Abraham Lincoln in politics, 1849–1861

This article documents the political career of Abraham Lincoln from the end of his term in the United States House of Representatives in March 1849 to the beginning of his first term as President of the United States in March 1861.

| ||

|---|---|---|

President of the United States

First term

Second term

Presidential elections

Assassination and legacy

|

||

After serving a single term in the House of Representatives, Lincoln returned to Springfield, Illinois, where he worked as lawyer. He initially remained a committed member of the Whig Party, but later joined the newly-formed Republican Party after the Whigs collapsed in the wake of the 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act. In 1858, he launched a challenge to Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Though Lincoln failed to unseat Douglas, he earned national notoriety for his role in the Lincoln–Douglas debates. He subsequently sought the Republican presidential nomination in the 1860 presidential election, defeating William Seward and others at the 1860 Republican National Convention. Lincoln went on to win the general election by winning the vast majority of the electoral votes cast by Northern states. In response to his election, several Southern states seceded, and the American Civil War would commence in the second month of Lincoln's presidency.

Background

From the early 1830s, Lincoln was a steadfast Whig and professed to friends in 1861 to be "an old line Whig, a disciple of Henry Clay".[1] The party, including Lincoln, favored economic modernization in banking, protective tariffs to fund internal improvements including railroads, and espoused urbanization as well.[2] Lincoln won election to the House of Representatives in 1846, where he served one two-year term. He was the only Whig in the Illinois delegation, but he showed his party loyalty by participating in almost all votes and making speeches that echoed the party line.[3] Lincoln, in collaboration with abolitionist Congressman Joshua R. Giddings, wrote a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation for the owners, enforcement to capture fugitive slaves, and a popular vote on the matter. He abandoned the bill when it failed to garner sufficient Whig supporters.[4]

Realizing Clay was unlikely to win the presidency, Lincoln, who had pledged in 1846 to serve only one term in the House, supported General Zachary Taylor for the Whig nomination in the 1848 presidential election.[5] Taylor won and Lincoln hoped to be appointed Commissioner of the General Land Office, but that lucrative patronage job went to an Illinois rival, Justin Butterfield, considered by the administration to be a highly skilled lawyer, but in Lincoln's view, an "old fossil".[6] The administration offered him the consolation prize of secretary or governor of the Oregon Territory.[7] This distant territory was a Democratic stronghold, and acceptance of the post would have effectively ended his legal and political career in Illinois, so he declined and resumed his law practice.[8] Lincoln returned to practicing law in Springfield, handling "every kind of business that could come before a prairie lawyer".[9] Twice a year for 16 years, 10 weeks at a time, he appeared in county seats in the midstate region when the county courts were in session.[10]

Emergence as Republican leader

The debate over the status of slavery in the territories exacerbated sectional tensions between the slave-holding South and the North, and the Compromise of 1850 failed to defuse the issue.[11] In the early 1850s, Lincoln supported efforts for sectional mediation, and his 1852 eulogy for Henry Clay focused on the latter's support for gradual emancipation and opposition to "both extremes" on the slavery issue.[12] As the 1850s progressed, the debate over slavery in the Nebraska Territory and Kansas Territory became particularly acrimonious, and Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois proposed popular sovereignty as a compromise measure; the proposal would take the issue of slavery out of the hands of Congress by allowing the electorate of each territory to decide the status of slavery themselves. The proposal alarmed many Northerners, who hoped to stop the spread of slavery into the territories. Despite this Northern opposition, Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act narrowly passed Congress in May 1854.[13]

For months after its passage, Lincoln did not publicly comment on the Kansas–Nebraska Act, but he came to strongly oppose it.[14] On October 16, 1854, in his "Peoria Speech", Lincoln declared his opposition to slavery, which he repeated en route to the presidency.[15] Speaking in his Kentucky accent, with a very powerful voice,[16] he said the Kansas Act had a "declared indifference, but as I must think, a covert real zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world ..."[17] Lincoln's attacks on the Kansas–Nebraska Act marked his return to political life.[18]

Nationally, the Whigs were irreparably split by the Kansas–Nebraska Act and other efforts to compromise on the slavery issue. Reflecting the demise of his party, Lincoln would write in 1855, "I think I am a Whig, but others say there are no Whigs, and that I am an abolitionist [...] I do no more than oppose the extension of slavery."[19] Drawing on the antislavery portion of the Whig Party, and combining Free Soil, Liberty, and antislavery Democratic Party members, the new Republican Party formed as a northern party dedicated to antislavery.[20] Lincoln resisted early attempts to recruit him to the new party, fearing that it would serve as a platform for extreme abolitionists.[21] Lincoln also still hoped to rejuvenate the ailing Whig Party, though he bemoaned his party's growing closeness with the nativist Know Nothing movement.[22]

