Brooks–Baxter War

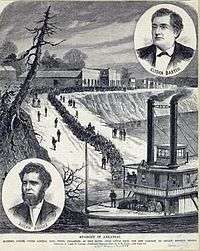

The Brooks–Baxter War (or sometimes referred to as the Brooks–Baxter Affair) was an armed conflict in Little Rock, Arkansas, in the United States, in 1874 between factions of the Republican Party over the disputed 1872 state gubernatorial election. The victor in the end was the "Minstrel" faction (supported by the 'carpetbaggers') led by Elisha Baxter over the "Brindle Tail" faction (supported by 'scalawags' and freedmen) led by Joseph Brooks.

| Brooks—Baxter War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Republican Party

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Elisha Baxter Robert C. Newton (Arkansas state militia) |

Joseph Brooks Robert F. Catterson | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| more than 2,000 | approximately 1,000, not including state militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Modern estimates of over 200 killed[1][2] | |||||||

It came at the end of a struggle between white Republican residents in the state before the war, known as scalawags, and newer Republican arrivals called carpetbaggers, over power in state government during Reconstruction after the American Civil War.

The struggle began with the ratification of the 1868 Arkansas constitution, rewritten to allow Arkansas to rejoin the United States after the Civil War. Congress's 1867 Reconstruction Acts required rebel states to accept the 14th Amendment – establishing civil rights for blacks – and enact new constitutions providing suffrage to freedmen (ex-slaves) while temporarily disenfranchising former Confederate Army officers. Some conservatives and democrats refused to participate in the writing of the constitution and ceased participation in government. Republicans and unionists wanting Arkansas to rejoin the United States formed a coalition to write and pass the new constitution, and formed a new state government. In the wake of a wave of reactionary violence by the Ku Klux Klan and a poor economy, the coalition soon fractured into two factions: the "Minstrels",[3] who were mostly carpetbaggers, and the "Brindle Tails",[3] who were mostly scalawags. This led to a failed impeachment trial of the carpetbagger Republican governor, Powell Clayton; he was then elected a U.S. Senator by the General Assembly.

The 1872 gubernatorial election resulted in a narrow victory for Minstrel Elisha Baxter over Brindle Tail Joseph Brooks in an election marked by fraud and intimidation. Brooks challenged the result through legal means, initially without success, but Baxter alienated much of his base by re-enfranchising former Confederates and in 1874, Brooks was declared governor by a county judge who declared the results of the election to have been fraudulent. Brooks took control of the government by force, but Baxter refused to resign. Each side was supported by its own militia of several hundred Black men. Several bloody battles ensued between the two factions. Finally, President Ulysses S. Grant reluctantly intervened and supported Governor Baxter, bringing the affair to an end.

The incident, followed by the new Arkansas Constitution of 1874, marked the end to Reconstruction in Arkansas. The conflict significantly weakened the Republican Party in the state as the Democrats took power and controlled the governorship for 90 years.

Background

1868 Constitution

After the Civil War rebel states, including Arkansas, were in disarray. Slavery, key to their economies and social structure, was gone. Northerners, whom Southerners called carpetbaggers, came to the defeated Southern states to work in the rebuilding process. In 1866, Congress grew increasingly disturbed by post-war developments in the rebel states: pre-Civil War elites, including plantation owners and Confederate Army officers, were reelected to government positions, and southern legislatures enacted "Black Codes" limiting the rights of former slaves, and violence against blacks was common. To redress the matter, Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, dissolving rebel state governments and dividing the South into military districts. Rebel states could only be readmitted to the union if they wrote and ratified new constitutions providing civil rights for freedmen, and accepting the 14th Amendment.[4]

In the fall of 1867 Arkansans voted to convene a new constitutional convention and selected delegates, who convened in Little Rock in January 1868. A coalition of native white unionists, freedman, and carpetbagger Republicans prevailed on most critical proposals. Prominent leaders included James Hinds, Joseph Brooks, John McClure, and Powell Clayton. The new constitution required suffrage (the right to vote) for emancipated adult male slaves, now called Freedmen; it reapportioned the legislative districts to reflect the new status of freedmen as citizens, counting them as full members of the population. It conferred broad powers upon the state government, establishing universal public education (for blacks and whites) for the first time, as well as welfare institutions, absent under the previous government, which were needed in the aftermath of the war. The governor was given wide-ranging powers of appointment without legislative approval, including the power to appoint such top state officials as Supreme Court Judges. The governor was also the president of virtually all state organizations, including the board of trustees of the state's newly created Technical University, the board for public printing, and even the railroad commission. It also temporarily disenfranchised former Confederate Army officers and persons who refused to pledge allegiance to the civil and political equality of all men.

The Democratic Party was also in disarray in Arkansas in 1867-68. One unifying principle of the Democrats, however, was white supremacy and resistance to black suffrage. At the January 27, 1868, Democratic State Convention in Little Rock, Democrats announced the avowed purpose of uniting "the opponents of negro suffrage and domination." Some party leaders opposed Reconstruction in favor of continued military rule, which was far from what they wanted, but seemed like a better option than allowing freedmen all the civil rights of white citizens, including the right to vote. The more conservative wings of the party simply showed no interest in the new constitution and remained loyal to the ideas embodied in the Confederacy. During the constitutional convention, Democrats convened their own party convention. Many chose to boycott elections on the grounds that the new constitution was illegal, because it disenfranchised them while giving suffrage to the Freedmen, whom they insisted were an inferior race. They also alienated the Freedmen who were now the largest block of voters in the state, by adopting resolutions against them: their first resolution of the convention was "Resolved, that we are in favor of a White Man's Government in a White Man's country."[5] Only about ½ of the registered voters in the state cast ballots in the April 1868 elections, and ⅔ of those who voted approved the new constitution.[4]

