History of American newspapers

The history of American newspapers begins in the early 18th century with the publication of the first colonial newspapers. American newspapers began as modest affairs—a sideline for printers. They became a political force in the campaign for American independence. Following independence the first amendment to U.S. Constitution guaranteed freedom of the press. The U.S. Postal Service Act of 1792 provided substantial subsidies: Newspapers were delivered up to 100 miles for a penny and beyond for 1.5 cents, when first class postage ranged from six cents to a quarter.

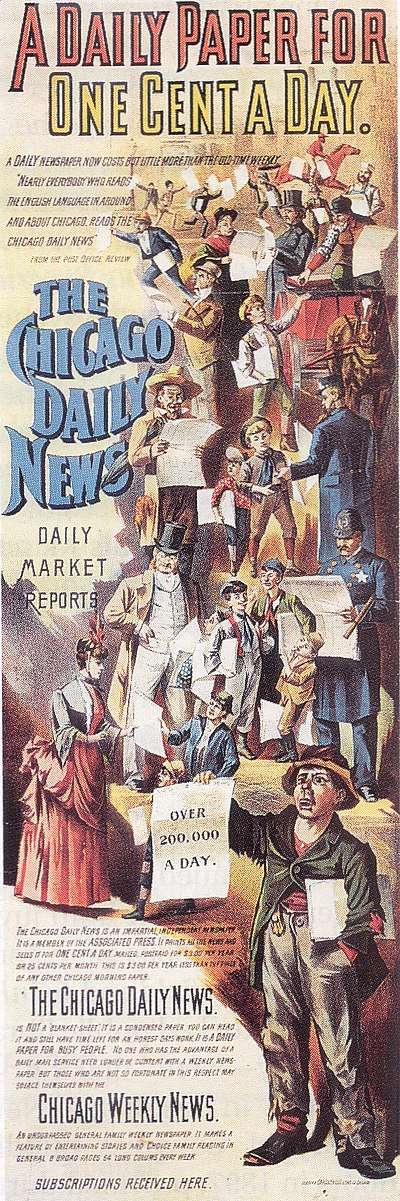

The American press grew rapidly during the First Party System (1790s-1810s) when both parties sponsored papers to reach their loyal partisans. From the 1830s onward, the Penny press began to play a major role in American journalism. Technological advancements such as the telegraph and faster printing presses in the 1840s also helped to expand the press of the nation as it experienced rapid economic and demographic growth. Editors typically became the local party spokesman, and hard-hitting editorials were widely reprinted.

By 1900 major newspapers had become profitable powerhouses of advocacy, muckraking and sensationalism, along with serious, and objective news-gathering. During the early 20th century, prior to rise of television, the average American read several newspapers per-day. Starting in the 1920s changes in technology again morphed the nature of American journalism as radio and later, television, began to play increasingly important competitive roles.

In the late 20th century, much of American journalism became housed in big media chains. With the coming of digital journalism in the 21st century, all newspapers faced a business crisis as readers turned to the Internet for sources and advertisers followed them.

Top row: The Union and Advertiser (William Purcell) - The Omaha Daily Bee (Edward Rosewater) - The Boston Daily Globe (Charles H. Taylor) - Boston Morning Journal (William Warland Clapp) - The Kansas City Times (Morrison Mumford) - The Pittsburgh Dispatch (M. O'Neill).

Middle row: Albany Evening Journal (John A. Sleicher) - The Milwaukee Sentinel (Horace Rublee) - The Philadelphia Record (William M. Singerly) - The New York Times (George Jones) - The Philadelphia Press (Charles Emory Smith) - The Daily Inter Ocean (William Penn Nixon) - The News and Courier (Francis Warrington Dawson).

Bottom row: Buffalo Express (James Newson Matthews) - The Daily Pioneer Press (Joseph A. Wheelock) - The Atlanta Constitution (Henry W. Grady & Evan Howell) - San Francisco Chronicle (Michael H. de Young) - The Washington Post (Stilson Hutchins)

Colonial period

On September 25, 1690, the first colonial newspaper in America, Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick, was published in Boston. However, it was suppressed after its first edition[1].

In 1704, the governor allowed The Boston News-Letter, a weekly, to be published, and it became the first continuously published newspaper in the colonies. Soon after, weekly papers began publishing in New York and Philadelphia.

Merchants published mainly commercial papers. For example, The Boston Daily Advertiser reported on ship arrivals and departures.

Prior to the 1830s, a majority of US newspapers were aligned with a political party or platform. Political parties would sponsor anonymous political figures in The Federal Republican and Daily Gazette. This was called partisan press and was not unbiased in opinion.[2]

The first editors discovered readers loved it when they criticized the local governor; the governors discovered they could shut down the newspapers. The most dramatic confrontation came in New York in 1734, where the governor brought John Peter Zenger to trial for criminal libel after the publication of satirical attacks. The jury acquitted Zenger, who became the iconic American hero for freedom of the press. The result was an emerging tension between the media and the government. By the mid-1760s, there were 24 weekly newspapers in the 13 colonies (only New Jersey was lacking one), and the satirical attack on government became common practice in American newspapers.[3]

The New England Courant

It was James Franklin (1697–1735), Benjamin Franklin's older brother, who first made a news sheet something more than a garbled mass of stale items, "taken from the Gazette and other Public Prints of London" some six months late. Instead, he launched a third newspaper, The New England Courant." His associates were known as the Hell-Fire Club; they succeeded in publishing a distinctive newspaper that annoyed the New England elite while proving entertaining and establishing a kind of literary precedent. Instead of filling the first part of the Courant with the tedious conventionalities of governors' addresses to provincial legislatures, James Franklin's club wrote essays and satirical letters modeled on The Spectator, which first appeared in London ten years earlier. After the more formal introductory paper on some general topic, such as zeal or hypocrisy or honor or contentment, the facetious letters of imaginary correspondents commonly fill the remainder of the Courant's first page. Timothy Turnstone addresses flippant jibes to Justice Nicholas Clodpate in the first extant number of the Courant. Tom Pen-Shallow quickly follows, with his mischievous little postscript: "Pray inform me whether in your Province Criminals have the Privilege of a Jury." Tom Tram writes from the moon about rumors of a certain "villainous Postmaster". (The Courant was always perilously close to legal difficulties and had, besides, a lasting feud with the town postmaster.) Ichabod Henroost complains of a gadding wife. Abigail Afterwit would like to know when the editor of the rival paper, the Gazette, "intends to have done printing the Carolina Addresses to their Governor, and give his Readers Something in the Room of them, that will be more entertaining." Homespun Jack deplores the fashions in general and small waists in particular. Some of these papers represent native wit, with only a general approach to the model; others are little more than paraphrases of The Spectator. And sometimes a Spectator paper is inserted bodily, with no attempt at paraphrase whatever. They also published poetry, histories, autobiographies, etc.[4]

Ben Franklin, journalist [Benjamin Franklin] saw the printing press as a device to instruct colonial Americans in moral virtue. Frasca argues he saw this as a service to God, because he understood moral virtue in terms of actions, thus, doing good provides a service to God. Despite his own moral lapses, Franklin saw himself as uniquely qualified to instruct Americans in morality. He tried to influence American moral life through the construction of a printing network based on a chain of partnerships from the Carolinas to New England. Franklin thereby invented the first newspaper chain, It was more than a business venture, for like many publishers since, he believed that the press had a public-service duty.[5]

When Franklin established himself in Philadelphia, shortly before 1730, the town boasted three "wretched little" news sheets, Andrew Bradford's American Mercury, and Samuel Keimer's Universal Instructor in all Arts and Sciences and Pennsylvania Gazette. This instruction in all arts and sciences consisted of weekly extracts from Chambers's Universal Dictionary. Franklin quickly did away with all this when he took over the Instructor, and made it The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Gazette soon became Franklin's characteristic organ, which he freely used for satire, for the play of his wit, even for sheer excess of mischief or of fun. From the first he had a way of adapting his models to his own uses. The series of essays called "The Busy-Body," which he wrote for Bradford's American Mercury in 1729, followed the general Addisonian form, already modified to suit homelier conditions. The thrifty Patience, in her busy little shop, complaining of the useless visitors who waste her valuable time, is related to the ladies who address Mr. Spectator. The Busy-Body himself is a true Censor Morum, as Isaac Bickerstaff had been in the Tatler. And a number of the fictitious characters, Ridentius, Eugenius, Cato, and Cretico, represent traditional 18th-century classicism. Even this Franklin could use for contemporary satire, since Cretico, the "sowre Philosopher", is evidently a portrait of Franklin's rival, Samuel Keimer.

