Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 original states of the United States of America that served as its first constitution.[1] It was approved, after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777), by the Second Continental Congress on November 15, 1777, and sent to the states for ratification. The Articles of Confederation came into force on March 1, 1781, after being ratified by all 13 states. A guiding principle of the Articles was to preserve the independence and sovereignty of the states. The weak central government established by the Articles received only those powers which the former colonies had recognized as belonging to king and parliament.[2]

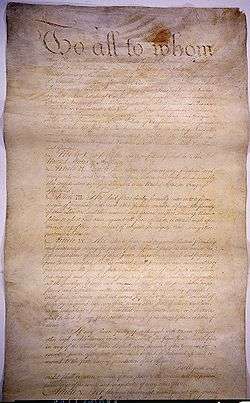

| Articles of Confederation | |

|---|---|

Page I of the Articles of Confederation | |

| Created | November 15, 1777 |

| Ratified | March 1, 1781 |

| Location | National Archives |

| Author(s) | Continental Congress |

| Signatories | Continental Congress |

| Purpose | First constitution for the United States; replaced by the current United States Constitution on March 4, 1789 |

The document provided clearly written rules for how the states' "league of friendship" would be organized. During the ratification process, the Congress looked to the Articles for guidance as it conducted business, directing the war effort, conducting diplomacy with foreign states, addressing territorial issues and dealing with Native American relations. Little changed politically once the Articles of Confederation went into effect, as ratification did little more than legalize what the Continental Congress had been doing. That body was renamed the Congress of the Confederation; but most Americans continued to call it the Continental Congress, since its organization remained the same.[2]

As the Confederation Congress attempted to govern the continually growing American states, delegates discovered that the limitations placed upon the central government rendered it ineffective at doing so. As the government's weaknesses became apparent, especially after Shays' Rebellion, some prominent political thinkers in the fledgling union began asking for changes to the Articles. Their hope was to create a stronger government. Initially, some states met to deal with their trade and economic problems. However, as more states became interested in meeting to change the Articles, a meeting was set in Philadelphia on May 25, 1787. This became the Constitutional Convention. It was quickly agreed that changes would not work, and instead the entire Articles needed to be replaced.[3] On March 4, 1789, the government under the Articles was replaced with the federal government under the Constitution.[4] The new Constitution provided for a much stronger federal government by establishing a chief executive (the President), courts, and taxing powers.

Background and context

The political push to increase cooperation among the then-loyal colonies began with the Albany Congress in 1754 and Benjamin Franklin's proposed Albany Plan, an inter-colonial collaboration to help solve mutual local problems. Over the next two decades, some of the basic concepts it addressed would strengthen; others would weaken, especially in the degree of loyalty (or lack thereof) owed the Crown. Civil disobedience resulted in coercive and quelling measures, such as the passage of what the colonials referred to as the Intolerable Acts in the British Parliament, and armed skirmishes which resulted in dissidents being proclaimed rebels. These actions eroded the number of Crown Loyalists (Tories) among the colonials and, together with the highly effective propaganda campaign of the Patriot leaders, caused an increasing number of colonists to begin agitating for independence from the mother country. In 1775, with events outpacing communications, the Second Continental Congress began acting as the provisional government.

It was an era of constitution writing—most states were busy at the task—and leaders felt the new nation must have a written constitution; a "rulebook" for how the new nation should function. During the war, Congress exercised an unprecedented level of political, diplomatic, military and economic authority. It adopted trade restrictions, established and maintained an army, issued fiat money, created a military code and negotiated with foreign governments.[5]

To transform themselves from outlaws into a legitimate nation, the colonists needed international recognition for their cause and foreign allies to support it. In early 1776, Thomas Paine argued in the closing pages of the first edition of Common Sense that the "custom of nations" demanded a formal declaration of American independence if any European power were to mediate a peace between the Americans and Great Britain. The monarchies of France and Spain, in particular, could not be expected to aid those they considered rebels against another legitimate monarch. Foreign courts needed to have American grievances laid before them persuasively in a "manifesto" which could also reassure them that the Americans would be reliable trading partners. Without such a declaration, Paine concluded, "[t]he custom of all courts is against us, and will be so, until, by an independence, we take rank with other nations."[6]

Beyond improving their existing association, the records of the Second Continental Congress show that the need for a declaration of independence was intimately linked with the demands of international relations. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution before the Continental Congress declaring the colonies independent; at the same time, he also urged Congress to resolve "to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances" and to prepare a plan of confederation for the newly independent states. Congress then created three overlapping committees to draft the Declaration, a model treaty, and the Articles of Confederation. The Declaration announced the states' entry into the international system; the model treaty was designed to establish amity and commerce with other states; and the Articles of Confederation, which established "a firm league" among the thirteen free and independent states, constituted an international agreement to set up central institutions for the conduct of vital domestic and foreign affairs.[7]

Drafting

On June 12, 1776, a day after appointing a committee to prepare a draft of the Declaration of Independence, the Second Continental Congress resolved to appoint a committee of 13 to prepare a draft of a constitution for a union of the states. The committee met frequently, and chairman John Dickinson presented their results to the Congress on July 12, 1776. Afterward, there were long debates on such issues as state sovereignty, the exact powers to be given to Congress, whether to have a judiciary, western land claims and voting procedures.[8] To further complicate work on the constitution, Congress was forced to leave Philadelphia twice, for Baltimore, Maryland, in the winter of 1776, and later for Lancaster then York, Pennsylvania, in the fall of 1777, to evade advancing British troops. Even so, the committee continued with its work.