Clayton Administration

Powell Clayton, a 35-year-old former Brigadier General in the Union Army who remained in Arkansas after marrying an Arkansas woman, was elected governor as a Republican in April, 1868. The election was scarred with irregularities. For example, the return of votes in Pulaski County exceeded the number of registered voters. Also, the registrars, who controlled the distribution of ballots, admitted that they had given ballots to voters from other counties if they could show a valid registration certificate. Both sides claimed election fraud and voter intimidation: armed parties had been stationed on roads to keep voters away from the polls. General Gillem, commander of the military district that included Arkansas, wrote to General Grant that it would take months to sort out which side had committed the greater election fraud.[4]

In July 1868, Arkansas rejoined the union and Clayton was inaugurated governor. The new general assembly had already begun meeting in April, but had been unable to do anything other than prepare legislation for the time when the state was readmitted. The prior governor, Isaac Murphy, whose administration was not recognized by the Federal Government, continued to act as executive of the state during this time. Both Clayton and Murphy managed to draw a paycheck as governor at the same time.[4] When Clayton took office, he appointed most of the key Republican politicians to positions within the new state government; however, he failed to find a place for Joseph Brooks.[6]

Rivalry between Brooks and Clayton predated the 1868 election. Clayton saw Brooks as his strongest competitor for preference and distinction and did not want him to become too entrenched with the party leadership. Brooks felt that his ability and service to the party were not being recognized or appreciated, and he grew bitter and resentful of the other Republicans, including Clayton.[7]

The Democrats in the state, calling themselves "the Conservatives" to differentiate themselves from the Radical Republicans, were incensed that freedmen – former slaves – had been not only emancipated, but cloaked with the status of citizens, with full civil rights, by the 14th Amendment. Worst of all, in the view of Conservatives, freedmen were permitted to vote. Even though the Freedmen, whom Conservatives considered inherently inferior, were allowed to vote, former Confederate officers were not. This was especially infuriating since they were expected to pay taxes to fund newly proposed infrastructure changes without any ability to vote against it.[4] They even saw this as an attempt by the Radicals to circumvent the will of God.[6]

Violence soon erupted throughout the state. Former Confederate Army officers in nearby Memphis, Tennessee, formed the Ku Klux Klan to fight against the new order. The Klan quickly spread into Arkansas. Republican officials, including Congressmen James Hinds, were attacked, as were black citizens seeking to exercise their new civil rights. Hinds and Brooks were ambushed by gunmen on the road in Monroe County, while traveling to a political event. Brooks was severely wounded and Hinds was killed. Hinds was the first sitting member of congress to ever be murdered, and his murder created national disgust for the ongoing political violence in the South. A Coroner's Inquest identified a local Democratic official and suspected Klan member as the killer. Most contemporaries blamed the Ku Klux Klan, which had threatened to kill Hinds and was actively killing and assaulting other Republicans. Reflecting the times, no-one was ever arrested for the murder.[8] As more violence spread throughout the state, Clayton declared martial law in 14 counties.[9]

Many Democratic newspapers denied the existence of the secretive Ku Klux Klan while still reporting on the violence. 20th-century research shows the Klan was responsible for most of the violence in the state at this time. A state militia was organized to put down the violence, although it was poorly equipped. With no uniforms and irregular weapons and mounts, the militia was often mistaken for wandering bands of plunderers, sparking a brief but long-remembered "Militia War", and causing terror throughout the state.[4] This was similar to what was going on in North Carolina at the same time now referred to as the Kirk-Holden war.

Fearing he could not guarantee the integrity of the polling places, Clayton canceled fall elections in counties where political violence had broken out. In doing so, however, he further reduced the Democratic vote, and the state ended up supporting the election of President Grant, the Republican candidate, despite the population being mostly Democratic.[10]

Paying for the new infrastructure

Clayton used various tactics to pay for the needed infrastructure changes in the state. Most of the South was in desperate need of infrastructure and was behind the rest of the country in this respect. He raised taxes, tried to fix the state's bad credit by repaying and issuing bonds, and flooded the state with paper scrip. All of these tactics failed and drove up the state debt.

Introducing more taxes proved to be hugely unpopular among both Democrats and Republicans, and the people of the state simply did not have that much money to give.[4] Bond issues generated controversy and were the source of scandals in the administration. All of the old railroad and infrastructure bonds, including the controversial Holford bonds which had already been declared illegal by the Arkansas Supreme Court, were gathered into a funding act and passed by the legislature.[11] Many bonds were issued for roads and railroads that were never built, or were constructed and then torn up and rebuilt in another direction. Some projects even received the same amount of funding from different bonds, such as embankments built for railroads where roads were funded to be built by a different bond.[11] One of the most controversial bonds involved the purchase of slate for a state penitentiary roof, which was diverted for the construction of a mansion of a Republican official J.L. Hodges, who eventually served jail time for the incident. Promissory notes, or scrip, were issued to raise money. The money was used for construction projects, and invested in public infrastructure. Article VI, Sec 10 of the new constitution stated that the credit of the state could not be loaned without the consent of the voters, making these promissory notes illegal. Their introduction also caused actual currency to go out of circulation.[6]

The Radical Republicans did create some improvement within the state. Levees were constructed and railroads were built. Also, Arkansas' first public school system was created. The administration and its supporters formed the Arkansas Industrial University, the basis for the future University of Arkansas in Fayetteville; what would become the Arkansas School for the Deaf; and the Arkansas School for the Blind, which relocated from Arkadelphia to Little Rock.[9] However, state debt increased dramatically. The state had a budget surplus when Clayton came to office, but by the end of his term, the state debt had increased to $5 million.[4]

