D. W. Griffith

David Wark Griffith (January 22, 1875 – July 23, 1948) was an American film director. Widely considered as the most important filmmaker of his generation, he pioneered financing of the feature-length movie.

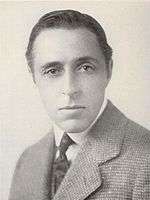

D. W. Griffith | |

|---|---|

Griffith in 1922 | |

| Born | David Wark Griffith January 22, 1875 Oldham County, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | July 23, 1948 (aged 73) Hollywood, California, U.S. |

| Burial place | Mount Tabor Methodist Church Graveyard, Centerfield, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1908–1931 |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Signature | |

His film The Birth of a Nation (1915) made investors a profit, but also attracted much controversy, as it depicted African Americans in a negative light and glorified the Ku Klux Klan. Intolerance (1916) was made as an answer to his critics, but not as an apology for the negative images of African Americans in film. Several of Griffith's later films were also successful, including Broken Blossoms (1919), Way Down East (1920) and Orphans of the Storm (1921), but the high costs he incurred for production and promotion often led to commercial failure. He had made roughly 500 films by the time of his final feature, The Struggle (1931).

Together with Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks he founded United Artists, enabling them to control their own interests, rather than depending on commercial studios. Griffith was also a founding member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Early life

Griffith was born on a farm in Oldham County, Kentucky, the son of Jacob Wark "Roaring Jake" Griffith,[1] a Confederate Army colonel in the American Civil War who was elected as a Kentucky state legislator, and Mary Perkins (née Oglesby). Griffith was raised as a Methodist,[2] and he attended a one-room schoolhouse, where he was taught by his older sister Mattie. His father died when he was 10, and the family struggled with poverty.

When Griffith was 14, his mother abandoned the farm and moved the family to Louisville, Kentucky; there she opened a boarding house, which failed shortly afterward. Griffith then left high school to help support the family, taking a job in a dry goods store and later in a bookstore. He began his creative career as an actor in touring companies. Meanwhile, he was learning how to become a playwright, but had little success—only one of his plays was accepted for a performance.[3] He traveled to New York City in 1907 in an attempt to sell a script to Edison Studios producer Edwin Porter;[3] however, Porter rejected the script, but gave him an acting part in Rescued from an Eagle's Nest instead.[3] He then decided to become an actor and appeared in many films as an extra.[4]

Film career

In 1908, Griffith accepted a role as a stage extra in Professional Jealousy for the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, where he met cameraman Billy Bitzer, and his career in the film industry changed forever.[5] In 1908, Biograph's main director Wallace McCutcheon, Sr. grew ill, and his son Wallace McCutcheon, Jr. took his place.[6] McCutcheon, Jr. did not bring the studio success;[5] Biograph co-founder Harry Marvin gave Griffith the position,[5] and he made the short The Adventures of Dollie. He directed a total of 48 shorts for the company that year.

Among the films he directed in 1909 was The Cricket on the Hearth, an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ novel. On the influence of Dickens on his own film narrative, Griffith employed the technique of cross-cutting—where two stories run alongside each other, as seen in Dickens’ novels such as Oliver Twist.[7] When criticized by a cameraman for doing this in a later film, Griffith was said to have replied, "Well, doesn't Dickens write that way?".[7]

His short In Old California (1910) was the first film shot in Hollywood, California. Four years later, he produced and directed his first feature film Judith of Bethulia (1914), one of the earlier to be produced in the U.S. Biograph believed that longer features were not viable at this point. According to Lillian Gish, the company thought that "a movie that long would hurt [the audience's] eyes".[8]

Griffith left Biograph because of company resistance to his goals and his cost overruns on the film. He took his company of actors with him and joined the Mutual Film Corporation. There he co-produced The Life of General Villa, a biographical-action movie starring Pancho Villa as himself, shot on location in Mexico during a civil war. He formed a studio with Majestic Studios manager Harry Aitken,[9] which became known as Reliance-Majestic Studios and later was renamed Fine Arts Studios.[10] His new production company became an autonomous production unit partner in the Triangle Film Corporation along with Thomas H. Ince and Keystone Studios' Mack Sennett. The Triangle Film Corporation was headed by Aitken, who was released from the Mutual Film Corporation,[9] and his brother Roy.

