Foreign policy of the United States

The foreign policy of the United States is its interactions with foreign nations and how it sets standards of interaction for its organizations, corporations and system citizens of the United States.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the United States |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The officially stated goals of the foreign policy of the United States of America, including all the Bureaus and Offices in the United States Department of State,[1] as mentioned in the Foreign Policy Agenda of the Department of State, are "to build and sustain a more democratic, secure, and prosperous world for the benefit of the American people and the international community".[2] In addition, the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs states as some of its jurisdictional goals: "export controls, including nonproliferation of nuclear technology and nuclear hardware; measures to foster commercial interaction with foreign nations and to safeguard American business abroad; international commodity agreements; international education; and protection of American citizens abroad and expatriation".[3] U.S. foreign policy and foreign aid have been the subject of much debate, praise and criticism, both domestically and abroad.

Powers of the President

The President sets the tone for all foreign policy. The State Department and all members design and implement all details to the President's policy. The Congress approves the President's picks for ambassadors and as a secondary function, can declare war. The President of the United States negotiates treaties with foreign nations, then treaties enter into force only if ratified by two-thirds of the Senate. The President is also Commander in Chief of the United States Armed Forces, and as such has broad authority over the armed forces. Both the Secretary of State and ambassadors are appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate. The United States Secretary of State acts similarly to a foreign minister and under the President's leadership, is the primary conductor of state-to-state diplomacy.

Powers of the Congress

Congress is the only branch of government that has the authority to declare war. Furthermore, Congress writes the civilian and military budget, thus has vast power in military action and foreign aid. Congress also has power to regulate commerce with foreign nations.[4]

Historical overview

The main trend regarding the history of U.S. foreign policy since the American Revolution is the shift from non-interventionism before and after World War I, to its growth as a world power and global hegemony during and since World War II and the end of the Cold War in the 20th century.[5] Since the 19th century, U.S. foreign policy also has been characterized by a shift from the realist school to the idealistic or Wilsonian school of international relations.[6]

Foreign policy themes were expressed considerably in George Washington's farewell address; these included, among other things, observing good faith and justice towards all nations and cultivating peace and harmony with all, excluding both "inveterate antipathies against particular nations, and passionate attachments for others", "steer[ing] clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world", and advocating trade with all nations. These policies became the basis of the Federalist Party in the 1790s, but the rival Jeffersonians feared Britain and favored France in the 1790s, declaring the War of 1812 on Britain. After the 1778 alliance with France, the U.S. did not sign another permanent treaty until the North Atlantic Treaty in 1949. Over time, other themes, key goals, attitudes, or stances have been variously expressed by Presidential 'doctrines', named for them. Initially these were uncommon events, but since WWII, these have been made by most presidents.

Jeffersonians vigorously opposed a large standing army and any navy until attacks against American shipping by Barbary corsairs spurred the country into developing a naval force projection capability, resulting in the First Barbary War in 1801.[7]

Despite two wars with European Powers—the War of 1812 and the Spanish–American War in 1898—American foreign policy was mostly peaceful and marked by steady expansion of its foreign trade during the 19th century. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 doubled the nation's geographical area; Spain ceded the territory of Florida in 1819; annexation brought in the independent Texas Republic in 1845; a war with Mexico added California, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and New Mexico in 1848. The U.S. bought Alaska from the Russian Empire in 1867, and it annexed the independent Republic of Hawaii in 1898. Victory over Spain in 1898 brought the Philippines and Puerto Rico, as well as oversight of Cuba. The short experiment in imperialism ended by 1908, as the U.S. turned its attention to the Panama Canal and the stabilization of regions to its south, including Mexico.

20th century

World War I

The 20th century was marked by two world wars in which Allied powers, along with the United States, defeated their enemies, and through this participation the United States increased its international reputation. Entry into the First World War was a hotly debated issue in the 1916 presidential election.[8]

President Wilson's Fourteen Points was developed from his idealistic Wilsonianism program of spreading democracy and fighting militarism to prevent future wars. It became the basis of the German Armistice (which amounted to a military surrender) and the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. The resulting Treaty of Versailles, due to European allies' punitive and territorial designs, showed insufficient conformity with these points, and the U.S. signed separate treaties with each of its adversaries; due to Senate objections also, the U.S. never joined the League of Nations, which was established as a result of Wilson's initiative. In the 1920s, the United States followed an independent course, and succeeded in a program of naval disarmament, and refunding the German economy. Operating outside the League it became a dominant player in diplomatic affairs. New York became the financial capital of the world,[9] but the Wall Street Crash of 1929 hurled the Western industrialized world into the Great Depression. American trade policy relied on high tariffs under the Republicans, and reciprocal trade agreements under the Democrats, but in any case exports were at very low levels in the 1930s.

World War II

The United States adopted a non-interventionist foreign policy from 1932 to 1938, but then President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved toward strong support of the Allies in their wars against Germany and Japan. As a result of intense internal debate, the national policy was one of becoming the Arsenal of Democracy, that is financing and equipping the Allied armies without sending American combat soldiers. Roosevelt mentioned four fundamental freedoms, which ought to be enjoyed by people "everywhere in the world"; these included the freedom of speech and religion, as well as freedom from want and fear. Roosevelt helped establish terms for a post-war world among potential allies at the Atlantic Conference; specific points were included to correct earlier failures, which became a step toward the United Nations. American policy was to threaten Japan, to force it out of China, and to prevent its attacking the Soviet Union. However, Japan reacted by an attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and the United States was at war with Japan, Germany, and Italy. Instead of the loans given to allies in World War I, the United States provided Lend-Lease grants of $50,000,000,000. Working closely with Winston Churchill of Britain, and Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union, Roosevelt sent his forces into the Pacific against Japan, then into North Africa against Italy and Germany, and finally into Europe starting with France and Italy in 1944 against the Germans. The American economy roared forward, doubling industrial production, and building vast quantities of airplanes, ships, tanks, munitions, and, finally, the atomic bomb. Much of the American war effort went to strategic bombers, which flattened the cities of Japan and Germany.

Cold War

After the war, the U.S. rose to become the dominant economic power with broad influence in much of the world, with the key policies of the Marshall Plan and the Truman Doctrine. Almost immediately, however, the world witnessed division into broad two camps during the Cold War; one side was led by the U.S. and the other by the Soviet Union, but this situation also led to the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement. This period lasted until almost the end of the 20th century and is thought to be both an ideological and power struggle between the two superpowers. Policies of linkage and containment were adopted to limit Soviet expansion, and a series of proxy wars were fought with mixed results. In 1991, the Soviet Union dissolved into separate nations, and the Cold War formally ended as the United States gave separate diplomatic recognition to the Russian Federation and other former Soviet states.

