Samaná Americans

The Samaná Americans (Americanos de Samaná) are a minority cultural sub-group that inhabits the Peninsula of Samaná in the Dominican Republic.

History

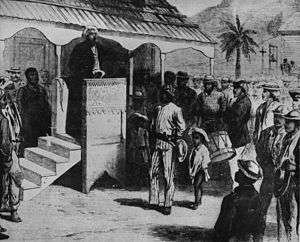

Most of the Samaná Americans are descendants of African Americans who, beginning in 1824, immigrated to Hispaniola—then under Haitian administration—benefiting from the favorable pro-Black immigration policy of president Jean Pierre Boyer. Jonathas Granville traveled to the U.S. in May–June 1824 in response to a letter that Loring D. Dewey had sent to Boyer. While in the U.S., Granville met with other abolitionists, like Richard Allen, Samuel Cornish, and Benjamin Lundy to organize the campaign for what was coined the Haitian emigration. The result was successful, as more than 6,000 of emigrants responding in less than a year. After that, however, the settlements met with multiple problems and many returned. However, many stayed and among those who stayed, enclaves in Puerto Plata and Santo Domingo were clearly evident by the time of Frederick Douglass's visit in 1871. But the most distinct of all the enclaves was the one in Samaná, which has survived until today. They constitute a recognizable and sizable cultural enclave and a few of its members are native Samaná English speakers. Aware of its distinctive heritage, the community, whose peculiar culture distinguishes them from the rest of Dominicans, refers to itself as Samaná Americans, and is referred to by fellow Dominicans as los americanos de Samaná.

Cultural Distinctiveness

Crucially, they maintain many elements of 19th-century African American culture—such as their variety of African American English, cuisine, games, and community services associations— that have since disappeared in the United States. Cultural exchanges with other groups in the area, like the Samaná Haitian communities and the Spanish-speaking majority, have been inevitable. But for most of its history, the English-speaking enclave has kept to itself, favoring, instead, intermarriages and reciprocal relations with other Black immigrant groups that are also Protestant and English-speakers, like the so-called cocolos. This is due to the relative isolation of the community, which until the 20th century was accessible only by boat due to the lack of roads connecting them to the rest of the island. Most follow the African Methodist Episcopal and Wesleyan denominations that their ancestors brought with them to the island.[1]

Current Days

While it is difficult to estimate the number of Samaná Americans today due to exogamy and emigration from the peninsula, the number of Samaná English speakers was once estimated to be around 8,000.[2] Such numbers have decreased considerably as the linguists doing research in the community relate; a difficulty in finding SE speakers even among the elderly.[3] No monolingual English speakers remain; all Samaná Americans who speak English also speak Spanish. As a result of the influence of mainstream Dominican culture (including compulsory Spanish-language education), many markers of their culture appear to be in decline.[4]

See also

- Haitian emigration

- Samaná Province

- Colonization Societies

- American Colonization Society

- Americo-Liberians

- American fugitives in Cuba

References

- Hidalgo, Dennis R. (2001). From North America to Hispaniola: First Free Black Emigration and Settlements in Hispaniola. Mt. Pleasant, MI: Central Michigan University. pp. 1–28.

- Ethnologue report for English; Samaná English is described under the heading "Dominican Republic"

- Davis, Martha Ellen (2007). "La historia de los inmigrantes afro-americanos y sus iglesias en Samaná según el reverendo Nehemiah Willmore" (PDF). Boletín del Archivo General de la Nación. 159: 237–245.

- Soraya Aracena, Los inmigrantes norteamericanos de Samaná. (Santo Domingo: Helvetas Asociación Suiza para la Cooperación Internacional, 2000)

External links

- The website of photographers Andrea Robbins and Max Becher contains a collection of portraits of present-day Samaná Americans. Scroll down to "Samaná" on the left-hand menu.

- Interview with enclave's historian Martha Willmore

- Clips of a documentary by Nestor Montilla Sr. that depicts the saga of thousands of free African-Americans who fled and settled in Samaná