In the 1854 elections, Lincoln was elected to the Illinois legislature but declined to take his seat.[18] In the aftermath of the elections, which showed the power and popularity of the movement opposed to the Kansas–Nebraska Act, Lincoln instead sought election to the United States Senate.[23] At that time, senators were elected by the state legislature.[24] After leading in the first six rounds of voting, but unable to obtain a majority, Lincoln instructed his backers to vote for Lyman Trumbull. Trumbull was an antislavery Democrat, and had received few votes in the earlier ballots; his supporters, also antislavery Democrats, had vowed not to support any Whig. Lincoln's decision to withdraw enabled his Whig supporters and Trumbull's antislavery Democrats to combine and defeat the mainstream Democratic candidate, Joel Aldrich Matteson.[25]

In part due to the ongoing violent political confrontations in the Kansas, opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act remained strong in Illinois and throughout the North. As the 1856 elections approached, Lincoln abandoned the defunct Whig Party in favor of the Republicans. He attended the May 1856 Bloomington Convention, which formally established the Illinois Republican Party. The convention platform asserted that Congress had the right to regulate slavery in the territories and called for the immediate admission of Kansas as a free state. Lincoln gave the final speech of the convention, in which he endorsed the party platform and called for the preservation of the Union.[26] At the June 1856 Republican National Convention, Lincoln received significant support on the vice presidential ballot, though the party nominated a ticket of John C. Frémont and William Dayton. Lincoln strongly supported the Republican ticket, campaigning for the party throughout Illinois. The Democrats nominated former Ambassador James Buchanan, who had been out of the country since 1853 and thus had avoided the debate over slavery in the territories, while the Know Nothings nominated former Whig President Millard Fillmore.[27] In the 1856 elections, Buchanan defeated both his challengers, but Frémont won several Northern states and Republican William Henry Bissell won election as Governor of Illinois. Though Lincoln did not himself win office, his vigorous campaigning had made him the leading Republican in Illinois.[28]

Eric Foner (2010) contrasts the abolitionists and anti-slavery Radical Republicans of the Northeast who saw slavery as a sin, with the conservative Republicans who thought it was bad because it hurt white people and blocked progress. Foner argues that Lincoln was a moderate in the middle, opposing slavery primarily because it violated the republicanism principles of the Founding Fathers, especially the equality of all men and democratic self-government as expressed in the Declaration of Independence.[29]

In March 1857, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford. The opinion by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney held that blacks were not citizens and derived no rights from the Constitution. While many Democrats hoped that Dred Scott would end the dispute over slavery in the territories, the decision sparked further outrage in the North.[30] Lincoln denounced the decision, alleging it was the product of a conspiracy of Democrats to support the Slave Power.[31] Lincoln argued, "The authors of the Declaration of Independence never intended 'to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity', but they 'did consider all men created equal—equal in certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness'."[32]

Lincoln–Douglas debates

Douglas was up for re-election in 1858, and Lincoln hoped to defeat the powerful Illinois Democrat. With the former Democrat Trumbull now serving as a Republican Senator, many in the party felt that a former Whig should be nominated in 1858, and Lincoln's 1856 campaigning and willingness to support Trumbull in 1854 had earned him favor in the party.[33] Some eastern Republicans favored the reelection of Douglas for the Senate in 1858, since he had led the opposition to the Lecompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state.[34] But many Illinois Republicans resented this eastern interference. For the first time, Illinois Republicans held a convention to agree upon a Senate candidate, and Lincoln won the party's Senate nomination with little opposition.[35]

Accepting the nomination, Lincoln delivered his House Divided Speech, drawing on Mark 3:25, "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other."[36] The speech created an evocative image of the danger of disunion caused by the slavery debate, and rallied Republicans across the North.[37] The stage was then set for the campaign for statewide election of the Illinois legislature which would, in turn, select Lincoln or Douglas as its U.S. senator.[38] On being informed of Lincoln's nomination, Douglas stated, "[Lincoln] is the strong man of the party ... and if I beat him, my victory will be hardly won."[39]