In domestic politics, foreign policy is not usually a central issue. In 1945–1970 the Democratic Party took a strong anti-Communist line and supported wars in Korea and Vietnam. Then the party split with a strong, "dovish", pacifist element (typified by 1972 presidential candidate George McGovern). Many "hawks", advocates for war, joined the Neoconservative movement and started supporting the Republicans—especially Reagan—based on foreign policy.[10] Meanwhile, down to 1952 the Republican Party was split between an isolationist wing, based in the Midwest and led by Senator Robert A. Taft, and an internationalist wing based in the East and led by Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower defeated Taft for the 1952 nomination largely on foreign policy grounds. Since then the Republicans have been characterized by a hawkish and intense American nationalism, strong opposition to Communism, and strong support for Israel.[11]

21st century

In the 21st century, U.S. influence remains strong but, in relative terms, is declining in terms of economic output compared to rising nations such as China, India, Russia, and the newly consolidated European Union. Substantial problems remain, such as climate change, nuclear proliferation, and the specter of nuclear terrorism. Foreign policy analysts Hachigian and Sutphen in their book The Next American Century suggest all five powers have similar vested interests in stability and terrorism prevention and trade; if they can find common ground, then the next decades may be marked by peaceful growth and prosperity.[12]

.jpg)

In 2017 diplomats from other countries developed new tactics to deal with President Donald Trump. The New York Times reported on the eve of his first foreign trip as president:

- For foreign leaders trying to figure out the best way to approach an American president unlike any they have known, it is a time of experimentation. Embassies in Washington trade tips and ambassadors send cables to presidents and ministers back home suggesting how to handle a mercurial, strong-willed leader with no real experience on the world stage, a preference for personal diplomacy and a taste for glitz....certain rules have emerged: Keep it short — no 30-minute monologue for a 30-second attention span. Do not assume he knows the history of the country or its major points of contention. Compliment him on his Electoral College victory. Contrast him favorably with President Barack Obama. Do not get hung up on whatever was said during the campaign. Stay in regular touch. Do not go in with a shopping list but bring some sort of deal he can call a victory.[13]

Trump has numerous aides giving advice on foreign policy. The chief diplomat was Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. His major foreign policy positions were often at odds with Trump, including:

- urging the United States to stay in the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Paris climate accord, taking a hard line on Russia, advocating negotiations and dialogue to defuse the mounting crisis with North Korea, advocating for continued U.S. adherence to the Iran nuclear deal, taking a neutral position in the dispute between Qatar and Saudi Arabia, and reassuring jittery allies, from South Korea and Japan to our NATO partners, that America still has their back.[14]

Law

In the United States, there are three types of treaty-related law:

- Treaties are formal written agreements specified by the Treaty Clause of the Constitution. The President makes a treaty with foreign powers, but then the proposed treaty must be ratified by a two-thirds vote in the Senate. For example, President Wilson proposed the Treaty of Versailles after World War I after consulting with allied powers, but this treaty was rejected by the Senate; as a result, the U.S. subsequently made separate agreements with different nations. While most international law has a broader interpretation of the term treaty, the U.S. sense of the term is more restricted. In Missouri v. Holland, the Supreme Court ruled that the power to make treaties under the U.S. Constitution is a power separate from the other enumerated powers of the federal government, and hence the federal government can use treaties to legislate in areas which would otherwise fall within the exclusive authority of the states.

- Executive agreements are made by the President—in the exercise of his Constitutional executive powers—alone.

- Congressional-executive agreements are made by the President and Congress. A majority of both houses makes it binding much like regular legislation after it is signed by the president. The Constitution does not expressly state that these agreements are allowed, and constitutional scholars such as Laurence Tribe think they are unconstitutional.[15]

In contrast to most other nations, the United States considers the three types of agreements as distinct. Further, the United States incorporates treaty law into the body of U.S. federal law. As a result, Congress can modify or repeal treaties afterward. It can overrule an agreed-upon treaty obligation even if that is seen as a violation of the treaty under international law. Several U.S. court rulings confirmed this understanding, including Supreme Court decisions in Paquete Habana v. the United States (1900), and Reid v. Covert (1957), as well as a lower court ruling in Garcia-Mir v. Meese (1986). Further, the Supreme Court has declared itself as having the power to rule a treaty as void by declaring it "unconstitutional" although as of 2011, it has never exercised that power.

The State Department has taken the position that the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties represents established law. Generally, when the U.S. signs a treaty, it is binding. However, as a result of the Reid v. Covert decision, the U.S. adds a reservation to the text of every treaty that says in effect that the U.S. intends to abide by the treaty but that if the treaty is found to be in violation of the Constitution, the U.S. legally is then unable to abide by the treaty since the U.S. signature would be ultra vires.

International agreements

The United States has ratified and participates in many other multilateral treaties, including arms control treaties (especially with the Soviet Union), human rights treaties, environmental protocols, and free trade agreements.

Economic and general government

The United States is a founding member of the United Nations and most of its specialized agencies, notably the World Bank Group and International Monetary Fund. The U.S. has at times withheld payment of dues, owing to disagreements with the UN.

The United States is also member of:

- Organization of American States

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)

- NAFTA, the regional trade bloc with Canada and Mexico

- World Trade Organization

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)

- Group of Seven (G7)

- World Customs Organization

Freely Associated States

After it captured the islands from Japan during World War II, the United States administered the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands from 1947 to 1986 (1994 for Palau). The Northern Mariana Islands became a U.S. territory (part of the United States), while Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau became independent countries. Each has signed a Compact of Free Association that gives the United States exclusive military access in return for U.S. defense protection and conduct of military foreign affairs (except the declaration of war) and a few billion dollars of aid. These agreements also generally allow citizens of these countries to live and work in the United States with their spouses (and vice versa), and provide for largely free trade. The federal government also grants access to services from domestic agencies, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency, National Weather Service, the United States Postal Service, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Federal Communications Commission, and U.S. representation to the International Frequency Registration Board of the International Telecommunication Union.

Non-participation in multi-lateral agreements

The United States notably does not participate in various international agreements adhered to by almost all other industrialized countries, by almost all the countries of the Americas, or by almost all other countries in the world. With a large population and economy, on a practical level this can undermine the effect of certain agreements,[16][17] or give other countries a precedent to cite for non-participation in various agreements.[18]

In some cases the arguments against participation include that the United States should maximize its sovereignty and freedom of action, or that ratification would create a basis for lawsuits that would treat American citizens unfairly.[19] In other cases, the debate became involved in domestic political issues, such as gun control, climate change, and the death penalty.

Examples include:

- Versailles Treaty and the League of Nations covenant (in force 1920–45, signed but not ratified)

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (took effect in 1976, ratified with substantial reservations)

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (took effect in 1976, signed but not ratified)

- American Convention on Human Rights (took effect in 1978)

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (took effect in 1981, signed but not ratified)

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (took effect in 1990, signed but not ratified)

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (took effect in 1994)

- Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (signed in 1996 but never ratified and never took effect)

- Mine Ban Treaty (took effect in 1999)

- International Criminal Court (took effect in 2002)

- Kyoto Protocol (in force 2005–12, signed but not ratified)

- Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (took effect in 2006)

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (took effect in 2008, signed but not ratified)

- Convention on Cluster Munitions (took effect in 2010)

- International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (took effect in 2010)

- Arms Trade Treaty (took effect in 2014)

- Other human rights treaties

Hub and spoke vs multilateral

While America's relationships with Europe have tended to be in terms of multilateral frameworks, such as NATO, America's relations with Asia have tended to be based on a "hub and spoke" model using a series of bilateral relationships where states coordinate with the United States and do not collaborate with each other.[20] On May 30, 2009, at the Shangri-La Dialogue Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates urged the nations of Asia to build on this hub and spoke model as they established and grew multilateral institutions such as ASEAN, APEC and the ad hoc arrangements in the area.[21] However, in 2011 Gates said that the United States must serve as the "indispensable nation," for building multilateral cooperation.[22]

Oil

Persian Gulf

As of 2014, the U.S. currently produces about 66% of the oil that it consumes.[23] While its imports have exceeded domestic production since the early 1990s, new hydraulic fracturing techniques and discovery of shale oil deposits in Canada and the American Dakotas offer the potential for increased energy independence from oil exporting countries such as OPEC.[24] Former U.S. President George W. Bush identified dependence on imported oil as an urgent "national security concern".[25]

Two-thirds of the world's proven oil reserves are estimated to be found in the Persian Gulf.[26][27] Despite its distance, the Persian Gulf region was first proclaimed to be of national interest to the United States during World War II. Petroleum is of central importance to modern armies, and the United States—as the world's leading oil producer at that time—supplied most of the oil for the Allied armies. Many U.S. strategists were concerned that the war would dangerously reduce the U.S. oil supply, and so they sought to establish good relations with Saudi Arabia, a kingdom with large oil reserves.[28]