The final draft of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was completed on November 15, 1777.[9] Consensus was achieved by: including language guaranteeing that each state retained its sovereignty, leaving the matter of western land claims in the hands of the individual states, including language stating that votes in Congress would be en bloc by state, and establishing a unicameral legislature with limited and clearly delineated powers.[10]

Ratification

The Articles of Confederation was submitted to the states for ratification in late November 1777. The first state to ratify was Virginia on December 16, 1777; 12 states had ratified the Articles by February 1779, 14 months into the process.[11] The lone holdout, Maryland, refused to go along until the landed states, especially Virginia, had indicated they were prepared to cede their claims west of the Ohio River to the Union.[12] It would be two years before the Maryland General Assembly became satisfied that the various states would follow through, and voted to ratify. During this time, Congress observed the Articles as its de facto frame of government. Maryland finally ratified the Articles on February 2, 1781. Congress was informed of Maryland's assent on March 1, and officially proclaimed the Articles of Confederation to be the law of the land.[11][13][14]

The several states ratified the Articles of Confederation on the following dates:[15]

| State | Date | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | December 16, 1777 | |

| 2 | February 5, 1778 | |

| 3 | February 6, 1778 | |

| 4 | February 9, 1778 | |

| 5 | February 12, 1778 | |

| 6 | February 26, 1778 | |

| 7 | March 4, 1778 | |

| 8 | March 5, 1778 | |

| 9 | March 10, 1778 | |

| 10 | April 5, 1778 | |

| 11 | November 19, 1778 | |

| 12 | February 1, 1779 | |

| 13 | February 2, 1781 | |

Article summaries

The Articles of Confederation contain a preamble, thirteen articles, a conclusion, and a signatory section. The individual articles set the rules for current and future operations of the confederation's central government. Under the Articles, the states retained sovereignty over all governmental functions not specifically relinquished to the national Congress, which was empowered to make war and peace, negotiate diplomatic and commercial agreements with foreign countries, and to resolve disputes between the states. The document also stipulates that its provisions "shall be inviolably observed by every state" and that "the Union shall be perpetual".

Summary of the purpose and content of each of the 13 articles:

- Establishes the name of the confederation with these words: "The stile of this confederacy shall be 'The United States of America.'"

- Asserts the sovereignty of each state, except for the specific powers delegated to the confederation government: "Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated."

- Declares the purpose of the confederation: "The said States hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defense, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretense whatever."

- Elaborates upon the intent "to secure and perpetuate mutual friendship and intercourse among the people of the different States in this union," and to establish equal treatment and freedom of movement for the free inhabitants of each state to pass unhindered between the states, excluding "paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice." All these people are entitled to equal rights established by the state into which they travel. If a crime is committed in one state and the perpetrator flees to another state, he will be extradited to and tried in the state in which the crime was committed.

- Allocates one vote in the Congress of the Confederation (the "United States in Congress Assembled") to each state, which is entitled to a delegation of between two and seven members. Members of Congress are to be appointed by state legislatures. No congressman may serve more than three out of any six years.

- Only the central government may declare war, or conduct foreign political or commercial relations. No state or official may accept foreign gifts or titles, and granting any title of nobility is forbidden to all. No states may form any sub-national groups. No state may tax or interfere with treaty stipulations already proposed. No state may wage war without permission of Congress, unless invaded or under imminent attack on the frontier; no state may maintain a peacetime standing army or navy, unless infested by pirates, but every State is required to keep ready, a well-trained, disciplined, and equipped militia.

- Whenever an army is raised for common defense, the state legislatures shall assign military ranks of colonel and below.

- Expenditures by the United States of America will be paid with funds raised by state legislatures, and apportioned to the states in proportion to the real property values of each.

- Powers and functions of the United States in Congress Assembled.

- Grants to the United States in Congress assembled the sole and exclusive right and power to determine peace and war; to exchange ambassadors; to enter into treaties and alliances, with some provisos; to establish rules for deciding all cases of captures or prizes on land or water; to grant letters of marque and reprisal (documents authorizing privateers) in times of peace; to appoint courts for the trial of pirates and crimes committed on the high seas; to establish courts for appeals in all cases of captures, but no member of Congress may be appointed a judge; to set weights and measures (including coins), and for Congress to serve as a final court for disputes between states.

- The court will be composed of jointly appointed commissioners or Congress shall appoint them. Each commissioner is bound by oath to be impartial. The court's decision is final.

- Congress shall regulate the post offices; appoint officers in the military; and regulate the armed forces.

- The United States in Congress assembled may appoint a president who shall not serve longer than one year per three-year term of the Congress.

- Congress may request requisitions (demands for payments or supplies) from the states in proportion with their population, or take credit.

- Congress may not declare war, enter into treaties and alliances, appropriate money, or appoint a commander in chief without nine states assented. Congress shall keep a journal of proceedings and adjourn for periods not to exceed six months.

- When Congress is in recess, any of the powers of Congress may be executed by "The committee of the states, or any nine of them", except for those powers of Congress which require nine states in Congress to execute.

- If Canada [referring to the British Province of Quebec] accedes to this confederation, it will be admitted.[16] No other colony could be admitted without the consent of nine states.

- Affirms that the Confederation will honor all bills of credit incurred, monies borrowed, and debts contracted by Congress before the existence of the Articles.

