51st state

"51st state", in post-1959 American political discourse, is a phrase that refers to areas or locales that are—seriously or facetiously—considered candidates for U.S. statehood, joining the 50 states that presently compose the United States. The phrase has been applied to external territories as well as parts of existing states which would be admitted as separate states in their own right.

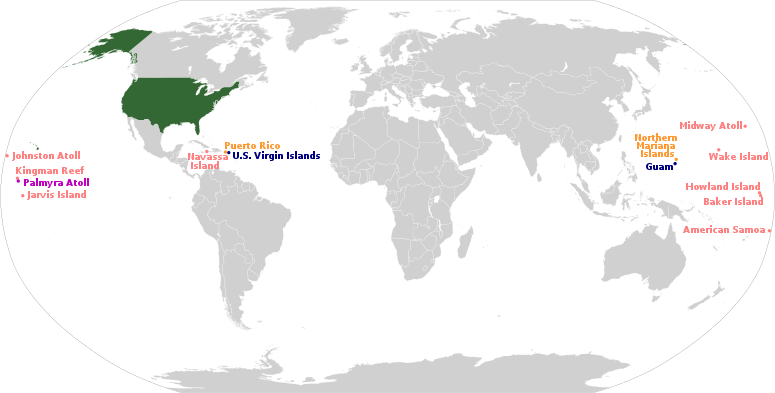

Voters in the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have both voted for statehood in referendums.[1][2] As statehood candidates, their admission to the Union requires congressional approval.[3] American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the United States Virgin Islands are also U.S. territories and could potentially become U.S. states.[4]

The phrase "51st state" sometimes has international political connotations not necessarily having to do with becoming a U.S. state. The phrase "51st state" can be used in a positive sense, meaning that a region or territory is so aligned, supportive, and conducive with the United States, that it is like a U.S. state. It can also be used in a pejorative sense, meaning an area or region is perceived to be under excessive American cultural or military influence or control. In various countries around the world, people who believe their local or national culture has become too Americanized sometimes use the term "51st state" in reference to their own countries.[5]

Before Alaska and Hawaii became states of the United States in 1959, the corresponding expression was "the 49th state".

Legal requirements

Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1 of the United States Constitution authorizes Congress to admit new states into the United States (beyond the thirteen already in existence at the time the Constitution went into effect in 1788). Historically, most new states brought into being by Congress have been established from an organized incorporated territory, created and governed by Congress.[6] In some cases, an entire territory became a state; in others some part of a territory became a state. As defined in a 1953 U.S. Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, the traditionally accepted requirements for statehood are:

- The inhabitants of the proposed new state are imbued with and are sympathetic toward the principles of democracy as exemplified in the American Constitution.

- A majority of the electorate wish statehood.

- The proposed new state has sufficient population and resources to support state government and...carry its share of the cost of Federal Government.[7]

In most cases, the organized government of a territory made known the sentiment of its population in favor of statehood, usually by referendum. Congress then directed that government to organize a constitutional convention to write a state constitution. Upon acceptance of that constitution by the people of the territory and then by Congress, a joint resolution would be adopted granting statehood. The President would then issue a proclamation announcing the addition of a new state to the Union. While Congress, which has ultimate authority over the admission of new states, has usually followed this procedure, there have been occasions (due to unique case-specific circumstances) where it did not.[8]

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico has been discussed as a potential 51st state of the United States. However, since 1898, five other territories were annexed in the time Puerto Rico has been a colonial possession. In 2019, H.R.1965 – Puerto Rico Admission Act, only 5% of the lower legislature were in support. The bill was passed on to the House Committee on Natural Resources.[9]

In a 2012 status referendum a majority of voters, 54%, expressed dissatisfaction with the current political relationship. In a separate question, 61% of voters supported statehood (excluding the 26% of voters who left this question blank). On December 11, 2012, Puerto Rico's legislature resolved to request that the President and the U.S. Congress act on the results, end the current form of territorial status and begin the process of admitting Puerto Rico to the Union as a state.[10] On January 4, 2017, Puerto Rico's new representative to Congress pushed a bill that would ratify statehood by 2025.[11]

On June 11, 2017, another non-binding referendum was held where 97.7 percent voted for the statehood option. The turnout for this vote was only 23 percent. Some leaders of the New Progressive Party say this was because of migration of Puerto Ricans to the mainland. This referendum was boycotted by the two parties opposed to statehood.

On June 27, 2018, the Puerto Rico Admission Act of 2018 H.R. 6246 was introduced in the U.S. House with the purpose of responding to, and complying with, the democratic will of the United States citizens residing in Puerto Rico as expressed in the plebiscites held on November 6, 2012, and June 11, 2017, by setting forth the terms for the admission of the territory of Puerto Rico as a State of the Union.[12] The admission act has 37 original cosponsors between Republicans and Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives.[13]

On May 16, 2020, Puerto Rican Governor Wanda Vázquez announced that Puerto Rico will hold a nonbinding referendum on November 3, 2020 to decide whether Puerto Rico should become a state. For the first time in the island's history, the referendum will ask a single, simple question: Should Puerto Rico be immediately admitted as a U.S. state?

Background

Since 1898, Puerto Rico has had limited representation in the United States Congress in the form of a Resident Commissioner, a nonvoting delegate. The 110th Congress returned the Commissioner's power to vote in the Committee of the Whole, but not on matters where the vote would represent a decisive participation.[14] Puerto Rico has elections on the United States presidential primary or caucus of the Democratic Party and the Republican Party to select delegates to the respective parties' national conventions although presidential electors are not granted on the Electoral College. As American citizens, Puerto Ricans can vote in U.S. presidential elections, provided they reside in one of the 50 states or the District of Columbia and not in Puerto Rico itself.

Residents of Puerto Rico pay U.S. federal taxes: import and export taxes, federal commodity taxes, social security taxes, thereby contributing to the American Government. Most Puerto Rico residents do not pay federal income tax but do pay federal payroll taxes (Social Security and Medicare). However, federal employees, those who do business with the federal government, Puerto Rico–based corporations that intend to send funds to the U.S. and others do pay federal income taxes. Puerto Ricans may enlist in the U.S. military. Puerto Ricans have participated in all American wars since 1898; 52 Puerto Ricans had been killed in the Iraq War and War in Afghanistan by November 2012.[15]

Puerto Rico has been under U.S. sovereignty for over a century after it was ceded to the U.S. by Spain following the end of the Spanish–American War, and Puerto Ricans have been U.S. citizens since 1917. The island's ultimate status has not been determined, and its residents do not have voting representation in their federal government. Like the states, Puerto Rico has self-rule, a republican form of government organized pursuant to a constitution adopted by its people, and a bill of rights.

