Children in the military

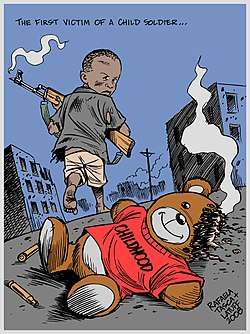

Children in the military are children (defined by the Convention on the Rights of the Child as people under the age of 18) who are associated with military organisations, such as state armed forces and non-state armed groups.[1] Throughout history and in many cultures, children have been involved in military campaigns.[2] For example, thousands of children participated on all sides of the First World War and the Second World War.[3][4][5][6] Children may be trained and used for combat, assigned to support roles such as porters or messengers, or used for tactical advantage as human shields or for political advantage in propaganda.[1][7]

| Part of a series on |

| Child soldiers |

|---|

| Main articles |

| Issues |

|

| Instances (examples) |

| Legal aspects |

| Movement to end the use of child soldiers |

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

|

|

|

Related

|

Children are easy targets for military recruitment due to their greater susceptibility to influence compared to adults.[8][9][2][10] Some are recruited by force while others choose to join up, often to escape poverty or because they expect military life to offer a rite of passage to maturity.[2][11][12][13][14]

Child recruits who survive armed conflict frequently suffer psychiatric illness, poor literacy and numeracy, and behavioral problems such as heightened aggression, leading to a high risk of poverty and unemployment in adulthood.[15] Research in the UK and US has also found that the enlistment of adolescent children, even when they are not sent to war, is accompanied by a higher risk of attempted suicide,[16][17] stress-related mental disorders,[18][19] alcohol abuse,[20][21] and violent behavior.[22][23][24]

A number of treaties have sought to curb the participation of children in armed conflicts. According to Child Soldiers International these agreements have helped to reduce child recruitment,[25] but the practice remains widespread and children continue to participate in hostilities around the world.[26][27] Some economically powerful nations continue to rely on military recruits aged 16 or 17, and the use of younger children in armed conflict has increased in recent years as militant movements and the groups fighting them recruited children in large numbers.[28]

History

History is filled with children who have been trained and used for fighting, assigned to support roles such as porters or messengers, used as sex slaves, or recruited for tactical advantage as human shields or for political advantage in propaganda.[1][7][29] In 1814, for example, Napoleon conscripted many teenagers for his armies.[30] Thousands of children participated on all sides of the First World War and the Second World War.[3][4][5][6] Children continued to be used throughout the 20th and early 21st century on every continent, with concentrations in parts of Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East.[31] Only since the turn of the millennium have international efforts begun to limit and reduce the military use of children.[14][32]

Current situation

State armed forces

Since the adoption in 2000 of the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (OPAC) the global trend has been towards restricting armed forces recruitment to adults aged 18 or over, known as the Straight-18 standard.[25][33] Most states with armed forces have opted in to OPAC, which also prohibits states that still recruit children from using them in armed conflict.[33]

Nonetheless, Child Soldiers International reported in 2018 that children under the age of 18 were still being recruited and trained for military purposes in 46 countries;[34] of these, most recruit from age 17, fewer than 20 recruit from age 16, and an unknown, smaller number, recruit younger children.[25][26][35] States that still rely on children to staff their armed forces include the world's three most populous countries (China, India, and the United States) and the most economically powerful (all G7 countries apart from Italy and Japan).[26] The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child and others have called for an end to the recruitment of children by state armed forces, arguing that military training, the military environment, and a binding contract of service are not compatible with children's rights and jeopardize healthy development during adolescence.[36][26][37][38]

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates hired child soldiers from Sudan (especially from Darfur) to fight against Houthis during the Yemeni Civil War (2015–present).[39][40][41]

Non-state armed groups

These include non-state armed Paramilitary organisations, using children such as militias, insurgents, terrorist organizations, guerrilla movements, ideologically or religiously-driven groups, armed liberation movements, and other types of quasi-military organisation. In 2017 the United Nations identified 14 countries where children were widely used by such groups: Afghanistan, Colombia,[42] Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Mali, Myanmar, Nigeria, Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen.[28][43]

Not all armed groups use children and approximately 60 have entered agreements to reduce or end the practice since 1999.[27] For example, by 2017, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) in the Philippines had released nearly 2,000 children from its ranks,[44] and in 2016, the FARC-EP guerrilla movement in Colombia agreed to stop recruiting children.[28] Other countries have seen the reverse trend, particularly Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria and Syria, where Islamist militants and groups opposing them have intensified their recruitment, training, and use of children.[28]

Global estimate

In 2003 P. W. Singer of the Brookings Institution estimated that child soldiers participate in about three-quarters of ongoing conflicts.[45] In the same year the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) estimated that most of these children were aged over 15, although some were younger.[46]

Today, due to the widespread military use of children in areas where armed conflict and insecurity prevent access by UN officials and other third parties, it is difficult to estimate how many children are affected.[47] In 2017 Child Soldiers International estimated that several tens of thousands of children, possibly more than 100,000, were in state- and non-state military organisations around the world,[47] and in 2018 the organisation reported that children were being used to participate in at least 18 armed conflicts.[34]

Rationale for the use of children

Despite children's physical and psychological underdevelopment relative to adults, there are many reasons why state- and non-state military organisations seek them out. Cited examples include:

- Peter W. Singer has suggested that the global proliferation of light automatic weapons, which children can easily handle, has made the use of children as direct combatants more viable.[48]

- Roméo Dallaire has pointed to the role of overpopulation in making children a cheap and accessible resource for military organisations.[49]

- Roger Rosenblatt has suggested that children are more willing than adults to fight for non-monetary incentives such as religion, honour, prestige, revenge and duty.[50]

- Several commentators, including Bernd Beber, Christopher Blattman, Dave Grossman, Michael Wessels, and McGurk and colleagues, have argued that since children are more obedient and malleable than adults, they are easier to control, deceive and indoctrinate.[8][9][2][10]

- David Gee and Rachel Taylor have found that in the UK, the army finds it easier to attract child recruits starting from age 16 than adults from age 18,[12] particularly those from poorer backgrounds.[51][52]

- Some leaders of armed groups have claimed that children, despite their underdevelopment, bring their own qualities as combatants to a fighting unit, often being remarkably fearless, agile and hardy.[53]

While some children are forcibly recruited, deceived, or bribed into joining military organisations, others join of their own volition.[11][54][2] There are many reasons for this. In a 2004 study of children in military organisations around the world, Rachel Brett and Irma Specht pointed to a complex of factors that incentivise enlisting, particularly:

- Background poverty including a lack of civilian education or employment opportunities

- The cultural normalization of war

- Seeking new friends

- Revenge (for example, after seeing friends and relatives killed)

- Expectations that a "warrior" role provides a rite of passage to maturity[11]

The following testimony from a child recruited by the Cambodian armed forces in the 1990s is typical of many children's motivations for joining up:

I joined because my parents lacked food and I had no school... I was worried about mines but what can we do—it's an order [to go to the front line]. Once somebody stepped on a mine in front of me—he was wounded and died... I was with the radio at the time, about 60 metres away. I was sitting in my hammock and saw him die... I see young children in every unit... I'm sure I'll be a soldier for at least a couple of more years. If I stop being a soldier I won't have a job to do because I don't have any skills. I don't know what I'll do...[55]

