COVID-19 pandemic in the United States

The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The first confirmed local transmission was recorded in January 2020,[8] while the first known deaths were reported in February.[9] By the end of March, cases had occurred in all fifty U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and all inhabited U.S. territories except American Samoa.[10][11]

| COVID-19 pandemic in the United States | |

|---|---|

COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people by state, as of August 15 | |

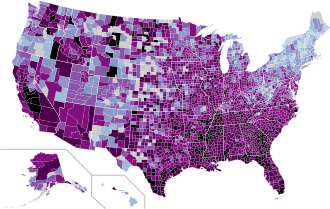

Map of the outbreak in the United States by confirmed new infections per 100,000 people (14 days preceding August 15)

500+ confirmed new cases

200–500 confirmed new cases

100–200 confirmed new cases

50–100 confirmed new cases

20–50 confirmed new cases

10–20 confirmed new cases

0–10 confirmed new cases

No confirmed new cases or no data | |

Map of the outbreak in the United States by total confirmed infections per 100,000 people (as of August 15)

3,000+ confirmed infected

1,000–3,000 confirmed infected

300–1,000 confirmed infected

100–300 confirmed infected

30–100 confirmed infected

0–30 confirmed infected

No confirmed infected or no data | |

| Disease | COVID-19 |

| Virus strain | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Location | United States |

| First outbreak | Wuhan, Hubei, China[1] |

| Index case | Chicago, Illinois (earliest known arrival)[2] Everett, Washington (first case report)[3] |

| Arrival date | January 13, 2020[4] (7 months and 3 days ago) |

| Confirmed cases | |

| Recovered | 1,818,527 (JHU)[6] |

Deaths | |

| Government website | |

| coronavirus | |

Within a week after China announced that it found a cluster of infections from the virus in Wuhan, the CDC offered to send them a team of experts to help contain the spread, but they refused the offer.[12] It was officially declared a public health emergency on January 31, with restrictions then placed on flights arriving from China.[13][14] The initial U.S. response to the pandemic was otherwise slow, in terms of preparing the healthcare system, stopping other travel, or testing for the virus.[15][16][17][lower-alpha 1] Meanwhile, President Donald Trump downplayed the threat posed by the virus and claimed the outbreak was under control.[19]

On March 13, President Trump declared a national emergency.[20] In early March, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began allowing public health agencies and private companies to develop and administer tests, and loosened restrictions so anyone with a doctor's order could be tested.[21]

The Trump administration largely waited until mid-March to start purchasing large quantities of medical equipment.[22] In late March, the administration started to use the Defense Production Act to direct industries to produce medical equipment.[23] Federal health inspectors who surveyed hospitals in late March found shortages of test supplies, personal protective equipment (PPE), and other resources due to extended patient stays while awaiting test results.[24] By April 11, the federal government approved disaster declarations for all states and inhabited territories except American Samoa.[25] By early May, testing had increased, but experts said this level of testing was still not enough to contain the outbreak.[26]

State and local responses to the outbreak have included prohibitions and cancellation of large-scale gatherings (including festivals and sporting events), stay-at-home orders, and the closure of schools.[27] Disproportionate numbers of cases have been observed among Black and Latino populations,[28][29][30] and there were reported incidents of xenophobia and racism against Asian Americans.[31] Clusters of infections and deaths have occurred in urban areas, nursing homes, long-term care facilities, group homes for the intellectually disabled,[32] detention centers (including prisons), meatpacking plants, churches, and navy ships.[33]

A second rise in infections began in June 2020, following relaxed restrictions in several states.[34] In August, the U.S. topped five million confirmed cases while also doing the most per capita testing of any other country.[35][36] Its death rate had reached 499 per million people, the tenth-highest[lower-alpha 2] rate globally.[37][38]

Timeline

December 2019 to January 2020

On December 31, 2019, China reported a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan.[3] On January 6, Health and Human Services offered to send China a team of CDC health experts to help contain the outbreak, but they ignored the offer.[12] According to Dr. Robert Redfield, the director of the CDC, the CDC was ready to send in a team of scientists within a week, but the Chinese government refused to let them in, which was a reason the US got a later start in identifying the danger of virus outbreak there and taking early action.[98][99]

On January 7, 2020, the Chinese health authorities confirmed that this cluster was caused by a novel infectious coronavirus.[3] On January 8, the CDC issued an official health advisory via its Health Alert Network (HAN) and established an Incident Management Structure to coordinate domestic and international public health actions.[100] On January 10 and 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued technical briefings warning about a strong possibility of human-to-human transmission and urging precautions.[101] On January 14, the WHO said "preliminary investigations conducted by the Chinese authorities have found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission," although it recommended that countries still take precautions due to the human-to-human transmission during earlier SARS and MERS outbreaks.[101]

The CDC issued an update on January 17, noting that person-to-person spread was not confirmed, but was still a possibility.[102] On January 20, it activated its Emergency Operations Center (EOC) to further respond to the outbreak in China.[103] The same day, the WHO and China confirmed that human-to-human transmission had occurred.[104]

On January 20, the first report of a COVID-19 case in the U.S. came in a man who returned on January 15 from visiting family in Wuhan, China, to his home in Snohomish County, Washington. He sought medical attention on January 19.[3] The second report came on January 24, in a woman who returned to Chicago, Illinois, on January 13 from visiting Wuhan.[2][4] The woman passed the virus to her husband, and he was confirmed to have the virus on January 30; at the time it was the first reported case of local transmission in the United States.[8] The same day, the WHO declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, warning that "all countries should be prepared for containment."[105][106][lower-alpha 4] The next day, January 31, the U.S. also declared a public health emergency.[108] Although by that date there were only seven known cases in the U.S., the HHS and CDC reported that there was a likelihood of further cases appearing in the country.[108]

February 2020

On February 2, the U.S. enacted travel restrictions to and from China.[14] Additional travel restrictions were placed on foreign nationals who had traveled within the past 14 days in certain countries, with exceptions for families and residents. Americans returning from those regions underwent health screenings and a 14-day quarantine.[109][110]

On February 6, the earliest confirmed American death occurred in Santa Clara County, California, of a 57-year-old woman.[9] It was later learned that nine deaths had occurred before February 6, as the virus had been circulating undetected in the U.S. before January, and possibly as early as November.[111]

On February 25, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned the American public for the first time to prepare for a local outbreak.[112] With no vaccine or treatment available, Americans were asked to prepare to take other precautions.[113] Meanwhile, large gatherings that occurred before widespread shutdowns and social distancing measures were put in place, including Mardi Gras in New Orleans on February 25, accelerated transmission.[114]

March 2020

.jpg)

On March 2, travel restrictions from Iran went into effect.[115] On March 7, the CDC warned that widespread disease transmission may force large numbers of people to seek healthcare, which could overload healthcare systems and lead to otherwise preventable deaths.[116] On March 11, the WHO declared the outbreak to be a pandemic.[27] By this time, the virus had spread to 110 countries and all continents except Antarctica.[117] The World Health Organization's definition of a pandemic "mixed severity and spread", reported Vox, and it held off calling the outbreak a pandemic because many countries at the time were reporting no spread or low spread.[118][119]

By March 12, diagnosed cases of COVID-19 in the U.S. exceeded a thousand.[120] On March 13, travel restriction for the 26 European countries that comprise the Schengen Area went into effect; restrictions for the United Kingdom and Ireland went into effect on March 16.[121] Also on March 16, the White House advised against any gatherings of more than ten people.[122] Since March 19, 2020, the State Department has advised U.S. citizens to avoid all international travel.[123]

By the middle of March, all fifty states were able to perform tests with a doctor's approval, either from the CDC or from commercial labs. However, the number of available test kits remained limited, which meant the true number of people infected had to be estimated.[124] On March 19, administration officials warned that the number of cases would begin to rise sharply as the country's testing capacity substantially increased to 50,000-70,000 tests per day.[125][126]

As cases began spreading throughout the nation, federal and state agencies began taking urgent steps to prepare for a surge of hospital patients. Among the actions was establishing additional places for patients in case hospitals became overwhelmed. The Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, for instance, was postponed to October and the fairgrounds where it is normally held was turned into a medical center.[127] Manpower from the military and volunteer armies were called up to help construct the emergency facilities.[128][129]