This constitution was created when the U.S. Congress directed local government to organize a constitutional convention to write the Puerto Rico Constitution in 1951. The acceptance of that constitution by Puerto Rico's electorate, the U.S. Congress, and the U.S. president occurred in 1952. In addition, the rights, privileges and immunities attendant to United States citizens are "respected in Puerto Rico to the same extent as though Puerto Rico were a State of the Union" through the express extension of the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the U.S. Constitution by the U.S. Congress in 1948.[16]

Puerto Rico is designated in its constitution as the "Commonwealth of Puerto Rico".[17] The Constitution of Puerto Rico, which became effective in 1952, adopted the name of Estado Libre Asociado (literally translated as "Free Associated State"), officially translated into English as Commonwealth, for its body politic.[18][19] The island is under the jurisdiction of the Territorial Clause of the U.S. Constitution, which has led to doubts about the finality of the Commonwealth status for Puerto Rico. In addition, all people born in Puerto Rico become citizens of the U.S. at birth (under provisions of the Jones–Shafroth Act in 1917), but citizens residing in Puerto Rico cannot vote for the President of the United States nor for full members of either house of Congress. Statehood would grant island residents full voting rights at the federal level. The Puerto Rico Democracy Act (H.R. 2499) was approved on April 29, 2010, by the United States House of Representatives (223–169),[20] but was not approved by the Senate before the end of the 111th Congress. It would have provided for a federally sanctioned self-determination process for the people of Puerto Rico. This act would provide for referendums to be held in Puerto Rico to determine the island's ultimate political status. It had also been introduced in 2007.[21]

Vote for statehood

| Puerto Rican status referendum, 2012 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Location | Puerto Rico | |

| Date | November 6, 2012 | |

| Voting system | simple majority for the first question first-past-the-post for the second question | |

| Should Puerto Rico continue its current territorial status? | ||

| Which non-territorial option do you prefer? | ||

In November 2012, a referendum resulted in 54 percent of respondents voting to reject the current status under the territorial clause of the U.S. Constitution,[23] while a second question resulted in 61 percent of voters identifying statehood as the preferred alternative to the current territorial status.[24] The 2012 referendum was by far the most successful referendum for statehood advocates and support for statehood has risen in each successive popular referendum.[25][26] However, more than one in four voters abstained from answering the question on the preferred alternative status. Statehood opponents have argued that the statehood option garnered only 45 percent of the votes if abstentions are included.[27] If abstentions are considered, the result of the referendum is much closer to 44 percent for statehood, a number that falls under the 50 percent majority mark.[28]

The Washington Post, The New York Times and the Boston Herald have published opinion pieces expressing support for the statehood of Puerto Rico.[29][30][31] On November 8, 2012, Washington, D.C. newspaper The Hill published an article saying that Congress will likely ignore the results of the referendum due to the circumstances behind the votes.[32] U.S. Congressman Luis Gutiérrez and U.S. Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez, both of Puerto Rican ancestry, agreed with The Hill's statements.[33] Shortly after the results were published, Puerto Rico-born U.S. Congressman José Enrique Serrano commented "I was particularly impressed with the outcome of the 'status' referendum in Puerto Rico. A majority of those voting signaled the desire to change the current territorial status. In a second question an even larger majority asked to become a state. This is an earthquake in Puerto Rican politics. It will demand the attention of Congress, and a definitive answer to the Puerto Rican request for change. This is a history-making moment where voters asked to move forward."[34]

Several days after the referendum, the Resident Commissioner Pedro Pierluisi, Governor Luis Fortuño, and Governor-elect Alejandro García Padilla wrote separate letters to the President of the United States, Barack Obama, addressing the results of the voting. Pierluisi urged Obama to begin legislation in favor of the statehood of Puerto Rico, in light of its win in the referendum.[35] Fortuño urged him to move the process forward.[36] García Padilla asked him to reject the results because of their ambiguity.[37] The White House stance related to the November 2012 plebiscite was that the results were clear, the people of Puerto Rico want the issue of status resolved, and a majority chose statehood in the second question. Former White House director of Hispanic media stated, "Now it is time for Congress to act and the administration will work with them on that effort, so that the people of Puerto Rico can determine their own future."[38]

On May 15, 2013, Resident Commissioner Pierluisi introduced H.R. 2000 to Congress to "set forth the process for Puerto Rico to be admitted as a state of the Union", asking for Congress to vote on ratifying Puerto Rico as the 51st state.[39] On February 12, 2014, Senator Martin Heinrich introduced a bill in the U.S. Senate. The bill would require a binding referendum to be held in Puerto Rico asking whether the territory wants to be admitted as a state. In the event of a yes vote, the president would be asked to submit legislation to Congress to admit Puerto Rico as a state.[40]

Government funding for a fifth referendum

On January 15, 2014, the United States House of Representatives approved $2.5 million in funding to hold a referendum. This referendum can be held at any time as there is no deadline by which the funds have to be used.[41] The United States Senate then passed the bill which was signed into law on January 17, 2014, by Barack Obama, then President of the United States.[42]

2017 referendum

| Puerto Rican status referendum, 2017 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Location | Puerto Rico | |

| Date | June 11, 2017 | |

| Voting system | Plurality | |

| Results | ||

The previous plebiscites provided voters with three options: statehood, free association, and independence. The Puerto Rican status referendum of 2017 originally offered only two options: Statehood and Independence/Free Association; however, a "current territorial status" was added before the referendum took place. The referendum was held on June 11, 2017, with an overwhelming majority of voters supporting statehood at 97.16%; however, with a voter turnout of 22.99%, it was a historical low. If the majority voted for Independence/Free Association, a second vote would have been held to determine the preference: full independence as a nation or associated free state status with independence but with a "free and voluntary political association" between Puerto Rico and the United States. The specifics of the association agreement[43] would be detailed in the Compact of Free Association that would be negotiated between the U.S. and Puerto Rico. That document might cover topics such as the role of the U.S. military in Puerto Rico, the use of the U.S. currency, free trade between the two entities, and whether Puerto Ricans would be U.S. citizens.[44]

Former Governor Ricardo Rosselló was strongly in favor of statehood to help develop the economy and help to "solve our 500-year-old colonial dilemma ... Colonialism is not an option .... It's a civil rights issue ... 3.5 million citizens seeking an absolute democracy," he told the news media.[45] Benefits of statehood include an additional $10 billion per year in federal funds, the right to vote in presidential elections, higher Social Security and Medicare benefits, and a right for its government agencies and municipalities to file for bankruptcy. The latter is currently prohibited.[46]

At approximately the same time as the referendum, Puerto Rico's legislators are also expected to vote on a bill that would allow the Governor to draft a state constitution and hold elections to choose senators and representatives to the United States Congress. Regardless of the outcome of the referendum or the bill on drafting a constitution, action by Congress would be necessary to implement changes to the status of Puerto Rico under the Territorial Clause of the United States Constitution.[46]

If the majority of Puerto Ricans were to choose the Free Association option—and only 33% voted for it in 2012—and if it were granted by the U.S. Congress, Puerto Rico would become a Free Associated State, a virtually independent nation. It would have a political and economical treaty of association with the U.S. that would stipulate all delegated agreements. This could give Puerto Rico a similar status to Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau, countries which currently have a Compact of Free Association with the United States.

Those Free Associated States use the American dollar, receive some financial support and the promise of military defense if they refuse military access to any other country. Their citizens are allowed to work in the U.S. and serve in its military.[43]

On June 11, 500,000 Puerto Ricans voted for statehood, 7,600 voted for independence, and 6,700 voted for status quo.[47]

Guam

Guam (formally the Territory of Guam) is an unincorporated and organized territory of the United States. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, Guam is one of five American territories with an established civilian government.[48][49]

In the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a significant movement in favor of this U.S. territory becoming a commonwealth, which would give it a level of self-government similar to Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands. However, the federal government rejected the version of a commonwealth that the government of Guam proposed, because its clauses were incompatible with the Territorial Clause (Art. IV, Sec. 3, cl. 2) of the U.S. Constitution. Other movements advocate U.S. statehood for Guam, union with the state of Hawaii, or union with the Northern Mariana Islands as a single territory, or independence.[50]

In a 1982 plebiscite, voters indicated interest in seeking commonwealth status. The island has been considering another non-binding plebiscite on decolonization since 1998. Governor Eddie Baza Calvo intended to include one during the island's November 2016 elections but it was delayed again.[51]