The Persian Gulf region continued to be regarded as an area of vital importance to the United States during the Cold War. Three Cold War United States Presidential doctrines—the Truman Doctrine, the Eisenhower Doctrine, and the Nixon Doctrine—played roles in the formulation of the Carter Doctrine, which stated that the United States would use military force if necessary to defend its "national interests" in the Persian Gulf region.[29] Carter's successor, President Ronald Reagan, extended the policy in October 1981 with what is sometimes called the "Reagan Corollary to the Carter Doctrine", which proclaimed that the United States would intervene to protect Saudi Arabia, whose security was threatened after the outbreak of the Iran–Iraq War.[30] Some analysts have argued that the implementation of the Carter Doctrine and the Reagan Corollary also played a role in the outbreak of the 2003 Iraq War.[31][32][33][34]

Canada

Almost all of Canada's energy exports go to the United States, making it the largest foreign source of U.S. energy imports: Canada is consistently among the top sources for U.S. oil imports, and it is the largest source of U.S. natural gas and electricity imports.[35]

Africa

In 2007 the U.S. was Sub-Saharan Africa's largest single export market accounting for 28% of exports (second in total to the EU at 31%). 81% of U.S. imports from this region were petroleum products.[36]

Foreign aid

Foreign assistance is a core component of the State Department's international affairs budget, which is $49 billion in all for 2014.[37] Aid is considered an essential instrument of U.S. foreign policy. There are four major categories of non-military foreign assistance: bilateral development aid, economic assistance supporting U.S. political and security goals, humanitarian aid, and multilateral economic contributions (for example, contributions to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund).[38]

In absolute dollar terms, the United States government is the largest international aid donor ($23 billion in 2014).[37] The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) manages the bulk of bilateral economic assistance; the Treasury Department handles most multilateral aid. In addition many private agencies, churches and philanthropies provide aid.

Although the United States is the largest donor in absolute dollar terms, it is actually ranked 19 out of 27 countries on the Commitment to Development Index. The CDI ranks the 27 richest donor countries on their policies that affect the developing world. In the aid component the United States is penalized for low net aid volume as a share of the economy, a large share of tied or partially tied aid, and a large share of aid given to less poor and relatively undemocratic governments.

Foreign aid is a highly partisan issue in the United States, with liberals, on average, supporting foreign aid much more than conservatives do.[39]

Military

As of 2016, the United States is actively conducting military operations against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and Al-Qaeda under the Authorization for Use of Military Force of 2001, including in areas of fighting in the Syrian Civil War and Yemeni Civil War. The Guantanamo Bay Naval Base holds what the federal government considers unlawful combatants from these ongoing activities, and has been a controversial issue in foreign relations, domestic politics, and Cuba–United States relations. Other major U.S. military concerns include stability in Afghanistan and Iraq after the recent U.S.–led invasions of those countries, Russian military activity in Ukraine and Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen.

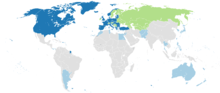

Mutual defense agreements

The United States is a founding member of NATO, an alliance of 29 North American and European nations formed to defend Western Europe against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Under the NATO charter, the United States is compelled to defend any NATO state that is attacked by a foreign power. The United States itself was the first country to invoke the mutual defense provisions of the alliance, in response to the September 11 attacks.

The United States also has mutual military defense treaties with:[40]

- Australia and New Zealand

- Japan

- South Korea

- Philippines

- Thailand, with other states formerly in the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization

- Most countries in South America, Central America, and the Caribbean, through the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance

The United States has responsibility for the defense of the three Compact of Free Association states: Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau.

Other allies and multilateral organizations

In 1989, the United States also granted five nations the major non-NATO ally status (MNNA), and additions by later presidents have brought the list to 30 nations. Each such state has a unique relationship with the United States, involving various military and economic partnerships and alliances.

and lesser agreements with:

The U.S. participates in various military-related multi-lateral organizations, including:

The U.S. also operates hundreds of military bases around the world.

Unilateral vs. multilateral military actions

The United States has undertaken unilateral and multilateral military operations throughout its history (see Timeline of United States military operations). In the post-World War II era, the country has had permanent membership and veto power in the United Nations Security Council, allowing it to undertake any military action without formal Security Council opposition. With vast military expenditures, the United States is known as the sole remaining superpower after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The U.S. contributes a relatively small number of personnel for United Nations peacekeeping operations. It sometimes acts through NATO, as with the NATO intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina, NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, and ISAF in Afghanistan, but often acts unilaterally or in ad-hoc coalitions as with the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The United Nations Charter requires that military operations be either for self-defense or affirmatively approved by the Security Council. Though many of their operations have followed these rules, the United States and NATO have been accused of committing crimes against peace in international law, for example in the 1999 Yugoslavia and 2003 Iraq operations.

Aid

The U.S. provides military aid through many different channels. Counting the items that appear in the budget as 'Foreign Military Financing' and 'Plan Colombia', the U.S. spent approximately $4.5 billion in military aid in 2001, of which $2 billion went to Israel, $1.3 billion went to Egypt, and $1 billion went to Colombia.[41] Since 9/11, Pakistan has received approximately $11.5 billion in direct military aid.[42]

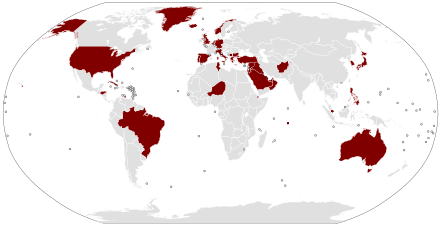

As of 2004, according to Fox News, the U.S. had more than 700 military bases in 130 different countries.[43]

Estimated U.S. foreign military financing and aid by recipient for 2010:

| Recipient | Military aid 2010 (USD Billions) |

|---|---|

| 6.50 | |

| 5.60[44] | |

| 2.75[45] | |

| 1.75[46] | |

| 1.60[47] | |

| .834[48] | |

| .300[49] | |

| .100[46] | |

| .070 |

According to a 2016 report by the Congressional Research Service, the U.S. topped the market in global weapon sales for 2015, with $40 billion sold. The largest buyers were Qatar, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Pakistan, Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Iraq.[50]

Missile defense

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was a proposal by U.S. President Ronald Reagan on March 23, 1983[51] to use ground and space-based systems to protect the United States from attack by strategic nuclear ballistic missiles,[52] later dubbed "Star Wars".[53] The initiative focused on strategic defense rather than the prior strategic offense doctrine of mutual assured destruction (MAD). Though it was never fully developed or deployed, the research and technologies of SDI paved the way for some anti-ballistic missile systems of today.[54]

In February 2007, the U.S. started formal negotiations with Poland and Czech Republic concerning construction of missile shield installations in those countries for a Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system[55] (in April 2007, 57% of Poles opposed the plan).[56] According to press reports the government of the Czech Republic agreed (while 67% Czechs disagree)[57] to host a missile defense radar on its territory while a base of missile interceptors is supposed to be built in Poland.[58][59]

Russia threatened to place short-range nuclear missiles on the Russia's border with NATO if the United States refuses to abandon plans to deploy 10 interceptor missiles and a radar in Poland and the Czech Republic.[60][61] In April 2007, Putin warned of a new Cold War if the Americans deployed the shield in Central Europe.[62] Putin also said that Russia is prepared to abandon its obligations under an Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty of 1987 with the United States.[63]

On August 14, 2008, the United States and Poland announced a deal to implement the missile defense system in Polish territory, with a tracking system placed in the Czech Republic.[64] "The fact that this was signed in a period of very difficult crisis in the relations between Russia and the United States over the situation in Georgia shows that, of course, the missile defense system will be deployed not against Iran but against the strategic potential of Russia", Dmitry Rogozin, Russia's NATO envoy, said.[55][65]

Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, argue in Foreign Affairs that U.S. missile defenses are designed to secure Washington's nuclear primacy and are chiefly directed at potential rivals, such as Russia and China. The authors note that Washington continues to eschew nuclear first strike and contend that deploying missile defenses "would be valuable primarily in an offensive context, not a defensive one; as an adjunct to a US First Strike capability, not as a stand-alone shield":

If the United States launched a nuclear attack against Russia (or China), the targeted country would be left with only a tiny surviving arsenal, if any at all. At that point, even a relatively modest or inefficient missile defense system might well be enough to protect against any retaliatory strikes.[66]

This analysis is corroborated by the Pentagon's 1992 Defense Planning Guidance (DPG), prepared by then Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney and his deputies. The DPG declares that the United States should use its power to "prevent the reemergence of a new rival" either on former Soviet territory or elsewhere. The authors of the Guidance determined that the United States had to "Field a missile defense system as a shield against accidental missile launches or limited missile strikes by 'international outlaws'" and also must "Find ways to integrate the 'new democracies' of the former Soviet bloc into the U.S.-led system". The National Archive notes that Document 10 of the DPG includes wording about "disarming capabilities to destroy" which is followed by several blacked out words. "This suggests that some of the heavily excised pages in the still-classified DPG drafts may include some discussion of preventive action against threatening nuclear and other WMD programs."[67]

Finally, Robert David English, writing in Foreign Affairs, observes that in addition to the deployment U.S. missile defenses, the DPG's second recommendation has also been proceeding on course. "Washington has pursued policies that have ignored Russian interests (and sometimes international law as well) in order to encircle Moscow with military alliances and trade blocs conducive to U.S. interests."[68]

Exporting democracy

Studies have been devoted to the historical success rate of the U.S. in exporting democracy abroad. Some studies of American intervention have been pessimistic about the overall effectiveness of U.S. efforts to encourage democracy in foreign nations.[69] Until recently, scholars have generally agreed with international relations professor Abraham Lowenthal that U.S. attempts to export democracy have been "negligible, often counterproductive, and only occasionally positive".[70][71] Other studies find U.S. intervention has had mixed results,[69] and another by Hermann and Kegley has found that military interventions have improved democracy in other countries.[72]

Opinion that U.S. intervention does not export democracy

In United States history, critics have charged that presidents have used democracy to justify military intervention abroad.[73][74] Critics have also charged that the U.S. helped local militaries overthrow democratically elected governments in Iran, Guatemala, and in other instances.

Professor Paul W. Drake argued that the U.S. first attempted to export democracy in Latin America through intervention from 1912 to 1932. Drake argued that this was contradictory because international law defines intervention as "dictatorial interference in the affairs of another state for the purpose of altering the condition of things". The study suggested that efforts to promote democracy failed because democracy needs to develop out of internal conditions, and can not be forcibly imposed. There was disagreement about what constituted democracy; Drake suggested American leaders sometimes defined democracy in a narrow sense of a nation having elections; Drake suggested a broader understanding was needed. Further, there was disagreement about what constituted a "rebellion"; Drake saw a pattern in which the U.S. State Department disapproved of any type of rebellion, even so-called "revolutions", and in some instances rebellions against dictatorships.[75] Historian Walter LaFeber stated, "The world's leading revolutionary nation (the U.S.) in the eighteenth century became the leading protector of the status quo in the twentieth century."[76]

.jpg)

Mesquita and Downs evaluated 35 U.S. interventions from 1945 to 2004 and concluded that in only one case, Colombia, did a "full fledged, stable democracy" develop within ten years following the intervention.[77][78] Samia Amin Pei argued that nation building in developed countries usually unravelled four to six years after American intervention ended. Pei, based on study of a database on worldwide democracies called Polity, agreed with Mesquita and Downs that U.S. intervention efforts usually don't produce real democracies, and that most cases result in greater authoritarianism after ten years.[79]

Professor Joshua Muravchik argued U.S. occupation was critical for Axis power democratization after World War II, but America's failure to encourage democracy in the third world "prove ... that U.S. military occupation is not a sufficient condition to make a country democratic".[80][81] The success of democracy in former Axis countries such as Italy were seen as a result of high national per-capita income, although U.S. protection was seen as a key to stabilization and important for encouraging the transition to democracy. Steven Krasner agreed that there was a link between wealth and democracy; when per-capita incomes of $6,000 were achieved in a democracy, there was little chance of that country ever reverting to an autocracy, according to an analysis of his research in the Los Angeles Times.[82]

Opinion that U.S. intervention has mixed results

Tures examined 228 cases of American intervention from 1973 to 2005, using Freedom House data. A plurality of interventions, 96, caused no change in the country's democracy. In 69 instances, the country became less democratic after the intervention. In the remaining 63 cases, a country became more democratic.[69] However this does not take into account the direction the country would have gone with no U.S. intervention.

Opinion that U.S. intervention effectively exports democracy

Hermann and Kegley found that American military interventions designed to protect or promote democracy increased freedom in those countries.[72] Peceny argued that the democracies created after military intervention are still closer to an autocracy than a democracy, quoting Przeworski "while some democracies are more democratic than others, unless offices are contested, no regime should be considered democratic."[83] Therefore, Peceny concludes, it is difficult to know from the Hermann and Kegley study whether U.S. intervention has only produced less repressive autocratic governments or genuine democracies.[84]

Peceny stated that the United States attempted to export democracy in 33 of its 93 20th-century military interventions.[85] Peceny argued that proliberal policies after military intervention had a positive impact on democracy.[86]

Global opinion

A global survey done by Pewglobal indicated that at (as of 2014) least 33 surveyed countries have a positive view (50% or above) of the United States. With the top ten most positive countries being Philippines (92%), Israel (84%), South Korea (82%), Kenya (80%), El Salvador (80%), Italy (78%), Ghana (77%), Vietnam (76%), Bangladesh (76%), and Tanzania (75%). While 10 surveyed countries have the most negative view (Below 50%) of the United States. With the countries being Egypt (10%), Jordan (12%), Pakistan (14%), Turkey (19%), Russia (23%), Palestinian Territories (30%), Greece (34%), Argentina (36%), Lebanon (41%), Tunisia (42%). Americans' own view of the United States was viewed at 84%.[87] International opinion about the US has often changed with different executive administrations. For example, in 2009, the French public favored the United States when President Barack Obama (75% favorable) replaced President George W. Bush (42%). After President Donald Trump took the helm in 2017, French public opinion about the US fell from 63% to 46%. These trends were also seen in other European countries.[88]

Covert actions

United States foreign policy also includes covert actions to topple foreign governments that have been opposed to the United States. According to J. Dana Stuster, writing in Foreign Policy, there are seven "confirmed cases" where the U.S.—acting principally through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), but sometimes with the support of other parts of the U.S. government, including the Navy and State Department—covertly assisted in the overthrow of a foreign government: Iran in 1953, Guatemala in 1954, Congo in 1960, the Dominican Republic in 1961, South Vietnam in 1963, Brazil in 1964, and Chile in 1973. Stuster states that this list excludes "U.S.-supported insurgencies and failed assassination attempts" such as those directed against Cuba's Fidel Castro, as well as instances where U.S. involvement has been alleged but not proven (such as Syria in 1949).[89]

In 1953 the CIA, working with the British government, initiated Operation Ajax against the Prime Minister of Iran Mohammad Mossadegh who had attempted to nationalize Iran's oil, threatening the interests of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. This had the effect of restoring and strengthening the authoritarian monarchical reign of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[90] In 1957, the CIA and Israeli Mossad aided the Iranian government in establishing its intelligence service, SAVAK, later blamed for the torture and execution of the regime's opponents.[91][92]

