Lincoln Highway

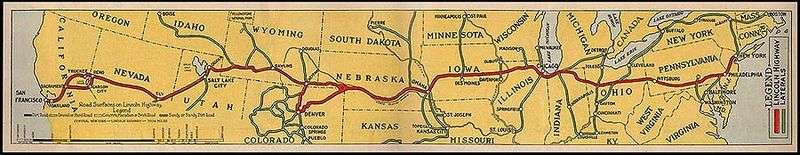

The Lincoln Highway is one of the earliest transcontinental highway routes for automobiles across the United States of America.[1] Conceived in 1912 by Indiana entrepreneur Carl G. Fisher, and formally dedicated October 31, 1913, the Lincoln Highway ran coast-to-coast from Times Square in New York City west to Lincoln Park in San Francisco, originally through 13 states: New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California. In 1915, the "Colorado Loop" was removed, and in 1928, a realignment relocated the Lincoln Highway through the northern tip of West Virginia. Thus, there are a total of 14 states, 128 counties, and more than 700 cities, towns and villages through which the highway passed at some time in its history.

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Route information | |

| Length | 3,389 mi (5,454 km) |

| Existed | 1913–present |

| Major junctions | |

| West end | Lincoln Park in San Francisco, CA |

| East end | Times Square in New York, NY |

| Location | |

| States | California, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York |

| Highway system | |

| Auto trails | |

The first officially recorded length of the entire Lincoln Highway in 1913 was 3,389 miles (5,454 km).[lower-alpha 1] Over the years, the road was improved and numerous realignments were made,[3] and by 1924 the highway had been shortened to 3,142 miles (5,057 km). Counting the original route and all of the subsequent realignments, there have been a grand total of 5,872 miles (9,450 km).[4]

The Lincoln Highway was gradually replaced with numbered designations after the establishment of the U.S. Numbered Highway System in 1926, with most of the route becoming part of U.S. Route 30 from Pennsylvania to Wyoming. After the Interstate Highway System was formed in the 1950s, the former alignments of the Lincoln Highway were largely superseded by Interstate 80 as the primary coast-to-coast route from the New York City area to San Francisco.

1928–30 routing

Note: A fully interactive online map of the entire Lincoln Highway and all of its re-alignments, markers, monuments and points of interest can be viewed at the Lincoln Highway Association Official Map website.[5] Google Maps prominently labels the 1928–30 route.

Most of U.S. Route 30 from Philadelphia to western Wyoming, portions of Interstate 80 in the western United States, most of U.S. Route 50 in Nevada and California, and most of old decommissioned U.S. Route 40 in California are alignments of the Lincoln Highway. The final (1928–1930) alignment of the Lincoln Highway corresponds roughly to the following roads:

- 42nd Street from the intersection of Broadway at Times Square in New York City westward 6 blocks to the Hudson River.

- Holland Tunnel from New York City westward under the Hudson River to Jersey City, New Jersey.

(Note: The Lincoln Tunnel (opened in 1937), near 42nd Street, was not an original part of the Lincoln Highway. In 1913, Lincoln Highway travelers crossed the Hudson River via the Weehawken Ferry from New York City to Union City, New Jersey. In 1928, the Lincoln Highway was re-routed through the Holland Tunnel (opened in 1927) from New York City to Jersey City. However, the original Lincoln Highway Association made no attempt to map a route from Times Square to the Holland Tunnel, so today, use the West Side Highway (not a part of the Lincoln Highway) to connect from the west end of 42nd Street down to east portal of the Holland Tunnel.) - U.S. Route 1/9 Truck from Jersey City westward to Newark, New Jersey.

- New Jersey Route 27 from Newark southwestward to Princeton, New Jersey.

- U.S. Route 206 from Princeton southwestward to Trenton, New Jersey.

- U.S. Route 1 from Trenton southwestward to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- U.S. Route 30 from Philadelphia westward across Pennsylvania, the northern tip of West Virginia, and westward across Ohio and Indiana, to Aurora, Illinois.

(Note: There have been many new 4-lane bypasses constructed on U.S. Route 30, so to follow the 1928 route of the Lincoln Highway, at times it is necessary to travel the old U.S. Route 30 alignments through the center of the cities and towns along the route.) - Illinois Route 31 from Aurora northwestward to Geneva, Illinois.

- Illinois Route 38 from Geneva westward to Dixon, Illinois.

- Illinois Route 2 from Dixon westward to Sterling, Illinois.

- U.S. Route 30 from Sterling westward across western Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska and Wyoming, to Granger, Wyoming.

- Interstate 80 from Granger westward across western Wyoming and Utah, to West Wendover, Nevada.

- U.S. Route 93 Alternate and U.S. Route 93 from West Wendover southward to Ely, Nevada.

- U.S. Route 50 (aka “The Loneliest Road in America”) from Ely westward across Nevada, to 9 miles west of Fallon, Nevada.

- From 9 miles west of Fallon to Sacramento, California, there are two Lincoln Highway routes over the Sierra Nevada:

- Sierra Nevada Northern Route: U.S. Route 50 Alternate northwestward to Wadsworth, Nevada, then Interstate 80 & old U.S. Route 40 westward, through Reno, Nevada, and over Donner Pass and the Sierra Nevada to Sacramento.

- Sierra Nevada Southern Route: U.S. Route 50 westward, through Carson City, Nevada, then around Lake Tahoe and over Johnson Pass (nearby Echo Summit) and the Sierra Nevada to Sacramento.

- Old U.S. Route 40 (with sections under Interstate 80) from Sacramento southwestward across California's Central Valley to the University Avenue exit in Berkeley, California.

(Note: Originally this leg of the Lincoln Highway followed what would later become U.S. Route 50, from Sacramento south through Stockton and over the Altamont Pass to the East Bay (now Interstates 5, 205, and 580), but was realigned when the Carquinez Bridge was completed in 1927.) - University Avenue from Interstate 80 westward to the Berkeley Pier.

(Note: In 1928, Lincoln Highway travelers crossed the San Francisco Bay via a ferry from the Berkeley Pier to the Hyde Street Pier in San Francisco. Today, use Interstate 80 to connect from University Avenue down to the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge (opened in 1936) to cross the bay into San Francisco, then take the Embarcadero from the Bay Bridge northwestward along the waterfront to connect to the Hyde Street Pier in Fisherman's Wharf.) - From the Hyde Street Pier in San Francisco, take:

- Hyde Street southward 2 blocks to North Point Street.

- North Point Street westward 3 blocks to Van Ness Avenue.

- Van Ness Avenue southward 16 blocks to California Street.

- California Street westward 54 blocks to 32nd Avenue.

- 32nd Avenue northward 2 blocks to Camino del Mar

- Camino del Mar westward into Lincoln Park, arriving at the Lincoln Highway Western Terminus Plaza and Fountain in front of the California Palace of the Legion of Honor. The Western Terminus Marker and Interpretive Plaque are located to the left of the Palace, next to the bus stop.