- Declares that the Articles shall be perpetual, and may be altered only with the approval of Congress and the ratification of all the state legislatures.

Congress under the Articles

The army

Under the Articles, Congress had the authority to regulate and fund the Continental Army, but it lacked the power to compel the States to comply with requests for either troops or funding. This left the military vulnerable to inadequate funding, supplies, and even food.[17] Further, although the Articles enabled the states to present a unified front when dealing with the European powers, as a tool to build a centralized war-making government, they were largely a failure; Historian Bruce Chadwick wrote:

George Washington had been one of the very first proponents of a strong federal government. The army had nearly disbanded on several occasions during the winters of the war because of the weaknesses of the Continental Congress. ... The delegates could not draft soldiers and had to send requests for regular troops and militia to the states. Congress had the right to order the production and purchase of provisions for the soldiers, but could not force anyone to supply them, and the army nearly starved in several winters of war.[18]

The Continental Congress, before the Articles were approved, had promised soldiers a pension of half pay for life. However Congress had no power to compel the states to fund this obligation, and as the war wound down after the victory at Yorktown the sense of urgency to support the military was no longer a factor. No progress was made in Congress during the winter of 1783–84. General Henry Knox, who would later become the first Secretary of War under the Constitution, blamed the weaknesses of the Articles for the inability of the government to fund the army. The army had long been supportive of a strong union.[19] Knox wrote:

The army generally have always reprobated the idea of being thirteen armies. Their ardent desires have been to be one continental body looking up to one sovereign. ... It is a favorite toast in the army, "A hoop to the barrel" or "Cement to the Union".[20]

As Congress failed to act on the petitions, Knox wrote to Gouverneur Morris, four years before the Philadelphia Convention was convened, "As the present Constitution is so defective, why do not you great men call the people together and tell them so; that is, to have a convention of the States to form a better Constitution."[20]

Once the war had been won, the Continental Army was largely disbanded. A very small national force was maintained to man the frontier forts and to protect against Native American attacks. Meanwhile, each of the states had an army (or militia), and 11 of them had navies. The wartime promises of bounties and land grants to be paid for service were not being met. In 1783, George Washington defused the Newburgh conspiracy, but riots by unpaid Pennsylvania veterans forced Congress to leave Philadelphia temporarily.[21]

The Congress from time to time during the Revolutionary War requisitioned troops from the states. Any contributions were voluntary, and in the debates of 1788, the Federalists (who supported the proposed new Constitution) claimed that state politicians acted unilaterally, and contributed when the Continental army protected their state's interests. The Anti-Federalists claimed that state politicians understood their duty to the Union and contributed to advance its needs. Dougherty (2009) concludes that generally the States' behavior validated the Federalist analysis. This helps explain why the Articles of Confederation needed reforms.[22]

Foreign policy

The 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended hostilities with Great Britain, languished in Congress for several months because too few delegates were present at any one time to constitute a quorum so that it could be ratified. Afterward, the problem only got worse as Congress had no power to enforce attendance. Rarely did more than half of the roughly sixty delegates attend a session of Congress at the time, causing difficulties in raising a quorum. The resulting paralysis embarrassed and frustrated many American nationalists, including George Washington. Many of the most prominent national leaders, such as Washington, John Adams, John Hancock, and Benjamin Franklin, retired from public life, served as foreign delegates, or held office in state governments; and for the general public, local government and self-rule seemed quite satisfactory. This served to exacerbate Congress's impotence.[23]

Inherent weaknesses in the confederation's frame of government also frustrated the ability of the government to conduct foreign policy. In 1786, Thomas Jefferson, concerned over the failure of Congress to fund an American naval force to confront the Barbary pirates, wrote in a diplomatic correspondence to James Monroe that, "It will be said there is no money in the treasury. There never will be money in the treasury till the Confederacy shows its teeth."[24]

Furthermore, the 1786 Jay–Gardoqui Treaty with Spain also showed weakness in foreign policy. In this treaty, which was never ratified, the United States was to give up rights to use the Mississippi River for 25 years, which would have economically strangled the settlers west of the Appalachian Mountains. Finally, due to the Confederation's military weakness, it could not compel the British army to leave frontier forts which were on American soil — forts which, in 1783, the British promised to leave, but which they delayed leaving pending U.S. implementation of other provisions such as ending action against Loyalists and allowing them to seek compensation. This incomplete British implementation of the Treaty of Paris would later be resolved by the implementation of Jay's Treaty in 1795 after the federal Constitution came into force.

Taxation and commerce

Under the Articles of Confederation, the central government's power was kept quite limited. The Confederation Congress could make decisions but lacked enforcement powers. Implementation of most decisions, including modifications to the Articles, required unanimous approval of all thirteen state legislatures.[25]

Congress was denied any powers of taxation: it could only request money from the states. The states often failed to meet these requests in full, leaving both Congress and the Continental Army chronically short of money. As more money was printed by Congress, the continental dollars depreciated. In 1779, George Washington wrote to John Jay, who was serving as the president of the Continental Congress, "that a wagon load of money will scarcely purchase a wagon load of provisions."[26] Mr. Jay and the Congress responded in May by requesting $45 million from the States. In an appeal to the States to comply, Jay wrote that the taxes were "the price of liberty, the peace, and the safety of yourselves and posterity."[27] He argued that Americans should avoid having it said "that America had no sooner become independent than she became insolvent" or that "her infant glories and growing fame were obscured and tarnished by broken contracts and violated faith."[28] The States did not respond with any of the money requested from them.