A year later, in Operation PBSuccess, the CIA assisted the local military in toppling the democratically elected left-wing government of Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala and installing the military dictator Carlos Castillo Armas. The United Fruit Company lobbied for Árbenz overthrow as his land reforms jeopardized their land holdings in Guatemala, and painted these reforms as a communist threat. The coup triggered a decades long civil war which claimed the lives of an estimated 200,000 people (42,275 individual cases have been documented), mostly through 626 massacres against the Maya population perpetrated by the U.S.-backed Guatemalan military.[93][95][96] An independent Historical Clarification Commission found that U.S. corporations and government officials "exercised pressure to maintain the country's archaic and unjust socio-economic structure," and that U.S. military assistance had a "significant bearing on human rights violations during the armed confrontation".[97]

During the massacre of at least 500,000 alleged communists in 1960s Indonesia, U.S. government officials encouraged and applauded the mass killings while providing covert assistance to the Indonesian military which helped facilitate them.[98][99][100][101][102] This included the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta supplying Indonesian forces with lists of up to 5,000 names of suspected members of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), who were subsequently killed in the massacres.[103][104][105][106] In 2001, the CIA attempted to prevent the publication of the State Department volume Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, which documents the U.S. role in providing covert assistance to the Indonesian military for the express purpose of the extirpation of the PKI.[102][107][108] In July 2016, an international panel of judges ruled the killings constitute crimes against humanity, and that the US, along with other Western governments, were complicit in these crimes.[109]

In 1970, the CIA worked with coup-plotters in Chile in the attempted kidnapping of General René Schneider, who was targeted for refusing to participate in a military coup upon the election of Salvador Allende. Schneider was shot in the botched attempt and died three days later. The CIA later paid the group $35,000 for the failed kidnapping.[110][111]

Influencing foreign elections

According to one peer-reviewed study, the U.S. intervened in 81 foreign elections between 1946 and 2000, while the Soviet Union or Russia intervened in 36.[112][113]

Human rights

Since the 1970s, issues of human rights have become increasingly important in American foreign policy.[114] Congress took the lead in the 1970s.[115] Following the Vietnam War, the feeling that U.S. foreign policy had grown apart from traditional American values was seized upon by Senator Donald M. Fraser (D, MI), leading the Subcommittee on International Organizations and Movements, in criticizing Republican Foreign Policy under the Nixon administration. In the early 1970s, Congress concluded the Vietnam War and passed the War Powers Act. As "part of a growing assertiveness by Congress about many aspects of Foreign Policy,"[116] Human Rights concerns became a battleground between the Legislative and the Executive branches in the formulation of foreign policy. David Forsythe points to three specific, early examples of Congress interjecting its own thoughts on foreign policy:

- Subsection (a) of the International Financial Assistance Act of 1977: ensured assistance through international financial institutions would be limited to countries "other than those whose governments engage in a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights".[116]

- Section 116 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended in 1984: reads in part, "No assistance may be provided under this part to the government of any country which engages in a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights."[116]

- Section 502B of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended in 1978: "No security assistance may be provided to any country the government of which engages in a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights."[116]

These measures were repeatedly used by Congress, with varying success, to affect U.S. foreign policy towards the inclusion of Human Rights concerns. Specific examples include El Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala and South Africa. The Executive (from Nixon to Reagan) argued that the Cold War required placing regional security in favor of U.S. interests over any behavioral concerns of national allies. Congress argued the opposite, in favor of distancing the United States from oppressive regimes.[115] Nevertheless, according to historian Daniel Goldhagen, during the last two decades of the Cold War, the number of American client states practicing mass murder outnumbered those of the Soviet Union.[118] John Henry Coatsworth, a historian of Latin America and the provost of Columbia University, suggests the number of repression victims in Latin America alone far surpassed that of the USSR and its East European satellites during the period 1960 to 1990.[119] W. John Green contends that the United States was an "essential enabler" of "Latin America's political murder habit, bringing out and allowing to flourish some of the region's worst tendencies".[120]

On December 6, 2011, Obama instructed agencies to consider LGBT rights when issuing financial aid to foreign countries.[121] He also criticized Russia's law discriminating against gays,[122] joining other western leaders in the boycott of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Russia.[123]

In June 2014, a Chilean court ruled that the United States played a key role in the murders of Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi, both American citizens, shortly after the 1973 Chilean coup d'état.[124]

War on Drugs

United States foreign policy is influenced by the efforts of the U.S. government to control imports of illicit drugs, including cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, and cannabis. This is especially true in Latin America, a focus for the U.S. War on Drugs. Those efforts date back to at least 1880, when the U.S. and China completed an agreement that prohibited the shipment of opium between the two countries.

Over a century later, the Foreign Relations Authorization Act requires the President to identify the major drug transit or major illicit drug-producing countries. In September 2005,[125] the following countries were identified: Bahamas, Bolivia, Brazil, Burma, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti, India, Jamaica, Laos, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Venezuela. Two of these, Burma and Venezuela are countries that the U.S. considers to have failed to adhere to their obligations under international counternarcotics agreements during the previous 12 months. Notably absent from the 2005 list were Afghanistan, the People's Republic of China and Vietnam; Canada was also omitted in spite of evidence that criminal groups there are increasingly involved in the production of MDMA destined for the United States and that large-scale cross-border trafficking of Canadian-grown cannabis continues. The U.S. believes that the Netherlands are successfully countering the production and flow of MDMA to the U.S.

Criticism

Critics from the left cite episodes that undercut leftist governments or showed support for Israel. Others cite human rights abuses and violations of international law. Critics have charged that the U.S. presidents have used democracy to justify military intervention abroad.[73][74] Critics also point to declassified records which indicate that the CIA under Allen Dulles and the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover aggressively recruited more than 1,000 Nazis, including those responsible for war crimes, to use as spies and informants against the Soviet Union in the Cold War.[126][127]

The U.S. has faced criticism for backing right-wing dictators that systematically violated human rights, such as Augusto Pinochet of Chile,[128] Alfredo Stroessner of Paraguay,[129] Efraín Ríos Montt of Guatemala,[130] Jorge Rafael Videla of Argentina,[131] Hissène Habré of Chad[132][133] Yahya Khan of Pakistan[134] and Suharto of Indonesia.[101][105] Critics have also accused the United States of facilitating and supporting state terrorism in the Global South during the Cold War, such as Operation Condor, an international campaign of political assassination and state terror organized by right-wing military dictatorships in the Southern Cone of South America.[135][136][129][137]

Journalists and human rights organizations have been critical of US-led airstrikes and targeted killings by drones which have in some cases resulted in collateral damage of civilian populations.[138][139] In early 2017, the U.S. faced criticism from some scholars, activists and media outlets for dropping 26,171 bombs on seven different countries throughout 2016: Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan.[140][141][142] The U.S. has been accused of complicity in war crimes for backing the Saudi Arabian-led intervention into the Yemeni Civil War (2015–present), which has triggered a humanitarian catastrophe, including a cholera outbreak and millions facing starvation.[143][144][145]

Studies have been devoted to the historical success rate of the U.S. in exporting democracy abroad. Some studies of American intervention have been pessimistic about the overall effectiveness of U.S. efforts to encourage democracy in foreign nations.[69] Some scholars have generally agreed with international relations professor Abraham Lowenthal that U.S. attempts to export democracy have been "negligible, often counterproductive, and only occasionally positive".[70][71] Other studies find U.S. intervention has had mixed results,[69] and another by Hermann and Kegley has found that military interventions have improved democracy in other countries.[72] A 2013 global poll in 68 countries with 66,000 respondents by Win/Gallup found that the U.S. is perceived as the biggest threat to world peace.[146][147][148]