Impact on children

The scale of the impact on children was first acknowledged by the international community in a major report commissioned by the UN General Assembly, Impact of Armed Conflict on Children (1996), which was produced by the human rights expert Graça Machel.[14] The report was particularly concerned with the use of younger children, presenting evidence that many thousands of children were being killed, maimed, and psychiatrically injured around the world every year.[14]

Since the Machel Report further research has shown that child recruits who survive armed conflict face a markedly elevated risk of debilitating psychiatric illness, poor literacy and numeracy, and behavioural problems.[15] Research in Palestine and Uganda, for example, has found that more than half of former child soldiers showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and nearly nine in ten in Uganda screened positive for depressed mood.[15] Researchers in Palestine also found that children exposed to high levels of violence in armed conflict were substantially more likely than other children to exhibit aggression and anti-social behaviour.[15] The combined impact of these effects typically includes a high risk of poverty and lasting unemployment in adulthood.[15]

Further harm is caused when child recruits are detained by armed forces and groups, according to Human Rights Watch.[56] Children are often detained without sufficient food, medical care, or under other inhumane conditions, and some experience physical and sexual torture.[56] Some are captured with their families, or detained due to the activity of one of their family members. Lawyers and relatives are frequently banned from any court hearing.[56]

Other research has found that the enlistment of children, including older children, has a detrimental impact even when they are not used in armed conflict until they reach adulthood. Military academics in the US have characterized military training (at all ages) as "intense indoctrination" in conditions of sustained stress, the primary purpose of which is to establish the unconditional and immediate obedience of recruits.[10] The academic literature has found that adolescents are more vulnerable than adults to a high-stress environment, such as that of initial military training, particularly those from a background of childhood adversity.[57] Enlistment, even before recruits are sent to war, is accompanied by a higher risk of attempted suicide in the US,[16] higher risk of mental disorders in the US and the UK,[18][19] higher risk of alcohol misuse[20][21] and higher risk of violent behaviour,[22][23][24] relative to recruits' pre-enlistment background. Military settings are also characterised by elevated rates of bullying and sexual harassment.[58][59][60]

Military recruitment practices have also been found to exploit the vulnerabilities of children in mid-adolescence. Specifically, evidence from Germany,[61] the UK[62][63][12] and the US[64][65][66] has shown that recruiters disproportionately target children from poorer backgrounds using marketing that omits the risks and restrictions of military life. Some academics have argued that marketing of this kind capitalises on the psychological susceptibility in mid-adolescence to emotionally-driven decision-making.[67][68][69][57]

International law

Recruitment and use of children

Definition of child

The Convention on the Rights of the Child defines a child as any person under the age of 18. The Paris Principles define a child associated with an armed force or group as:

...any person below 18 years of age who is or who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys and girls, used as fighters, cooks, porters, messengers, spies or for sexual purposes. The document is approved by the United Nations General Assembly. It does not only refer to a child who is taking or has taken a direct part in hostilities.[70]

Children aged under 15

The Additional Protocols to the 1949 Geneva Conventions (1977, Art. 77.2),[71] the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (2002) all forbid state armed forces and non-state armed groups from using children under the age of 15 directly in armed conflict (technically "hostilities"). This is now recognised as a war crime.[72]

Children aged under 18

Most states with armed forces are also bound by the higher standards of the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (OPAC) (2000) and the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (1999), which forbid the compulsory recruitment of those under the age of 18.[33][73] OPAC also requires governments that still recruit children (from age 16) to "take all feasible measures to ensure that persons below the age of 18 do not take a direct part in hostilities". In addition, OPAC forbids non-state armed groups from recruiting children under any circumstances, although the legal force of this is uncertain.[74][27]

The highest standard in the world is set by the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child,[75] which forbids state armed forces from recruiting children under the age of 18 under any circumstances. Most African states have ratified the Charter.[75]

Limitations and loopholes

States that are not a party to OPAC are subject to the lower standards set by Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions, which allows armed forces to use children over the age of fifteen in hostilities, and possibly to use younger children who have volunteered as spotters, observers, and message-carriers:[76]

The Parties to the conflict shall take all feasible measures so that children who have not attained the age of fifteen years do not take a direct part in hostilities and, in particular, they shall refrain from recruiting them into their armed forces. In recruiting among those persons who have attained the age of fifteen years but who have not attained the age of eighteen years, the Parties to the conflict shall endeavor to give priority to those who are oldest.

The International Committee of the Red Cross had proposed that the Parties to the conflict should "take all necessary measures", which became in the final text, "take all feasible measures", which is not a total prohibition because feasible is understood as meaning "capable of being done, accomplished or carried out, possible or practicable".[76] During the negotiations over the clause "take a part in hostilities" the word "direct" was added to it, opening up the possibility that child volunteers could be involved indirectly in hostilities, such as by gathering and transmitting military information, helping in the transportation of arms and munitions, provision of supplies, etc.[76]

However, Article 4.3.c of Protocol II, additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts, adopted in 1977, states "children who have not attained the age of fifteen years shall neither be recruited in the armed forces or groups nor allowed to take part in hostilities".[77]

Standards for the release and reintegration of children

OPAC requires governments to demobilise children within their jurisdiction who have been recruited or used in hostilities and to provide assistance for their physical and psychological recovery and social reintegration.[78] Under war, civil unrest, armed conflict and other emergency situations, children and youths are also offered protection under the United Nations Declaration on the Protection of Women and Children in Emergency and Armed Conflict. To accommodate the proper disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration of former members of armed groups, the United Nations started the Integrated DDR Standards in 2006.[79]

War crimes

Opinion is currently divided over whether children should be prosecuted for war crimes.[80] International law does not prohibit the prosecution of children who commit war crimes, but Article 37 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child limits the punishment that a child can receive: "Neither capital punishment nor life imprisonment without possibility of release shall be imposed for offenses committed by persons below eighteen years of age."[80]

Example: Sierra Leone

In the wake of the Sierra Leone Civil War, the UN mandated the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) to try former combatants aged 15 and older for breaches of humanitarian law, including war crimes. However, the Paris Principles state that children who participate in armed conflict should be regarded first as victims, even if they may also be perpetrators:

... [those] who are accused of crimes under international law allegedly committed while they were associated with armed forces or armed groups should be considered primarily as victims of offenses against international law; not only as perpetrators. They must be treated by international law in a framework of restorative justice and social rehabilitation, consistent with international law which offers children special protection through numerous agreements and principles.[81]

This principle was reflected in the Court's statute, which did not rule out prosecution but emphasised the need to rehabilitate and reintegrate former child soldiers. David Crane, the first Chief Prosecutor of the Sierra Leone tribunal, interpreted the statute in favour of prosecuting those who had recruited children, rather than the children themselves, no matter how heinous the crimes they had committed.[80]

Example: Omar Khadr

In the US, prosecutors charged Omar Khadr, a Canadian, for offences they allege he committed in Afghanistan while under the age of 16 and fighting for the Taliban against US forces.[82] These crimes carry a maximum penalty of life imprisonment under US law.[80] In 2010, while under torture and duress, Khadr pleaded guilty to murder in violation of the laws of war, attempted murder in violation of the laws of war, conspiracy, two counts of providing material support for terrorism, and spying.[83][84] The plea was offered as part of a plea bargain, which would see Khadr deported to Canada after one year of imprisonment to serve seven further years there.[85] Omar Khadr remained in Guantanamo Bay and the Canadian government faced international criticism for delaying his repatriation.[86] Khadr was eventually transferred to the Canadian prison system in September 2012 and was freed on bail by a judge in Alberta in May 2015. As of 2016, Khadr was appealing his US conviction as a war criminal.[87]

