness: The Origins and Rise of Anti-Semitism in America, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994

- Lang, Susan S. Extremist Groups in America, New York: F. Watts, 1990

- Lee, Albert Henry Ford and the Jews, New York: Stein and Day, 1980

- Lipstadt, Deborah E. Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory, New York: Free Press; Toronto: Maxwell Macmillan Canada; New York: Maxwell Macmillan International, 1993

- Rausch, David A. Fundamentalist-evangelicals and Anti-semitism, 1st ed. Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1993

- Ridgeway, James Blood in the Face: The Ku Klux Klan, Aryan Nations, Nazi Skinheads and the Rise of a New White Culture, New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1990

- Roth, Philip The Plot Against America, Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2004

- Tobin, Gary A. and Sharon L. Sassler Jewish Perceptions of Antisemitism, New York: Plenum Press, c1988

- Volkman, Ernest A Legacy of Hate: Anti-Semitism in America, New York: F. Watts, 1982

External links

- State of the Nation: Anti-Semitism and the economic crisis by Neil Malhotra and Yotam Margalit in Boston Review