Minstrels and Brindle Tails

The "scalawag" native conservative Republicans and the "carpetbagger" migrant radical Republicans had managed to form a coalition to seize complete control of the state in 1868. However, once they had power, the extravagant spending of the carpetbaggers proved to be a wedge issue between the two groups, and factions developed within the party. There was especially strong opposition to the questionable financial maneuvers of the Clayton administration. Despite conciliatory tactics in 1869, the Arkansas Republican Party publicly split in two as scalawags began denouncing the carpetbaggers' reckless spending.[6]

The scalawags met in convention and adopted the name the "Liberal Republicans" and a populist platform for universal amnesty, universal suffrage, economic reforms, and an end to the so-called Clayton dictatorship.[4] A small group of Claytonites, disgruntled with the extravagance of the administration, also defected to this group. Among them was Joseph Brooks, who claimed to be the originator of Radicalism in Arkansas and became their natural leader. Brooks was a Northern Methodist preacher and had been a chaplain for the Union Army. He was known for his fiery speeches that united political and religious themes. He had been the chairman of the 1868 Republican state convention and was at the time the State Senator from White County and Pulaski County. Although he had been involved with the carpetbaggers since the beginning, Clayton had not given him a government position, seeing Brooks as a potential rival.[4]

The Claytonites started calling the new faction "the Brindle Tails". This name can be traced back to Clayton supporter Jack Agery, who was a Freedman, contractor, and orator in the state. In a speech he gave in Eagle Township in Pulaski County, he said that Brooks reminded him of a "brindle tailed bull" he had known as a child that scared all the other cattle.[7] The Claytonist then began mockingly referring to Joseph Brooks and his supporters as "Brindle Tails", and this is how they were referred to from then on. The Brindle Tails' platform included a proposal for a new constitution that would re-enfranchise ex-Confederates, which appealed to Democrats and pre-war Whigs. They began gaining support among the disenfranchised and the Liberal Republicans.[4]

For their part, the Brindle Tails mockingly referred to the Carpetbaggers and Claytonist Republicans as "the Minstrels", and that name stuck as well. This moniker can probably be traced to John G. Price, the editor of the Little Rock Republican and a staunch Clayton supporter. Price was known to be a good musician and comedian and had even once filled in for a sick performer in a minstrel show, complete with blackface.[7]

The Brindle Tails desperately wanted Clayton out of the governor's office. Conveniently, Lieutenant Governor James M. Johnson was a Brindle Tail, so the natural course of action was to try to get rid of Clayton and let Johnson succeed him. Clayton was well aware of their plans, and when he left the state briefly for New York on business concerning the Holford Bonds, he informed no one. When Johnson, who was at home some distance from the capital, found out he tried to head to the capital to take control and have Clayton arrested and impeached. He arrived too late. Subsequently, after Johnson made a speech demanding changes in the administration, the Minstrels started to target Johnson. On January 30, 1871, they introduced articles of impeachment in the General Assembly against him. The chief charge was that Johnson, acting as the President of the Senate, had administered the oath of office to Joseph Brooks, who had recently been elected as state senator, and then recognized him on the floor. Although this was legitimately within his powers as the lieutenant governor to do, he escaped impeachment by only two votes. The scrutiny of the proceedings seriously damaged his reputation, even though he had done nothing wrong, and his political career never recovered.[4]

In 1871, Clayton was accused of deliberately tampering with the results of the U.S. house election between Thomas Boles and John Edwards in the third congressional district. According to Arkansas law, the results were to be certified and given to the secretary of state, then Robert J.T. White. After that, the governor and secretary of state would "take up and arrange" the results and the governor would issue a proclamation declaring the winner and deliver the seal of the state to him. Clayton was accused of adding around a hundred votes to the final count for Edwards, and declaring him the winner. Boles successfully contested the election and Clayton was indicted by the federal Circuit Court. Although the court found that Clayton did in fact falsify his proclamation and delivered the seal to Edwards knowing full well that he had not won, this was not illegal. His actions were in no way binding to the Congress and under federal law of the time, state governors were not considered election officials. Boles became a congressman.[12]

To sequester Clayton from the affairs in the state, the Brindles and the Democrats decided the only thing they could do was elect him to the US Senate. However, even though he won unanimously, he refused to take his seat, which would mean letting Johnson become governor. In 1871, the state House of Representatives drafted articles of impeachment against Clayton, charging him with a wide variety of impeachable actions, including depriving Johnson and several other state officials of offices to which they had been fairly elected, removing state officials and judges from offices to which they had been fairly elected, aiding in fraudulent elections, taking bribes for state railroad bonds, and various other high crimes and misdemeanors. The members of the House then tried to suspend Clayton from his duties as governor by force. They even apparently tried locking him in his office and nailing the door shut. However, Clayton responded that they had no right by the state constitution to deprive him of his office. At the same time, the House also brought impeachment charges against Chief Justice John McClure for his part in trying to deny Johnson the privileges of his office of lieutenant governor.[13]

Two successive inquiries failed to find evidence against Clayton. The legislature refused to continue, all charges were dropped, and Clayton was exonerated. In fact, he was never found guilty of any wrongdoing while governor. Finally a deal was reached. Johnson, now politically badly damaged by his impeachment ordeal and willing to take any position he could get, resigned as lieutenant governor, was appointed Secretary of State, and was given a compensation of several thousand dollars for his loss of power and prestige, since he would not become governor. A staunch Clayton supporter, O.A. Hadley, was then appointed lieutenant governor. Three days later, Clayton left the state for Washington, D.C., to join the US Senate, and Hadley succeeded him as governor.[4]

The Democrats' paper, the Arkansas Daily Gazette crowed:

It will be a source of infinite joy and satisfaction, to the oppressed and long suffering people of Arkansas, to learn that, on yesterday, the tyrant, despot and usurper, late of Kansas, but more recently, governor of Arkansas, took his departure from the city and his hateful presence out of our state, it is to be hoped, forever and ever.[14]

Although no longer a state official, Clayton remained the leader of the state Republicans and was controlling now not only appointments within the state, but also the flow of federal money and positions. He began purging Brindles from federal office, including Joseph Brooks, who was at this point an Internal Revenue Assessor.[4]

Election of 1872

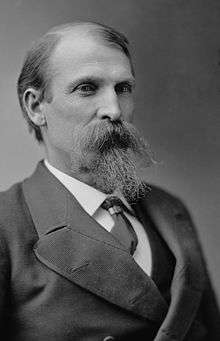

Brooks and Baxter

In the gubernatorial election of 1872, the Minstrels faction nominated Elisha Baxter as their candidate. Baxter was a lawyer, politician, and merchant from North Carolina who had settled in Batesville, and a life long Whig. He was elected Mayor of Batesville in 1853 and elected to the state legislature in 1858. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he had been conflicted about which side he supported. When General Samuel Curtis and the 2nd Iowa Infantry occupied Batesville in the Spring of 1862, the General recognized Baxter as a loyal Unionist, and tried to bestow upon him the title of "Regt. of loyal Arkansians" which he refused. When Curtis left Batesville, Baxter was forced to flee to Missouri. He was captured, brought back to Little Rock, and charged with treason, only to escape later before his trial could take place.[15] He describes this episode in his life in his autobiography:

Through a fortunate combination of circumstances I escaped from prison before my trial came on and lived for eighteen days in the forist(sic) and fields near Little Rock without a morsil(sic) of food except such raw corn and berries as I could gather in my lone wanderings. While a prisoner I felt that I was ungenerously treated by the harsh criticisms of the press and individuals not only in regard to my want of loyalty to the southern caus(sic) but also with regard to my supposed want of courage. I therefore resolved if God would grant me deliverance I would at once enter the Federal Army.[15]

When Baxter returned to Batesville, he organized the 4th Arkansas Mounted Infantry for the Union and commanded it until he was named a State Supreme Court judge by Governor Murphy in the Spring 1864. Shortly after being named a judge, he was elected to the U.S. Senate by the legislature along with Rev. Andrew Hunter, but they were not seated in the Senate as the senate did not recognize the Murphy Administration. In 1867, he was appointed by Governor Clayton judge of the 3rd Judicial circuit. In 1868 he was appointed the 1st Congressional district of Arkansas. He held these two positions until he was nominated for governor in 1872.[15] Baxter was virtually unknown and privately clean of scandals, unlike most of the Minstrels. They believed he could attract votes from Unionists and Northerners, their core base, as well as natives of the state.[4]

Joseph Brooks ran for governor representing the Brindle Tails. Brooks was a very vocal supporter of civil rights for former slaves, but also a supporter of re-enfranchisement for ex-Confederates, which was the sentiment nationally of Liberal Republicans.[16] When the Democrats met, they agreed not only to not run a candidate, but even to support Joseph Brooks, as long as the election was fair and legal, since elections in the state had been wrought with fraud for five years. The issue of re-enfranchisement of Confederates was central to the election.[17]

The outcome

The election of 1872 has been described as a "masterpiece of confusion" by Arkansas historian Michael B. Dougan. "That carpetbagger Brooks ran with Democratic support against a scalawag nominated by a party composed almost exclusively of carpetbaggers was enough to bewilder most voters as well as the modern student."[16]

In the days before the election and the days afterward, predictions and reports of fraud were printed daily in the Gazette. Because of the relatively slow communications, messages from other counties were often delayed up to a week. There were numerous reports of anomalies in state polling centers, including names being inexplicably stricken from the voter registration lists and persons voting without proof of registration. The Gazette wrote:

It would be as great a farce of yesterday's election to designate it otherwise than a fraud. It was one of the worst ever yet perpetrated in the state. The city judges paid no attention to any registration either old or new, but permitted everybody to vote, and in many instances without question. Men were marched from one ward to another and voted early and often.[18]

On November 6, 1872, the day after the general election, the Gazette reported: "The election was one of the most quiet in Little Rock we ever witnessed.[19] The returns on that day were too small to report with any certainty who had won, and the newspaper reported fraud. Rumors flew about claiming that registration had been cut short or extended in many counties to suit the needs of whoever controlled the polling places. The following Monday, the Gazette published incomplete tallies from the various counties, showing a small majority for Baxter. They also reported more forms of attempted fraud. Some unofficial polling places had apparently been set up, but only those votes cast at the regular polls had been certified.[20]

By November 15, the Gazette claimed victory for Brooks.[18] By the next day, because of the irregularities and votes that would be thrown out, the projected winner was Baxter, by only 3,000 votes.[20] The General Assembly met on January 6 for a special joint session to declare Baxter, who by their count had received the most votes, the legal winner of the election. After a short address he was sworn in by Chief Justice John McClure.[17] He then assumed the duties of Governor of the State of Arkansas.