As time went on, Franklin depended less on his literary conventions, and more on his own native humor. In this there is a new spirit—not suggested to him by the fine breeding of Addison, or the bitter irony of Swift, or the stinging completeness of Pope. The brilliant little pieces Franklin wrote for his Pennsylvania Gazette have an imperishable place in American literature.

The Pennsylvania Gazette, like most other newspapers of the period was often poorly printed. Franklin was busy with a hundred matters outside of his printing office, and never seriously attempted to raise the mechanical standards of his trade. Nor did he ever properly edit or collate the chance medley of stale items that passed for news in the Gazette. His influence on the practical side of journalism was minimal. On the other hand, his advertisements of books show his very great interest in popularizing secular literature. Undoubtedly his paper contributed to the broader culture that distinguished Pennsylvania from her neighbors before the Revolution. Like many publishers, Franklin built up a book shop in his printing office; he took the opportunity to read new books before selling them.

Franklin had mixed success in his plan to establish an inter-colonial network of newspapers that would produce a profit for him and disseminate virtue.[6] He began in Charleston, South Carolina in 1731. After the second editor died his widow Elizabeth Timothy took over and made it a success, 1738–46. She was one of colonial era's first woman printers.[7] For three decades Franklin maintained a close business relationship with her and her son Peter who took over in 1746.[8] The Gazette had a policy of impartiality in political debates, while creating the opportunity for public debate, which encouraged others to challenge authority. Editor Peter Timothy avoided blandness and crude bias, and after 1765 increasingly took a patriotic stand in the growing crisis with Great Britain.[9]

However, Franklin's Connecticut Gazette (1755–68) proved unsuccessful.[10]

The Virginia Gazette

Early theatrical notices may also be followed in The Virginia Gazette, a paper of unusual excellence, edited by William Parks in Williamsburg, the old capital of Virginia. Here The Busy-Body, The Recruiting Officer, and The Beaux' Stratagem were all performed, often by amateurs, though professionals were known as early as 1716 in Williamsburg. Life in Williamsburg in 1736 had a more cosmopolitan quality than in other towns. A sprightly essay-serial called The Monitor, which fills the first page of The Virginia Gazette for twenty-two numbers, probably reflects not only the social life of the capital, but also the newer fashion in such periodical work. It is dramatic in method, with vividly realized characters who gossip and chat over games of piquet or at the theatre. The Beaux' Stratagem, which had been played in Williamsburg three weeks before, is mentioned as delightful enough to make one of the ladies commit the indiscretion of giggling. The Monitor represents a kind of light social satire unusual in the colonies.[11]

Politics in the later newspapers

After 1750, general news became accessible, and the newspapers show more and more interest in public affairs. The literary first page was no longer necessary, though occasionally used to cover a dull period. A new type of vigorous polemic gradually superseded the older essay. A few of the well-known conventions were retained, however. We still find the fictitious letter, with the fanciful signature, or a series of papers under a common title, such as The Virginia-Centinel, or Livingston's Watch-Tower. The former is a flaming appeal to arms, running through The Virginia Gazette in 1756, and copied into Northern papers to rouse patriotism against the French enemy. The expression of the sentiment, even thus early, seems national. Livingston's well-known Watch-Tower, a continuation of his pamphlet-magazine The Independent Reflector, has already the keen edge of the Revolutionary writings of fifteen and twenty years later. The fifty-second number even has one of the popular phrases of the Revolution: "Had I not sounded the Alarm, Bigotry would e'er now have triumphed over the natural Rights of British Subjects." (Gaine's Mercury in 1754–1755)

Revolutionary epoch and early national era: 1770–1820

(This section is based on Newspapers, 1775–1860 by Frank W. Scott)

Weekly newspapers in major cities and towns were strongholds of patriotism (although there were a few Loyalist papers). They printed many pamphlets, announcements, patriotic letters and pronouncements.[12] On the eve of Revolution Virginia had three separate weeklies at the same time named The Virginia Gazette—they all kept up a heavy fire against the king and his governors.[13]

The Massachusetts Spy and the Patriotic Press

Isaiah Thomas's Massachusetts Spy, published in Boston and Worcester, was constantly on the verge of being suppressed, from the time of its establishment in 1770 to 1776 and during the American Revolution. In 1771-73 the Spy featured the essays of several anonymous political commentators who called themselves "Centinel," "Mucius Scaevola" and "Leonidas." They spoke in the same terms about similar issues, kept Patriot polemics on the front page, and supported each other against attacks in progovernment papers. Rhetorical combat was a Patriot tactic that explained the issues of the day and fostered cohesiveness without advocating outright rebellion. The columnists spoke to the colonists as an independent people tied to Britain only by voluntary legal compact. The Spy soon carried radicalism to its logical conclusion. When articles from the Spy were reprinted in other papers, the country as a whole was ready for Tom Paine's Common Sense (in 1776).[14]

The turbulent years between 1775 and 1783 were a time of great trial and disturbance among newspapers. Interruption, suppression, and lack of support checked their growth substantially. Although there were forty-three newspapers in the United States when the treaty of peace was signed (1783), as compared with thirty-seven on the date of the battle of Lexington (1775), only a dozen remained in continuous operation between the two events, and most of those had experienced delays and difficulties through lack of paper, type, and patronage. Not one newspaper in the principal cities, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, continued publication throughout the war. When the colonial forces were in possession, royalist papers were suppressed, and at times of British occupation, revolutionary papers moved away, or were discontinued, or they became royalist, only to suffer at the next turn of military fortunes. Thus there was an exodus of papers from the cities along the coast to smaller inland places, where alone it was possible for them to continue without interruption. Scarcity of paper was acute; type worn out could not be replaced. The appearance of the newspapers deteriorated, and issues sometimes failed to appear at all. Mail service, never good, was poorer than ever; foreign newspapers, an important source of information, could be obtained but rarely; many of the ablest writers who had filled the columns with dissertations upon colonial rights and government were now otherwise occupied.

News from a distance was less full and regular than before; yet when great events happened, reports spread over the country with great rapidity, through messengers in the service of patriotic organizations. The quality of reporting was still imperfect. The Salem Gazette printed a full but colored account of the battle of Lexington, giving details of the burning, pillage, and barbarities charged to the British, and praising the militia who were filled with "higher sentiments of humanity." The Declaration of Independence was published by Congress, July 6, 1776, in the Philadelphia Evening Post, from which it was copied by most of the newspapers in the new nation; but some of them did not mention it until two weeks later, and even then found room for only a synopsis. When they were permitted to do so, they printed fairly full accounts of the proceedings of provincial assemblies and of Congress, which were copied widely, as were all official reports and proclamations. On the whole, however, a relatively small proportion of such material and an inadequate account of the progress of the war is found in the contemporaneous newspapers.