Before sentencing the Special Representative to the UN Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict wrote to the US military commission at Guantanamo appealing unsuccessfully for Khadr's release into a rehabilitation program.[88] In her letter she said that Khadr represented the "classic child soldier narrative: recruited by unscrupulous groups to undertake actions at the bidding of adults to fight battles they barely understand".[88]

The role of the United Nations

Background

Children's rights advocates were left frustrated after the final text of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) did not prohibit the military recruitment of all children under the age of 18, and they began to call for a new treaty to achieve this goal.[32][89] As a consequence the newly formed Committee on the Rights of the Child made two recommendations: first, to request a major UN study into the impact of armed conflict on children; and second, to establish a working group of the UN Commission on Human Rights to negotiate a supplementary protocol to the Convention.[89] Both proposals were accepted.[32][89]

Responding to the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the UN General Assembly acknowledged "the grievous deterioration in the situation of children in many parts of the world as a result of armed conflicts" and commissioned the human rights expert Graça Machel to conduct a major fact-finding study.[90] The Machel Report, Impact of armed conflict on children, was published in 1996.[14] The report noted:

Clearly one of the most urgent priorities is to remove everyone under 18 years of age from armed forces.[14]

Meanwhile, the UN Commission on Human Rights established a working group to negotiate a treaty to raise standards with regard to the use of children for military purposes.[32][89] After complex negotiations and a global campaign, the new treaty was agreed in 2000 as the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict.[32] The treaty prohibits the direct participation of children in armed conflict, but not their recruitment by state armed forces from age 16.[91]

The UN has identified 14 countries where children have been widely used as soldiers. These countries are Afghanistan, Colombia, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Mali, Myanmar, Nigeria, the Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. The use of child soldiers spans the globe. In an article for the Middle East Institute, the authors Mick Mulroy, Zack Baddorf and Eric Oehlerich, all former military and special operations, state that this issue of child soldiers happens in many locations where the world's superpowers have deployed their own military forces. Therefore, "those superpowers have a responsibility to help end this practice of child exploitation".[92]

Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict

The Machel Report led to a new mandate for a Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict (SRSG-CAAC).[90] Among the tasks of the SRSG is to draft the Secretary-General's annual report on children and armed conflict, which lists and describes the worst situations of child recruitment and use from around the world.[93]

Security Council

The United Nations Security Council convenes regularly to debate, receive reports, and pass resolutions under the heading "Children in armed conflict". The first resolution on the issue, Resolution 1261, was passed in 1999.[94] In 2004 Resolution 1539 was passed unanimously, condemning the use of child soldiers and mandating the UN Secretary-General to establish a means of tracking and reporting on the practice, known as the Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism.[95][96]

United Nations Secretary-General

The Secretary-General publishes an annual report on children and armed conflict.[97] The 2017 report identified 14 countries where children were widely used by armed groups during 2016 (Afghanistan, Colombia, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Mali, Myanmar, Nigeria, Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen) and six countries where state armed forces were using children in hostilities (Afghanistan, Myanmar, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, and Syria).[28]

In 2011 United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon raised the issue of children in conflict areas who are involved in violent activities according to the Extreme Measures report.[98]

Children in the military today—by region and country

This section covers the use of children for military purposes today. For historical cases, see History of children in the military.

Africa

In 2003, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated that up to half of children involved with state armed forces and non-state armed groups worldwide were in Africa.[46] In 2004, Child Soldiers International estimated that 100,000 children were being used in state and non-state armed forces on the continent;[99] and in 2008 an estimate put the total at 120,000 children, or 40 percent of the global total.[100]

The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (1990), which has been ratified by most African states, prohibits all military recruitment of children aged under 18. Nonetheless, according to the UN, in 2016 children were being used by armed groups in seven African countries (Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan) and by state armed forces in three (Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan).[28]

International efforts to reduce the number of children in military organisations in Africa began with the Cape Town Principles and Best Practices, developed in 1997.[101] The Principles proposed that African governments commit to OPAC, which was being negotiated at the time, and raise the minimum age for military recruitment from 15 to 18.[101] The Principles also defined a child soldier to include any person under the age of 18 who is "part of any kind of regular or irregular armed force or group in any capacity ... including girls recruited for sexual purposes ..."[101]

In 2007, the Free Children from War conference in Paris produced the Paris Principles, which refined and updated the Cape Town Principles, applied them globally, and outlined a practical approach to reintegrating current child soldiers.[102]

Central African Republic

The use of children by armed groups in the Central African Republic has historically been common.[99] Between 2012 and 2015 as many as 10,000 children were used by armed groups in the nationwide armed conflict and as of 2016 children were still being used.[103][28] The mainly Muslim Séléka coalition of armed groups and the predominantly Christian Anti-balaka militias have both used children in this way; some are as young as eight.[104]

In May 2015 at the Forum de Bangui (a meeting of government, parliament, armed groups, civil society, and religious leaders), a number of armed groups agreed to demobilize thousands of children.[105]

In 2016 a measure of stability returned to the Central African Republic and, according to the United Nations, 2,691 boys and 1,206 girls were officially separated from armed groups.[28] Despite this, the recruitment and use of children for military purposes increased by approximately 50 percent over that year, mostly attributed to the Lord's Resistance Army.[28]

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Thousands of children serve in the military of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), as well as in various rebel militias. It has been estimated that at the height of the Second Congo War more than 30,000 children were fighting with various parties to the conflict. It was claimed in the film Kony 2012 that the Lord's Resistance Army recruited this number.[106]

Currently the DRC has one of the highest proportions of child soldiers in the world. The international court has passed judgment on these practices during the war. Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, one of the warlords in the DRC, has been sentenced to 14 years in prison because of his role in the recruitment of child soldiers between 2002 and 2003. Lubanga directed the Union of Congolese Patriots and its armed wing Patriotic Forces for the Liberation of Congo. The children were forced to fight in the armed conflict in Ituri.[107]

Somalia

A report published by the Child Soldiers International in 2004 estimated that 200,000 children had been recruited into the country's militias against their will since 1991.[99] In 2017 UN Secretary-General António Guterres commented on a UN report which estimated that over 50 percent of Al-Shabaab's membership in the country was under the age of 18, with some as young as nine being sent to fight.[108] The report verified that 6,163 children had been recruited in Somalia between 1 April 2010 and 31 July 2016, of which 230 were girls. Al-Shabaab accounted for seventy percent of this recruitment, and the Somali National Army was also recruiting children.[108][109]

Sudan

In 2004 approximately 17,000 children were being used by the state armed forces and non-state armed groups.[110] As many as 5,000 children were part of the main armed opposite group at the time, the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA).[110] Some former child soldiers were sentenced to death for crimes committed while they were soldiers.[99]

In 2006, children were also recruited from refugee camps in Chad, and thousands were used in the conflict in Darfur.[111] In 2005 the government ratified the OPAC treaty and by 2008 the military use of children had reduced in the country, but both state armed forces and the SPLA continued to recruit and use them.[111] The use of children has continued to diminish, but in 2017 the UN was still receiving reports of children as young as 12 in government forces.[112][113]

Zimbabwe

In 2003, the Guardian reported multiple human rights violations by the National Youth Service, a state-sponsored youth militia in Zimbabwe.[114] Originally conceived as a patriotic youth organisation, it became a paramilitary group of youth aged between 10 and 30, and was used to suppress dissent in the country.[115] The organisation was finally banned in January 2018.[116]