Congress had also been denied the power to regulate either foreign trade or interstate commerce and, as a result, all of the States maintained control over their own trade policies. The states and the Confederation Congress both incurred large debts during the Revolutionary War, and how to repay those debts became a major issue of debate following the War. Some States paid off their war debts and others did not. Federal assumption of the states' war debts became a major issue in the deliberations of the Constitutional Convention.

Accomplishments

Nevertheless, the Confederation Congress did take two actions with long-lasting impact. The Land Ordinance of 1785 and Northwest Ordinance created territorial government, set up protocols for the admission of new states and the division of land into useful units, and set aside land in each township for public use. This system represented a sharp break from imperial colonization, as in Europe, and it established the precedent by which the national (later, federal) government would be sovereign and expand westward—as opposed to the existing states doing so under their sovereignty.[29]

The Land Ordinance of 1785 established both the general practices of land surveying in the west and northwest and the land ownership provisions used throughout the later westward expansion beyond the Mississippi River. Frontier lands were surveyed into the now-familiar squares of land called the township (36 square miles), the section (one square mile), and the quarter section (160 acres). This system was carried forward to most of the States west of the Mississippi (excluding areas of Texas and California that had already been surveyed and divided up by the Spanish Empire). Then, when the Homestead Act was enacted in 1867, the quarter section became the basic unit of land that was granted to new settler-farmers.

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 noted the agreement of the original states to give up northwestern land claims, organized the Northwest Territory and laid the groundwork for the eventual creation of new states. While it didn't happen under the articles, the land north of the Ohio River and west of the (present) western border of Pennsylvania ceded by Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, eventually became the states of: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, and the part of Minnesota east of the Mississippi River. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 also made great advances in the abolition of slavery. New states admitted to the union in this territory would never be slave states.

No new states were admitted to the Union under the Articles of Confederation. The Articles provided for a blanket acceptance of the Province of Quebec (referred to as "Canada" in the Articles) into the United States if it chose to do so. It did not, and the subsequent Constitution carried no such special provision of admission. Additionally, ordinances to admit Frankland (later modified to Franklin), Kentucky, and Vermont to the Union were considered, but none were approved.

Presidents of Congress

Under the Articles of Confederation, the presiding officer of Congress—referred to in many official records as President of the United States in Congress Assembled—chaired the Committee of the States when Congress was in recess, and performed other administrative functions. He was not, however, an executive in the way the later President of the United States is a chief executive, since all of the functions he executed were under the direct control of Congress.[30]

There were 10 presidents of Congress under the Articles. The first, Samuel Huntington, had been serving as president of the Continental Congress since September 28, 1779.

| President | Term |

|---|---|

| Samuel Huntington | March 1, 1781 – July 10, 1781 |

| Thomas McKean | July 10, 1781 – November 5, 1781 |

| John Hanson | November 5, 1781 – November 4, 1782 |

| Elias Boudinot | November 4, 1782 – November 3, 1783 |

| Thomas Mifflin | November 3, 1783 – June 3, 1784 |

| Richard Henry Lee | November 30, 1784 – November 4, 1785 |

| John Hancock | November 23, 1785 – June 5, 1786 |

| Nathaniel Gorham | June 6, 1786 – November 3, 1786 |

| Arthur St. Clair | February 2, 1787 – November 4, 1787 |

| Cyrus Griffin | January 22, 1788 – November 15, 1788 |

The U.S. under the Articles

The peace treaty left the United States independent and at peace but with an unsettled governmental structure. The Articles envisioned a permanent confederation but granted to the Congress—the only federal institution—little power to finance itself or to ensure that its resolutions were enforced. There was no president, no executive agencies, no judiciary, and no tax base. The absence of a tax base meant that there was no way to pay off state and national debts from the war years except by requesting money from the states, which seldom arrived.[31][32] Although historians generally agree that the Articles were too weak to hold the fast-growing nation together, they do give credit to the settlement of the western issue, as the states voluntarily turned over their lands to national control.[33]

By 1783, with the end of the British blockade, the new nation was regaining its prosperity. However, trade opportunities were restricted by the mercantilism of the British and French empires. The ports of the British West Indies were closed to all staple products which were not carried in British ships. France and Spain established similar policies. Simultaneously, new manufacturers faced sharp competition from British products which were suddenly available again. Political unrest in several states and efforts by debtors to use popular government to erase their debts increased the anxiety of the political and economic elites which had led the Revolution. The apparent inability of the Congress to redeem the public obligations (debts) incurred during the war, or to become a forum for productive cooperation among the states to encourage commerce and economic development, only aggravated a gloomy situation. In 1786–87, Shays' Rebellion, an uprising of dissidents in western Massachusetts against the state court system, threatened the stability of state government.[34]

The Continental Congress printed paper money which was so depreciated that it ceased to pass as currency, spawning the expression "not worth a continental". Congress could not levy taxes and could only make requisitions upon the States. Less than a million and a half dollars came into the treasury between 1781 and 1784, although the governors had been asked for two million in 1783 alone.[35]

When John Adams went to London in 1785 as the first representative of the United States, he found it impossible to secure a treaty for unrestricted commerce. Demands were made for favors and there was no assurance that individual states would agree to a treaty. Adams stated it was necessary for the States to confer the power of passing navigation laws to Congress, or that the States themselves pass retaliatory acts against Great Britain. Congress had already requested and failed to get power over navigation laws. Meanwhile, each State acted individually against Great Britain to little effect. When other New England states closed their ports to British shipping, Connecticut hastened to profit by opening its ports.[36]

By 1787 Congress was unable to protect manufacturing and shipping. State legislatures were unable or unwilling to resist attacks upon private contracts and public credit. Land speculators expected no rise in values when the government could not defend its borders nor protect its frontier population.[37]

The idea of a convention to revise the Articles of Confederation grew in favor. Alexander Hamilton realized while serving as Washington's top aide that a strong central government was necessary to avoid foreign intervention and allay the frustrations due to an ineffectual Congress. Hamilton led a group of like-minded nationalists, won Washington's endorsement, and convened the Annapolis Convention in 1786 to petition Congress to call a constitutional convention to meet in Philadelphia to remedy the long-term crisis.[38]

Signatures

The Second Continental Congress approved the Articles for distribution to the states on November 15, 1777. A copy was made for each state and one was kept by the Congress. On November 28, the copies sent to the states for ratification were unsigned, and the cover letter, dated November 17, had only the signatures of Henry Laurens and Charles Thomson, who were the President and Secretary to the Congress.

The Articles, however, were unsigned, and the date was blank. Congress began the signing process by examining their copy of the Articles on June 27, 1778. They ordered a final copy prepared (the one in the National Archives), and that delegates should inform the secretary of their authority for ratification.

On July 9, 1778, the prepared copy was ready. They dated it and began to sign. They also requested each of the remaining states to notify its delegation when ratification was completed. On that date, delegates present from New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and South Carolina signed the Articles to indicate that their states had ratified. New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland could not, since their states had not ratified. North Carolina and Georgia also were unable to sign that day, since their delegations were absent.

After the first signing, some delegates signed at the next meeting they attended. For example, John Wentworth of New Hampshire added his name on August 8. John Penn was the first of North Carolina's delegates to arrive (on July 10), and the delegation signed the Articles on July 21, 1778.

The other states had to wait until they ratified the Articles and notified their Congressional delegation. Georgia signed on July 24, New Jersey on November 26, and Delaware on February 12, 1779. Maryland refused to ratify the Articles until every state had ceded its western land claims. Chevalier de La Luzerne, French Minister to the United States, felt that the Articles would help strengthen the American government. In 1780 when Maryland requested France provide naval forces in the Chesapeake Bay for protection from the British (who were conducting raids in the lower part of the bay), he indicated that French Admiral Destouches would do what he could but La Luzerne also “sharply pressed” Maryland to ratify the Articles, thus suggesting the two issues were related.[39]

On February 2, 1781, the much-awaited decision was taken by the Maryland General Assembly in Annapolis.[40] As the last piece of business during the afternoon Session, "among engrossed Bills" was "signed and sealed by Governor Thomas Sim Lee in the Senate Chamber, in the presence of the members of both Houses... an Act to empower the delegates of this state in Congress to subscribe and ratify the articles of confederation" and perpetual union among the states. The Senate then adjourned "to the first Monday in August next." The decision of Maryland to ratify the Articles was reported to the Continental Congress on February 12. The confirmation signing of the Articles by the two Maryland delegates took place in Philadelphia at noon time on March 1, 1781, and was celebrated in the afternoon. With these events, the Articles were entered into force and the United States of America came into being as a sovereign federal state.

Congress had debated the Articles for over a year and a half, and the ratification process had taken nearly three and a half years. Many participants in the original debates were no longer delegates, and some of the signers had only recently arrived. The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union were signed by a group of men who were never present in the Congress at the same time.

Signers

The signers and the states they represented were:

|

|

|

|

|

Roger Sherman (Connecticut) was the only person to sign all four great state papers of the United States: the Continental Association, the United States Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution.

Robert Morris (Pennsylvania) signed three of the great state papers of the United States: the United States Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution.

John Dickinson (Delaware), Daniel Carroll (Maryland) and Gouverneur Morris (New York), along with Sherman and Robert Morris, were the only five people to sign both the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution (Gouverneur Morris represented Pennsylvania when signing the Constitution).

Gallery

Original parchment pages of the Articles of Confederation, National Archives and Records Administration.

Preamble to Art. V, Sec. 1

Preamble to Art. V, Sec. 1 Art. V, Sec. 2 to Art. VI

Art. V, Sec. 2 to Art. VI Art. VII to Art. IX, Sec. 2

Art. VII to Art. IX, Sec. 2 Art. IX, Sec. 2 to Sec. 5

Art. IX, Sec. 2 to Sec. 5 Art. IX, Sec. 5 to Art. XIII, Sec. 2

Art. IX, Sec. 5 to Art. XIII, Sec. 2 Art. XIII, Sec. 2 to signatures

Art. XIII, Sec. 2 to signatures

Revision and replacement

On January 21, 1786, the Virginia Legislature, following James Madison's recommendation, invited all the states to send delegates to Annapolis, Maryland to discuss ways to reduce interstate conflict. At what came to be known as the Annapolis Convention, the few state delegates in attendance endorsed a motion that called for all states to meet in Philadelphia in May 1787 to discuss ways to improve the Articles of Confederation in a "Grand Convention." Although the states' representatives to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia were only authorized to amend the Articles, the representatives held secret, closed-door sessions and wrote a new constitution. The new Constitution gave much more power to the central government, but characterization of the result is disputed. The general goal of the authors was to get close to a republic as defined by the philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment, while trying to address the many difficulties of the interstate relationships. Historian Forrest McDonald, using the ideas of James Madison from Federalist 39, describes the change this way:

The constitutional reallocation of powers created a new form of government, unprecedented under the sun. Every previous national authority either had been centralized or else had been a confederation of sovereign states. The new American system was neither one nor the other; it was a mixture of both.[41]

In May 1786, Charles Pinckney of South Carolina proposed that Congress revise the Articles of Confederation. Recommended changes included granting Congress power over foreign and domestic commerce, and providing means for Congress to collect money from state treasuries. Unanimous approval was necessary to make the alterations, however, and Congress failed to reach a consensus. The weakness of the Articles in establishing an effective unifying government was underscored by the threat of internal conflict both within and between the states, especially after Shays' Rebellion threatened to topple the state government of Massachusetts.

Historian Ralph Ketcham comments on the opinions of Patrick Henry, George Mason, and other Anti-Federalists who were not so eager to give up the local autonomy won by the revolution:

Antifederalists feared what Patrick Henry termed the "consolidated government" proposed by the new Constitution. They saw in Federalist hopes for commercial growth and international prestige only the lust of ambitious men for a "splendid empire" that, in the time-honored way of empires, would oppress the people with taxes, conscription, and military campaigns. Uncertain that any government over so vast a domain as the United States could be controlled by the people, Antifederalists saw in the enlarged powers of the general government only the familiar threats to the rights and liberties of the people.[42]

Historians have given many reasons for the perceived need to replace the articles in 1787. Jillson and Wilson (1994) point to the financial weakness as well as the norms, rules and institutional structures of the Congress, and the propensity to divide along sectional lines.

Rakove (1988) identifies several factors that explain the collapse of the Confederation. The lack of compulsory direct taxation power was objectionable to those wanting a strong centralized state or expecting to benefit from such power. It could not collect customs after the war because tariffs were vetoed by Rhode Island. Rakove concludes that their failure to implement national measures "stemmed not from a heady sense of independence but rather from the enormous difficulties that all the states encountered in collecting taxes, mustering men, and gathering supplies from a war-weary populace."[43] The second group of factors Rakove identified derived from the substantive nature of the problems the Continental Congress confronted after 1783, especially the inability to create a strong foreign policy. Finally, the Confederation's lack of coercive power reduced the likelihood for profit to be made by political means, thus potential rulers were uninspired to seek power.

When the war ended in 1783, certain special interests had incentives to create a new "merchant state," much like the British state people had rebelled against. In particular, holders of war scrip and land speculators wanted a central government to pay off scrip at face value and to legalize western land holdings with disputed claims. Also, manufacturers wanted a high tariff as a barrier to foreign goods, but competition among states made this impossible without a central government.[44]

Legitimacy of closing down

Political scientist David C. Hendrickson writes that two prominent political leaders in the Confederation, John Jay of New York and Thomas Burke of North Carolina believed that "the authority of the congress rested on the prior acts of the several states, to which the states gave their voluntary consent, and until those obligations were fulfilled, neither nullification of the authority of congress, exercising its due powers, nor secession from the compact itself was consistent with the terms of their original pledges."[45]

According to Article XIII of the Confederation, any alteration had to be approved unanimously:

[T]he Articles of this Confederation shall be inviolably observed by every State, and the Union shall be perpetual; nor shall any alteration at any time hereafter be made in any of them; unless such alteration be agreed to in a Congress of the United States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every State.

On the other hand, Article VII of the proposed Constitution stated that it would become effective after ratification by a mere nine states, without unanimity:

The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States so ratifying the Same.

The apparent tension between these two provisions was addressed at the time, and remains a topic of scholarly discussion. In 1788, James Madison remarked (in Federalist No. 40) that the issue had become moot: "As this objection...has been in a manner waived by those who have criticised the powers of the convention, I dismiss it without further observation." Nevertheless, it is an interesting historical and legal question whether opponents of the Constitution could have plausibly attacked the Constitution on that ground. At the time, there were state legislators who argued that the Constitution was not an alteration of the Articles of Confederation, but rather would be a complete replacement so the unanimity rule did not apply.[46] Moreover, the Confederation had proven woefully inadequate and therefore was supposedly no longer binding.[46]

Modern scholars such as Francisco Forrest Martin agree that the Articles of Confederation had lost its binding force because many states had violated it, and thus "other states-parties did not have to comply with the Articles' unanimous consent rule".[47] In contrast, law professor Akhil Amar suggests that there may not have really been any conflict between the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution on this point; Article VI of the Confederation specifically allowed side deals among states, and the Constitution could be viewed as a side deal until all states ratified it.[48]

Final months

On July 3, 1788, the Congress received New Hampshire's all-important ninth ratification of the proposed Constitution, thus, according to its terms, establishing it as the new framework of governance for the ratifying states. The following day delegates considered a bill to admit Kentucky into the Union as a sovereign state. The discussion ended with Congress making the determination that, in light of this development, it would be "unadvisable" to admit Kentucky into the Union, as it could do so "under the Articles of Confederation" only, but not "under the Constitution".[49]

By the end of July 1788, 11 of the 13 states had ratified the new Constitution. Congress continued to convene under the Articles with a quorum until October.[50][51] On Saturday, September 13, 1788, the Confederation Congress voted the resolve to implement the new Constitution, and on Monday, September 15 published an announcement that the new Constitution had been ratified by the necessary nine states, set the first Wednesday in February 1789 for the presidential electors to meet and select a new president, and set the first Wednesday of March 1789 as the day the new government would take over and the government under the Articles of Confederation would come to an end.[52][53] On that same September 13, it determined that New York would remain the national capital.[52]

See also

References

- Jensen, Merrill (1959). The Articles of Confederation: An Interpretation of the Social-Constitutional History of the American Revolution, 1774–1781. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. xi, 184. ISBN 978-0-299-00204-6.

- Morison p. 279

- Kelley, Martin. "Why did the Articles of Confederation fail?". About Education. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- Rodgers, Paul (2011). United States Constitutional Law: An Introduction. McFarland. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-7864-6017-5.

- Wood, Gordon S. (1969). The Creation of the American Republic: 1776–1787. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 354–55.

- Paine, Thomas (January 14, 1776). "Common Sense". In Foner, Eric (ed.). Paine: Collected Writings. The Library of America. pp. 45–6. ISBN 978-1-4286-2200-5. (Collection published 1995.)

- Armitage, David (2004). "The Declaration of Independence in World Context". Magazine of History. Organization of American Historians. 18 (3): 61–66. doi:10.1093/maghis/18.3.61.

- Jensen. Articles of Confederation. pp. 127–84.

- Schwarz, Frederic D. (February–March 2006). "225 Years Ago". American Heritage. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009.

- "Maryland finally ratifies Articles of Confederation". history.com. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- "Articles of Confederation, 1777–1781". Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- Frederick D. Williams, Ed. The Northwest Ordinance: Essays on its Formulation, Provisions, and Legacy, p. 1782. MSU Press, (2012)

- Elliot, Jonathan (1836). The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution. 1 (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Editor on the Pennsylvania Avenue. p. 98. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- Mallory, John (1917). United States Compiled Statutes. 10. St. Paul: West Publishing Company. pp. 13044–5. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- Hough, Franklin Benjamin (1872). American Constitutions. Albany: Weed, Parsons, & Company. p. 10. References to a 1778 Virginia ratification are based on an error in the Journals of Congress: "The published Journals of Congress print this enabling act of the Virginia assembly under date of Dec. 15, 1778. This error has come from the MS. vol. 9 (History of Confederation), p. 123, Papers of the Continental Congress, Library of Congress." Dyer, Albion M. (2008) [1911]. First Ownership of Ohio Lands. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8063-0098-6.

- "Avalon Project – Articles of Confederation : March 1, 1781". avalon.law.yale.edu.

- Carp, E. Wayne (1980). To Starve the Army at Pleasure: Continental Army Administration and American Political Culture, 1775–1783. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4269-0.

- Chadwick p. 469. Phelps pp. 165–166. Phelps wrote:

- "It is hardly surprising, given their painful confrontations with a weak central government and the sovereign states, that the former generals of the Revolution as well as countless lesser officers strongly supported the creation of a more muscular union in the 1780s and fought hard for the ratification of the Constitution in 1787. Their wartime experiences had nationalized them."

- Puls pp. 174–176

- Puls p. 177

- Lodge, Henry Cabot (1893). George Washington, Vol. I. I.

- Dougherty, Keith L. (Spring 2009). "An Empirical Test of Federalist and Anti-Federalist Theories of State Contributions, 1775–1783". Social Science History. 33 (1): 47–74. doi:10.1215/01455532-2008-015.

- Ferling, John (2003). A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. Oxford University Press. pp. 255–259.

- Julian P. Boyd (ed.). "Editorial Note: Jefferson's Proposed Concert of Powers against the Barbary States". Founders Online. Washington, D.C.: National Archives. Retrieved April 21, 2018. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 10, June 22–December 31, 1786, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954, pp. 560–566]

- Jensen, Merrill (1950). The New Nation: A History of the United States During the Confederation, 1781–1789. Northeastern University Press. pp. 177–233. ISBN 978-0-930350-14-7.

- Stahr p. 105

- Stahr p. 107

- Stahr pp. 107–108

- Satō, Shōsuke (1886) [Digitized 2008]. History of the land question in the United States. Baltimore, Maryland: Isaac Friedenwald, for Johns Hopkins University. p. 352. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- Jensen, Merrill (1959). The Articles of Confederation: An Interpretation of the Social-Constitutional History of the American Revolution, 1774–1781. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-0-299-00204-6.

- Morris, Richard B. (1987). The Forging of the Union, 1781–1789. Harper & Row. pp. 245–66. ISBN 978-0-06-091424-0.

- Frankel, Benjamin (2003). History in Dispute: The American Revolution, 1763–1789. St James Press. pp. 17–24.

- McNeese, Tim (2009). Revolutionary America 1764–1799. Chelsea House Pub. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-60413-350-9.

- Murrin, John M. (2008). Liberty, Equality, Power, A History of the American People: To 1877. Wadsworth Publishing Company. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-111-83086-1.

- Jensen, Merrill (1959). The Articles of Confederation. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-299-00204-6.

- Ferling, John (2010). John Adams: A Life. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 257–8. ISBN 978-0-19-975273-7.

- Rakove, Jack N. (1988). "The Collapse of the Articles of Confederation". In Barlow, J. Jackson; Levy, Leonard W. & Masugi, Ken (eds.). The American Founding: Essays on the Formation of the Constitution. pp. 225–45.

- Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-101-20085-8.

- Sioussat, St. George L. (October 1936). "THE CHEVALIER DE LA LUZERNE AND THE RATIFICATION OF THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION BY MARYLAND, 1780–1781 With Accompanying Documents". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 60 (4): 391–418. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- "An ACT to empower the delegates". Laws of Maryland, 1781. February 2, 1781. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011.

- McDonald pg. 276

- Ketcham, Ralph (1990). Roots of the Republic: American Founding Documents Interpreted. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-945612-19-3.

- Rakove 1988 p. 230

- Hendrickson p. 154

- Hendrickson p. 153–154

- Maier, Pauline. Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788, p. 62 (Simon and Schuster, 2011).

- Martin, Francisco. The Constitution as Treaty: The International Legal Constructionalist Approach to the U.S. Constitution, p. 5 (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- Amar, Akhil. America's Constitution: A Biography, p. 517 (Random House 2012).

- Kesavan, Vasan (December 1, 2002). "When Did the Articles of Confederation Cease to Be Law". Notre Dame Law Review. 78 (1): 70–71. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- "America During the Age of Revolution, 1776–1789". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- Charles Lanman; Joseph M. Morrison (1887). Biographical Annals of the Civil Government of the United States. J.M. Morrison. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- Maier, Pauline (2010). Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788. Simon and Schuster. pp. 429–30. ISBN 978-0-684-86855-4.

- "Continental Congress Broadside Collection for 1778-Sep-13". Retrieved April 17, 2011.

Further reading

- Bernstein, R.B. (1999). "Parliamentary Principles, American Realities: The Continental and Confederation Congresses, 1774–1789". In Bowling, Kenneth R. & Kennon, Donald R. (eds.). Inventing Congress: Origins & Establishment Of First Federal Congress. pp. 76–108.

- Brown, Roger H. (1993). Redeeming the Republic: Federalists, Taxation, and the Origins of the Constitution. ISBN 978-0-8018-6355-4.

- Burnett, Edmund Cody (1941). The Continental Congress: A Definitive History of the Continental Congress From Its Inception in 1774 to March 1789.

- Chadwick, Bruce (2005). George Washington's War. Sourcebooks, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4022-2610-6.

- Feinberg, Barbara (2002). The Articles Of Confederation. Twenty First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-7613-2114-9.

- Greene, Jack & Pole, J.R., eds. (2003). A Companion to the American Revolution (2nd ed.).

- Hendrickson, David C. (2003). Peace Pact: The Lost World of the American Founding. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1237-8.

- Hoffert, Robert W. (1992). A Politics of Tensions: The Articles of Confederation and American Political Ideas. University Press of Colorado.

- Horgan, Lucille E. (2002). Forged in War: The Continental Congress and the Origin of Military Supply and Acquisition Policy. Praeger Pub Text. ISBN 978-0-313-32161-0.

- Jensen, Merrill (1959). The Articles of Confederation: An Interpretation of the Social-Constitutional History of the American Revolution, 1774–1781. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-00204-6.

- —— (1950). The New Nation. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-0-930350-14-7.

- —— (1943). "The Idea of a National Government During the American Revolution". Political Science Quarterly. 58 (3): 356–79. doi:10.2307/2144490. JSTOR 2144490.

- Jillson, Calvin & Wilson, Rick K. (1994). Congressional Dynamics: Structure, Coordination, and Choice in the First American Congress, 1774–1789. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2293-3.

- Klos, Stanley L. (2004). President Who? Forgotten Founders. Pittsburgh: Evisum, Inc. p. 261. ISBN 0-9752627-5-0.

- Main, Jackson T. (1974). Political Parties before the Constitution. W W Norton & Company Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-393-00718-3.

- McDonald, Forrest (1986). Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0311-5.

- Mclaughlin, Andrew C. (1935). A Constitutional History of the United States. Simon Publications. ISBN 978-1-931313-31-5.

- Morris, Richard (1988). The Forging of the Union, 1781–1789. New American Nation Series. HarperCollins Publishers.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Nevins, Allan (1924). The American States during and after the Revolution, 1775–1789. New York: Macmillan.

- Parent, Joseph M. (Fall 2009). "Europe's Structural Idol: An American Federalist Republic?". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (3): 513–535. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165x.2009.tb00658.x.

- Phelps, Glenn A. (2001). "The Republican General". In Higginbotham, Don (ed.). George Washington Reconsidered. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-2005-1.

- Puls, Mark (2008). Henry Knox: Visionary General of the American Revolution. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-8427-2.

- Rakove, Jack N. (1982). The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- —— (1988). "The Collapse of the Articles of Confederation". In Barlow, J. Jackson; Levy, Leonard W. & Masugi, Ken (eds.). The American Founding: Essays on the Formation of the Constitution. Greenwood Press. pp. 225–45. ISBN 0-313-25610-1.

- Van Cleve, George William (2017). We Have Not a Government: The Articles of Confederation and the Road to the Constitution. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-48050-3.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Articles of Confederation |

- Text version of the Articles of Confederation

- Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union

- Articles of Confederation and related resources, Library of Congress

- Today in History: November 15, Library of Congress

- United States Constitution Online—The Articles of Confederation

- Free Download of Articles of Confederation Audio

- Mobile friendly version of the Articles of Confederation