The general spirit of the time found fuller utterance in mottoes, editorials, letters, and poems. In the beginning, both editorials and communications urged united resistance to oppression, praised patriotism, and denounced tyranny; as events and public sentiment developed these grew more vigorous, often a little more radical than the populace. Later, the idea of independence took form, and theories of government were discussed. More interesting and valuable as specimens of literature than these discussions were the poems inspired by the stirring events of the time. Long narratives of battles and of heroic deaths were mingled with eulogies of departed heroes. Songs meant to inspire and thrill were not lacking. Humor, pathos, and satire sought to stir the feelings of the public. Much of the poetry of the Revolution is to be found in the columns of the newspapers, from the vivid and popular satires and narratives of Philip Freneau to the saddest effusions of the most commonplace schoolmaster.[15][16]

The newspapers of the Revolution were an effective force working towards the unification of sentiment, the awakening of a consciousness of a common purpose, interest, and destiny among the separate colonies, and of a determination to see the war through to a successful issue. They were more single-minded than the people themselves, and they bore no small share of the burden of arousing and supporting the often discouraged and indifferent public spirit. The New Jersey Journal became the second newspaper published in New Jersey. It was established by Shepard Kollock at his press during 1779 in the village of Chatham, New Jersey. This paper became a catalyst in the revolution. News of events came directly to the editor from Washington's headquarters in nearby Morristown, boosting the morale of the troops and their families, and he conducted lively debates about the efforts for independence with those who opposed and supported the cause he championed. Kollock later relocated the paper twice, until 1785, when he established his last publication location in Elizabeth under the same name. The Elizabeth Daily Journal ceased publication on January 2, 1992 after having been in continuous publication for 212 years, the fourth oldest newspaper published continuously in the United States.[17]

Many of the papers, however, which were kept alive or brought to life during the war could not adapt themselves to the new conditions of peace. Perhaps only a dozen of the survivors held their own in the new time, notably the Boston Gazette, which declined rapidly in the following decade, The Connecticut Courant of Hartford, The Providence Gazette, and The Pennsylvania Packet of Philadelphia, to which may be added such representative papers as the Massachusetts Spy, Boston's Independent Chronicle, the New York Journal and Packet, the Newport Mercury, the Maryland Gazette of Annapolis, the Pennsylvania Gazette and The Pennsylvania Journal, both of Philadelphia. Practically all were of four small pages, each of three or four columns, issued weekly. In 1783, the Pennsylvania Evening Post became the first American daily.[18] The next year, the Pennsylvania Packet was published three times a week, and the New York Journal twice a week, as were several of the papers begun in that year. There was a notable extension to new fields. In Vermont, where the first paper, established in 1781, had soon died, another arose in 1783; in Maine, two were started in 1785. In 1786, the first one west of the Alleghenies appeared at Pittsburgh, and following the westward tide of immigration the Kentucky Gazette was begun at Lexington in 1787.

Conditions were hardly more favorable to newspapers than during the recent conflict. The sources of news were much the same; the means of communication and the postal system were little improved. Newspapers were not carried in the mails but by favor of the postmen, and the money of one state was of dubious value in another. Consequently, circulations were small, rarely reaching a thousand; subscribers were slow in paying; and advertisements were not plentiful. Newspapers remained subject to provincial laws of libel, in accordance with the old common law, and were, as in Massachusetts for a short time in 1785, subject to special state taxes on paper or on advertisements. But public sentiment was growing strongly against all legal restrictions, and in general the papers practiced freedom, not to say license, of utterance.

With independence had come the consciousness of a great destiny. The collective spirit aroused by the war, though clouded by conflicting local difficulties, was intense, and the principal interest of the newspapers was to create a nation out of the loose confederation. Business and commerce were their next care; but in an effort to be all things to all men, the small page included a little of whatever might "interest, instruct, or amuse." Political intelligence occupied first place; news, in the modern sense, was subordinated. A new idea, quite as much as a fire, a murder, or a prodigy, was a matter of news moment. There were always a few items of local interest, usually placed with paragraphs of editorial miscellany. Correspondents, in return for the paper, sent items; private letters, often no doubt written with a view to such use, were a fruitful source of news; but the chief resource was the newspapers that every office received as exchanges, carried in the post free of charge, and the newspapers from abroad.

Partisan newspapers

Newspapers became a form of public property after 1800. Americans believed that as republican citizens they had a right to the information contained in newspapers without paying anything. To gain access readers subverted the subscription system by refusing to pay, borrowing, or stealing. Editors, however, tolerated these tactics because they wanted longer subscription lists. First, the more people read the newspaper, more attractive it would be to advertisers, who would purchase more ads and pay higher rates. A second advantage was that greater depth of coverage translated into political influence for partisan newspapers. Newspapers also became part of the public sphere when they became freely available at reading rooms, barbershops, taverns, hotels and coffeehouses.[19]

The editor, usually reflecting the sentiment of a group or a faction, began to emerge as a distinct power. He closely followed the drift of events and expressed vigorous opinions. But as yet the principal discussions were contributed not by the editors but by "the master minds of the country." The growing importance of the newspaper was shown in the discussions preceding the Federal Convention, and notably in the countrywide debate on the adoption of the Constitution, in which the newspaper largely displaced the pamphlet. When Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay united to produce the Federalist Essays, they chose to publish them in The Independent Journal and The Daily Advertiser, from which they were copied by practically every paper in America long before they were made into a book.

When the first Congress assembled March 4, 1789, the administration felt the need of a paper, and, under the influence of Hamilton, John Fenno issued at New York, April 15, the first number of The Gazette of the United States, the earliest of a series of administration organs. The editorship of the Gazette later fell to Joseph Dennie, who had previously made a success of The Farmer's Weekly Museum and would later found The Port Folio, two of the most successful newspapers of the era.[20] The seat of government became the journalistic center of the country, and as long as party politics remained the staple news interest the administration organs and their opponents were the chief sources of news for the papers of the country.

Partisan bitterness increased during the last decade of the century as the First Party System took shape. The parties needed newspapers to communicate with their voters. New England papers were generally Federalist; in Pennsylvania there was a balance; in the West and South the Republican press predominated. Though the Federalists were vigorously supported by such able papers as Russell's Columbian Centinel in Boston, Isaiah Thomas's Massachusetts Spy, The Connecticut Courant, and, after 1793, Noah Webster's daily Minerva (soon renamed Commercial Advertiser) in New York, the Gazette of the United States, which in 1790 followed Congress and the capital to Philadelphia, was at the center of conflict, "a paper of pure Toryism", as Thomas Jefferson said, "disseminating the doctrines of monarchy, aristocracy, and the exclusion of the people." To offset the influence of this, Jefferson and Madison induced Philip Freneau, who had been editing The Daily Advertiser in New York, to set up a "half weekly", to "go through the states and furnish a Whig [Republican] vehicle of intelligence." Freneau's National Gazette, which first appeared October 31, 1791, soon became the most outspoken critic of the administration of Adams, Hamilton, and Washington, and an ardent advocate of the French Revolution. Fenno and Freneau, in the Gazette of the United States and the National Gazette, at once came to grips, and the campaign of personal and party abuse in partisan news reports, in virulent editorials, in poems and skits of every kind, was echoed from one end of the country to the other. The National Gazette closed in 1793 due to circulation problems and the political backlash against Jefferson and Madison's financial involvement in founding the paper.[21]

The other Republican paper of primary importance was the Aurora General Advertiser, founded by Ben Franklin's grandson and heir, Benjamin Franklin Bache, on October 2, 1790. The Aurora, published from Franklin Court in Philadelphia, was the most strident newspaper of its time, attacking John Adams' anti-democratic policies on a daily basis. No paper is thought to have given Adams more trouble than the Aurora. His wife, Abigail, wrote frequent letters to her sister and others decrying what she considered the slander spewing forth from the Aurora. Jefferson credited the Aurora with averting a disastrous war with France, and laying the groundwork for his own election. Following Bache's death (the result of his staying in Philadelphia during a yellow fever epidemic, while he was awaiting trial under the Sedition Act), William Duane, an immigrant from Ireland, led the paper until 1822 (and married Bache's widow, following the death of his own wife in the same Yellow Fever epidemic). Like Freneau, Bache and Duane were involved in a daily back-and-forth with the Federalist editors, especially Fenno and Cobbett.

Noah Webster, strapped for money, accepted an offer in late 1793 from Alexander Hamilton of $1,500 to move to New York City and edit a Federalist newspaper. In December he founded New York's first daily newspaper, American Minerva (later known as The Commercial Advertiser). He edited it for four years, writing the equivalent of 20 volumes of articles and editorials. He also published the semi-weekly publication, The Herald, A Gazette for the country (later known as The New York Spectator). As a partisan he soon was denounced by the Jeffersonian Republicans as "a pusillanimous, half-begotten, self-dubbed patriot", "an incurable lunatic", and "a deceitful newsmonge ... Pedagogue and Quack." Fellow Federalist Cobbett labeled him "a traitor to the cause of Federalism", calling him "a toad in the service of sans-culottism", "a prostitute wretch", "a great fool, and a barefaced liar", "a spiteful viper", and "a maniacal pedant." The master of words was distressed. Even the use of words like "the people", "democracy", and "equality" in public debate, bothered him for such words were "metaphysical abstractions that either have no meaning, or at least none that mere mortals can comprehend."