Americas

Bolivia

In 2001 the government of Bolivia acknowledged that children as young as 14 May have been forcibly conscripted into the armed forces during recruitment sweeps.[117] About 40% of the Bolivian army was believed to be under the age of 18, with half of those below the age of 16.[117] As of 2018, Bolivia invites children to begin their adult conscription early, from age 17.[118]

Canada

In Canada, people may join the reserve component of the Canadian Forces at age 16 with parental permission, and the regular component at 17 years of age, also with parental permission. They may not volunteer for a tour of duty until reaching age 18.[119]

Colombia

In the Colombian armed conflict, from the mid-1960s to present, one fourth of non-state combatants have been and still are under 18 years old. In 2004 Colombia ranked fourth in the world for the greatest use of child soldiers. There are currently 11,000–14,000 children in armed groups in the country. In negotiations with the government, armed groups have offered to stop the recruitment of minors as a bargaining chip, but they have not honoured these offers.[120][121] Bjørkhaug argues that most child soldiers were recruited through some combination of voluntary participation and coercion.[122]

In 1998 a Human Rights Watch press release indicated that 30 percent of some guerrilla units were made up of children and up to 85 percent of some of the militias, which are considered to serve as a "training ground for future guerrilla fighters", had child soldiers[123] In the same press release it was estimated that some of the government-linked paramilitary units consisted of up to 50 percent children, including some as young as 8 years old.[124][123]

In 2005 an estimated 11,000 children were involved with left- or right-wing paramilitaries in Colombia. "Approximately 80 percent of child combatants in Colombia belong to one of the two left-wing guerrilla groups, the FARC or ELN. The remainder fight in paramilitary ranks, predominately the AUC."[125] According to P. W. Singer the FARC attack on the Guatape hydroelectric facility in 1998 involved militants as young as eight years old and a 2001 FARC training video depicted boys as young as 11 working with missiles. The group has also taken in children from Venezuela, Panama, and Ecuador.[124]

The Colombian government's security forces do not officially recruit children[126] as the legal age for both compulsory and voluntary recruitment has been set at 18. However, students were allowed to enroll as cadets in military secondary schools and 16- or 17-year-olds could enter air force or national army training programs, respectively. In addition, captured enemy child combatants were employed by the Colombian military for intelligence gathering purposes in potential violation of legal prohibitions.[127]

The demobilisation efforts targeted toward the FARC in 2016–2017 have provided hope that the conflict will come to an end, limiting the number of children involved in violence. However, other armed groups have yet to be demobilised, and conflict is not yet resolved.[128]

Cuba

In Cuba compulsory military service for both boys and girls starts at age 17. Male teenagers are allowed to join the Territorial Troops Militia prior to their compulsory service.[129]

Haiti

In Haiti an unknown number of children participate in various loosely organised armed groups that are engaged in political violence.[130]

United States

In the United States 17-year-olds may join the armed forces with the written agreement of parents.[131] As of 2015 approximately 16,000 17-year-olds were being enlisted annually.[132]

The US army describes outreach to schools as the 'cornerstone' of its approach to recruitment,[133] and the No Child Left Behind Act gives recruiters the legal right of access to all school students' contact details.[134] Children's rights bodies have criticised the US' reliance on children to staff its armed forces.[135][136][137] The Committee on the Rights of the Child has recommended that the US raise the minimum age of enlistment to 18.[135]

In negotiations on the OPAC treaty during the 1990s the US joined the UK in strongly opposing a global minimum enlistment age of 18, and as a consequence the treaty specified a minimum age of 16.[32] The US ratified the treaty in 2002 (but as of 2018 has not ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child itself).[138]

Per OPAC, US military personnel are normally prohibited from direct participation in hostilities until the age of 18, but they are eligible for 'forward deployment', which means that may be posted to a combat zone to perform support tasks.[139] The Committee on the Rights of the Child has called on the US to change this policy and ensure that no minor can be deployed to a forward operating area in a combat zone.[140]

In 2003 and 2004 approximately 60 underage personnel were deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq in error.[136] The Department of Defense subsequently stated that "the situations were immediately rectified and action taken to prevent recurrence."[141]

In 2008 President George W. Bush signed the Child Soldiers Protection Act into law.[142][143] The law criminalises leading a military force which recruits child soldiers. It also prohibits arms sales to countries where children are used for military purposes. The law's definition of child soldiers includes "any person under 18 years of age who takes a direct part in hostilities as a member of governmental armed forces." In 2014 President Barack Obama announced he was waiving the Child Soldiers Protection Act ban on aid and arms sales to nations that use child soldiers.[144]

Middle East

The UN Office for Children and Armed Conflict found that the number of children either forcibly or voluntarily fighting in the various conflicts in the Middle East and Africa doubled in number in 2019.[145] In an article for the Middle East Institute, the former deputy secretary of defense for the Middle East, Michael Mulroy, said that this is not a new trend and "that this should shock and alarm the international community. The growth has come in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen — all Middle Eastern countries embroiled in intense conflict with no peace in sight."[146]

Bahrain

Military cadets, NCO trainees and technical personnel can enlist in the Bahrain Defence Force from the age of 15.[147]

Iran

Current Iranian law officially prohibits the recruitment of those under 16.[148][124]

During the Iran–Iraq War, children were drafted into the Basij army where, according to critics of the Iranian government, they "were sent to the front as waves of human shields".[149][150] Other sources have estimated the total number of all Iranian casualties to be in the 200,000–600,000 range.[151][152][153][154][155][156][157][158][159][148] One source estimates that 3% of the Iran–Iraq War's casualties were under the age of 14.[160]

There were Iranian children who left school and participated in the Iran–Iraq War without the knowledge of their parents, including Mohammad Hossein Fahmideh. Iraqi officers claimed that they sometimes captured Iranian child soldiers as young as eight years old.[161]

As of 2018 the Iranian government has been recruiting children from Iran and Afghanistan to fight in the Syrian Civil War on the side of forces loyal to the Assad government.[162][163]

Israel and Palestine

Jihad Shomaly, in a report entitled Use of Children in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, published in 2004 for the Defence for Children International/Palestine Section, concludes the report by stating that a handful of children perceive martyrdom a way to strike a blow against those they hold responsible for their hopeless situation, and that they have been recruited by Palestinian paramilitary groups to carry out armed attacks. However, Shomaly goes on to state that there is no systematic recruitment and that senior representatives of the groups and of the Palestinian community are against the recruitment of children as a political strategy. Shomaly gave the opinion that the political leadership of the Palestinians could do more to discourage the use of children by paramilitaries by requesting that the leadership of the paramilitaries sign a memorandum forbidding the training and recruitment of children. Hamas, the Palestinian organisation governing the Gaza strip, has been known to indoctrinate child soldiers with controversial ideologies, such as inciting violence against Israeli occupation forces.[164]

William O'Brien, a professor of Georgetown University, wrote about the active participation of Palestinian children in the First Intifada: "It appears that a substantial number, if not the majority, of troops of the intifada are young people, including elementary schoolchildren. They are engaged in throwing stones and molotov cocktails and other forms of violence."[165] Arab journalist Huda Al-Hussein wrote in a London Arab newspaper on 27 October 2000:

While UN organizations save child-soldiers, especially in Africa, from the control of militia leaders who hurl them into the furnace of gang-fighting, some Palestinian leaders... consciously issue orders for the purpose of ending their childhood, even if it means their last breath.[166]