The Senate campaign featured the seven Lincoln–Douglas debates of 1858, the most famous political debates in American history.[40] The principals stood in stark contrast both physically and politically. Lincoln warned that "The Slave Power" was threatening the values of republicanism, and accused Douglas of distorting the values of the Founding Fathers that all men are created equal, while Douglas emphasized his Freeport Doctrine, that local settlers were free to choose whether to allow slavery or not, and accused Lincoln of having joined the abolitionists.[41] The debates had an atmosphere of a prize fight and drew crowds in the thousands. Lincoln stated Douglas' popular sovereignty theory was a threat to the nation's morality and that Douglas represented a conspiracy to extend slavery to free states. Douglas said that Lincoln was defying the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court and the Dred Scott decision.[42]

Though the Republican legislative candidates won more popular votes, the Democrats won more seats, and the legislature re-elected Douglas to the Senate. Despite the bitterness of the defeat for Lincoln, his articulation of the issues gave him a national political reputation.[43]

Cooper Union speech

In May 1859, Lincoln purchased the Illinois Staats-Anzeiger, a German-language newspaper which was consistently supportive; most of the state's 130,000 German Americans voted Democratic but there was Republican support that a German-language paper could mobilize.[44] In the aftermath of the 1858 election, newspapers frequently mentioned Lincoln as a potential Republican presidential candidate in 1860, with William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates, and Simon Cameron looming as rivals for the nomination. While Lincoln was popular in the Midwest, he lacked support in the Northeast, and was unsure as to whether he should seek the presidency.[45] In January 1860, Lincoln told a group of political allies that he would accept the 1860 presidential nomination if offered, and in the following months several local papers endorsed Lincoln for president.[46]

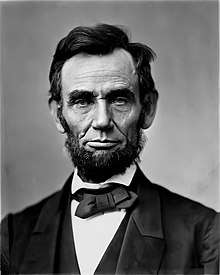

On February 27, 1860, New York party leaders invited Lincoln to give a speech at Cooper Union to a group of powerful Republicans. Lincoln argued that the Founding Fathers had little use for popular sovereignty and had repeatedly sought to restrict slavery. Lincoln insisted the moral foundation of the Republicans required opposition to slavery, and rejected any "groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong".[47] Despite his inelegant appearance—many in the audience thought him awkward and even ugly[48]—Lincoln demonstrated an intellectual leadership that brought him into the front ranks of the party and into contention for the Republican presidential nomination. Journalist Noah Brooks reported, "No man ever before made such an impression on his first appeal to a New York audience."[49][50]

Historian Donald described the speech as a "superb political move for an unannounced candidate, to appear in one rival's (Seward) own state at an event sponsored by the second rival's (Chase) loyalists, while not mentioning either by name during its delivery".[51] In response to an inquiry about his presidential intentions, Lincoln said, "The taste is in my mouth a little."[52]

1860 presidential election

Republican nomination

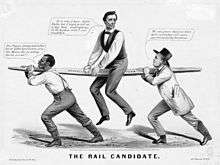

On May 9–10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur.[53] Lincoln's followers organized a campaign team led by David Davis, Norman Judd, Leonard Swett, and Jesse DuBois, and Lincoln received his first endorsement to run for the presidency.[54] Exploiting the embellished legend of his frontier days with his father (clearing the land and splitting fence rails with an ax), Lincoln's supporters adopted the label of "The Rail Candidate".[55] In 1860 Lincoln described himself: "I am in height, six feet, four inches, nearly; lean in flesh, weighing, on an average, one hundred and eighty pounds; dark complexion, with coarse black hair, and gray eyes."[56]

On May 18, at the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Lincoln became the Republican candidate on the third ballot, beating candidates such as Seward and Chase. A former Democrat, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, was nominated for Vice President to balance the ticket. Lincoln's success depended on his campaign team, his reputation as a moderate on the slavery issue, and his strong support for Whiggish programs of internal improvements and the protective tariff.[57]

On the third ballot Pennsylvania put him over the top. Pennsylvania iron interests were reassured by his support for protective tariffs.[58] Lincoln's managers had been adroitly focused on this delegation as well as the others, while following Lincoln's strong dictate to "Make no contracts that bind me".[59]

General election

Most Republicans agreed with Lincoln that the North was the aggrieved party, as the Slave Power tightened its grasp on the national government with the Dred Scott decision and the presidency of James Buchanan. Throughout the 1850s, Lincoln doubted the prospects of civil war, and his supporters rejected claims that his election would incite secession.[60] Meanwhile, Douglas was selected as the candidate of the Northern Democrats. Delegates from 11 slave states walked out of the Democratic convention, disagreeing with Douglas' position on popular sovereignty, and ultimately selected incumbent Vice President John C. Breckinridge as their candidate.[61] A group of former Whigs and Know Nothings formed the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell of Tennessee. Lincoln and Douglas would compete for votes in the North, while Bell and Breckinridge primarily found support in the South.[33]

Lincoln had a highly effective campaign team who carefully projected his image as an ideal candidate. As Michael Martinez says:

Lincoln and his political advisers manipulated his image and background....Sometimes he appeared as a straight-shooting, plain-talking, common-sense-wielding man of the people. His image as the "Rail Splitter" dates from this era. His supporters also portrayed him as "Honest Abe," the country fellow who was simply dressed and not especially polished or formal in his manner but who was as honest and trustworthy as his legs were long. Even Lincoln's tall, gangly frame was used to good advantage during the campaign as many drawings and posters show the candidates sprinting past his vertically challenged rivals. At other times, Lincoln appeared as a sophisticated, thoughtful, articulate, "presidential" candidate.[62]

Prior to the Republican convention, the Lincoln campaign began cultivating a nationwide youth organization, the Wide Awakes, which it used to generate popular support for Lincoln throughout the country to spearhead large voter registration drives, knowing that new voters and young voters tend to embrace new and young parties.[63] As Lincoln's ideas of abolishing slavery grew, so did his supporters. People of the Northern states knew the Southern states would vote against Lincoln because of his ideas of anti-slavery and took action to rally supporters for Lincoln.[64]

As Douglas and the other candidates went through with their campaigns, Lincoln was the only one of them who gave no speeches. Instead, he monitored the campaign closely and relied on the enthusiasm of the Republican Party. The party did the leg work that produced majorities across the North, and produced an abundance of campaign posters, leaflets, and newspaper editorials. There were thousands of Republican speakers who focused first on the party platform, and second on Lincoln's life story, emphasizing his childhood poverty. The goal was to demonstrate the superior power of "free labor", whereby a common farm boy could work his way to the top by his own efforts.[65] The Republican Party's production of campaign literature dwarfed the combined opposition; a Chicago Tribune writer produced a pamphlet that detailed Lincoln's life, and sold 100,000 to 200,000 copies.[66]

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States, beating Douglas, Breckinridge, and Bell. He was the first president from the Republican Party. His victory was entirely due to the strength of his support in the North and West; no ballots were cast for him in 10 of the 15 Southern slave states, and he won only two of 996 counties in all the Southern states.[67]

Lincoln received 1,866,452 votes, Douglas 1,376,957 votes, Breckinridge 849,781 votes, and Bell 588,789 votes. Turnout was 82.2 percent, with Lincoln winning the free Northern states, as well as California and Oregon. Douglas won Missouri, and split New Jersey with Lincoln.[68] Bell won Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky, and Breckinridge won the rest of the South.[69]

Although Lincoln won only a plurality of the popular vote, his victory in the electoral college was decisive: Lincoln had 180 and his opponents added together had only 123. There were fusion tickets in which all of Lincoln's opponents combined to support the same slate of Electors in New York, New Jersey, and Rhode Island, but even if the anti-Lincoln vote had been combined in every state, Lincoln still would have won a majority in the Electoral College.[70]

Transition period

As Lincoln's election became evident, secessionists made clear their intent to leave the Union before he took office the next March.[71] On December 20, 1860, South Carolina took the lead by adopting an ordinance of secession; by February 1, 1861, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas followed.[72][73] Six of these states then adopted a constitution and declared themselves to be a sovereign nation, the Confederate States of America.[72] The upper South and border states (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas) listened to, but initially rejected, the secessionist appeal.[74] President Buchanan and President-elect Lincoln refused to recognize the Confederacy, declaring secession illegal.[75] The Confederacy selected Jefferson Davis as its provisional President on February 9, 1861.[76]

There were attempts at compromise. The Crittenden Compromise would have extended the Missouri Compromise line of 1820, dividing the territories into slave and free, contrary to the Republican Party's free-soil platform.[77] Lincoln rejected the idea, saying, "I will suffer death before I consent ... to any concession or compromise which looks like buying the privilege to take possession of this government to which we have a constitutional right."[78]

Lincoln, however, did tacitly support the proposed Corwin Amendment to the Constitution, which passed Congress before Lincoln came into office and was then awaiting ratification by the states. That proposed amendment would have protected slavery in states where it already existed and would have guaranteed that Congress would not interfere with slavery without Southern consent.[79][80] A few weeks before the war, Lincoln sent a letter to every governor informing them Congress had passed a joint resolution to amend the Constitution.[81] Lincoln was open to the possibility of a constitutional convention to make further amendments to the Constitution.[82]