Brooks supporters immediately claimed that the election had been dishonest. The Democrats, the Brindle Tails, and all non-Republican newspapers openly and vocally denounced the election as fraudulent, and insisted that Brooks had in fact received the most votes. The general citizenry of both parties, however, accepted the results. The Brooks supporters were in the minority in believing that the election had been fraudulent.[17]

Brooks's legal battle

The first to file suit over the election was Judge William M. Harrison, who had been on the Brooks ticket. He filed a Bill of Equity with the US Circuit Court in Little Rock, claiming he had a right to a seat on the Supreme Court due to the fraudulent election. The Brooks Campaign likewise filed suit in the Circuit Court shortly thereafter on January 7, 1873. Judge H.C. Caldwell heard the Harrison case, and rendered an opinion stating that the Federal Court had no jurisdiction in the matter, and dismissed the case. The Harrison decision resulted in the dismissal of the Brooks case as well.[17]

Brooks then took a petition to the General Assembly, asking for a recount. The assembly took up the matter on April 20, 1873 and voted 63 to 9 not to allow Brooks to contest the election.[17] This did not deter Brooks, and he applied to the Arkansas Supreme Court for a writ of quo warranto, and was again denied. They also ruled that state courts had no jurisdiction in the matter, and dismissed the case. They gave a lengthy explanation as to why the General Assembly should decide contested gubernatorial elections in Joint Session, since they are the directly elected representatives of the people.[21]

It appeared that Brooks had exhausted all legal avenues at this point, but on June 16, 1873, he filed another lawsuit against Baxter, this time with the Pulaski County district court. Under Arkansas Civil Code sec. 525, if a person usurps an office or franchise to which he is not entitled, an action at law may be instituted against him either by the State or by the party rightly entitled to the office. On October 8, 1873, Baxter filed a plea of non-jurisdiction, but he believed that the court might decide against him. He issued a telegram to President Grant informing him of the basic situation in Arkansas and asked for federal troops to help him maintain the peace. Grant denied his request.[22]

Baxter and Brooks switch positions

There were rumors that Joseph McClure, the Chief Justice who had sworn him into office, intended to have Baxter either arrested or killed, ostensibly because Baxter had replaced W. W. Wilshire, a Minstrel, with Robert C. Newton, an ex-Confederate, as head of the state militia. U.S. Attorney General Williams contacted Baxter and suggested that he ask for federal troops for protection again. A letter from President Grant followed, offering protection. The Grant administration usually followed Powell Clayton's lead where Arkansas matters were concerned, so it can be concluded that the former governor was still supporting Baxter.[23] The Republican Party of Arkansas, still controlled by the Minstrel faction, issued a statement denouncing Brooks' attempt to contest the election, which was published in the Little Rock Republican on October 8, 1873 and signed by all the major members of the party, including Clayton.[17] However, the Minstrels would soon turn on Baxter for not following the party line.

Baxter had now been governor for a year and was following an independent course. He began dismantling the systems put in place by the Minstrels. He appointed honest Democrats and Republicans to the Election Commission, reorganized the militia by placing it under the control of the State, rather than the governor, and pushed for an amendment to the state constitution to re-enfranchise ex-Confederates.[24]

On March 3, 1873, the state legislature passed a bill re-enfranchising ex-Confederates, to the delight of much of the state population and the concern of the Minstrels. The legislature called a special election in November to replace 33 members, mostly Minstrels, who had left for patronage jobs in the Baxter government. Baxter refused to let the Minstrels manipulate the election, declaring that free, honest elections would be held during his term.[17] With the help of the newly re-enfranchised voters, conservative Democrats swept the election and gained a small majority in the legislature.[24] Baxter was about to erode his Republican base out from under him.

In March 1874, Baxter vetoed the Railroad Steel Bill, the centerpiece of the Radical Republican Reconstruction plan. The bill would have released the railroad companies from their debts to the state and created a tax to pay the interest on the bonds.[25] This was clearly not legal and the veto called into question the legality of the 1868 railroad bonds, which created a public bonded debt.[16] It is likely the Minstrels struck a deal with Brooks to support the railroad bonds, and within a month the political backers of Brooks and Baxter began to switch. Senator Clayton issued a statement saying that "Brooks was fairly elected in 1872; and kept out of office by fraud."[4] Governor Baxter was now being supported by the Brindle Tails, re-enfranchisers, and the Democrats; whereas Brooks was finding support among the Claytonists, Northerners, Unionists, the Minstrel Republicans.

Brooks was assigned three prominent Minstrel attorneys, and after a year of sitting on the docket, at about 11 AM on April 15, 1874, Baxter's demurrer to Brook's complaint was suddenly called up. Neither of Baxter's lawyers were present in the court room, and the demurrer had been submitted without their knowledge. Without giving Baxter any time to testify, Judge Whytock overruled the demurrer and awarded Brooks $2,000 in damages and the office of Governor of Arkansas. Neither Brooks nor the court notified the legislature or Governor Baxter. Judge Wytock then swore in Joseph Brooks as the new governor of Arkansas, despite having no authority to do so.[17][24]

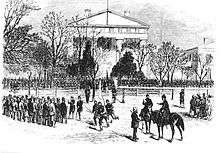

Brooks' seizure of power

With the aid of General Robert F. Catterson and state militia, Brooks, accompanied by about 20 armed men, marched to the Arkansas Capitol building (now known as "the Old Statehouse"), located at Markham and Center streets in downtown Little Rock. They ordered Baxter to abdicate his office, but Baxter refused to do so unless physically forced. The mob obliged and dragged Baxter out of the Capitol building and onto the street.[16]

By the end of the afternoon, nearly 300 armed men had converged on the lawn of the State Capitol. Brooks' men seized the state arsenal and began turning the Statehouse into an armed camp. Telegrams covered in signatures were sent to President Ulysses S. Grant supporting Brooks as the legal governor. Three out of the five Supreme Court justices also telegraphed the President in support of Brooks. Brooks telegraphed the President himself asking for access to weapons housed at the federal arsenal. He also issued a statement to the press proclaiming himself governor. The senators from the state, Clayton and Steven Dorsey, met with President Grant, and they sent a message to Brooks giving their support.[24]

Unusually for someone physically removed from power, Baxter was allowed to remain free in Pulaski County. He first retired to the Anthony House, three blocks away from the State Capitol. Ads placed in the Gazette indicate that the Anthony House continued to function as an upscale hotel during the entirety of the crisis. Fighting occurred outside the hotel, and at least one man, David Fulton Shall, a prominent real estate dealer, was shot dead while standing in a window of the building.[7]