In 2002 the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers (now Child Soldiers International) said that, "while there are reports of children participating in hostilities, there is no evidence of systematic recruitment by armed groups".[167][168] In 2004, however, the organisation reported that there were at least nine documented suicide attacks involving Palestinian minors between October 2000 and March 2004,[31] stating:

There was no evidence of systematic recruitment of children by Palestinian armed groups. However, children are used as messengers and couriers, and in some cases as fighters and suicide bombers in attacks on Israeli soldiers and civilians. All the main political groups involve children in this way, including Fatah, Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.[169]

In May 2008 a Child Soldiers International report highlighted Hamas and Islamic Jihad for having "used children in military attacks and training" in its Iranian section.[148]

On 23 May 2005 Amnesty International reiterated its calls to Palestinian armed groups to put an immediate end to the use of children in armed activities: "Palestinian armed groups must not use children under any circumstances to carry out armed attacks or to transport weapons or other material."[170]

Turkey (PKK)

During the Kurdish-Turkish conflict, the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) has actively recruited and kidnapped children. The organization has been accused of abducting more than 2,000 children by Turkish Security Forces. The independent reports by the Human Rights Watch (HRW), the United Nations (UN) and the Amnesty International have confirmed the recruitment and use of child soldiers by the organization and its armed wings since the 90's.[171][172][173][174] In 2001, it was reported that the recruitment of the children by the organization has been systematic. Several reports have reported about the organization's battalion, called Tabura Zaroken Sehit Agit, which has been formed mainly for the recruitment of children.[175] It was also reported that the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) had recruited children.[176]

According to the Turkish Security Forces, the PKK has abducted more than 983 children aged between 12 and 17, and more than 400 children have fled from the organization and surrendered to the security forces. The United Nations Children's Fund report, published in 2010, saw the recruitment of the children by the PKK concerning and dangerous.[177]

In 2016, the Human Rights Watch, accused the PKK of committing war crimes by recruiting child soldiers in the Shingal region of Iraq and in neighboring countries.[172][178]

Throughout the Syrian Civil War multiple media outlets including Human Rights Watch have confirmed that the YPG, an organization linked to the PKK, has been recruiting and deploying child soldiers. Despite a claim by the group that it would stop using children, which has been violation of international law, the group has continued the recruitment and use of children.[179][180][181]

In 2018, the annual UN report on children in armed conflict found 224 cases of child recruitment by the People's Protection Units and its women's unit in 2017, an almost fivefold increase from the 2016. Seventy-two of the children, nearly one-third, were girls. The group was also reported to had abducted children to enlist them.[182]

Lebanon

Many different sides in the Lebanese Civil War used child soldiers. A May 2008 Child Soldiers International report stated that Hezbollah trains children for military services.[148] In 2017, the UN reported that armed groups, suspected to be Islamist militants, were recruiting children in the country.[28]

Syria

During the ongoing Syrian Civil War children have joined groups opposed to Bashar al Assad. In 2012 the UN received allegations of rebels using child soldiers, but said they were unable to verify these.[183] In June 2014 a United Nations report said that the opposition had recruited children in military and support roles. While there seemed to be no policy of doing so, the report said, there were no age verification procedures.[184] Human Rights Watch reported in 2014 that rebel factions have been using children in support and combatant roles, ranging from treating the wounded on battlefields, ferrying ammunition and other supplies to frontlines while fighting raged, to acting as snipers.[185]

Kurdish forces have also been accused of using this tactic. In 2015 Human Rights Watch claimed that 59 children, 10 of them under 15 years old, were recruited by or volunteered for the YPG or YPJ since July 2014 when the Kurdish militia leaders signed a Deed of Commitment with Geneva Call.[186]

President Assad passed a law in 2013 prohibiting the use of child soldiers (anyone under 18), the breaking of which is punishable by 10–20 years of 'penal labour.'[187] Whether or not the law is actually enforced on government's forces has not been confirmed, and there have been allegations of children being recruited to fight for the Syrian government against rebel forces.[188][185]

Iranian government is recruiting children from Iran and Afghanistan to fight in the Syrian Civil War on the side of Assad's regime's forces.[162][163]

Yemen

U.N. Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict Radhika Coomaraswamy stated in January 2010 that "large numbers" of teenage boys are being recruited in Yemeni tribal fighting. NGO activist Abdul-Rahman al-Marwani has estimated that as many as 500–600 children are either killed or wounded through tribal combat every year in Yemen.[189]

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates hired child soldiers from Sudan (especially from Darfur), and Yemen to fight against Houthis during the Yemeni Civil War (2015–present).[39][40][41]

British SAS special forces are allegedly involved in training child soldiers in Yemen. Reportedly at least 40% of soldiers fighting for the Saudi-led coalition are children.[190]

Saudi Arabia is also hiring Yemeni child soldiers to guard Saudi border against Houthis.[191]

Asia

.jpg)

In 2004 the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers (now Child Soldiers International) reported that in Asia thousands of children are involved in fighting forces in active conflict and ceasefire situations in Afghanistan, Burma, Indonesia, Laos, Philippines, Nepal and Sri Lanka. Government refusal of access to conflict zones has made it impossible to document the numbers involved.[192] In 2004 Burma was unique in the region as the only country where government armed forces forcibly recruited and used children between the ages of 12 and 16.[192] Johnny and Luther Htoo, twin brothers who jointly led the God's Army guerrilla group, were estimated to have been around ten years old when they began leading the group in 1997.[193]

Afghanistan

Militias recruited thousands of child soldiers during the Afghan civil war over three decades. Many are still fighting now, for the Taliban. Some of those taken from Islamic religious schools, or madrassas, are used as suicide bombers and gunmen. A propaganda video of boys marching in camouflage uniform and using slogans of martyrdom was issued in 2009 by the Afghan Taliban's leadership. This included a eulogy to a 14-year-old Taliban fighter who allegedly killed an American soldier.[194]

Burma/Myanmar

The State Peace and Development Council has asserted that all of its soldiers volunteered and that all of those accepted are 18 or over. According to Human Rights Watch as many as 70,000 boys serve in Burma/Myanmar's national army, the Tatmadaw, with children as young as 11 being forcibly recruited off the streets. Desertion, the group reported, leads to punishments of three to five years in prison or even execution. The group has also stated that about 5,000–7,000 children serve with a range of different armed ethnic opposition groups, most notably in the United Wa State Army.[195] UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon released a report in June 2009 mentioning "grave violations" against children in the country by both the rebels and the government. The administration announced on 4 August that they would send a team into Burma/Myanmar to press for more action.[196]

India

In India volunteers can join the Navy from the age of 16 and a half, and the Air Force from the age of 17. These soldiers are not deployed until after training by which time they are 18 years or older.[197]

Nepal

An estimated 6,000–9,000 children serve in the Communist Party of Nepal forces. As of 2010, child soldiers of the CPN has since been demobilized[198]

The Philippines

Islamist and communist armed groups fighting the government have routinely relied on child recruits.[199] In 2001 Human Rights Watch reported that an estimated 13 percent of the 10,000 soldiers in the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) were children, and that some paramilitary forces linked to the government were also using children.[200] In 2016 the MILF allowed 1,869 children to leave and committed not to recruit children any more.[28] In the same year, however, the UN reported that other armed groups in the Philippines continue to recruit children, mainly between the ages of 13 and 17.[28]