Support

Regarding support for certain anti-Communist dictatorships during the Cold War, a response is that they were seen as a necessary evil, with the alternatives even worse Communist or fundamentalist dictatorships. David Schmitz says this policy did not serve U.S. interests. Friendly tyrants resisted necessary reforms and destroyed the political center (though not in South Korea), while the 'realist' policy of coddling dictators brought a backlash among foreign populations with long memories.[149][150]

Many democracies have voluntary military ties with United States. See NATO, ANZUS, Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, Mutual Defense Treaty with South Korea, and Major non-NATO ally. Those nations with military alliances with the U.S. can spend less on the military since they can count on U.S. protection. This may give a false impression that the U.S. is less peaceful than those nations.[151][152]

Research on the democratic peace theory has generally found that democracies, including the United States, have not made war on one another. There have been U.S. support for coups against some democracies, but for example Spencer R. Weart argues that part of the explanation was the perception, correct or not, that these states were turning into Communist dictatorships. Also important was the role of rarely transparent United States government agencies, who sometimes mislead or did not fully implement the decisions of elected civilian leaders.[153]

Empirical studies (see democide) have found that democracies, including the United States, have killed much fewer civilians than dictatorships.[154][155] Media may be biased against the U.S. regarding reporting human rights violations. Studies have found that The New York Times coverage of worldwide human rights violations predominantly focuses on the human rights violations in nations where there is clear U.S. involvement, while having relatively little coverage of the human rights violations in other nations.[156][157] For example, the bloodiest war in recent time, involving eight nations and killing millions of civilians, was the Second Congo War, which was almost completely ignored by the media.

Niall Ferguson argues that the U.S. is incorrectly blamed for all the human rights violations in nations they have supported. He writes that it is generally agreed that Guatemala was the worst of the US-backed regimes during the Cold War. However, the U.S. cannot credibly be blamed for all the 200,000 deaths during the long Guatemalan Civil War.[150] The U.S. Intelligence Oversight Board writes that military aid was cut for long periods because of such violations, that the U.S. helped stop a coup in 1993, and that efforts were made to improve the conduct of the security services.[158]

Today the U.S. states that democratic nations best support U.S. national interests. According to the U.S. State Department, "Democracy is the one national interest that helps to secure all the others. Democratically governed nations are more likely to secure the peace, deter aggression, expand open markets, promote economic development, protect American citizens, combat international terrorism and crime, uphold human and worker rights, avoid humanitarian crises and refugee flows, improve the global environment, and protect human health."[159] According to former U.S. President Bill Clinton, "Ultimately, the best strategy to ensure our security and to build a durable peace is to support the advance of democracy elsewhere. Democracies don't attack each other."[160] In one view mentioned by the U.S. State Department, democracy is also good for business. Countries that embrace political reforms are also more likely to pursue economic reforms that improve the productivity of businesses. Accordingly, since the mid-1980s, under President Ronald Reagan, there has been an increase in levels of foreign direct investment going to emerging market democracies relative to countries that have not undertaken political reforms.[161] Leaked cables in 2010 suggested that the "dark shadow of terrorism still dominates the United States' relations with the world".[162]

The United States officially maintains that it supports democracy and human rights through several tools [163] Examples of these tools are as follows:

- A published yearly report by the State Department entitled "Advancing Freedom and Democracy",[164] issued in compliance with ADVANCE Democracy Act of 2007 (earlier the report was known as "Supporting Human Rights and Democracy: The U.S. Record" and was issued in compliance with a 2002 law).[165]

- A yearly published "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices".[166]

- In 2006 (under President George W. Bush), the United States created a "Human Rights Defenders Fund" and "Freedom Awards".[167]

- The "Human Rights and Democracy Achievement Award" recognizes the exceptional achievement of officers of foreign affairs agencies posted abroad.[168]

- The "Ambassadorial Roundtable Series", created in 2006, are informal discussions between newly confirmed U.S. Ambassadors and human rights and democracy non-governmental organizations.[169]

- The National Endowment for Democracy, a private non-profit created by Congress in 1983 (and signed into law by President Ronald Reagan), which is mostly funded by the U.S. Government and gives cash grants to strengthen democratic institutions around the world.

See also

- International relations, 1648–1814

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- International relations (1919–1939)

- American entry into World War I

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- Diplomatic history of World War II

- Cold War

- United States foreign policy in the Middle East

- United States and state terrorism

- United States and state-sponsored terrorism

Constitutional and international law

References

- "Alphabetical List of Bureaus and Offices". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- "Bureau of Budget and Planning". State.gov. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- "About the Committee". Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- James M. McCormick, American Foreign Policy and Process (2009) ch. 7–8

- George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (2008)

- Richard Russell, "American Diplomatic Realism: A Tradition Practised and Preached by George F. Kennan," Diplomacy and Statecraft, Nov 2000, Vol. 11 Issue 3, pp. 159–83

- Oren, Michael B. (November 3, 2005). "The Middle East and the Making of the United States, 1776 to 1815".

- Arthur S. Link and William M. Leary Jr. "Election of 1916: 'He Kept Us out of War'." in Arthur M, Schlesinger, Jr., ed., The Coming to Power: Critical Elections in American History (1971): 296-321.

- Donald L. Miller (2015). Supreme City: How Jazz Age Manhattan Gave Birth to Modern America. Simon and Schuster. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9781416550204.

- Seymour Martin Lipset, "Neoconservatism: Myth and reality." Society 25.5 (1988): pp. 9-13 online.

- Colin Dueck, Hard Line: The Republican Party and U.S. Foreign Policy since World War II (2010).

- Nikolas K. Gvosdev (January 2, 2008). "FDR's Children". National Interest. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

Hachigian ... and Sutphen ... recognize that the global balance of power is changing; that despite America's continued predominance, the other pivotal powers "do challenge American dominance and impinge on the freedom of action the U.S. has come to enjoy and expect". Rather than focusing on the negatives, however, they believe that these six powers have the same vested interests: All are dependent on the free flow of goods around the world and all require global stability in order to ensure continued economic growth (and the prosperity it engenders).

- See Peter Baker, "Tips for Leaders Meeting Trump: Keep It Short and Give Him a Win," New York Times May 18, 2017

- Aaron David Miller and Richard Sokolsky, "Should Rex Tillerson Resign?," Politico October 1, 2017

- Laurence H. Tribe, "Taking Text and Structure Seriously: Reflections on Free-Form Method in Constitutional Interpretation," 108 Harv. L. Rev. 1221, 1227 (1995).

- The power of the League was limited by the United States' refusal to join.Northedge, F.S (1986). The League of Nations: Its Life and Times, 1920–1946. Holmes & Meier. pp. 276–78. ISBN 0-7185-1316-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The United States was responsible for 36% of greenhouse gas emissions at the time of the Kyoto Protocol

- The United States Should Ratify The Law Of The Sea Convention (due to China citing U.S. citing non-ratification as a reason it doesn't need to follow the agreement)

- "Why won't America ratify the UN convention on children's rights?". The Economist. October 6, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- Hufbauer, Gary Clyde; Schott, Jeffrey J. (1994). Western Hemisphere Economic Integration. Peterson Institute. pp. 132–22. ISBN 9780881321593.

- John Pike. "Gates Delivers Keynote Address to Open Asia Security Conference". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- Shanker, Tom. "Gates Talks of Boosting Asian Security Despite Budget Cuts." New York Times, 1 June 2011.