History

The Lincoln Highway was America's first national memorial to President Abraham Lincoln, predating the 1922 dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., by nine years. As the first automobile road across America, the Lincoln Highway brought great prosperity to the hundreds of cities, towns and villages along the way. The Lincoln Highway became affectionately known as "The Main Street Across America".[6]

The Lincoln Highway was inspired by the Good Roads Movement. In turn, the success of the Lincoln Highway and the resulting economic boost to the governments, businesses and citizens along its route inspired the creation of many other named long-distance roads (known as National Auto Trails), such as the Yellowstone Trail, National Old Trails Road, Dixie Highway, Jefferson Highway, Bankhead Highway, Jackson Highway, Meridian Highway and Victory Highway. Many of these named highways were supplanted by the United States Numbered Highways system of 1926. Most of the 1928 Lincoln Highway route became U.S. Route 30 (US 30), with portions becoming US 1 in the East and US 40, US 50 and US 93 in the West. Since 1928, many sections of US 30 have been re-aligned with new bypasses; therefore, today's US 30 aligns with less than 25% of the original 1913–28 Lincoln Highway routes.

Most significantly, the Lincoln Highway inspired the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, also known as the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act (Public Law 84-627), which was championed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, influenced by his experiences as a young soldier crossing the country in the 1919 Army Convoy on the Lincoln Highway. Today, Interstate 80 (I-80) is the cross-country highway most closely aligned with the Lincoln Highway. In the West, particularly in Wyoming, Utah and California, sections of I-80 are paved directly over old alignments of the Lincoln Highway.

The Lincoln Highway Association, originally established in 1913 to plan, promote, and sign the highway, was re-formed in 1992 and is now dedicated to promoting and preserving the road.

Concept and promotion

In 1912, railroads dominated interstate transportation in America, and roadways were primarily of local interest. Outside cities, "market roads" were sometimes maintained by counties or townships, but maintenance of rural roads fell to those who lived along them. Many states had constitutional prohibitions against funding "internal improvements" such as road projects, and federal highway programs were not to become effective until 1921.

At the time, the country had about 2.2 million miles (3.5×106 km) of rural roads, of which a mere 8.66% (190,476 miles or 306,541 kilometres) had "improved" surfaces: gravel, stone, sand-clay, brick, shells, oiled earth, etc. Interstate roads were considered a luxury, something only for wealthy travelers who could spend weeks riding around in their automobiles.

Support for a system of improved interstate highways had been growing. For example, in 1911, Champ Clark, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, wrote, "I believe the time has come for the general Government to actively and powerfully co-operate with the States in building a great system of public highways ... that would bring its benefits to every citizen in the country".[7] However, Congress as a whole was not yet ready to commit funding to such projects.

Carl G. Fisher was an early automobile entrepreneur who was the manufacturer of Prest-O-Lite carbide-gas headlights used on most early cars, and was also one of the principal investors who built the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. He believed that the popularity of automobiles was dependent on good roads. In 1912 he began promoting his dream of a transcontinental highway, and at a September 10 dinner meeting with industry friends in Indianapolis, he called for a coast-to-coast rock highway to be completed by May 1, 1915, in time for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.[8] He estimated the cost at about $10 million and told the group, "Let's build it before we're too old to enjoy it!"[1] Within a month Fisher's friends had pledged $1 million. Henry Ford, the biggest automaker of his day, refused to contribute because he believed the government should build America's roads. However, contributors included former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt and Thomas A. Edison, both friends of Fisher, as well as then-current President Woodrow Wilson, the first U.S. President to make frequent use of an automobile for relaxation.

Fisher and his associates chose a name for the road, naming it after one of Fisher's heroes, Abraham Lincoln. At first they had to consider other names,[9] such as "The Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway" or "The Ocean-to-Ocean Highway," because the Lincoln Highway name had been reserved earlier by a group of Easterners who were seeking support to build their Lincoln Highway from Washington to Gettysburg on federal funds. When Congress turned down their proposed appropriation, the project collapsed, and Fisher's preferred name became readily available.

On July 1, 1913, the Lincoln Highway Association (LHA) was established "to procure the establishment of a continuous improved highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific, open to lawful traffic of all description without toll charges".[1] The first goal of the LHA was to build the rock highway from Times Square in New York City to Lincoln Park in San Francisco. The second goal was to promote the Lincoln Highway as an example to, in Fisher's words, "stimulate as nothing else could the building of enduring highways everywhere that will not only be a credit to the American people but that will also mean much to American agriculture and American commerce".[1] Henry Joy was named as the LHA president, so that although Carl Fisher remained a driving force in furthering the goals of the association, it would not appear as his one-man crusade.[9]

The first section of the Lincoln Highway to be completed and dedicated was the Essex and Hudson Lincoln Highway, running along the former Newark Plank Road from Newark, New Jersey, to Jersey City, New Jersey. It was dedicated on December 13, 1913[10] at the request of the Associated Automobile Clubs of New Jersey and the Newark Motor Club, and was named after the two counties it passed through.[11][12]

Lincoln statues

To bring attention to the highway, Fisher commissioned statues of Abraham Lincoln, titled The Great Emancipator, to be placed in key locations along the route of the highway. One of the statues was given to Joy in 1914.[13] Joy's statue was later presented to the Detroit Area Council of the Boy Scouts of America. That statue is currently on display at D-bar-A Scout Ranch in Metamora, Michigan.[14] There is another statue of Lincoln in the main entrance of Lincoln Park (Jersey City).

Route selection and dedication

The LHA needed to determine the best and most direct route from New York City to San Francisco. East of the Mississippi River, route selection was eased by the relatively dense road network. To scout a western route, the LHA's "Trail-Blazer" tour set out from Indianapolis in 17 cars and two trucks on July 1, 1913, the same day LHA headquarters were established in Detroit. After 34 days of Iowa mud pits, sand drifts in Nevada and Utah, overheated radiators, flooded roads, cracked axles, and enthusiastic greetings in every town that thought it had a chance of being on the new highway, the tour arrived for a parade down San Francisco's Market Street before thousands of cheering residents.

The Trail-Blazers returned to Indianapolis by train, and a few weeks later on September 14, 1913, the route was announced. LHA leaders, particularly Packard president Henry Joy, wanted as straight a route as possible and the 3,389-mile (5,454 km) route announced did not necessarily follow the course of the Trail-Blazers. There were many disappointed town officials, particularly in Colorado and Kansas, who had greeted the Trail-Blazers and thought the tour's passage had meant their towns would be on the Highway.

Less than half the selected route was improved roadway. As segments were improved over time, the route length was reduced by about 250 miles (400 km). Several segments of the Lincoln Highway route followed historic roads:

- a road laid out by Dutch colonists of New Jersey before 1675

- the 1796 Lancaster Turnpike in Pennsylvania

- the Chambersburg Turnpike, over which much of the Army of Northern Virginia marched to reach the Gettysburg Battlefield, a part of which is traversed by the Lincoln Highway.

- a British military trail built in 1758 by General John Forbes of England from Chambersburg to Pittsburgh during the French and Indian War, later known as the Pittsburgh Road and the Conestoga Road

- a section in Ohio followed an ancient Indian trail known as the Ridge Road

- sections of the Mormon Trail

- the Great Sauk Trail, an Indian trail through northwest Indiana

- portions of the routes of the Cherokee Trail, Overland Trail and the Pony Express

- the Donner Pass crossing of the Sierra Nevada, named after the unfortunate Donner Party of 1846

- an alternate Sierra Nevada crossing at Echo Summit following a pioneer stagecoach route

The LHA dedicated the route on October 31, 1913. Bonfires, fireworks, concerts, parades, and street dances were held in hundreds of cities in the 13 states along the route. During a dedication ceremony in Iowa, State Engineer Thomas H. MacDonald said he felt it was "... the first outlet for the road building energies of this community".[1] He went on to advocate the creation of a system of transcontinental highways with radial routes. In 1919, MacDonald became Commissioner of the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR), a post he held until 1953, when he oversaw the early stages of the Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways.

Publicity

In September 1912, in a letter to a friend, Fisher wrote that "... the highways of America are built chiefly of politics, whereas the proper material is crushed rock, or concrete".[1] The leaders of the LHA were masters of the public relations, and used publicity and propaganda as even more important materials.

In the early days of the effort, each contribution from a famous supporter was publicized. Theodore Roosevelt and Thomas Edison, both friends of Fisher, sent checks. A friendly Member of the United States Congress arranged for a dedicated motor enthusiast, President Woodrow Wilson, to contribute $5 whereupon he was issued Highway Certificate #1. Copies of the certificate were promptly distributed to the press.

One of the best-known contributions came from a small group of Native Alaskan children in Anvik, Alaska. Their American teacher told them about Abraham Lincoln and the highway to be built in his honor, and they took up a collection and sent it to the LHA with the note, "Fourteen pennies from Anvik Esquimaux children for the Lincoln Highway".[1] The LHA distributed pictures of the coins and the accompanying letter, and both were widely reprinted.

One of Fisher's first acts after opening LHA headquarters was to hire F. T. Grenell, city editor of the Detroit Free Press, as a part-time publicity man. The Trail-Blazer tour included representatives of the Hearst newspaper syndicate, the Indianapolis Star and News, the Chicago Tribune, and telegraph companies to help transmit their dispatches.

In preparation for the October 31 dedication ceremonies, the LHA asked clergy across the United States to discuss Abraham Lincoln in their sermons on November 2, the Sunday nearest the dedication. The LHA then distributed copies of many of the sermons, such as one by Cardinal James Gibbons who, with the dedication fresh in mind, had written that "such a highway will be a most fitting and useful monument to the memory of Lincoln".[1]

One of the greater contributions to highway development was a well-publicized and promoted United States Army Transcontinental Motor Convoy in 1919. The convoy left the White House in Washington, D.C., on July 7, 1919, and met the Lincoln Highway route at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. After two months of travel, the convoy reached San Francisco on September 6, 1919. Though bridges failed, vehicles broke and were sometimes stuck in mud, the convoy was greeted in communities across the country. The LHA used the convoy's difficulties to show the need for better main highways, building popular support for both local and federal funding. The convoy led to the passage of many county bond issues supporting highway construction.

One of the participants in the convoy was Lieutenant Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower, and it was so memorable that he devoted a chapter to it ("Through Darkest America With Truck and Tank") in his 1967 book At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends. That 1919 experience, and his exposure to the autobahn network in Germany in the 1940s, found expression in 1954 when he announced his "Grand Plan" for highways. The resulting Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 created the Highway Trust Fund that accelerated construction of the Interstate Highway System.

Fisher's idea that the auto industry and private contributions could pay for the highway was soon abandoned, and, while the LHA did help finance a few short sections of roadway, LHA founders' and members' contributions were used primarily for publicity and promotion to encourage travel on the Highway and to lobby officials at all levels to support its construction by governments.

Early travel

According to the Association's 1916 Official Road Guide a trip from the Atlantic to the Pacific on the Lincoln Highway was "something of a sporting proposition" and might take 20 to 30 days.[1] To make it in 30 days the motorist would need to average 18 miles (29 km) an hour for 6 hours per day, and driving was only done during daylight hours. The trip was thought to cost no more than $5 a day per person, including food, gas, oil, and even "five or six meals in hotels". Car repairs would, of course, increase the cost.

Since gasoline stations were still rare in many parts of the country, motorists were urged to top off their gasoline at every opportunity, even if they had done so recently. Motorists should wade through water before driving through to verify the depth. The list of recommended equipment included chains, a shovel, axe, jacks, tire casings and inner tubes, tools, and (of course) a pair of Lincoln Highway pennants. And, the guide offered this sage advice: "Don't wear new shoes".[1]

Firearms were not necessary, but west of Omaha full camping equipment was recommended, and the guide warned against drinking alkali water that could cause serious cramps. In certain areas, advice was offered on getting help, for example near Fish Springs, Utah, "If trouble is experienced, build a sagebrush fire. Mr. Thomas will come with a team. He can see you 20 miles off".[1] Later editions omitted Mr. Thomas, but westbound travelers were advised to stop at the Orr's Ranch for advice, and eastbound motorists were to check with Mr. K.C. Davis of Gold Hill, Nevada.

Seedling miles and the ideal section

The Lincoln Highway Association did not have enough funds to sponsor large sections of the road, but from 1914 it did sponsor "seedling mile" projects. According to the 1924 LHA Guide the seedling miles were intended "to demonstrate the desirability of this permanent type of road construction" to rally public support for government-backed construction. The LHA convinced industry of their self-interest and was able to arrange donations of materials from the Portland Cement Association.[1]

The first seedling mile (1.6 km) was built in 1914 west of Malta, Illinois; but, after years of experience, the LHA organized a design plan for a road section that could handle traffic 20 years into the future. Seventeen highway experts met between December 1920 and February 1921, and specified:

- a right-of-way 110 feet (34 m) in width

- a concrete road bed 40 feet (12 m) wide and 10 inches (254 mm) thick to support loads of 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) per wheel

- curves with a minimum radius of 1,000 feet (300 m), banked for 35 mph (56 km/h), with guard rails at embankments

- no grade crossings or advertising signs

- a footpath for pedestrians[1]

The most famous seedling mile built to these specifications was the 1.3-mile (2.1 km) "ideal section" between Dyer and Schererville in Lake County, Indiana. With federal, state, and county funds, and a $130,000 contribution by United States Rubber Company president and LHA founder C.B. Seger, the ideal section was built during 1922 and 1923. Magazines and newspapers called the ideal section a vision of the future, and highway officials from across the country visited and wrote technical papers that circulated both in the United States and overseas. The ideal section is still in use to this day, and has worn so well that a driver would not notice it unless the marker near the road brought it to their attention.[1]

United States Numbered Highways

By the mid-1920s there were about 250 national auto trails. Some were major routes, such as the Lincoln Highway, the Jefferson Highway, the National Old Trails Road, the Old Spanish Trail, and the Yellowstone Trail, but most were shorter. Some of the shorter routes were formed more to generate revenues for a trail association rather than for their value as a route between significant locations.

By 1925 governments had joined the roadbuilding movement, and began to assert control. Federal and state officials established the Joint Board on Interstate Highways, which proposed a numbered U.S. Highway System which would make the trail designations obsolete, though technically the Joint Board had no authority over highway names. Increasing government support for roadbuilding was making the old road associations less important, but the LHA still had significant influence. The Secretary of the Joint Board, BPR official E. W. James, went to Detroit to gain LHA support for the numbering scheme, knowing it would be hard for smaller road associations to object if the LHA publicly supported the new plan.

The LHA preferred numbering the existing named routes, but in the end the LHA was more interested in the larger plan for roadbuilding than they were in officially retaining the name. They knew the Lincoln Highway name was fixed in the mind of the public, and James promised them that, so far as possible, the Lincoln Highway would have the number 30 for its entire route. An editorial in the February 1926 issue of The Lincoln Forum reflected the outcome:

The Lincoln Highway Association would have liked to have seen the Lincoln Highway designated as a United States route entirely across the continent and designated by a single numeral throughout its length. But it realized that this was only a sentimental consideration. ... The Lincoln Way is too firmly established upon the map of the United States and in the minds and hearts of the people as a great, useful and everlasting memorial to Abraham Lincoln to warrant any skepticism as to the attitude of those States crossed by the route. Those universally familiar red, white and blue markers, in many states the first to be erected on any thru route, will never lose their significance or their place on America's first transcontinental road.

The states approved the new national numbering system in November 1926 and began putting up new signs. The Lincoln Highway was not alone in being split among several numbers, but the entire routing between Philadelphia and Granger, Wyoming, was assigned US 30 per the agreement. East of Philadelphia the Lincoln Highway was part of US 1, and west of Salt Lake City the route became US 40 across Donner Pass. Only the segment between Granger and Salt Lake City was not part of the new numbering plan; US 30 was assigned to a more northerly route toward Pocatello, Idaho. When US 50 was extended to California it followed the Lincoln Highway's alternate route south of Lake Tahoe.

The last major promotional activity of the LHA took place on September 1, 1928, when at 1:00 p.m. groups of Boy Scouts placed approximately 2,400 concrete markers at sites along the route to officially mark and dedicate it to the memory of Abraham Lincoln. Less commonly known is that 4,000 metal signs for urban areas were also erected then.[lower-alpha 2] The markers were placed on the outer edge of the right of way at major and minor crossroads, and at reassuring intervals along uninterrupted segments. Each concrete post carried the Lincoln Highway insignia and directional arrow, as well as a bronze medallion with Lincoln's bust stating, "This Highway Dedicated to Abraham Lincoln".[1]

The Lincoln Highway was not yet the imagined "rock highway" from coast to coast when the LHA ceased operating, as there were many segments that had still not been paved. Some parts were because of reroutings, such as a dispute in the early 1920s with Utah officials that forced the LHA to change routes in western Utah and eastern Nevada. Construction was underway on the final unpaved 42-mile (68 km) segment by the 25th anniversary of the Lincoln Highway in 1938.

25th anniversary

On June 8, 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1938, which called for a BPR report on the feasibility of a system of transcontinental toll roads. The "Toll Roads and Free Roads" report was the first official step toward creation of the Interstate Highway System in the United States.

The 25th Anniversary of the Lincoln Highway was noted a month later in a July 3, 1938, nationwide radio broadcast on NBC Radio. The program featured interviews with a number of LHA officials, and a message from Carl Fisher read by an announcer in Detroit. Fisher's statement included:

The Lincoln Highway Association has accomplished its primary purpose, that of providing an object lesson to show the possibility in highway transportation and the importance of a unified, safe, and economical system of roads. ... Now I believe the country is at the beginning of another new era in highway building (that will) create a system of roads far beyond the dreams of the Lincoln Highway founders. I hope this anniversary observance makes millions of people realize how vital roads are to our national welfare, to economic programs, and to our national defense ...

Since 1940

Fisher died about a year after the 25th Anniversary in 1939, having lost most of his fortune as a result of the great hurricane that slammed Miami beach in 1928, followed by the Great Depression at the same time that he was pouring millions of dollars into his Montauk Long Island resort development.

On June 29, 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, authorizing the construction of the Interstate Highway System. The New York-to-San Francisco transcontinental route in the system, Interstate 80, would however largely follow a different path across the country than US 30. I-80 would also not be signed all the way to the New York City, instead terminating in Teaneck, New Jersey, west of the Hudson River just a few miles short of the George Washington Bridge.

In the many years since, the Lincoln Highway has remained a persistent memory:

- In New Jersey, parts of US 1/9 and New Jersey Route 27 still carry the name.

- Some segments of US 30 still carry the name.

- Some city streets on which the Lincoln Highway was routed still carry the street name Lincoln Way or Lincolnway including: South Bend, Indiana; Mishawaka, Indiana; Massillon, Ohio; Lisbon, Ohio;Valparaiso, Indiana; Aurora, Illinois; DeKalb, Illinois; Ames, Iowa; Cheyenne, Wyoming; Sparks, Nevada; Auburn, California; and Galt, California.[lower-alpha 3]

- Old Lincoln Highway is a secondary street in Trevose, Pennsylvania, using the old highway alignment. As well as Old Lincoln Highway in Fairless Hills, Pennsylvania, Business Route 1 in Lower Bucks County that runs from Morrisville to Penndel, Pennsylvania where it connects with Route 1 Super Highway where the Lincoln Highway got cut off because of the Highway system being built.

- A few of the 3,000 Boy Scout markers can be found along the old route. In some communities, these are being re-established in cooperation with the LHA, such as West Sacramento and Davis, California.

- A stretch near Omaha, Nebraska, paved with original brick has been preserved by the city government.

- A bridge with railings spelling out "Lincoln Highway" remains in use as part of County Road E66 in Tama County, Iowa.

- Restaurants, motels, and gas stations in many locations still carry Lincoln-related names.

- Near Wamsutter, Wyoming, on what was then thought to be the Continental Divide along old US 30, a monument was erected in 1938 to Henry B. Joy, the first president of the LHA, with an inscription describing Joy as one "who saw realized the dream of a continuous improved highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific." Not far from the memorial along I-80 a motorist could see an abandoned stretch of the Lincoln Highway with weeds growing through cracks in the pavement. In 2001, this monument was relocated to a place on I-80 midway between Cheyenne and Laramie.

- At the rest area off exit 323 of I-80 east of Laramie is Sherman Summit, the highest point on all of I-80. Located there is a thirteen and a half foot bronze bust of Lincoln. It is mounted on a massive, thirty-five foot granite base. The monument was created in 1959 to mark the high point of the Lincoln Highway and it originally stood about half a mile west and 200 feet (61 m) higher along US 30 which closely followed the path of the Lincoln Highway across this summit. It was moved to the present location in 1969 after I-80 was opened. Robert Russin, an art professor at the University of Wyoming created this stern, brooding sculpture. It was cast in 30 pieces in the favorable climate of Mexico City and assembled in Wyoming. The base is hollow and has ladders and lightning rods inside.

- Will County, Illinois, has four schools named after the highway: Lincoln-Way Central High School in New Lenox, Lincoln-Way East High School in Frankfort, Lincoln-Way West High School in New Lenox, and Lincoln-Way North High School in Frankfort. All schools are members of Lincoln-Way Community High School District 210.

Historic recognition

| State | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Iowa | Lincoln Highway Bridge (Tama, Iowa) | |

| West Greene County Rural Segment, near Scranton, Iowa | These segments in Greene County are described in a Multiple Property Submission.[17] | |

| Raccoon River Rural Segment, near Jefferson, Iowa | ||

| Two highway markers in Jefferson, Iowa 42°0′56″N 94°21′59″W | ||

| Buttrick's Creek Abandoned Segment 42°1′2″N 94°16′57″W | ||

| Buttrick's Creek to Grand Junction | ||

| Grand Junction Segment, in Grand Junction, Iowa | ||

| West Beaver Creek Abandoned Segment 42°1′59″N 94°12′49″W | ||

| Little Beaver Creek Bridge 42°2′57″N 94°10′37″W | ||

| Nebraska | A segment from Omaha to Elkhorn | |

| A segment in Elkhorn 41°17′0″N 96°11′45″W | ||

| Gardiner Station 41°21′40″N 97°33′30″W | ||

| Duncan West 41°23′31″N 97°29′14″W

Blair, Nebraska 41°32′44″N 96°8′4″W | ||

| Utah | Lincoln Highway Bridge (Dugway Proving Ground, Utah) 40°10′58.43″N 112°55′26.68″W |

Revitalized Lincoln Highway Association

The Lincoln Highway Association was re-formed in 1992 with the mission, "... to identify, preserve, and improve access to the remaining portions of the Lincoln Highway and its associated historic sites".[1] The new LHA publishes a quarterly magazine, The Lincoln Highway Forum, and holds conferences each year in cities along the route. Its 1000 members are located across the U.S. and eight other countries. There are active state chapters in 12 Lincoln Highway states and a national tourist center in Franklin Grove, Illinois, in a historic building built by Harry Isaac Lincoln, a cousin of Abraham Lincoln. The LHA holds yearly national conferences and is governed by a board of directors with representatives from each Lincoln Highway state.[18]

21st century tours

In 2003, the Lincoln Highway Association sponsored the 90th Anniversary Tour of the entire road, from Times Square in New York City to Lincoln Park in San Francisco. The tour group, led by Bob Lichty and Rosemary Rubin of LHA and sponsored by Lincoln-Mercury division of the Ford Motor Company, set out from Times Square on August 17, 2003. Approximately 35 vintage and modern vehicles, including several new Lincoln Town Cars and Lincoln Navigators from Lincoln-Mercury, traveled about 225 miles (360 km) per day and attempted to cover as many of the original Lincoln Highway alignments as possible. The group was met by LHA chapters, car clubs, local tourism groups and community leaders throughout the route. Several Boy Scout troops along the way held ceremonies to commemorate the 75th Anniversary of the nationwide LH route marker post erection of September 1, 1928. When the tour concluded at Lincoln Park, in front of the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, another ceremony was held to honor both the 90th Anniversary of the road and the 75th anniversary of the post erections.

In 2013, the Lincoln Highway Association hosted a tour commemorating the highway's 100th anniversary.[19] Over 270 people traveling in 140 vehicles, from 28 states and from Australia, Canada, England, Germany, Norway and Russia, participated in the two tours which started simultaneously the last week of June 2013 in New York City and San Francisco, and took one week to reach the midpoint of the Lincoln Highway in Kearney, Nebraska. The tour cars, both historical and modern, spanned 100 years, from 1913 to 2013, and included two of Henry B. Joy's original Lincoln Highway Packards, as well as a 1948 Tucker (car #8). On June 30, 2013, the Centennial Parade in downtown Kearney featuring the tour cars plus another 250 vehicles was attended by 12,500 people. The next day, on July 1, 2013, the Centennial Celebration Gala was hosted at the Great Platte River Road Archway Museum, where a proclamation from the United States Senate was presented to the Lincoln Highway Association.

An independent international motor tour also toured the highway from July 1–26. Seventy-one classic cars were shipped from Europe to the United States and driven the entire route before being shipped home.[20]

In 2015, the Lincoln Highway Association hosted a tour celebrating the 100th anniversary of the famed 1915 tour led by Henry B. Joy, president of the original Lincoln Highway Association, from Detroit to the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.[21] Joy was president of the Packard Motor Car Company. Both the Packard Club (Packard Automobile Classics) and the Packards International Motor Car Club participated in the planning of the tour.[22][23] The 2015 tour, with 103 people in 55 cars, took 12 days and traveled 2,836 miles (4,564 km) from the Packard Proving Grounds north of Detroit to the Lincoln Highway Western Terminus in Lincoln Park in San Francisco.

Mapping

In 2012, the 25-member Lincoln Highway Association National Mapping Committee, chaired by Paul Gilger, completed the research and cartography of the entire Lincoln Highway and all its subsequent realignments (totaling 5,872 mi or 9,450 km), a project which took more than 20 years. The association's interactive map website (https://www.lincolnhighwayassoc.org) includes map, terrain, satellite and street-level views of the entire Lincoln Highway and all of its re-alignments, markers, monuments and historic points of interest.

Roadside giants

During early Lincoln Highway days, business owners were intrigued with all the automobiles traveling the Lincoln Highway. In an effort to capture the business of these new motorists, some entrepreneurs created larger-than-life buildings in quirky shapes. Structures like Bedford's 2 1⁄2-story coffee pot, or the Shoe House near York, Pennsylvania, are examples of the "Roadside Giants" of the Lincoln Highway.[24]

In 2008, the Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor secured funding from the Sprout Fund in Pittsburgh for a new kind of Roadside Giants of the Lincoln Highway. High school boys and girls enrolled in five different career and technology schools along the 200-mile (320 km) Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor were invited to create their own Giant that would be permanently installed along the old Lincoln. The project involved collaboration among the schools' graphic arts, welding, building trades, and culinary arts departments. A structural engineer was hired to provide professional guidance to the design and installation of the Giants.[24] They include:

- A 12-foot-high (3.7 m) 1920s Packard Car and Driver

- A 25-foot-high (7.6 m), 4,900-pound (2,200 kg) replica of a 1940s Bennett Gas Pump

- The 1,800-pound (820 kg) "Bicycle Built for Two"

- The oversized quarter, weighing almost a ton

- A detailed 1921 Selden pick-up truck

- The world's largest teapot, 12 feet (3.7 m) tall and 44 feet (13 m) wide

Medicine

The carotid sheath, a layer of connective tissue, was called the "Lincoln Highway of the Neck" by Harris B. Mosher in his 1929 address to the American Academy of Otology, because of its role in the spread of infections.[25]

Media

Literature

In 1914, Effie Gladding wrote Across the Continent by the Lincoln Highway about her travel adventures on the road with her husband Thomas. Subsequently, Gladding wrote the foreword to the Lincoln Highway Association's first road guide, directing it to women motorists. Her 1914 book was the first full-size hardback book to discuss transcontinental travel, as well as the first to mention the Lincoln Highway:

We were now to traverse the Lincoln Highway and were to be guided by the red, white, and blue marks: sometimes painted on telephone poles; sometimes put up by way of advertisement over garage doors or swinging on hotel signboards; sometimes painted on little stakes, like croquet goals, scattered along over the great spaces of the desert. We learned to love the red, white, and blue, and the familiar big L which told us that we were on the right road.[26]

In 1916, "Mistress of Etiquette" Emily Post was commissioned by Collier's magazine to cross the United States on the Lincoln Highway and write about it. Her son Edwin drove, and an unnamed family member joined them. Her story was published as a book, By Motor to the Golden Gate. Her fame came later in 1922, with the publication of her first etiquette book.

In 1919, author Beatrice Massey, who was a passenger as her husband drove, travelled across the country on the Lincoln Highway. When they reached Salt Lake City, Utah, instead of taking the rough and desolate Lincoln Highway around the south end of the Salt Lake Desert, they took the even more rough and more desolate "non-Lincoln" route around the north end of the Great Salt Lake. The arduousness of that section of the trip was instrumental in the Masseys deciding to ditch their road trip in Montello, Nevada (northeast of Wells, Nevada) where they paid $196.69 to ship their automobile and themselves by train the rest of the way to California. Nevertheless, an enthusiastic Beatrice Massey wrote in her 1919 travelogue It Might Have Been Worse:

You will get tired, and your bones will cry aloud for a rest cure; but I promise you one thing—you will never be bored! No two days were the same, no two views were similar, no two cups of coffee tasted alike ... My advice to timid motorists is, "Go".[27]

In 1927, humorist Frederic Van de Water wrote The Family Flivvers to Frisco, an autobiographical account of him and his wife, a young couple from New York City, piling their belongings and their six-year-old son into their Model T Ford and camping their way to San Francisco on the Lincoln Highway, traveling over 4,500 miles (7,200 km) through 12 states in 37 days. In his book, not much is made of the burden of traveling with a child who has a mind of his own. When they were forced by passing cars into a ditch near DeKalb, Illinois, Van de Water writes that his son ("a small irate figure in yellow oilskins"), "scrambled over the door and started to walk in the general direction of New York". The Van de Waters' travel expenses for their entire trip amounted to $247.83.

In 1951, Clinton Twiss authored the famous and funny memoir The Long, Long Trailer, about his adventures living in a trailer and traveling across America with his wife Merle. Many of their episodes occurred on the Lincoln Highway, including almost losing their brakes coming down off Donner Pass, barely squeezing across the narrow Lyons-Fulton Bridge over the Mississippi River, and getting stopped at the Holland Tunnel because trailers weren't allowed through. Twiss's book became the basis for the popular 1954 MGM film of the same name, directed by Vincente Minnelli, and starring Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball. Although no filming occurred on the Lincoln Highway, early in the movie, Desi, who finds Lucy's suggestion of living in a trailer ridiculous, jokes: "The Collinis at home! Please drop in for cocktails! You'll find us someplace along the Lincoln Highway!"

In April 1988, the University of Iowa Press published Lincoln Highway, the Main Street Across America, a text-and-photo essay and history by Drake Hokanson.[28] Hokanson had been intrigued by the mystery of this once-famous highway, and tried to explain the fascination with the route in an August 1985 article in Smithsonian magazine:

If it had been restlessness and desire for a better way across the continent that brought the Lincoln Highway into existence, it was curiosity that kept it alive—the notion that the point of traveling was not just to cover the distance but to savor the texture of life along the way. Maybe we've lost that, but the opportunity to rediscover it is still out there waiting for us anytime we feel like turning off an exit ramp.[29]

From 1995 through 2009, author and historian Gregory Franzwa (1926–2009) wrote a state-by-state series of books about the Lincoln Highway. Franzwa completed seven books: The Lincoln Highway: Iowa (1995), The Lincoln Highway: Nebraska (1996), The Lincoln Highway: Wyoming (1999), The Lincoln Highway: Utah (with Jesse G. Petersen, 2003), The Lincoln Highway: Nevada (with Jesse G. Petersen, 2004), The Lincoln Highway: California (2006), and The Lincoln Highway: Illinois (2009). The books were published by the Patrice Press. Each state book contains both detailed history and USGS level maps showing the various Lincoln Highway alignments. Franzwa served as the first president of the revitalized Lincoln Highway Association, in 1992.

In 2002, British author Pete Davies wrote American Road: The Story of an Epic Transcontinental Journey at the Dawn of the Motor Age, about the 1919 Army Convoy on the Lincoln Highway. About the book, Publishers Weekly said:

In his newest book, Davies (Inside the Hurricane; The Devil's Flu) offers a play-by-play account of the 1919 cross-country military caravan that doubled as a campaign for the Lincoln Highway. The potential here is extraordinary. Using the progress of the caravan and the metaphor of paving toward the future versus stagnating in the mud, Davies touches on the industrial and social factors that developed the small and mid-sized towns that line the highways and byways of the nation.

In 2005, Greetings from the Lincoln Highway: America's First Coast-to-Coast Road, a comprehensive coffee table book by Brian Butko, became the first complete guide to the road, with maps, directions, photos, postcards, memorabilia, and histories of towns, people, and places. A mix of research and on-the-road fun, the book placed the LHA's early history in the context of roadbuilding, politics, and geography, explaining why the Lincoln followed the path it did across the US, including the oft-forgotten Colorado Loop through Denver. Butko's book also incorporated quotes from early motoring memoirs and postcard messages—sometimes funny, sometimes painfully descriptive of early motoring woes—hence the Greetings title. Butko had previously written an exhaustive guide to the Lincoln Highway in Pennsylvania in 1996, which was revised and republished in 2002 with different photos and postcard images.[30]

In July 2007, the W.W. Norton Company published The Lincoln Highway, Coast-to-Coast from Times Square to the Golden Gate: The Great American Road Trip by Michael Wallis, best-selling author of Route 66, and voice in the movie Cars, and Michael Williamson, twice a Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer with The Washington Post.[31]

Completed in 2009, Stackpole Books published Lincoln Highway Companion: A Guide to America's First Coast-to-Coast Road, authored by Brian Butko. This handy glove-compartment guide contains carefully charted maps, must-see attractions, and places to eat and sleep that are slices of pure Americana. The book covers the major thirteen states the Lincoln Highway passes through, from New York to San Francisco, as well as the little-known Colorado loop and the Washington DC feeder loop.

Music

In 1914, the "Lincoln Highway March", a band score, was written by Lylord J. St. Claire.

In 1921, the popular two step march "Lincoln Highway" was composed by Harry J. Lincoln. The sheet music featuring an uncredited drawing of the road on the cover. Lincoln was also the publisher, and was based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania very near to where the highway passed through the city.

In 1922, another march titled "Lincoln Highway" was composed by George B. Lutz, and published by Kramer's Music House of Allentown, Pennsylvania. A video of a player-piano version can be viewed on YouTube.

In 1928, the song "Golden Gate" (Dreyer, Meyer, Rose, & Jolson), sung by Al Jolson, included the refrain: "Oh, Golden Gate, I'm comin' to ya / Golden Gate, sing Hallelujah / I'll live in the sun, love in the moon / Where every month is June. / A little sun-kissed blonde is comin' my way / Just beyond the Lincoln Highway / I'm goin' strong now, it won't be long now / Open up that Golden Gate."

In 1937, composer Harold Arlen and lyricist E. Y. Harburg (composers of "Over the Rainbow" and many other hits) wrote the song "God's Country", for the 1937 musical Hooray for What! The song was subsequently used for the finale of the 1939 MGM musical Babes in Arms, starring Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney. The song starts with the famous lyric: "Hey there, neighbor, goin' my way? / East or west on the Lincoln Highway? / Hey there Yankee, give out with a great big thank-ee; / You're in God's Country!"

In the 1940s, the Lincoln Highway radio show on NBC featured the theme song "When You Travel the Great Lincoln Highway". A rare surviving recording of the song can be found online.

Woody Guthrie's "the Asch Recordings" 1944 and 1945 included his song "Hard Traveling" with the line "I've been walking that Lincoln Highway / I thought you knowed".

In 1945, the title ballad (music by Earl Robinson, lyrics by Millard Lampell) from the 20th Century Fox World War II film A Walk In The Sun mentions the Lincoln Highway: "It's the same road they had / Coming out of Stalingrad, / It's that old Lincoln Highway back home, / It's wherever men fight to be free".

In 1974, the song "Old Thirty" was composed by Bill Fries (C.W. McCall) and Chip Davis for the album Wolf Creek Pass. An early verse contains the lyric: "She was known to all the truckers / As the Mighty Lincoln Highway / But to me She's still Old Thirty all the way".

In 1994, the song "Lincoln Highway Dub" is an all instrumental song created by the band Sublime in their album Robbin' the Hood. It features elements later used in the well-known song "Santeria", also by Sublime.

In 1996, Shadric Smith composed the country-western swing "Rollin' Down That Lincoln Highway" which was recorded in 2003 by Smith and Denny Osburn. In 2008, Smith revised some of the lyrics. The original 2003 recording of the song and the revised 2008 version can be found online. "Rollin' Down That Lincoln Highway" is one of two Lincoln Highway inspired songs that was featured in the 2014 documentary film 100 Years on the Lincoln Highway produced by Tom Manning for Wyoming PBS.

In 2004, Mark Rushton released the CD The Driver's Companion. The lead track is Rushton's composition "Theme from Lincoln Highway", an ambient electronic soundscape.

In 2006, Bruce Donnola composed "Lincoln Highway", a track on Donnola's album The Peaches of August, available on both iTunes and CD-Baby. A music video of the song appears on YouTube.

For the 2008 PBS documentary, A Ride Along the Lincoln Highway produced by Rick Sebak, Buddy McNutt composed the song "Goin' All the Way (on the Lincoln Highway)".

In 2010, singer-songwriter Chris Kennedy released the CD Postcards from Main Street, a collection of 11 odes to small towns, two-lane roads, and a simpler, slower life. His fourth track is "Looking for the Lincoln Highway". Kennedy is an associate professor of Communications at Western Wyoming Community College, in Rock Springs, Wyoming, a town along the Lincoln Highway. "Looking for the Lincoln Highway" is one of two Lincoln Highway inspired songs that was featured in the 2014 documentary film 100 Years on the Lincoln Highway produced by Tom Manning for Wyoming PBS.

In 2013, for the 100th Anniversary of the Lincoln Highway, Nils Anders Erickson composed the country song "Goin Down the Lincoln Highway: 100 Years in Three Minutes", featuring steel guitar and honky-tonk piano, with lyrics mentioning people "coming from Norway and the UK". The accompanying video, which can be viewed on YouTube, features over 300 images captured by Erickson of current and destroyed landmarks from Council Bluffs, Iowa, and three versions of the Historic Douglas St. Bridge. Erickson's intent is to create a version for every Lincoln Highway state.

In 2013, in celebration of the Lincoln Highway's Centennial, Nolan Stolz composed the symphony "Lincoln Highway Suite". The symphony has five movements: "From the Hudson", "Metals Heartland", "Prairie View", "Traversing the Mountains" and "Golden State Romp". The Dubuque Symphony premiered the composition June 2013.

Also in 2013, singer Cecelia Otto traveled the Lincoln Highway from New York to San Francisco for her project American Songline,[32] in which she performed vintage songs in period attire in venues along the highway. In 2015, she published a book recounting her journey and released an album of songs from her concert program; the album also featured several original songs about the highway, including "It's a Long Way to California" and "Land of Lincoln".

Radio

On March 16, 1940, NBC Radio introduced a Saturday morning dramatic show called Lincoln Highway sponsored by Shinola Polish, which featured stories of life along the route.[33][34] The show's introduction contained an error in noting the Lincoln Highway was identical to US 30 and ended in Portland. Many of the era's stars including Ethel Barrymore, Joe E. Brown, Claude Rains, Sam Levene, Burgess Meredith, and Joan Bennett made appearances on the show, which had an audience of more than 8 million before it left the air in 1942. A rare surviving recording of the show's theme song, "When You Travel the Great Lincoln Highway", survives online.

Television

On October 29, 2008, PBS premiered the documentary film, A Ride Along the Lincoln Highway, produced by Rick Sebak with WQED—TV in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[35] The Lincoln Highway Association awarded Sebak its first "Gregory M. Franzwa Award" at the 2009 LHA conference. The Franzwa Award is given to individuals who have made a significant contribution to the promotion of the Lincoln Highway, and is named in honor of Franzwa who was a founding member and the first president of the revitalized Lincoln Highway Association, in 1992.

The pilot episode of Boardwalk Empire, shown on HBO in the United States, beginning in September 2010, contains a scene showing Al Capone en route from New Jersey to Chicago. He passes a sign that says he is travelling on the Lincoln Highway and that Chicago is 200 miles (320 km) ahead (thus placing him in western Ohio). This episode is set in early 1920.

On March 9, 2014, Wyoming PBS premiered the Emmy Award-winning documentary film, 100 Years on the Lincoln Highway, produced by Tom Manning.[36] This hour-long documentary follows the route of the Lincoln Highway in Wyoming and explores many of the towns and landmarks along the way. Shot during its centennial year in 2013, the program features historians, authors, archeologists and Lincoln Highway enthusiasts explaining the history of the road and their fascination with its many permutations over the years. It also follows members of the official Lincoln Highway Association's Centennial Tour. Driving a collection of antique & modern automobiles spanning 100 years, they trace the original route of the Lincoln Highway across Wyoming.

Film

In 1919, Fox Film Corporation produced and released the feature The Lincoln Highwayman, a black and white silent film starring William Russell, Lois Lee, Frank Brownlee, Jack Connolly, Edward Peil, Sr., Harry Spingler, and Edwin B. Tilton.[37] The film was written and directed by Emmett J. Flynn, from an adaptation by Jules Furthman based on a 1917 one-act melodrama by Paul Dickey and Rol Cooper Megrue.[38] The story is about a masked bandit (the "Lincoln Highwayman") who terrorizes motorists on the highway in California. His latest victims are a San Francisco banker and his family on their way to a party. While the masked highwayman holds them up at gun point and steals the women's jewels, the banker's daughter Marian (Lois Lee) finds herself strangely attracted to him. When the family finally arrives at the party, they tell the guests their tale. Steele, a secret service man (Edward Piel), takes an interest in their encounter and starts working on the case. Jimmy Clunder (William Russell), who arrives late is talking to Marian when a locket falls out of his pocket. Marian recognizes it, and Clunder claims that he found it on the Lincoln Highway. She begins to suspect that he is the Lincoln Highwayman, as does Steele, Clunder's rival for Marian's love.[39]

In 1924, the Ford Motor Company produced and released Fording the Lincoln Highway. The 30-minute silent film documented the 10-millionth Model T Ford and its promotional tour on the Lincoln Highway. The car came off the assembly line of Ford's Highland Park Assembly Plant on June 15, 1924, which was the 16th year of Model T production. The milestone flivver led parades through most of the towns and cities along the Lincoln Highway. It was driven by Ford racer Frank Kulick. Several million people are estimated to have seen the vehicle, which was greeted by governors and mayors at each stop along the route.[40]