Throughout March and early April, several state, city, and county governments imposed "stay at home" quarantines on their populations to stem the spread of the virus.[130] By March 27, the country had reported over 100,000 cases.[131]

April 2020

On April 2, at President Trump's direction, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and CDC ordered additional preventive guidelines to the long-term care facility industry. They included requiring temperature checks for anyone in a nursing home, symptom screenings, and requiring all nursing home personnel to wear face masks. Trump also said COVID patients should have their own buildings or units and dedicated staffing teams.[132] On April 11, the U.S. death toll became the highest in the world when the number of cases reached 20,000, surpassing that of Italy.[133]

On April 19, the CMS added new regulations requiring nursing homes to inform residents, their families and representatives, of COVID-19 cases in their facilities.[134] On April 28, the total number of confirmed cases across the country surpassed one million.[135][136][137] On April 30, President Trump announced the administration was establishing a Coronavirus Commission for Safety and Quality in Nursing Homes.[138][139]

May to June 2020

The CDC prepared detailed guidelines for the reopening of businesses, public transit, restaurants, religious organizations, schools, and other public places. The Trump administration shelved the guidelines, but an unauthorized copy was published by the Associated Press on May 7.[140] Six flow charts were ultimately published on May 15,[141] and a 60-page set of guidelines was released without comment on May 20, weeks after many states had already emerged from lockdowns.[142]

By May 27, less than four months after the pandemic reached the U.S., 100,000 Americans had died from COVID-19.[143] State economic reopenings and lack of widespread mask orders resulted in a sharp rise in cases across most of the continental U.S. outside of the Northeast. By June 11, the number of cases in the U.S. had passed two million.[144]

July 2020 to present

By July 9, the number of cases had passed three million.[145] President Trump was first seen wearing a face mask in public on July 11, months after it had been recommended by public health experts.[146] By July 23, the number of cases had passed four million.[147] On July 29, the U.S. passed 150,000 deaths.[148] On August 9, the U.S. passed five million COVID-19 cases.[149]

In July, U.S. PIRG and 150 health professionals sent a letter asking the federal government to "shut it down now, and start over".[150] In July and early August, requests multiplied, with a number of experts asking for lockdowns of "six to eight weeks"[151] that they believed would restore the country by October 1, in time to reopen schools and have an in-person election. [152]

Preparations made after previous outbreaks

The United States has been subjected to pandemics and epidemics throughout its history, including the 1918 Spanish flu, the 1957 Asian flu, and the 1968 Hong Kong flu pandemics.[153][154][155] In the most recent pandemic prior to COVID-19, the 2009 swine flu pandemic took the lives of more than 12,000 Americans and hospitalized another 270,000 over the course of approximately one year.[153]

According to the Global Health Security Index, an American-British assessment which ranks the health security capabilities in 195 countries, the U.S. in 2020 was the "most prepared" nation.[156][157]

Reports predicting global pandemics

The United States Intelligence Community, in its annual Worldwide Threat Assessment report of 2017 and 2018, said if a related coronavirus were "to acquire efficient human-to-human transmissibility", it would have "pandemic potential". The 2018 Worldwide Threat Assessment also said new types of microbes that are "easily transmissible between humans" remain "a major threat".[158][159][160] Similarly, the 2019 Worldwide Threat Assessment warned that "the United States and the world will remain vulnerable to the next flu pandemic or large-scale outbreak of a contagious disease that could lead to massive rates of death and disability, severely affect the world economy, strain international resources, and increase calls on the United States for support."[160][161]

Preparations

In 2005, President George W. Bush began preparing a national pandemic response plan.[162] In 2006, the Department of Health and Human Services established a new division, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) to prepare for chemical, biological and nuclear attacks, as well as infectious diseases. In its first year of operation, BARDA "estimated that an additional 70,000 [ventilators] would be required in a moderate influenza pandemic"; a contract was let and work started, but no ventilators were ever delivered.[163]

A vaccine for a related coronavirus, SARS, was developed in the U.S. by 2016, but never progressed to human trials due to a lack of funding.[164] In January 2017, the U.S. government had updated its estimate of resource gaps, including ventilators, face masks, and hospital beds.[165] While some cities did take the risk of a pandemic seriously enough to prepare years ahead of time, there was often a failure to follow through due to financial constraints. New York City, for instance, took preparatory steps more than a decade ago, but then discontinued them in favor of other priorities.[166]

In 2017, outgoing Obama administration officials briefed incoming Trump administration officials on how to respond to pandemics by using simulated scenarios.[167] Obama's national security advisor Susan Rice met with her successor, General Michael Flynn, where she outlined the risk of a pandemic with a tabletop exercise and gave him a pandemic guidebook.[168]

The Trump administration simulated a series of pandemic outbreaks from China in 2019 and found that the U.S. government response was "underfunded, underprepared, and uncoordinated" (see Crimson Contagion).[169] Among the conclusions of the test was a shortage of certain medical supplies which are produced overseas, including N95 masks. President Trump responded to the simulation with an executive order to increase the availability and quality of flu vaccines, and the administration later increased funding for the pandemic threats program of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).[170] In September 2019, White House economists published a study that warned a pandemic could kill half a million Americans and devastate the economy.[171]

Reorganization and departures

In May 2018, National Security Advisor John Bolton reorganized the executive branch's United States National Security Council (NSC), largely merging the group responsible for global health security and biodefense—established by the Obama administration following the 2014 ebola epidemic—into a bigger group responsible for counter-proliferation and biodefense. Along with the reorganization, the leader of the global health security and biodefense group, Rear Admiral Timothy Ziemer, left to join another federal agency, while Tim Morrison became the leader of the combined group.[172][173] Critics of this reorganization referred to it as "disbanding" a pandemic preparedness group.[173][174] In July 2020, the administration planned to create a new pandemic preparedness office within the State Department.[175]

The administration had in the years before the coronavirus outbreak reduced the number of staff working in the Beijing office of the U.S. CDC from 47 to 14. One of the staff eliminated in July 2019 was training Chinese field epidemiologists to respond to disease outbreaks at their hotbeds. Also closed were single-person offices of Beijing's National Science Foundation (NSF), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and U.S. Department of Agriculture.[176]

The Trump Administration also ended funding for the PREDICT pandemic early-warning program in China, which trained and supported staff in 60 foreign laboratories, with field work ceasing September 2019.[177] The scientists tasked with identifying potential pandemics were already stretched too far and thin.[178]

Unsuccessful efforts to improve mask and ventilator supply

Since 2015, the federal government has spent $9.8 million on two projects to prevent a mask shortage but abandoned both projects before completion.[179] A second BARDA contract was signed with Applied Research Associates of Albuquerque, to design an N95-rated mask that could be reused in emergencies without reduced effectiveness. Though federal reports had called for such a project since 2006, the ARA contract was not signed until 2017, and missed its 15-month completion deadline, resulting in the 2020 pandemic reaching the United States before the design was ready.[179]

Previous respiratory epidemics and government planning indicated a need for a stockpile of ventilators that were easier for less-trained medical personnel to use. BARDA Project Aura issued a request for proposals in 2008, with a goal of FDA approval in 2010 or 2011. A contract for the production of up to 40,000 ventilators was awarded to Newport Medical Instruments, a small ventilator manufacturer, with a target price of $3,000, much lower than more complicated machines costing more than $10,000, and it produced prototypes with target FDA approval in 2013. Covidien purchased NMI and after requesting more money to complete the project (bringing the total cost to around $8 million) asked the government to cancel the contract, saying it was not profitable.[180] The government awarded a new $13.8 million contract to Philips, in 2014. The design for the Trilogy Evo Universal gained FDA approval in July 2019. The government ordered 10,000 ventilators in September 2019, with a mid-2020 deadline for the first deliveries and a deadline of 2022 to complete all 10,000. Despite the start of the epidemic in December, the capacity of the company to have produced enough to fill the full order, and the ability of the government to force faster production, the government did not reach an agreement with Philips for accelerated delivery until March 10, 2020.[180][181] By mid-March, the need for more ventilators had become immediate, and even in the absence of any government contracts, other manufacturers announced plans to make many tens of thousands.[182] In the meantime, Philips had been selling a commercial version, the Trilogy Evo, at much higher prices,[181] leaving only 12,700 in the Strategic National Stockpile as of March 15.[180]

Compared to the small amount of money spent on recommended supplies for a pandemic, billions of dollars had been spent by the Strategic National Stockpile to create and store a vaccine for anthrax, and enough smallpox inoculations for the entire country.[183]

Potential response strategies

In 2016, the NSC laid out pandemic strategies and recommendations including moving swiftly to fully detect potential outbreaks, securing supplemental funding, considering invoking the Defense Production Act, and ensuring sufficient protective equipment available for healthcare workers. The Trump administration was briefed on it in 2017, but declined to make it official policy.[184]

Responses

Medical response

Attempts to assist China and Iran

On January 6, a week after the U.S. was informed about the outbreak in China, both the Health and Human Services department and the CDC offered to send a team of U.S. health experts to China multiple times but were ignored.[12][185] For all of January, China reported shortages of test equipment and hospital facilities in Wuhan.[186][187] Nonetheless, according to CDC Director Dr. Robert Redfield, the director of the CDC, the Chinese government refused to let them in, which contributed to the U.S. getting a late start in identifying the danger of their outbreak and containing it before it reached other countries.[98] U.S. Health Secretary Alex Azar said that while China did notify the world much sooner than it had after their SARS outbreak in 2003, after which the CDC committed over 800 of its medical experts to quickly contain that virus, it was unexplainably turning away CDC help for this new outbreak.[188][189]

On January 28, the CDC updated its China travel recommendations to level 3, its highest alert.[12] Alex Azar submitted names of U.S. experts to the WHO and said the U.S. would provide $105 million in funding, adding that he had requested another $136 million from Congress.[190][189] On February 8, the WHO's director-general announced that a team of international experts had been assembled to travel to China and he hoped officials from the CDC would also be part of that mission.[191][189] The WHO team consisted of 13 international researchers, including two Americans, and toured five cities in China with 12 local scientists to study the epidemic from February 16–23.[192] The final report was released on February 28.[193]

In late January, a number of U.S. organizations began sending personal protective equipment to China. Boeing announced a donation of 250,000 medical masks to help address China's supply shortages,[194] while the United Church of Christ (UCC) and American Baptist Churches USA joined an ecumenical effort of American churches to provide much-needed medical supplies to China.[195]

On February 7, The State Department said it had facilitated the transportation of nearly eighteen tons of medical supplies to China, including masks, gowns, gauze, respirators, and other vital materials.[196] On the same day, U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo announced a $100 million pledge to China and other countries to assist with their fights against the virus.[197] On March 21, China said it had not received epidemic funding from the U.S. government and said so again on April 3.[198]

On February 28, the State Department offered to help Iran fight its own outbreak, as Iran's cases and deaths were dramatically increasing.[199][200]

Testing

.jpg)

.jpg)

Beyond identifying whether a person is currently infected, coronavirus testing helps health professionals ascertain how bad the epidemic is and where it is worst.[201] However, the accuracy of national statistics on the number of cases and deaths from the outbreak depend on knowing how many people are being tested every day, and how the available tests are being allocated.[202]

While the WHO opted to use an approach developed by Germany to test for coronavirus, the United States developed its own testing approach. The German testing method was made public on January 13, and the American testing method was made public on January 28. The WHO did not offer any test kits to the U.S. because the U.S. normally had the supplies to produce their own tests.[203]

The United States had a slow start in widespread coronavirus testing.[204][205] From the start of the outbreak until early March 2020, the CDC gave restrictive guidelines on who should be eligible for COVID-19 testing. The initial criteria were (a) people who had recently traveled to certain countries, or (b) people with respiratory illness serious enough to require hospitalization, or (c) people who have been in contact with a person confirmed to have coronavirus.[21]

In February, the U.S. CDC produced 160,000 coronavirus tests, but soon it was discovered that many were defective and gave inaccurate readings.[18][206] On February 19, the first U.S. patient with COVID-19 of unknown origin (a possible indication of community transmission) was hospitalized. The patient's test was delayed for four days because he had not qualified for a test under the initial federal testing criteria.[207] By February 27, fewer than 4,000 tests had been conducted in the U.S.[18] Although academic laboratories and hospitals had developed their own tests, they were not allowed to use them until February 29, when the FDA issued approvals for them and private companies.[18][208]

From February 25, a group of researchers from the Seattle Flu Study defied federal and state officials to conduct their own tests, using samples already collected from flu study subjects who had not given permission for coronavirus testing. They quickly found a teenager infected with SARS-CoV-2 of unknown origin, newly indicating that an outbreak had already been occurring in Washington for the past six weeks. State regulators stopped these researchers' testing on March 2, although the testing later resumed through the creation of the Seattle Coronavirus Assessment Network.[209][210]

On March 5, the CDC relaxed the criteria to allow doctors discretion to decide who would be eligible for tests.[21] Also on March 5, Vice President Mike Pence, the leader of the coronavirus response team, acknowledged that "we don't have enough tests" to meet the predicted future demand; this announcement came only three days after FDA commissioner Stephen Hahn committed to producing nearly a million tests by that week.[211] Senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut and Representative Stephen Lynch of Massachusetts both noted that as of March 8 their states had not yet received the new test kits.[212][213] By March 11, the U.S had tested fewer than 10,000 people.[214] Doctor Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, acknowledged on March 12 it was "a failing" of the U.S. system that the demand for coronavirus tests was not being met;[215] Fauci later clarified that he believed the private sector should have been brought in sooner to address the shortfall.[216]

By mid-March, the U.S. had tested 125 people per million of their population, which was lower than several other countries.[217] The first COVID-19 cases in the U.S. and South Korea were identified at around the same time.[218] Critics say the U.S. government has botched the approval and distribution of test kits, losing crucial time during the early weeks of the outbreak, with the result that the true number of cases in the United States was impossible to estimate with any reasonable accuracy.[124][219]

By March 12, all 50 states were able to perform tests, with a doctor's approval, either from the CDC or local commercial lab.[220] This was followed by the government announcing a series of measures intended to speed up testing. These measures included the appointment of Admiral Brett Giroir of the U.S. Public Health Service to oversee testing, funding for two companies developing rapid tests, and a hotline to help labs find needed supplies.[221] The FDA also gave emergency authorization for New York to obtain an automated coronavirus testing machine.[222]

In a March 13 press conference, the Trump administration announced a campaign to conduct tests in retail store parking lots across the country,[223] but this was not widely implemented.[224]

On March 13, drive-through testing in the U.S. began in New Rochelle, Westchester County, as New Rochelle was the U.S. town with the most diagnosed cases at that time.[225] By March 22, drive-through testing had started in more than thirty states, although the Associated Press reported that "the system has been marked by inconsistencies, delays, and shortages," leading to many people waiting hours or days even though they showed symptoms and were recommended by a doctor to get a test. A lack of supplies had already forced the closure of drive-through testing in seven states.[226]

By March 30, more than a million people had been tested,[227] but not all the people showing symptoms were being tested.[228][229][215][230] During the weeks of April 6 and 13, the U.S. conducted about 150,000 tests per day, while experts recommended at least 500,000 per day prior to ending social distancing, with some recommending several times that level. Building up both testing and surveillance capacity are important to re-opening the economy; the purpose of social distancing is to buy time for such capacity-building.[231]

The New York Times reported on April 26 that the U.S. still had yet to reach an adequate level of testing capacity needed to monitor and contain outbreaks. The capacity has been hampered by shortages of reagents, shortages of test kits components like nasal swabs, shortages of protective gear for health workers, limited laboratory workers and equipment, and the federal government's limited interventions to solve shortages, instead of leaving the issue to the free market, causing states and hospitals to compete with each other for supplies.[232]

By early May, the U.S. was testing around 240,000 to 260,000 people per day, but this was still an inadequate level to contain the outbreak.[26][233][234][235]

By June 24, 13 of the 41 federally funded community-based testing sites originally established in March were set to lose federal funding. They will remain under state and local control. Trump administration testing czar Admiral Giroir described the original community-based testing program as "antiquated".[236] By June 26, 2020, Dr. Fauci said the administration was considering pooled testing as a way to speed up testing.[237]

Contact tracing

Contact tracing is a tool to control transmission rates during the reopening process. Some states like Texas and Arizona opted to proceed with reopening without adequate contact tracing programs in place. Health experts have expressed concerns about training and hiring enough personnel to reduce transmission. Privacy concerns have prevented measures such as those imposed in South Korea where authorities used cellphone tracking and credit card details to locate and test thousands of nightclub patrons when new cases began emerging.[238] Funding for contact tracing is thought to be insufficient, and even better-funded states have faced challenges getting in touch with contacts. Congress has allocated $631 million for state and local health surveillance programs, but the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security estimates that $3.6 billion will be needed. The cost rises with the number of infections, and contact tracing is easier to implement when the infection count is lower. Health officials are also worried that low-income communities will fall further behind in contact tracing efforts which "may also be hobbled by long-standing distrust among minorities of public health officials".[239]

As of July 1, only four states are using contact tracing apps as part of their state-level strategies to control transmission. The apps document digital encounters between smartphones, so the users will automatically be notified if someone they had contact with has tested positive. Public health officials in California claim that most of the functionality could be duplicated by using text, chat, email and phone communications.[240]

Drug therapy and vaccine development

.jpg)

There is currently no drug therapy or vaccine approved for treating COVID-19, nor is there any clear evidence that COVID-19 infection leads to immunity (although experts assume it does for some period).[241] As of late March 2020, more than a hundred drugs were in testing.[242]

In early March, President Trump directed the FDA to test certain medications to discover if they had the potential to treat COVID-19 patients.[243] Among those were chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, which have been successfully used to treat malaria for over 50 years. A small test in France had apparently given good results[244] and they were being tested in a European Union-wide clinical trial.[245] Some U.S. physicians, under the compassionate use and Emergency Use Authorization exceptions by the FDA, have prescribed them while trials and analysis are still ongoing.[243][246][247]

In April 2020, the CDC began testing blood samples to determine if a person has been exposed to the virus, even without showing symptoms, which could provide information about immunity.[248]

On July 1, 2020, the FDA updated its advice and cautioned against the use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 outside of a hospital or clinical trial due to heart risk, but maintained its approved use for malaria, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis.[249] In a study of 1446 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 published June 18, 2020, hydroxychloroquine was found to not have a significant beneficial or adverse effect.[250] However, in a study of 2,541 patients admitted to hospitals for COVID-19, published July 1, 2020, the use of hydroxychloroquine with and without azithromycin resulted in a significant reduction of deaths.[251][252][253]

There is no vaccine for coronavirus as of July 2020, however, research is ongoing in a number of countries to create one.[254] More than 70 companies and research teams are working on a vaccine, with five or six operating primarily in the U.S.[255] Contributing funds to the research is Bill Gates, whose foundation is focusing entirely on the pandemic, and he anticipates a vaccine could be ready by April 2021.[256] In preparation for large-scale production, Congress set aside more than $3.5 billion for this purpose as part of the CARES Act.[257][255] Among the labs working on a vaccine is the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, which has previously studied other infectious diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and MERS. By March 18, tests had begun with dozens of volunteers in Seattle, Washington, which was sponsored by the U.S. government. Similar safety trials of other coronavirus vaccines will begin soon in the U.S.[258] This search for a vaccine has taken on aspects of national security and global competition.[259]

On August 5, 2020, the United States agreed to pay Johnson and Johnson more than $1 billion to create 100 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine. The deal gave the US an option to order an additional 200 million doses. The doses were supposed to be provided for free to Americans if they are used in a COVID-19 vaccination campaign.[260]

Medical supplies

.png)

The first known case of COVID-19 in the U.S. was confirmed by the CDC on January 21, 2020.[261] The next day, the owner of the medical supply company Prestige Ameritech wrote to HHS officials to say he could produce millions of N95 masks per month, but the government was not interested. In a follow-up letter on January 23, the business owner informed the government that "We are the last major domestic mask company," without success.[262]

Trump administration officials declined an offer for congressional coronavirus funding on February 5. The officials, including HHS Secretary Alex Azar, "didn't need emergency funding, that they would be able to handle it within existing appropriations," Senator Chris Murphy recalled.[263] On February 7 Mike Pompeo announced the administration donated more than 35,000 pounds of "masks, gowns, gauze, respirators, and other vital materials" to China the same day the WHO warned about "the limited stock of PPE (personal protective equipment)".[261]

In early March, the country had about twelve million N95 masks and thirty million surgical masks in the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS), but the DHS estimated the stockpile had only 1.2% of the roughly 3.5 billion masks that would be needed if COVID-19 were to become a "full-blown" pandemic.[264] As of March, the SNS had more than 19,000 ventilators (16,660 immediately available and 2,425 in maintenance), all of which dated from previous administrations.[265] A previous 2015 CDC study found that seven billion N95 respirators might be necessary to handle a "severe respiratory outbreak".[266] Vessel manifests maintained by U.S. Customs and Border Protection showed a steady flow of the medical equipment needed to treat the coronavirus being shipped abroad as recently as March 17. Meanwhile FEMA said the agency "has not actively encouraged or discouraged U.S. companies from exporting overseas" and asked USAID to send back its reserves of protective gear for use in the U.S.[267][268] President Trump evoked the Defense Production Act to prohibit some medical exports.[269] Some analysts warned that export restrictions could cause retaliation from countries that have medical supplies the United States needs to import.[270]

.jpg)

Some states had immediate needs for ventilators; hospitals in New York City, for example, ran out.[271][272] By the end of March, states were in a bidding war against each other and the federal government for scarce medical supplies such as N95 masks, surgical masks, and ventilators.[273][274][22] Meanwhile, as States scrambled to purchase supplies at inflated prices from third party distributors (some of which later turned out to be defective), hundreds of tons of medical-grade face masks were shipped by air freight to foreign buyers in China and other countries.[275] In February, the Department of Commerce published a guidance advising U.S. firms on compliance with Beijing's fast-track process for the sale of "critical medical products", which required the masks shipped overseas meet U.S. regulatory standards.[276][277] According to Chinese customs disclosures, over 600 tons of face masks were shipped to China in February. Rick Bright, a federal immunologist and whistleblower testified in May that the federal government had not taken proper action to acquire the needed supplies.[275]

Medical organizations such as the American Medical Association and American Nurses Association implored Trump to obtain medical supplies, because they were "urgently needed".[278][279] That led President Trump to sign an order setting motion parts of the Defense Production Act, first used during the Korean War, to allow the federal government a wide range of powers, including telling industries on what to produce, allocating supplies, giving incentives to industries, and allowing companies to cooperate.[280][281] Trump then ordered auto manufacturer General Motors to make ventilators.[23]

During this period, hospitals in the U.S. and other countries were reporting shortages of test kits, test swabs, masks, gowns and gloves, referred to as PPE.[282][283][284] The Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released a report regarding their March 23–27 survey of 323 hospitals. The hospitals reported "severe shortages of testing supplies", "frequently waiting 7 days or longer for test results", which extended the length of patient stays, and as a result, "strained bed availability, personal protective equipment (PPE) supplies, and staffing". The hospitals also reported, "widespread shortages of PPE" and "changing and sometimes inconsistent guidance from federal, state and local authorities".[285] At a press briefing following the release of the report President Trump called the report "wrong" and questioned the motives of the author. Later he called the report "another fake dossier".[24]

In early April, there was a widespread shortage of PPE, including masks, gloves, gowns, and sanitizing products.[286] The difficulties in acquiring PPE for local hospitals led to orders for gowns and other safety items being confiscated by FEMA and diverted to other locations, which meant that in some cases states had to compete for the same PPE.[287] The shortages led in one instance of a governor asking the New England Patriots of the NFL to use their private plane to fly approximately 1.2 million masks from China to Boston.[288] At that time, Veterans Affairs (VA) employees said nurses were having to use surgical masks and face shields instead of more protective N95 masks.[289]

An unexpectedly high percentage of COVID-19 patients in the ICU required dialysis as a result of kidney failure, about 20%.[290] In mid-April, employees at some hospitals in New York City reported not having enough dialysis machines, were running low on fluids to operate the machines, and reported a shortage of dialysis nurses as many were out sick with COVID-19 due to lack of sufficient PPE.[290][291][292]

Exceeding hospital capacity

Uncontrolled community spread led some medical facilities to refuse new patients or start transferring patients out. In March and April, this happened in the Detroit, Michigan area[293] and New York City area;[294] Yakima, Washington in June;[295] and in July it happened in Houston,[296] the Boise, Idaho area,[297] Lake Charles and Lafayette, Louisiana,[298] and at dozens of hospitals across Florida.[299] By August, some hospitals in Mississippi were transferring patients out of state.[300]

Arizona declared crisis standards of care in July 2020, allowing hospitals to legally provide treatment normally considered substandard to some patients in order to save others.[301]

Measuring case and mortality rates

By March 26, the United States, with the world's third-largest population, surpassed China and Italy as the country with the highest number of confirmed cases in the world.[302] By April 25, the U.S. had over 905,000 confirmed coronavirus cases and nearly 52,000 deaths, giving it a mortality rate around 5.7 percent. (In comparison, Spain's mortality rate was 10.2 percent and Italy's was 13.5 percent.)[303][37] At that time, more than 10,000 American deaths had occurred in nursing homes. Most nursing homes did not have easy access to testing, making the actual number unknown.[304] Subsequently, a number of states including Maryland[305] and New Jersey[306] reported their own estimates of deaths at nursing homes, ranging from 20 to 50 percent of the states' total deaths.

Several serological antibody studies suggest both that the number of infections is far higher than officially reported, and that the true case fatality rate is far lower.[307][308][309][310]

In counting actual confirmed cases, some have questioned the reliability of totals reported by different countries. Measuring rates reported by countries such as China or Iran have been questioned as potentially inaccurate.[311] In mid-April 2020, China revised its case totals much higher and its death toll up by 50% for Wuhan, partly as a result of a number of countries having questioned China's official numbers.[312] Iran's rates have also been disputed, as when the WHO's reports about their case counts were contradicted by top Iranian health officials.[313] Within the U.S., there are also discrepancies in rates between different states. After a group of epidemiologists requested revisions in how the CDC counts cases and deaths, the CDC in mid-April updated its guidance for counting COVID-19 cases and deaths to include both confirmed and probable ones, although each state can still determine what to report.[314] Without accurate reporting of cases and deaths, however, epidemiologists have difficulty in guiding government response.[315]

Federal, state, and local governments

The federal government of the United States responded to the pandemic with various declarations of emergency, which resulted in travel and entry restrictions. They also imposed guidelines and recommendations regarding the closure of schools and public meeting places, lockdowns, and other restrictions intended to slow the progression of the virus, which state, territorial, tribal, and local governments have followed.

Effective July 15, 2020, the default data centralization point for COVID-19 data in the U.S. is switching from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to Department of Health and Human Services.[316][317][318] However, "hospitals may be relieved from reporting directly to the Federal Government if they receive a written release from the State stating the State will collect the data from the hospitals and take over Federal reporting."[316]

Military

.jpg)

On February 3, an unclassified Army briefing document on the coronavirus projected that in an unlikely "black swan" scenario, "between 80,000 and 150,000 could die." The black swan theory correctly stated that asymptomatic people could "easily" transmit the virus, a belief that was presented as outside medical consensus at the time of the briefing. The briefing also stated that military forces could be tasked with providing logistics and medical support to civilians, including "provid[ing] PPE (N-95 Face Mask, Eye Protection, and Gloves) to evacuees, staff, and DoD personnel".[319]

In mid-March, the government began having the military add its health care capacity to impacted areas. The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), under the authority of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), leased private buildings nationwide. They included hotels, college dormitories, and larger open buildings, which were converted into temporary hospitals. The Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in New York City was quickly transformed into a 2,000-bed care facility on March 23, 2020.[320]The Army also set up field hospitals in various affected cities.[321]

Some of these facilities had ICUs for Covid patients, while others served non-coronavirus patients to allow established hospitals to concentrate on the pandemic.[322][321] At the height of this effort, U.S. Northern Command had deployed 9000 military medical personnel.[321] As of July 2020 additional Reserve personnel are on 'prepare-to-deploy orders' to Texas and California.[321]

In addition to the many popup hospitals nationwide, the Navy on March 18 deployed two hospital ships, USNS Mercy and USNS Comfort, which were planned to accept non-coronavirus patients transferred from land-based hospitals, so those hospitals could concentrate on virus cases.[323] On March 29, citing reduction in on-shore medical capabilities and the closure of facilities at the Port of Miami to new patients, the U.S. Coast Guard required ships carrying more than fifty people to prepare to care for sick people onboard.[324][325]

The Army announced on April 6 that basic training would be postponed for new recruits. Recruits already in training would continue what the Army is calling "social-distanced-enabled training".[326] However, the military, in general, remained ready for any contingency in a COVID-19 environment. By April 9, nearly 2,000 service members had confirmed cases of COVID-19.[327]

In April, the Army made plans to resume collective training.[328] Social distancing of soldiers is in place during training, assemblies,[329] and transport between locations.[330] Temperatures of the soldiers are taken at identified intervals, and measures are taken to immediately remediate affected soldiers.[331][332][333][334]

On June 26, 2020, the VA reported 20,509 cases of COVID-19 and 1,573 deaths among patients (plus more than two thousand cases and 38 deaths among its own employees).[335]

Private sectors

Many janitors and other cleaners throughout the United States have reported that they are afforded completely inadequate time and resources to clean and to disinfect for COVID-19. Many office cleaners reported that they are given insufficient time for cleaning and no training on how to disinfect COVID-19. Airlines often allot ten minutes to clean an entire airplane between arrival and departure, and cleaners are unable to disinfect even close to all the tray tables and bathrooms. Often, cleaners are not told where workers who test positive for COVID-19 are working; cleaning cloths and wipes are re-used, and disinfecting agents, such as bleach, are not provided. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the federal agency that regulates workplace safety and health, investigate but a small fraction of COVID-19 complaints. Mary Kay Henry, president of Service Employees International Union (a trade union which represents 375,000 American custodians), explained that "reopenings happened across the country without much thoughtfulness for cleaning standards." She urges better government standards and a certification system.[336]

Public response

Polling showed a significant partisan divide regarding the outbreak.[337] NPR, PBS NewsHour, and Marist found in their mid-March survey that 76% of Democrats viewed COVID-19 as "a real threat", while only 40% of Republicans agreed; the previous month's figures for Democrats and Republicans were 70% and 72%, respectively.[338] A mid-March poll conducted by NBC News and The Wall Street Journal found that 60% of Democrats were concerned someone in their family might contract the virus, while 40% of Republicans expressed concern. Nearly 80% of Democrats believed the worst was yet to come, whereas 40% of Republicans thought so. About 56% of Democrats believed their lives would change in a major way due to the outbreak, compared to 26% for Republicans.[339] A mid-March poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 83% of Democrats had taken certain precautions against the virus, compared to 53% of Republicans. The poll found that President Trump was the least-trusted source of information about the outbreak, at 46% overall, after the news media (47%), state and local government officials (70%), WHO (77%), and CDC (85%). 88% of Republicans expressed trust in the President; 69% of Democrats expressed trust in the media.[340] A CNBC/Change Research Poll conducted in early May—in six states where the November election was expected to be close—found that 97% of Democrats but only 39% of Republicans were "seriously concerned" about the outbreak, and similarly that Democrats were far more likely to report taking health precautions.[341]

The outbreak prompted calls for the United States to adopt social policies common in other wealthy countries, including universal health care, universal child care, paid sick leave, and higher levels of funding for public health.[342][343][344]

.jpg)

Political analysts anticipated it may negatively affect Trump's chances of re-election.[346][347] In March 2020, when "social distancing" practices began, the governors of many states experienced sharp gains in approval ratings,[348] and Trump's approval rating increased from 44% to 49% in Gallup polls,[349] although it then fell to 43% by mid-April. At that time, Pew Research polls indicated that 65% of Americans felt Trump was too slow in taking major steps to respond to the coronavirus outbreak.[350] An April 21 Washington Post-University of Maryland poll found a 44% approval rate for the president's handling of the pandemic, compared to 72% approval for state governors.[351] A mid-April poll by the Associated Press and NORC at the University of Chicago estimated that President Trump was a source of information on the pandemic for 28% of Americans, while state or local governments were a source for 50% of Americans. 60% of Americans felt Trump was not listening enough to health experts in dealing with the outbreak.[352][353]

Beginning in mid-April 2020, there were protests in several U.S. states against government-imposed lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.[354][355] The protests, mostly organized by conservative groups and individuals,[356][357] decried the economic and social impact of stay-at-home orders, business closures, and restricted personal movement and association, and demanded that their respective states be "re-opened" for normal business and personal activity.[358]

The protests made international news[359][360] and were widely condemned as unsafe and ill-advised.[361] They ranged in size from a few hundred people to several thousand, and spread on social media with encouragement from U.S. President Donald Trump.[362]

By May 1, there had been demonstrations in more than half of the states; many governors began to take steps to lift the restrictions as daily new infections began decreasing due to social distancing measures.[363]On April 16, Pew Research polls indicated that 32% of Americans worried state governments would take too long to re-allow public activities, while 66% feared the state restrictions would be lifted too quickly.[364]

A poll conducted from May 7 to 10 by SRSS, for CNN, concluded that 54% of people in the U.S. felt the federal government was doing a poor job in stopping the spread of COVID-19 in the country. 57% felt the federal government was not doing enough to address the limited availability of COVID-19 testing. 58% felt the federal government was not doing enough to prevent a second wave of COVID-19 cases later in 2020.[365] A poll conducted from May 20 and 21 by Yahoo News and YouGov found that 56% of the American public were "very" concerned about "false or misleading information being communicated about coronavirus", while 30% were "somewhat" concerned. 56% of Democrats said the top source of false or misleading information about the coronavirus was the Trump administration, while 54% of Republicans felt the media was the top source of false or misleading information. Regarding a debunked conspiracy theory that philanthropist Bill Gates was planning to use mass COVID-19 vaccinations to implant microchips into people to track them, 44% of Republicans believed the conspiracy theory, as did 19% of Democrats.[366]

Starting in late May, large-scale protests against police brutality in at least 200 U.S. cities in response to the killing of George Floyd raised concerns of a resurgence of the virus due to the close proximity of protesters.[367] Doctor Fauci said it could be a "perfect set-up for the spread of the virus".[368] Fauci also said, "Masks can help, but it's masks plus physical separation."[369]

A 2020 study using both GPS location data and surveys found that Republicans engaged in less social distancing than Democrats during the pandemic.[370]

Impacts

Economic

The pandemic, along with the resultant stock market crash and other impacts, has led a recession in the United States following the economic cycle peak in February 2020.[371] The economy contracted 4.8 percent from January through March 2020,[372] and the unemployment rate rose to 14.7 percent in April.[373] The total healthcare costs of treating the epidemic could be anywhere from $34 billion to $251 billion according to analysis presented by The New York Times.[374] A study by economists Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson indicated that most economic impact due to consumer behavior changes was prior to mandated lockdowns.[375]

| Variable | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | June | July |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jobs, level (000s)[376] | 152,463 | 151,090 | 130,303 | 133,002 | 137,802 | 139,582 |

| Jobs, monthly change (000s)[376] | 251 | -1,373 | -20,787 | 2,699 | 4,800 | 1,780 |

| Unemployment rate %[377] | 3.5% | 4.4% | 14.7% | 13.3% | 11.1% | 10.2% |

| Number unemployed (millions)[378] | 5.8 | 7.1 | 23.1 | 21.0 | 17.8 | 16.3 |

| Employment to population ratio %, age 25-54[379] | 80.5% | 79.6% | 69.7% | 71.4% | 73.5% | 73.8% |

| Inflation rate % (CPI-All)[380] | 2.3% | 1.5% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.7% | 1.0% |

| Stock market S&P 500 (avg. level)[381] | 3,277 | 2,652 | 2,762 | 2,920 | 3,105 | 3,230 |

| Debt held by public ($ trillion)[382] | 17.4 | 17.7 | 19.1 | 19.9 | 20.5 | 20.6 |

Social

The pandemic has had far-reaching consequences that go beyond the spread of the disease itself and efforts to quarantine it, including political, cultural, and social implications.

Elections

The pandemic prompted calls from voting rights groups and some Democratic Party leaders to expand mail-in voting. Republican leaders generally opposed the change, though Republican governors in Nebraska and New Hampshire adopted it. Some states were unable to agree on changes, and a lawsuit in Texas resulted in a ruling (which is under appeal) that would allow any voter to mail in a ballot.[383] Responding to Democratic proposals for nation-wide mail-in voting as part of a coronavirus relief law, President Trump said "you'd never have a Republican elected in this country again" despite evidence the change would not favor any particular group.[384] Trump called mail-in voting "corrupt" and said voters should be required to show up in person, even though, as reporters pointed out, he had himself voted by mail in the last Florida primary.[385] Though vote fraud is slightly higher than in-person voter fraud, both instances are rare, and mail-in voting can be made more secure by disallowing third parties to collect ballots and providing free drop-off locations or prepaid postage.[386] April 7 elections in Wisconsin were impacted by the pandemic. Many polling locations were consolidated, resulting in hours-long lines. County clerks were overwhelmed by a shift from 20 to 30% mail-in ballots to about 70%, and some voters had problems receiving and returning ballots in time. Despite the problems, turnout was 34%, comparable to similar previous primaries.[387]

Statistics

The CDC publishes official numbers every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, reporting several categories of cases: individual travelers, people who contracted the disease from other people within the U.S., and repatriated citizens who returned to the U.S. from crisis locations, such as Wuhan, where the disease originated, and the cruise ship Diamond Princess.[388]

However, multiple sources note that statistics on confirmed coronavirus cases are misleading, since the shortage of tests means the actual number of cases is much higher than the number of cases confirmed.[389][230] The number of deaths confirmed to be due to coronavirus is likely to be an undercount for the same reason.[390][391][392][393] Conversely, deaths of people who had underlying conditions may lead to overcounting.[394]

Excess mortality[395] comparing deaths for all causes versus the seasonal average is more reliable.[396] It counts additional deaths which are not explained by official reported coronavirus mortality statistics.[397] On the other hand, it may include deaths due to strained healthcare systems, bans on elective surgery, or by policies aimed at curtailing the epidemic.[398] The CDC says it will issue an official estimate of coronavirus deaths in 2021—current estimates may not be reliable.[390]

The following numbers are based on CDC data, which is incomplete. In most U.S. locations, testing for some time was performed only on symptomatic people with a history of travel to Wuhan or with close contact to such people.[399][400][401] CDC testing protocols did not include non-travelling patients with no known contact with China until February 28.[402]

The original CDC-developed tests sent out on February 5 turned out to be faulty.[403] The faulty test produced a false positive from ordinary running water; a newer version is accurate and reliable.[169] On February 29, the FDA announced that labs would be allowed to do their own in-house testing immediately, independently of CDC testing, as long as they complete an emergency use authorization (EUA) within 15 days.[403]

Maps

.svg.png) Map of states and territories in the U.S. with number of confirmed cases as of August 15, 2020None confirmed<6,250 confirmed>6,250 confirmed>25,000 confirmed>100,000 confirmed>400,000 confirmed

Map of states and territories in the U.S. with number of confirmed cases as of August 15, 2020None confirmed<6,250 confirmed>6,250 confirmed>25,000 confirmed>100,000 confirmed>400,000 confirmed.svg.png) Map of states and territories in the U.S. with number of confirmed deaths as of August 14, 2020None confirmed<125 confirmed>125 confirmed>500 confirmed>2,000 confirmed>8,000 confirmed>32,000 confirmed

Map of states and territories in the U.S. with number of confirmed deaths as of August 14, 2020None confirmed<125 confirmed>125 confirmed>500 confirmed>2,000 confirmed>8,000 confirmed>32,000 confirmed Confirmed COVID-19 cases by county (as of August 14, 2020)

Confirmed COVID-19 cases by county (as of August 14, 2020)

Number of U.S. cases by date

> 100,000 cases:

50,000–100,000 cases:

Progression charts

No. of new daily cases (also in covidtracking.com and Worldometers), with a seven-day moving average:

No. of new daily deaths (also in covidtracking.com and Worldometers), with a seven-day moving average:

The plots above are charts showing the number of COVID-19 cases, deaths, and recoveries in the U.S. since February 26, 2020. The plot below uses a log scale for all four y axes on one plot to show relationships between the trends. On a log scale, data that shows exponential growth will plot as a more-or-less straight line. Each major division is a factor of 10. This makes the slope of the plot the relative rate of change anywhere in the timeline, which allows comparison of one plot with the others throughout the pandemic.

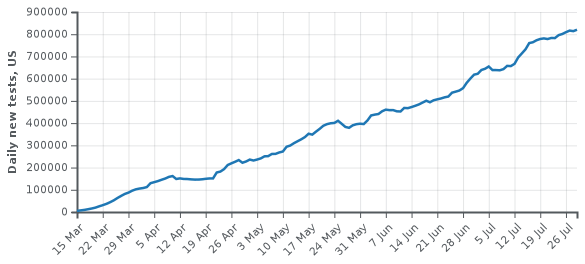

Daily new tests from Our World in Data, from owid-covid-data.csv owid/covid-19-data (chart, pop-adjusted chart), smoothed via 7-day moving average:

Test positivity rate for the U.S., calculated from Our World in Data (OWID), from owid-covid-data.csv owid/covid-19-data (chart), smoothed via 7-day moving average:

Test positivity rate is the ratio of positive tests to all tests made on the day. Charts of test positivity rate on U.S. state level are available in coronavirus.jhu.edu.

As of July 19, 2020, maximum test positivity rates on state-level (7-day average) are 23.6% for Arizona, 19.1% for Nevada and 18.7% for Florida Track Testing Trends.

An up-to-date hospitalization chart is available at covidtracking.com. A map in which progression charts for current hospitalizations per state are available on mouseover is available in Currently Hospitalized by State, covidtracking.com.

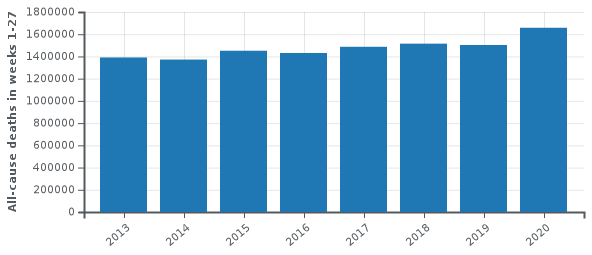

Weekly all-cause deaths in the U.S. based on CDC data Excess Deaths Associated with COVID-19:

Weekly all-cause deaths in the U.S., based on mortality.org data, stmf.csv :

mortality.org indicates the data for 2020 to be preliminary; above, the last two weeks available from mortality.org were excluded to prevent the worst effect of registration delay.

Weekly all-cause deaths in the U.S. for 0-14 year olds, based on mortality.org data, stmf.csv :

mortality.org indicates the data for 2020 to be preliminary; above, the last two weeks available from mortality.org were excluded to prevent the worst effect of registration delay.

All-cause deaths in the U.S. in weeks 1-27, year by year, based on mortality.org data, stmf.csv:

mortality.org indicates the data for 2020 to be preliminary; above, the last two weeks available from mortality.org were excluded to prevent the worst effect of registration delay. The above is not adjusted by population size.

Demographics

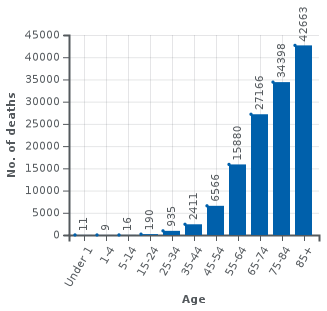

No. of COVID-19 deaths by age on July 22 Provisional COVID-19 Death Counts by Sex, Age, and State | Data | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

| Age group | Death count | Death percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All ages | 130,245 | 100% | |

| Under 1y | 11 | 0.008% | |

| 1-4y | 9 | 0.007% | |

| 5-14y | 16 | 0.012% | |

| 15-24y | 190 | 0.15% | |

| 25-34y | 935 | 0.72% | |

| 35-44y | 2,411 | 1.85% | |

| 45-54y | 6,566 | 5.04% | |

| 55-64y | 15,880 | 12.19% | |

| 65-74y | 27,166 | 20.86% | |

| 75-84y | 34,398 | 26.41% | |

| 85y and over | 42,663 | 32.76% | |

| Source: U.S. CDC,[404] 2020/07/22. | |||

Mortality rates

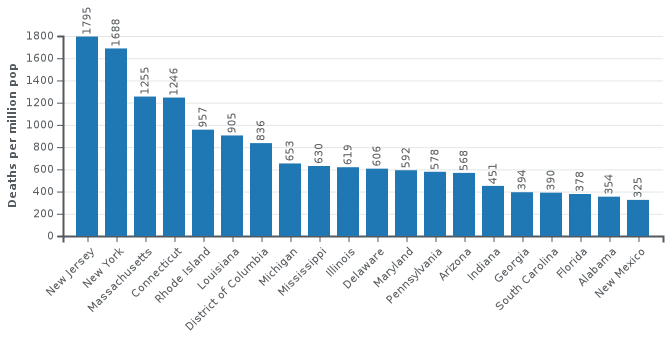

Top 20 mortality rates in U.S. states, that is, covid-coded deaths per million pop, August 9 Coronavirus Updates (COVID-19) Deaths & Cases per 1M Population | RealClearPolitics:

Death projections

On March 31, 2020, the CDC projected that, even under the best case scenario, eventually at least 100,000 Americans would die of coronavirus.[405] This death toll was reached within two months after the CDC made its projection.[406] Then, at the end of May, the CDC projected the death toll would reach 115,000–135,000 by June 20.[407] The CDC eventually counted 119,000 deaths by this date.[408]

The University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) on July 30 predicted 230,000 deaths by November 1 under current conditions.[409] The CDC ensemble forecast as of July 31 predicts between 168,000 and 182,000 total COVID-19 deaths by August 22.[410]

For comparison, the CDC estimated deaths in the U.S. from the 1918 Spanish Flu, the 1957–1958 influenza pandemic, and the 1968 Hong Kong flu were 675,000, 116,000 and 100,000 respectively.[411] Adjusted for growth in population, these would be per-capita equivalents of 2,147,000, 218,000, and 164,000, respectively, in 2020.

Impact of face coverings

IHME predicted that universal wearing of face masks could prevent between 17,000 and 28,000 deaths between June 26 and October 1, 2020.[412] An IHME model in late July 2020 projected that nationwide deaths would exceed 250,000 by November 1 if people did not wear masks but could be reduced to 198,000 with universal mask-wearing.[409]

See also

- COVID-19 pandemic by country and territory

- Misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic

- United States House Select Committee on the Coronavirus Crisis

- United States influenza statistics by flu season

- COVID Tracking Project

- COVID-19 pandemic in North America

Notes

- A lack of mass testing obscured the extent of the outbreak.[18]

- If the microstates of Andorra and San Marino are excluded, the U.S. has the eighth-highest death rate globally.

- This chart only includes lab-confirmed cases and deaths. Not all states report recoveries. Data for the current day may be incomplete.

- The editorial board for The Wall Street Journal suggested the world may have been "better prepared" had the WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 23, by which time the virus had spread to other countries.[107]

References

- Sheikh, Knvul; Rabin, Roni Caryn (March 10, 2020). "The Coronavirus: What Scientists Have Learned So Far". The New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- "Coronavirus: the first three months as it happened". Nature. April 22, 2020. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00154-w. PMID 32152592. S2CID 212652777.

- Holshue, Michelle L.; DeBolt, Chas; Lindquist, Scott; Lofy, Kathy H.; Wiesman, John; Bruce, Hollianne; Spitters, Christopher; Ericson, Keith; Wilkerson, Sara; Tural, Ahmet; Diaz, George; Cohn, Amanda; Fox, LeAnne; Patel, Anita; Gerber, Susan I.; Kim, Lindsay; Tong, Suxiang; Lu, Xiaoyan; Lindstrom, Steve; Pallansch, Mark A.; Weldon, William C.; Biggs, Holly M.; Uyeki, Timothy M.; Pillai, Satish K. (March 5, 2020). "First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States". New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (10): 929–936. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. PMC 7092802. PMID 32004427.

- "Second Travel-related Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Detected in United States". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Second Travel-related Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Detected in United States: The patient returned to the U.S. from Wuhan on January 13, 2020

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Cases in U.S." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data lags one day behind other sources.

- "Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV)" (ArcGIS). Johns Hopkins CSSE. Frequently updated.

- "Our Data". The COVID Tracking Project. Frequently updated.

- Ghinai, Isaac; McPherson, Tristan D; Hunter, Jennifer C; Kirking, Hannah L; Christiansen, Demian; Joshi, Kiran; Rubin, Rachel; Morales-Estrada, Shirley; Black, Stephanie R; Pacilli, Massimo; Fricchione, Marielle J; Chugh, Rashmi K; Walblay, Kelly A; Ahmed, N Seema; Stoecker, William C; Hasan, Nausheen F; Burdsall, Deborah P; Reese, Heather E; Wallace, Megan; Wang, Chen; Moeller, Darcie; Korpics, Jacqueline; Novosad, Shannon A; Benowitz, Isaac; Jacobs, Max W; Dasari, Vishal S; Patel, Megan T; Kauerauf, Judy; Charles, E Matt; Ezike, Ngozi O; Chu, Victoria; Midgley, Claire M; Rolfes, Melissa A; Gerber, Susan I; Lu, Xiaoyan; Lindstrom, Stephen; Verani, Jennifer R; Layden, Jennifer E (2020). "First known person-to-person transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the USA". Lancet. 395 (10230): 1137–1144. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30607-3. PMC 7158585. PMID 32178768.

- Moon, Sarah (April 24, 2020). "A seemingly healthy woman's sudden death is now the first known US coronavirus-related fatality". CNN. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- "CDC Weekly Key Messages: March 29, 2020 as of 10:30 p.m." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 29, 2020. Archived from the original on April 28, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Smith, Oliver (April 21, 2020). "The only places on Earth still (apparently) without coronavirus". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 24, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Farber, Madeline (January 28, 2020). "China spurned CDC offer to send a team to help contain coronavirus: US Health Secretary". Fox News.

- Aubrey, Allison (January 31, 2020). "Trump Declares Coronavirus A Public Health Emergency And Restricts Travel From China". NPR. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

'Foreign nationals other than immediate family of U.S. citizens and permanent residents who have traveled in China in the last 14 days will be denied entry into United States,' Azar said.

- Robertson, Lori (April 15, 2020). "Trump's Snowballing China Travel Claim". FactCheck.org. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

... effective February 2.

- Lemire, Jonathan; Miller, Zeke; Colvin, Jill; Alonso-Zaldivar, Ricardo (April 12, 2020). "Signs missed and steps slowed in Trump's pandemic response". Associated Press. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Pilkington, Ed; McCarthy, Tom (March 28, 2020). "The missing six weeks: how Trump failed the biggest test of his life". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- Ollstein, Alice Miranda (April 14, 2020). "Trump halts funding to World Health Organization". Politico. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Whoriskey, Peter; Satija, Neena (March 16, 2020). "How U.S. coronavirus testing stalled: Flawed tests, red tape and resistance to using the millions of tests produced by the WHO". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- Blake, Aaron (June 24, 2020). "A timeline of Trump playing down the coronavirus threat". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- Liptak, Kevin (March 13, 2020). "Trump declares national emergency—and denies responsibility for coronavirus testing failures". CNN. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Wang, Jessica; Huth, Lindsay; Umlauf, Taylor; Wang, Elbert; McKay, Betsy (March 22, 2020). "How the CDC's Restrictive Testing Guidelines Hid the Coronavirus Epidemic". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Biesecker, Michael (April 7, 2020). "US 'wasted' months before preparing for coronavirus pandemic". Associated Press. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Watson, Kathryn (March 27, 2020). "Trump invokes Defense Production Act to require GM to produce ventilators". CBS News. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Robertson, Lori (April 7, 2020). "The HHS Inspector General Report". Factcheck.org. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Good, Dan (April 11, 2020). "Every U.S. state is now under disaster declaration". NBC News. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Gearan, Anne; DeBonis, Mike; Dennis, Brady (May 9, 2020). "Trump plays down coronavirus testing as U.S. falls far short of level scientists say is needed". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Deb, Sopan; Cacciola, Scott; Stein, Marc (March 11, 2020). "Sports Leagues Bar Fans and Cancel Games Amid Coronavirus Outbreak". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Godoy, Maria (May 30, 2020). "What Do Coronavirus Racial Disparities Look Like State By State?". NPR.

- Karson, Kendall; Scanlan, Quinn (May 22, 2020). "Black Americans and Latinos nearly 3 times as likely to know someone who died of COVID-19: POLL". ABC News.

- "States tracking COVID-19 race and ethnicity data". American Medical Association. July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- Tavernise, Sabrina; Oppel Jr, Richard A. (March 23, 2020). "Spit On, Yelled At, Attacked: Chinese-Americans Fear for Their Safety". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- "COVID-19 Infections And Deaths Are Higher Among Those With Intellectual Disabilities". NPR.org.

- "U.S. Navy Policies Battling COVID-19 Rely Heavily On Isolation". NPR.org.

- Paige Winfield Cunningham; Paulina Firozi. "The Health 202: The Trump administration is eyeing a new testing strategy for coronavirus, Anthony Fauci says". The Washington Post.

- "How Does Testing in the U.S. Compare to Other Countries?". Johns Hopkins Univ. of Medicine. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- "coronavirus data JHU".

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) deaths worldwide per one million population as of August 11, 2020, by country". Statista. August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "Mortality Analyses—Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center". Johns Hopkins University. n.d. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "Alabama's COVID-19 Data and Surveillance Dashboard". Alabama Department of Public Health. August 16, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- "COVID-19: Case Counts". Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "ADHS - Data Dashboard". Arizona Department of Health Services. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "COVID-19 Arkansas Department of Health". August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "COVID-19". California Department of Public Health. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Case data | Colorado COVID-19 Updates". August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". State of Connecticut. August 14, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)". Delaware Division of Public Health. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Coronavirus Data". coronavirus.dc.gov. August 14, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Florida's COVID-19 Data and Surveillance Dashboard". Florida Department of Health, Division of Disease Control and Health Protection. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Georgia Department of Public Health COVID-19 Daily Status Report". Georgia Department of Public Health. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "COVID-19". dphss.guam.gov. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Current Situation in Hawaii". health.hawaii.gov. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Idaho Official Resources for the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19)". Idaho Official Government Website. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "COVID-19 in Idaho". public.tableau.com. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), Illinois Test Results". Illinois Department of Public Health. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "ISDH - Novel Coronavirus: Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19)". coronavirus.in.gov. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "COVID-19 Dashboard". Regenstrief Institute. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "COVID-19 in Iowa". coronavirus.iowa.gov. August 13, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "COVID-19 Cases in Kansas | KDHE COVID-19". coronavirus.kdheks.gov. August 14, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "kycovid19.ky.gov". govstatus.egov.com. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "COVID-19 Daily Report" (PDF). chfs.ky.gov. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) | Department of Health | State of Louisiana". ldh.la.gov. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19)". Maine Center for Disease Control & Prevention: Division of Disease Surveillance. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Coronavirus - Maryland Department of Health". coronavirus.maryland.gov. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "COVID-19 Daily Dashboard". mass.gov. Commonwealth of Massachusets. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "COVID-19 Weekly Public Health Report". mass.gov. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Coronavirus - Michigan Data". State of Michigan. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Situation Update for COVID-19". Minnesota Department of Health. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Mississippi State Department of Health. August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.