Griffith directed and produced The Clansman through Reliance-Majestic Studios in 1915, which became known as The Birth of a Nation and is considered one of the early feature length American films.[11] The film was a success, but it aroused much controversy due to its depiction of slavery, the Ku Klux Klan and race relations in the American Civil War and the reconstruction era of the United States. It was based on Thomas Dixon, Jr.'s 1905 novel The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan; it depicts Southern slavery as benign, the enfranchisement of freedmen as a corrupt plot by the Republican Party, and the Ku Klux Klan as a band of heroes restoring the rightful order. This view of the era was popular at the time and was endorsed for decades by historians of the Dunning School, although it met with strong criticism from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other groups.[12][13]

The NAACP attempted to stop showings of the film. This was successful in some cities, but nonetheless it was shown widely and became the most successful box-office attraction of its time. It is considered among the first "blockbuster" motion pictures, and broke all box office records that had been established until then. "They lost track of the money it made", Lillian Gish remarked in a Kevin Brownlow interview.

Audiences in some major northern cities rioted over the film's racial content, which was filled with action and violence.[14] Griffith's indignation at efforts to censor or ban the film motivated him to produce Intolerance the following year, in which he portrayed the effects of intolerance in four different historical periods: the Fall of Babylon; the Crucifixion of Jesus; the events surrounding the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (during religious persecution of French Huguenots); and a modern story. Intolerance was not a financial success; it did not bring in enough profits to cover the lavish road show that accompanied it.[15] Griffith put a huge budget into the film's production that could not be recovered in its box office.[16] He mostly financed Intolerance himself, contributing to his financial ruin for the rest of his life.[17]

Griffith's production partnership was dissolved in 1917, and he went to Artcraft, part of Paramount Pictures, and then to First National Pictures (1919–1920). At the same time, he founded United Artists together with Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks; the studio was premised on allowing actors to control their own interests rather than being dependent upon commercial studios.[18][19]

He continued to make films, but never achieved box-office grosses again as high as either The Birth of a Nation or Intolerance.[20]

Later film career

Though United Artists survived as a company, Griffith's association with it was short-lived. While some of his later films did well at the box office, commercial success often eluded him. Griffith features from this period include Broken Blossoms (1919), Way Down East (1920), Orphans of the Storm (1921), Dream Street (1921), One Exciting Night (1922) and America (1924). Of these, the first three were successes at the box office.[21] Griffith was forced to leave United Artists after Isn't Life Wonderful (1924) failed at the box office.

He made a part-talkie, Lady of the Pavements (1929), and only two full-sound films: Abraham Lincoln (1930) and The Struggle (1931). Neither was successful, and after The Struggle he never made another film.

In 1936, director Woody Van Dyke, who had worked as Griffith's apprentice on Intolerance, asked Griffith to help him shoot the famous earthquake sequence for San Francisco, but did not give him any film credit. Starring Clark Gable, Jeanette MacDonald and Spencer Tracy, it was the top-grossing film of the year.[22]

In 1939, the producer Hal Roach hired Griffith to produce Of Mice and Men (1939) and One Million B.C. (1940). He wrote to Griffith: "I need help from the production side to select the proper writers, cast, et cetera, and to help me generally in the supervision of these pictures."[23]

Although Griffith eventually disagreed with Roach over the production and parted, Roach later insisted that some of the scenes in the completed film were directed by Griffith. This would make the film the final production in which Griffith was actively involved. However, cast members' accounts recall Griffith directing only the screen tests and costume tests. When Roach advertised the film in late 1939 with Griffith listed as producer, the latter asked that his name be removed.[24]

Although mostly forgotten by movie-goers of the time Griffith was held in awe by many in the film industry. In the mid-1930s he was given a special Oscar by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. In 1946 he made an impromptu visit to the film location of David O. Selznick's epic western Duel in the Sun, where some of his veteran actors, Lillian Gish, Lionel Barrymore and Harry Carey, were cast members. Gish and Barrymore found their old mentor's presence distracting and became self-conscious so, when the two were filming their scenes, Griffith hid behind the scenery.[25]

Death

On the morning of July 23, 1948, Griffith was discovered unconscious in the lobby at the Knickerbocker Hotel in Los Angeles, where he had been living alone. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage at 3:42 PM on the way to a Hollywood hospital.[18] A public memorial service was held in his honor at the Hollywood Masonic Temple, but few stars came to pay their last respects. He is buried at Mount Tabor Methodist Church Graveyard in Centerfield, Kentucky.[26] In 1950, The Directors Guild of America provided a stone and bronze monument for his grave site.[27]

Legacy

Performer and director Charlie Chaplin called Griffith "The Teacher of Us All". Filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock,[28] Lev Kuleshov,[29] Jean Renoir,[30] Cecil B. DeMille,[31] King Vidor,[32] Victor Fleming,[33] Raoul Walsh,[34] Carl Theodor Dreyer,[35] Sergei Eisenstein,[36] and Stanley Kubrick have praised Griffith.[37]

Griffith seems to have been the first to understand how certain film techniques could be used to create an expressive language; it gained popular recognition with the release of his The Birth of a Nation (1915). His early shorts —such as Biograph's The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912), the first "gangster film"— show that Griffith's attention to camera placement and lighting heightened mood and tension. In making Intolerance the director opened up new possibilities for the medium, creating a form that seems to owe more to music than to traditional narrative.[38][39]

A large part of Griffith's legacy is that he perpetuated racist stereotypes and opened the gateway to prejudice in mainstream Hollywood film. Refusing to apologize for the messages in his movies, he helped enable a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1910s and 1920s, enabling the onset of violence against black people and minorities in the United States. The Lost Cause post Civil War narrative fabricated by Confederate politicians and high ranking military has considered to be factual history after audiences saw it on the big silver screen.

- In the 1951 Philco Television Playhouse episode "The Birth of the Movies" events from Griffith's film career were depicted. The director was played by John Newland.

- In 1953 the Directors Guild of America (DGA) instituted the D. W. Griffith Award, its highest honor. However, on December 15, 1999 then DGA President Jack Shea and the DGA National Board announced that the award would be renamed as the "DGA Lifetime Achievement Award". They stated that, although Griffith was extremely talented, they felt his film The Birth of a Nation had "helped foster intolerable racial stereotypes", and that it was thus better not to have the top award in his name.

- In 1975 Griffith was honored on a ten-cent postage stamp by the United States.

- The 1976 American comedy film Nickelodeon in part pays homage to silent film makers and includes footage from The Birth of a Nation.

- D. W. Griffith Middle School in Los Angeles is named after Griffith.[40] Because of the association of Griffith and the racist nature of The Birth of a Nation, attempts have been made to rename the 99% minority-enrolled school.[41]

- In 2008 the Hollywood Heritage Museum hosted a screening of Griffith's earliest films to commemorate the centennial of his start in film.[42]

- On January 22, 2009 the Oldham History Center in La Grange, Kentucky opened a 15-seat theatre in Griffith's honor. The theatre features a library of available Griffith films.

Film preservation

Griffith has six films preserved on the United States National Film Registry deemed as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". These are Lady Helen's Escapade (1909), A Corner in Wheat (1909), The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912), The Birth of a Nation (1915), Intolerance (1916) and Broken Blossoms (1919).

See also

References

- "D.W. Griffith (1875–1948)". Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- Blizek, William L. (2009). The Continuum Companion to Religion and Film. A&C Black. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-8264-9991-2.

- "D.W. Griffith". Spartacus-Educational.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- "American Experience | Mary Pickford". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- "D.W. Griffith Biography". Starpulse.com. July 23, 1948. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- "Who's Who of Victorian Cinema". Victorian-cinema.net. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- "Dickens on screen: the highs and the lows". The Guardian. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Kirsner, Scott (2008). Inventing the movies : Hollywood's epic battle between innovation and the status quo, from Thomas Edison to Steve Jobs (1st ed.). [s.l.]: CinemaTech Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4382-0999-9.

- "D.W. Griffith: Hollywood Independent". Cobbles.com. June 26, 1917. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- "Fine Arts Studio". Employees.oxy.edu. June 9, 1917. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- Devore, Dan. "Birth of a Nation, The (1915)", Movie Justice Movie Review, January 23, 2003. Internet Archive Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- "'The Birth of a Nation': When Hollywood Glorified the KKK |". HistoryNet. June 12, 2006. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- Brooks, Xan (July 29, 2013). "The Birth of a Nation: a gripping masterpiece … and a stain on history". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- "The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow". PBS. March 21, 1915. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- ""Griffith's 20 Year Record"". Cinemaweb.com. September 5, 1928. Archived from the original on July 12, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- "Intolerance Movie Review". Contactmusic.com. May 29, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- Georges Sadoul (1972 [1965]). Dictionary of Films, P. Morris, ed. & trans., p. 158. UCP.

- "David W. Griffith, Film Pioneer, Dies; Producer of 'Birth of Nation,' 'Intolerance' and 'America' Made Nearly 500 Pictures Set, Screen Standards Co-Founder of United Artists Gave Mary Pickford and Fairbanks Their Starts". The New York Times. July 24, 1948.

- Woo, Elaine (September 29, 2011). "Mo Rothman dies at 92; found new audience for Chaplin". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- "American Masters. D.W. Griffith". PBS. December 29, 1998. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- "Last Dissolve". Time Magazine. August 2, 1948. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- "Biggest Box Office Hits of 1936". Ultimate movie rankings. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- Richard Lewis Ward, A History of the Hal Roach Studios, p. 109-110. Southern Illinois University, 2005. ISBN 0-8093-2637-X. In his Biograph days Griffith had directed two films with prehistoric settings: Man's Genesis (1912) and Brute Force (1914).

- Ward, p. 110.

- Green, Paul (2011). Jennifer Jones: The Life and Films. McFarland. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7864-8583-3.

- Schickel, Richard (1996). D.W. Griffith: An American Life. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 31. ISBN 0-87910-080-X.

- Schickel, Richard (1996). D.W. Griffith: An American Life. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 605. ISBN 0-87910-080-X.

- Leitch, Thomas; Poague, Leland (2011). A Companion to Alfred Hitchcock. John Wiley & Sons. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-4443-9731-4.

- "Landmarks of Early Soviet Film". Archived from the original on April 23, 2012. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- "Jean Renoir Biography". biography.yourdictionary.com. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- "Movie Review: Restored 'Intolerance' Launches Festival of Preservation". latimes.com. July 6, 1990. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- "Overview for King Vidor". tcm.com. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- "Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master". Archived from the original on September 14, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- Moss, Marilyn (2011). Raoul Walsh: The True Adventures of Hollywood's Legendary Director. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 181 and 242. ISBN 978-0-8131-3394-2.

- "Matinee Classics – Carl Dreyer Biography & Filmography". matineeclassics.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- "Sergei Eisenstein – Biography". leninimports.com. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- "D.W. Griffith". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- "D.W. Griffith". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- "History of the Close Up in Film". Archived from the original on October 9, 2017.

- "Griffith Middle School: Home Page". Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- "Petition calls for Griffith Middle School name change over racism – LA School Report". Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- "Hollywood Heritage". Hollywood Heritage. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

Further reading

- Seymour Stern, An Index to the Creative Work of D. W. Griffith (London: The British Film Institute, 1944–47)

- Iris Barry and Eileen Bowser, D. W. Griffith: American Film Master (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1965)

- Kevin Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968)

- David Robinson, Hollywood in the Twenties (New York: A. S. Barnes & Co, Inc., 1968)

- Lillian Gish, The Movies, Mr. Griffith and Me (Englewood, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1969)

- Robert M. Henderson, D. W. Griffith: His Life and Work (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972)

- Karl Brown, Adventures with D. W. Griffith (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1973)

- Edward Wagenknecht and Anthony Slide, The Films of D. W. Griffith (New York: Crown, 1975)

- William K. Everson, American Silent Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978)

- Richard Schickel, D. W. Griffith: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984)

- William M. Drew, D. W. Griffith's "Intolerance:" Its Genesis and Its Vision (Jefferson, New Jersey: McFarland & Company, 1986)

- Tom Gunning, D.W. Griffith and the Origin of the American Narrative: The Early Years at Biograph (Urbana: Illinois University Press, 1994)

- Drew, William M. "D.W. Griffith (1875–1948)". Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- Smith, Matthew (April 2008). "American Valkyries: Richard Wagner, D. W. Griffith, and the Birth of Classical Cinema". Modernism/modernity. 15 (2): 221–42. doi:10.1353/mod.2008.0040.

External links

- Bibliography of books and articles about Griffith via UC Berkeley Media Resources Center

- "The Box in the Screen" Griffith and television

- Photo of Griffith as a young man in the 1890s or early 1900s

- D.W. Griffith in theVanity Fair Hall of Fame (1918)

- A magazine article by the famous director printed in Illustrated World (1921)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to David Wark Griffith. |

D. W. Griffith on IMDb

Works by or about D. W. Griffith at Internet Archive

Works by D. W. Griffith at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks) ![]()