Baxter then moved his headquarters to St. Johns College, a Masonic institution on the southeastern edge of the state. Baxter issued two proclamations to the press from his temporary office, asserting his rights to the governorship by vote of the people and the decision of the legislature; both were printed in the Gazette. He received support from many prominent Democrats in the city, all of whom had initially voted for Brooks. He then issued a dispatch to President Grant explaining the situation, calling Brooks and his band "revolutionaries", and stating that he would do everything up to and including armed conflict to regain control of the state organs. He asked for the support of the Federal Government.[17]

Brooks issued a proclamation to the people of Arkansas asking them for their support. Baxter answered with proclamation to the people of Arkansas declaring martial law in Pulaski County. A company was then issued from the young men of Little Rock. On the evening of April 16, the assembled army, now being referred to as the "Hallie Riflers", escorted Baxter back to the Anthony House, where he set up his headquarters, and from there he began trying to do the state's business once more.[4]

There were now two militias marching and singing through Little Rock as the city became a battle ground. Commanding both forces were ex-Confederate soldiers. Former Brigadier General James F. Fagan commanded the Brooks men, and Robert C. Newton, a former Colonel, commanded the Hallie Riflers, or Baxter's forces. Baxter's men occupied the downstairs billiards area of the Anthony House, and patrolled the cross streets outside. Down the street, the Brooks men patrolled the front of the state house. The front line was Main Street. The post-master handled the situation by only delivering mail addressed to Brooks or Baxter, and holding all mail simply addressed to "Governor of Arkansas." [26]

The Lady Baxter, a cannon on permanent display in front of the Old State House, is the most prominent artifact remaining from the Brook-Baxter war. The cannon is a Confederate copy of a United States Model 1848 64-pounder siege gun 8 in (200 mm) Naval columbiad, designed to fire explosive shells. Originally from a foundry in New Orleans, it was brought to Arkansas in the summer of 1862 by the steamboat "Ponchatrain", and saw action on the Mississippi, White, and Arkansas rivers, until it was transferred to Fort Hindman at Arkansas Post. Union forces captured the fort in 1863 but left the cannon behind. It was then brought to Little Rock by Confederates and placed on Hanger Hill overlooking the river to ward off any ships coming up stream, but in this position at least it was never fired. Little Rock was captured in September 1863. Confederates tried to burst the cannon and then, failing that, drove a nail into the touch hole and abandoned it on the shore. It sat there half embedded in the ground until 1874. The Baxter men pulled the cannon out of the soil, repaired it, rechristened it the "Lady Baxter", and made it ready to fire. It was placed in the rear of the Odd Fellows hall, now the Metropolitan Hotel, on the corner of Main and Markham streets to hit any boats bringing supplies for Brooks up the river. The cannon however was only fired once, a celebratory blast, when Baxter finally returned to the governor's seat. The war's final casualty was the result of the cannon firing, as the operator was badly injured. It has since been in its current place on brick pedestals in front of the then-state capitol, only briefly threatened by World War II scrap drives.[27][28][29][30][31][32]

Overtones of the Civil War and racial conflict were evident. Brooks' men numbered 600 by this time, and were all freedmen who supported Republicans as their emancipators. Baxter's forces, all white Democrats, continued to grow steadily during the conflict until they reached nearly 2,000.[24] Several bloody skirmishes occurred. Known as the Battle of Palarm, a small naval battle erupted on the Arkansas River near Natural Steps, where Brooks' men attacked a flatboat known as the "Hallie", thought to be bringing supplies. The shooting lasted around ten to fifteen minutes before the pilot ran up a white flag signaling a surrender. One stray bullet pierced the vessel's supply pipe between the boiler and engine, cutting off its power, and the boat drifted downriver, out of gun range, and lodged on the Southern (Western) shore. Sources vary as to the actual casualties of the incident. The boat's captain, a pilot, and one rifleman were killed; the other pilot and three or four riflemen were wounded. One source stated that the Brooks regiment suffered one man killed and three wounded; another report was that five men were killed and "quite a number" wounded.[33]

Casualty reports vary widely depending on the source; the New York Times of May 30, 1874, gave the following for casualties and fatalities:

| Army | Killed | Wounded |

|---|---|---|

| Baxter militia | 8 | 13 |

| Brooks militia | "about 30" | "upwards of 40" |

Brooks loses favor

On May 3, men claiming to be acting on behalf of Baxter supporters hijacked a train from Memphis, Tennessee, and arrested federal Court Justices John E. Bennett and Elhanan John Searle, thinking that the Court would be unable to rule without a quorum of Judges. Baxter denied that they were acting under his direction. The Judges were taken to Benton, Arkansas. For several days, their whereabouts were unknown to the public and federal officials began a search for the Justices. Justice Bennett was able to send a letter to Captain Rose demanding to know why they were being held by the Governor of Arkansas. Upon receipt of the letter, troops were sent to Benton to retrieve the two Justices, but they had escaped by May 6 and made their way to Little Rock.[16][34]

In Washington, Brooks was supported politically, but Baxter also had support because of the undemocratic way he had been removed from office. President Grant had already dealt with the outcome of the contested election for Governor of Louisiana, the Colfax massacre, where federal troops had to be sent to restore order. As Brooks and Baxter scrambled for support in Washington, D.C., Grant pushed for the dispute to be settled in Arkansas. Baxter demanded the General Assembly be called into session. He knew he had their support, but so did Brooks, so he and his men would not allow anyone to enter the capitol building. Brooks, on the other hand, had the support of the district court.[24] He enlisted Little Rock's premiere lawyer, U. M. Rose, head of the still-prominent Rose Law Firm.[16] However, Grant's decision would soon set in motion the demise of Brooks' governorship.

It was becoming clear that federal intervention was required to settle the dispute, despite the general policy of the Grant administration to stay out of the affairs of Southern states. The President often expressed annoyance with Southern governors who requested help from federal troops to combat regular waves of election year violence, with little compassion for the issues they faced. Grant and the United States Attorney General, George Henry Williams, issued a joint communique supporting Baxter and ordering Brooks to vacate the capitol. They also referred the dispute back to the State Legislature.[23][35]

Historian Allan Nevins believes Grant had been hoodwinked. When Baxter refused to sign two million dollars' worth of fraudulent railroad bonds, Boss Shepherd and Senator Dorsey turned against him and convinced Grant to do the same.

- President Grant on May 15, 1874, had declared Baxter to be governor, denouncing Brooks and his party; now on February 8, 1875, he declared that Brooks had been elected and denounced Baxter and his followers! Senator Dorsey, later a principal in the Star Route frauds, was a neighbor and close friend of Boss Shepherd's, living in a house owned by him.... "I believe," commented [Secretary of State] Fish, "that there is a large steal in the Arkansas matter, and fear that the President has been led into a grievous error."[36]

On May 11, Governor Baxter asked the General Assembly to meet in special session, which they did. Apparently, they met "behind Baxter lines" although where that was isn't exactly clear. Since the Speaker of the House and President pro tempore of the Senate were both absent, being that they were both Brooks supporters, they were replaced. J.G. Frierson was elected President pro tempore of the Senate and James H. Berry Speaker of the House. They then passed an act calling for a constitutional convention, which Governor Baxter approved on May 18. The act scheduled an election for the last day of June and appointed delegates from the counties of Arkansas.[27] Two days later, Generals Newton and Fagan negotiated an armistice. At the same time, the Arkansas Supreme Court had finally decided to hear the Brooks case, and voted three to one in favor of Baxter's election, further solidifying the Grant proclamation and Baxter as governor.[23] The bar of the Pulaski County Circuit court also met and issued a resolution that stated that Judge Wytock had acted independently, and his decision did not represent the court. The trial had been deliberately unfair for the defendant Baxter, and the Supreme Court had already ruled that, under the state constitution, the court had no jurisdiction. They rendered Judge Wytock's decision null and void.[4]

On May 19, General Newton and his troops reoccupied the State House grounds, which had just been evacuated by Brooks' forces, and on the 20th, he reinstated Governor Baxter.[37]

Aftermath

In June 1874, Clayton announced that he could no longer control matters in Arkansas and that he and his friends would be willing to enter into any arrangement whereby they could at least be safe from persecution and prosecution. However, the Democrats retaliated by impeaching many Minstrels, including Supreme Court Justice John McClure. Clayton finished his Senate term but was not re-elected.[4]

On September 7, 1874, the new constitution was completed and signed by a majority of delegates. The entire electorate, including the disenfranchised Confederates and the Freedmen, voted. The election not only was for ratification of the new constitution but also for state officials that would be elected if the constitution was indeed ratified. The Republicans actually took the same position that the Democrats had taken earlier, believing that the election was illegal they nominated no candidates.[27] Conservative Democrats and allied paramilitary groups suppressed black voting, using a combination of intimidation, blocking blacks from the polls, and outright assassinations. The new constitution was ratified on October 13, 1874 and Democratic officials elected almost unanimously, including new Democratic Governor Augustus H. Garland who was inaugurated November 12, 1874, and Baxter left office after only serving two years of a four-year term.[4]

It was a long time after the Brooks–Baxter War that people of Arkansas allowed another Republican to become governor. The following 35 governors of Arkansas, ruling for a total of 90 years, were all Democrats, until Republican Winthrop Rockefeller became governor in 1966 defeating James D. Johnson.[38] Winthrop became governor while his brother Nelson was governor of New York, while the defeat of Johnson in Arkansas and William M. Rainach in Louisiana ended the once mighty hold of segregation over politics.

References

- Old State House history Archived 2015-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "Brooks-Baxter War - Encyclopedia of Arkansas". www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net.

- Johnson, Nicholas (2014). Negroes and The Gun: the black tradition of arms. Amherst, New York: Prometheus. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-61614-839-3.

- Driggs, Orval Truman, Jr. (1947). The issues of the Clayton regime (1868-1871). (Thesis: M.A.).

- Joseph Starr Dunham ed. Van Buren Press. Van Buren, Arkansas. Joseph Starr Dunham, ed. (February 18, 1868). "Van Buren Press February 18, 1868". Van Buren Press. Van Buren.

- Harrell, John (1893). The Brooks and Baxter War. St. Louis, Missouri: Slawson Printing Company. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- House, Joseph W. (1917). "Constitutional Convention of 1874 – Reminiscences". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Arkansas Historical Association. 4: 210–268. Retrieved July 19, 2009.

- Marion, Nancy E.; Oliver, Willard M. (2014). Killing Congress: Assassinations, Attempted Assassinations and Other Violence Against Members of Congress. Lexington Books. pp. 8–12. ISBN 9780739183595.

- Moneyhon, Carl H. "Powell Clayton (1833–1914)". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- Old Statehouse Museum. Little Rock, Arkansas ([?2009]). Powell Clayton: Martial Law and Machiavelli Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine. In Exhibition: Biographies of Arkansas's Governors online Archived 2010-07-11 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- Lafayette, Franklin (1909). The South in the building of the nation. Richmond Virginia: The Southern Historical publication Society. pp. 322–330. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Green, Nicholas (1876). Criminal Law Reports. Cambridge, England: Hurd and Houghton. pp. 434–439. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Foster, Roger (1895). Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston Book Company. pp. 685–688. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- The Daily Arkansas Gazette. Little Rock, Arkansas. #101. March 19, 1871.

- Worley, Ted R. (Summer 1955). "Elisha Baxter's Autobiography". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 14 (2): 172–175. doi:10.2307/40025473. JSTOR 40025473.

- Zuczek, Richard (2006). Encyclopedia of the Reconstruction Era. Westport: Greenwood Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 0-313-33073-5.

- Johnson, Benjamin S. (1908). "The Brooks–Baxter War". The Arkansas Historical Association. 2: 122–173. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- The Daily Arkansas Gazette. Little Rock, Arkansas. #299. November 15, 1872

- The Daily Arkansas Gazette. Little Rock, Arkansas. #291. November 7, 1872

- The Daily Arkansas Gazette. Little Rock, Arkansas. #300. November 16, 1872

- The Daily Arkansas Gazette #837. Little Rock, Arkansas. April 29, 1874

- Corbin, Henry (1903). Federal Aid in Domestic Disturbances 1787–1903. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 164–181. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- Old Statehouse Museum. Little Rock, Arkansas ([?2009]). Elisha Baxter: Reconstruction Unravels Archived 2011-06-11 at the Wayback Machine. In Exhibition: Biographies of Arkansas's Governors online Archived 2010-07-11 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- Owings, Robert ([?2009]). The Brooks-Baxter War Archived May 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Little Rock, Arkansas: Old State House Museum. Reprint of Owings, Robert. "The Brooks-Baxter War" The Arkansas Times. [?1998].

- Shinn, Josiah (1903). History of Arkansas. Little Rock, Arkansas: Wilson and Webb Book and Stationery Company. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- Dougan, Michael B. (1994). Arkansas Odyssey: The Saga of Arkansas from Prehistoric Times to Present: A History. Little Rock, Arkansas: Rose Publishing Company (Ar). pp. 259–264.

- Herndon, Dallas (1922). Centennial History of Arkansas. Easley, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press. pp. 307–314. ISBN 978-0-89308-068-6. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- "The poet laureate of Freemasonry". arkansasonline.com. 11 February 2018.

- "Military Relics Disappearing Faster Than Decorum". 2018-07-14. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- "Bull and Bottaken." Arkansas Daily Gazette, May 30, 1874, p. 4.

- "Items in Brief." Arkansas Daily Gazette, May 17, 1874, p. 4.

- Sherwood, Diana. "Shall 'Lady Baxter' Be Junked?" Arkansas Gazette Magazine, October 4, 1942, pp. 9, 15.

- Meriwether, Robert W. (Fall–Winter 1995). "The Battle at Palarm". Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings (Volume XXXVII, Nos. 3–4 ed.). Faulkner County Historical Society: 70–73. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "Correspondence, Assistant Justice". The American annual cyclopedia and register of important events. 14. D. Appleton & Co. 1875. p. 43.

- John, Reynolds (1917). "Western Boundary of Arkansas". Publications of the Arkansas Historical Association. Arkansas Historical Association. 2: 227.

- Allan Nevins, Hamilton Fish: The Inner History of the Grant Administration (1936) Vol. 2 p 758-59

- Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1888). "John Thomas Newton". Appleton's cyclopædia of American biography. D Appleton Co. p. 509.

- "Arkansas: Squealing at the Lick Log". Time. 1966-11-04.

Bibliography

- American Annual Cyclopedia...for 1873 (1879) pp 34–36 online

- Atkinson, James H. "The Brooks-Baxter Contest", Arkansas Historical Quarterly 4 (1945): 124-49.in JSTOR

- Corbin, Henry (1903). Federal Aid in Domestic Disturbances 1787–1903. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 164–181. ProQuest 301856914.

- DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword, Arkansas, 1861-1874 (University of Arkansas Press, 2003)

- Driggs, Orval Truman, Jr. (1947). The issues of the Clayton regime (1868-1871) (M.A. thesis). University of Arkansas. ProQuest 301856914.

- Gillette, William. Retreat from Reconstruction, 1869-1879 (LSU Press, 1982). pp 146–50.

- Harrell, John (1893). The Brooks and Baxter War. St. Louis, Missouri: Slawson Printing Company.

- House, Joseph W. (1917). "Constitutional convention of 1874 – Reminiscences". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Arkansas Historical Association. 4: 210–268. Retrieved July 19, 2009.

- Johnson, Benjamin S. (1908). "The Brooks—Baxter War". The Arkansas Historical Association. 2: 122–173. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- Kraemer, Michael William. "Divisions Between Arkansans in the Brooks-Baxter War." (U of Kentucky Graduate Thesis, 2012). online

- Meriwether, Robert W. (Fall and Winter, 1995). "Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings" (Volume XXXVII, Nos. 3–4 ed.). Faulkner County Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - Moneyhon, Carl H. "Powell Clayton (1833–1914)" in Encyclopedia of Arkansas online

- Moneyhon, Carl H. "Baxter, Elisha" in American National Biography Online Feb. 2000

- Staples, Thomas S. Reconstruction in Arkansas (New York: Longmans, Green & Co,1923)

- Thompson, George H. Arkansas and Reconstruction: The Influence of Geography, Economics, and Personality (1976),

- Woodward, Earl F. "The Brooks and Baxter War in Arkansas, 1872-1874", Arkansas Historical Quarterly 1971 30(4): 315-336 in JSTOR

- Worley, Ted R. (Summer 1955). "Elisha Baxter's Autobiography". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 14 (2): 172–175. doi:10.2307/40025473. JSTOR 40025473.

- Zuczek, Richard (2006). Encyclopedia of the Reconstruction Era. Westport: Greenwood Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 0-313-33073-5.