- "United States - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". Eia.gov. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- "Company Level Imports". Eia.doe.gov. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- Bush Leverage With Russia, Iran, China Falls as Oil Prices Rise, Bloomberg.com

- Shrinking Our Presence in Saudi Arabia, New York Times

- The End of Cheap Oil, National Geographic

- James Paul. "Crude Designs". Global Policy Forum. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- The war is about oil but it's not that simple, NBC News

- "The United States Navy and the Persian Gulf". Archived from the original on January 1, 2015.

- What if the Chinese were to apply the Carter Doctrine?, Haaretz - Israel News

- Selling the Carter Doctrine, TIME

- Alan Greenspan claims Iraq war was really for oil, Times Online

- Oil giants to sign contracts with Iraq, The Guardian

- See Energy Information Administration, "Canada" (2009 report) Archived December 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- See "FY 2014 Omnibus – State and Foreign Operations Appropriations" (Jan 2014)

- "We're sorry, that page can't be found" (PDF). fpc.state.gov. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- Stanford University Press. "The Politics of American Foreign Policy: How Ideology Divides Liberals and Conservatives over Foreign Affairs - Peter Hays Gries". Sup.org. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- "U.S. Collective Defense Arrangements". State.gov. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- "U.S. Policy in Colombia | Amnesty International USA". Amnestyusa.org. Archived from the original on October 22, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- "The News International: Latest, Breaking, Pakistan, Sports and Video News". Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- Fox News, 1 November 2004 Analysts Ponder U.S. Basing in Iraq

- "Afghanistan: US foreign assistance" (PDF). Fas.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- "Page Not Found". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- Anne Davies (January 2, 2010). "US aid tied to purchase of arms". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- "Aid to Pakistan" (PDF). Belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- "U.S. Arms and Training Fuel UAE's War in Yemen" (PDF). Ciponline.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- "Jordan: Background and U.S relations" (PDF). Fas.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- "U.S. Sold $40 Billion in Weapons in 2015, Topping Global Market". The New York Times. December 26, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- Federation of American Scientists. Missile Defense Milestones Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed March 10, 2006.

- Johann Hari: Obama's chance to end the fantasy that is Star Wars, The Independent, November 13, 2008

- Historical Documents: Reagan's 'Star Wars' speech Archived December 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, CNN Cold War

- "Son of "Star Wars" - How Missile Defense Systems Will Work". HowStuffWorks. April 5, 2001. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- "Missile defense backers now cite Russia threat". News.yahoo.com. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- U.S. Might Negotiate on Missile Defense, washingtonpost.com

- Citizens on U.S. Anti-Missile Radar Base in Czech Republic Archived November 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Europe diary: Missile defence, BBC News

- "Missile Defense: Avoiding a Crisis in Europe". rand.org. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- Russia piles pressure on EU over missile shield, Telegraph

- China, Russia sign nuclear deal, condemn U.S. missile defense plans, International Herald Tribune

- Russia threatening new cold war over missile defence, The Guardian

- U.S., Russia no closer on missile defense, USATODAY.com

- Russia Lashes Out on Missile Deal, The New York Times, August 15, 2008

- Russia angry over U.S. missile shield, Al Jazeera English, August 15, 2008

- "The Rise of U.S. Nuclear Primacy" Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, Foreign Affairs, March/April 2006

- "Prevent the Reemergence of a New Rival" The National Security Archive

- "Russia, Trump, and a New Détente" Foreign Affairs, March 10, 2017

- Tures, John A. "Operation Exporting Freedom: The Quest for Democratization via United States Military Operations" (PDF). Whitehead Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations.PDF file.

- Lowenthal, Abraham (1991). The United States and Latin American Democracy: Learning from History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 243–65.

- Peceny, Mark (1999). Democracy at the Point of Bayonets. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 183. ISBN 0-271-01883-6.

- Hermann, Margaret G.; Kegley, Charles (1998). "The U.S. Use of Military Intervention to Promote Democracy: Evaluating the Record". International Interactions. 24 (2): 91–114. doi:10.1080/03050629808434922.

- Mesquita, Bruce Bueno de (Spring 2004). "Why Gun-Barrel Democracy Doesn't Work". Hoover Digest. 2. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Also see this page.

- Meernik, James (1996). "United States Military Intervention and the Promotion of Democracy". Journal of Peace Research. 33 (4): 391–402. doi:10.1177/0022343396033004002.

- Lowenthal, Abraham F. (March 1, 1991). Exporting Democracy : The United States and Latin America. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1, 4, 5. ISBN 0-8018-4132-1.

- Lafeber, Walter (1993). Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30964-9.

- Factors included limits on executive power, clear rules for the transition of power, universal adult suffrage, and competitive elections.

- "Why Gun-Barrel Democracy Doesn't Work". Hoover Institution. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- Pei, Samia Amin (March 17, 2004). "Why Nation-Building Fails in Mid-Course". International Herald Tribune.

- Peceny, p. 186.

- Muravchik, Joshua (1991). Exporting Democracy: Fulfilling America's Destiny. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute Press. pp. 91–118. ISBN 0-8447-3734-8.

- Krasner, Stephen D. (November 26, 2003). "We Don't Know How To Build Democracy". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- Przeworski, Adam; Przeworski, Adam; Limongi Neto, Fernando Papaterra; Alvarez, Michael M. (1996). "What Makes Democracy Endure". Journal of Democracy. 7 (1): 39–55. doi:10.1353/jod.1996.0016. S2CID 153323245.

- Peceny, p. 193

- Peceny, p. 2

- Review: Shifter, Michael; Peceny, Mark (Winter 2001). "Democracy at the Point of Bayonets". Latin American Politics and Society. 43 (4): 150. doi:10.2307/3177036. JSTOR 3177036.

- "Global Indicators Database". Pewglobal.org. April 22, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- "5 trends in international public opinion from our searchable Global Indicators Database".

- Stuster, J. Dana (August 20, 2013). "Mapped: The 7 Governments the U.S. Has Overthrown". Foreign Policy. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- "Special Report: Secret History of the CIA in Iran". The New York Times. 2000.

- Curtis, Glenn E.; Hooglund, Eric, eds. (2008). Iran: A Country Study (Fifth ed.). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, Federal Research Division. p. 276. ISBN 9780844411873.

- "Timeline: A Modern History of Iran". PBS NewsHour. February 11, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- Stephen Schlesinger (3 June 2011). Ghosts of Guatemala's Past. The New York Times. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Jones, Maggie (June 30, 2016). "The Secrets in Guatemala's Bones". The New York Times. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Cooper, Allan (2008). The Geography of Genocide. University Press of America. p. 171. ISBN 978-0761840978.

- Blakeley, Ruth (2009). State Terrorism and Neoliberalism: The North in the South. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-0415686174.

- Robinson, Geoffrey B. (2018). The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965-66. Princeton University Press. pp. 22–23, 177. ISBN 9781400888863.

- Beech, Hannah (October 18, 2017). "U.S. Stood by as Indonesia Killed a Half-Million People, Papers Show". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- Simpson, Bradley (2010). Economists with Guns: Authoritarian Development and U.S.–Indonesian Relations, 1960-1968. Stanford University Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0804771825.

Washington did everything in its power to encourage and facilitate the army-led massacre of alleged PKI members, and U.S. officials worried only that the killing of the party's unarmed supporters might not go far enough, permitting Sukarno to return to power and frustrate the [Johnson] Administration's emerging plans for a post-Sukarno Indonesia.

- Kai Thaler (December 2, 2015). 50 years ago today, American diplomats endorsed mass killings in Indonesia. Here's what that means for today. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- Margaret Scott (November 2, 2015) The Indonesian Massacre: What Did the US Know? The New York Review of Books. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- Robinson, Geoffrey B. (2018). The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965-66. Princeton University Press. p. 203. ISBN 9781400888863.

a US Embassy official in Jakarta, Robert Martens, had supplied the Indonesian Army with lists containing the names of thousands of PKI officials in the months after the alleged coup attempt. According to the journalist Kathy Kadane, "As many as 5,000 names were furnished over a period of months to the Army there, and the Americans later checked off the names of those who had been killed or captured." Despite Martens later denials of any such intent, these actions almost certainly aided in the death or detention of many innocent people. They also sent a powerful message that the US government agreed with and supported the army's campaign against the PKI, even as that campaign took its terrible toll in human lives.