The first party newspapers were full of vituperation. As one historian comments,

It was with the newspaper editors, however, on both sides that a climax of rancorous and venomous abuse was reached. Of the Federalist editors, the most voluminous masters of scurrility were William Cobbett of Porcupine's Gazette and John Ward Fenno of the United States Gazette, at Philadelphia; Noah Webster of the American Minerva, at New York; and at Boston, Benjamin Russell of the Columbian Centinel, Thomas Paine of the Federal Orrery, and John Russell of the Boston Gazette. Chief of these was Cobbett, whose control of abusive epithet and invective may be judged from the following terms applied by him to his political foes, the Jacobins: "refuse of nations"; "yelper of the Democratic kennels"; "vile old wretch"; "tool of a baboon"; "frog-eating, man-eating, blood-drinking cannibals"; "I say, beware, ye under-strapping cut-throats who walk in rags and sleep amidst filth and vermin; for if once the halter gets round your flea-bitten necks, howling and confessing will come too late." He wrote of the "base and hellish calumnies" propagated by the Jacobins, and of "tearing the mask from the artful and ferocious villains who, owing to the infatuation of the poor, and the supineness of the rich, have made such fearful progress in the destruction of all that is amiable and good and sacred among men." Among the milder examples of his description of Jacobins was the following:

"Where the voice of the people has the most weight in public affairs, there it is most easy to introduce novel and subversive doctrines. In such States too, there generally, not to say always, exists a party who, from the long habit of hating those who administer the Government, become the enemies of the Government itself, and are ready to sell their treacherous services to the first bidder. To these descriptions of men, the sect of the Jacobins have attached themselves in every country they have been suffered to enter. They are a sort of flies, that naturally settle on the excremental and corrupted parts of the body politic ... The persons who composed this opposition, and who thence took the name of Anti-Federalists, were not equal to the Federalists, either in point of riches or respectability. They were in general, men of bad moral characters embarrassed in their private affairs, or the tools of such as were. Men of this caste naturally feared the operation of a Government imbued with sufficient strength to make itself respected, and with sufficient wisdom to exclude the ignorant and wicked from a share in its administration."[22]

This decade of violence was nevertheless one of development in both the quality and the power of newspapers. News reporting was extended to new fields of local affairs, and the intense rivalry of all too numerous competitors awoke the beginnings of that rush for the earliest reports, which was to become the dominant trait in American journalism. The editor evolved into a new type. As a man of literary skill, or a politician, or a lawyer with a gift for polemical writing, he began to supersede the contributors of essays as the strongest writer on the paper. Much of the best writing, and of the rankest scurrility, be it said, was produced by editors born and trained abroad, like Bache of the Aurora, Cobbett, Cooper, Gales, Cheetham, Callender, Lyon, and Holt. Of the whole number of papers in the country towards the end of the decade, more than one hundred and fifty, at least twenty opposed to the administration were conducted by aliens. The power wielded by these anti-administration editors impressed John Adams, who in 1801 wrote: "If we had been blessed with common sense, we should not have been overthrown by Philip Freneau, Duane, Callender, Cooper, and Lyon, or their great patron and protector. A group of foreign liars encouraged by a few ambitious native gentlemen have discomfited the education, the talents, the virtues, and the prosperity of the country."

The most obvious example of that Federalist lack of common sense was the passage of the Alien and Sedition laws in 1798 to protect the government from the libels of editors. The result was a dozen convictions and a storm of outraged public opinion that threw the party from power and gave the Jeffersonian Republican press renewed confidence and the material benefit of patronage when the Republicans took control of the government in 1800. The Republican party was especially effective in building a network of newspapers in major cities to broadcast its statements and editorialize in its favor. Fisher Ames, a leading Federalist, blamed the newspapers for electing Jefferson: they were "an overmatch for any Government ... The Jacobins owe their triumph to the unceasing use of this engine; not so much to skill in use of it as by repetition."[23]

The newspapers continued primarily party organs; the tone remained strongly partisan, though it gradually gained poise and attained a degree of literary excellence and professional dignity. The typical newspaper, a weekly, had a paid circulation of 500. The growth of the postal system, with the free transportation of newspapers locally and statewide, allowed the emergence of powerful state newspapers that closely reflected, and shaped, party views.

Growth

The number and geographical distribution of newspapers grew apace. In 1800 there were between 150 and 200; by 1810 there were 366, and during the next two decades the increase was at least equally rapid.[24] With astonishing promptness the press followed the sparse population as it trickled westward and down the Ohio or penetrated the more northerly forests. By 1835 papers had spread to the Mississippi River and beyond, from Texas to St. Louis, throughout Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and into Wisconsin. These pioneer papers, poorly written, poorly printed, and partisan often beyond all reason, served a greater than a merely local purpose in sending weekly to every locality their hundreds of messages of good and evil report, of politics and trade, of weather and crops, that helped immeasurably to bind the far-flung population into a nation.[25][26] Every congressman wrote regularly to his own local paper; other correspondents were called upon for like service, and in some instances the country editors established extensive and reliable lines of intelligence; but most of them depended on the bundle of exchanges from Washington, Philadelphia, and New York, and reciprocally the city papers made good use of their country exchanges.[27] ref>David M. Ryfe, "News, culture and public life: A study of 19th-century American journalism." Journalism Studies 7.1 (2006): 60–77. [ online]</ref>

As the number of cities of 8,000 or more population grew rapidly so too the daily newspapers were increasing in number. The first had appeared in Philadelphia and New York in 1784 and 1785; in 1796 one appeared in Boston. By 1810 there were twenty-seven in the country—one in the city of Washington, five in Maryland, seven in New York, nine in Pennsylvania, three in South Carolina, and two in Louisiana. As early as 1835 the Detroit Free Press began its long career.[28][29]

The press in the Party System: 1820–1890

(This section is based on Newspapers, 1775–1860 by Frank W. Scott)

The political and journalistic situation made the administration organ one of the characteristic features of the period. Fenno's Gazette had served the purpose for Washington and Adams; but the first great example of the type was the National Intelligencer established in October 1800, by Samuel Harrison Smith, to support the administration of Jefferson and of successive presidents until after Jackson it was thrown into the opposition, and The United States Telegraph, edited by Duff Green, became the official paper. It was replaced at the close of 1830 by a new paper, The Globe, under the editorship of Francis P. Blair, one of the ablest of all ante-bellum political editors, who, with John P. Rives, conducted it until the changing standards and conditions in journalism rendered the administration organ obsolescent. The Globe was displaced in 1841 by another paper called The National Intelligencer, which in turn gave way to The Madisonian. Thomas Ritchie was in 1845 called from his long service on The Richmond Enquirer to found, on the remains of The Globe, the Washington Union, to speak for the Polk administration and to reconcile the factions of democracy. Neither the Union nor its successors, which maintained the semblance of official support until 1860, ever occupied the commanding position held by the Telegraph and The Globe, but for forty years the administration organs had been the leaders when political journalism was dominant. Their influence was shared and increased by such political editors as M. M. Noah and James Watson Webb of the New York Courier and Enquirer, Solomon Southwick of the Albany Register, Edwin Croswell, who edited The Argus and who, supported by Martin Van Buren and others, formed what was known as the "Albany Regency." The "Regency", the Richmond "Junta", which centered in the Enquirer, and the "Kitchen Cabinet" headed by the editor of The Globe, formed one of the most powerful political and journalistic cabals that the country has ever known. Their decline, in the late thirties, was coincident with great changes, both political and journalistic, and though successors arose, their kind was not again so prominent or influential. The newspaper of national scope was passing away, yielding to the influence of the telegraph and the railroad, which robbed the Washington press of its claim to prestige as the chief source of political news. At the same time politics was losing its predominating importance. The public had many other interests, and by a new spirit and type of journalism was being trained to make greater and more various demands upon the journalistic resources of its papers.

The administration organ presents but one aspect of a tendency in which political newspapers generally gained in editorial individuality, and both the papers and their editors acquired greater personal and editorial influence. The beginnings of the era of personal journalism were to be found early in the 19th century. Even before Nathan Hale had shown the way to editorial responsibility, Thomas Ritchie, in the Richmond Enquirer in the second decade of the century, had combined with an effective development of the established use of anonymous letters on current questions a system of editorial discussion that soon extended his reputation and the influence of his newspaper far beyond the boundaries of Virginia. Washington Barrow and the Nashville Banner, Amos Kendall and The Argus of Western America, G. W. Kendall and the New Orleans Picayune, John M. Francis and the Troy Times, and Charles Hammond and the Cincinnati Gazette, to mention but a few among many, illustrate the rise of editors to individual power and prominence in the third and later decades. Notable among these political editors was John Moncure Daniel, who just before 1850 became editor of the Richmond Examiner and soon made it the leading newspaper of the South. Perhaps no better example need be sought of brilliant invective and literary pungency in American journalism just prior to and during the Civil War than in Daniel's contributions to the Examiner.

Though it could still be said that "too many of our gazettes are in the hands of persons destitute at once of the urbanity of gentlemen, the information of scholars, and the principles of virtue", a fact due largely to the intensity of party spirit, the profession was by no means without editors who exhibited all these qualities, and put them into American journalism. William Coleman, for instance, who, encouraged by Alexander Hamilton, founded the New York Evening Post in 1801, was a man of high purposes, good training, and noble ideals. The Evening Post, reflecting variously the fine qualities of the editor, exemplified the improvement in tone and illustrated the growing importance of editorial writing, as did a dozen or more papers in the early decades of the century. Indeed, the problem most seriously discussed at the earliest state meetings of editors and publishers, held in the thirties, was that of improving the tone of the press. They tried to attain by joint resolution a degree of editorial self-restraint, which few individual editors had as yet acquired. Under the influence of Thomas Ritchie, vigorous and unsparing political editor but always a gentleman, who presided at the first meeting of Virginia journalists, the newspaper men in one state after another resolved to "abandon the infamous practice of pampering the vilest of appetites by violating the sanctity of private life, and indulging in gross personalities and indecorous language", and to "conduct all controversies between themselves with decency, decorum, and moderation." Ritchie found in the low tone of the newspapers a reason why journalism in America did not occupy as high a place in public regard as it did in England and France.

Editorials

The editorial page was assuming something of its modern form. The editorial signed with a pseudonym gradually died, but unsigned editorial comment and leading articles did not become an established feature until after 1814, when Nathan Hale made them a characteristic of the newly established Boston Daily Advertiser. From that time on they grew in importance until in the succeeding period of personal journalism they were the most vital part of the greater papers.

Penny Press

In the 1830s new high speed presses allowed the cheap printing of tens of thousands of papers a day. The problem was to sell them to a mass audience, which required new business techniques (such as rapid citywide delivery) and a new style of journalism that would attract new audiences. Politics, scandal, and sensationalism worked.[30][31]

James Gordon Bennett Sr. (1794–1872) took the lead in New York.[32] In a decade of unsuccessful effort as a political journalist he had become familiar with the increasing enterprise in news-gathering. He despised the upscale journalism of the day—the seriousness of tone, the phlegmatic dignity, the party affiliations, the sense of responsibility. He believed journalists were fools to think that they could best serve their own purposes by serving the politicians. As Washington correspondent for the New York Enquirer, he wrote vivacious, gossipy prattle, full of insignificant and entertaining detail, to which he added keen characterization and deft allusions. Bennett saw a public who would not buy a serious paper at any price, who had a vast and indiscriminate curiosity better satisfied with gossip than discussion, with sensation rather than fact, who could be reached through their appetites and passions. The idea that he did much to develop rested on the success of the one-cent press created by the establishment of the New York Sun in 1833. To pay at such a price these papers must have large circulations, sought among the public that had not been accustomed to buy papers, and gained by printing news of the street, shop, and factory. To reach this public Bennett began the New York Herald, a small paper, fresh, sprightly, terse, and "newsy". "In journalistic débuts of this kind", Bennett wrote, "many talk of principle—political principle, party principle—as a sort of steel trap to catch the public. We ... disdain ... all principle, as it is called, all party, all politics. Our only guide shall be good, sound, practical common sense, applicable to the business and bosoms of men engaged in every-day life."[33]

According to historian Robert C Bannister, Bennett was :

- A gifted and controversial editor. Bennett transformed the American newspaper. Expanding traditional coverage, the Harold provided sports reports, a society page, and advice to the lovelorn, soon permanent features of most metropolitan dailies. Bennett covered murders and sex scandals and delicious detail, faking materials when necessary.... His adroit use of telegraph, pony express, and even offshore ships to intercept European dispatches set high standards for rapid news gathering.[34]

Bannister also argues that Bednnett was a leading crusader against evils he perceived:

- Combining opportunism and reform, Bennett exposed fraud on Wall Street, attacked the Bank of the United States, and generally joined the Jacksonian assault on privilege. Reflecting a growing nativism, he published excerpts from the anti-catholic disclosures of "Maria Monk," and he greeted Know-Nothingism cordially. Defending labor unions in principle, he asssailed much union activity. Unable to condemn slavery outright, he opposed abolitionism.[35]

News was but a commodity, the furnishing of which was a business transaction only, which ignored the social responsibility of the press, "the grave importance of our vocation", prized of the elder journalists and of the still powerful six-cent papers. The Herald, like the Sun, was at once successful, and was remarkably influential in altering journalistic practices. The penny press expanded its coverage into "personals"—short paid paragraphs by men and women looking for companionship. They revealed people's intimate relationships to a public audience and allowed city folk to connect with and understand their neighbors in an increasingly anonymous metropolis. They included heavy doses of imagination and fiction, typically romantic, highly stylized. Sometimes the same person updated the paragraph regularly, making it like a serial short short story. Moralists were aghast, and warned of the ruin of young girls. (Commenting on censorship of books in the 1920s, New York Mayor Jimmy Walker said he had seen many girls ruined, but never by reading.) More worrisome to the elders they reflected a loss of community control over the city's youth, suggesting to Protestant leaders the need for agencies like the YMCA to provide wholesome companionship. Personals are still included in many papers and magazines into the 21st century.[36]

Specialty media

In a period of widespread unrest and change many specialized forms of journalism sprang up—religious, educational, agricultural, and commercial magazines proliferated.[37] The Catholic immigrants started arriving in large numbers and major dioceses sponsored their own newspapers. For example, between 1845 and 1861, the Diocese of St. Louis saw four newspapers come and go: the Catholic News-Letter (1845–48), The Shepherd of the Valley (1850–54), The St. Louis Daily Leader (1855–56), and the Western Banner (1858–61).[38] The Boston Pilot was the leading Irish Catholic paper whose news and editorials were reprinted often by other Catholic papers the leading Irish Catholic newspaper of the period. The paper tried to balance support of the Union with its opposition to emancipation, while maintaining Irish American patriotism.[39]

Evangelical Protestants began discussing temperance, prohibition, and Even broach the subject of votes for women.[40] Abolition of slavery after 1830 became a highly inflammatory topic promoted by evangelical Protestants in the North. The leading abolitionist newspaper was William Lloyd Garrison's Liberator, first issued January 1, 1831, which denounced slavery as a sin against God that had to be immediately stopped. Many abolitionist papers were excluded from the mails; their circulation was forcibly prevented in the South; in Boston, New York, Baltimore, Cincinnati, Alton, and elsewhere, editors were assaulted, offices were attacked and destroyed; rewards were offered in the South for the capture of Greeley and Garrison; in a few instances editors, like Lovejoy at Alton, lost their lives at the hands of mobs.[41]

Rural papers

Nearly every county seat, and most towns of more than 500 or 1000 population sponsored one or more weekly newspapers. Politics was of major interest, with the editor-owner typically deeply involved in local party organizations. However, the paper also contained local news, and presented literary columns and book excerpts that catered to an emerging middle class literate audience. A typical rural newspaper provided its readers with a substantial source of national and international news and political commentary, typically reprinted from metropolitan newspapers. Comparison of a subscriber list for 1849 with data from the 1850 census indicates a readership dominated by property owners but reflecting a cross-section of the population, with personal accounts suggesting the newspaper also reached a wider non-subscribing audience. In addition, the major metropolitan daily newspapers often prepared weekly editions for circulation to the countryside. Most famously the Weekly New York Tribune was jammed with political, economic and cultural news and features, and was a major resource for the Whig and Republican parties, as well as a window on the international world, and the New York and European cultural scenes.[42]

Newspapers of the Territories

The first newspaper to be published west of the Mississippi was the Missouri Gazette. Its starting issue was published on July 12, 1808 by Joseph Charless an Irish printer. Swayed by Meriweather Lewis to leave his home in Kentucky and start a new paper for the Missouri Territory Charles was identified by the paper's masthead as "Printer to the Territory".[43] The paper published advertisements for domestic help, notice for runaway slaves, public notices, and sales for merchandise like land plots or cattle. Newspapers like the Gazette were instrumental in the founding new territories and supporting their stability as they become states.