Europe

According to Child Soldiers International the trend in Europe has been towards recruiting only adults from age 18;[25] most states only allow adult recruitment,[12] and as of 2016 no armed groups were known to be using children.[38] As of 2018 one country, the United Kingdom, was enlisting children from age 16, and five were enlisting from age 17 (Austria, Cyprus, France, Germany, and Netherlands).[34] Of these, the UK recruits children in the greatest numbers; in 2016, approximately a quarter of new recruits to the British army were aged under 18.[12]

All European states have ratified the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict,[201] and so child recruits are not typically used in hostilities until they reach adulthood.[91] Children were used as combatants in the First Chechen War during the 1990s.[202]

Austria

Austria invites children to begin their adult compulsory military service one year early, at age 17, with the consent of their parents.[203]

Cyprus

Cyprus invites children to begin their adult compulsory military service two years early, at age 16, with the consent of their parents.[204]

France

France enlists military personnel from age 17, and students for military technical school from age 16; 3% of its armed forces' intake is aged under 18.[205]

Germany

Germany enlists military personnel from age 17; in 2015 6% of its armed forces' intake was aged under 18.[206]

Netherlands

The Netherlands enlists military personnel from age 17; in 2014 5% of its armed forces' intake was aged under 18.[207]

Ukraine

During the armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine in 2014 Justice for Peace at Donbas documented 41 verified individual cases of child recruitment into armed formations.[208] Of those 37 concerned the participation of children in armed formations on territory not controlled by Ukraine and 4 on territory controlled by Ukraine. There were 31 further reports of child recruitment which could not be verified. Of the 37 verified cases on territory not controlled by Ukraine, 33 were boys and 4 were girls; 57% were aged 16–17, 35% were under 15, and age could not be determined in 8% of cases.[208]

United Kingdom

The British armed forces enlist from age 16 and accept applications from children aged 15 years, 7 months.[209] As of 2016 approximately one-quarter of enlistees to the British army were aged under 18.[12] As per the OPAC the UK does not routinely send child recruits to participate in hostilities, and it requires recruiters to seek parental consent prior to enlistment.[210] Children's rights bodies have criticised the UK's reliance on children to staff its armed forces.[211][212][213][12]

Although the UK normally prohibits deployment to war zones until recruits turn 18, it does not rule out doing so.[201] It inadvertently deployed 22 personnel aged under 18 to Iraq and Afghanistan between 2003 and 2010.[214] The Committee on the Rights of the Child has urged the UK to alter its policy so as to ensure that children cannot take part in hostilities under any circumstances.[215] In negotiations on the OPAC during the 1990s the UK joined the US in opposing a global minimum enlistment age of 18.[32]

In 2014, a group of 17-year-old army recruits alleged that 17 instructors had maltreated them during their training over nine days in June 2014.[216][217][218] It was reported as the British army's largest ever investigation of abuse.[216][219] Among the allegations were that the instructors assaulted recruits, smeared cattle dung into their mouths, and held their heads under water.[217][216][219] The court martial began in 2018,[218] but soon collapsed after the judge ruled that the Royal Military Police (RMP) had abused the investigatory process and that a fair trial would therefore not be possible.[220]

Oceania

Australia

The Australian Defence Force allows personnel to enlist with parental consent from the age of 17. Personnel under the age of 18 cannot be deployed overseas or used in direct combat except in extreme circumstances where it is not possible to evacuate them.[221]

New Zealand

As of 2018, the minimum age for joining the New Zealand Defence Force was 17.[222]

Movement to end military use of children

The military use of children has been common throughout history; only in recent decades has the practice met with informed criticism and concerted efforts to end it.[223] Progress has been slow, partly because many armed forces have relied on children to fill their ranks,[25][26][32] and partly because the behaviour of non-state armed groups is difficult to influence.[27]

Recent history

1970s–1980s

International efforts to limit the participation of children in armed conflict began with the Additional Protocols to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, adopted in 1977 (Art. 77.2).[71] The new Protocols prohibited the military recruitment of children aged under 15, but continued to allow state armed forces and non-state armed groups to recruit children from age 15 and use them in warfare.[76][32]

Efforts were renewed during negotiations on the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), when Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) campaigned for the new treaty to outlaw child recruitment entirely.[32] Some states, whose armed forces relied on recruiting below the age of 18, resisted this, so the final treaty text of 1989 only reflected the existing legal standard: the prohibition of the direct participation of children aged under 15 in hostilities.[32]

1990s

In the 1990s NGOs established the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers (now Child Soldiers International) to work with sympathetic governments on a campaign for a new treaty to correct the deficiencies they saw in the CRC.[32] After a global campaign lasting six years, the treaty was adopted in 2000 as the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (OPAC). The treaty prohibits child conscription, ensures that military recruits are no younger than 16, and forbids the use of child recruits in hostilities. The treaty also forbids non-state armed groups from recruiting anyone under the age of 18 for any purpose.[91] Although most states negotiating OPAC supported a ban on recruiting children, some states, led by the US in alliance with the UK, objected to this.[32][89] As such, the treaty does not ban the recruitment of children aged 16 or 17, although it allows states to bind themselves to a higher standard in law.[91]

2000s-present

After the adoption of the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, a campaign for global ratification made swift progress.[32] As of 2018 OPAC had been ratified by 167 states.[201] The campaign also successfully encouraged many states not to recruit children at all. In 2001 83 states only allowed adult enlistment, by 2016 this had increased to 126, which is 71 percent of countries with armed forces.[25] Approximately 60 non-state armed groups have also entered agreements to stop or scale back their use of children, often brokered by the UN or the NGO Geneva Call.[27]

Child Soldiers International reports that the success of the OPAC treaty, combined with the gradual decline in child recruitment by state armed forces, has led to a reduction of children in military organisations worldwide.[25] As of 2018 the recruitment and use of children remains widespread. In particular, militant Islamist organisations such as ISIS and Boko Haram, as well as armed groups fighting them, have used children extensively.[38] In addition, the three most populous states – China, India and the United States – still allow their armed forces to enlist children aged 16 or 17, as do five of the Group of Seven countries: Canada, France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States, again.[25]

Events

Red Hand Day (also known as the International Day Against the Use of Child Soldiers) on 12 February is an annual commemoration day to draw public attention to the practice of using children as soldiers in wars and armed conflicts. The date reflects the entry into force of the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict.[91]

Countering the militarisation of childhood

Many states which do not allow their armed forces to recruit children have continued to draw criticism for marketing military life to children through the education system, in civic spaces and in popular entertainment such as films and videogames.[224] Some commentators have argued that this marketing to children is manipulative and part of a military recruitment process and should therefore be evaluated ethically as such.[63][225] This principle has led some groups to campaign for relations between military organisations and young people to be regulated, on the grounds of children's rights and public health.[64][226] Examples are the Countering the Militarization of Youth programme of War Resisters' International,[227] the Stop Recruiting Kids campaign in the US,[228] and the Military Out of Schools campaign in the UK.[226] Similar concerns have been raised in Germany and Israel.[61][229]

Rehabilitation and reintegration of child soldiers

Child Soldiers International defines reintegration as: "The process through which children formerly associated with armed forces/groups are supported to return to civilian life and play a valued role in their families and communities"[230] Programs that aim to rehabilitate and reintegrate child soldiers, such as those sponsored by UNICEF, often emphasise three components: family reunification/community network, psychological support, and education/economic opportunity.[3][231] These efforts take a minimum commitment of 3 to 5 years in order for programs to be successfully implemented.[3][231] Generally, reintegration efforts seek to return children to a safe environment, to create a sense of forgiveness on the behalf of the child's family and community through religious and cultural ceremonies and rituals, and encourage the reunification of the child with his or her family.[3][231]

Reintegration efforts can become challenging when the child in question has committed war crimes because in these cases stigma and resentment within the community can be exacerbated. In situations such as these, it is important that the child's needs are balanced with a sense of community justice.[3][231] These situations should be addressed immediately because if not, many children face the threat of re-enlistment.[230] There are also two areas of reintegration that warrant special consideration: female child soldiers and drug use among child soldiers.[4][231] Child soldiers under the influence of drugs or who have contracted sexually transmitted diseases require additional programmes specific to their needs.[3][231]

See also

General

Well-known cases of children used for military purposes

- Grace Akallo, Ugandan

- Loung Ung, Cambodian

- Ishmael Beah, Sierra Leonean

- Calvin Graham, American

- Himeyuri students, Japanese

- Mohammad Hossein Fahmideh, Iranian

- Omar Khadr, Canadian

- Luftwaffenhelfer, German

- Lwów Eaglets, Polish

- Dominic Ongwen, Ugandan

- Returned: Child Soldiers of Nepal's Maoist Army

Campaigns and campaigners to end the use of children in the military

- Child Soldiers International

- Els de Temmerman

- Graça Machel

- Romeo Dallaire

- War Resisters International (Countering Militarization of Youth programme)

- Red Hand Day

Related crimes against children

Related international law and standards

- Convention on the Rights of the Child

- Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

- Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention

- International humanitarian law

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1998

- Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict

- Paris Principles (Free Children from War Conference)

Other minority groups in the military

Documentary film

- Kony 2012, documentary film

- "La vita non perde valore" ("Life does not lose its value"), documentary film

- "My Star in the Sky" a true story of survival, friendship and love between two child soldiers abducted by the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) during the conflict between Uganda and Sudan.[232][233]

Popular culture

- Beasts of No Nation, movie

- Blood Diamond, movie

- Johnny Mad Dog, movie

Further reading

- Vautravers, A. J. (2009). Why Child Soldiers are Such a Complex Issue. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 27(4), 96–107. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdp002

- Humphreys, Jessica Dee (2015). Child Soldier: When Boys and Girls Are Used in War. Toronto: Kids Can Press ISBN 978-1-77138-126-0

- International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT) & The Global Center on Cooperative Security (September 2017). "Correcting the Course: Juvenile Justice Principles for Children Convicted of Violent Extremism Offenses", ICCT & GCCS, 1–12. Correcting the Course: Advancing Juvenile Justice Principles for Children Convicted of Violent Extremist Offenses

- Dr U C Jha (2018), "Child Soldiers – Practice, Law and Remedies". Vij Books India Pvt Ltd ISBN 9789386457523

References

- UNICEF (2007). "The Paris Principles: Principles and guidelines on children associated with armed forces or armed groups" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Wessels, Michael (1997). "Child Soldiers". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 53 (4): 32. Bibcode:1997BuAtS..53f..32W. doi:10.1080/00963402.1997.11456787.

- "How did Britain let 250000 underage soldiers fight in WW1?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- Norman Davies, Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw, Archived 6 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine Pan Books 2004 p.603

- David M. Rosen (January 2005). Armies of the Young: Child Soldiers in War and Terrorism. Rutgers University Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-8135-3568-5. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

The participation of Jewish children and youth in warfare was driven by a combination of necessity, honor, and moral duty.

- Kucherenko, Olga (13 January 2011). Little Soldiers: How Soviet Children Went to War, 1941–1945. OUP Oxford. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-161099-8. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- "Children at war". History Extra. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Beber, Blattman, Bernd, Christopher (2013). "The Logic of Child Soldiering and Coercion". International Organization. 67 (1): 65–104. doi:10.1017/s0020818312000409.

- Dave., Grossman (2009). On killing : the psychological cost of learning to kill in war and society (Rev. ed.). New York: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 9780316040938. OCLC 427757599.

- McGurk, Dennis; Cotting, Dave I.; Britt, Thomas W.; Adler, Amy B. (2006). "Joining the ranks: The role of indoctrination in transforming civilians to service members". In Adler, Amy B.; Castro, Carl Andrew; Britt, Thomas W. (eds.). Military life: The psychology of serving in peace and combat. volume 2: Operational stress. Westport: Praeger Security International. pp. 13–31. ISBN 978-0275983024.

- Brett, R; Specht, I (2004). Young soldiers : why they choose to fight. Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 9781588262615. OCLC 53830868.

- Gee, David; Taylor, Rachel (1 November 2016). "Is it Counterproductive to Enlist Minors into the Army?". The RUSI Journal. 161 (6): 36–48. doi:10.1080/03071847.2016.1265837. ISSN 0307-1847.

- Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers (2008). "Child Soldiers Global Report 2008". Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Machel, G (1996). "Impact of armed conflict on children" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Boothby, N; et al. (2010). "Child soldiering: Impact on childhood development and learning capacity". Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Ursano, Robert J.; Kessler, Ronald C.; Stein, Murray B.; Naifeh, James A.; Aliaga, Pablo A.; Fullerton, Carol S.; Wynn, Gary H.; Vegella, Patti L.; Ng, Tsz Hin Hinz (1 July 2016). "Risk Factors, Methods, and Timing of Suicide Attempts Among US Army Soldiers". JAMA Psychiatry. 73 (7): 741–9. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0600. ISSN 2168-622X. PMC 4937827. PMID 27224848.

- UK, Ministry of Defence (2017). "UK armed forces suicide and open verdict deaths: 1984–2017". Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Goodwin, L.; Wessely, S.; Hotopf, M.; Jones, M.; Greenberg, N.; Rona, R. J.; Hull, L.; Fear, N. T. (2015). "Are common mental disorders more prevalent in the UK serving military compared to the general working population?". Psychological Medicine. 45 (9): 1881–1891. doi:10.1017/s0033291714002980. ISSN 0033-2917. PMID 25602942.

- Martin, Pamela Davis; Williamson, Donald A.; Alfonso, Anthony J.; Ryan, Donna H. (February 2006). "Psychological adjustment during Army basic training". Military Medicine. 171 (2): 157–160. doi:10.7205/milmed.171.2.157. ISSN 0026-4075. PMID 16578988.

- Head, M.; Goodwin, L.; Debell, F.; Greenberg, N.; Wessely, S.; Fear, N. T. (1 August 2016). "Post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol misuse: comorbidity in UK military personnel". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 51 (8): 1171–1180. doi:10.1007/s00127-016-1177-8. ISSN 0933-7954. PMC 4977328. PMID 26864534.

- Mattiko, Mark J.; Olmsted, Kristine L. Rae; Brown, Janice M.; Bray, Robert M. (2011). "Alcohol use and negative consequences among active duty military personnel". Addictive Behaviors. 36 (6): 608–614. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.023. PMID 21376475.

- MacManus, Deirdre; Dean, Kimberlie; Jones, Margaret; Rona, Roberto J; Greenberg, Neil; Hull, Lisa; Fahy, Tom; Wessely, Simon; Fear, Nicola T (2013). "Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a data linkage cohort study". The Lancet. 381 (9870): 907–917. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60354-2. PMID 23499041.

- Bouffard, L A (2005). "The Military as a Bridging Environment in Criminal Careers: Differential Outcomes of the Military Experience". Armed Forces & Society. 31 (2): 273–295. doi:10.1177/0095327x0503100206.

- Merrill, Lex L.; Crouch, Julie L.; Thomsen, Cynthia J.; Guimond, Jennifer; Milner, Joel S. (August 2005). "Perpetration of severe intimate partner violence: premilitary and second year of service rates". Military Medicine. 170 (8): 705–709. doi:10.7205/milmed.170.8.705. ISSN 0026-4075. PMID 16173214.

- Child Soldiers International (2017). "Where are child soldiers?". Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Child Soldiers International (2012). "Louder than words: An agenda for action to end state use of child soldiers". Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Child Soldiers International (2016). "A law unto themselves? Confronting the recruitment of children by armed groups". Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- United Nations Secretary-General (2017). "Report of the Secretary-General: Children and armed conflict, 2017". United Nations. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Girl Soldiers – The cost of survival in Northern Uganda, Women News Network – WNN". Womennewsnetwork.net. 13 January 2009. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Michael Leggiere, The Fall of Napoleon: The Allied Invasion of France 1813–1814, pg.99–100

- "Child Soldiers Global Report 2004". Archived from the original on 17 December 2004. (2.29 MB) Child Soldiers International p. 292

- Becker, J (2013). "Campaigning to stop the use of child soldiers". Campaigning for justice: Human rights advocacy in practice. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 11–31. ISBN 9780804774512. OCLC 837635842.

- Child Soldiers International (2017). "International laws and child rights". Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Child Soldiers International (2018). "Child Soldiers World Index". childsoldiersworldindex.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- United Nations Secretary-General (2017). "Report of the Secretary-General: Children and armed conflict, 2017". United Nations. p. 41. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Committee on the Rights of the Child (2016). "General comment No. 20 (2016) on the implementation of the rights of the child during adolescence". tbinternet.ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- UNICEF (2017). "Ending the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "Children, Not Soldiers | United Nations Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict". United Nations. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "Child soldiers from Darfur fighting at front line of war in Yemen, returned soldiers say | The Independent". Archived from the original on 30 December 2018.

- "Saudi Arabia recruited Darfur children to fight in Yemen: NYT | Al Jazeera". Archived from the original on 1 January 2019.

- "On the Front Line of the Saudi War in Yemen: Child Soldiers From Darfur – The New York Times". Archived from the original on 1 January 2019.

- "Colombia's child soldiers". 10 November 2003.

- http://middleeastinst.libsyn.com/child-soldiers-in-the-middle-east?fbclid=IwAR23lG06WtH794cMztuoTzcLTS5PkdOsw5YCJ0mpj-mllInSNdZNqfqBskI

- UNICEF (4 December 2017). "UN Officials congratulate MILF for completion of disengagement of children from its ranks". unicef.org. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- P. W. Singer (14 January 2003). "Facing Saddam's Child Soldiers". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- "AFRICA: Too small to be fighting in anyone's war". UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. December 2003. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- Child Soldiers International (2017). "How many children are used for military purposes worldwide?". Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Singer, Peter (2005). Children at War. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Dallaire, Roméo (2011). They Fight Like Soldiers, They Die Like Children: The Global Quest to Eradicate the Use of Child Soldiers. New York: Walker, and Company.

- Rosenblatt, Roger (1984). "Children of War". American Educator 8. 1: 37–41.

- Child Rights International Network (21 August 2019). "Conscription by poverty? Deprivation and army recruitment in the UK" (PDF). crin.org. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- Child Rights International Network (21 August 2019). "Youngest British army recruits come disproportionately from England's most deprived constituencies" (PDF). Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- Beber, Bernd; Blattman, Christopher (2013). "The Logic of Child Soldiering and Coercion". International Organization. 67 (1): 65–104. doi:10.1017/s0020818312000409. ISSN 0020-8183.

- Child Soldiers International (2016). "Des Milliers de vies à réparer" (in French). Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers (2001). "Global Report on Child Soldiers". child-soldiers.org. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Children Detained in War Zones". 28 July 2016. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- Medact (2018). "House of Commons Defence Committee Inquiry into Armed Forces and Veterans Mental Health: Written Evidence Submitted by Medact". Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- UK, Ministry of Defence (2015). "British Army: Sexual Harassment Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Canada, Statcan [official statistics agency] (2016). "Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces, 2016". statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Marshall, A; Panuzio, J; Taft, C (2005). "Intimate partner violence among military veterans and active duty servicemen". Clinical Psychology Review. 25 (7): 862–876. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.009. PMID 16006025.

- Germany, Bundestag Commission for Children's Concerns (2016). Opinion of the Commission for Children's Concerns on the relationship between the military and young people in Germany.

- Gee, D; Goodman, A. "Army visits London's poorest schools most often" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Gee, D (2008). "Informed Choice? Armed forces recruitment practices in the United Kingdom". Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Hagopian, Amy; Barker, Kathy (1 January 2011). "Should We End Military Recruiting in High Schools as a Matter of Child Protection and Public Health?". American Journal of Public Health. 101 (1): 19–23. doi:10.2105/ajph.2009.183418. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3000735. PMID 21088269.

- American Public Health Association (2012). "Cessation of Military Recruiting in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools". apha.org. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Soldiers of Misfortune: Abusive U.S. Military Recruitment and Failure to Protect Child Soldiers". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Strasburger, V C (2013). Children, adolescents, and the media (Chapter 1). Wilson, Barbara J., Jordan, Amy B. (Amy Beth) (Third ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. ISBN 9781412999267. OCLC 820450764.

- Louise, R; et al. (17 November 2016). "The recruitment of children by the UK armed forces: A critique from health professionals". Medact. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Spear, L. P. (June 2000). "The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 24 (4): 417–463. doi:10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 10817843.

- UNICEF (2007). "Paris Principles: Principles and guidelines on children associated with armed forces or armed groups" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- International Committee of the Red Cross (1977). "Protocols additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (A/CONF.183/9)" (PDF). 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- International Labour Organization. "Ratifications of C182 – Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182)". ilo.org. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Geneva Call (2012). "Engaging nonstate armed groups on the protection of children: Towards strategic complementarity" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (2018). "African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child". achpr.org. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ICRC Commentary on Protocol I: Article 77 Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine website of the ICRC ¶ 3183–3191 also ¶ 3171 Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Protocol II Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949". ohchr.org. 1977. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "UNICEF: Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child". UNICEF. 30 November 2005. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014. Yun, Seira (2014). "Breaking Imaginary Barriers: Obligations of Armed Non-State Actors Under General Human Rights Law – The Case of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child". Journal of International Humanitarian Legal Studies. 5 (1–2): 213–257. doi:10.1163/18781527-00501008. SSRN 2556825.

- John-Peter., Pham (2005). Child soldiers, adult interests : the global dimensions of the Sierra Leonean tragedy. New York: Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 9781594546716. OCLC 61724289.

- Lauren McCollough, The Military Trial of Omar Khadr: Child Soldiers and the Law Archived 12 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Crimes of War Project Archived 22 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine 10 March 2008

- The Paris Principles and Guidelines on Children associated with armed forces or armed groups Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, February 2007. Section "Treatment of children accused of crimes under international law", p. 9

- Jane Sutton (9 August 2010). "Omar Khadr's Confession Can Be Used at Guantanamo Trial". Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "USvKhadr Stipulation of Fact" (PDF). 25 October 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Meserve, Jeanne; CNN Wire Staff (25 October 2010). "Youngest Guantanamo detainee pleads guilty". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2010.