- Bellamy, Alex J. (2012). Massacres and Morality: Mass Atrocities in an Age of Civilian Immunity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-928842-9. p. 210.

- Mark Aarons (2007). "Justice Betrayed: Post-1945 Responses to Genocide." In David A. Blumenthal and Timothy L. H. McCormack (eds). The Legacy of Nuremberg: Civilising Influence or Institutionalised Vengeance? (International Humanitarian Law). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9004156917 pp. 80–81

- Valentino, Benjamin A. (2005). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century. Cornell University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0801472732.

- U.S. Seeks to Keep Lid on Far East Purge Role. The Associated Press via The Los Angeles Times, July 28, 2001. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- Thomas Blanton (ed). CIA Stalling State Department Histories: State Historians Conclude U.S. Passed Names Of Communists To Indonesian Army, Which Killed At Least 105,000 In 1965–66. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 52., July 27, 2001. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- Perry, Juliet (July 21, 2016). "Tribunal finds Indonesia guilty of 1965 genocide; US, UK complicit". CNN. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- CIA Admits Involvement in Chile. ABC News. September 20

- John Dinges. The Condor Years: How Pinochet And His Allies Brought Terrorism To Three Continents. The New Press, 2005. p. 20. ISBN 1565849779

- Levin, Dov H. (June 2016). "When the Great Power Gets a Vote: The Effects of Great Power Electoral Interventions on Election Results". International Studies Quarterly. 60 (2): 189–202. doi:10.1093/isq/sqv016. See the full list of interventions in the appendix. Archived January 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Agrawal, Nina (December 21, 2016). "The U.S. is no stranger to interfering in the elections of other countries". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- Joe Renouard, Human Rights in American Foreign Policy: From the 1960s to the Soviet Collapse (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2016). 324 pp.

- Crabb, Cecil V.; Pat Holt (1992). Invitation to Struggle: Congress, the President and Foreign Policy (2nd ed.). Michigan: Congressional Quarterly. pp. 187–211. ISBN 978-0-87187-622-5.

- Forsythe, David (1988). Human Rights and U.S. Foreign Policy: Congress Reconsidered. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-0-8130-0885-1.

Human Rights and U.S. Foreign Policy: Congress Reconsidered.

- "Saudi Arabia: President Obama must not shirk responsibility to tackle human rights during visit". Amnesty International. March 28, 2014.

- Daniel Goldhagen (2009). Worse Than War. PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-769-8 p. 537

- "During the 1970s and 1980s, the number of American client states practicing mass-murderous politics exceeded those of the Soviets."

- Coatsworth, John Henry (2012). "The Cold War in Central America, 1975–1991". In Leffler, Melvyn P.; Westad, Odd Arne (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Cold War (Volume 3). Cambridge University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-1107602311.

- W. John Green (June 1, 2015). A History of Political Murder in Latin America: Killing the Messengers of Change Archived March 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. SUNY Press. p. 147. ISBN 1438456638

- McVeigh, Karen (December 6, 2011). "Gay rights must be criterion for U.S. aid allocations, instructs Obama". The Guardian. London. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- Adomanis, Mark (December 19, 2013). "Barack Obama Is Right To Promote Gay Rights In Russia, Now He Should Be Consistent". Forbes. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- Bershidsky, Leonid (December 19, 2013). "Putin Plays Games to Salvage Olympics". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- Pascale Bonnefoy (30 June 2014). Chilean Court Rules U.S. Had Role in Murders. The New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "Memorandum for the Secretary of State". Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. September 15, 2005. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- Eric Lichtblau (October 26, 2014). In Cold War, U.S. Spy Agencies Used 1,000 Nazis. The New York Times. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- The Nazis Next Door: Eric Lichtblau on How the CIA & FBI Secretly Sheltered Nazi War Criminals. Democracy Now! October 31, 2014.

- Peter Kornbluh (September 11, 2013). The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability. The New Press. ISBN 1595589120 p. xviii

- Walter L. Hixson (2009). The Myth of American Diplomacy: National Identity and U.S. Foreign Policy. Yale University Press. p. 223. ISBN 0300151314

- What Guilt Does the U.S. Bear in Guatemala? The New York Times, May 19, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- Duncan Campbell (December 5, 2003). Kissinger approved Argentinian 'dirty war'. The Guardian. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- Hissène Habré, Ex-President of Chad, Is Convicted of War Crimes. The New York Times. May 30, 2016.

- From U.S. Ally to Convicted War Criminal: Inside Chad's Hissène Habré's Close Ties to Reagan Admin. Democracy Now! May 31, 2016.

- Looking Away from Genocide. The New Yorker. November 19, 2013.

- Blakeley, Ruth (2009). State Terrorism and Neoliberalism: The North in the South. Routledge. p. 22 & 23. ISBN 978-0415686174.

- McSherry, J. Patrice (2011). "Chapter 5: "Industrial repression" and Operation Condor in Latin America". In Esparza, Marcia; Henry R. Huttenbach; Daniel Feierstein (eds.). State Violence and Genocide in Latin America: The Cold War Years (Critical Terrorism Studies). Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-0415664578.

Operation Condor also had the covert support of the US government. Washington provided Condor with military intelligence and training, financial assistance, advanced computers, sophisticated tracking technology, and access to the continental telecommunications system housed in the Panama Canal Zone.

- Greg Grandin (2011). The Last Colonial Massacre: Latin America in the Cold War. University of Chicago Press. p. 75. ISBN 9780226306902

- U.S.-led airstrikes in Syria kill civilians, rights groups say. CNN. July 20, 2016.

- Jeremy Scahill and the staff of The Intercept (2016). The Assassination Complex: Inside the Government's Secret Drone Warfare Program. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781501144134

- Grandin, Greg (January 15, 2017). "Why Did the US Drop 26,171 Bombs on the World Last Year?". The Nation. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Agerholm, Harriet (January 19, 2017). "Map shows where President Barack Obama dropped his 20,000 bombs". The Independent. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Benjamin, Medea (January 9, 2017). "America dropped 26,171 bombs in 2016. What a bloody end to Obama's reign". The Guardian. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Warren Strobel, Jonathan Landay (August 5, 2018). "Exclusive: As Saudis bombed Yemen, U.S. worried about legal blowback". Reuters.

- Emmons, Alex (14 November 2017). "Chris Murphy Accuses the U.S. of Complicity in War Crimes from the Floor of the Senate". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "PBS Report from Yemen: As Millions Face Starvation, American-Made Bombs Are Killing Civilians". Democracy Now!. July 19, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- Goodenough, Patrick. "And The Country Posing The Greatest Threat to Peace as 2013 Ends is …". CNS News. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- "US the biggest threat to world peace in 2013 – poll". Rt.com. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- Editorial, Post (January 5, 2014). "US is the greatest threat to world peace: poll | New York Post". Nypost.com. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- The United States and Right-Wing Dictatorships, 1965–1989. David F. Schmitz. 2006.

- Do the sums, then compare U.S. and Communist crimes from the Cold War Telegraph, 11 December 2005, Niall Ferguson

- Give peace a rating May 31, 2007, from The Economist print edition

- Japan ranked as world's 5th most peaceful nation: report Japan Today, May 31, 2007

- Weart, Spencer R. (1998). Never at War. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07017-9. pp. 221–24, 314.

- Death By Government By R.J. Rummel New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1994. Online links: