History of the United States (1776–1789)

Between 1776 and 1789 thirteen British colonies emerged as a new independent nation, the United States of America. Fighting in the American Revolutionary War started between colonial militias and the British Army in 1775. The Second Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. Under the leadership of General George Washington, the Continental Army and Navy defeated the British military securing the independence of the thirteen colonies. In 1789, the 13 states replaced the Articles of Confederation of 1777 with the Constitution of the United States of America. With its amendments it remains the fundamental governing law of the United States today.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the United States |

|

|

By ethnicity |

|

|

Background

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, British colonies in America had been largely left to their own devices by the crown; it was called salutary neglect.[1] The colonies were thus largely self-governing; half the white men in America could vote, compared to one percent in Britain. They developed their own political identities and systems which were in many ways separate from those in Britain. This new ideology was a decidedly republican political viewpoint, which rejected royalty, aristocracy, and in the name of corruption, called for sovereignty of the people and emphasized civic duty. In 1763 with British victory in the French and Indian War, this period of isolation came to an end with the Stamp Act of 1765. The British government began to impose taxes in a way that deliberately provoked the Americans, who complained that they were alien to the unwritten English Constitution because Americans were not represented in parliament. Parliament said the Americans were "virtually" represented and had no grounds for complaint.[2][3] From the Stamp Act of 1765 onward, disputes with London escalated. By 1772 the colonists began the transfer of political legitimacy to their own hands and started to form shadow governments built on committees of correspondence that coordinated protest and resistance. They called the First Continental Congress in 1774 to inaugurate a trade boycott against Britain. Twelve colonies were represented at the Congress. Georgia was under tight British control and did not attend.

When resistance in Boston culminated in the Boston Tea Party in 1773 with the dumping of taxed tea shipments into the harbor, London imposed the Intolerable Acts on the colony of Massachusetts, ended self-government, and sent in the Army to take control. The Patriots in Massachusetts and the other colonies readied their militias and prepared to fight.[4][5]

American Revolution

George Washington's roles

General Washington assumed five main roles during the war.[6]

First, he designed the overall strategy of the war, in cooperation with Congress. The goal was always independence. When France entered the war, he worked closely with the soldiers it sent—they were decisive in the great victory at Yorktown in 1781. Their help led to America winning the war overall.

Second, he provided leadership of troops against the main British forces in 1775–77 and again in 1781. He lost many of his battles, but he never surrendered his army during the war, and he continued to fight the British relentlessly until the war's end. Washington worked hard to develop a successful espionage system to detect British locations and plans. In 1778, he formed the Culper Ring to spy on the British movements in New York City. In 1780 it discovered Benedict Arnold was a traitor.[7]

Third, he was charged with selecting and guiding the generals. In June 1776, Congress made its first attempt at running the war effort with the committee known as "Board of War and Ordnance", succeeded by the Board of War in July 1777, a committee which eventually included members of the military.[8][9] The command structure of the armed forces was a hodgepodge of Congressional appointees (and Congress sometimes made those appointments without Washington's input) with state-appointments filling the lower ranks. The results of his general staff were mixed, as some of his favorites never mastered the art of command, such as John Sullivan. Eventually, he found capable officers such as Nathanael Greene, Daniel Morgan, Henry Knox (chief of artillery), and Alexander Hamilton (chief of staff). The American officers never equaled their opponents in tactics and maneuver, and they lost most of the pitched battles. The great successes at Boston (1776), Saratoga (1777), and Yorktown (1781) came from trapping the British far from base with much larger numbers of troops.[10]

Fourth he took charge of training the army and providing supplies, from food to gunpowder to tents. He recruited regulars and assigned Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, a veteran of the Prussian general staff, to train them. He transformed Washington's army into a disciplined and effective force.[11] The war effort and getting supplies to the troops were under the purview of Congress, but Washington pressured the Congress to provide the essentials. There was never nearly enough.[12]

Washington's fifth and most important role in the war effort was the embodiment of armed resistance to the Crown, serving as the representative man of the Revolution. His long-term strategy was to maintain an army in the field at all times, and eventually this strategy worked. His enormous personal and political stature and his political skills kept Congress, the army, the French, the militias, and the states all pointed toward a common goal. Furthermore, he permanently established the principle of civilian supremacy in military affairs by voluntarily resigning his commission and disbanding his army when the war was won, rather than declaring himself monarch. He also helped to overcome the distrust of a standing army by his constant reiteration that well-disciplined professional soldiers counted for twice as much as poorly trained and led militias.[13]

Military hostilities begin

On April 19, 1775, the royal military governor sent a detachment of troops to seize gunpowder and arrest local leaders in Concord. At Lexington, Massachusetts, shots broke out with the Lexington militia, leaving eight colonists dead. The British failed to find their targets in Concord, and as they retreated back to Boston, the British came under continuous assault by upwards of 3,800 militia who had prepared an ambush. The Battle of Lexington and Concord ignited the American Revolutionary War. As news spread, local shadow governments (called "committees of correspondence") in each of the 13 colonies drove out royal officials and sent militiamen to Boston to besiege the British there.[14][15]

The Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the aftermath of armed clashes in April. With all thirteen colonies represented, it immediately began to organize itself as a central government with control over the diplomacy and instructed the colonies to write constitutions for themselves as states. On June 1775, George Washington, a charismatic Virginia political leader with combat experience was unanimously appointed commander of a newly organized Continental Army. He took command in Boston and sent for artillery to barrage the British.[16] In every state, a minority professed loyalty to the King, but nowhere did they have power. These Loyalists were kept under close watch by standing Committees of Safety created by the Provincial Congresses. The unwritten rule was such people could remain silent, but vocal or financial or military support for the King would not be tolerated. The estates of outspoken Loyalists were seized; they fled to British-controlled territory, especially New York City.[17]

Invasion of Canada

During the winter of 1775–76, an attempt by the Patriots to capture Quebec failed, and the buildup of British forces at Halifax, Nova Scotia, precluded that colony from joining the 13 colonies. The Americans were able to capture a British fort at Ticonderoga, New York, and to drag its cannon over the snow to the outskirts of Boston. The appearance of troops and a cannon on Dorchester Heights outside Boston led the British Army to evacuate the city on March 17, 1776.[18]

Declaration of Independence

%2C_by_John_Trumbull.jpg)

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, still meeting in Philadelphia, voted unanimously to declare the independence as the "United States of America". Two days later, on July 4, Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence. The drafting of the Declaration was the responsibility of a Committee of Five, which included John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, and Benjamin Franklin; it was drafted by Jefferson and revised by the others and the Congress as a whole. It contended that "all men are created equal" with "certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness", and that "to secure these rights governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed", as well as listing the main colonial grievances against the crown.[19] July 4 ever since has been celebrated as the birthday of the United States.

The Founding Fathers represented a cross-section of Patriot leadership. According to a study of the biographies of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence:

- The Signers came for the most part from an educated elite, were residents of older settlements, and belonged with a few exceptions to a moderately well-to-do class representing only a fraction of the population. Native or born overseas, they were of British stock and of the Protestant faith.[20][21]

Campaigns of 1776 and 1777

The British returned in force in August 1776, landing in New York and defeating the fledgling Continental Army at the Battle of Long Island in one of the largest engagements of the war. They quickly seized New York City and nearly captured General Washington and his army. The British made the city their main political and military base of operations in North America, holding it until late 1783. Patriot evacuation and British military occupation made the city the destination for Loyalist refugees, and a focal point of Washington's intelligence network.[22][23][24] The British soon seized New Jersey, and American fortunes looked dim; Thomas Paine proclaimed "these are the times that try men's souls". But Washington struck back in a surprise attack, crossing the icy Delaware River into New Jersey and defeated British armies at Trenton and Princeton, thereby regaining New Jersey. The victories gave an important boost to Patriots at a time when morale was flagging, and have become iconic images of the war.[25]

In early 1777, a grand British strategic plan, the Saratoga Campaign, was drafted in London. The plan called for two British armies to converge on Albany, New York from the north and south, dividing the colonies in two and separating New England from the rest. Failed communications and poor planning resulted in the army descending from Canada, commanded by General John Burgoyne, bogging down in dense forest north of Albany. Meanwhile, the British Army that was supposed to advance up the Hudson River to meet Burgoyne went instead to Philadelphia, in a vain attempt to end the war by capturing the American capital city. Burgoyne's army was overwhelmed at Saratoga by a swarming of local militia, spearheaded by a cadre of American regulars.[26] The battle showed the British, who had until then considered the colonials a ragtag mob that could easily be dispersed, that the Americans had the strength and determination to fight on. Said one British officer:

The courage and obstinacy with which the Americans fought were the astonishment of everyone, and we now became fully convinced that they are not that contemptible enemy we had hitherto imagined them, incapable of standing a regular engagement, and that they would only fight behind strong and powerful works.[27]

The American victory at Saratoga led the French into an open military alliance with the United States through the Treaty of Alliance (1778). France was soon joined by Spain and the Netherlands, both major naval powers with an interest in undermining British strength. Britain now faced a major European war, and the involvement of the French navy neutralized their previous dominance of the war on the sea. Britain was without allies and faced the prospect of invasion across the English Channel.[28]

The British move South, 1778–1783

With the British in control of most northern coastal cities and Patriot forces in control of the hinterlands, the British attempted to force a result by a campaign to seize the southern states. With limited regular troops at their disposal, the British commanders realized that success depended on a large-scale mobilization of Loyalists.[29]

In late December 1778, the British had captured Savannah. In 1780 they launched a fresh invasion and took Charleston as well. A significant victory at the Battle of Camden meant that the invaders soon controlled most of Georgia and South Carolina. The British set up a network of forts inland, hoping the Loyalists would rally to the flag. Not enough Loyalists turned out, however, and the British had to move out. They fought their way north into North Carolina and Virginia, with a severely weakened army. Behind them, much of the territory they left dissolved into a chaotic guerrilla war, as the bands of Loyalists, one by one, were overwhelmed by the patriots.

The British army under Lord Cornwallis marched to Yorktown, Virginia where they expected to be rescued by a British fleet. When that fleet was defeated by a French fleet, however, they were trapped, and were surrounded by a much stronger force of Americans and French under Washington's command. On October 19, 1781, Cornwallis surrendered.[30]

News of the defeat effectively ended the fighting in America, although the naval war continued. Support for the conflict had never been strong in Britain, where many sympathized with the rebels, but now it reached a new low. King George III personally wanted to fight on, but he lost control of Parliament, and had to agree to peace negotiations.

Peace and memory

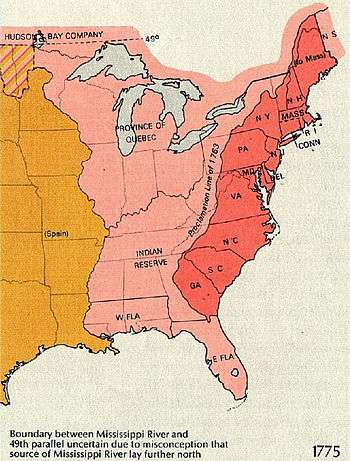

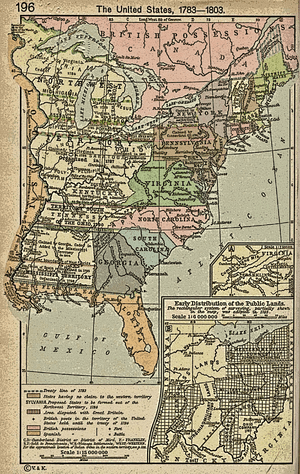

Long negotiations resulted in the Treaty of Paris (1783), which provided highly favorable boundaries for the United States; it included nearly all land east of the Mississippi River and south of Canada, except British West Florida, which was awarded to Spain. Encompassing a vast region nearly as large as Western Europe, the western territories contained a few thousand American pioneers and tens of thousands of Indians, most of whom had been allied to the British but were now abandoned by London.[31]

Every nation constructs and honors the memory of its founding, and following generations use it to establish its identity and define patriotism.[32] The memory of the Founding and the Revolution has long been used as a political weapon. For example, the right-wing "Tea Party movement" of the 21st century explicitly memorialized the Boston Tea Party as a protest against intrusive government.[33]

The Patriot reliance on Catholic France for military, financial and diplomatic aid led to a sharp drop in anti-Catholic rhetoric. Indeed the king replaced the pope as the demon patriots had to fight against. Anti-Catholicism remained strong among Loyalists, some of whom went to Canada after the war while 80% remained in the new nation. By the 1780s, Catholics were extended legal toleration in all of the New England states that previously had been so hostile. "In the midst of war and crisis, New Englanders gave up not only their allegiance to Britain but one of their most dearly held prejudices."[34]

Historians have portrayed the Revolution as the main source of the non-denominational "American civil religion" that has shaped patriotism, and the memory and meaning of the nation's birth ever since.[35] Key events and people were viewed as icons of fundamental virtues. Thus the Revolution produced a Moses-like leader (George Washington),[36] prophets (Thomas Jefferson, Tom Paine), disciples (Alexander Hamilton, James Madison) and martyrs (Boston Massacre, Nathan Hale), as well as devils (Benedict Arnold). There are sacred places (Valley Forge, Bunker Hill), rituals (Boston Tea Party), emblems (the new flag), sacred days (Independence Day), and sacred scriptures whose every sentence is carefully studied (The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights).[37]

Confederation Period: 1783–1789

During the 1780s, the nation was a loose confederation of 13 states and was beset with a wide array of foreign and domestic problems. The states engaged in small scale trade wars against each other, and they had difficulty suppressing insurrections such as Shays Rebellion in Massachusetts. The treasury was empty and there was no way to pay the war debts. There was no national executive authority. The world was at peace and the economy flourished. Some historians depict a bleak challenging time for the new nation. Merrill Jensen and others say the term “Critical Period” is exaggerated, and that it was also a time of economic growth and political maturation.[38][39]

Articles of Confederation

The Treaty of Paris left the United States independent and at peace but with an unsettled governmental structure. The Second Continental Congress had drawn up Articles of Confederation on November 15, 1777, to regularize its own status. These described a permanent confederation, but granted to the Congress—the only federal institution—little power to finance itself or to ensure that its resolutions were enforced. There was no president and no judiciary.

Although historians generally agree that the Articles were too weak to hold the fast-growing nation together, they do give Congress credit for resolving the conflict between the states over ownership of the western territories. The states voluntarily turned over their lands to national control. The Land Ordinance of 1785 and Northwest Ordinance created territorial government, set up protocols for the admission of new states, the division of land into useful units, and set aside land in each township for public use. This system represented a sharp break from imperial colonization, as in Europe, and provided the basis for the rest of American continental expansion through the 19th Century.[40]

By 1783, with the end of the British blockade, the new nation was regaining its prosperity. However, trade opportunities were restricted by the mercantilist policies of the European powers. Before the war the Americans had shipped food and other products to the British colonies in the Caribbean ( British West Indies ), but now these ports were closed, since only British ships could trade there. France and Spain had similar policies for their empires. The former imposed restrictions on imports of New England fish and Chesapeake tobacco. New Orleans was closed by the Spanish, hampering settlement of the West, although it didn't stop frontiersmen from pouring west in great numbers. Simultaneously, American manufacturers faced sharp competition from British products which were suddenly available again. The inability of the Congress to redeem the currency or the public debts incurred during the war, or to facilitate trade and financial links among the states aggravated a gloomy situation. In 1786–87, Shays's Rebellion, an uprising of farmers in western Massachusetts against the state court system, threatened the stability of state government and the Congress was powerless to help.

The Continental Congress did have power to print paper money; it printed so much that its value plunged until the expression "not worth a continental" was used for some worthless item. Congress could not levy taxes and could only make requisitions upon the states, which did not respond generously. Less than a million and a half dollars came into the treasury between 1781 and 1784, although the states had been asked for two million in 1783 alone. In 1785, Alexander Hamilton issued a curt statement that the Treasury had received absolutely no taxes from New York for the year.

States handled their debts with varying levels of success. The South for the most part refused to pay its debts off, which was damaging to local banks, but Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia fared well due to their production of cash crops such as cotton and tobacco. South Carolina would have done the same except for a series of crop failures. Maryland suffered from financial chaos and political infighting. New York and Pennsylvania fared well, although the latter also suffered from political quarrels. New Jersey, New Hampshire, Delaware, and Connecticut struggled. Massachusetts was in a state of virtual civil war (see above) and suffered from high taxes and the decline of its economy. Rhode Island alone among the New England states prospered and mostly because of its notorious harboring of pirates and smugglers.

When Adams went to London in 1785 as the first representative of the United States, he found it impossible to secure a treaty for unrestricted commerce. Demands were made for favors and there was no assurance that individual states would agree to a treaty. Adams stated it was necessary for the states to confer the power of passing navigation laws to Congress, or that the states themselves pass retaliatory acts against Great Britain. Congress had already requested and failed to get power over navigation laws. Meanwhile, each state acted individually against Great Britain to little effect. When other New England states closed their ports to British shipping, Connecticut hastened to profit by opening its ports.

By 1787 Congress was unable to protect manufacturing and shipping. State legislatures were unable or unwilling to resist attacks upon private contracts and public credit. Land speculators expected no rise in values when the government could not defend its borders nor protect its frontier population.[41]

The idea of a convention to revise the Articles of Confederation grew in favor. Alexander Hamilton realized while serving as Washington's top aide that a strong central government was necessary to avoid foreign intervention and allay the frustrations due to an ineffectual Congress. Hamilton led a group of like-minded nationalists, won Washington's endorsement, and convened the Annapolis Convention in 1786 to petition Congress to call a constitutional convention to meet in Philadelphia to remedy the long-term crisis.[42]

Constitutional Convention

Congress, meeting in New York, called on each state to send delegates to a Constitutional Convention, meeting in Philadelphia. While the stated purpose of the convention was to amend the Articles of Confederation, many delegates, including James Madison and George Washington, wanted to use it to craft a new constitution for the United States. The Convention convened in May 1787 and the delegates immediately selected Washington to preside over them. Madison soon proved the driving force behind the Convention, engineering the compromises necessary to create a government that was both strong and acceptable to all of the states. The Constitution, proposed by the Convention, called for a federal government—limited in scope but independent of and superior to the states—within its assigned role able to tax and equipped with both Executive and Judicial branches as well as a two house legislature. The national legislature—or Congress—envisioned by the Convention embodied the key compromise of the Convention between the small states which wanted to retain the power they had under the one state/one vote Congress of the Articles of Confederation and the large states which wanted the weight of their larger populations and wealth to have a proportionate share of power. The upper House—the Senate—would represent the states equally, while the House of Representatives would be elected from districts of approximately equal population.[43]

The Constitution itself called for ratification by state conventions specially elected for the purpose, and the Confederation Congress recommended the Constitution to the states, asking that ratification conventions be called.

Several of the smaller states, led by Delaware, embraced the Constitution with little reservation. But in the most populous two states, New York and Virginia, the matter became one of controversy. Virginia had been the first successful British colony in North America, had a large population, and its political leadership had played prominent roles in the Revolution. New York was likewise large and populous; with the best situated and sited port on the coast, the state was essential for the success of the United States. Local New York politics were tightly controlled by a parochial elite led by Governor George Clinton, and local political leaders did not want to share their power with the national politicians. The New York ratification convention became the focus for a struggle over the wisdom of adopting the Constitution.

Those opposed to the new Constitution became known as the Anti-Federalists. They generally were local rather than cosmopolitan in perspective, oriented to plantations and farms rather than commerce or finance, and wanted strong state governments and a weak national government. According to political scientist James Q. Wilson the Anti-Federalists:

- were much more committed to strong states and a weak national government....A strong national government, they felt, would be distant from the people and would use its powers to annihilate or absorb the functions that properly belonged to the states.[44]

Campaign for ratification

Those who advocated the Constitution took the name Federalists and quickly gained supporters throughout the nation. The most influential Federalists were Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, the anonymous authors of The Federalist Papers, a series of 85 essays published in New York newspapers, under the pen name "Publius". The papers became seminal documents for the new United States and have often been cited by jurists. These were written to sway the closely divided New York legislature.[45]

Opponents of the plan for stronger government, the Anti-Federalists, feared that a government with the power to tax would soon become as despotic and corrupt as Great Britain had been only decades earlier. The most notable Anti-federalist writers included Patrick Henry and George Mason, who demanded a Bill of Rights in the Constitution.

The Federalists gained a great deal of prestige and advantage from the approval of George Washington, who had chaired the Constitutional Convention. Thomas Jefferson, serving as Minister to France at the time, had reservations about the proposed Constitution. He resolved to remain neutral in the debate and to accept either outcome.

Promises of a Bill of Rights from Madison secured ratification in Virginia, while in New York, the Clintons, who controlled New York politics, found themselves outmaneuvered as Hamilton secured ratification by a 30–27 vote.[46] North Carolina and Rhode Island eventually signed on to make it unanimous among the 13 states.[47]

The old Confederation Congress now set elections to the new Congress as well as the first presidential election. The electoral college unanimously chose Washington as first President; John Adams became the first Vice President. New York was designated as the national capital; they were inaugurated in April 1789 at Federal Hall.

Under the leadership of Madison, the first Congress set up all the necessary government agencies, and made good on the Federalist pledge of a Bill of Rights.[48] The new government at first had no political parties. Alexander Hamilton in 1790–92 created a national network of friends of the government that became the Federalist party; it controlled the national government until 1801.

However, there continued to be a strong sentiment in favor of states' rights and a limited federal government. This became the platform of a new party, the Republican or Democratic-Republican Party, which assumed the role of opposition to the Federalists. Jefferson and Madison were its founders and leaders. The Democratic-Republicans strongly opposed Hamilton's First Bank of the United States. American foreign policy was dominated by the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars between the United Kingdom and France. The Republicans supported France, encouraging the French Revolution as a force for democracy, while the Washington administration favored continued peace and commerce with Britain, signing the Jay Treaty much to the disgust of Democratic-Republicans, who accused Hamilton and the Federalists of supporting aristocracy and tyranny. John Adams succeeded Washington as President in 1797 and continued the policies of his administration. The Jeffersonian Republicans took control of the Federal government in 1801 and the Federalists never returned to power.

Westward expansion

Only a few thousand Americans had settled west of the Appalachian Mountains prior to 1775. Settlement continued, and by 1782 25,000 Americans had settled in Transappalachia.[49] After the war, American settlement in the region continued. Though life in these new lands proved hard for many, western settlement offered the prize of property, an unrealistic aspiration for some in the East.[50] Westward expansion stirred enthusiasm even in those who did not move west, and many leading Americans, including Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and John Jay, purchased lands in the west.[51] Land speculators founded groups like the Ohio Company, which acquired title to vast tracts of land in the west and often came into conflict with settlers.[52] Washington and others co-founded the Potomac Company to build a canal linking the Potomac River with Ohio River. Washington hoped that this canal would provide a cultural and economic link between the east and west, thus ensuring that the West would not ultimately secede.[53]

In 1784, Virginia formally ceded its claims north of the Ohio River, and Congress created a government for the region now known as the Old Northwest with the Land Ordinance of 1784 and the Land Ordinance of 1785. These laws established the principle that Old Northwest would be governed by a territorial government, under the aegis of Congress, until it reached a certain level of political and economic development. At that point, the former territories would enter the union as states, with rights equal to that of any other state.[54] The federal territory stretched across most of the area west of Pennsylvania and north of the Ohio River, though Connecticut retained a small part of its claim in the West in the form of the Connecticut Western Reserve, a strip of land south of Lake Erie.[55] In 1787, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, which granted Congress greater control of the region by establishing the Northwest Territory. Under the new arrangement, many of the formerly elected officials of the territory were instead appointed by Congress.[56] In order to attract Northern settlers, Congress outlawed slavery in the Northwest Territory, though it also passed a fugitive slave law to appease the Southern states.[57]

While the Old Northwest fell under the control of the federal government, Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia retained control of the Old Southwest; each state claimed to extend west to the Mississippi River. In 1784, settlers in western North Carolina sought statehood as the State of Franklin, but their efforts were denied by Congress, which did not want to set a precedent regarding the secession of states.[58] By the 1790 Census, the populations of Tennessee and Kentucky had grown dramatically to 73,000 and 35,000, respectively. Kentucky, Tennessee, and Vermont would all gain statehood between 1791 and 1795.[59] With the aid of Britain and Spain, Native Americans resisted western settlement. Spain's 1784 closure of the Mississippi River denied access to the sea for the exports of Western farmers, greatly impeding efforts to settle the West[60] The British had restricted settlement of the trans-Appalachian lands prior to 1776, and they continued to supply arms to Native Americans after the signing of the Treaty of Paris. Between 1783 and 1787, hundreds of settlers died in low-level conflicts with Native Americans, and these conflicts discouraged further settlement.[61] As Congress provided little military support against the Native Americans, most of the fighting was done by the settlers.[62] By the end of the decade, the frontier was engulfed in the Northwest Indian War against a confederation of Native American tribes. These Native Americans sought the creation of an independent Indian barrier state with the support of the British, posing a major foreign policy challenge to the United States.[63]

See also

References

- Edwin J. Perkins, "Forty Years of Salutary Neglect: A Retrospective." Reviews in American History 40#3 (2012): 370–375 online.

- Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution (2003) ch 15–17

- Richard Alan Ryerson, The Revolution is Now Begun: The Radical Committees of Philadelphia, 1765–1776 (2012).

- Greene and Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution (2003) ch 24

- Krull, Kathleen (2013). What was the Boston Tea Party?. Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 9780448462882.

- R. Don Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition (1985) ch 3

- Alexander Rose, Washington's Spies (2006). pp 258–61.

- William Gardner Bell (2005). Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff, 1775-2005: Portraits & Biographical Sketches of the United States Army's Senior Officer. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780160873300.

- Douglas S. Freeman, and Richard Harwell, Washington (1968) p 42.

- Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition (1985) ch 3

- Arnold Whitridge, "Baron von Steuben, Washington's Drillmaster." History Today (July 1976) 26#7 pp 429-36.

- E. Wayne Carp, To Starve the Army at Pleasure: Continental Army Administration and American Political Culture, 1775-1783 (1990) p 220.

- Edward G. Lengel, General George Washington: A Military Life (2005) pp 365-71.

- Robert A. Gross, The minutemen"(1976).

- David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere's ride (1994).

- Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (2011) pp 186–94

- Greene and Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution (2003) ch 29

- McCullough, 1776

- Greene and Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution (2003) ch 32

- Caroline Robbins, "Decision in '76: Reflections on the 56 Signers." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Vol. 89 pp 72-87, quote at p 86.

- See also Richard D. Brown, "The Founding Fathers of 1776 and 1787: A collective view." William and Mary Quarterly (1976) 33#3: 465-480. online

- Barnet Schecter, The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution (2002)

- McCullough, 1776.

- Andrew J. O'Shaughnessy, "Military Genius?: The Generalship of George Washington." Reviews in American History 42.3 (2014): 405–410. online

- David Hackett Fischer, Washington's Crossing (2005)

- Michael O. Logusz, With Musket And Tomahawk: The Saratoga Campaign and the Wilderness War of 1777 (2010)

- Victor Brooks; Robert Hohwald (1999). How America Fought Its Wars: Military Strategy from the American Revolution to the Civil War. Da Capo Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-58097-002-0.

- Howard Jones, Crucible of power: a history of American foreign relations to 1913 (2002) p. 12

- Henry Lumpkin, From Savannah to Yorktown: The American Revolution in the South (2000)

- Richard M. Ketchum, Victory at Yorktown: The Campaign That Won the Revolution (2004)

- Ronald Hoffman, and Peter J. Albert, eds. Peace and the Peacemakers: The Treaty of 1783 (1986).

- Barry Schwartz, "The social context of commemoration: A study in collective memory." Social forces 61.2 (1982): 374–402. online

- Jill Lepore, The Whites Of Their Eyes: The Tea Party’s Revolution and the Battle Over American History (Princeton University Press, 2010).

- Francis Cogliano, No King, No Popery: Anti-Catholicism in Revolutionary New England (1995) pp 154-55, quote p 155. online

- Barry Schwartz, "The social context of commemoration: A study in collective memory." Social forces 61.2 (1982): 374–402. online

- Robert P. Hay, "George Washington: American Moses," American Quarterly (1969) 21#4 pp 780–91 in JSTOR

- Catherine L. Albanese, Sons of the Fathers: The Civil Religion of the American Revolution (1977)

- Merrill Jensen, The New Nation: A History of the United States During the Confederation, 1781–1789 (1968).

- Bouton, Terry (2012). "The Trials of the Confederation". In Gray, Edward G.; Kamensky, Jane (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution. pp. 370–87.

- Richard Morris, The Forging of the Union, 1781–1789 (1988), is the standard scholarly history

- Jack N. Rakove, "The Collapse of the Articles of Confederation," in The American Founding: Essays on the Formation of the Constitution ed. by J. Jackson Barlow, Leonard W. Levy and Ken Masugi (1988) pp 225–45

- Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (2004)

- David O. Stewart, The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution (2008)

- James Wilson (2008). American Government: Brief Edition. Cengage Learning. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0547212760..

- Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788 (2010) p 84

- Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788 (2010) p 396

- Leonard W. Levy and Dennis J. Mahoney, The Framing and Ratification of the Constitution (1987)

- The Akhil Reed Amar The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction (2000)

- Walter Nugent, Habits of Empire: A History of American Expansion (2008) pp. 13–15

- John Ferling, A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic (2003), pp. 257–258

- Nugent (2008), pp. 22–23

- Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: the American Revolution, 1763–1789 (2005), pp. 610–611

- Maier (2010), pp. 9–11

- Middlekauff (2005), pp. 609–611

- Middlekauff (2005), p. 647

- Middlekauff (2005), pp. 609–611

- Alan Taylor, American Revolutions A Continental History, 1750–1804 (2016), pp. 341–342

- Taylor (2016), p. 340-344.

- David P. Currie (1997). The Constitution in Congress: The Federalist Period, 1789-1801. p. 221. ISBN 9780226131146.

- Ferling (2003), pp. 264–265

- Ferling (2003), pp. 264–265

- Taylor (2016), p. 343

- George Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (2008), pp. 43–44, 61-62

Further reading

- Alden, John R. A history of the American Revolution (1966) 644pp online to borrow

- Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777 (2019) (vol 1 of his 'The Revolution Trilogy'); called, "one of the best books written on the American War for Independence," [Journal of Military History Jan 2020 p 268]; the maps are online here

- Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life (2010), Pulitzer Prize

- Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton (2004)

- Cogliano, Francis D. Revolutionary America, 1763–1815; A Political History (2008), British textbook

- Ellis, Joseph J. Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation (2000)

- Ellis, Joseph J. Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence (2013) on 1776

- Ferling, John. A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic (2003) online edition

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, and Richard A. Ryerson, eds. The Encyclopedia of the American Revolutionary War: A Political, Social, and Military History (5 vol. 2006) 1000 entries by 150 experts, covering all topics

- Graebner, Norman A., Richard Dean Burns, and Joseph M. Siracusa. Foreign Affairs and the Founding Fathers: From Confederation to Constitution, 1776–1787 (Praeger, 2011) 199 pp.

- Gray, Edward G., and Jane Kamensky, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution (2013) 672 pp; 33 topical essays by scholars

- Greene, Jack P. and J.R. Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution (2nd ed, 2003), excerpt and text search, 90 essays by leading scholars; strong on all political, social and international themes; thin on military

- Hattem, Michael D. "The Historiography of the American Revolution" Journal of the American Revolution (2013) online outlines ten different scholarly approaches to the Revolution

- Higginbotham, Don. The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763–1789. Massachusetts:Northeastern University Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0-93035-043-7. Online in ACLS History E-book Project. Comprehensive coverage of military and other aspects of the war.

- Jensen, Merrill. "The Idea of a National Government During the American Revolution," Political Science Quarterly (1943) 58#3 pp: 356–379 in JSTOR

- Jensen, Merrill. The Articles of Confederation: An Interpretation of the Social-Constitutional History of the American Revolution, 1774–1781 (1959)

- Jensen, Merrill. The New Nation: A History of the United States During the Confederation, 1781–1789 (1981)

- Kerber, Linda K. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (1979)

- McCullough, David. 1776 (2005)

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789. (2nd ed. 2005). ISBN 0-19-516247-1. 696pp online edition

- Miller, John C. Triumph of Freedom, 1775–1783 (1948) online edition

- Morris, Richard B. The Forging of the Union, 1781–1789 (The New American Nation series) (ISBN 006015733X) (1987)

- Neimeyer, Charles Patrick. America Goes to War: A Social History of the Continental Army (1995) complete text online

- Nevins, Allan; The American States during and after the Revolution, 1775–1789 (1927) online edition.

- Norton, Mary Beth. 1774: The Long Year of Revolution (2020) online review by Gordon S. Wood

- Shachtman, Tom. The Founding Fortunes: How the Wealthy Paid for and Profited from America's Revolution (St. Martin's Press, 2020) popular economic history covers 1763 to 1813; online review

- Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750–1804 (2016) 704pp; recent survey by leading scholar

- Wood, Gordon S. The American Revolution: A History (2003), short survey by leading scholar

Primary sources

- Commager, Henry Steele and Morris, Richard B., eds. The Spirit of 'Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution As Told by Participants (1975) (ISBN 0060108347)

- Humphrey; Carol Sue, ed. The Revolutionary Era: Primary Documents on Events from 1776 to 1800 Greenwood Press, 2003

- Morison, S. E. ed. Sources and Documents Illustrating the American Revolution, 1764–1788, and the Formation of the Federal Constitution (1923)

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: US History |

- Interactive Google Map of the American Revolution Zoom in on the actual forts and battlefields of the American Revolution, complete with Wikipedia linked descriptions of each battle