With westward expansion other territories, like Nebraska, followed in Lewis and Missouri's plan for territory stability and founded a newspaper alongside the opening of the Nebraska Territory in 1854. The Nebraska Palladium[44] was a rough newspaper that produced poetry and news from the East, ran advertisements, and created a space for emerging political editorials. that developed a sense of community and cultural influence in the territory. Produced during a time when pioneers were far removed from neighbors these early territorial papers brought a sense of community to the territories. Because of the information gap felt by new settlers of the territories such as Kansas, Michigan, Nebraska, and Oklahoma there was a mass startup numerous newspapers. Frank Luther Mott says, "Wherever a town sprang up, there a printer with a rude press and a 'shirt-tail-full of type' was sure to appear".[45] Competition was intense between the large number of pop-up papers and often the papers would fail within a year or be bought out by a rival.

Associated Press and impact of telegraphy

This idea of news and the newspaper for its own sake, the unprecedented aggressiveness in news-gathering, and the blatant methods by which the cheap papers were popularized aroused the antagonism of the older papers, but created a competition that could not be ignored. Systems of more rapid news-gathering (such as by "pony express") and distribution quickly appeared. Sporadic attempts at co-operation in obtaining news had already been made; in 1848 the Journal of Commerce, Courier and Enquirer, Tribune, Herald, Sun, and Express formed the New York Associated Press to obtain news for the members jointly. Out of this idea grew other local, then state, and finally national associations. European news, which, thanks to steamship service, could now be obtained when but half as old as before, became an important feature. In the forties several papers sent correspondents abroad, and in the next decade this field was highly developed.[46][47]

The telegraph, invented in 1844, quickly linked all major cities and most minor ones to a national network that provided news in a matter of minutes or hours rather than days or weeks. It transformed the news gathering business. Telegraphic columns became a leading feature. The Associated Press (AP) became the dominant factor in the distribution of news. The inland papers, in such cities as Chicago, Louisville, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and New Orleans, used AP dispatches to become became independent of papers in Washington and New York.[48][49] In general, only one newspaper in each city had the Associated Press franchise, and it dominated the market for national and international news. United Press was formed in the 1880s to challenge the monopoly. The growing number of chains each set up their own internal dissemination system.

Great editors

Out of the period of restless change in the 1830s there emerged a few great editors whose force and ability gave them and their newspapers an influence hitherto unequalled, and made the period between 1840 and 1860 that of personal journalism. These few men not only interpreted and reflected the spirit of the time, but were of great influence in shaping and directing public opinion. Consequently, the scope, character, and influence of newspapers was in the period immensely widened and enriched, and rendered relatively free from the worst subjection to political control.

Naturally, the outstanding feature of this personal journalism was the editorial. Rescued from the slough of ponderousness into which it had fallen in its abject and uninspired party service, the editorial was revived, invigorated, and endowed with a vitality that made it the center about which all other features of the newspaper were grouped. It was individual; however large the staff of writers, the editorials were regarded as the utterance of the editor. "Greeley says" was the customary preface to quotations from the Tribune, and indeed many editorials were signed. James Gordon Bennett, Sr., Samuel Bowles (1826–78), Horace Greeley (1811–72), and Henry J. Raymond (1820–69) who were the outstanding figures of the period. Of Bennett's influence something has already been said; especially, he freed his paper from party control. His power was great, but it came from his genius in gathering and presenting news rather than from editorial discussion, for he had no great moral, social or political ideals, and his influence, always lawless and uncertain, can hardly be regarded as characteristic of the period. Of the others named, and many besides, it could be said with approximate truth that their ideal was "a full presentation and a liberal discussion of all questions of public concernment, from an entirely independent position, and a faithful and impartial exhibition of all movements of interest at home and abroad." As all three were not only upright and independent, but in various measure gifted with the quality of statesmanship at once philosophical and practical, their newspapers were powerful molders of opinion at a critical period in the history of the nation.

The news field was immeasurably broadened; news style was improved; interviews, newly introduced, lent the ease and freshness of dialogue and direct quotation. There was a notable improvement in the reporting of business, markets, and finance. In a few papers the literary department was conducted by staffs as able as any today. A foreign news service was developed that in intelligence, fidelity, and general excellence reached the highest standard yet attained in American journalism. A favorite feature was the series of letters from the editor or other member of the staff who traveled and wrote of what he heard or saw. Bowles, Olmsted, Greeley, Bayard Taylor, Bennett, and many others thus observed life and conditions at home or abroad; and they wrote so entertainingly and to such purpose that the letters—those of Olmsted and Taylor, for instance—are still sources of entertainment or information.

The growth of these papers meant the development of great staffs of workers that exceeded in numbers anything dreamed of in the preceding period. Although later journalism has far exceeded in this respect the time we are now considering, still the scope, complexity, and excellence of our modern metropolitan journalism in all its aspects were clearly begun between 1840 and 1860.

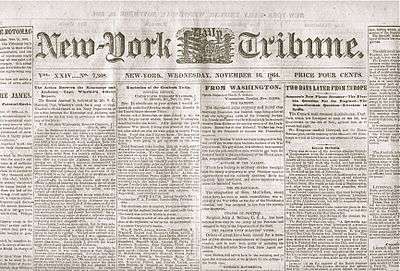

Greeley's New York Tribune

The New York Tribune under Horace Greeley exhibited the best features of the new and semi-independent personal journalism based upon political party supporters and inspired with an enthusiasm for service that is one of the fine characteristics of the period. In editing the New Yorker Greeley had acquired experience in literary journalism and in political news; his Jeffersonian and Log Cabin, were popular Whig campaign papers, had brought him into contact with politicians and made his reputation as an insightful, vigorous journalist. He was a staunch party man, therefore he was chosen to manage a party organ when one was needed to support the Whig administration of Harrison. The prospectus of the New York Tribune appeared April 3, 1841. Greeley's ambition was to make the Tribune not only a good party paper, but also the first paper in America, and he succeeded by imparting to it a certain idealistic character with a practical appeal that no other journal possessed. His sound judgment appeared in the unusually able staff that he gathered about him. Almost from the first, the staff that made the Tribune represented a broad catholicity of interests and tastes, in the world of thought as well as in the world of action, and a solid excellence in ability and in organization, which were largely the result of the genius of Greeley and over which he was the master spirit. It included Henry J. Raymond, who later became Greeley's rival on the Times, George M. Snow, George William Curtis, Charles A. Dana, Bayard Taylor, George Ripley, William H. Fry, Margaret Fuller, Edmund Quincy, and Charles T. Congdon. It is easy to understand how with such a group of writers the idea of the literary newspaper, which had been alive from the beginning of the century, should have advanced well-night to its greatest perfection.

The great popular strength of the Tribune doubtless lay in its disinterested sympathy with all the ideals and sentiments that stirred the popular mind in the forties and fifties. "We cannot afford", Greeley wrote, "to reject unexamined any idea which proposes to improve the moral, intellectual, or social condition of mankind." He pointed out that the proper course of an editor, in contrast to that of the time-server, was to have "an ear open to the plaints of the wronged and suffering, though they can never repay advocacy, and those who mainly support newspapers will be annoyed and often exposed by it; a heart as sensitive to oppression and degradation in the next street as if they were practiced in Brazil or Japan; a pen as ready to expose and reprove the crimes whereby wealth is amassed and luxury enjoyed in our own country as if they had only been committed by Turks or Pagans in Asia some centuries ago." In conformity with these principles Greeley lent his support to all proposals for ameliorating the condition of the labouring men by industrial education, by improved methods of farming, or even by such radical means as the socialistic Fourier Association. He strongly advocated the protective tariff because he believed that it was for the advantage of the workingman; and the same sympathy led him to give serious attention to the discussion of women's rights with special reference to the equal economic status of women. There were besides many lesser causes in which the Tribune displayed its spirit of liberalism, such as temperance reform, capital punishment, the Irish repeals, and the liberation of Hungary.

On the most important question of the time, the abolition of slavery, Greeley's views were intimately connected with party policy. His antipathy to slavery, based on moral and economic grounds, placed him from the first among the mildly radical reformers. But his views underwent gradual intensification. Acknowledged the most influential Whig party editor in 1844, he had by 1850 become the most influential anti-slavery editor—the spokesman not of Whigs merely but of a great class of Northerners who were thoroughly antagonistic to slavery but who had not been satisfied with either the non-political war of Garrison or the one-plank political efforts of the Free Soil party. This influence was greatly increased between 1850 and 1854 by some of the most vigorous and trenchant editorial writing America has ever known. The circulation of the Tribune in 1850 was, all told, a little less than sixty thousand, two-thirds of which was the Weekly. In 1854 the Weekly alone had a circulation of 112,000 copies. But even this figure is not the measure of the Tribune's peculiar influence, "for it was pre-eminently the journal of the rural districts, and one copy did service for many readers. To the people in the Adirondack wilderness it was a political bible, and the well-known scarcity of Democrats there was attributed to it. Yet it was as freely read by the intelligent people living on the Western Reserve of Ohio", (James Ford Rhodes) and in Wisconsin and Illinois. The work of Greeley and his associates in these years gave a new strength and a new scope and outlook to American journalism.

Greeley was a vigorous advocate of freedom of the press, especially in the 1830s and 1840s. He fought numerous libel lawsuits waged battles with the New York City postmaster, and shrugged off threats of duels and physical violence to his body. Greeley used his hard-hitting editorials to alert the public to dangers to press freedom. He would not tolerate any threats to freedom and democracy which curtailed the ability of the press to serve as a watchdog against corruption and a positive agency of social reform.[50]

After replacing Greeley Whitelaw Reid became the powerful long-time editor of the Tribune. He emphasized the importance of partisan newspapers in 1879:

- The true statesman and the really influential editor are those who are able to control and guide parties. ... There is an old question as to whether a newspaper controls public opinion or public opinion controls the newspaper. This at least is true: that editor best succeeds who best interprets the prevailing and the better tendencies of public opinion, and, who, whatever his personal views concerning it, does not get himself too far out of relations to it. He will understand that a party is not an end, but a means; will use it if it lead to his end, -- will use some other if that serve better, but will never commit the folly of attempting to reach the end without the means. ... Of all the puerile follies that have masqueraded before High Heaven in the guise of Reform, the most childish has been the idea that the editor could vindicate his independence only by sitting on the fence and throwing stones with impartial vigor alike at friend and foe.[51]

Henry Raymond and the New York Times

Henry Jarvis Raymond, who began his journalistic career on the Tribune and gained further experience in editing the respectable, old-fashioned, political Courier and Enquirer, perceived that there was an opening for a type of newspaper that should stand midway between Greeley, the moralist and reformer, and Bennett, the cynical, non-moral news-monger. He was able to interest friends in raising the hundred thousand dollars that he thought essential to the success of his enterprise. This sum is significant of the development of American daily journalism, for Greeley had started the Tribune only ten years earlier with a capital of one thousand dollars, and Bennett had founded the Herald with nothing at all. On this sound financial basis, Raymond began the career of the New York Times with his business partner George Jones on September 18, 1851, and made it a success from the outset. He perfected his news-gathering forces and brought into play his intimate acquaintance with men of affairs to open up the sources of information. Above all he set a new standard for foreign service. The American public never had a more general and intelligent interest in European affairs than in the middle years of the 19th century. The leading papers directed their best efforts toward sustaining and improving their foreign service, and Raymond used a brief vacation in Europe to establish for his paper a system of correspondence as trustworthy, if not as inclusive, as that of the Herald or Tribune. If our newspapers today are immeasurably in advance of those of sixty years ago in almost every field of journalism, there is only here and there anything to compare in worth with the foreign correspondence of that time. The men who wrote from the news centers of Europe were persons of wide political knowledge and experience, and social consequence. They had time and ability to do their work thoroughly, carefully, and intelligently, innocent of superficial effort toward sensation, of the practices of inaccurate brevity and irresponsible haste, which began with the laying of the Atlantic cable.

The theory of journalism announced by Raymond in the Times marks another advance over the party principles of his predecessors. He thought that a newspaper might assume the rôle now of a party paper, now of an organ of non-partisan, independent thought, and still be regarded by the great body of its readers as steadily guided by principles of sincere public policy. An active ambition for political preferment prevented him from achieving this ideal. Although he professed conservatism only in those cases where conservatism was essential to the public good and radicalism in everything that might require radical treatment and radical reform, the spirit of opposition to the Tribune, as well as his temperamental leanings, carried him definitely to the conservative side. He was by nature inclined to accept the established order and make the best of it. Change, if it came, should come not through radical agitation and revolution, but by cautious and gradual evolution. The world needed brushing, not harrowing. Such ideas, as he applied them to journalism, appealed to moderate men, reflected the opinions of a large and influential class somewhere between the advanced thinkers and theorists and the mass of men more likely to be swayed by passions of approbation or protest than by reason.

It was the tone of the Times that especially distinguished it from its contemporaries. In his first issue Raymond announced his purpose to write in temperate and measured language and to get into a passion as rarely as possible. "There are few things in this world which it is worth while to get angry about; and they are just the things anger will not improve." In controversy he meant to avoid abusive language. His style was gentle, candid, and decisive, and achieved its purpose by facility, clearness, and moderation rather than by powerful fervor and invective. His editorials were generally cautious, impersonal, and finished in form. With abundant self-respect and courtesy, he avoided, as one of his coadjutors said, vulgar abuse of individuals, unjust criticism, or narrow and personal ideas. He had that degree and kind of intelligence that enabled him to appreciate two principles of modern journalism—the application of social ethics to editorial conduct and the maintenance of a comprehensive spirit. As he used them, these were positive, not negative virtues.

Raymond's contribution to journalism, then, was not the introduction of revolutionizing innovations in any department of the profession but a general improving and refining of its tone, a balancing of its parts, sensitizing it to discreet and cultivated popular taste. Taking The Times of London as his model, he tried to combine in his paper the English standard of trustworthiness, stability, inclusiveness, and exclusiveness, with the energy and news initiative of the best American journalism; to preserve in it an integrity of motive and a decorum of conduct such as he possessed as a gentleman.

Postwar trends

Newspapers continued to play a major political role. In rural areas, the weekly newspaper published in the county seat played a major role. In the larger cities, different factions of the party have their own papers.[52] During the Reconstruction era (1865-1877), leading editors increasingly turned against corruption represented by President Grant and his Republican Party. They strongly supported the third-party Liberal Republican movement of 1872, which nominated Horace Greeley for president.[53] The Democratic Party endorsed Greeley officially, but many Democrats could not accept the idea of voting for the man who had been their fiercest enemy for decades; he lost in a landslide. Most of the 430 Republican newspapers in the Reconstruction South were edited by scalawags (Southern born white men) – only 20 percent were edited by carpetbaggers (recent arrivals from the North who formed the opposing faction in the Republican Party. White businessmen generally boycotted Republican papers, which survived through government patronage.)[54][55]

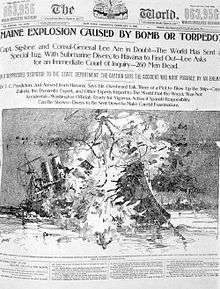

Newspapers were a major growth industry in the late nineteenth century. The number of daily papers grew from 971 to 2226, 1880 to 1900. Weekly newspapers were published in smaller towns, especially county seats, or for German, Swedish and other immigrant subscribers. They grew from 9,000 to 14,000, and by 1900 the United States published more than half of the newspapers in the world, with two copies per capita. Out on the frontier, the first need for a boom town was a newspaper. The new states of North and South Dakota by 1900 had 25 daily papers, and 315 weeklies. Oklahoma was still not a state, but it could boast of nine dailies and nearly a hundred weeklies. In the largest cities the newspapers competed fiercely, using newsboys to hawk copies and carriers to serve subscribers. Financially, the major papers depended on advertising, which paid in proportion to the circulation base. By the 1890s in New York City, especially during the Spanish–American War, circulations reached 1 million a day for Pulitzer's World and Hearst's Journal. While smaller papers relied on loyal Republican or Democratic readers who appreciated the intense partisanship of the editorials, the big-city papers realized they would lose half their potential audience by excessive partisanship, so they took a more ambiguous position, except at election time.[56]

Journalism was an attractive, but low-paid profession that drew ambitious young men starting their careers, and a few women. Editors were too busy condensing and rewriting and meeting deadlines to provide much tutelage. Reporters learned the craft by reading and discussing news stories among themselves, and following the tips and suggestions of more experienced colleagues. Reporters developed a personal rather than a professional code of ethics, and implemented their own work rules. Falsification was never allowed but increasingly the editors demanded sensationalistic perspectives, and juicy tidbits regardless of the news value.[57]

After the Civil War, there were several transitions in the newspaper industry. Many of the main founders of the modern press died, including Greeley, Raymond, Bennett, Bowles. and Bryant. Their successors continued the basic policies and approaches, but were less innovative. The civil war put a premium on news reporting, rather than editorials, and the news columns became increasingly important, with speed of the essence as multiple newspapers competed on the city streets for customers. The major papers issued numerous editions the day each with blaring headlines to capture attention. Reporting became more prestigious. There was no newspaper that exerted the national influence of Greeley's New York Tribune. Western cities, developed influential newspapers of their own in Chicago, San Francisco and St. Louis; the Southern press went into eclipse as the region lost its political influence and talented young journalists headed North for their careers. The Associated Press became increasingly important and efficient, producing a vast quantity of reasonably accurate, factual reporting on state and national events that editors used to service the escalating demand for news. Circulation growth was facilitated by new technology, such as the stereotype, by which 10 or more high-speed presses could print the same pages.[58]

With the movement of thousands of people with the conclusion of the Civil War new territories and states experienced and influx of settlers. The growth of a state and territory could be measured by the growth of the areas newspapers. With settlers pushing westward communities were considered stable if they had a newspaper publishing. This was a form of communication for all of the settlers and pioneers that lived in the far, rural communities. Larger, more established towns would begin to grow multiple newspapers. One of the papers would promote a Democratic view and the other Republican.[59]

Mass markets, yellow journalism and muckrakers, 1890–1920

Muckrakers

A muckraker is an American English term for a person who investigates and exposes issues of corruption. There were widely held values, such as political corruption, corporate crime, child labor, conditions in slums and prisons, unsanitary conditions in food processing plants (such as meat), fraudulent claims by manufacturers of patent medicines, labor racketeering, and similar topics. In British English however the term is applied to sensationalist scandal-mongering journalist, not driven by any social [original text missing; "journalist" above likely should be "journalism" or "a ... journalist."].

The term muckraker is most usually associated in America with a group of American investigative reporters, novelists and critics in the Progressive Era from the 1890s to the 1920s. It also applies to post 1960 journalists who follow in the tradition of those from that period. See History of American newspapers for Muckrakers in the daily press.

Muckrakers have most often sought, in the past, to serve the public interest by uncovering crime, corruption, waste, fraud and abuse in both the public and private sectors. In the early 1900s, muckrakers shed light on such issues by writing books and articles for popular magazines and newspapers such as Cosmopolitan, The Independent, Collier's Weekly and McClure's. Some of the most famous of the early muckrakers are Ida Tarbell, Lincoln Steffens, and Ray Stannard Baker.

History of term muckraker

President Theodore Roosevelt coined the term 'muckraker' in a 1906 speech when he likened the muckrakers to the Man with the Muckrake, a character in John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress (1678).[60]

Roosevelt disliked their relentless negativism and he attacked them for stretching the truth:

There are, in the body politic, economic and social, many and grave evils, and there is urgent necessity for the sternest war upon them. There should be relentless exposure of and attack upon every evil man whether politician or business man, every evil practice, whether in politics, in business, or in social life. I hail as a benefactor every writer or speaker, every man who, on the platform, or in book, magazine, or newspaper, with merciless severity makes such attack, provided always that he in his turn remembers that the attack is of use only if it is absolutely truthful.

Early muckrakers

- Nellie Bly (1864–1922) Ten Days in a Mad-House

- Thomas W. Lawson (1857–1924) Frenzied Finance (1906) on Amalgamated Copper stock scandal

- Fremont Older (1856–1935) San Francisco corruption and the case of Tom Mooney

- Lincoln Steffens (1866–1936) The Shame of the Cities (1904)

- Charles Edward Russell (1860–1941)—investigated Beef Trust, Georgia's prison

- Ida Minerva Tarbell (1857–1944) expose, The History of the Standard Oil Company

- Burton J. Hendrick (1870–1949)—"The Story of Life Insurance" May–November 1906 McClure's magazine

- Westbrook Pegler (1894–1969)—exposed crime in labor unions in the 1940s

- I.F. Stone (1907–1989)—McCarthyism and Vietnam War, published newsletter, I.F. Stone's Weekly

- George Seldes (1890–1995)—Freedom of the Press (1935) and Lords of the Press (1938), blacklisted during the 1950s period of McCarthyism

Contemporary muckrakers

- Wayne Barrett—investigative journalist, senior editor of the Village Voice; wrote on mystique and misdeeds in Rudy Giuliani's conduct as mayor of New York City, Grand Illusion: The Untold Story of Rudy Giuliani and 9/11 (2006)

- Richard Behar—investigative journalist, two-time winner of the 'Jack Anderson Award'. Anderson himself once praised Behar as "one of the most dogged of our watchdogs"

- Juan Gonzalez (journalist)—investigative reporter, columnist in New York Daily News; authored book on Rudy Giuliani and George W. Bush administration's handling of the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks in New York City and illnesses from Ground Zero dust: Fallout: The Environmental Consequences of the World Trade Center Collapse (2004)

- John Howard Griffin (1920–1980)—white journalist who disguised himself as a black man to write about racial injustice in the south

- Seymour Hersh—My Lai massacre, Israeli nuclear weapons program, Henry Kissinger, the Kennedys, 2003 invasion of Iraq, Abu Ghraib abuses

- Malcolm Johnson—exposed organized crime on the New York waterfront

- Jonathan Kwitny (1941–1998)—wrote numerous investigative articles for The Wall Street Journal

- Jack Newfield—muckraking columnist; wrote for New York Post; and wrote The Full Rudy: The Man, the Myth, the Mania [about Rudy Giuliani] (2003) and other titles

- Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein—breakthrough journalists for Washington Post on the Watergate scandal; authors of All the President's Men, non-fiction account of the scandal

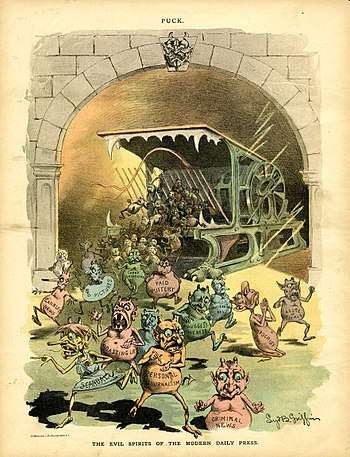

Yellow Journalism

Yellow journalism is a pejorative reference to journalism that features scandal-mongering, sensationalism, jingoism or other unethical or unprofessional practices by news media organizations or individual journalists.