En route to his inauguration by train, Lincoln addressed crowds and legislatures across the North.[83] The president-elect then evaded possible assassins in Baltimore, who were uncovered by Lincoln's head of security, Allan Pinkerton. On February 23, 1861, he arrived in disguise in Washington, D.C., which was placed under substantial military guard.[84] Lincoln directed his inaugural address to the South, proclaiming once again that he had no intention, or inclination, to abolish slavery in the Southern states:

Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by the accession of a Republican Administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that "I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so."

The President ended his address with an appeal to the people of the South: "We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies ... The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."[86] The failure of the Peace Conference of 1861 signaled that legislative compromise was impossible. By March 1861, no leaders of the insurrection had proposed rejoining the Union on any terms. Meanwhile, Lincoln and the Republican leadership agreed that the dismantling of the Union could not be tolerated.[87] Lincoln said as the war was ending:[88]

Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the Nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came.

See also

References

- Donald (1996), p. 222.

- Boritt (1994), pp. 137–153.

- Oates, p. 79.

- Harris, p. 54; Foner (2010), p. 57.

- Donald (1996), pp. 124–126.

- Donald (1996), p. 140.

- Arnold, Isaac Newton (1885). The Life of Abraham Lincoln. 2. Chicago, IL: Janses, McClurg, & Company. p. 81. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017.

- Harris, pp. 55–57.

- Donald (1996), p. 96.

- Donald (1996), pp. 105–106, 158.

- White, pp. 175–176.

- White, pp. 182–185.

- White, pp. 188–190.

- White, pp. 196–197.

- Thomas (2008), pp. 148–152.

- White, p. 199.

- Basler (1953), p. 255.

- White, pp. 203–205.

- White, pp. 215–216.

- McGovern, pp. 38–39.

- White, pp. 203–204.

- White, pp. 191–194.

- White, pp. 204–205.

- Oates, p. 119.

- White, pp. 205–208.

- White, pp. 216–221.

- White, pp. 224–228.

- White, pp. 229–230.

- Foner (2010), pp. 84–88.

- White, pp. 236–238.

- Zarefsky, pp. 69–110.

- Jaffa, pp. 299–300.

- White, pp. 247–248.

- Oates, pp. 138–139.

- White, pp. 247–250.

- White, p. 251.

- Harris, p. 98.

- Donald (1996), p. 209.

- White, pp. 257–258.

- McPherson (1993), p. 182.

- Donald (1996), pp. 214–224.

- Donald (1996), p. 223.

- Carwardine (2003), pp. 89–90.

- Donald (1996), pp. 242, 412.

- White, pp. 291–293.

- White, pp. 307–308.

- Jaffa, p. 473.

- Holzer, pp. 108–111.

- Carwardine (2003), p. 97.

- Holzer, p. 157.

- Donald (1996), p. 240.

- Donald (1996), p. 241.

- Donald (1996), p. 244.

- Oates, pp. 175–176.

- Donald (1996), p. 245.

- Lincoln, Abraham (December 20, 1859). "Herewith is a little sketch, as you requested". Letter to Jesse W. Fell. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- Luthin, pp. 609–629.

- Hofstadter, pp. 50–55.

- Donald (1996), pp. 247–250.

- Boritt (1994), pp. 10, 13, 18.

- Donald (1996), p. 253.

- J. Michael Martinez (2011). Coming for to Carry Me Home: Race in America from Abolitionism to Jim Crow. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4422-1500-9. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- Chadwick, Bruce (2009). Lincoln for President: An Unlikely Candidate, An Audacious Strategy, and the Victory No One Saw Coming. Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks. pp. 147–149. ISBN 978-1-4022-4756-9. Archived from the original on April 2, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- Murrin, John. Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People. Belmont: Clark Baxter, 2006.

- Donald (1996), pp. 254–256.

- Donald (1996), p. 254.

- Mansch, p. 61.

- Harris, p. 243.

- White, p. 350.

- Nevins, Ordeal of the Union vol 4. p. 312.

- Edgar, p. 350.

- Donald (1996), p. 267.

- Potter, p. 498.

- White, p. 362.

- Potter, pp. 520, 569–570.

- White, p. 369.

- White, pp. 360–361.

- Donald (1996), p. 268.

- Vorenberg, p. 22.

- Vile (2003), Encyclopedia of Constitutional Amendments: Proposed Amendments, and Amending Issues 1789–2002 pp. 280–281

- Lupton (2006), Abraham Lincoln and the Corwin Amendment Archived August 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 13, 2013

- Vile (2003), Encyclopedia of Constitutional Amendments: Proposed Amendments, and Amending Issues 1789–2002 p. 281

- Donald (1996), pp. 273–277.

- Donald (1996), pp. 277–279.

- Sandburg (2002), p. 212.

- Donald (1996), pp. 283–284.

- Donald (1996), pp. 268, 279.

- March 4, 1865, Lincoln's second inaugural address.

Bibliography

- Adams, Charles F. (April 1912). "The Trent Affair". The American Historical Review. 17 (3): 540–562. doi:10.2307/1834388. JSTOR 1834388.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1962). Halleck: Lincoln's Chief of Staff. Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 1178496.

- Baker, Jean H. (1989). Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-30586-9.

- Bartelt, William E. (2008). There I Grew Up: Remembering Abraham Lincoln's Indiana Youth. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-87195-263-9.

- Basler, Roy Prentice, ed. (1946). Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings. World Publishing. OCLC 518824.

- Basler, Roy P., ed. (1953). The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. 5. Rutgers University Press.

- Belz, Herman (1998). Abraham Lincoln, Constitutionalism, and Equal Rights in the Civil War Era. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-1769-4.

- Belz, Herman (2006). "Lincoln, Abraham". In Frohnen, Bruce; Beer, Jeremy; Nelson, Jeffrey O (eds.). American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia. ISI Books. ISBN 978-1-932236-43-9.

- Bennett, Lerone, Jr. (February 1968). "Was Abe Lincoln a White Supremacist?". Ebony. Vol. 23 no. 4. ISSN 0012-9011.

- Blue, Frederick J. (1987). Salmon P. Chase: a life in politics. The Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-340-0.

- Boritt, Gabor S. (1997). Why the Civil War Came. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511376-1.

- Boritt, Gabor (1994) [1978]. Lincoln and the Economics of the American Dream. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06445-6.

- Boritt, Gabor S.; Pinsker, Matthew (2002). "Abraham Lincoln". In Graff, Henry (ed.). The Presidents: A Reference History (7th ed.). pp. 209–223. ISBN 978-0-684-80551-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bulla, David W.; Gregory A. Borchard (2010). Journalism in the Civil War Era. Peter Lang Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-4331-0722-1.

- Burlingame, Michael (2008). Abraham Lincoln: A Life. I. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8993-6.

- Carwardine, Richard J. (Winter 1997). "Lincoln, Evangelical Religion, and American Political Culture in the Era of the Civil War". Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. 18 (1): 27–55. hdl:2027/spo.2629860.0018.104.

- Carwardine, Richard (2003). Lincoln. Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 978-0-582-03279-8.

- Cashin, Joan E. (2002). The War Was You and Me: Civilians in The American Civil War. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09173-0.

- Chesebrough, David B. (1994). No Sorrow Like Our Sorrow. Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-491-9.

- Cox, Hank H. (2005). Lincoln and the Sioux Uprising of 1862. Cumberland House Publisher. ISBN 978-1-58182-457-5.

- Cummings, William W.; James B. Hatcher (1982). Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps. Scott Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-89487-042-2.

- Dennis, Matthew (2002). Red, White, and Blue Letter Days: an American Calendar. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7268-8.

- Diggins, John P. (1986). The Lost Soul of American Politics: Virtue, Self-Interest, and the Foundations of Liberalism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-14877-9.

- Dirck, Brian R. (2007). Lincoln Emancipated: The President and the Politics of Race. Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-87580-359-3.

- Dirck, Brian (2008). Lincoln the Lawyer. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07614-5.

- Donald, David Herbert (1948). Lincoln's Herndon. A. A. Knopf. OCLC 186314258.

- Donald, David Herbert (1996) [1995]. Lincoln. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-82535-9. online

- Donald, David Herbert (2001). Lincoln Reconsidered. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-375-72532-6. online

- Douglass, Frederick (2008). The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Cosimo Classics. ISBN 978-1-60520-399-7.

- Edgar, Walter B. (1998). South Carolina: A History. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-255-4.

- Fish, Carl Russell (October 1902). "Lincoln and the Patronage". American Historical Review. 8 (1): 53–69. doi:10.2307/1832574. JSTOR 1832574.

- Foner, Eric (1995) [1970]. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509497-8.

- Foner, Eric (2010). The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06618-0.

- Gerleman, David J. (Winter 2017). "Representative Lincoln at Work: Reconstructing a Legislative Career from Original Archival Documents". The Capitol Dome. 54 (2): 33–46.

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2005). Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-82490-1.

- Goodrich, Thomas (2005). The Darkest Dawn: Lincoln, Booth, and the Great American Tragedy. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34567-7.

- Graebner, Norman (1959). "Abraham Lincoln: Conservative Statesman". The Enduring Lincoln: Lincoln Sesquicentennial Lectures at the University of Illinois. University of Illinois Press. OCLC 428674.

- Grimsley, Mark (2001). The Collapse of the Confederacy. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2170-3.

- Guelzo, Allen C. (1999). Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President. W.B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3872-8. free to borrow

- Guelzo, Allen C. (2004). Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-2182-5.

- Guelzo, Allen C. (2009). Lincoln: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-536780-4.

- Handy, James S. (1917). Book Review: Abraham Lincoln, the Lawyer-Statesman. Northwestern University Law Publication Association.

- Harrison, J. Houston (1935). Settlers by the Long Grey Trail. J.K. Reubush. OCLC 3512772.

- Harrison, Lowell Hayes (2000). Lincoln of Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2156-7.

- Harris, William C. (2007). Lincoln's Rise to the Presidency. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1520-9.

- Havers, Grant N. (2009). Lincoln and the Politics of Christian Love. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1857-5.

- Heidler, David S.; Heidler, Jeanne T., eds. (2000). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-04758-5.

- Heidler, David Stephen (2006). The Mexican War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32792-6.

- Hofstadter, Richard (October 1938). "The Tariff Issue on the Eve of the Civil War". American Historical Review. 44 (1): 50–55. doi:10.2307/1840850. JSTOR 1840850.

- Holzer, Harold (2004). Lincoln at Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-9964-0.

- Jaffa, Harry V. (2000). A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9952-0.

- Kelley, Robin D. G.; Lewis, Earl (2005). To Make Our World Anew: Volume I: A History of African Americans to 1880. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-804006-4.

- Lamb, Brian; Swain, Susan, eds. (2008). Abraham Lincoln: Great American Historians on Our Sixteenth President. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-676-1.

- Lupton, John A. (September–October 2006). "Abraham Lincoln and the Corwin Amendment". Illinois Heritage. 9 (5): 34.

- Luthin, Reinhard H. (1944). The First Lincoln Campaign. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-8446-1292-8.

- Luthin, Reinhard H. (July 1994). "Abraham Lincoln and the Tariff". American Historical Review. 49 (4): 609–629. doi:10.2307/1850218. JSTOR 1850218.

- McClintock, Russell (2008). Lincoln and the Decision for War: The Northern Response to Secession. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3188-5. Online preview.

- Madison, James H. (2014). Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press and Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-253-01308-8.

- Mansch, Larry D. (2005). Abraham Lincoln, President-Elect: The Four Critical Months from Election to Inauguration. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2026-1.

- McGovern, George S. (2008). Abraham Lincoln. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-8345-3.

- McKirdy, Charles Robert (2011). Lincoln Apostate: The Matson Slave Case. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-987-9.

- McPherson, James M. (1992). Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507606-6.

- McPherson, James M. (1993). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516895-2.

- McPherson, James M. (2009). Abraham Lincoln. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537452-0.

- Miller, William Lee (2002). Lincoln's Virtues: An Ethical Biography (Vintage Books ed.). New York: Random House/Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-375-40158-9.

- Neely, Mark E. (1992). The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–31.; Pulitzer Proze

- Neely Jr., Mark E. (December 2004). "Was the Civil War a Total War?". Civil War History. 50 (4): 434–458. doi:10.1353/cwh.2004.0073.

- Nevins, Allan (1947–71). Ordeal of the Union; 8 vol. Scribner's. ISBN 978-0-684-10416-4.

- Nevins, Allan (1950). The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1857–1861 2 vol. Scribner's. ISBN 978-0-684-10416-4., also published as vol 3–4 of Ordeal of the Union

- Nevins, Allan (1960–1971). The War for the Union; 4 vol 1861–1865. Scribner's. ISBN 978-1-56852-297-5.; also published as vol 5–8 of Ordeal of the Union

- Nichols, David A. (2010). Richard W. Etulain (ed.). Lincoln Looks West: From the Mississippi to the Pacific. Southern Illinois University. ISBN 978-0-8093-2961-8.

- Noll, Mark (2000). America's God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515111-4.

- Oates, Stephen B. (1974). "Abraham Lincoln 1861–1865". In C. Vann Woodward (ed.). Responses of the Presidents to Charges of Misconduct. New York City: Dell Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 111–123. ISBN 978-0-440-05923-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oates, Stephen B. (1993). With Malice Toward None: a Life of Abraham Lincoln. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-092471-3.

- Paludan, Phillip Shaw (1994). The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0671-9.

- Parrillo, Nicholas (September 2000). "Lincoln's Calvinist Transformation: Emancipation and War". Civil War History. 46 (3): 227–253. doi:10.1353/cwh.2000.0073.

- Peterson, Merrill D. (1995). Lincoln in American Memory. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509645-3.

- Potter, David M.; Don Edward Fehrenbacher (1976). The impending crisis, 1848–1861. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-131929-7.

- Prokopowicz, Gerald J. (2008). Did Lincoln Own Slaves?. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-307-27929-3.

- Randall, James G. (1947). Lincoln, the Liberal Statesman. Dodd, Mead. OCLC 748479.

- Randall, J.G.; Current, Richard Nelson (1955). Last Full Measure. Lincoln the President. IV. Dodd, Mead. OCLC 5852442.

- Reinhart, Mark S. (2008). Abraham Lincoln on Screen. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3536-4.

- Sandburg, Carl (1926). Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years. Harcourt, Brace & Company. OCLC 6579822.

- Sandburg, Carl (2002). Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15-602752-6.

- Schwartz, Barry (2000). Abraham Lincoln and the Forge of National Memory. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-74197-0.

- Schwartz, Barry (2009). Abraham Lincoln in the Post-Heroic Era: History and Memory in Late Twentieth-Century America. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-74188-8.

- Scott, Kenneth (September 1948). "Press Opposition to Lincoln in New Hampshire". The New England Quarterly. 21 (3): 326–341. doi:10.2307/361094. JSTOR 361094.

- Scott (2005). Scott 2006 Classic Specialized Catalogue. Scott Pub. Co. ISBN 0-89487-358-X.

- Sherman, William T. (1990). Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-174-63172-6.

- Simon, Paul (1990). Lincoln's Preparation for Greatness: The Illinois Legislative Years. University of Illinois. ISBN 978-0-252-00203-8.

- Smith, Robert C. (2010). Conservatism and Racism, and Why in America They Are the Same. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-3233-5.

- Steers, Edward (2010). The Lincoln Assassination Encyclopedia. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-178775-1.

- Striner, Richard (2006). Father Abraham: Lincoln's Relentless Struggle to End Slavery. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518306-1.

- Tagg, Larry (2009). The Unpopular Mr. Lincoln:The Story of America's Most Reviled President. Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-61-6.

- Taranto, James; Leonard Leo (2004). Presidential Leadership: Rating the Best and the Worst in the White House. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5433-5.

- Tegeder, Vincent G. (June 1948). "Lincoln and the Territorial Patronage: The Ascendancy of the Radicals in the West". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 35 (1): 77–90. doi:10.2307/1895140. JSTOR 1895140.

- Thomas, Emory M. (2007). Gordon, Lesley J.; Inscoe, John C. (eds.). Inside the Confederate Nation: Essays in Honor of Emory M. Thomas. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3231-9.

- Thomas, Benjamin P. (2008). Abraham Lincoln: A Biography. Southern Illinois University. ISBN 978-0-8093-2887-1. online

- Trostel, Scott D. (2002). The Lincoln Funeral Train: The Final Journey and National Funeral for Abraham Lincoln. Cam-Tech Publishing. ISBN 978-0-925436-21-4.

- Vorenberg, Michael (2001). Final Freedom: the Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65267-4.

- Warren, Louis A. (1991). Lincoln's Youth: Indiana Years, Seven to Twenty-One, 1816–1830. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87195-063-5.

- White Jr., Ronald C. (2009). A. Lincoln: A Biography. Random House, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4000-6499-1.

- Wills, Garry (1993). Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86742-3.

- Wilson, Douglas L. (1999). Honor's Voice: The Transformation of Abraham Lincoln. Knopf Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-375-70396-6.

- Winkle, Kenneth J. (2001). The Young Eagle: The Rise of Abraham Lincoln. Taylor Trade Publications. ISBN 978-0-87833-255-7.

- Zarefsky, David S. (1993). Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery: In the Crucible of Public Debate. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-97876-5.