A Commission on Decolonization was established in 1997 to educate the people of Guam about the various political status options in its relationship with the U.S.: statehood, free association and independence. The group was dormant for some years. In 2013, the commission began seeking funding to start a public education campaign. There were few subsequent developments until late 2016. In early December 2016, the Commission scheduled a series of education sessions in various villages about the current status of Guam's relationship with the U.S. and the self-determination options that might be considered.[51] The commission's current Executive Director is Edward Alvarez and there are ten members. The group is also expected to release position papers on independence and statehood but the contents have not yet been completed.[50]

Guam has been occupied for over 450 years by the Spanish, the Japanese, and the United States. In 2016, Governor Eddie Calvo planned a decolonization referendum that the indigenous Chamorro people of Guam would solely participate in, in which the three options would be given, including statehood, independence, and free association. However, this referendum for the Chamorro people was struck down by a federal judge on the grounds of racial discrimination. In the wake of this ruling, Governor Calvo has suggested that two ballots be held: one for the Chamorro People and one for eligible U.S. citizens who are non-indigenous residents of Guam. A reunification referendum in Guam and its neighbor, the Northern Mariana Islands (a U.S. Commonwealth) has been proposed.[52][53] A 2016 poll conducted by the University of Guam showed a majority supporting statehood when respondents were asked what political status they supported for Guam.[54]

United Nations support

The United Nations is in favor of greater self-determination for Guam and other such territories. The UN's Special Committee on Decolonization has agreed to endorse the Governor's education plan. The commission's May 2016 report states: "With academics from the University of Guam, [the Commission] was working to create and approve educational materials. The Office of the Governor was collaborating closely with the Commission" in developing educational materials for the public.[55]

The United States Department of the Interior had approved a $300,000 grant for decolonization education, Edward Alvarez told the United Nations Pacific Regional Seminar in May 2016. "We are hopeful that this might indicate a shift in [United States] policy to its Non-Self-Governing Territories such as Guam, where they will be more willing to engage in discussions about our future and offer true support to help push us towards true self-governances and self-determination."[56]

Other territories

The U.S. Virgin Islands explored the possibility of statehood in 1984,[57] and most recently in a 1993 referendum, while American Samoa explored the possibility of statehood in 2005[58] and 2017.[59]

District of Columbia

The District of Columbia is often mentioned as a candidate for statehood. In Federalist No. 43 of The Federalist Papers, James Madison considered the implications of the definition of the "seat of government" found in the United States Constitution. Although he noted potential conflicts of interest, and the need for a "municipal legislature for local purposes",[60] Madison did not address the district's role in national voting. Legal scholars disagree on whether a simple act of Congress can admit the District as a state, due to its status as the seat of government of the United States, which Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution requires to be under the exclusive jurisdiction of Congress; depending on the interpretation of this text, admission of the full District as a state may require a Constitutional amendment, which is much more difficult to enact.[61] However, the Constitution does not set a minimum size for the District. Its size has already changed once before, when Virginia reclaimed the portion of the District south of the Potomac. So the constitutional requirement for a federal district can be satisfied by reducing its size to the small central core of government buildings and monuments.

The District of Columbia residents who support the statehood movement sometimes use the slogan "Taxation without representation" to denote their lack of Congressional representation. The phrase is a shortened version of the Revolutionary War protest motto "no taxation without representation" omitting the initial "No", and is now printed on newly issued District of Columbia license plates (although a driver may choose to have the District of Columbia website address instead). President Bill Clinton's presidential limousine had the "Taxation without representation" license plate late in his term, while President George W. Bush had the vehicle's plates changed shortly after beginning his term in office.[62] President Barack Obama had the license plates changed back to the protest style shortly before his second-term inauguration.[63] President Donald Trump eventually removed the license plate and has signaled opposition to DC statehood[64][65]

This position was carried by the D.C. Statehood Party, a political party; it has since merged with the local Green Party affiliate to form the D.C. Statehood Green Party. The nearest this movement ever came to success was in 1978, when Congress passed the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment. Two years later in 1980, local citizens passed an initiative calling for a constitutional convention for a new state. In 1982, voters ratified the constitution of the state, which was to be called New Columbia. The drive for statehood stalled in 1985, however, when the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment failed because not enough states ratified the amendment within the seven-year span specified.

Another proposed option would be to have Maryland, from which the current land was ceded, retake the District of Columbia, as Virginia has already done for its part, while leaving the National Mall, the United States Capitol, and the White House in a truncated District of Columbia.[66] This would give residents of the District of Columbia the benefit of statehood while precluding the creation of a 51st state, but would require the consent of the Government of Maryland.[67]

2016 statehood referendum

| District of Columbia statehood referendum, 2016 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Location | District of Columbia | |

| Date | November 8, 2016 | |

| Voting system | simple majority | |

| Shall the voters of the District of Columbia advise the Council to approve or reject this proposal? | ||

On April 15, 2016, District Mayor Muriel Bowser called for a citywide vote on whether the nation's capital should become the 51st state.[68] This was followed by the release of a proposed State Constitution.[69] This Constitution would make the Mayor of the District of Columbia the Governor of the proposed state, while the members of the District Council would make up the proposed House of Delegates.[70]

On November 8, 2016, the voters of the District of Columbia voted overwhelmingly in favor of statehood, with 86% of voters voting to advise approving the proposal.[71]

While the name "New Columbia" has long been associated with the movement, the City Council and community members chose the proposed state name to be the State of Washington, D.C., or the State of Washington, Douglass Commonwealth. The abolitionist Frederick Douglass was a D.C. resident and was chosen to be the proposed state's namesake.[72]

Federal enclave

To fulfill Constitutional requirements of having a Federal District and to provide the benefits of statehood to the 700,000-plus residents of D.C., in the proposed State of Washington, D.C., boundaries would be delineated between the State of Washington, D.C. and a much smaller federal seat of government. This would ensure federal control of federal buildings. The National Mall, the White House, the national memorials, Cabinet buildings, judicial buildings, legislative buildings, and other government-related buildings, etc. would be housed within the much smaller federal seat of government. All residences in the State of Washington, D.C. would reside outside the seat of federal government, except for the White House. The proposed boundaries are based on precedents created through the 1902 McMillan Plan with a few modifications. The rest of the boundaries would remain the same. A map of DC in the event of statehood with the federal enclave can be seen here[73][74][75]

Admission legislation

On June 26, 2020 the United States House of Representatives voted 232–180 in favor of statehood for Washington, D.C. Passage of this legislation in the Senate is not expected while the Republican Party has a Senate majority. President Trump has also promised to veto D.C. statehood.[76] The legislation was House Resolution 51[77] in honor of DC potentially becoming the 51st state.[78] The vote was the first time D.C. has ever had a vote for statehood pass any chamber of Congress. In 1993, D.C. statehood legislation was rejected in a US House floor vote 153–277.[79]

US flag

If a new U.S. state were to be admitted, it would require a new design of the flag to accommodate an additional star for a 51st state.[80] However, according to the U.S. Army Institute of Heraldry, the United States flag never becomes obsolete. In the event that a new state is added to the Union and a 51-star flag is approved, any approved American flag (such as the 50-star flag) may continue to be used and displayed until no longer serviceable.[81]

By status changes of former U.S. territories

Philippines

The Philippines has had small grassroots movements for U.S. statehood.[82] Originally part of the platform of the Progressive Party, then known as the Federalista Party, the party dropped it in 1907, which coincided with the name change.[83][84] In 1981, the presidential candidate for the Federal Party ran on a platform of Philippine Statehood.[85] As recently as 2004, the concept of the Philippines becoming a U.S. state has been part of a political platform in the Philippines.[86] Supporters of this movement include Filipinos who believe that the quality of life in the Philippines would be higher and that there would be less poverty there if the Philippines were an American state or territory. Supporters also include Filipinos that had fought as members of the United States Armed Forces in various wars during the Commonwealth period.[87][88][89]

The Philippine statehood movement had a significant impact during the early American colonial period.[84] It is no longer a mainstream movement,[90] but is a small social movement that gains interest and talk in that nation.[91]

By partition of or secession from current U.S. states

There exist several proposals to divide states with regions that are politically or culturally divergent into smaller, more homogeneous, administratively efficient entities.[92] Splitting a state requires the approval of both its legislature and the U.S. Congress.[93]

Proposals of new states by partition include:

- Arizona: The secession of Pima County in Arizona, with the hopes of neighboring counties Cochise, Yuma, and Santa Cruz joining to form a state.[94]

- California and Oregon:

- The secession of Northern California and Southern Oregon to form a state named Jefferson.

- Various proposals of partition and secession in California, usually splitting the south half from the north or the urban coastline from the rest of the state.[95] In 2014, businessman Tim Draper collected signatures for a petition to split California into six different states,[96] but not enough to qualify for the ballot.[97] Tim Draper attempted a follow-up petition to split California into three states in 2018.[98][99] However, the initiative to divide California into three states was ordered removed from the 2018 ballot by the California Supreme Court, as the California constitution does not allow this type of action to be undertaken as a ballot initiative.[100][101][102]

- Colorado: In 2013, commissioners in Weld County, Colorado, announced a proposal to leave Colorado along with neighboring counties of Morgan, Logan, Sedgwick, Phillips, Washington, Yuma, and Kit Carson to form the state of North Colorado.[103] The counties in contention voted to begin plans for secession that November, with mixed results.[104]

- Delaware, Maryland and Virginia: The secession of several counties from the eastern shores of Maryland and Virginia, combining with some or all of the state of Delaware, forming a state named Delmarva.[105]

- Florida: The secession of South Florida and the Greater Miami area to form a state named South Florida. The region has a population of over 7 million, comprising 41% of Florida's population.[106]

- Illinois:

- The secession of Cook County, which contains Chicago, from Illinois to form a separate state, proposed by residents of the more Republican Downstate Illinois to free it from the political influence of the heavily Democratic Chicago area.[107]

- The secession of Southern Illinois from the rest of the state, south of Springfield, with the capital in Mt. Vernon.

- Maryland: The secession of five counties on the western side of the state due to political differences with the more liberal central part of the state.[108]

- Michigan: The secession of the geographically separate and culturally distinct Upper Peninsula of Michigan from the Lower Peninsula, as a state called Superior.

- New York: Various proposals partitioning New York into separate states, all of which involve to some degree the separation of New York City from the rest of the state.[109]

- Texas: Under the resolution by which the Republic of Texas was admitted to the Union and the state constitution, it has the right to divide itself into up to five states. There were a significant number of Texans who supported dividing the state in its early decades, called divisionists.[110][111][112] Current Texas politics and self-image make any tampering with Texas' status as the largest state by land area in the contiguous United States unlikely.[113][114][115]

- Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona: Admitting into the Union the Navajo Nation, the largest Indian Reservation in the United States. Reservations already enjoy a large degree of political autonomy, so making a state out of the Navajo Nation would not be as problematic as partitioning areas of other states.[116] The Navajo Nation is currently larger than ten U.S. States.[117] A Navajo state would also help issues of representation, since as of 2020, only four Representatives and no Senators were Native American.

- Washington: Dividing the state into Western Washington and Eastern Washington via the Cascade Mountains. Suggested names include East Washington, Lincoln, Cascadia, and more recently, Liberty.

- The National Movement for the Establishment of a 49th State, founded by Oscar Brown Sr. and Bradley Cyrus, and active in Chicago between 1934 and 1937, had the aim of forming an African-American state in the South.[118][119]

Use internationally

Some countries, because of their cultural similarities and close alliances with the United States, are often described as a 51st state. In other countries around the world, movements with various degrees of support and seriousness have proposed U.S. statehood.

North America

Canada

In Canada, "the 51st state" is a phrase generally used in such a way as to imply that if a certain political course is taken, Canada's destiny will be as little more than a part of the United States. Examples include the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement in 1988, the debate over the creation of a common defense perimeter, and as a potential consequence of not adopting proposals intended to resolve the issue of Quebec sovereignty, the Charlottetown Accord in 1992 and the Clarity Act in 1999.

The phrase is usually used in local political debates, in polemic writing or in private conversations. It is rarely used by politicians themselves in a public context, although at certain times in Canadian history political parties have used other similarly loaded imagery. In the 1988 federal election, the Liberals asserted that the proposed Free Trade Agreement amounted to an American takeover of Canada[120]—notably, the party ran an ad in which Progressive Conservative (PC) strategists, upon the adoption of the agreement, slowly erased the Canada-U.S. border from a desktop map of North America.[121] Within days, however, the PCs responded with an ad which featured the border being drawn back on with a permanent marker, as an announcer intoned "Here's where we draw the line."[122]

The implication has historical basis and dates to the breakup of British America during the American Revolution. The colonies that had confederated to form the United States invaded Canada (at the time a term referring specifically to the modern-day provinces of Québec and Ontario, which had only been in British hands since 1763) at least twice, neither time succeeding in taking control of the territory. The first invasion was during the Revolution, under the assumption that French-speaking Canadians' presumed hostility towards British colonial rule combined with the Franco-American alliance would make them natural allies to the American cause; the Continental Army successfully recruited two Canadian regiments for the invasion. That invasion's failure forced the members of those regiments into exile, and they settled mostly in upstate New York. The Articles of Confederation, written during the Revolution, included a provision for Canada to join the United States, should they ever decide to do so, without needing to seek U.S. permission as other states would.[123] The United States again invaded Canada during the War of 1812, but this effort was made more difficult due to the large number of Loyalist Americans that had fled to what is now Ontario and still resisted joining the republic. The Hunter Patriots in the 1830s and the Fenian raids after the American Civil War were private attacks on Canada from the U.S.[124] Several U.S. politicians in the 19th century also spoke in favor of annexing Canada,[125] as did Canadian politician William Lyon Mackenzie, who set up a rogue Republic of Canada on a small island near the U.S. border during the Upper Canada Rebellion.

In the United States, the term "the 51st state" when applied to Canada can serve to highlight the similarities and close relationship between the United States and Canada. Sometimes the term is used disparagingly, intended to deride Canada as an unimportant neighbor. In the 1989 Quebec general election, the political party Parti 51 ran 11 candidates on a platform of Quebec seceding from Canada to join the United States (with its leader, André Perron, claiming Quebec could not survive as an independent nation).[126] The party attracted just 3,846 votes across the province, 0.11% of the total votes cast.[127] In comparison, the other parties in favor of sovereignty of Quebec in that election got 40.16% (PQ) and 1.22% (NPDQ).

Alberta

American geopolitics expert Peter Zeihan argued in his book The Accidental Superpower the Canadian province of Alberta would benefit from joining the United States as the 51st state.[128] There is growing support for Alberta separatism resulting from federal government policies which are believed to be harming the province's ability to build pipelines for the province's oil and gas industry and federal equalization payments.[129] In a September 2018 poll, 25% of Albertans believed they would be better off separating from Canada and 62% believed they are not getting enough from confederation.[130]

Newfoundland

In the late 1940s, during the last days of the Dominion of Newfoundland (at the time a dominion-dependency in the Commonwealth and independent of Canada), there was mainstream support, although not majority, for Newfoundland to form an economic union with the United States, thanks to the efforts of the Economic Union Party and significant U.S. investment in Newfoundland stemming from the U.S.-British alliance in World War II. The movement ultimately failed when, in a 1948 referendum, voters narrowly chose to confederate with Canada (the Economic Union Party supported an independent "responsible government" that they would then push toward their goals).[131]

Mexico

In 1847–48, with the United States occupying Mexico at the conclusion of the Mexican–American War, there was talk in Congress of annexing the entirety of Mexico. The result was the Mexican Cession, also called the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo for the town in which the treaty was signed, in which the U.S. annexed over 40% of Mexico. Talk of annexing all of Mexico disappeared after this time. In 1848 a bill was debated in congress that would have annexed the Republic of Yucatán, but a vote failed to take place.[132]

Central America

Due to geographical proximity of the Central American countries to the U.S. which has powerful military, economic, and political influences, there were several movements and proposals by the United States during the 19th and 20th centuries to annex some or all of the Central American republics (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras with the formerly British-ruled Bay Islands, Nicaragua, Panama which had the U.S.-ruled Canal Zone territory from 1903 to 1979, and Belize, which is a constitutional monarchy and was known as British Honduras until 1981). However, the U.S. never acted on these proposals from some U.S. politicians; some of which were never delivered or considered seriously. In 2001, El Salvador adopted the U.S. dollar as its currency, while Panama has used it for decades due to its ties to the Canal Zone.

Cuba

In 1854 the Ostend Manifesto was written, outlining the rationale for the U.S. to purchase Cuba from Spain, implying taking the island by force if Spain refused. Once the document became published, many northern states denounced the document.

In 1859, Senator John Slidell introduced a bill to purchase Cuba from Spain.[133][134]

Cuba, like many Spanish territories, wanted to break free from Spain. A pro-independence movement in Cuba was supported by the U.S., and Cuban guerrilla leaders wanted annexation to the United States, but Cuban revolutionary leader José Martí called for Cuban nationhood. When the U.S. battleship Maine sank in Havana Harbor, the U.S. blamed Spain and the Spanish–American War broke out in 1898. After the U.S. won, Spain relinquished claim of sovereignty over territories, including Cuba. The U.S. administered Cuba as a protectorate until 1902. Several decades later in 1959, the Cuban government of U.S.-backed Fulgencio Batista was overthrown by Fidel Castro who subsequently installed a Marxist–Leninist government. When the U.S. refused to trade with Cuba, Cuba allied with the Soviet Union who imported Cuban sugar, Cuba's main export. The government installed by Fidel Castro has been in power ever since. In 2016, the U.S. eased trade and travel restrictions against Cuba.[135] United Airlines submitted a formal application to the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) for authority to provide service from four of its largest U.S. gateway cities—Newark/New York, Houston, Washington, D.C. and Chicago—to Havana's José Martí International Airport.[136]

Dominica

In 1898, one or more news outlets in the Caribbean noted growing sentiments of resentment of British rule in Dominica, including the system of administration over the country. These publications attempted to gauge sentiments of annexation to the United States as a way to change this system of administration.[137]

Dominican Republic

On June 30, 1870, the United States Senate took a vote on an annexation treaty with the Dominican Republic, but it failed to proceed.[138]

Greenland

During World War II, when Denmark was occupied by Nazi Germany, the United States briefly controlled Greenland for battlefields and protection. In 1946, the United States offered to buy Greenland from Denmark for $100 million ($1.2 billion today) but Denmark refused to sell it.[139][140] Several politicians, including U.S. president Donald Trump, and others have in recent years argued that Greenland could hypothetically be in a better financial situation as a part of the United States; for instance mentioned by professor Gudmundur Alfredsson at University of Akureyri in 2014.[141][142] One of the actual reasons behind U.S. interest in Greenland could be the vast natural resources of the island.[143] According to WikiLeaks, the U.S. appears to be highly interested in investing in the resource base of the island and in tapping the vast expected hydrocarbons off the Greenlandic coast.[144]

Haiti

Time columnist Mark Thompson suggested that Haiti had effectively become the 51st state after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, with the widespread destruction prompting a quick and extensive response from the United States, even so far as the stationing of the U.S. military in Haitian air and sea ports to facilitate foreign aid.[145]

Asia

Hong Kong

The idea of admission to the United States was discussed among some netizens based on Hong Kong's mature common law system, long tradition of liberalism and vibrant civil society making it a global financial hub very much similar to London or New York.[146][147][148][149][150] alongside proposals of becoming independent (within or outside the Commonwealth, as a republic or a Commonwealth realm),[151] rejoining the Commonwealth,[152] confederation with Canada as the eleventh province or the fourth territory (with reference to Ken McGoogan's proposal regarding Scotland),[153] returning to British rule as a dependent territory,[154] joining the Republic of China (Taiwan),[155] or acceding to other federations as a number of city-states.

Since the 2019–20 Hong Kong protests, discussions on the topic seem to have increased again. However, after the Chinese regime's unilateral enactment of a catered national security law for Hong Kong, such discussions have become "illegal" on suspicion of "secession".

Iraq

Several publications suggested that the Iraq War was a neocolonialist war to make the Republic of Iraq into the 51st U.S. state, though such statements are usually made in a facetious manner, as a tongue-in-cheek statement.[156][157][158][159][160]

Israel and Palestine

Several websites assert that Israel is the 51st state due to the annual funding and defense support it receives from the United States. An example of this concept can be found in 2003 when Martine Rothblatt published a book called Two Stars for Peace that argued for the addition of Israel and the Palestinian territories as the 51st and 52nd states in the Union. The American State of Canaan, is a book published by Prof. Alfred de Grazia, political science and sociologist, in March 2009, proposing the creation of the 51st and 52nd states from Israel and the Palestinian territories.

Japan

In Article 3 of the Treaty of San Francisco between the Allied Powers and Japan, which came into force in April 1952, the U.S. put the outlying islands of the Ryukyus, including the island of Okinawa—home to over 1 million Okinawans related to the Japanese—and the Bonin Islands, the Volcano Islands, and Iwo Jima into U.S. trusteeship.[161] All these trusteeships were slowly returned to Japanese rule. Okinawa was returned on May 15, 1972, but the U.S. stations troops in the island's bases as a defense for Japan.

Taiwan

A poll in 2003 among Taiwanese residents aged between 13 and 22 found that, when given the options of either becoming a province of the People's Republic of China or a state within the U.S., 55% of the respondents preferred statehood while only 36% chose joining China.[162] A group called Taiwan Civil Government, established in Taipei in 2008, claims that the island of Taiwan and other minor islands are the territory of the United States.[163]

Europe

Albania

Albania has often been called the 51st state for its perceived strongly pro-American positions, mainly because of the United States' policies towards it.[164] In reference to President George W. Bush's 2007 European tour, Edi Rama, Tirana's mayor and leader of the opposition Socialists, said: "Albania is for sure the most pro-American country in Europe, maybe even in the world ... Nowhere else can you find such respect and hospitality for the President of the United States. Even in Michigan, he wouldn't be as welcome." At the time of ex-Secretary of State James Baker's visit in 1992, there was even a move to hold a referendum declaring the country as the 51st American state.[165][166] In addition to Albania, Kosovo (which is predominately Albanian) is seen as a 51st state due to the heavy presence and influence of the United States. The U.S. has had troops and the largest base outside U.S. territory, Camp Bondsteel, in the territory since 1999.

Azores

There was a movement among the Azores archipelago to break away from Portugal and join the United States in the late 19th century through the early 20th century. Feeling that they were being unfairly exploited by the authorities on the mainland, this movement believed the best solution was to have the United States govern them. This movement was fueled by a large number of immigrants to the United States, particularly to the New England states, for labor and educational reasons. Also establishing a close social connection between the Azores and the United States were American whaling companies. New England and New York-based whaling ships frequently used the Azores as an overseas base of operations and employed large number of the local population to man the ships. The movement to have the United States annex the Azores reached its climax during World War I when the United States Navy established a base of operations in the Azores. Sensing that the Americans were doing more to defend the Azores from the Germans than the Portuguese Government was, particularly during the raid of SM U-155 on the Azores in 1917, many local politicians openly demanded a change. American Naval officers and politicians, notably Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt, however, dismissed any idea of the United States taking control.

Denmark

In 1989, the Los Angeles Times proclaimed that Denmark becomes the 51st state every Fourth of July, because Danish citizens in and around Aalborg celebrate the American independence day.[167]

Poland

Poland has historically been staunchly pro-American, dating back to General Tadeusz Kościuszko and Casimir Pulaski's involvement in the American Revolution. This pro-American stance was reinforced following favorable American intervention in World War I (leading to the creation of an independent Poland) and the Cold War (culminating in a Polish state independent of Soviet influence). Poland contributed a large force to the "Coalition of the Willing" in Iraq. A quote referring to Poland as "the 51st state" has been attributed to James Pavitt, then Central Intelligence Agency Deputy Director for Operations, especially in connection to extraordinary rendition.[168]

Sicily (Italy)

The Party of Reconstruction in Sicily, which claimed 40,000 members in 1944, campaigned for Sicily to be admitted as a U.S. state.[169] This party was one of several Sicilian separatist movements active after the downfall of Italian Fascism. Sicilians felt neglected or underrepresented by the Italian government after the annexation of 1861 that ended the rule of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies based in Naples. The large population of Sicilians in America and the American-led Allied invasion of Sicily in July–August 1943 may have contributed to the sentiment.

United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland

The United Kingdom has sometimes been called the 51st state due to the "Special Relationship" between the two countries, particularly since the close cooperation between Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill during World War II, and more recently continued during the premierships of Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair.[170]

In a December 29, 2011 column in The Times, David Aaronovitch said in jest that the UK should consider joining the United States, as the British population cannot accept union with Europe and the UK would inevitably decline on its own. He also made an alternative case that England, Scotland, and Wales should be three separate states, with Northern Ireland joining the Republic of Ireland and becoming an all-Ireland state.[171]

Oceania

Australia

In Australia, the term '51st state' is used as a disparagement of a perceived invasion of American cultural or political influence.[172]

New Zealand

In 2010 there was an attempt to register a 51st State Party with the New Zealand Electoral Commission. The party advocates New Zealand becoming the 51st state of the United States of America. The party's secretary is Paulus Telfer, a former Christchurch mayoral candidate.[173][174] On February 5, 2010, the party applied to register a logo with the Electoral Commission.[173] The logo—a U.S. flag with 51 stars—was rejected by the Electoral Commission on the grounds that it was likely to cause confusion or mislead electors.[175] As of 2014, the party remains unregistered and cannot appear on a ballot.

See also

References

- "DC Voters Elect Gray to Council, Approve Statehood Measure". Archived from the original on November 9, 2016.

- Reuters (June 11, 2017). "Puerto Ricans Vote Overwhelmingly For U.S. Statehood". Archived from the original on June 12, 2017 – via Huff Post.

- "How do new states become part of the U.S.?". December 3, 2012. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017.

- "What Are the US Territories?".

- "Sverige var USAs 51a delstat" "EU kritiserar svensk TV" Archived September 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Journalisten (in Swedish)

- "Property and Territory: Powers of Congress". Mountain View, California: Justia. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- "Statehood Considered by Congress Since 1947." In CQ Almanac 1957, 13th ed., 07-646-07-648. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1958. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- Huddle, F. P. (1946). "Admission of new states". Editorial research reports. CQ Press. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- Soto, Darren (March 28, 2019). "Committees - H.R.1965 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): Puerto Rico Admission Act". www.congress.gov.

- The Senate and the House of Representative of Puerto Rico: Concurrent Resolution. Archived March 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- Gidman, Jenn (January 5, 2017). "Puerto Rico Just Made a Major Push for Statehood, With a Noted ETA". Newser. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- Congress.Gov (July 7, 2018). "To enable the admission of the territory of Puerto Rico into the Union as a State, and for other purposes". www.congress.gov.

- Congress.Gov (July 7, 2018). "Cosponsors: H.R.6246 — 115th Congress (2017-2018)". www.congress.gov.

- Rules of the House of Representatives : One Hundred Tenth Congress (archived from the original Archived March 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine on May 28, 2010).

- ICasualties Archived February 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, accessed Nov. 2012.

- 48 U.S.C. § 737, Privileges and immunities.

- The term Commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has sometimes been synonymous with "republic".

- "Constitucion del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico www.LexJuris.com". www.lexjuris.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2011.

- "Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico". welcome.topuertorico.org. Archived from the original on November 25, 2011.

- Arce, Dwyer (April 30, 2010). "US House approves Puerto Rico status referendum bill". Paper Chase. JURIST. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017.

- Garrett, R. Sam; Keith, Bea (June 7, 2011). "Political Status of Puerto Rico: Options for Congress [Report RL32933]" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 4, 2009.

- "Puerto Rico Election Code for the 21st Century". Article 2.003(54), Act No. 78 of 2011 (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- CONDICIÓN POLÍTICA TERRITORIAL ACTUAL (English:Actual Territorial Political Condition). Archived November 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Government of Puerto Rico. State Electoral Commission. November 16, 2012 9:59PM. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- OPCIONES NO TERRITORIALES. (English: Non-Territorial Options). Archived November 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Government of Puerto Rico. State Electoral Commission. November 16, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- "An Introduction to Puerto Rico's Status Debate". Let Puerto Rico Decide. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- "Puerto Ricans favor statehood for first time". CNN.com. November 7, 2012. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- "Did Puerto Rico Really Vote for Statehood?". Huffington Post. November 14, 2012. Archived from the original on November 17, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

- García Padilla, Alejandro (November 9, 2012). "Alejandro García Padilla letter to Barack Obama". Archived from the original on March 7, 2016.

- "A good deal for the District and Puerto Rico". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 18, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- David Royston Patterson (November 24, 2012). "Will Puerto Rico Be America's 51st State?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- "Puerto Rican statehood". Boston Herald. November 25, 2012. Archived from the original on November 28, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Kasperowicz, Pete (November 8, 2012). "Congress expected to ignore Puerto Rico's vote for statehood". The Hill. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012.

- "El Congreso no hará caso a los resultados del plebiscito". El Nuevo Día. November 9, 2012. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012.

- "Serrano: Plebiscite an 'Earthquake' in Puerto Rican Politics" Archived November 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- Pierluisi, Pedro (November 13, 2012). "Pedro Pierluisi letter to Barack Obama" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 19, 2012.

- "Governor of Puerto Rico Letter to the President – Official Results of the 2012 Puerto Rico Political Status Plebiscite". Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- García Padilla, Alejandro (November 9, 2012). "Alejandro García Padilla letter to Barack Obama". Archived from the original on March 7, 2016.

- Tau, Byron (December 4, 2012). "White House clarifies Puerto Rico stance". Politico. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "Pierluisi Introduces Historic Legislation" Archived September 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Puerto Rico Report, May 15, 2013. Retrieved on May 15, 2013.

- "Sen. Martin Heinrich Presents Bill Seeking Puerto Rico Statehood" Archived February 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Fox News Latino, February 12, 2014. Retrieved on February 14, 2014.

- "U.S. approves funds for referendum on Puerto Rico's status". January 16, 2014. Archived from the original on January 20, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- "Make room for 51st star? Spending bill includes $2.5 million for vote on Puerto RIco statehood". January 22, 2014. Archived from the original on January 1, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "What's a Free Associated State?". Puerto Rico Report. Puerto Rico Report. February 3, 2017. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- "Puerto Rico Statehood, Independence, or Free Association Referendum (2017)". Ballotpedia. BALLOTPEDIA. February 6, 2017. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

With my vote, I make the initial request to the Federal Government to begin the process of the decolonization through: (1) Free Association: Puerto Rico should adopt a status outside of the Territory Clause of the Constitution of the United States that recognizes the sovereignty of the People of Puerto Rico. The Free Association would be based on a free and voluntary political association, the specific terms of which shall be agreed upon between the United States and Puerto Rico as sovereign nations. Such agreement would provide the scope of the jurisdictional powers that the People of Puerto Rico agree to confer to the United States and retain all other jurisdictional powers and authorities. Under this option the American citizenship would be subject to negotiation with the United States Government; (2) Proclamation of Independence, I demand that the United States Government, in the exercise of its power to dispose of territory, recognize the national sovereignty of Puerto Rico as a completely independent nation and that the United States Congress enact the necessary legislation to initiate the negotiation and transition to the independent nation of Puerto Rico. My vote for Independence also represents my claim to the rights, duties, powers, and prerogatives of independent and democratic republics, my support of Puerto Rican citizenship, and a "Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation" between Puerto Rico and the United States after the transition process

- Wyss, Jim. "Will Puerto Rico become the newest star on the American flag?". Miami Herald. Miami. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- Coto, Danica (February 3, 2017). "Puerto Rico gov approves referendum in quest for statehood". The Washington Post. DC. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- "- The Washington Post". Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 17, 2017.

- "U.S. Territories". Archived from the original on February 9, 2007. Retrieved February 9, 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)." DOI Office of Insular Affairs. February 9, 2007.

- "DEFINITIONS OF INSULAR AREA POLITICAL ORGANIZATIONS". Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) Office of Insular Affairs. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- "Commission on Decolonization 2014". Guampedia. Guampedia. December 3, 2016. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- Raymundo, Shawn (December 8, 2016). "Commission to launch series of decolonization meetings". Pacific Daily News. Pacific Daily News. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- "Could the community decide reunifying the Marianas?". Archived from the original on July 28, 2017.

- mvariety. "Guam, NMI municipal officials seek non-binding reunification referendum". Marianas Variety.

- "KUAM.com-KUAM News: On Air. Online. On Demand". www.kuam.com.

- "Secretary-General Urges Concrete Action to Advance Decolonization Agenda as Pacific Regional Seminar Convenes". United Nations. United Nations. May 31, 2016. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

"Let us seize this opportunity to identify concrete actions to advance the decolonization agenda," Mr. Ban said ... according to the United Nations Charter and relevant General Assembly resolutions, a full measure of self-government could be achieved through independence, integration or free association with another State. The choice should be the result of the freely expressed will and desire of the peoples of the Non-Self-Governing Territories.

- "Secretary-General Urges Concrete Action to Advance Decolonization Agenda as Pacific Regional Seminar Convenes". United Nations. United Nations. May 31, 2016. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- https://www.upi.com/Archives/1984/07/28/Vote-on-statehood-possible-in-US-Virgin-Islands/4460459835200/ Vote on statehood possible in U.S. Virgin Islands. July 28, 1984. Upi.com (archives). Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "American Samoa to explore US statehood. Radionz.co.nz. Retrieved 30 January 2018". Radionz.co.nz. August 25, 2005. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- "The future prospects for American Samoa's political status. June 19, 2017. Fili Sagapolutele. Retrieved 30 January 2018". Samoanews.com. June 19, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- "The Federalist No. 43". Constitution.org. October 18, 1998. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- D.C. Statehood: Not Without a Constitutional Amendment Archived April 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, August 27, 1993, The Heritage Foundation.

- James, Randy (February 26, 2009). "A Brief History of Washington D.C". Time. Archived from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- Craig, Tim (January 15, 2013). "Obama to use D.C. 'taxation without representation' license plates". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- Levine, Jon (December 28, 2019). "White House removes DC's protest license plates from Trump's limo".

- "D.C. statehood vote to make history in the House — and that's about all". NBC News.

- Richards, Mark David (Spring–Summer 2004). "The Debates over the Retrocession of the District of Columbia, 1801–2004" (PDF). Washington History. Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 18, 2009.

- Delgadillo, Natalie; Kurzius, Rachel; Sadon, Rachel (September 18, 2019). "The Past, Present, And (Potential) Future Of D.C. Statehood, Explained". DCist. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Austermuhle, Martin. "Mayor Wants Statehood Vote This Year By D.C. Residents". WAMU 88.5. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- Giambrone, Andrew. "D.C. Statehood Commission Will Release Draft Constitution Next Friday". Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on May 29, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- Kinney, Jen. "Welcome, New Columbia? D.C. Drafts 51st State Constitution". Next City. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- "DC Voters Elect Gray to Council, Approve Statehood Measure". 4 NBC Washington. November 8, 2016. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- "Council Tosses 'New Columbia,' Changes Constitution To 'The State Of Washington D.C.'".

- https://statehood.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/statehood/publication/attachments/Eric-Shaw-Boundary-Testimony-for-NCSC.pdf

- https://statehood.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/statehood/publication/attachments/Constitution-of-the-State-of-Washington-DC.pdf

- https://statehood.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/statehood/publication/attachments/Map-of-the-State-of-Washington-DC.pdf

- CNN, Haley Byrd. "House Democrats pass DC statehood bill Friday". CNN.

- "House Resolution 51: Washington, D.C. Admission Act". 116th Congress. June 26, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020. }}

- News, A. B. C. "House votes to grant statehood to District of Columbia". ABC News.

- Hudak, John (June 25, 2020). "The politics and history of the D.C. statehood vote".

- "4 U.S. Code § 2 - Same; additional stars". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- "'Top Ten' American Flag Myths". The American Legion. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- Atencia, Romulo (June 27, 2012). "Statehood". Catanduanes Tribune. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013.

- "Facts about Nationalist Party: place in Philippine history, as discussed in Philippines: The period of U.S. influence". eb.com. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- "A Collaborative Philippine Leadership". U.S. Library of Congress. countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on October 15, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- Kamm, Henry (June 14, 1981). "MARCOS ELECTION FOE PRESSES FOR U.S. STATEHOOD". The New York Times. United States. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- Marco Garrido (January 29, 2004). "An American president of the Philippines?". Asian Times. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

The perennial presidential candidate Ely Pamatong banks on this allure, campaigning, as he does, on a platform of US statehood for the Philippines.

- Soberano, Rawlein G. (1976). "The Philippine Statehood Movement: A Resurrected Illusion, 1970–1972". The Southeast Asian Studies. 13 (4): 580–587. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- Francisco, Luzviminda (1973). "The First Vietnam: the U.S.-Philippine War of 1899". Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. 5 (4): 15. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- Wheeler, Gerald E. (May 1964). "The Movement to Reverse Philippine Independence". Pacific Historical Review. 33 (2): 167–181. doi:10.2307/3636594. JSTOR 3636594.

- Lawson, Gary; Guy Seidman (2004). The constitution of empire: territorial expansion and American legal history. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10231-4. Archived from the original on November 6, 2017.

- Jim Nach (1979–1980). "The Philippine Statehood Movement of 1971–1972". Cornell University Library. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- "The rise of secessionist movements". Archived from the original on November 23, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- "Constitution for the United States of America". 1787. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- "A tale of two counties". the Economist. March 1, 2011. Archived from the original on November 25, 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- Pierce, Tony (July 11, 2011). "'South California' proposed as 51st state by Republican supervisor". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "California to split into six states? Plan may get on ballot!". CBS news. February 25, 2014. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- Jim Miller, "Six Californias initiative fails to make 2016 ballot" Archived September 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The Sacramento Bee, 09/12/2014.

- Helsel, Phil (June 13, 2018). "Proposal to split California into three states earns spot on November ballot". nbcnews.com. NBC News. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

Voters in the massive state of California, touted as having an economy larger than most countries, could decide whether to support a plan calling for The Golden State to be split into three. An initiative that would direct the governor to seek Congressional approval to divide California into three states has enough valid signatures to be eligible for the Nov. 6 ballot, the Secretary of State's office said Tuesday. If the initiative is not withdrawn, it will be qualified for the ballot on June 28. Even if approved by voters, it faces the hurdle of approval by Congress.

- ""CAL 3" Initiative to Partition California Reaches Unprecedented Milestone" (PDF) (Press release). Cal3. April 11, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- Dolan, Maura (July 18, 2018). "Measure to split California into three states removed from ballot by the state Supreme Court". www.latimes.com. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_9,_Three_States_Initiative_(2018) Supreme Court removes Prop 9, the Three States Initiative, from ballot

- Romano, Analisa (June 6, 2013). "Weld County commissioners propose formation of new state, North Colorado". The Greeley Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- Whaley, Monte (November 6, 2013). "51st state question answered "no" in 6 of 11 counties contemplating secession". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- "Capital News Service wire feed". Journalism.umd.edu. February 20, 1998. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Huriash, Lisa J. (May 6, 2008). "North Lauderdale wants to split Florida into two states". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Erbentraut, Joseph (November 22, 2011). "Bill Mitchell, Illinois State Representative, Proposes Separating Cook County From Rest Of State (POLL)". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 25, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "EDITORIAL: A scramble for statehood". Washington Times. August 22, 2013. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- "New York: Mailer for Mayor". Time. June 12, 1969. Archived from the original on November 16, 2010. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

- "Footnotes to History: van Zandt". Buckyogi.com. January 1, 1994. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- "Urban Legends Reference Pages: Texas Dividing into Five States". Snopes.com. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- "Texas Cities and Counties Name and Location Confusion". Texasescapes.com. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- "Footnotes to History- U to Z". Buckyogi.com. January 1, 1994. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- "Urban Legends Reference Pages: Texas Dividing into Five States". Snopes.com. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- "Texas Cities and Counties Name and Location Confusion". Texasescapes.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- Wyckoff, Theodore (1977). "The Navajo Nation Tomorrow: 51st State, Commonwealth, or...?". American Indian Law Review. 5: 267–297 – via JSTOR.

- "List of US States By Size".

- Aptheker, Herbert (December 1, 1974). A Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States: 1933–1945. IV: N–J. Citadel Press. pp. 84–86.

- Llorens, David (September 1968). "Black Separatism in Perspective". Ebony. Johnson Publishing Company. p. 89. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- Stephen Azzi, "Election of 1988". histori.ca.

- Shannon Proudfoot (September 25, 2008). "Tories ahead in tepid pool of election ads". Global News. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012.

- Carolyn Ryan, "The true north, strong and negative" Archived April 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. cbc.ca, 2006.

- Articles of Confederation, Article XI

- "The Fenian Raids". Doyle.com.au. September 15, 2001. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- J.L. Granatstein, Norman Hillmer. For Better or For Worse, Canada and the United States to the 1990s. Mississauga: Copp Clark Pitman, 1991.

- "Parti 51 leaders looks to U.S. for Quebec's future", The Stanstead Journal, p. 2, September 20, 1989

- "Annexation in the Modern Context". Annexation.ca. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- "Alberta would be richer if it shacked up with U.S., argues author | CBC News". CBC.

- "Braid: Talk of Alberta exit is out in the open again | Financial Post". December 12, 2018.

- "Western Canadians still feel more connected to their province than to country as a whole: Ipsos | Globalnews.ca". globalnews.ca. October 8, 2018.

- "The 1948 Referendums". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage. Memorial University of Newfoundland. 1997. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- "Yucatán, USA?". Yucatan Times. July 6, 2015. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- "Monthly Record of Current Events". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. XVIII. Harper and Brothers. 1859. p. 543. ISBN 978-0-938214-02-1.

- "The Cuban Scheme" (PDF). The New York Times. January 21, 1859. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- "U.S. eases Cuba trade and travel rules ahead of Obama visit". Reuters. March 15, 2016. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017.

- United Airlines

- "Dominica: The Push for Annexation with the United States". The Dominican.net. Archived from the original on July 6, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- "U.S. Senate: Art & History Home > Origins & Development > Powers & Procedures > Treaties". United States Senate. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- "Deepfreeze Defense". Time. January 27, 1947. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- "National Review May 7, 2001 "Let's Buy Greenland! – A complete missile-defense plan" By John J. Miller (National Review's National Political Reporter)". Archived from the original on October 30, 2004.

- Adam Hannestad (January 23, 2014). "13 eksperter skyder Grønlands drøm om selvstændighed i sænk" (in Danish). Politiken.dk. Archived from the original on January 24, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Jan Müller (January 25, 2014). "Serfrøðingar sáa iva um eitt sjálvstøðugt Grønland – Føroyski portalurin – portal.fo". Oljan.fo. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- "Oil and Gas in Greenland – Still on Ice?". andrewskurth.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- Malte Humpert. "The Arctic Institute – Center for Circumpolar Security Studies". thearcticinstitute.org. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- Thompson, Mark (January 16, 2010). "The U.S. Military in Haiti: A Compassionate Invasion". TIME. Washington. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- "LIHKG". LIHKG 討論區. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- "LIHKG". LIHKG 討論區. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- "LIHKG". LIHKG 討論區. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- %e7%be%8e%e5%88%a9%e5%a0%85%e5%b8%9d%e5%9c%8b. "如果香港係美國第51個州". 香港高登討論區. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- "香港討論區". 香港討論區. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- "New party seeks Hong Kong's independence, via return to British rule". Archived from the original on July 15, 2017.

- "British lawmaker to Beijing: Allow Hong Kong to rejoin Commonwealth - South China Morning Post". July 10, 2015. Archived from the original on July 10, 2015.

- "香港 加拿大 蘇格蘭 聯邦會唔會更實際? - MO's notebook 4G 黃世澤 的筆記簿". April 9, 2017. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- "There's a movement to turn Hong Kong back into a British colony". Archived from the original on July 31, 2017.

- "香港是屬於中華民國的一部份". 信報論壇. Archived from the original on July 24, 2017.

- "Let's make Iraq our 51st state!". our51ststate.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- "The Fifty-first State?". The Atlantic. November 2002. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- Matthew Engel (March 19, 2003). "Iraq, the 51st state". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on August 27, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- Friedman, Thomas L. (May 4, 2003). "Our New Baby". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- "Saddam & Osama SNL TV Funhouse cartoon transcript, Iraq as "East Dakota"". Snltranscripts.jt.org. Archived from the original on June 22, 2003. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- "San Francisco Peace Treaty". Universität Efurt. September 8, 1951. Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. (came into force on April 28, 1952).

- "Public Opinion, Market research". TVBS Poll Center. Archived from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2008. (MS Word document, Chinese, See item 4) August 19, 2003

- "Taiwan Civil Government". Civil-taiwan.org. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.