In 2016 a documentary named 21 Days Under the Sky chronicled a journey of four friends on Harley-Davidson motorcycles, riding the Lincoln Highway from San Francisco to New York.[41]

See also

- National Auto Trail

- United States Numbered Highways

- Interstate Highway System

- Interoceanic Highway

- Breezewood, Pennsylvania

- Lincoln Highway (Omaha)

- 1919 Motor Transport Corps convoy

- Frances McEwen Belford

- U.S. Route 66

Notes

- Greetings from the Lincoln Highway: America's First Coast-to-Coast Road lists mileages[2] based on LHA guidebooks and a 1913 Packard guide to the road, which gave the length as 3,388.6 miles (5,453.4 km) which is commonly rounded to 3,389 miles (5,454 km). The route, and its length, remained in constant flux in an effort to straighten the road; by 1924, it had been shortened to 3,142.6 miles (5,057.5 km). Interstate 80, the highway's modern replacement, stretches 2,900 miles (4,700 km).

- Greetings from the Lincoln Highway: America's First Coast-to-Coast Road notes the exact number concrete markers, tallied by researcher Russell Rein from Gael Hoag's log, as 2,437 posts.[15]

- Note: Many cities named streets after President Lincoln independently of the Lincoln Highway, so not every Lincoln Way is in fact the Lincoln Highway. Two examples in San Francisco are Lincoln Way along the south side of Golden Gate Park, and Lincoln Boulevard in the Presidio, neither of which was ever the Lincoln Highway.

References

- Weingroff, Richard F. (April 7, 2011). "The Lincoln Highway". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

-

- Butko, Brian (2005). Greetings from the Lincoln Highway: America's First Coast-to-Coast Road (1st ed.). Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8117-0128-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link).

- Davies, Pete (2002). American Road: The Story of an Epic Transcontinental Journey at the Dawn of the Motor Age. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805068832. See throughout, but especially index entry "Lincoln Highway route controversy".

- Calculated by the Lincoln Highway Association National Mapping Committee chaired by Paul Gilger, 2007

- Lincoln Highway Association. Official Map of the Lincoln Highway (Map). Lincoln Highway Association.

- "Lincoln Highway". Visit Kearney Nebraska. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- "Lincoln Highway Entering Wedge". The New York Times. August 27, 1911. sec. III and IV, p. 8. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- The Lincoln Highway: A Much-Loved Route, Coast to Coast. Rand McNally. 1999.

- McCarthy, Joe (June 1974). "The Lincoln Highway". American Heritage Magazine. 25 (4). Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- "How 'Lincoln Way' Project Now Stands". The New York Times. April 5, 1914. sec. 9, p. 8. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- "English Auto Club An Example Here". The New York Times. December 31, 1913. p. 12. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- "Would Post Notice About Auto Fines". The New York Times. January 26, 1914. p. 8. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- "Statue of Abraham Lincoln". Detroit: The History and Future of the Motor City. October 1, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- "Lincoln Pilgrimage". Great Lakes Council, Boy Scouts of America. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- Butko (2005), pp. 24–5.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form: The Lincoln Highway in Greene County, Iowa". July 15, 1992.

- Lincoln Highway Association. "Lincoln Highway Association". Lincoln Highway Association. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- Lincoln Highway Association. "2013 Lincoln Highway 100th Anniversary Tour". Lincoln Highway Association. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- "LH2013 Lincoln Highway Centennial Tour". LH2013 Lincoln Highway Centennial Tour. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- Lincoln Highway Association. "2015 Lincoln Highway Henry B. Joy Tour". Lincoln Highway Association. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- Packard Automobile Classics. "The Packard Club". Packard Automobile Classics. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- Packards International Motor Car Club. "Packards International Motor Car Club". Packards International Motor Car Club. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor. "Roadside Giants of the Lincoln Highway". Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- Anithakumari, A. M. & Girish, Rai. B. (January–March 2006). "Carotid Space Infection: A Cast Report" (PDF). Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery. Calcutta: B.K. Roy Chaudhuri. 58 (1): 95–7. doi:10.1007/BF02907756 (inactive March 23, 2020). ISSN 0973-7707. PMC 3450626. PMID 23120252. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- Gladding, Effie Price (1915). Across the Continent by the Lincoln Highway. New York: Brentano's. p. 111.

- Massey, Beatrice Larned (1920). It Might Have Been Worse: A Motor Trip from Coast to Coast. San Francisco: Harr Wagner Publishing Company. p. 143.

- Hokanson, Drake (1999). Lincoln Highway, the Main Street Across America (10th anniversary ed.). Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. ISBN 1-58729-113-4. OCLC 44962845.

- Hokanson, Drake (August 1985). "To Cross America, Early Motorists Took a Long Detour". Smithsonian. 16 (5): 58–65.

-

- Butko, Brian (2002). Pennsylvania Traveler's Guide: The Lincoln Highway (2nd ed.). Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2497-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallis, Michael & Williamson, Michael (2007). The Lincoln Highway: Coast to Coast from Times Square to the Golden Gate. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05938-0. OCLC 83758808.

- Brown, Rick (June 27, 2013). "Classically Trained Mezzo-Soprano to Perform Across the U.S." Kearney Hub. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- "Lincoln Highway (review)". Weekly Variety. March 20, 1940. p. 32. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 401. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

Lincoln Highway, dramatic anthology.

- Sebak, Rick (October 29, 2008). A Ride Along the Lincoln Highway. Pittsburgh: WQED-TV.

- Manning, Tom (2014). 100 Years on the Lincoln Highway. Riverton: Wyoming PBS.

- "'The Lincoln Highwayman' (1919)". TCM Movie Database. Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- "Dickey Writes Another: 'The Lincoln Highwayman' a Little Copy of 'Under Cover'". The New York Times. April 24, 1917. p. 9. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- Garza, Janiss. "'Lincoln Highwayman' (1920)". All Movie Guide. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- Lewis, David L.; McCarville, Mike & Sorensen, Lorin (1983). Ford, 1903 to 1984. New York: Beekman House. OCLC 10270117.

- "'21 Days Under the Sky' (2016)".

Further reading

- Kutz, Kevin (2006). Kevin Kutz's Lincoln Highway: Paintings and Drawings. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3264-2.

- Wallis, Michael & Williamson, Michael (2007). The Lincoln Highway: Coast to Coast from Times Square to the Golden Gate (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05938-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lincoln Highway. |

- Lincoln Highway Association website

- James Lin, The Lincoln Highway

- Lincoln Highway maps c. 1926, New York to Pittsburgh

- Lincoln Highway National Museum & Archives

- Lincoln Highway Digital Image Archive at the University of Michigan, Special Collections Library, Transportation History Collection

- Lincoln Highway Association Archive at the University of Michigan, Special Collections Library, Transportation History Collection

- 1959 color movie of the Lincoln Highway made by the Iowa State Highway Commission (ISHC), now the Iowa DOT (16 min).

- Eastern terminus sign on Google Street View

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. PA-592, "Lincoln Highway, Running from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh"